ABSTRACT

Purpose: To describe the development of an educational programme for physiotherapists in the Netherlands, two toolkits of measurement instruments, and the evaluation of an implementation strategy. Method: The study used a controlled pre- and post-measurement design. A tailored educational programme for the use of outcome measures was developed that consisted of four training sessions and two toolkits of measurement instruments. Of 366 invited physiotherapists, 265 followed the educational programme (response rate 72.4%), and 235 randomly chosen control physiotherapists did not (28% response rate). The outcomes measured were participants' general attitude toward measurement instruments, their ability to choose measurement instruments, their use of measurement instruments, the applicability of the educational programme, and the changes in physiotherapy practice achieved as a result of the programme. Results: Consistent (not occasional) use of measurement instruments increased from 26% to 41% in the intervention group; in the control group, use remained almost the same (45% vs 48%). Difficulty in choosing an appropriate measurement instrument decreased from 3.5 to 2.7 on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Finally, 91% of respondents found the educational programme useful, and 82% reported that it changed their physiotherapy practice. Conclusions: The educational programme and toolkits were useful and had a positive effect on physiotherapists' ability to choose among many possible outcome measures.

Key Words: education, medical; outcome measures

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Décrire l'élaboration d'un programme de formation pour des physiothérapeutes aux Pays-Bas, deux trousses d'instruments de mesure et l'évaluation d'une stratégie de mise en œuvre. Méthode : L'étude a utilisé un concept de mesure contrôlé de type avant-après. Un programme de formation personnalisé pour l'utilisation des mesures de résultats a été élaboré; il consistait en quatre séances de formation et deux trousses d'instruments de mesure. Des 366 physiothérapeutes invités, 265 ont suivi le programme de formation (taux de réponse de 72,4 %), en plus de 235 physiothérapeutes témoins sélectionnés de façon aléatoire qui ne l'ont pas fait (taux de réponse de 28 %). Les résultats mesurés étaient l'attitude générale des participants envers les instruments de mesure, leur capacité de choisir des instruments de mesure, leur utilisation des instruments, l'applicabilité du programme de formation et les changements entraînés dans la pratique de la physiothérapie grâce au programme. Résultats : L'utilisation constante (non occasionnelle) des instruments de mesure a augmenté de 26 % à 41 % dans le groupe d'intervention; dans le groupe témoin, l'utilisation est restée presque la même (45 % par rapport à 48 %). La difficulté de choisir un instrument de mesure approprié a diminué de 3,5 à 2,7 sur échelle Likert à 5 points. Finalement, 91 % des répondants ont trouvé le programme de formation utile et 82 % ont indiqué que ce programme a changé leur pratique de la physiothérapie. Conclusions : Le programme de formation et les trousses se sont avérés utiles et ont eu un effet positif sur la capacité des physiothérapeutes à faire un choix parmi les nombreuses possibilités de mesure de résultats.

Mots clés : évaluation des résultats, mesure des résultats, mise en œuvre, physiothérapie

Since 1993, the Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap Fysiotherapie, or KNGF) has used specific guidelines as a standard for physiotherapy interventions. In 2012, 18 such guidelines were published, 14 of which have already been translated into English.1 All have the goal of increasing evidence-based practice among Dutch physiotherapists. An evidence-based approach is important to achieving optimal quality and uniform standards for physiotherapy interventions. In addition to describing the most suitable treatment according to the latest evidence, the KNGF guidelines recommend using various outcome measures to determine objectively whether a treatment has produced the desired outcome.2 The use of accepted outcome measures is important for both physiotherapists and their clients.

Although there has been some research on methods of implementing clinical practice guidelines in health care,2 until recently there were few studies on the implementation of outcome measures in physiotherapy clinical practice.3–7 Abrams and colleagues'8 study found that implementation of outcome measures was significantly improved by an active implementation approach consisting of lectures, educational seminars, peer contact, and online publications. This active approach is an important element of any implementation strategy, because relatively passive approaches (e.g., sending information) are unlikely to change practitioners' behaviour.9–11

