Abstract

We previously reported a transgenic animal model of variant pigmentation based on epidermal expression of stem cell factor (SCF) and well-characterized coat color genes bred into the C57Bl/6 background. In this system, constitutive expression of SCF by epidermal keratinocytes results in the maintenance of epidermal melanocytes in the interfollicular basal epidermal layer and subsequent pigmentation of the epidermis itself. In this report, we describe extending this animal model by developing a compound mutant transgenic amelanotic animal defective at both the melanocortin 1 receptor (Mc1r) and tyrosinase (Tyr) loci. We have observed SCF-dependent pigment deposition in specific anatomic regions regardless of tyrosinase (Tyr) or Mc1r genetic status. Thus, in the presence of K14-Scf, tyrosinase-null animals (previously thought incapable of synthesizing melanin) exhibited progressive robust epidermal pigmentation with age in the ears and tails. Furthermore, in the presence of the K14-Scf transgene, Tyr-defective animals demonstrated tyrosinase activity, suggesting that the c2j Tyr promoter defect is leaky and that Tyr expression can be rescued in part by SCF in the ears and tail. Lastly, we found that UV sensitivity of K14-Scf congenic animals differing only at the Mc1r or Tyr loci depended mainly on the amount of eumelanin present in the skin. These findings suggest that c-kit signaling can overcome the c2j Tyr promoter mutation in the ears and tails of aging animals but that UV resistance depends on accumulation of epidermal eumelanin.

Keywords: melanocyte, pigmentation, melanin, UV radiation, erythema

Introduction

Mouse models of human epidermal diseases have been limited by the fact that, unlike human skin, melanocytes are not present at the murine dermal-epidermal junction. Indeed, murine dorsal skin is devoid of melanocytes except for follicular melanocytes present in the dermis where they impart pigment to the fur. However, because epidermal pigmentation depends on melanin production by interfollicular epidermal melanocytes and accumulation of pigment in the keratinocyte layers, the dorsal skin of mice is unpigmented, even in strains such as C57Bl/6 with darkly pigmented fur. We previously reported an animal model of “humanized skin” of defined epidermal pigmentation, wherein constitutive secretion of stem cell factor (SCF) by epidermal keratinocytes resulted in the retention of large numbers of melanocytes in the interfollicular epidermal basal layer (Kunisada et al., 1998, D'Orazio et al., 2006), mimicking their epidermal localization in human skin. In this transgenic model, constitutive epidermal production of SCF does not seem to affect the melanin type produced by the melanocytes. Rather, the type and quantity of melanin produced by interfollicular epidermal melanocytes parallels that of the follicular melanocytes, determined by classic pigment-determining loci such as tyrosinase (Tyr), the rate-limiting synthetic enzyme required for production all types of melanins, or the melanocortin 1 receptor (Mc1r) which encodes the melanocytic Gs-coupled cell surface receptor on melanocytes that binds to melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH) and mediates growth and differentiation signals via cAMP second messenger production.

Roughly a decade ago, Kunisada and others described the phenotype of the K14-Scf transgenic murine strain wherein stem cell factor (SCF), the ligand for the receptor tyrosine kinase c-kit, is constitutively produced by epidermal keratinocytes. As a consequence of epidermal SCF production, melanocytes were maintained in the interfollicular epidermis and imparted pigmentation to the skin itself through melanin production and transfer to keratinocytes (Kunisada et al., 1998).

