Abstract

Materials combining the hardness and strength of diamond with the higher thermal stability of cubic boron nitride (cBN) have broad potential value in science and engineering. Reacting nanodiamond with cBN at moderate pressures and high temperatures provides a pathway to such materials. Here we report the fabrication of Cx-BN nanocomposites, measuring up to 10 mm in longest dimension, by reacting nanodiamond with pre-synthesized cBN in a large-volume press. The nanocomposites consist of randomly-oriented diamond and cBN domains stitched together by sp3-hybridized C-B and C-N bonds, leading to p-type semiconductivity. Dislocations near the sutures accommodate lattice mismatch between diamond and cBN. Nanotwinning within both diamond and cBN domains further contributes to a bulk hardness ~50% higher than sintered cBN. The nanocomposite of C2-BN exhibits p-type semiconductivity with low activation energy and high thermal stability, making it a functional, ultrahard substance.

Superhard and ultrahard materials, presently defined as having Vickers hardness (HV) greater than 40 and 80 GPa, respectively, are sought after for their potential use as extreme abrasives and other applications in high-pressure science and technology1,2,3,4. Diamond is generally considered the hardest known substance, but due to graphitization in air at 800–900 K and reactivity with transition metals at high temperature, diamond has limited application in certain grinding environments. Cubic boron nitride (cBN), a diamond-structured compound, is widely used as an abrasive with much higher thermal stability than diamond (~1473 K) and low reactivity with steel, but the Vickers hardness of cBN (40–60 GPa)5,6 is only about half that of diamond. Because of their similar ionic radii, B, C, and N may form diamond-like compounds in solid solution that are expected to be ultrahard with higher thermal and chemical stability than diamond7,8,9,10,11,12. Based on theoretical predictions, experimental studies have attempted to synthesize a number of superhard B-C-N materials including diamond-like BC2N13, BC4N10, BC3 14 and BC5 15,16. However, solid-solution B-C-N phases are generally considered metastable because syntheses usually lead to segregated carbon and boron compounds17. The extremely high pressures (20–25 GPa) and temperatures (2000–2500 K) of many B-C-N syntheses ultimately limit production potentials and sample size7,15,17.

Recently, it was discovered that nanotwinned (nt) diamond3 and nt-cBN2,18 possess ultrahigh hardness and toughness, mitigating the so-called reverse Hall-Petch effect by shear strengthening from compressive forces across nanospaced twin boundaries18. Combining nt-diamond and nt-cBN to create an ultrahard nanocomposite would potentially lead to a material with optimized properties of each. Reacting diamond and cBN at high pressure and high temperature (HPHT) has been the typical route to synthesizing composites of diamond and cubic boron nitride (Cx-BN)19,20,21,22,23, where x is the proportion of diamond relative to cBN. The conditions and mechanisms of stitching diamond and cBN together remains the primary challenge. Recently, an epitaxial cBN/diamond heterojunction was produced by growing single-crystal cBN on diamond seed crystals using a temperature gradient method24. A network of continuous stacking faults, arranged by hexagonal dislocation loops on the {111} heterointerface was found to accommodate the cBN/diamond lattice mismatch (~1.4 Å)24. In this study, we fabricated highly uniform Cx-BN (x = 2, 4, 6, 8) nanocomposites at 7.5 GPa and 2273 K, which consist of randomly oriented, ~50 nm domains of diamond and cBN (~250 nm). The bulk samples, measuring up to 10-mm diameter by 5-mm in height, combine several novel features from recent syntheses in the diamond-cBN system2,3,18,24; in particular, the new C2-BN composite possesses nanotwinning in both diamond and cBN domains, which are stitched by sp3-hybridized C-B and C-N bonds along randomly-oriented interfaces. Near the sutures, dislocations accommodate the lattice mismatch between diamond and cBN and, as recently predicted24, the C2-BN nanocomposite is a p-type semiconductor with low activation energy. Among the suite of new nanocomposites, C2-BN is the hardest, with Hv = 85(2) GPa, placing it in the ultrahard class of materials.

We control the stoichiometry in Cx-BN, by varying the proportions of starting powders of diamond (average grain size 50 nm) and cBN (average grain size 250 nm). Synthesis was conducted at 7.5 GPa while holding constant temperature of 2273 K for two hours (Table 1). The components of C2-BN remain diamond-structured; however, the recovered Cx-BN composites with C4-BN, C6-BN, and C8-BN contained diamond and cBN together with appearance of graphitic phase (Fig. S1). The presence of minor amounts of graphite decreases with increasing ratio of cBN added to the starting material, indicating that cBN plays a role as catalyst in stitching diamond and cBN domains while protecting the diamond from graphitization at the high temperatures of synthesis (2273 K). Since the aim of this study is to synthesize and characterize nanopolycrystalline Cx-BN composite free of graphite, here we focus on the physical properties of C2-BN, which was the only sample not exhibiting the presence of graphite.