Both Jette and colleagues3 and Van Peppen and colleagues12 investigated the actual use of the outcome measures recommended by the guidelines; they found that only 48% and 52% of respondents, respectively, were using outcome measures consistently in their practice. These findings indicate a real need for a more active approach to implementing the use of measurement instruments.3,12 In the Netherlands, implementation of outcome measures in general took a relatively passive approach until 2008, when the KNGF, having made active implementation of outcome measures a key aspect of its quality policy in 2007, launched its Measurement in Clinical Practice project in cooperation with two research centres in the Netherlands. This project targeted physiotherapists in private practice and those working in nursing homes, two groups that differ in several ways: In addition to treating dissimilar populations, and therefore needing different measurement instruments, they operate within different organizational infrastructures (e.g., nursing homes are characterized by a more hierarchical management policy) and are compensated in different ways (nursing homes employ physiotherapists who are paid a salary, and private practitioners' income depends on their productivity). The project group adopted Grol and Wensing's5,13 model of systematic implementation, which emphasizes that a thorough analysis of improvement goals and of the current situation in the intended setting is essential for successful implementation and advises targeting strategies to specific barriers to and facilitators of the desired change.

Therefore, the first phase of the project, described in an earlier article,14 documented the current use of outcome measures, barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of outcome measures, and proposed strategies to improve the use of outcome measures. The barriers were classified into four categories: (1) physiotherapist factors (competence and attitude; e.g., lack of knowledge); (2) organizational factors (practice and colleagues; e.g., lack of time); (3) patient and client factors (e.g., patients unaccustomed to the use of questionnaires); and (4) measurement instrument factors (e.g., instruments that are too long).14 The most important facilitators identified in this study were physiotherapists' positive attitude toward outcome measures and conviction of the benefits of their use; the most important barriers identified were physiotherapists' lack of competence in using the instruments in the process of clinical reasoning, perceived problems in changing behaviour, limitations at the level of practice organization (no room, no time), and unavailability of outcome measures.14 Strategies for overcoming barriers to implementation were chosen on the basis of these findings and on the implementation literature. The proposed strategy focused on (1) an educational programme tailored specifically to implementing outcome measures into clinical reasoning and organizational structures (practice) and (2) a toolkit of short and easily applicable instruments and user descriptions.14

The purpose of this article is, first, to describe the development of the tailored educational programme and the toolkit and, second, to describe the initial effects of the combined synergetic application of both the programme and the toolkit on physiotherapists' attitudes toward and use of outcome measures in their daily practice.

Method

We studied the effects of the tailored educational programme we developed and used a controlled pre- and post-measurement design study with a follow-up 8 months after the first measurement.

Recruitment

We invited members of the KNGF who were working in private practices or working in nursing homes to participate in the educational programme. A total of 366 physiotherapists registered voluntarily to attend the programme. We divided them into 23 groups of approximately 16 each, and they acted as the intervention group. This group was invited to complete an online survey before the course began.

We also sent 1,000 invitations to complete the same survey to a random sample of the 15,785 KNGF members; those who responded constituted the control group for the study. To ensure that none of these 1,000 physiotherapists had attended the educational programme, we later checked the list against the course registration lists.

Development of educational programme and toolkits

On the basis of the most frequently mentioned barriers and literature, we developed two toolkits: one consisted of measurement instruments intended for physiotherapists working in private practice, and the other was geared toward physiotherapists working in nursing homes. Our intention was to restrict each toolkit to a maximum of 10–20 measurement instruments, which should be appropriate for 70%–80% of clients seen from day to day, because one problem identified in our earlier study was physiotherapists' inability to select the most appropriate instrument from the large number of outcome measures available. We formulated criteria related to feasibility (e.g., short, easy to administer, easy to understand), quality (e.g., reliability, validity, responsiveness), and support (acceptability) for both clinicians and clients.12 The instruments were, on the basis of the criteria mentioned, selected by consensus in the project group.

In addition to the toolkits, we developed an educational programme to enhance the use of outcome measures in general and of those included in the toolkits specifically. The programme was tailored on the basis of the questionnaire completed by participants at first measurement, which addressed three factors: (1) readiness to change, (2) policy regarding (use of) measuring in practice, and (3) use of instruments.7 The programme's purpose was to minimize barriers at the level of the physiotherapist (i.e., those relating to physiotherapists' competence or attitude).

