Abstract

Rapid and widespread growth in the use of nuclear medicine for both diagnosis and therapy of disease has been the driving force behind burgeoning research interests in the design of novel radiopharmaceuticals. Until recently, the majority of clinical and basic science research has focused on the development of 11C-, 13N-, 15O-, and 18F-radiopharmaceuticals for use with positron emission tomography (PET) and 99mTc-labeled agents for use with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). With the increased availability of small, low-energy cyclotrons and improvements in both cyclotron targetry and purification chemistries, the use of “nonstandard” radionuclides is becoming more prevalent. This brief review describes the physical characteristics of 60 radionuclides, including β+, β−, γ-ray, and α-particle emitters, which have the potential for use in the design and synthesis of the next generation of diagnostic and/or radiotherapeutic drugs. As the decay processes of many of the radionuclides described herein involve emission of high-energy γ-rays, relevant shielding and radiation safety issues are also considered. In particular, the properties and safety considerations associated with the increasingly prevalent PET nuclides 64Cu, 68Ga, 86Y, 89Zr, and 124I are discussed.

Over the last three decades, the success of 99mTc- and 18F-radiolabeled agents such as 99mTc-sestimibi (99mTc-MIBI, Cardiolite) and 99mTc-tetrofosmin (Myoview, GE Healthcare, US) for imaging of myocardial perfusion with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and [18F]-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-d-glucose ([18F]-FDG) as a metabolic marker for use with positron emission tomography (PET) has led scientists to explore the potential of other radionuclides with varying physical properties. Several review articles have discussed the most important factors that influence the choice of radionuclide in the design of new radiopharmaceuticals. 1–7 The Handbook of Radiopharmaceuticals remains one of the most important resources providing comprehensive information on the production of various nuclides, as well as extensive evaluation of the chemistry of conventional radionuclides. 8 An excellent range of electronic resources are available from the National Nuclear Decay Center (Brookhaven National Laboratory) 9 and the Lund University (Sweden)/Lawrence-Berkeley National Laboratory websites. 10

First and foremost, the choice of radionuclide depends on the intended application in diagnostic (PET, SPECT, or radioscintigraphy) or therapeutic agents. Next, the chemical form and in vivo biologic characteristics (including the target, biologic half-life, and stability toward metabolism) of the desired radiopharmaceutical are identified. For example, the chemistry and radiochemistry employed are dependent on whether the radiolabel is to be incorporated into a small molecule-, peptide-, or antibody-based agent. Once the application and chemistries are known, the radionuclide can be selected based on other factors, which include physical decay characteristics such as half-life (t1/2) and decay modes, as well as the availability of a radionuclide, its ease of production, purification, and isolation in a chemical form suitable for further radiochemistry. 1–6,8

As noted by Qaim, inconsistencies in the reported decay characteristics, such as positron (β+) yields and intensities, are prevalent in the literature.11 With continuing preclinical development of radiopharmaceuticals based on unconventional radionuclides, such discrepancies in decay data may prevent accurate quantification of PET images and lead to poor estimation of in vivo dosimetry, thereby hindering efforts toward the clinical translation of new agents. Furthermore, as the use of metalloradionuclides becomes increasingly common, it is important to reconsider radiation shielding requirements associated with the safe handling of potential high-energy γ-ray emitters.

This brief review covers the nuclear decay characteristics of 60 radionuclides for which there is potential application in the development of imaging and therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals. The reader is also referred to an excellent review (and references therein) by Pagani and colleagues that describes the properties and clinical applications of “25 alternative positron-emitting radionuclides.”1 The following discussion provides an up-to-date extension of the aforementioned article and covers a more extensive range of radionuclides. In addition, the potential impact of unconventional PET radionuclides on radiation safety is considered by way of a case study on the increasingly prevalent nuclides 64Cu, 68Ga, 86Y, 89Zr, and 124I.

Radionuclide Production

The radionuclides considered in this review can be subdivided into three main categories (generator, cyclotron, or reactor) based on their method of production (Figure 1). Generator-produced radionuclides are particularly attractive for use in biomedical applications because they are cost-effective and can be used in locations remote from cyclotron or reactor facilities. Introduction of the 99Mo/99mTc generator led to widespread use of 99mTc-labeled agents in both basic science research and clinical SPECT imaging.12–14 However, the facile production and ready availability of the parent radionuclides are essential prerequisites to the development and deployment of generator-based systems. Parent radionuclides for generators usually require the use of nuclear reactors (see below). Cyclotrons are often distinguished based on their maximum proton (Ep) or deuteron (Ed) particle energies. For example, high-energy cyclotrons are classified as accelerators with maximum proton energies, Ep ≥ 30 MeV; medium-energy cyclotrons accelerate particles to energies in the range Ep = 20 to 30 MeV; and low-energy cyclotrons have Ep ≤ 19 MeV and Ed ≤ 10 MeV. Low-energy cyclotrons are the least expensive and most numerous owing to their widespread use in biomedical applications. The most common low-energy transmutation reactions include (p,n), (p,α), (d,n), and (d,α), and the majority of the radionuclides currently under investigation for potential use in the clinic can be produced via these simple nuclear reactions. Owing to their extremely high cost and the numbers of highly skilled workers required to operate a nuclear reactor, these facilities are in general operated at the national level. Prominent reactor facilities in North America include, for example, the Chalk River Laboratory, Ontario, Canada, which is owned and operated by Atomic Energy of Canada Limited and (when fully operational) produces around one-third of the world’s supply of 99Mo for 99mTc generators (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Pictures of (A) a 68Ge/68Ga generator; (B) the focusing magnets; and (C) the multihead target assembly of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center EBCO TR19/9 cyclotron and (D) the core of the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR). Courtesy of David Nickolaus, MURR Center.

Figure 2.

Global supply of 99Mo in 2009. Source: http://www.iaea.org/worldatom/rrdb/.

Radiolabeling Chemistry

Of the 60 radionuclides described in this review (see below), 11 are nonmetals (mostly group VII halogen radionuclides) and the remaining 49 are metalloradionuclides. Fluorine-18 chemistry is dominated by nucleophilic substitution (SN2) reactions, which involve the replacement of leaving groups by the 18F− anion.15 In contrast, labeling with bromine, iodine, and astatine radionuclides usually involves oxidation to give a synthetic equivalent of the cationic species, followed by subsequent radiolabeling of the target molecule by electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions (SEAr) involving histidine or tyrosine amino acid residues (Figure 3). In cases where direct reaction leads to undesirable changes in, for example, the structure, solubility, or function of the radiolabeled compound, preradiolabeling of aromatic reagents (such as Bolton-Hunter reagents) followed by conjugation of these prosthetic groups to the target molecule can be used.16 In contrast, labeling strategies for metalloradionuclides are almost exclusively based on conjugate labeling techniques. Conjugate labeling requires the use of a bifunctional chelating group (Figure 4).6,7,17–19 Bifunctional chelates consist of a multidentate ligand, selected for high thermodynamic and kinetic stability with the desired metalloradionuclide, which has been derivatized with functional groups such as amines (R-NH2), carboxylic acids (R-CO2H), or isothiocyanates (R-NCS), for covalent bonding to biologically active targeting vectors (eg, peptides and antibodies). The use of bioconjugation chemistry in radiochemistry has been the subject of many books and review articles.7,12,16,17,19–22

Figure 3.

Structures of common direct and conjugate-based (prosthetic groups based on Bolton-Hunter compounds) reagents used in the radiohalogenation of small molecules, peptides, and antibodies with Br, I, and At radionuclides. In particular, the reactions with tyrosine and histidine amino acid side chains are shown.

Figure 4.

Selected bifunctional chelates often employed in conjugate labeling strategies.6,17–19

Radionuclides for PET

For PET, the majority of both preclinical and clinical studies focus on the use of just four “conventional” radionuclides, namely 18F and the so-called “bionuclides” 11C, 13N, and 15O. The production routes and physical decay characteristics of these conventional radionuclides are presented in Table 1. The comparatively short half-lives of these four radionuclides, which range from 122.24 seconds for 15O to 109.77 minutes for 18F, can be recognized as either an advantage or a disadvantage depending on the desired application and type of chemistry involved. On the one hand, working with radionuclides that have short half-lives reduces the overall dose exposure of both patients and clinicians and allows repeat imaging studies to be performed on the same day without requiring the patient to remain in hospital overnight. However, the rapid decay of 11C, 13N, and 15O places severe restrictions on the types of chemistry that can be used for radiopharmaceutical preparation. The synthetic routes and purification and drug formulation methods used must be both extremely rapid and efficient to produce a radio-pharmaceutical in these demanding timescales. Despite these challenges, radiochemists have developed highly creative ways of producing a wide range of PET radiotracers using both manual and automated synthesis. Synthetic strategies for the production of 11C, 13N, 15O, and 18F radiopharmaceuticals have been reviewed by Miller and colleagues.15 For 11C, 13N, and 15O, the radiolabeling chemistry often involves direct replacement of an atom within a drug. In the case of 18F, radiolabeling usually relies on nucleophilic substitution reactions, which generate inert C-18F bonds, often replacing C-H bonds in the native compound. We have also discussed the clinical use of selected 18F-labeled PET agents, other than [18F]-FDG, which have the potential to be used to monitor patient response to oncologic therapy before, during, and after treatment.23

Table 1.

| Radionuclide | Half-Life | Decay Mode (% branching ratio) |

Production Route |

E(β +)/keV | β+ End-Point Energy/keV |

Abundance, Iβ+/% |

Eγ/keV (intensity, Iγ/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11C | 1,223.1 (12) s | β+ (100) | 14N(p,α)11C | 385.6 (4) | 960.2 (9) | 99.759 (15) | 511.0 (199.5) |

| 13N | 9.965 (4) m | β+ (100) | 16O(p,α)13N | 491.82 (12) | 1198.5 (3) | 99.8036 (20) | 511.0 (199.6) |

| 15O | 122.24 (16) s | β+ (100) |

l5N(p,n)15O l4N(d,n)15O |

735.28 (23) | 1732.0 (5) | 99.9003 (10) | 511.0 (199.8) |

| 18F | 109.77 (5) m | β+ (100) |

18O(p,n)18F 20Ne(d,α)18F |

249.8 (3) | 633.5 (6) | 96.73 (4) | 511.0 (193.5) |

m = minutes; PET = positron emission tomography.