Table 1. Synthesis conditions and electrical properties of nanopolycrystalline C x -BN composites.

| Run | Sample | P (GPa) | T (K) | p/n | Resistivity (Ωcm) | Hall mobility (cm2/VS) | Carrier concentration (cm−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-1 | Sintered-BN | 7.5 | 2273 | / | / | / | / |

| S-2 | C2-BN | 7.5 | 2273 | p | 1.652 | 37.55 | 1.006E17 |

| S-3 | C4-BN | 7.5 | 2273 | p | 0.162 | 2.67 | 1.439E19 |

| S-4 | C6-BN | 7.5 | 2273 | p | 0.571 | 364.69 | 2.999E16 |

| S-5 | C8-BN | 7.5 | 2273 | n | 0.055 | 46.62 | 2.426E18 |

| S-6 | Sintered-C | 7.5 | 2273 | n | 0.014 | 15.68 | 2.749E19 |

| S-7 | Single-crystal diamond | 5-5.5 | 1500 | / | / | / | / |

| S-8 | Single-crystal cBN | 4.8 | 1400 | / | / | / | / |

| Microcrystalline samples | |||||||

| S-9 | C2-BN (microcrystalline) | 7.5 | 2273 | p | 6.38 | 6.55 | 1.490 E16 |

| S-10 | C2-BN (microcrystalline) | 7.5 | 1800 | p | 1064 | 162 | 3.624 E14 |

Temperature was held constant for two hours. The Cx-BN composites consist of sintered nanodiamond (50 nm) and cBN (250 nm) with varying ratios (x) of diamond to cBN. For comparison, microcrystalline C2-BN composites from two different synthesis temperatures demonstrate the decrease in resistivity with increasing temperature between 1800 and 2273 K.

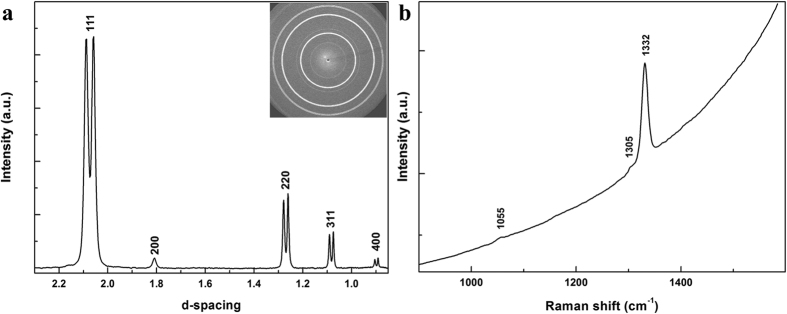

Figure 1a shows a representative X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the recovered C2-BN composite. With increasing synthesis temperature, the diffraction lines become broader and the peaks of diamond and cBN from the 2273 K synthesis have considerable overlap (Fig. S1). Raman spectra (Fig. 1b) of C2-BN produced at 7.5 GPa and 2273 K are dominated by one sharp Raman peak at 1332 cm−1 and two weak peaks at about 1055 and 1305 cm−1, corresponding to diamond and cBN longitudinal optical and transverse optical modes, respectively. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum (Fig. S2) shows two main peaks at 1065 and 1318 cm−1 together with one weak shoulder at 1208 cm−1, which correspond to stretching of the sp3 B-N bonds in cBN21,22, C-N bonds within the sutures of diamond and cBN domains25 and C-C bonds in diamond26, respectively. This characterization shows that the C2-BN samples consist of diamond and cBN domains, consistent with XRD data (Fig. 1a). The recovered samples from 7.5 GPa and 1500–2273 K were black and opaque, while transparent samples were achieved by subsequent annealing at 15–18 GPa and 2100 K (Fig. S3).

Figure 1. Characterization of C2-BN synthesized at 7.5 GPa and 2273 K.

(a) XRD and (b) Raman spectra indicate two components, diamond and cBN. Rings in the CCD image (top-right inset in 1a) show the polycrystalline texture of well-sintered C2-BN composite.