The programme consisted of four interactive half-day training sessions spread over 4–5 months. Between sessions, participants were instructed to use the measurement instruments in the toolkit with patients in their clinical practice; coaching and feedback were provided during the four training sessions. In each session, participants discussed the instruments in the toolkit; their use in daily practice for diagnostic, prognostic, or evaluative purposes; and the interpretation of test results in relation to their own patients and in the process of clinical reasoning. In addition, physiotherapists were taught how to overcome organizational barriers in their own practice settings (e.g., by sending out questionnaires in advance or using special software).

Programme instructors were drawn from all physiotherapy educational programmes in the Netherlands and were trained as part of their ongoing professional development to teach the modules within their local networks. These instructors received mandatory training over 2 days from the project group. Every university participated and taught the programme in its catchment area, ensuring good geographical coverage within the Netherlands.

Procedure and evaluation

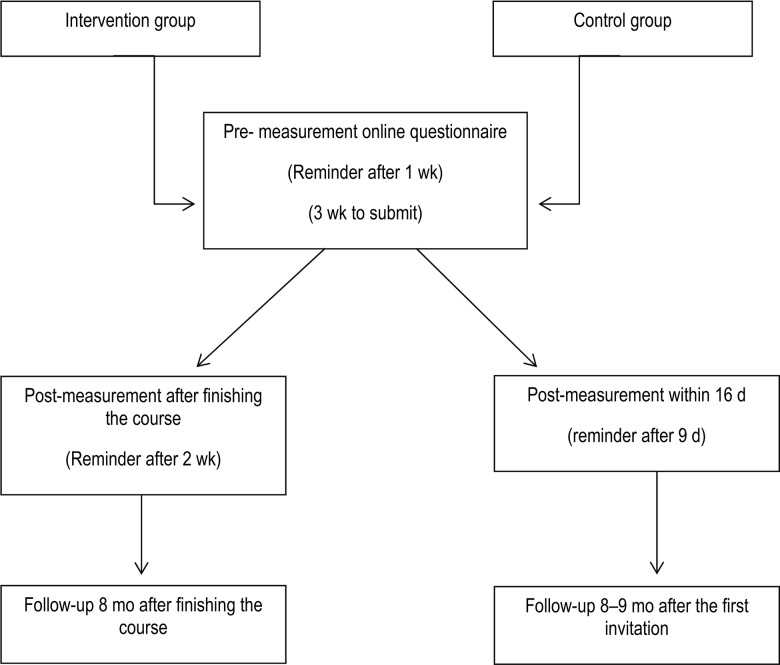

Data were collected via online surveys. The surveys were managed by the Institute for Applied Sciences (ITS) and the Strategy and Development unit of the KNGF. All physiotherapists received a reminder to complete the survey 1 week after the link for the pre-measurement survey was sent; the deadline for submitting a completed questionnaire was 3 weeks after receiving the link to the survey. Participants in the intervention group received an invitation to complete the post-measurement survey immediately after finishing the course and a reminder 2 weeks after finishing the educational programme. Follow-up time for the intervention group was 8 months after finishing the course (third survey). Participants in the control group were invited to complete the post-measurement survey within a period of 16 days after enrolling in the study and were sent a reminder on day 9. Follow-up time for the control group was 8–9 months after enrollment (third survey).

Outcome measures

Outcome variables were collected via online surveys. The first two outcome variables for the study—(1) physiotherapists' general attitude toward measurement instruments and (2) their ability to choose measurement instruments—were measured using a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1=strongly agree, indicating positive attitude and knowledge, to 5=strongly disagree, indicating negative attitude and lack of knowledge). The third outcome variable, participants' use of measurement instruments, was determined by asking participants to estimate with what percentage of their clients they used measurement instruments (none of every five patients [0%], one of every five patients [20%], two of every five patients [40%], three of every five patients [60%], four of every five patients [80%], or five of every five patients [100%]). Participants in the intervention group were asked about the applicability of the tailored educational programme and changes achieved in physical therapy practice; the data were quantified in terms of the percentage of respondents who agreed and disagreed with survey items relating to these outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by the ITS and the KNGF's Strategy and Development unit, using PASW Statistics for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago). The characteristics of the intervention and control groups were documented using descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistics and paired t-tests were used to test within-group differences between pre-measurement and post-measurement; to test differences between intervention and control groups at baseline, we used Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and independent-samples t-tests for the other variables. We also used univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to test pre–post differences between the intervention and control groups (between-groups analysis), controlling for the possible effect of certain covariates on the variables of interest between pre-measurement and post-measurement. To evaluate the possibility of selective non-response at posttesting, we used unpaired t-tests to compare the pre- and post-measurement groups in terms of gender, age, work setting, working hours, work experience, attitude toward outcome measures, and readiness to change behaviour. For all applied statistical tests, a p-value of 0.05 was used as a cutoff point for the 95% CI.