Using this model system, pheomelanotic and amelanotic mice were generated by introducing mutations in either Mc1r (Robbins et al., 1993) or Tyr (Le Fur et al., 1996) in otherwise congenic C57BL/6 mice. As in human skin, epidermal pigments in this animal model consisted of varying amounts of eumelanin, the darkly-colored potent UV-blocking pigment found naturally in dark-skinned individuals, and pheomelanin, a red/blonde sulfated pigment found as the dominant melanin species in the skin of UV-sensitive individuals of fair complexion. Thus, K14-Scf C57BL/6 animals with intact Tyr and Mc1r genes were found to produce abundant eumelanin in the skin and were resistant to acute and chronic UV-induced skin damage. In contrast, K14-Scf animals defective at the Mc1r locus instead produced abundant pheomelanin in the skin and albino animals lacking tyrosinase produced neither type of melanin pigment and were amelanotic (D'Orazio et al., 2006). Because pigmentation depended on the function of Mc1r and Tyr rather than the presence of stem cell factor, we concluded production of the specific melanin species in these mice was independent of c-Kit (SCF receptor) signaling. Since that original report, we have observed these animals over time and have noticed interesting pigmentation phenotypes as animals aged. Specifically, K14-Scf transgenic animals harboring either the Mc1re/e or Tyrc2j/c2j skin lightening mutations developed progressive epidermal darkening in the ear and tail skin over time. In this report, we describe the compound mutant Mc1re/e Tyrc2j/c2j C57Bl/6 K14-Scf animal and show that “albino” animals defective at the Tyr locus (previously thought to be incapable of making melanin) demonstrate progressive and robust darkening of the ears and tail through tyrosinase-mediated melanin production in the presence of the K14-Scf transgene. We hypothesize the c2j Tyr loss-of-function promoter mutation, classically thought to result in total loss of expression of the tyrosinase gene, can be overcome by c-Kit-mediated signaling. These data also suggest that c-kit signals are biochemically distinct from Mc1r signaling and cannot rescue eumelanin synthesis in the presence of a defective Mc1r.