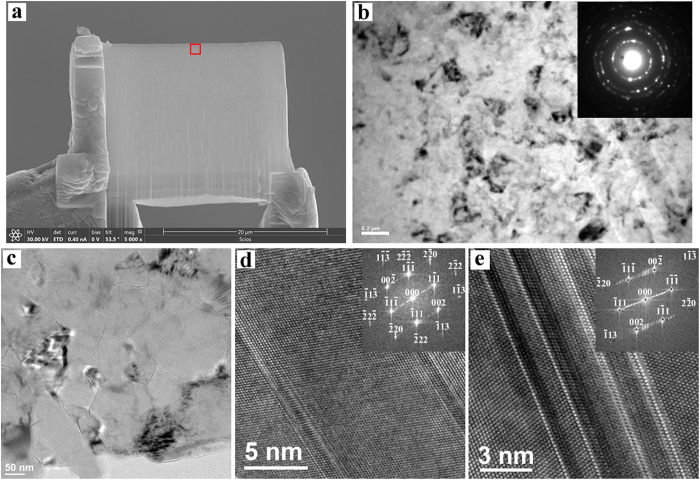

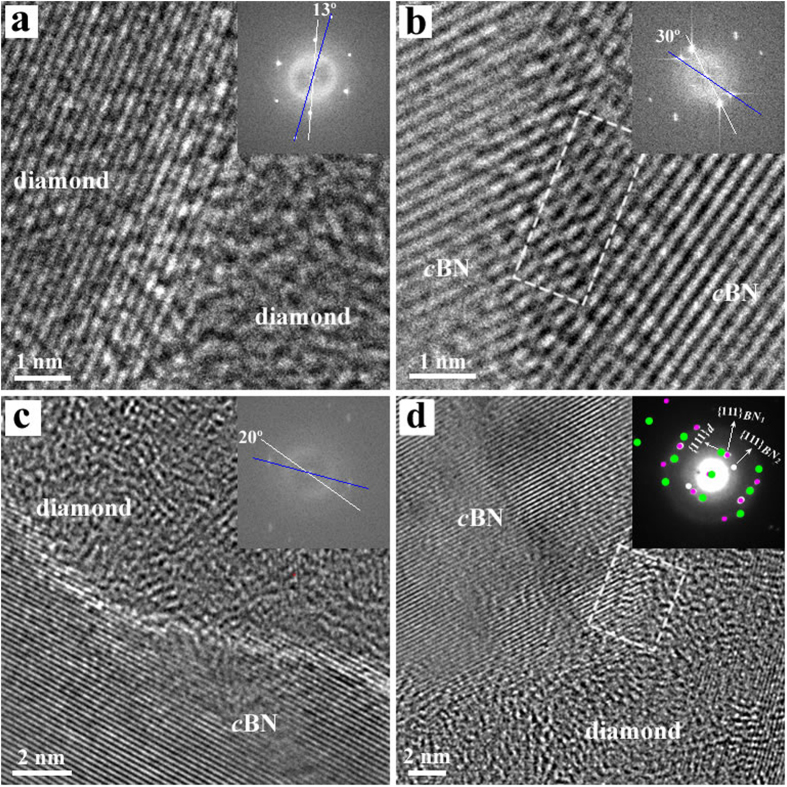

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) confirms the C2-BN composite is uniform and well sintered (Fig. 2a). Thin foils of C2-BN synthesized at 7.5 GPa and 2273 K were prepared by focused-ion beam (FIB) techniques for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Characteristic TEM and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images are shown in Fig. 2b–e. The TEM images in Fig. 2b,c show the absence of porosity in the C2-BN sample, unlike many sintered diamond samples from which catalysts have been removed. The samples exhibit a nanopolycrystalline structure, consisting of hybridized, randomly distributed diamond and cBN domains (Figs S4 and S5). Furthermore, HRTEM images reveal that nanotwinned structures have been produced during HPHT treatment (Fig. 2d,e). These multiple twins in the diamond and cBN domains are 1.5–2 nm and 6–8 nm wide, respectively. HRTEM images in Fig. 3 show that the two main domains of diamond and cBN have been stitched together by high-pressure sintering. The rigid lattice misfit between diamond and cBN domains is accommodated by the presence of partial dislocations and stacking faults at the interface between the two domains (Fig. S6)24. The sutures between diamond-cBN domains are typically 1–2 nm thick. HRTEM images and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns (Fig. 3c,d) from the diamond-cBN junctions reveal that cBN domains twin to conjoin the adjacent diamond. Stacking faults and dislocations are observed in cBN in close proximity to the interfaces (Fig. S6). Through this misfit accommodation mechanism24, strain between diamond and cBN domains is released, leading to stability of the C2-BN composite.

Figure 2. Microstructure of nanocomposite C2-BN.

(a) TEM lamellae obtained from a C2-BN bulk sample before focused ion-beam (FIB) thinning. (b,c) TEM images of the area with the red box in (a). The inset of (b) shows a selected area diffraction (SAED) pattern (d and e) HRTEM images of the nanotwinned diamond and cBN domains. Insets show calculated FFT patterns of the two main domains.

Figure 3. Ultrahard sutures in nanocomposite C2-BN.

(a–c) HRTEM images at the junction between diamond and cBN domains. The FFT inset shows the rotation angles between adjacent diamond or cBN domains. (d) HRTEM and corresponding SAED pattern from a typical junction indicates that only nano-twinned diamond and cBN are present at the interface. Dislocations and stacking faults at the interface are found in the region marked by the white rectangle in (b) and (d).