Figure 1.

Timelines for data collection and reminders for both groups.

Ethics approval was not required for this study because no patients were involved.

Results

Development of the toolkits resulted in a toolkit for private practitioners consisting of 19 measurement instruments and a toolkit for nursing homes containing 14 instruments (see Appendix 1).

In the intervention group (n=366), response rates were 72% (265/366) at pre-measurement and 67% (247/366) at post-measurement; 175 participants (48%) completed both measurements. For the control group, response rates were 28% (279/1,000) at pre-measurement and 19% (190/1,000) at post-measurement; 86 (9%) completed both measurements. Reasons for non-response are not known. After removing from the analysis 13 respondents in the intervention group and 44 in the control group who provided no information relevant to any of our research questions, we were left with a sample size of 252 in the intervention group and 235 in the control group at pre-measurement. An additional 18 respondents in the intervention group and 36 in the control group did not answer the questions pertaining to gender, setting, age, work week, work experience, and attitude towards outcome measures.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of respondents in the intervention and control groups. The intervention group was older and worked more hours per week than the control group. The majority of respondents in both groups reported a positive attitude toward outcome measures; the proportion was higher in the intervention group, but the difference was not statistically significant. The intervention group reported significantly more difficulty in changing behaviour and more difficulty in choosing the appropriate measurement instrument. The intervention group also reported that they were less likely to use outcome measures consistently and were more likely to consistently not use them (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Pre-Measurement Characteristics of Participants

| No. (%) of respondents* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Intervention group (n=234)* |

Control group (n=199)* |

p-value† |

| Sex | 0.21 | ||

| Male | 116 (49.6) | 87 (43.7) | |

| Female | 118 (50.4) | 113 (56.3) | |

| Employment setting | 0.64 | ||

| Primary care | 186 (79.5) | 154 (77.4) | |

| Nursing home | 48 (20.5) | 45 (22.6) | |

| Age, y | <0.001 | ||

| <30 | 35 (15.0) | 47 (23.6) | |

| 30–50 | 98 (41.9) | 107 (53.8) | |

| ≥50 | 101 (43.1) | 46 (22.6) | |

| Working week, h/wk | 0.008 | ||

| <25 | 48 (20.5) | 66 (33.2) | |

| 25–33 | 72 (30.8) | 45 (22.6) | |

| ≥33 | 114 (48.7) | 88 (44.2) | |

| Work experience, y | 0.002 | ||

| 0–10 | 42 (17.9) | 64 (32.2) | |

| 11–20 | 40 (17.1) | 38 (19.1) | |

| 21–30 | 88 (37.6) | 60 (30.1) | |

| ≥30 | 64 (27.3) | 37 (18.6) | |

| Attitudes and behaviours (intervention group, n=252; control n=235) | |||

| Positive attitude toward outcome measures | 0.79 | ||

| Agree | 221 (87.7) | 202 (86.0) | |

| Neutral | 24 (9.5) | 24 (10.2) | |

| Disagree | 7 (2.8) | 9 (3.8) | |

| Difficulty in changing behaviour | 0.036 | ||

| Agree | 134 (53.2) | 98 (41.7) | |

| Neutral | 51 (20.2) | 55 (23.4) | |

| Disagree | 67 (26.6) | 82 (34.9) | |

| Use of measurement instruments, % of clients | |||

| Consistently use | 26 | 41 | <0.001 |

| Occasionally use | 25 | 25 | 0.95 |

| Consistently do not use | 48 | 34 | <0.001 |

| Difficulty in choosing among the many available measurement instruments‡ | 3.5 | 3.1 | <0.001 |

Unless otherwise indicated.

p-values for testing differences between intervention and control groups. For categorical variables, Fisher's exact test was used; for the last four variables, independent-samples t-test was used.