Results

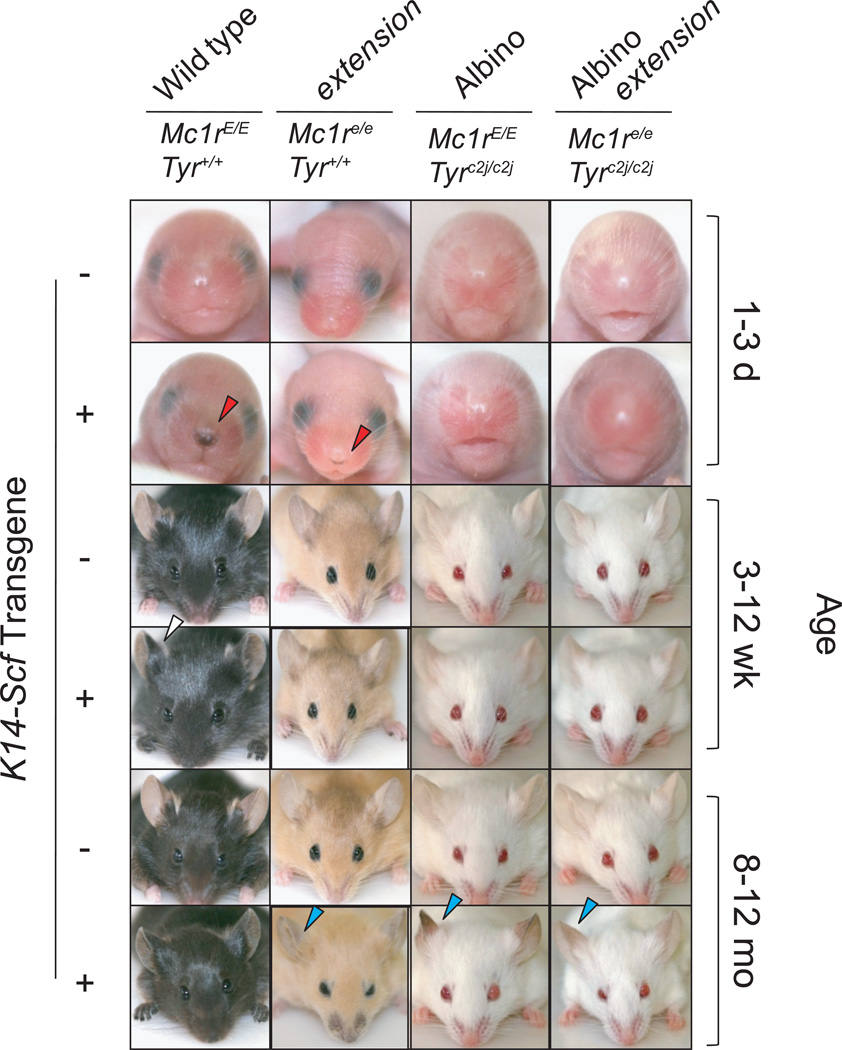

K14-Scf transgenic C57BL/6 animals (Kunisada et al., 1998) were crossed with known C57BL/6 coat color variants to generate amelanotic or pheomelanotic fair-skinned K14-Scf animals as previously described (D'Orazio et al., 2006). The presence of the K14-Scf transgene did not rescue pigmentation differences caused by either the defective Mc1r or Tyr genes, as fair-skinned and albino animals harboring the K14-Scf transgene displayed a similar pigmentation phenotype to their non-transgenic counterparts (Fig. 1). Thus, tyrosinase-null animals appeared amelanotic despite the presence of the K14-Scf transgene, and Mc1r defective animals appeared pheomelanotic regardless of the K14-Scf transgene. Whereas little difference was noted in fur color between K14-Scf transgenic and non-transgenic animals, we observed marked differences in skin color. The effect was most notable in the wild type (Mc1rE/E, Tyr+/+) background, with non-transgenic animals exhibiting little pigmentation of the skin, and K14-Scf transgenic animals having jet-black skin throughout the epidermis (Fig. 1, 2). The original murine model included wild type (Mc1rE/E, Tyr+/+), extension (Mc1re/e, Tyr+/+) and albino (Mc1rE/E, Tyrc2j/c2j) strains, and therefore was unable to distinguish Mc1r-mediated responses independent of pigment effects. Specifically, in tyrosinase-intact strains, loss of Mc1r function caused almost complete cessation of eumelanin production in favor of pheomelanin production. If pheomelanin contributes to UV-mediated damage as others have suggested (Hill and Hill, 2000, Ye and Simon, 2003, Takeuchi et al., 2004, Samokhvalov et al., 2005), then the presence of pheomelanin might confound assessment of other Mc1r-mediated cutaneous responses. Thus, in order to distinguish pigment-independent aspects of Mc1r function, we generated a K14-Scf transgenic animal system defective at both the Mc1r and Tyr loci (Fig. 1). We now report pigmentation differences between these strains of mice.

Fig. 1. Epidermal pigmentation of C57BL/6 mice variant for the Mc1r and Tyr loci and the K14-Scf transgene: facial characteristics.

Animals are otherwise congenic on the C57Bl/6 genetic background. Each photo is a representative image of the particular strain at the specified age. Note the differences in epidermal pigmentation (as can be seen by the skin over the ears and paws) between K14-Scf transgenic and non-transgenic animals are most notable after 1 month of age. The presence of the K14-Scf transgene can be assessed visually in pigmented (i.e., tyrosinase-functional) strains by dark nose spots from day of life 1 (red arrows). K14-Scf animals with wild type pigmentation demonstrate darkly pigmented epidermis (white arrows), and K14-Scf mice of all coat colors develop progressive pigmentation of the ears by 8–12 months of age.