Unless otherwise stated, standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Generator-Produced PET Radionuclides

The production routes and physical decay properties of generator-produced “unconventional” PET radionuclides are presented in Table 2.8,9 The longer-lived parent radionuclides such as 62Zn (t1/2 = 9.186 h) and 68Ge (t1/2 = 270.95 d) used in generator systems are normally produced by nuclear reactors and typically decay by electron capture (ε) to give daughter radionuclides with shorter half-lives. Of the seven generator-produced PET radionuclides, six are metalloradionuclides and only 122I is a nonmetal. In general, the half-lives of these generator-produced radionuclides are short (on the order of a few minutes) and lie within the range of 1.273 m for 82Rb to 67.71 m for 68Ga and 69.1 m for 110mIn. Similarly, positron yields are typically high, (63% for 110mIn to 97.430% for 62Cu), with alternative decay routes dominated by electron capture.

Table 2.

| Radionuclide | Half-Life | Decay Mode (% branching ratio)* |

Production Route | E(β +)/keV*a | β+ End-Point Energy/keVa |

Abundance, Iβ+/%* |

Eγ/keV (intensity, Iγ/%) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52mMn | 21.1 (2) m | ε + β+ (98.25 [2]) β+ (95.0 [20]) IT (1.75 [2]) |

52Fe/52mMn | 1,174.0 (9) | 2,633.2 (19) | 94.8 (20) | 511.0 (190) 1,434.1 (98.3) |

79 |

| 62Cu | 9.673 (8) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (97.430 [23]) |

62Zn/62Cu | 1,316.0 (24) | 2,926 (4) | 97.200 (20) | 511.0 (194.9) | 80–83 |

| 68Ga | 67.71 (9) m | ε + β+ (100) β+(89.14 [12]) |

68Ge/68Ga | 836.02 (56) | 1,899.1 (12) | 87.94 (12) | 511.0 (178.3) | 25–27 |

| 82Rb | 1.273 (2) m | β+ (95.43 [22]) |

82Sr/82Rb | 1,167.6 (33) 1,534.6 (34) |

2,601 (7) 3,378 (7) |

13.13 (14) 81.76 (17) |

511.0 (190.9) 776.52 (15.1) |

24, 84–87 |

| 110mIn | 69.1 (5) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (63 [4]) |

110Sn/110mIn 110Cd(p,n)110mIn 111Cd(p,2n)110mIn |

1,043 (6) | 2,260 (12) | 62 (4) | 511.0 (125) 657.8 (98) |

88–90 |

| 118Sb | 3.6 (1) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (73.5 [3]) |

118Te/118Sb | 1,188.6 (14) | 2,635 (3) | 73.2 (3) | 511.0 (147) | 91,92 |

| 122I | 3.63 (6) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (78 [6]) |

122Xe/122I | 1,195.3 (24) 1,458.1 (24) |

2,648 (5) 3,212 (5) |

10 (3) 67 (3) |

511.0 (156) 564.1 (18) |

93–96 |

ε = electron capture; IT = isomeric transition; m = minutes.

Where positrons or γ-rays with different energies are emitted, only those with abundance > 10% are listed.

Unless otherwise stated and where available, standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Rubidium-82 is the most prevalent generator-produced radionuclide used in clinical applications, and the 82Sr (t1/2 = 25.55 d)/82Rb generator is widely available.24 For PET centers that do not have access to in-house cyclotron facilities, 82Rb+ ions (which mimic the behavior of K+ ions) provide an economical alternative to the use of [13N]−NH3 or [15O]−H2O for cardiac perfusion imaging. In addition, 82Rb+ has also been used to provide qualitative and quantitative information on the integrity of the blood-brain-barrier, myocardial cell membrane viability, and changes in renal perfusion among other applications.

In recent years, the potential of 68Ga for PET has been recognized. Gallium-68 is an attractive alternative to 18F for radiolabeling small molecules and peptides25 and may be used to replace established 67Ga SPECT agents for quantitative PET. The 68Ge (t1/2 = 270.95 d)/68Ga generator is commercially available and in clinical settings can be used for between 1 and 2 years with two to three elutions per day before being replaced.26–27 Furthermore, the decay properties of 68Ga (t1/2 = 67.71 m), such as a high positron yield (89.14%) and a comparatively low mean β+ kinetic energy (829.5 keV), mean that more elaborate chemical synthesis and purification schemes can be employed without compromising PET image resolution. The versatility of 68Ga as a radionuclide for PET imaging is demonstrated by recent examples in which conjugate labeling methods were used in the design of 68Ga-labeled agents based on small molecules,28 peptides,29 and antibody fragments.30

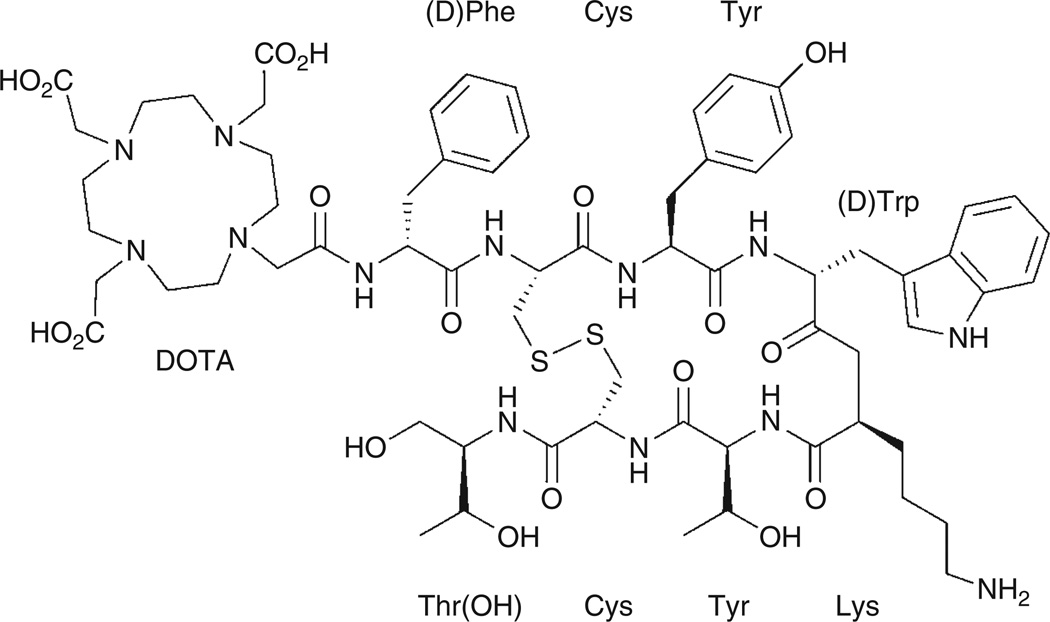

PET with the 68Ga-labeled complex of the ligand 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N′,N″,N‴-tetraacetic acid-D-Phe1-Tyr3-octreotide, [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC, provides one of the most striking examples of the use of an unconventional radionuclide in the design of a targeted radiotracer (Figure 5). [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC is a somatostatin analogue with high in vivo stability that binds to somatostatin receptors. Somatostatin receptors are G-coupled receptor proteins that are known to be abundant on the surface of several human tumors, including neuroendocrine tumors.31–35 In recent clinical studies, Gabriel and colleagues investigated the potential of [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC for use in the diagnosis of primary neuroendocrine tumors and related bone metastases.36–38 They also compared the [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC PET images with other techniques, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and radioscintigraphy (Figure 6). In 51 patients with neuroendocrine tumors, 12 showed no evidence of bone metastases using other available imaging modalities and 37 patients had [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC PET true-positive results for bone metastases. [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC PET results were true-negative for 12 patients who did not have bone metastases, false-positive for one, and false-negative for another, resulting in a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 92%.36

Figure 5.

Structure of the DOTA-TOC ligand used in the preparation of the somatostatin analogue [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC.

Figure 6.

Images of a 56-year-old woman with multiple liver and lymph node metastases. The patient was referred for restaging after surgery and chemotherapy. The CT image shows the presence of liver and lymph node metastases but was negative for bone lesions. A, [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC showed all the visceral metastases, as well as additional osteoblastic and osteolytic bone metastases. Conventional scintigraphy, (B) anterior and (C) posterior views, failed to delineate the majority of bone metastases. Osteoblastic bone lesions were confirmed by [18F]-NaF PET (D). Retrospective CT analysis after image fusion revealed some but not all of these bone metastases.36 Reprinted by permission of the Society of Nuclear Medicine from: Gabriel M, Decristoforo C, Kendler D, et al. 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotide PET in neuroendocrine tumors: comparison with somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and CT. J Nucl Med 2007;48:508–18. Figure 2.

Cyclotron-Produced PET Radionuclides

Small (low-energy) cyclotrons represent the most versatile method for the production of a wide range of unconventional PET radionuclides (Table 3). The physical properties and examples of use of many of these radionuclides have been described elsewhere.1–6

Table 3.