Mean score on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree).

Comparing the pre- and post-measurement groups in terms of gender, age, work setting, work hours, working experience, attitude toward outcome measures, and difficulty in changing behaviour indicated that there was no selective non-response between pre- and post-measurement.

After completing the educational programme, the intervention group scores were significantly more positive on all aspects of the post-measurement survey, and the control group showed no change. ANCOVA found no significant effect of age, gender, or work experience on the use of measurement instruments (test of between-subjects effect for work experience, F3,236=0.563, p=0.64).

Table 2 reports pre- and post-measurement results for both intervention and control groups on the use of outcome measures and the ability to choose the right outcome measures for clients. These within-group results are based on paired t-tests; we also analyzed the effects of work experience, gender, and age as covariates in the between-groups ANCOVA, which found no significant influence of work experience, gender, or age on the results.

Table 2.

Use of and Ability to Choose Outcome Measures

| Intervention group (n=175) |

Control group (n=86) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Pre | Post | 95% CI for difference* |

p-value | Pre | Post | 95% CI for difference* |

p-value |

| Consistent use of measurement instruments, % of clients | 26 | 41 | 11–20 | 0.001† | 45 | 44 | −3 to 8 | 0.40 |

| Consistent non-use of measurement instruments, % of clients | 50 | 31 | −24 to −13 | 0.001† | 30 | 28 | −7 to 4 | 0.59 |

| Difficulty in choosing one of many possible measurement instruments‡ | 3.48 | 2.71 | −0.93 to −0.61 | 0.001† | 2.93 | 2.87 | −0.28 to 0.14 | 0.53 |

Calculated as posttest−pretest.

Significant at p<0.05.

Mean score on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree).

Table 3 summarizes responses from the intervention group to questions about the applicability of the tailored educational programme. These questions were designed to evaluate the usefulness of the programme and the way in which it did or did not change the group's physiotherapy practice.

Table 3.

Applicability of the Educational Programme and Changes in Physiotherapy Practice

| Question | No. (%) of respondents |

|---|---|

| Was the content of the educational programme useful? | |

| Yes | 164 (91) |

| No | 17 (9) |

| Did you change your physiotherapy management? | |

| Yes | 149 (82) |

| No, because I already work according to the methods presented | 18 (10) |

| No, because I have no patients to whom I could apply an outcome measure | 4 (2) |

| No, because I obtain good results without using outcome measures | 10 (6) |

Discussion

Our aim in this study was to describe the development of a tailored educational programme and two toolkits of feasible outcome measures and to evaluate their effects on the overall implementation of outcome measures in the daily practice of physiotherapists.

The educational programme and the toolkits were developed on the basis of a systematic analysis of barriers to and facilitators of the use of measurement instruments in daily practice14 and were pre-measured in practice with physiotherapists working in private practice (78%) and in nursing homes (22%). This distribution is somewhat different from that in the Netherlands, in which 13,355 physiotherapists work in private practice and fewer than 1,000 work in 962 nursing homes. It is, however, possible that those who responded were physiotherapists more interested in outcome measures than those who did not respond.

Our study found facilitators and barriers similar to those reported in other studies:3,12,14,15 In general, participants had a positive attitude toward outcome measures (a facilitator), but the majority admitted to difficulties in changing their behaviour (a barrier). At baseline, there were significant differences in work experience and age between the intervention group and the control group; these two variables are obviously related to each other, but neither influenced the increased use of measurement instruments after the intervention. The control group rated themselves as better able to choose measures and as using the measures more often; our control respondents may represent a group of early adopters who already feel confident in the use of measurement instruments, whereas the intervention group may have felt a greater need for additional education on the use of measurement instruments. Although the intervention group rated themselves as less able to choose measures and as using the measures less often than the control group at baseline, the educational programme succeeded in bringing them up to a significantly higher level. In fact, one may call both the intervention and the control groups early adapters with regard to their attitude toward measurement instruments. However, the intervention group, possibly recognizing their lack of knowledge, were more eager to learn, whereas the control group indicated they were already familiar with the use of measurement instruments.