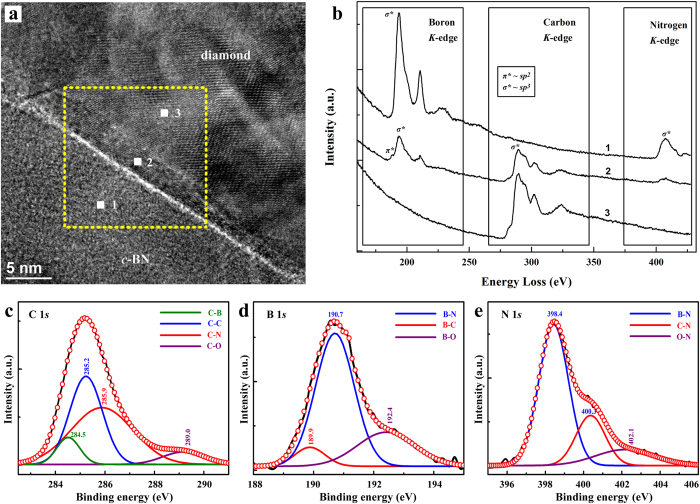

To determine the local bonding characteristics across the diamond-cBN sutures, we carried out inelastic X-ray scattering (IXS; beam size 20 μm) and electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS; beam size 1 nm) on the C2-BN sample. The IXS spectra in Fig. S7 show that all three elements, B, C and N, are sp3 hybridized along the sutures. In contrast, pure diamond sintered under identical conditions (7.5 GPa and 2273 K) exhibits both sp2 and sp3 bonds (Fig. S8). This confirms that graphitization of sintered diamond can be effectively minimized or eliminated in C2-BN by choosing the optimal synthesis conditions. EELS was conducted to analyze the interface between diamond and cBN from the selected area in the C2-BN sample from 2273 K (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b shows the EELS spectrum and all the three bonds corresponding to the characteristic K-shell ionization edges of B, C and N in the diamond-cBN interface. These EELS edge structures prove that bonding within the sutures are primarily sp3-hybridized B-C-N bonds together with small amount of sp2 C-B bonds.

Figure 4. Evidence for sp3-hybridized C-B and C-N in nanocomposite C2-BN.

(a) HRTEM image of C2-BN (b) EELS taken from C2-BN along the suture between diamond and cBN domains. EELS data were collected with a beam approximately 1 × 1 nm in size. Symbols π* and σ* correspond to sp2 and sp3 bonding, respectively. (c–e) XPS spectra of B, C, and N 1s core levels, respectively. The spectra (red circles) are deconvolved (colored curves) by Gaussian fitting.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed to study the stoichiometry of the hybridized diamond-cBN junctions. Figures 4c–e show XPS spectra of B, N and C, respectively. The shape and position of the spectra for all three elements are different from previous studies on pure diamond27, cBN28, and B-C-N compounds29,30. The C 1s peak is located at 285.2 eV (Fig. 4c), which is similar to the value of C 1s in sp3 C-C bonds observed in diamond31. The full width at half-maximum (FWHM) is about 2.3 eV, suggesting different valence states of carbon are present. Two smaller peaks at higher (285.9 eV) and lower (284.5 eV) binding energy are due to C 1s in sp3 C-N and C-B bonds, respectively32. In addition, a higher binding energy at 289.0 eV is observed from the contribution of C 1s in C-O bonds29,33. The main peak of the B 1s spectrum is located at 190.7 eV, very close to that of B 1s (191.0 eV) in pure cBN28,29, suggesting the main bonding configuration in the C2-BN composite produced at 7.5 GPa and 2273 K is similar to that of cBN, where one N atom is surrounded by four B atoms. However, a small shoulder at lower binding energy implies a contribution of B and C, because of the lower electronegativity of C atoms than N34. A higher binding energy at 192.4 eV implies a contribution from the configuration of B 1s in B-O bonds35. The N 1s binding energy is located at 398.4 eV (Fig. 4e), similar to the position of N 1s in cBN28,29. However, two small shoulders are observed at higher binding energy of 400.3 and 402.1 eV, which are due to N 1s in C-N and C-O, respectively29,30. All the C 1s, B 1s and N 1s spectra indicate that the main configuration for C, B and N atoms is sp3 B-N bonding, together with a contribution from the bonding configuration in the boundary region between diamond and cBN domains. In addition to sp3-hybridized C-N and C-B bonds produced during HPHT reaction, some C-O, B-O, and N-O bonds remain from the starting materials exposed to air.