Physical Decay Characteristics of Various “Nonstandard” Cyclotron-Produced Radionuclides for Positron Emission Tomography8,9

| Radionuclide | Half-Life (error) |

Decay Mode (% branching ratio)* |

Production Route | E(β +)/keV | β+ End-Point Energy/keV |

Abundance, Iβ+/% |

Eγ/keV (intensity, Iγ/%) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34mCI | 14.60 (5) h | ε + β+ (55.4 [6]) β+ (54.3 [8]) IT (44.6 [6]) |

34S(p,n)34mCI 32S(α,pn)34mCI |

554.81 (24) 1,099.01 (21) |

1,311.43 (8) 2,488.08 (8) |

25.6 (5) 28.4 (7) |

511.0 (108.5) 146.4 (40.5) 1,176.6 (14.1) 2,127.5 (42.8) 3,304.0 (12.3) |

97,98 |

| 38K | 7.636 (18) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (99.53 [5]) |

38Ar(p,n)38K | 1,212.08 (20) | 2,724.4 (4) | 99.333 (13) | 511.0 (199.1) 2,167.5 (99.9) |

1,99,100 |

| 45Ti | 184.8 (5) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (84.82 [13]) |

45Sc(p,n)45Ti | 1,040.1 (5) | 438.93 (22) | 84.80 (13) | 511.0 (169.6) | 101–103 |

| 51Mn | 46.4 (1) m | ε + β+ (100%) β+ (97.08 [7]) |

50Cr(d,n)51Mn natCr(p,x)51Mn |

963.67 (19) | 2,185.5 (4) | 96.86 (7) | 511.0 (194.17) | 99,104 |

| 52Mn | 5.591 (3) d | ε + β+ (100) β+ (29.6 [4]) |

natCr(p,xn)52Mn | 241.8 (9) | 575.6 (19) | 29.6 (4) | 511.0 (59.2) 744.2 (90.0) 935.5 (94.5) 1,434.1 (100.0) |

105 |

| 52Fe | 8.275 (8) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (99.58) |

natNi(p,x)52Fe | 1,990 (64) | 4,473 (6) | 99.58 | 511.0 (199.2) 621.7 (51) 869.9 (93) 929.5 (100) 1,416.1 (48) |

2,8, 106–113 |

| 55Co | 17.53 (3) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (76 [3]) |

56Fe(p,2n)55Co 54Fe(d,n)55Co 58Ni(p,α)55Co |

435.68 (20) 648.98 (20) |

1,021.3 (4) 1,498.5 (4) |

25.6 (15) 46 (3) |

511.0 (152) 931.1 (75) 1,408.5 (16.9) |

8,114–118 |

| 60Cu | 23.7 (4) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (93 [4]) |

60Ni(p,n)60Cu | 872.0 (10) 1,324.9 (10) |

1,980.8 (21) 2,946.0 (21) |

49.0 (23) 15.0 (12) |

511.0 (185) 826.4 (21.7) 1,332.5 (88.0) 1,791.3 (45.4) |

119,120 |

| 61Cu | 3.333 (5) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (61 [5]) |

61Ni(p,n)61Cu 60Ni(d,n)61Cu |

523.69 (54) | 1,215.2 (12) | 51 (5) | 511.0 (123) 656.0 (10.8) |

119–122 |

| 64Cu | 12.701 (2)h | ε + β+(61.5[3]) β+(17.60 [22]) β− (38.5 [3]) |

64Ni(p,n)64Cu 67Zn(p,α)64Cu |

278.21 (9) | 653.03 (20) | 17.60 (22) | 511.0 (35.2) | 46,123 |

| 66Ga | 9.49 (7) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (56.0 [15]) |

66Zn(p,n)66Ga 63Cu(α,n)66Ga |

1,904.1 (15) | 4,153 (3) | 50.0 (15) | 511.0 (112) 1,039.2 (36.9) 2,751.75 (23.3) |

8,28, 124–127 |

| 71As | 65.28 (15) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (28.3 [8]) |

70Ge(p,γ)71As | 352.0 (18) | 816 (4) | 27.9 (8) | 511.0 (56.5) | 128 |

| 72As | 26.0 (1) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (87.8 [23]) |

70Ge(α,2n)72Se/ 72As 72Ge(p,n)72As |

1,117.0 (19) 1,528.5 (19) |

2,500 (4) 3,334 (4) |

64.2 (15) 16.3 (17) |

511.0 (176) 834.0 (79.5) |

129–133 |

| 74As | 17.77 (2) d | ε + β+ (66 [2]) β+ (29 [3]) β− (34 (2)%) |

74Ge(p,n)74As 73Ge(d,n)74As |

408.0 (8) | 944.6 (17) | 26.1 (22) | 511.0 (58) 595.8 (59) 634.8 (15.4) |

129 |

| 75Br | 96.7 (13) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (73 [5]) |

76Se(p,2n)75Br | 758 (7) | 1,721 (14) | 52 (3) | 511.0 (146) | 134 |

| 76Br | 16.2 (2) h | ε + β+ (100%) β+ (55 [3]) |

76Se(p,n)76Br 75As(α,3n)76Br |

1,532 (8) | 3,383 (9) | 25.8 (19) | 511.0 (109) 559.1 (74) 657.0 (15.9) 1,853.7 (14.7) |

135,136 |

| 82mRb | 6.472 (6) h | ε + β+ (100%) β+ (21.2 [16]) |

82Kr(p,n)82mRb | 352 (11) | 798 (7) | 19.7 (16) | 511.0 (42) 554.4 (62.4) 619.1 (38.0) 698.4 (26.3) 776.5 (84.4) 827.8 (21.0) 1,044.1 (32.1) 1,317.4 (23.7) 1,474.9 (15.5) |

137–139 |

| 86Y | 14.74 (2) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (31.9 [21]) |

86Sr(p,n)86Y | 535 (7) | 1,221 (14) | 11.9 (5) | 443.1 (16.9) 511.0 (64) 627.7 (36.2) 703.3 (15) 777.4 (22.4) 1,076.6 (82.5) 1,153.0 (30.5) 1,854.4 (17.2) 1,920.7 (20.8) |

47 |

| 89Zr | 78.41 (12) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (22.74 [24]) |

89Y(p,n)89Zr | 395.5 (11) | 902 (3) | 22.74 (24) | 511.0 (45.5) 909.2 (99.0) |

39–43, 45 |

| 90Nb | 14.60 (5) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (51.2 [18]) |

90Zr(p,n)90Nb | 662.2 (18) | 1,500 (4) | 51.1 (18) | 511.0 (102) 1,129.2 (92.7) 2,186.2 (18.0) 2,319.0 (82.0) |

140,141 |

| 94mTc | 52.0 (10) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (70.2 [4]) |

94Mo(p,n)94mTc | 1,094 | 2,439 (5) | 67.6 (4) | 511.0 (140.3) 871.1 (94.2) |

48, 142–146 |

| 120I | 81.6 (2) m | ε + β+ (100) β+(68.2 [12]) |

l22Te(p,3n)120I | 1,845.0 (72) 2,099.3 (70) |

4,033 (15) 4,593 (15) |

29.3 (7) 19.0 (7) |

511.0 (136.5) 560.4 (69.6) 1,523.0 (10.9) |

1 |

| 124I | 4.1760 (3) d | ε + β+ (100) β+(22.7 [13]) |

l24Te(p,n)124I | 687.04 (85) 974.74 (85) |

1,534.9 (19) 2,137.6 (19) |

11.7 (10) 10.7 (9) |

511.0 (45) 602.7 (62.9) 722.8 (10.4) 1,691.0 (11.2) |

49, 147–149 |

ε = electron capture; IT = isomeric transition; m = minutes.

Where positrons or γ-rays with different energies are emitted, only those with abundance > 10% are listed.

Unless otherwise stated and where available, standard deviations are given in parentheses.

With careful optimization of the cyclotron targetry (including the chemical composition and standard state of the target material, target thickness, and geometry) and particle beam parameters such as particle energy and beam current, as well as irradiation times, high production yields (measured in units of mCi/µA.h) can be obtained for many of the radionuclides given in Table 3.11 In particular, careful selection of the irradiation parameters can minimize the production of unwanted radionuclidic impurities. For example, 89Zr is a promising PET radionuclide for labeling monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for use in immuno-PET imaging, and its production via the 89Y(p,n)89Zr transmutation reaction using 100% naturally abundant 89Y thin metal foils has been studied in detail by several groups.39–44 However, many previous attempts to prepare 89Zr in high radionuclide, radiochemical, and chemical purity have suffered from difficulties arising from the complex separation chemistry and contamination from the longer-lived nuclides 88Zr (t1/2 = 83.4 days) and 88Y (t1/2 = 106.626 days).44 Our recent studies demonstrated that by optimizing the irradiation parameters (15 MeV, 15 µA, 10° angle of incidence using a thin-foil 89Y plate of 0.1 mm and > 99.9% purity), 89Zr can be produced in high yield (2- to 3-hour irradiations give 45 to 60 mCi with a yield of 1.52 ± 0.11 mCi/µA.h) and high specific activity (5.28–13.43 mCi/µg).45 The use of γ-ray spectroscopy also showed that the isolated 89Zr samples were free from radionuclide contamination. Similar optimizations have been reported for many of the radionuclides in Table 3, including 64Cu, 86Y, 94mTc, and 124I.46–49 Representative γ-ray spectra of 18F, 86Y, 124I, and 89Zr are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Stack plot showing the γ-ray emission spectra of the positron-emitting radionuclides 18F, 86Y, 124I, and 89Zr. Details of the emission characteristics are presented in Table 1 and Table 3.