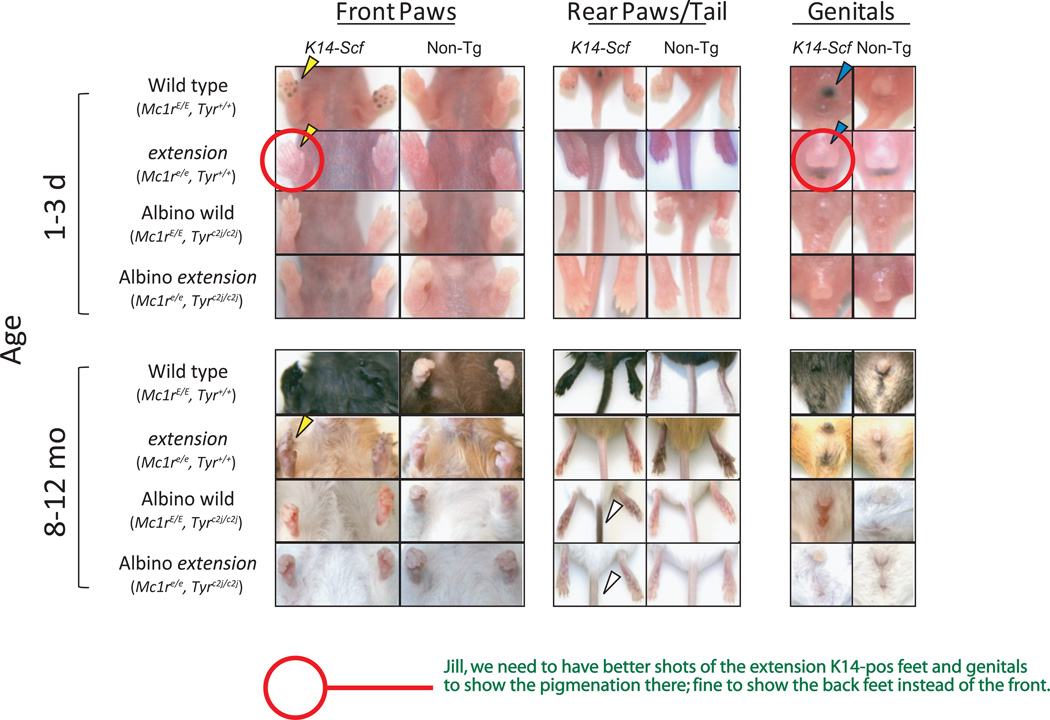

Fig. 2. Epidermal pigmentation of C57BL/6 mice variant for the Mc1r and Tyr loci and the K14-Scf transgene: extremities, tail and genitalia.

Representative images of animals of the indicated genotype and age are shown. In K14-Scf animals that have functional tyrosinase, there is increased deposition of melanin in the paw pads (yellow arrows) and genitals (blue arrows) that can be seen as early as days 1–3 of life and persists over time. In albino (Tyrc2j/c2j) animals, K14-Scf-mediated melanin deposition in the tail and paws is readily visualized in older animals (white arrows). Note that epidermal pigmentation is weaker in the setting of a dysfunctional Mc1re/e as compared to wild type Mc1rE/E, regardless of Tyr status (comparing extension animals to wild type animals and albino wild to albino extension animals).

Upon close inspection of the Mc1r-defective extension mouse, we noticed that, despite an overall reversal of pigmentation from a eumelanotic complexion to a pheomelanotic complexion in the coat and skin, there were discreet and reproducible anatomic sites of hyperpigmentation present in these animals from birth. Specifically, the K14-Scf extension animals could be discriminated from their non-transgenic counterparts by black spots at the entrance to the nares (Fig 1, red triangles), foot pads (Fig. 2, yellow triangles), and genitalia (Fig. 2, blue triangles). In the pheomelanotic animals, these hyperpigmented areas persisted throughout life, facilitating differentiation of the K14-Scf animals from their non-transgenic counterparts. Notably, the same discreet areas of hyperpigmentation were noted in very young K14-Scf wild type animals (Fig. 2), but gradually the distinction between these sites and the rest of the epidermis was lost due to the generalized deposition of eumelanin in the epidermis that occurred in the first to second week of life.

When we compared albino (Tyrc2j/c2j) animals with an intact Mc1r and albino animals with a defective Mc1r, we noticed that the skin of the ears and tails of animals darkened in both strains over time despite the fact that these animals should be incapable of producing melanin due to the c2j promoter mutation (Fig. 1). This epidermal darkening was limited to albino animals harboring the K14-Scf transgene, and was never observed in K14-Scf negative animals. Although the ear and tail skin of both Mc1r-intact and Mc1r-defective K14-Scf albino animals darkened over time, there seemed to be a marked difference in the nature of the pigmentation between the two groups. Specifically, the ears and tails of K14-Scf albino wild type animals actually blackened over time, whereas the ears and tails of K14-Scf albino extension animals became more pigmented in reddish/brown hues with age (Fig. 1). In albino wild type K14-Scf animals, pigmentation of the ears and tail skin first became apparent at roughly 3 weeks of life, displayed progressive darkening over the next several months, and became maximally and intensely dark at roughly 8–12 months of life (Fig. 1). These observations suggested to us that c-Kit signaling in melanocytes could rescue tyrosinase expression in the setting of the inactivating c2j promoter mutation.