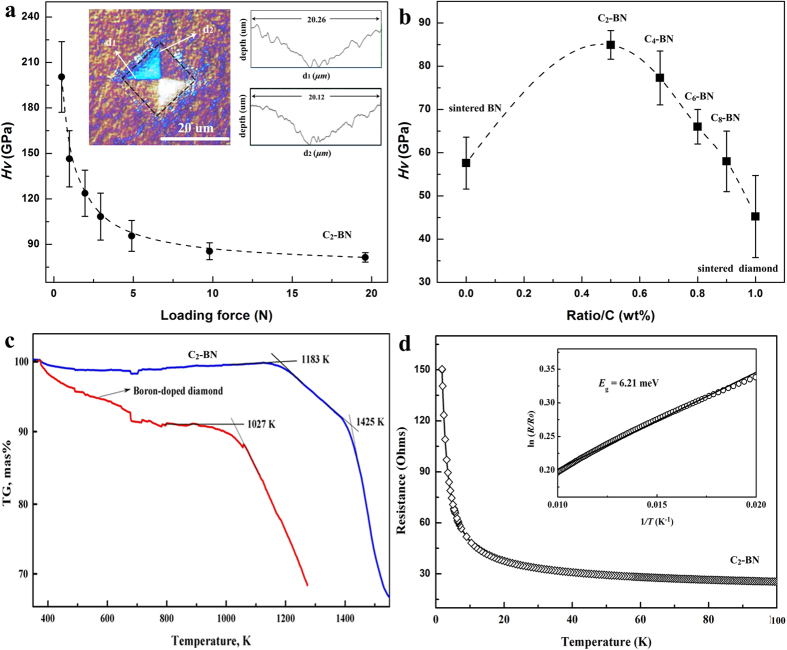

Vickers hardness measurements were conducted on the Cx-BN nanocomposites using a standard square-pyramidal diamond indenter. We imaged and compared the indented surfaces using an optical microscope, SEM, and well-calibrated 3D optical microscope to determine the HV value. Figure 5a shows the hardness-load curve of C2-BN. The asymptotic region is reached at loads above 4.9 N and shows an ultrahard value of 82(3) GPa at 19.6 N. In a second C2-BN sample, the indentation at 19.6 N load corresponded to HV = 85(2) GPa, confirming the ultrahard value of our nanocomposite C2-BN. For other compositions of Cx-BN as well as cBN and sintered diamond, we studied indentations at 19.6 N load and found a peak hardness for the composition C2-BN (Fig. 5b). HV of the sintered diamond sample is lower than sintered cBN because of the presence of a graphitic phase on the diamond surface (Fig. S8).

Figure 5. Mechanical and electrical properties of C2-BN nanocomposite.

(a) Hv of C2-BN as a function of applied load. Left inset: Optical micrograph of an indentation in C2-BN produced by a load of 19.6 N. Right inset images in (a) show profiles across d1 and d2 measured using a 3D microscope. (b) Hv as a function of composition for Cx-BN materials. For comparison, we measured the Vickers hardness of Cx-BN with higher diamond:cBN ratios at only the highest load of 19.6 N. The measured indentation hardness of Cx-BN ranged from 40 GPa to 85 GPa. (c), Thermogravimetric data (in air) for C2-BN (the onset temperature of oxidation Tox is 1183 K) and boron-doped diamond single crystals (Tox~1027 K). (d) A resistance-versus-temperature curve for C2-BN measuring 2 × 2 mm and 1 mm thick. The inset in (d) shows ln (R) as a function of T−1 in the temperature range from 50 to 100 K. The linear fit (solid line) shows that the data are well described by R(T) ∝ exp(Eg/kBT), where Eg is the activation energy and kB is Boltzmann’s constant.

The compressibility of C2-BN was studied under quasi-hydrostatic pressures up to 40 GPa at 300 K in a diamond-anvil cell using synchrotron X-ray diffraction at Sector 16 (HPCAT) of the Advanced Photon Source (APS). Figure S10 shows the compression data of diamond and cBN domains in the bulk C2-BN sample, together with the previously reported equations of state of single-crystal diamond36 and ultrahard nanopolycrystalline (NP) cBN17. The P-V data (Table S2) were fitted to a third-order Vinet equation of state, finding for diamond V0 = 45.33 (±0.01) Å3 and KT0 = 436.4 (±2.3) GPa when K0’ = 3.0 is fixed to the value from a previous study36 to allow for better comparison of KT0. Our value of KT0 is close to the adiabatic bulk modulus derived from recent ultrasonic measurements, KT0 = 441.8 (±0.8) for single-crystal diamond and KT0 = 442.5 (±0.5) GPa for NP-diamond37. For the cBN domains, we obtained V0 = 47.30 (±0.01) Å3 and KT0 = 398.6 (±2.5) GPa when K0’ = 2.3 is fixed to the value of a previous study17,38. When K0’ is allowed to refine, we obtain V0 = 47.33 (±0.01) Å3, KT0 = 377.4 (±7.1) GPa, and K0’ = 3.6 (±0.4) (Fig. S10). Using KT0 = 398.6 (±2.5) GPa for the cBN domains, we obtain a theoretical nanopolycrystalline average KT0 value of the C2-BN composite of 417.5 (±2.4) GPa.

We also determined the thermal stability (in air) of the Cx-BN samples by thermoanalytical analysis (TG/DTG) from 400 K to 1620 K (Fig. 5c). The synthetic C2-BN sample shows remarkably higher stability than either single-crystal boron-doped diamond (~1000 ppm) with the onset temperature of oxidation in air, TOX ~1027 K, or nanopolycrystalline diamond (TOX ~950 K)17. The synthetic nanocomposite of C2-BN remains stable up to 1183 K. Moreover, the oxidation rate for C2-BN composite decreases substantially between 1183 K and 1425 K.

To investigate the electrical properties of our synthetic Cx-BN nanocomposites, Hall measurements were performed with four electrodes at room temperatures (Table 1). The sintered diamond (sample S6) and Cx-BN materials with high carbon concentration (sample S5) show good n-type conductivity with a low resistivity that can be due to the graphitization under HPHT treatment. Both C2-BN and C4-BN nanocomposites synthesized at 2273 K and 7.5 GPa exhibit p-type semiconductivity. Resistivity of the p-type Cx-BN is observed to decrease and the carrier concentration increases with increasing synthetic temperature condition up to 2273 K (sample S9 and S10). The p-type Cx-BN synthesized at 2273 K (sample S2-4) shows low electrical resistivity, and the electron and hole mobility is in a wide range of 2.7–365 cm2 V−1 s−1. The carrier concentration of the C2-BN composite can reach 1.4387 × 1019 cm−3 at 300 K. This value is comparable with that of B-doped diamond39. These results suggest that we can control the electrical properties of our Cx-BN materials from insulator to highly conducting by adjusting synthetic P-T or tuning the ratio between the C and BN with high flexibility and applications in electronics.