Case Studies: 64Cu, 89Zr, and 124I for Immuno-PET

In this section, three case studies on the use of different PET radionuclides for labeling of mAbs for immuno-PET imaging are presented. Labeling antibodies and immunoglobulin (IgG) fragments is most frequently achieved by using conjugate labeling techniques. In particular, functionalization of mAbs with DOTA or DTPA ligands has been used to produce radioimmunoconjugates for both imaging and radioimmunotherapy (RIT). Boswell and Brechbiel have provided a recent commentary on the chemical, biologic, and regulatory challenges encountered during efforts toward the clinical translation of radioimmunoconjugates. 50 Needless to say, the choice of radionuclide is an extremely important factor in determining the overall properties and therefore the success or failure of any new radioimmunoconjugate. For example, 18F and 68Ga are inappropriate for labeling intact (150 kDa) IgG molecules because their short half-lives would mean that almost all of the activity would have decayed before optimal biodistribution of the radiotracer occurs. Likewise, aside from any incompatibilities in their chemistries, radionuclides such as 52Mn (t1/2 = 5.591 days) and 74As (t1/2 = 17.77 days) are inappropriate choices for mAb labeling because their long-lives would likely mean poor counting statistics for PET and increased radiation dose to the patient. For these and other reasons, research has focused on the use of 64Cu, 89Zr, and 124I for labeling mAbs, and several recent clinical investigations have explored their potential use in immuno-PET.51–54 Three examples of successful clinical translation are presented below.

In the first phase I/II clinical study involving the use of a 64Cu-labeled antibody, Philpott and colleagues compared [18F]-FDG and [64Cu]-BAT-2IT-1A3 mAb uptake in 36 patients with suspected advanced primary or metastatic colorectal cancer.51 Their studies showed that [64Cu]-BAT-2IT-1A3 was more specific for detecting colorectal tumors than [18F]-FDG. [18F]-FDG showed false-positive indications in patients with inflammatory lesions. The sensitivity of [64Cu]-BAT-2IT-1A3 was found to be 86% per patient and 71% per lesion, which was improved over radioimmunoscintigraphy using [111In]-1A3 (76% per patient and 63% per lesion).55 Further preclinical studies also investigated the therapeutic potential of BAT-2IT-1 A3 radiolabeled with either 64Cu or 67Cu.56 The results demonstrated that 64Cu has the potential for use in the design of RIT agents.

The decay characteristics of 89Zr are particularly attractive for use in immuno-PET because the half-life of 78.41 hours is very similar to the time required for optimal biodistribution of full intact (150 kDa) IgG antibodies and the decay has few high-energy γ-ray emissions, which decreases patient exposure.57 The clinical use of 89Zr-labeled mAbs has been pioneered by the research teams at the Vrije University Medical Centre (Amsterdam, the Netherlands). At present, conjugation methods are based on the use of desferrioxamine B (DFO) (see Figure 4),58–62 and in 2006, Perk and colleagues reported the first human immuno-PET images recorded in a pilot study comparing the uptake of [18F]-FDG with [89Zr]-Zevalin in a B-cell CD20-positive patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.52 Later in the same year, Borjesson and colleagues described the results from the first clinical trial of [89Zr]-DFO-labeled U36, a chimeric anti-CD44v6 mAb used for the detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck.53 Twenty patients received 75 MBq of [89Zr]-DFO-U36 coupled to 10 mg of the mAb, and their results indicated that 89Zr-immuno-PET detected all primary tumors (n = 17) as well as lymph node metastases with high sensitivity (72%) and accuracy (93%). Immuno-PET images were acquired up to 144 hours after postinjection (Figure 8), and the data were comparable to diagnostic results obtained by using [18F]-FDG PET, CT, and MRI in the same patients. Further studies on the use of 89Zr-labeled mAbs are currently under way in both Europe and the United States.

Figure 8.

Immuno-PET images with [89Zr]-DFO-U36 of a head and neck cancer patient with a tumor in the left tonsil (large arrow) and lymph node metastases (small arrows) at the left (levels II and III) and right (level 11) sides of the neck. Images were obtained 72 hours postinjection. A, Sagittal; B, transaxial; and C, coronal image.53 Reprinted with permission from the American Association for Cancer Research: Borjesson PKE, Jauw YWS, Boellaard R, et al. Performance of immunopositron emission tomography with zirconium-89-labeled chimeric monoclonal antibody U36 in the detection of lymph node metastases in head and neck cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:2133–40. Figure 2.

Iodine-124 provides the third example of an unconventional PET radionuclide that is attracting great attention for labeling mAbs. The high-energy γ-ray emissions that occur on 124I decay mean that dosimetry with this radionuclide may be a limiting factor in its clinical impact (see Table 3 and Figure 7). However, standardized iodination protocols mean that in the immediate future, 124I is set to play a prominent role in preclinical and clinical immuno-PET studies.

Divgi and colleagues recently completed a phase I clinical investigation of [124I]-cG250, a chimeric mAb directed against carbonic anhydrase IX.54 Their studies looked at radiotracer uptake in 26 patients diagnosed with clear cell renal carcinoma, the most common and aggressive form of renal cancer. Patients received a single intravenous infusion of 185 MBq/10 mg of [124I]-cG250, and the immuno-PET results showed that 15 of 16 clear cell carcinomas were identified accurately. In addition, all nine non-clear cell renal masses were negative for tracer uptake. The sensitivity of [124I]-cG250 immuno-PET for clear cell renal carcinoma in this trial was 94%; the negative predictive value was 90%, and specificity and positive predictive accuracy were both 100%. The conclusions from the study were that immuno-PET with [124I]-cG250 can identify accurately clear cell renal carcinoma, and a negative scan was highly predictive of a less aggressive phenotype. Stratification of patients with renal masses by [124I]-cG250 PET can identify aggressive tumors and help decide treatment.

None of the results described in the three case studies above could have been achieved without the use of unconventional radionuclides. These examples also illustrate the requirement for scientists and clinicians to continue the development of alternatives to [18F]-FDG and other 18F-labeled radiotracers.

Radionuclides for SPECT

The physical decay characteristics of four low-energy γ-rayemitting radionuclides for potential use in the design of SPECT agents are presented in Table 4. Two 111In-labeled antibodies, OncoScint for anti-TAG-72 imaging of colorectal and ovarian cancer and ProstaScint for anti–prostate-specific membrane antigen (anti-PSMA) imaging of prostate cancer, have been approved for use in humans.50 The simple reason for the dominance of 99mTc is that the nuclear decay characteristics of 99mTc are almost ideal for SPECT. Technetium-99m decays by isomeric transition (IT) with a half-life of 6.01 hours and emits γ-rays at 140 keV (89%). As introduced above, readily available 99Mo/99mTc generators produce sterile pertechnetate, 99mTcO4− (aq.) in saline on demand, which facilitates in-house radiopharmaceutical production and has made 99mTc the radionuclide of choice for SPECT.63

Table 4.

Physical Decay Characteristics of Various γ-Ray Emitting Radionuclides for Use in SPECT

| Radionuclide | Half-Life (error) | Decay Mode (% branching ratio) |

Production Route | Enp/keV | Abundance, Inp/% |

Eγ/keV | Intensity, Iγ/% |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 67Ga | 3.2617 (5) d | ε (100) |

natZn(p,x)67Ga 68Zn(p,2n)67Ga |

Auger L (0.99) Auger K (7.35) CE – K (83.606) |

168.3 (21) 60.7 (9) 29.1 (9) |

91.265 (5) 93.310 (5) 184.576 (10) 208.950 (10) 300.217 (10) 393.527 (10) |

3.11 (4) 38.81 (3) 21.410 (10) 2.460 (10) 16.64 (12) 4.56 (24) |

125,150–153 |

| 99mTC | 6.01 (1) h | β− (0.0037 [6]) IT (99.9963 [6]) |

99Mo/99mTc | CE – K (1.6286 [11]) Auger L (2.17) |

74.595 10.32 (6) |

140.511 (1) | 89.06 | 12–14 |

| 111In | 2.8047 (4) d | ε (100) |

111Cd(p,n)111m,gIn 112Cd(p,2n)111m,gIn |

Auger L (2.27) Auger K (19.3) CE – K (144.57) CE – K (218.64) |

100.4 (4) 15.5 (4) 8.07 (8) 4.95 (5) |

171.28 (3) 245.35 (4) |

90.7 (9) 94.1 (10) |

88 |

| 123I | 13.2234 (19) h | ε (100%) |

124Xe (p,2n)123Cs → 123Xe→ 123I 124Xe (p,pn)123I 123Te(p,n)123I |

Auger L (3.19) Auger K (22.7) CE – K (127.16) |

95.1 (6) 12.4 (4) 13.612 |

158.97 (5) 528.96 (5) |

83.3 1.39 (4) |

154–157 |

ε = electron capture; IT = isomeric transition; SPECT = single-photon emission computed tomography.

Unless otherwise stated, standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Despite promising results with 67Ga-, 111In-, and 123I-labeled agents, 99mTc continues to dominate the field of SPECT.12–14 Recent press releases from the Society of Nuclear Medicine (SNM) have reported that 99mTc is currently used in approximately 70 to 80% of all radiodiagnostic scans in over 300,000 procedures per week in the United States alone. However, in 2009, nuclear medicine has witnessed a dramatic shortfall in the supply of the parent radionuclide 99Mo. This shortage arose owing to downtime of the NRU reactor at Chalk River, Canada, and the High Flux Reactor in Petten, the Netherlands, and reduced global 99Mo output levels to less than 30% of normal—an approximate 40% shortfall in production. The lack of availability of 99Mo for 99mTc generators has prompted nuclear medicine departments to use PET alternatives to 99mTc-SPECT. For example, many departments have used [18F]-NaF for bone imaging in place of 99mTc-MDP. If 99mTc-SPECT is to remain a dominant force in the future of nuclear imaging, new alternatives for the production of 99Mo are urgently required. This high demand has been recognized by the US Congress, which passed the American Medical Isotopes Production Act of 2009 (H.R. 3276). This act will provide the Department of Energy with some $163 million to support US-based production of 99Mo and should help alleviate future supply issues when several current facilities are decommissioned.