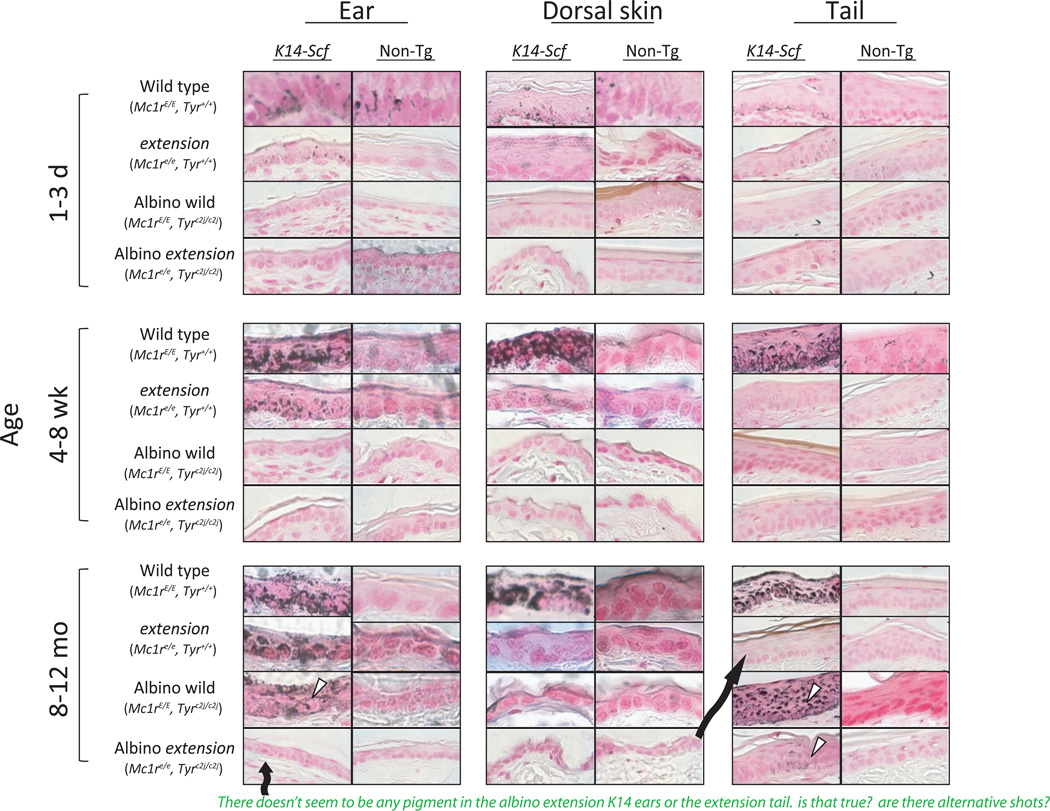

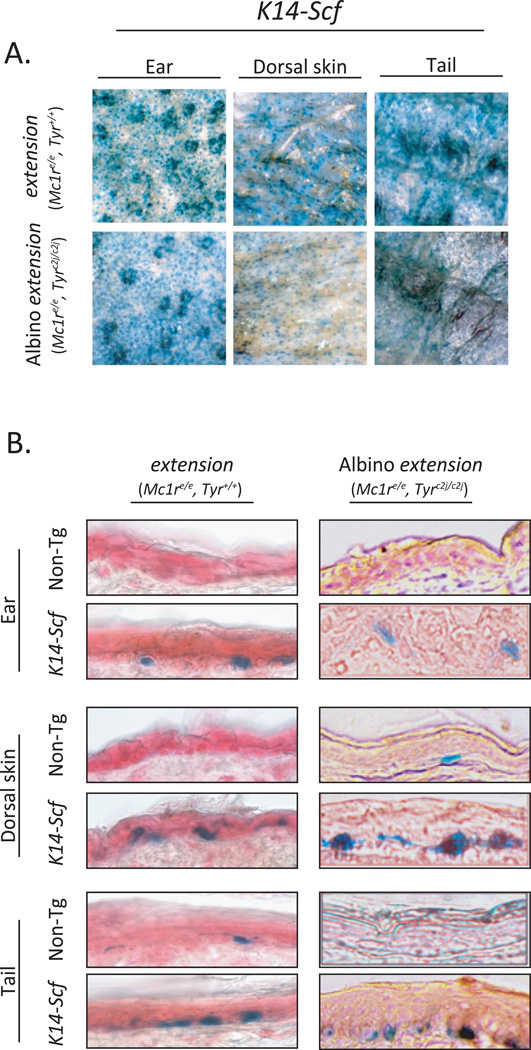

To determine whether skin darkening was due to melanin deposition, sections of the skin from different anatomic sites from each of the four murine strains were stained for melanin using the Fontana-Masson method (Zappi and Lombardo, 1984). Wild type K14-Scf transgenic animals, which are the most heavily pigmented animals among the four groups, revealed abundant epidermal melanin throughout the epidermis (Fig. 3). In contrast, fair-skinned extension K14-Scf animals exhibited reduced melanin staining, and Tyr-defective animals had negligible levels of either melanin subtype in their dorsal skin regardless of Mc1r status. In contrast, when skin sections from the ears and tails of albino K14-Scf animals were stained for melanin by the Fontana-Masson method, we found clear evidence of melanin deposition in these anatomic sites as animals aged. Melanin staining was much more intense in the ears and tails of aged albino K14-Scf animals with a wild type Mc1r when compared to their Mc1r-defective counterparts (Fig. 3), suggesting that the nature of the melanin deposited may be different between the two strains (i.e., accumulation of pheomelanin in the ears and tail of Mc1r-defective strains, and deposition of eumelanin when Mc1r is functional).