Temperature-dependent electrical measurements on our C2-BN nanocomposite (Fig. 5d) show a significant increase in resistance by more than 7-fold on cooling from room temperature (ρ = 21Ω) to 1.8 K, a typical semiconducting behavior. The value of the activation energy is calculated on the basis of a linear Arrhenius plot of the logarithm of the resistance ln (R) versus the inverse temperature T−1 in the temperature range between from 100 K and 50 K (See Fig. 5d, inset). The calculated activation energy is 6.21 meV and is similar to hybridized BN-C graphene30. Since both pure diamond and cBN are good insulators, the p-type semiconductivity of the Cx-BN composite must derive from the sp3-hybridized C-B and some B-B bonds within the sutures of diamond and cBN domains30,40.

This study introduces a new strategy and direction in the search for novel conductive ultrahard materials. Nanocomposite Cx-BN materials will enable the design of particular physical properties in diamond-based structures. Previously, B-doping has been the most effective method used to control the electrical properties of diamond. However, it is difficult to synthesize high-quality diamond crystals with heavy B-doping because boron is typically heterogeneously distributed within the crystal and it is difficult to avoid graphitic defects41,42. The current synthesis and characterization of p-type bulk nanopolycrystalline Cx-BN with low activation energy suggests that stable and uniform diamond-based semiconductors can be formed in large quantities and in a reproducible way. In addition, the well-sintered nanopolycrystalline bulk pieces possess no cleavage, which will allow Cx-BN composite materials to be fabricated into arbitrary shapes for industrial applications such as machine parts. Combining the high thermal conductivity and radiation resistance of diamond with the toughness of cBN at high temperatures, the ultrahard Cx-BN bulk nanocomposites have potential applications in electronics under extreme thermal and pressure conditions.

In summary, we synthesized Cx-BN composites with dimensions up to 10 mm × 5 mm at 7.5 GPa and 2273 K. The composite of nanotwinned diamond and cBN in a 2:1 ratio (C2-BN) shows ultrahard properties by Vickers indentation tests, low compressibility, high thermal stability, and p-type semiconductivity - a combination of features that have not previously been found together in pure diamond-like B-C-N materials. Subsequent annealing at 15–18 GPa and 2100 K improves its transparency. The nanotwinned domains of diamond and cBN are stitched by sp3-hybridized C-B and C-N bonds with dislocations near the grain boundaries to accommodate the rigid lattice mismatch of diamond and cBN, thus combining the features of a variety of recently reported ultrahard materials1,2,3,18,23,24. The moderate synthesis P-T conditions and rapid annealing time (2 hours) to form ultrahard nanopolycrystalline C2BN composite make it a promising material for machine tooling with other practical benefits. The unique combination of properties in C2-BN provides a pathway for fabrication of diamond-based electronics applicable to multifunctional devices operating in extreme environments.

Methods

Sample synthesis and characterization

HP-HT synthesis experiments were carried out using a China-type cubic high-pressure apparatus (SPD-6×1200) at the State Key Laboratory of Superhard Materials, Jilin University. High-purity mixtures were prepared of nanodiamond (50 nm) and cBN (250 nm) with varying ratios (x) of diamond to cBN (i.e. Cx-BN), including BN, C2-BN, C4-BN, C6-BN, C8-BN, C10-BN, C12-BN and C. The starting materials were prepared by mechanically mixing for five hours at ambient conditions and treated by hot sulfuric acid/diluted hydrochloric acid to remove impurities introduced during the milling progress. Synthesis temperatures were measured using a Pt-30% Rh/Pt-6%Rh thermocouple junction placed within 0.5 mm of the sample. Pressure was pre-calibrated at high temperatures by the graphite-diamond transition with different catalysts. Samples were first subjected to pressures of 7.5 GPa, heated to temperatures of 1500–2273 K with holding times of 2 hours before rapidly cooling to room temperature in 2 minutes. The Cx-BN cylinders (10-mm diameter × 5-mm height) are black in color. One sample of C2-BN was re-annealed at 15–18 GPa and 2100 K for 2 hours using the 1000-ton multi-anvil press at GSECARS (Sector 13) of the APS, Argonne National Laboratory (ANL), producing a transparent and colorless run product (Fig. S3). Run products were initially studied using an optical microscope, SEM, a powder XRD diffractometer, and Raman spectroscopy. Then we employed HRTEM, EELS, IXS, and XPS measurements on the produced Cx-BN composites to determine their chemical compositions and crystal structures.