Radionuclides for Therapy

Several radionuclides that decay with the emission of Auger electrons and β− or α-particles have the potential to be used in the design of radiotherapeutic agents (Table 5 and Table 6). Of particular interest are those elements for which PET/therapeutic radionuclide pairs exist, such as 86Y/90Y, 60,61,62,64Cu/66,67Cu, and 124I/131I. These radionuclides offer the potential for the development of chemically identical agents for imaging and site-directed radiotherapy. For example, quantitative PET with a 64Cu-labeled radiotracer could be used to predict accurate dosimetry for subsequent treatment with the 67Cu-labeled species. Furthermore, the PET radiotracer could also be used to monitor the efficacy of the radiotherapy treatment. It should be noted that 64Cu also decays via β− particle emission (38.5%) and its therapeutic potential has been investigated.64–66 This section provides a brief description of several of the more promising therapeutic radionuclides.

Table 5.

Physical Decay Characteristics of Various β-Emitting Radionuclides for Potential Use in Radiotherapy

| Radionuclide | Half-Life (error) | Decay Mode (% branching ratio) |

Enp/keV | Abundance, Inp/% |

Eγ/keV | Intensity, Iγ/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32P | 14.263 (3) d | β−(100%) | 1,710.48 (22) | 100 | — | — |

| 47Sc | 3.3492 (6) d | β−(100%) | 440.9 (19) 600.3 (19) |

68.4 (6) 31.6 (6) |

159.381 (15) | 68.3 (4) |

| 66Cu | 5.120 (14) m | β−(100%) | 1,602.8 (12) 2,642.0 (12) |

9.01 (9) 90.77 (9) |

1,039.2 (2) | 9.23 |

| 67Cu | 61.83 (12) h | β−(100%) | 168.2 (15) 377.1 (15) 468.4 (15) 561.7 (15) |

1.10 (11) 57 (6) 22.0 (22) 20.0 (22) |

91.266 (5) 93.311 (5) 184.577 (10) |

7.00 (10) 16.10 (20) 48.7 (3) |

| 89Sr | 50.53 (7) d | β−(100) | 1,495.1 (22) | 99.99036 (5) | — | — |

| 90Y | 64.00 (21) h | β−(100) | 2280.1 (16) | 99.9885 (14) | — | — |

| 105Rh | 35.36 (6) h | β−(100) | 248 (3) 261 (3) 567.2 (25) |

19.7 (5) 5.2 (4) 75.0 (6) |

306.1 (2) 318.9 (1) |

5.1 (3) 19.1 |

| 111Ag | 7.45 (1) d | β−(100) | 694.7 (14) 1,036.8 (14) |

7.1 (5) 92 (5) |

343.12 (2) | 6.7 |

| l17mSn | 13.60 (4) d | IT (100) | Auger L (2.95) Auger K (21.0) CE-K (126.82) CE-K (129.36) CE-L (151.56) |

91.8 (5) 10.7 (3) 64.9 (4) 11.699 26.16 (14) |

156.02 (3) 158.56 (2) |

2.114 (12) 86.4 |

| 131I | 8.0252 (6) d | β−(100) | 333.8 (6) 606.3 (6) |

7.23 (10) 89.6 (8) |

284.305 (5) 364.489 (5) 636.989 (4) |

6.12 (6) 81.5 (8) 7.16 (10) |

| 149Pm | 53.08 (5) h | β−(100) | 785 1,048 |

3.40 24 |

285.95 | 3.10 |

| 153Sm | 46.50 (21) h | β−(100) | 634.7 (7) 704.4 (7) 807.6 (7) |

31.3 (9) 49.4 (18) 18.4 (17) |

103.18 | 29.25 |

| 166Ho | 26.80 (2) h | β−(100) | 1,773.3 (11) 1,853.9 (11) |

48.7 (21) 50.0 (21) |

80.574 (8) | 6.71 (8) |

| 177Lu | 6.647 (4) d | β−(100) | 177.0 (8) 385.3 (8) 498.3 (8) |

11.61 (11) 9.0 (5) 79.4 (5) |

112.9 208.4 |

6.17 (7) 10.36 |

| 186Re | 3.7183 (11) d | ε (7.47 [10]) β−(92.53 [10]) |

Auger L (6.53) 932.3 (9) 1,069.5 (9) |

4.96 (10) 21.54 (11) 70.99 (14) |

137.157 (8) | 9.47 (3) |

| 188Re | 17.0040 (22) h | β−(100) | 1,965.4 (4) 2,120.4 (4) |

26.3 (5) 70.0 (5) |

155.041 (4) | 15.61 (18) |

| 195mPt | 4.010 (5) d | IT (100) | Auger L (7.24) Auger K (51.0) CE-L (17.01) CE-K (20.505) CE - M (27.59) CE-K (51.11) CE-L (85.02) CE-L (115.62) CE-M (126.20) |

140 (4) 3.3 (4) 69 (6) 65 (5) 16.0 (13) 13.4 (9) 11.5 (8) 61 (4) 19.3 (14) |

98.90 (2) 129.5 (2) |

11.7 (8) 2.90 (21) |

ε = electron capture; IT = isomeric transition; m = minutes.

Unless otherwise stated, standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Table 6.

Physical Decay Characteristics of Various α-Particle-Emitting Radionuclides for Potential Use in Radiotherapy

| Radionuclide | Half-Life (error) | Decay Mode (% branching ratio) |

Eα/keV | Abundance, Iα/% | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 212Bi | 60.55 (6) m | α (35.95 [6]) β− (64.06 [6]) |

6,050.78 (3) 6,089.88 (3) |

25.13 (7) 9.75 (5) |

158–162 |

| 213Bi | 45.59 (6) m | α (2.20 [10]) β− (97.80 [10]) |

5,549 (10) 5,869 (10) |

0.15 (3) 1.94 (4) |

163 |

| 211At | 7.214 (7) h | α (41.80 [8]) ε (58.20 [8]) |

5,869.5 (22) | 41.80 | 164–166 |

| 225Ac | 10.0 (1) d | α (100) | 5,637 (2) 5,724 (3) 5,732 (2) 5,790.6 (22) 5,792.5 (22) 5,830 (2) |

4.4 (3) 3.1 (5) 8.0 (5) 8.6 (9) 18.1 (20) 50.7 (15) |

68,69, 167–170 |

| 230U | 20.8 (21) d | α (100) | 5,817.5 (7) 5,838.4 (7) |

32.00 (20) 67.4 (4) |

171–173 |

ε = electron capture; m = minutes.

Unless otherwise stated, standard deviations are given in parentheses.

β-Emitting Radionuclides

Yttrium-90 and 131I are arguably the most important radionuclides for β-therapy. In 2002 and 2003, two anti-CD20 radioimmunoconjugates, [90Y]-Zevalin and [131I]-Bexxar, were approved for clinical use in the RIT treatment of B-cell lymphoma.50 In addition, many ongoing clinical trials are aimed at assessing the therapeutic efficacy of 90Y- or 131I-labeled antibodies in the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, glioblastoma, colorectal, prostate, and renal cancers, among others.67 At present, 32P, 153Sm, 177Lu, and 188Re radionuclides (among others) are being used for β-therapy in ongoing clinical trials. Researchers at the Weill Medical College of Cornell University in New York City are conducting a phase II trial studying the therapeutic efficacy of [177Lu]-labeled J591, an anti-PSMA antibody, in patients with prostate cancer (Clinical Trial #NCT00859781).

It is evident that the potential therapeutic value of many unconventional radionuclides has yet to be explored. Much effort is still required to overcome the barriers that currently inhibit the translation of agents that show promise in preclinical studies to full clinical trials.50

α-Emitting Radionuclides

Over the last decade, many groups have focused attention on the use of α-emitting radionuclides in the design of potential therapeutic agents.68–76 The physical decay properties of five α-emitting radionuclides are presented in Table 6. Radionuclides that emit α-particles are most often heavy-metal elements. The rationale for investigating α-therapy stems from the extremely high ionizing potential of α-particles and their concordant short range (< 50 µm) in tissue. If a radiopharmaceutical can be designed to deliver the α-emitter inside the cell (and preferably inside the cell nucleus), then the high linear energy transfer has the potential to cause irreparable damage to DNA and induce cellular apoptosis. Unlike β-particles, which have an energy-dependent range in tissue of between 0.5 and 10 mm, α-particles are less likely to induce damage to surrounding tissue (so-called “crossfire” damage). Decreased crossfire leads to reduced radiotoxicity and more favorable (low) dosimetry for background tissues.

At present, researchers at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the National Cancer Institute are conducting two separate phase I/II clinical trials investigating the efficacy of α-RIT with 213Bi-labeled (NCT00014495) and 225Ac-labeled (NCT00672165) HuM195, a humanized anti-CD33 antibody for treatment of patients with leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. In combination with β-emitters such as 90Y or 131I, HuM195 was found to be unsuitable for use in humans because the increased range of β-particles in tissue leads to high radiation doses and extensive damage to normal bone marrow cells. When [213Bi]-HuM195 was tested in patients, the phase I study found that the α-RIT agent destroyed leukemia cells selectively, with very few side effects. However, [213Bi]-HuM195 is difficult to administer to patients because of the short radioactive half-life (t1/2 = 45.59 minutes). Therefore, further studies using 225Ac(t1/2 = 10.0 days) were initiated. Actinium-225 is also more potent than 213Bi; 225Ac can emit six high-energy α-particles with non-negligible intensities, and experiments showed that [225Ac]-HuM195 has the potential to be approximately 1,000 times more potent than [213Bi]-HuM195.67

Again, the lower dosimetry of α-emitting radionuclides demonstrates how the choice of radionuclide is crucial in determining the efficacy of a radiopharmaceutical. The results from these initial trials will facilitate additional studies using α-therapy.