One of our strategies was to focus on developing toolkits of short and easily applicable instruments and user descriptions. We anticipated that it would be feasible to develop these toolkits and provide therapists with ready-to-use instruments that were easy to incorporate into their clinical reasoning process. We realize that the toolkits are not fixed sets, and the choice of instruments remains open to discussion. However, because therapists find it almost impossible to choose from the overwhelming number of instruments available to them—for example, the KNGF's 18 published guidelines recommend a total of 127 measurement instruments—there was a need to provide guidance in the selection and application of these instruments.

Overall, the observed effect of the intervention was a significant increase in the consistent use of outcome measures (from 26% at baseline to 41% at follow-up; p=0.001) and a substantial decrease in the consistent non-use of measurement instruments (from 50% at baseline to 31% at follow-up; p=0.001). Neither variable changed significantly in the control group. Similarly, we found a substantial decrease in mean reported difficulty in choosing a measurement instrument among the intervention group (from 3.5 of 5 at baseline to 2.7 of 5 at follow-up), whereas the control group showed no significant change. However, the control group scored higher on these outcomes.

After completing the educational programme, 91% of respondents in the intervention group reported finding its content useful during their daily work as physiotherapists, and 82% reported having changed their physiotherapy practice with respect to outcome measurement. Only 9% of respondents who attended the programme and had not previously used outcome measures did not change their physiotherapy practice after completing the programme. Thus, participants clearly experienced the toolkit and educational programme as useful, and the great majority changed their attitude toward using measurement instruments in daily practice.

Nevertheless, this study has significant limitations. First, the study used a non-randomized sample, and therefore the data may be subject to selection bias, because the intervention group consisted of physiotherapists who voluntarily participated in the tailored educational programme and were eager to learn and the control group likely consisted of early adopters confident enough in their use of measurement instruments to voluntarily complete the online questionnaire. The intervention group also received information about the educational programme in advance, which may have influenced them to subscribe to the programme; however, study participants' perception that they were less informed about outcome measures, as evidenced by their having more difficulty in choosing the appropriate measurement instruments and greater non-use of outcome measures, may have led them to enrol in the course.

We expected the control group to be poorly informed about measurement instruments because they got no information at all regarding the content of the educational programme. However, the baseline measurement did not confirm this expectation. At follow-up, these between-groups differences disappeared, suggesting an intervention effect. A delayed-start control group (consisting of half of the therapists who volunteer for the intervention, who are first measured over a period of no intervention to serve as a control) might have been useful in determining the effects of the intervention.

Second, although using an online questionnaire allowed us to survey a large group of physiotherapists, we were not able to ask more in-depth questions. Furthermore, the questionnaire's reliability (reproducibility) was not investigated before the study, and therefore we cannot rule out detection or measurement bias, although both groups were measured in an identical way.

Third, response rates for both intervention and control groups were low; the possible influence of the low response rates is not known, but it could seriously jeopardize the validity of this study.

Finally, our study did not include a long-term follow-up component, and therefore we do not know to what degree physiotherapists who attended the tailored educational programme continued their change in physiotherapy practice. More studies are needed to determine the long-term outcomes of this intervention.

Conclusion

Developing toolkits and a tailored educational programme based on a thorough problem analysis proved feasible and showed a positive effect on physiotherapists' ability to choose one of many possible outcome measures and on their use of outcome measures in daily physiotherapy practice.

On the basis of our findings, we recommend that physiotherapy associations invest in developing toolkits and tailored educational programmes to facilitate the implementation of their clinical practice guidelines. Further research is needed to confirm the results of this study in other groups and in a randomized controlled trial.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

In general, relatively few Dutch physiotherapists use outcome measures consistently in their practice. The barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of outcome measures, as well as proposed strategies to improve the use of outcome measures, are well understood.

What this study adds

This study found that physiotherapists' attitude toward the use of measurement instruments and their actual use of these instruments are enhanced by offering the combination of measurement instruments toolkits and an educational programme.