Hardness and thermal stability measurement

Vickers Hardness measurements were performed in the Optical Microscopy & Metallography (OMM) Facility at Northwestern University. A microhardness tester (KB 5 BVZ) was used to measure HV with a diamond Vickers indenter. HV was determined from HV = 1,854.4F/d2, where F (in Newtons) is the applied load and d (in μm) is the arithmetic mean of the two diagonals (d1 and d2) of the Vickers indentation (Fig. 5a). For C2-BN, the average of at least seven hardness data points for each load value was used to determine the HV from the asymptotic intercept. To study the effect of cracking around the projected area on the inferred indentation dimensions, we used a combination of optical microscopy, SEM, and a high-resolution 3D microscope (Bruker, ContourGT Optical Profiler) to analyze the indented surface. The dynamic TG/DTG studies were performed in air using the NETZSCH STA 449 C thermoanalyser operating at a heating rate of 10 K min−1 in the temperature range from 200 to 1650 K. These bulk samples were crushed into powders of micron sizes before the thermoanalytical studies.

Compressibility

The compressibility measurement was carried out in diamond-anvil cell using neon as the pressure medium. High-pressure X-ray diffraction patterns were collected up to 40 GPa, with exposure times of 5–10 min, at room temperature at beamline 16BM-D (HPCAT) of the APS. The beam size was ~5 × 10 μm at FWHM. Pressure was measured using the ruby fluorescence method43. A fragment of C2-BN (50 μm diameter, 8–10 μm thick) was placed into the 160-μm diameter hole of a rhenium gasket, pre-indented to 25 μm thickness.

Electrical measurement

The van der Pauw method was used for electrical transport measurements, in which four electrodes were used in the resistivity measurements. The electrical characteristics were measured with a transport properties measuring system (East Changing ET 9000 Series). The resistivity measurements were carried out at room temperature (300 K) and normal humidity level (40% RH). The temperature dependence of the resistance was measured using a standard four-probe method (PPMS, Quantum Design).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, X. et al. Ultrahard stitching of nanotwinned diamond and cubic boron nitride in C2-BN composite. Sci. Rep. 6, 30518; doi: 10.1038/srep30518 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF grants DMR-1508577 to SDJ and CRB, EAR-1361276 to YW, and DMR-1411344 to JG. SDJ also acknowledges support from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, and the Carnegie/DOE Alliance Center (CDAC). Synthesis experiments were performed at State Key Lab of Superhard Materials, Jilin University. Sample characterization was conducted in the EPIC facility (NUANCE Center-Northwestern University), supported by the MRSEC program (NSF DMR-1121262) at the Materials Research Center, the International Institute for Nanotechnology (IIN), and the State of Illinois. Annealing experiments carried out at GESCARS (Sector 13 of the APS) were supported by the NSF (EAR-1128799) and DOE (DE-FG02-94ER14466). The FIB at Bayerisches Geoinstitut, University of Bayreuth, Germany, was financed by DFG grant No. INST 91/315-1 FUGG. The Optical Microscopy & Metallography Facility at Northwestern University receives support from the MRSEC Program (NSF DMR-1121262) of the Materials Research Center. Portions of this work were performed at HPCAT (Sector 16 of the APS). HPCAT operations are supported by DOE-NNSA under Award No. DE-NA0001974 and DOE-BES under Award No. DE-FG02-99ER45775, with partial instrumentation funding by NSF. We thank Changyong Park for assistance with the XRD measurements at HPCAT. Use of the APS was supported by the DOE-BES under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

Author Contributions X.L. designed the study. X.L., X.C., S.D.J., Y.W. and C.R.B. wrote the manuscript. X.L., X.C., H.-A.M. and X.J. synthesized the samples and performed the thermoanalytical measurements. J.G. performed the electrical measurements. X.L., T.Y. and Y.W. conducted HPHT annealing experiments. X.L. performed the high-pressure X-ray diffraction experiments. S.D.J. and S.P. conducted FIB preparation, X.L. and J.W. conducted SEM and HRTEM measurements. All authors contributed to data analysis, interpretation, and revision of the manuscript.