Radiation Safety for PET

With the increased availability of unconventional radionuclides and gradual translation of promising agents to clinical trials, it is important to reconsider basic radiation safety protocols. In 2006, the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) Task Group 108 (TG 108) provided a comprehensive summary of the issues that need to be considered for PET and PET/CT shielding of nuclear medicine facilities. 77 The AAPM noted that there has been a “recent explosion of interest in PET as a diagnostic imaging modality.” 77 Although their recommendations focused on the use of 18F, they cautioned that PET radionuclides “that are longer lived and have high-energy gamma emissions in addition to the annihilation radiation might not be adequately shielded by a facility designed for 18F imaging.” 77 The γ-ray spectra shown in Figure 7 and the emission data in Table 3 provide a graphic illustration of the need for explicit consideration of high-energy γ-ray emissions (> 511.0 keV) when working with unconventional radionuclides.

In our recent studies involving the use of 86Y, 89Zr, and 124I, we found that only incomplete shielding data for these radionuclides was known. Furthermore, the values of important shielding parameters including Γ constants and the tenth-value layer (TVL) in lead were found to vary widely. For example, Table 7 lists Γ constants for 18F, 68Ga, 82R, 86Y, 89Zr, and 124 I obtained from various sources, including the Handbook of Health Physics and Radiological Health (conventionally referred to as the Radiation Health Handbook), the AAPM TG 109, values calculated using MicroShield (V6.02, Grove Software Inc., Lynchburg, VA), and values estimated from our own field measurements. 77, 78 In addition, TVLs (in centimeters of lead [cmPb]) for selected PET radionuclides have also been estimated by using MicroShield. It should be noted that the TVL values reported also take into account buildup effects. Buildup can be described as the ratio of the primary and scattered radiation measured at a point compared to the primary radiation and must be included in shielding calculations to avoid overestimating the degree of attenuation provided by a given shield.

Table 7.

Calculated Γ Constants (µ Sv m2 MBq−1 h−1) and Tenth-Value Layers/cmPb78

| Γ Constants/µ Sv m2 MBq−1 h−1 | Shipping Container Capacities | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radionuclide | RHH | AAPMTG10877 | MicroShield | MicroShield Ratio to 18F |

Field Data | TVL/cmpb | Estimated Maximum Activity on Contact/mCi |

Estimated Maximum Activity @ 1 m/ mCi |

| 18F | 0.188 | 0.143 | 0.144 | 1 | 0.192 | 1.6 | 2,429 | 1,105 |

| 64Cu | 0.036 | 0.027 | 0.029 | 0.20 | NM | 1.7 | — | — |

| 68Ga | 0.179 | 0.134 | 0.137 | 0.95 | NM | 1.7 | — | — |

| 82Rb | 0.210 | 0.159 | 0.158 | 1.10 | NM | 1.7 | — | — |

| 86Y | 0.629 | — | 0.455 | 3.16 | 0.514 | 3.8 | 15 | 8 |

| 89Zr | 0.266 | — | 0.159 | 1.10 | 0.188 | 3.2 | 55 | 36 |

| 124I | 0.205 | 0.185 | 0.143 | 0.99 | 0.205 | 3.1 | — | — |

AAPM = American Association of Physicists in Medicine; NM = not measured; RHH = Radiation Health Handbook; TVL = tenth-value layer.

The purpose of radiation shielding is to attenuate radiation by scattering, and in doing so, protect radiation workers by reducing their exposure and overall dose rates. Therefore, adequate shielding is of paramount importance in all cyclotron and nuclear medicine facilities. The design of appropriate shielding requires the use of accurate Γ constant and TVL numbers. However, as the numbers shown in Table 7 demonstrate, reported values of Γ constants vary substantially. In response, the AAPM TG 108 suggested that owing to its relationship to regulatory dose limits, the effective dose equivalent value is a more appropriate parameter than the Γ constant for use in the design of shielding requirements.

In terms of radiation protection, corralling all PET radionuclides into a 511.0 keV category is inappropriate. For example, the TVL estimates for 18F, 68Ga, 86Y, 89Zr, and 124I are 1.6, 1.7, 3.8, 3.2, and 3.1 cm of lead, respectively (see Table 7). Despite the approximate fivefold decrease in 511.0 keV γ-ray emission intensities (owing to lower positron yields) for 86Y, 89Zr, and 124I versus 18F, the TVLs are approximately twofold higher. In our work with 86Y, 89Zr, and 124I, we also observed that cyclotron operators and radiochemists working in facilities designed for 18F experience large increases in occupational doses when handling these radionuclides. These exposure increases occur despite the fact that, typically, experiments with 86Y, 89Zr, or 124I involve lower amounts of activity (ca. 1–25 mCi) than the initial amount of 18 F activity used in the synthesis of a single clinical agent (ca. 400–500 mCi). Furthermore, shipping containers currently designed for large quantities of 18F (ca. 2,500 mCi) consequently hold much smaller amounts of these higher-energy radionuclides (see Table 7).

The caveat of these studies is that current facilities, which have been designed for 18F (511.0 keV) emissions, may not be optimal for use with many of the PET radionuclides that are now being used on a regular basis. In the future, higher-energy γ-rays must be accounted for in the design of the next generation of radiochemistry and nuclear medicine facilities.

Summary and Future Directions

With advances in cyclotron targetry, radiochemistry, and bioconjugation methods, the table of available radionuclides with potential application in the production of diagnostic and/or therapeutic agents continues to expand. Owing to the slow pace of clinical translation, the inherent inertia of many clinicians in embracing new technologies, and the difficulties associated with reimbursement for nuclear medicine techniques, [18F]-FDG- and 99mTc-labeled agents will remain dominant in the immediate future. However, many of the new radio-pharmaceuticals currently under development, particularly those agents based on 64Cu, 89Zr, 124I and 225Ac radionuclides, are showing great promise. As more clinical trials deliver successful results, these “unconventional” radionuclides are set to play an increasingly important role in the future of nuclear medicine and may eventually be considered “conventional.”

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure of authors: This work was supported by the Office of Science (BER), US Department of Energy (to J.S.L.).

Biography

Footnotes

Financial disclosure of reviewers: None reported.

References

- 1.Pagani M, Stone-Elander S, Larsson SA. Alternative positron emission tomography with non-conventional positron emitters: effects of their physical properties on image quality and potential clinical applications. Eur J Nucl Med. 1997;24:1301–1327. doi: 10.1007/s002590050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welch MJ, Kilbourn MR, Green MA. Radiopharmaceuticals labeled with short-lived positron-emitting radionuclides. Radioisotopes. 1985;34:170–179. doi: 10.3769/radioisotopes.34.3_170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McQuade R, Rowland DJ, Lewis JS, Welch MJ. Positron-emitting isotopes produced on biomedical cyclotrons. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:807–818. doi: 10.2174/0929867053507397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blower P. Towards molecular imaging and treatment of disease with radionuclides: the role of inorganic chemistry. Dalton Trans. 2006:1705–1711. doi: 10.1039/b516860k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis JS, Singh RK, Welch MJ. Long lived and unconventional PET radionuclides. In: Pomper MG, Gelovani JG, editors. Molecular imaging in oncology. New York: Informa Healthcare USA Inc; 2009. pp. 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nayak TK, Brechbiel MW. Radioimmunoimaging with longer-lived positron-emitting radionuclides: potentials and challenges. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:825–841. doi: 10.1021/bc800299f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu S. The role of coordination chemistry in the development of target-specific radiopharmaceuticals. Chem Soc Rev. 2004;33:445–461. doi: 10.1039/b309961j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welch MJ, Redvanly CS, editors. Handbook of radiopharmaceuticals: radiochemistry and applications. New York: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brookhaven National Laboratory. [accessed October 1,2009];National Nuclear Decay Center. Available at: http://wwwnndcbnlgov/

- 10.Lund University, Lawrence-Berkeley National Laboratory. [accessed October 1,2009]; Available at: http://nucleardatanuclearluse/nucleardata/toi/