Appendix 1

Toolkit's Measurement Instruments

| Patient's demands | Patient Specific Complaints Questionnaire |

|---|---|

| For physiotherapists in private practices | |

| Impairments | |

| Pain | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) |

| Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) | |

| Range of motion | Goniometer |

| Muscle force | Handheld dynamometer |

| Activities of daily living | |

| Shoulder, arm, and hand | Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (DASH) |

| Shoulder | Shoulder Pain & Disability Index (SPADI) |

| Cervical | Neck Disability Index (NDI) |

| Lumbar | Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDQ) Acute Low Back Pain Screening Questionnaire (ALBPSQ) |

| Hip | Algofunctional index |

| Knee | Algofunctional index (degenerative disorders) |

| Lysholm score (traumatic patients) combined with Tegner score | |

| Ankle | Function score |

| Ottawa Ankle Rules | |

| Walking | 6-minute walk test |

| Personal factors | Four Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire (4DSQ) |

| Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia | |

| Self-Efficacy Scale | |

| General perceived effect |

Global Perceived Effect (7-point scale) |

| For physiotherapists in nursing homes | |

| Immobility and sitting | Trunk Control Test (TCT) |

| Mobility | |

| Staying | Berg Balance Scale (BBS) |

| Transfers | Timed up-and-go (TUG) |

| Walking | Elderly Mobility Scale (EMS) |

| Functional Ambulation Categories (FAC) | |

| 10-meter walking test | |

| 6-minute walking test | |

| Risk-to-fall analysis | STRATIFY risk assessment tool |

| Arm and hand function | Frenchay Arm Test (FAT) |

| Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) | |

| Handheld dynamometer | |

| Activities of daily living | Barthel Index |

| Pain | Numeric rating scale (NRS) |

References

- 1. Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy. KNGF evidence-based clinical practice guidelines [Internet]. Amersfoort (Netherlands): The Society; 2015. [cited 2014 Jan 15]. Available from: http://www.kngfrichtlijnen.nl/index.php/kngf-guidelines-in-english [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Wees PJ, Jamtvedt G, Rebbeck T, et al. Multifaceted strategies may increase implementation of physiotherapy clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54(4):233–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0004-9514(08)70002-3. Medline:19025503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jette DU, Halbert J, Iverson C, et al. Use of standardized outcome measures in physical therapist practice: perceptions and applications. Phys Ther. 2009;89(2):125–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20080234. Medline:19074618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ketelaar M, Russell DJ, Gorter JW. The challenge of moving evidence-based measures into clinical practice: lessons in knowledge translation. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2008;28(2):191–206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01942630802192610. Medline:18846897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rivard LM, Russell DJ, Roxborough L, et al. Promoting the use of measurement tools in practice: a mixed-methods study of the activities and experiences of physical therapist knowledge brokers. Phys Ther. 2010;90(11):1580–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20090408. Medline:20813819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Russell DJ, Rivard LM, Walter SD, et al. Using knowledge brokers to facilitate the uptake of pediatric measurement tools into clinical practice: a before-after intervention study. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):92 http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-92. Medline:21092283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stevens JG, Beurskens AJ. Implementation of measurement instruments in physical therapist practice: development of a tailored strategy. Phys Ther. 2010;90(6):953–61. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20090105. Medline:20413576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abrams D, Davidson M, Harrick J, et al. Monitoring the change: current trends in outcome measure usage in physiotherapy. Man Ther. 2006;11(1):46–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2005.02.003. Medline:15886046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):II2–45. Medline:11583120 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. Medline:14568747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kay T, Myers AM, Huijbregts M. How far have we come since 1992? A comparative survey of physiotherapist's use of outcome measures. Physiother Can. 2001;53:268–81 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Peppen RP, Maissan FJ, Van Genderen FR, et al. Outcome measures in physiotherapy management of patients with stroke: a survey into self-reported use, and barriers to and facilitators for use. Physiother Res Int. 2008;13(4):255–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pri.417. Medline:18972323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grol R, Wensing M. Effective implementation: A model In: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, editors. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. London: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Swinkels RA, van Peppen RP, Wittink H, et al. Current use and barriers and facilitators for implementation of standardised measures in physical therapy in the Netherlands. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12(1):106 http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-106. Medline:21600045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Copeland JM, Taylor WJ, Dean SG. Factors influencing the use of outcome measures for patients with low back pain: a survey of New Zealand physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1492–505. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20080083. Medline:18849478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]