References

- Irifune T., Kurio A., Sakamoto S., Inoue T. & Sumiya H. Materials: Ultrahard polycrystalline diamond from graphite. Nature 421, 599–600 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y. et al. Ultrahard nanotwinned cubic boron nitride. Nature 493, 385–388 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q. et al. Nanotwinned diamond with unprecedented hardness and stability. Nature 510, 250–253 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou H. et al. Discovery of a superhard iron tetraboride superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 157002 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentorf R., DeVries R. C. & Bundy F. Sintered superhard materials. Science 208, 873–880 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X., Liew W. & Liu X. Evaluation of machining performance of MMC with PCBN and PCD tools. Wear 259, 1225–1234 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Knittle E., Kaner R., Jeanloz R. & Cohen M. High-pressure synthesis, characterization, and equation of state of cubic C-BN solid solutions. Phys. Rev. B 51, 12149 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger J. et al. Discovery of hardest known oxide. Nature 383, 401–401 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Liu A. Y. & Cohen M. L. Prediction of new low compressibility solids. Science 245, 841–842 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. et al. Superhard B-C-N materials synthesized in nanostructured bulks. J. Mater. Res. 17, 3139–3145 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Kaner R. B., Gilman J. J. & Tolbert S. H. Designing superhard materials. Science 308, 1268–1269 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeds J. et al. Use of novel methods for the investigation of the boron distribution in CVD diamond. Acta Mater. 47, 4025–4030 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Solozhenko V. L., Andrault D., Fiquet G., Mezouar M. & Rubie D. C. Synthesis of superhard cubic BC2N. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. et al. Superhard BC3 in cubic diamond structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 015502 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solozhenko V. L., Kurakevych O. O., Andrault D., Le Godec Y. & Mezouar M. Ultimate metastable solubility of boron in diamond: synthesis of superhard diamondlike BC5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 015506 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. et al. Superhard and superconducting structures of BC5. J. Appl. Phys. 108 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Solozhenko V. L., Kurakevych O. O. & Le Godec Y. Creation of nanostuctures by extreme conditions: high-pressure synthesis of ultrahard nanocrystalline cubic boron nitride. Adv. Mater. 24, 1540–1544 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Sun H. & Chen C. Large indentation strain-stiffening in nanotwinned cubic boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 5 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima O., Tanaka J., Yamaoka S. & Fukunaga O. High-temperature cubic boron nitride pn junction diode made at high pressure. Science 238, 181–183 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi T. & Yamaoka S. In MRS Proceedings. 379 (Cambridge Univ Press). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. et al. Epitaxy on diamond by chemical vapor deposition: a route to high-quality cubic boron nitride for electronic applications. Adv. Mater. 16, 1405–1408 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. et al. Epitaxy of cubic boron nitride on (001)-oriented diamond. Nat. Mater. 2, 312–315 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. et al. Diamond-cBN alloy: A universal cutting material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 101901 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. et al. Misfit accommodation mechanism at the heterointerface between diamond and cubic boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Huang J., Zhou H. & Antonietti M. Uniform graphitic carbon nitride nanorod for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and sustained photoenzymatic catalysis. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 6, 8434–8440 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M. H., Byrne J. A., McLaughlin J., Elhissi A. & Ahmed W. Comparison between FTIR and XPS characterization of amino acid glycine adsorption onto diamond-like carbon (DLC) and silicon doped DLC. Appl. Surf. Sci. 273, 507–514 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Belton D. N., Harris S. J., Schmieg S. J., Weiner A. M. & Perry T. A. Insitu characterization of diamond nucleation and growth. Appl. Phys. Lett. 54, 416–417 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Hao X. et al. Synthesis of cubic boron nitride at low-temperature and low-pressure conditions. Chem. Mater. 13, 2457–2459 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. et al. Synthesis and characterization of new “BCN” diamond under high pressure and high temperature conditions. Cryst. Growth Des. 11, 1006–1014 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ci L. et al. Atomic layers of hybridized boron nitride and graphene domains. Nat. Mater. 9, 430–435 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merel P., Tabbal M., Chaker M., Moisa S. & Margot J. Direct evaluation of the sp3 content in diamond-like-carbon films by XPS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 136, 105–110 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G. et al. Sulfonated graphene for persistent aromatic pollutant management. Adv. Mater. 23, 3959–3963 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazare S., Hoh P. D., Baker J. M. & Srinivasan R. Controlled modification of organic polymer surfaces by continuous wave far-ultraviolet (185 nm) and pulsed laser (193 nm) radiation: XPS studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 4288–4290 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Paul R., Voevodin A. A., Zemlyanov D., Roy A. K. & Fisher T. S. Microwave-assisted surface synthesis of a boron-carbon-nitrogen foam and its desorption enthalpy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 3682–3690 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Yin L. C., Niu P., Jiao W. & Cheng H. M. Visible-light-responsive β-rhombohedral boron photocatalysts. Angew. Chem. 125, 6362–6365 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occelli F., Loubeyre P. & LeToullec R. Properties of diamond under hydrostatic pressures up to 140 GPa. Nat. Mater. 2, 151–154 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.-Y., Jacobsen S. D., Kimura M., Irifune T. & Ohno I. Elastic properties of transparent nano-polycrystalline diamond measured by GHz-ultrasonic interferometry and resonant sphere methods. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 228, 47–55 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Datchi F., Dewaele A., Le Godec Y. & Loubeyre P. Equation of state of cubic boron nitride at high pressures and temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 75, 214104 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Lee S. T. & Lam Y. Characterization of heavily boron-doped diamond films. Diamond Relat. Mater. 5, 1288–1294 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M., Itoh S., Sasaki T. & Mizushima K. Visible-light-emitting layered BC2N semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 187 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurzinger P., Pongratz P., Hartmann P., Haubner R. & Lux B. Investigation of the boron incorporation in polycrystalline CVD diamond films by TEM, EELS and Raman spectroscopy. Diamond Relat. Mater. 6, 763–768 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Dubrovinskaia N. et al. Superhard nanocomposite of dense polymorphs of boron nitride: Noncarbon material has reached diamond hardness. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 101912 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Mao H., Xu J.-A. & Bell P. Calibration of the ruby pressure gauge to 800 kbar under quasi-hydrostatic conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Sol. Ea. 91, 4673–4676 (1986). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.