- 11.Qaim SM. Decay data and production yields of some nonstandard positron emitters used in PET. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52:111–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jurisson SS, Lydon JD. Potential technetium small molecule radiopharmaceuticals. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2205–2218. doi: 10.1021/cr980435t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Edwards DS. 99mTc-labeled small peptides as diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2235–2268. doi: 10.1021/cr980436l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dilworth JR, Parrott SJ. The biomedical chemistry of technetium and rhenium. Chem Soc Rev. 1998;27:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller PW, Long NJ, Vilar R, Gee AD. Synthesis of 11C, 18F, 15O, and 13N radiolabels for positron emission tomography. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:8998–9033. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermanson GT Bioconjugate techniques. London: Academic Press, Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brechbiel MW. Bifunctional chelates for metal nuclides. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52:166–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holland JR, Aigbirhio Fl, Betts HM, et al. Functionalized bis(thiosemicarbazonato) complexes of zinc and copper: synthetic platforms toward site-specific radiopharmaceuticals. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:465–485. doi: 10.1021/ic0615628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S. Bifunctional coupling agents for radiolabeling of biomolecules and target-specific delivery of metallic radionuclides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1347–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson CJ, Green MA, Fujibayashi Y. Chemistry of copper radionuclides and radiopharmaceutical products. In: Welch MJ, Redvanly CS, editors. Handbook of radiopharmaceuticals: radiochemistry and applications. New York: Wiley; 2003. pp. 401–422. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson CJ, Welch MJ. Radiometal-labeled agents (non-technetium) for diagnostic imaging. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2219–2234. doi: 10.1021/cr980451q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volkert WA, Hoffman TJ. Therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2269–2292. doi: 10.1021/cr9804386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunphy MPS, Lewis JS. Radiopharmaceuticals in preclinical and clinical development for monitoring of therapy with PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:106S–121S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yano Y, Chu P, Budinger TF, et al. Rubidium-82 generators for imaging studies. J Nucl Med. 1977;18:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maecke HR, Andre JR. 68Ga-PET radiopharmacy: a generator-based alternative to 18F-radiopharmacy. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop. 2007;62:215–242. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-49527-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ehrhardt GJ, Welch MJ. A new germanium-68/gallium-68 generator. J Nucl Med. 1978;19:925–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhernosekov KR, Filosofov DV, Baum RR, et al. Processing of generator-produced 68Ga for medical application. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1741–1748. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathias CJ, Lewis MR, Reichert DE, et al. Preparation of 66Ga- and 68Ga-labeled Ga(III)-deferoxamine-folate as potential folate-receptor-targeted PET radiopharmaceuticals. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:725–731. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(03)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith-Jones PM, Stolz B, Bruns C, et al. Gallium-67/gallium-68-[DFO]-octreotide—a potential radiopharmaceutical for PET imaging of somatostatin receptor-positive tumors: synthesis and radiolabeling in vitro and preliminary in vivo studies. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:317–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith-Jones PM, Solit DB, Akhurst T, et al. Imaging the pharmacodynamics of HER2 degradation in response to Hsp90 inhibitors. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:701–706. doi: 10.1038/nbt968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoyer D, Lubbert H, Bruns C. Molecular pharmacology of somatostatin receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1994;350:441–453. doi: 10.1007/BF00173012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reubi JC. In-vitro identification of vasoactive-intestinal-peptide receptors in human tumors—implications for tumor imaging. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1846–1853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reubi JC, Kvols L, Krenning E, Lamberts SWJ. Distribution of somatostatin receptors in normal and tumor-tissue. Metab Clin Exp. 1990;39:78–81. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90217-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reubi JC, Schaer JC, Laissue JA, Waser B. Somatostatin receptors and their subtypes in human tumors and in peritumoral vessels. Metab Clin Exp. 1996;45:39–41. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reubi JC, Waser B, Schaer JC, Laissue JA. Somatostatin receptor sst1-sst5 expression in normal and neoplastic human tissues using receptor autoradiography with subtype-selective ligands. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:836–846. doi: 10.1007/s002590100541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabriel M, Decristoforo C, Kendler D, et al. 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotide PET in neuroendocrine tumors: comparison with somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and CT. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:508–518. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.035667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gabriel M, Oberauer A, Dobrozemsky G, et al. 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotide PET for assessing response to somatostatin-receptor-mediated radionuclide therapy. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1427–1434. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.053421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Putzer D, Gabriel M, Henninger B, et al. Bone metastases in patients with neuroendocrine tumor: 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotide PET in comparison to CT and bone scintigraphy. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1214–1221. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mustafa MG, West HIJ, O’Brien H, et al. Measurements and a direct-reaction plus Hauser-Feshbach analysis of 89Y(p,n)89Zr, 89Y(p,2n)88Zr, and 89Y(p,pn)88Y reactions up to 40 MeV. Phys Rev C. 1988;38:1624–1637. doi: 10.1103/physrevc.38.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Link JM, Krohn KA, Eary JF, et al. 89Zr for antibody labelling and positron tomography. J Labeled Compd Radiopharm. 1986;23:1296–1297. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zweit J, Downey S, Sharma HL. Production of no-carrier-added zirconium-89 for positron emission tomography. Appl Radiatlsot. 1991;42:199–201. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meijs WE, Herscheid JDM, Haisma HJ, et al. Production of highly pure no-carrier added 89Zr for the labelling of antibodies with a positron emitter. Appl Radiat Isot. 1994;45:1143–1147. [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeJesus OT, Nickles RJ. Production and purification of 89Zr, a potential PET antibody label. Appl Radiat Isot. 1990;41:789–790. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hohn A, Zimmermann K, Schaub E, et al. Production and separation of “non-standard” PET nuclides at a large cyclotron facility: the experiences at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52:145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holland JR, Sheh Y, Lewis JS. Standardized methods for the production of high specific-activity zirconium-89. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:729–739. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCarthy DW, Shefer RE, Klinkowstein RE, et al. Efficient production of high specific activity 64Cu using a biomedical cyclotron. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoo J, Tang L, Perkins Todd A, et al. Preparation of high specific activity 86Y using a small biomedical cyclotron. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:891–897. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qaim SM. Production of high purity 94mTc for positron emission tomography studies. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:323–328. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Firouzbakht ML, Schlyer DJ, Finn RD, et al. Iodine-124 production: excitation function for the 124Te(d,2n)124I and l24Te(d,3n)123I reactions from 7 to 24 MeV. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res Sect B. 1993;B79:909–910. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boswell CA, Brechbiel MW. Development of radioimmuno-therapeutic and diagnostic antibodies: an inside-out view. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34:757–758. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Philpott GW, Schwarz SW, Anderson CJ, et al. Radioimmuno PET: detection of colorectal carcinoma with positron-emitting copper-64-labeled monoclonal antibody. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1818–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perk LR, Visser OJ, Stigter-van Walsum M, et al. Preparation and evaluation of 89Zr-Zevalin for monitoring of 90Y-Zevalin biodistribution with positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1337–1345. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borjesson PKE, Jauw YWS, Boellaard R, et al. Performance of immuno-positron emission tomography with zirconium-89-labeled chimeric monoclonal antibody U36 in the detection of lymph node metastases in head and neck cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2133–2140. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Divgi CR, Pandit-Taskar N, Jungbluth AA, et al. Preoperative characterisation of clear-cell renal carcinoma using iodine-124-labelled antibody chimeric G250 (124I-cG250) and PET in patients with renal masses: a phase I trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:304–310. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70044-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Philpott GW, Siegel BA, Schwarz SW, et al. Immunoscintigraphy with a new indium-111-labeled monoclonal antibody (MAb 1A3) in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:782–792. doi: 10.1007/BF02050143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Connett JM, Anderson CJ, Guo LW, et al. Radioimmuno-therapy with a 64Cu-labeled monoclonal antibody: a comparison with 67Cu. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6814–6818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu AM, Senter PP. Arming antibodies: prospects and challenges for immunoconjugates. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1137–1146. doi: 10.1038/nbt1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verel I, Visser GWM, Boellaard R, et al. 89Zr immuno-PET comprehensive procedures for the production of 89Zr-labeled monoclonal antibodies. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1271–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meijs WE, Haisma HJ, Klok RR, et al. Zirconium-labeled monoclonal antibodies and their distribution in tumor-bearing nude mice. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meijs WE, Haisma HJ, Van der Schors R, et al. A facile method for the labeling of proteins with zirconium isotopes. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:439–448. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(96)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meijs WE, Herscheid JDM, Haisma HJ, Pinedo HM. Evaluation of desferal as a bifunctional chelating agent for labeling antibodies with Zr-89. Appl Radiat Isot. 1992;43:1443–1447. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(92)90170-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perk LR, Visser GWM, Budde M, et al. Facile radiolabeling of monoclonal antibodies and other proteins with zirconium-89 or gallium-68 for PET imaging using p-isothiocya-natobenzyl-desferrioxamine. Nat Protoc. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harper PV, Beck R, Charleston D, Lathrop KA. Mo/Tc generator. Nucleonics. 1964;22:1137. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lewis JS, Laforest R, Buettner TL, et al. Copper-64-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone): an agent for radiotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U SA. 2001;98:1206–1211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lewis JS, Lewis MR, Cutler PD, et al. Radiotherapy and dosimetry of 64Cu-TETA-Tyr3-octreotate in a somatostatin receptor-positive, tumor-bearing rat model. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3608–3616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Obata A, Kasamatsu S, Lewis JS, et al. Basic characterization of 64Cu-ATSM as a radiotherapy agent. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. [accessed October 1, 2009]; http://wwwclinicaltrialsgov/

- 68.McDevitt MR, Finn RD, Sgouros G, et al. An 225Ac/213Bi generator system for therapeutic clinical applications: construction and operation. Appl Radiat Isot. 1999;50:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(98)00151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McDevitt MR, Ma D, Simon J, et al. Design and synthesis of 225Ac radioimmunopharmaceuticals. Appl Radiat Isot. 2002;57:841–847. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(02)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scheinberg D, Ma D, McDevitt M, Borchardt R, inventors. Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, assignee. US patent 6683162. Targeted alpha particle therapy using actinium-225 conjugates. 2001 Sep 14;

- 71.Zalutsky MR. Targeted {alpha}-particle therapy of microscopic disease: providing a further rationale for clinical investigation. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1238–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Macklis RM, Kinsey BM, Kassis Al, et al. Radioimmuno-therapy with alpha-particle-emitting immunoconjugates. Science. 1988;240:1024–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.2897133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McDevitt MR, Ma D, Lai LT, et al. Tumor therapy with targeted atomic nanogenerators. Science. 2001;294:1537–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.1064126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang M, Yao Z, Zhang Z, et al. The anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody 7G7/B6, armed with the {alpha}-emitter 211At, provides effective radioimmunotherapy for a murine model of leukemia. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8227–8232. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huneke RB, Pippin CG, Squire RA, et al. Effective {alpha}-particle-mediated radioimmunotherapy of murine leukemia. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5818–5820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lucignani G. Alpha-particle radioimmunotherapy with astatine-211 and bismuth-213. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1729–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0856-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Madsen MT, Anderson JA, Halama JR, et al. AAPM Task Group 108: PET and PET/CT shielding requirements. Med Phys. 2006;33:4–15. doi: 10.1118/1.2135911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shleien BS, Iaback LA, Jr, Birky BK. Handbook of health physics and radiological health. 3rd. Baltimore (MD): Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buck A, Nguyen N, Burger C, et al. Quantitative evaluation of manganese-52m as a myocardial perfusion tracer in pigs using positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med. 1996;23:1619–1627. doi: 10.1007/BF01249625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matsumoto K, Fujibayashi Y, Konishi J, Yokoyama A. Radiolabeling and biodistribution of 62Cu-dithiocarbamate—an application for the new 62Zn/62Cu generator. Radioisotopes. 1990;39:482–486. doi: 10.3769/radioisotopes.39.11_482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cheng W-L, Wang Y-M, Cheng T-H, Tsai Y-M. Research and development of copper-62 radiopharmaceuticals. Nucl Sci J. 1997;34:276–290. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haynes NG, Lacy JL, Nayak N, et al. Performance of a 62Zn/62Cu generator in clinical trials of PET perfusion agent 62Cu-PTSM. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yagi M, Kondo K. A copper-62 generator. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1979;30:569–570. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Horlock PL, Clark JC, Goodier IW, et al. The preparation of a rubidium-82 radionuclide generator. J Radioanal Chem. 1981;64:263–271. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beyer GJ, Roesch F, Ravn HL. Strontium-82/rubidium-82 generator of high purity. Dresden (Germany): European Organization for Nuclear Research; 1990. Report No.: CERN-EP/90–91. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cackette MR, Ruth TJ, Vincent JS. Strontium-82 production from metallic rubidium targets and development of a rubidium-82 generator system. Appl Radiat Isot. 1993;44:917–922. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bilewicz A, Bartos B, Misiak R, Petelenz B. Separation of 82Sr from rubidium target for preparation of 82Sr/82Rb generator. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 2006;268:485–487. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tarkanyi F, Szelecsenyi F, Kopecky R, et al. Cross sections of proton induced nuclear reactions on enriched 111Cd and 112Cd for the production of 111In for use in nuclear medicine. Appl Radiat Isot. 1994;45:239–239. doi: 10.1016/0969-8043(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Roesch F, Qaim SM, Novgorodov AF, Tsai Y-M. Production of positron-emitting 110mIn via the 110Cd(3He,3n)110Sn -> 110mIn process. Appl Radiat Isot. 1996;48:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lundqvist H, Scott-Robson S, Einarsson L, Malmborg P. Tin-110/indium-110—a new generator system for positron emission tomography. Appl Radiat Isot. 1991;42:447–450. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(91)90104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miller DA, Sun S, Yi JH. Preparation of a tellurium-118/anti-mony-118 radionuclide generator. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 1992;160:467–476. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Downs D, Miller DA. Radiochemical separation of antimony and tellurium in isotope production and in radionuclide generators. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 2004;262:241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Richards R, Ku TH. The xenon-122-iodine-122 system: a generator for the 3.62-min positron emitter, iodine-122. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1979;30:250–254. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lagunas-Solar MC, Carvacho OF, Harris LJ, Mathis CA. Cyclotron production of xenon-122(20.1 h) -> iodine-122 (beta + 77%; EC 23%; 3.6 min) for positron emission tomography Current methods and potential developments. Appl Radiat Isot. 1986;37:835–842. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mathis CA, Lagunas-Solar MC, Sargent T, 3rd, et al. A122Xe-122I generator for remote radio-iodinations. Int J Rad Appl Instrum A. 1986;37:258–260. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(86)90183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tarkanyi F, Qaim SM, Stoecklin G, et al. Nuclear reaction cross sections relevant to the production of the xenon-122-> iodine-122 system using highly enriched xenon-124 and a medium-sized cyclotron. Appl Radiat Isot. 1991;42:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Abrams DN, Knaus EE, Wiebe LI, et al. Production of chlorine-34m from a gaseous hydrogen sulfide target. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1984;35:1045–1048. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lagunas-Solar MC, Carvacho OF, Cima RR. Cyclotron production of PET radionuclides: 34mCI (33.99 min; beta + 53%; IT 47%) with protons on natural isotopic chlorine-containing targets. Appl Radiat Isot. 1992;43:1375–1381. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lambrecht RM, Wolf AR. The cyclotron production of potassium-38, manganese-51 and −52m, and krypton-77 for positron emission tomography. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 1979;16:129–130. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tarkanyi F, Kovacs Z, Qaim SM, Stoecklin G. Production of potassium-38 via the 38Ar(p,n)-process at a small cyclotron. Appl Radiat Isot. 1992;43:503–507. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ishiwata K, Ido T, Monma M, et al. Potential radiopharmaceuticals labeled with titanium-45. Appl Radiat Isot. 1991;42:707–712. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(91)90173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vavere AL, Laforest R, Welch MJ. Production, processing and small animal PET imaging of titanium-45. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vavere AL, Welch MJ. Preparation, biodistribution, and small animal PET of 45Ti-transferrin. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Klein ATJ, Rosch F, Qaim SM. Investigation of 50Cr(d,n)51Mn and natCr(p,x)51Mn processes with respect to the production of the positron emitter 51Mn. Radiochim Acta. 2000;88:253–264. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Watanabe S, Ishioka NS, Osa A, et al. Production of the positron emitters 52Mn and 62Zn for application to plant study. Japan: Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Akiha F. Excitation curves and thick target yield curves of iron-52, iron-55, manganese-56, chromium-49, chromium-51, and vanadium-48 formed by bombardment of alpha-particles on natural chromium. Nippon Kagaku Kaishi. 1972:1664–1669. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Akiha F, Aburai T, Nozaki T, Murakami Y. Yield of iron-52 for the reactions of helium-3 and alpha-particles with chromium. Radiochim Acta. 1972;18:108–111. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Akiha F, Aburai T, Nozaki T, Murakami Y. Production of iron-52 for medical use by cyclotron bombardment. Radioisotopes. 1972;21:155–159. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ku TH, Richards R, Stang LG, Jr, Prach T. Preparation of 52Fe and its use in a 52Fe/52mMn generator. Radiology. 1979;132:475–477. doi: 10.1148/132.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Silvester DJ, Sugden J. Production of carrier-free 52Fe for medical use. Nature. 1966;210:1282–1283. doi: 10.1038/2101282a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dahl JR, Tilbury RS. Use of a compact, multiparticle cyclotron for the production of iron-52, gallium-67, indium-111 and iodine-123 for medical purposes. Int J Appl Radiat Isotop. 1972;23:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0020-708x(72)90110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Koyama-Ito H, Ito A, Kashiwa Y, et al. A trial to produce iron-52 for medical use by cyclotron bombardment. Radioisotopes. 1991;40:118–121. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Smith-Jones R, Schwarzbach R, Weinreich R. The production of iron-52 by means of a medium-energy proton accelerator. Radiochim Acta. 1990;50:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Goethals R, Volkaert A, Vandewielle C, et al. 55Co-EDTA for renal imaging using positron emission tomography (PET): a feasibility study. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:7–81. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zaman MR, Qaim SM. Excitation functions of (d,n) and (d,alpha) reactions on 54Fe: relevance to the production of high purity 55Co at a small cyclotron. Radiochim Acta. 1996;75:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lagunas-Solar MC, Jungerman JA, Hall JN. Cyclotron production of carrier-free cobalt-55 A potential label for bleomycin. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 1977;13:184. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Neirinckx RD. Cyclotron production of nickel-57 and cobalt-55 and synthesis of their bleomycin complexes. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1977;28:561–562. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lagunas-Solar MC, Jungerman JA. Cyclotron production of carrier-free cobalt-55, a new positron-emitting label for bleomycin. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1979;30:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 119.McCarthy DW, Bass LA, Cutler PD, et al. High purity production and potential applications of copper-60 and copper-61. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26:351–358. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(98)00113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Szelecsenyi F, Kovacs Z, Suzuki K, et al. Formation of 60Cu and 61Cu via Co + 3He reactions up to 70 MeV: production possibility of 60Cu for PET studies. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res Sect B. 2004;222:364–370. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Szelecsenyi F, Blessing G, Qaim SM. Excitation functions of proton induced nuclear reactions on enriched nickel-61 and nickel-64: possibility of production of no-carrier-added copper-61 and copper-64 at a small cyclotron. Appl Radiat Isot. 1993;44:575–580. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Szelecsenyi F, Steyn GF, Kovacs Z, et al. Comments on the feasibility of 61Cu production by proton irradiation of natZn on a medical cyclotron. Appl Radiat Isot. 2006;64:789–791. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Obata A, Kasamatsu S, McCarthy DW, et al. Production of therapeutic quantities of 64Cu using a 12 MeV cyclotron. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:535–539. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(03)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Goethals R, Coene M, Siegers G, et al. Cyclotron production of carrier-free 66Ga as a positron emitting label of albumin colloids for clinical use. Eur J Nucl Med. 1988;14:152–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00293540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Szelecsenyi F, Tarkanyi F, Kovacs Z, et al. Production of 66Ga and 67Ga at a compact cyclotron. Acta Radiol Suppl. 1991;376:62–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lewis MR, Reichert DE, Laforest R, et al. Production and purification of gallium-66 for preparation of tumor-targeting radiopharmaceuticals. Nucl Med Biol. 2002;29:701–706. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sabet M, Rowshanfarzad P, Jalilian AR, et al. Production and quality control of 66Ga radionuclide. Nukleonika. 2006;51:147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kiss GG, Gyurky G, Elekes Z, et al. 70Ge(p,gamma)71As and 76Ge(p,n)76As cross sections for the astrophysical p process: sensitivity of the optical proton potential at low energies. Phys Rev C Nucl Phys. 2007;707:055801–055809. [Google Scholar]