Fig. 3. K14-Scf-induced skin darkening is due to melanin deposition.

Skin biopsies were harvested from animals of the specified age and from the indicated anatomic location and were stained using the Fontana–Masson procedure wherein melanin pigments appear black in section. Representative images at 400× magnification are shown. Note much more robust melanin staining in the presence of the K14-Scf transgene than in the non-transgenic state and evidence for melanin staining in the ear and tail of K14-Scf albino animals as they age (white arrows).

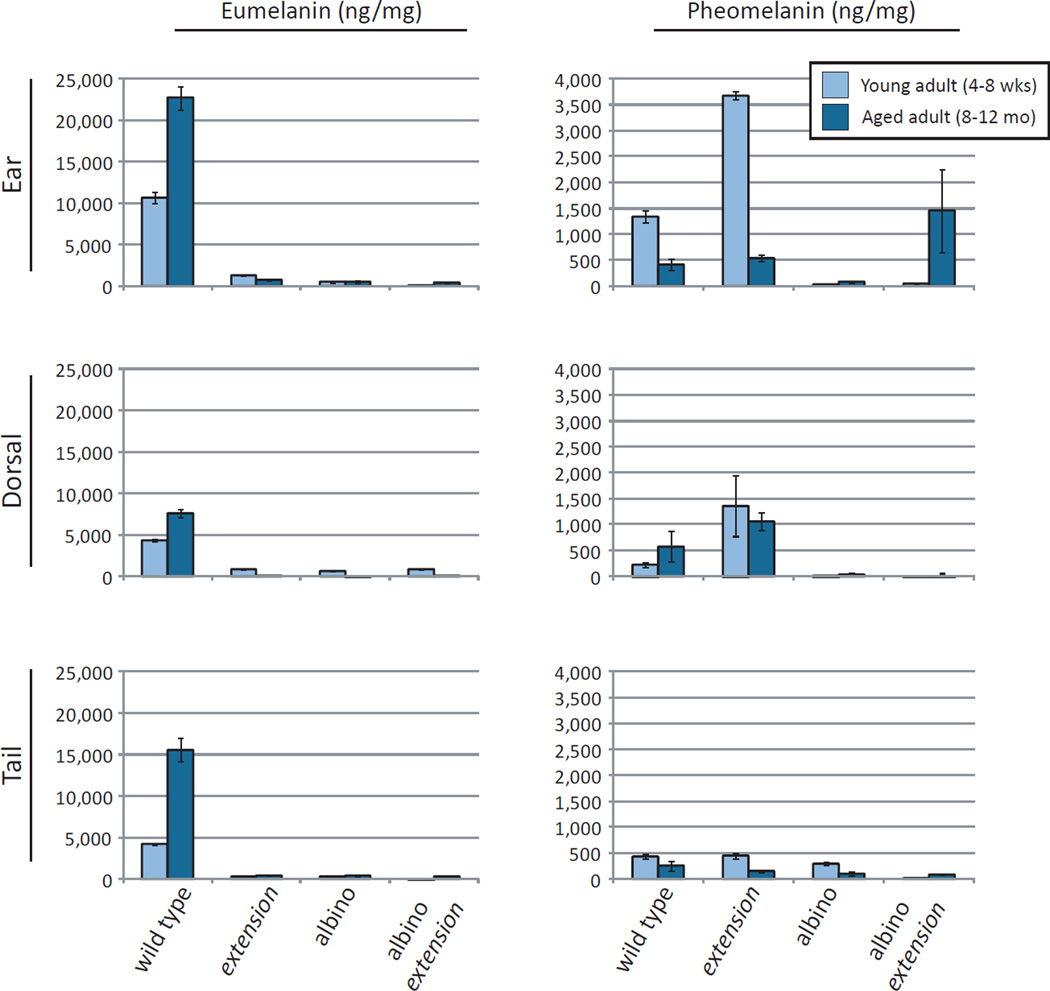

To test this hypothesis, we directly measured melanin type in the skin of the animals, determining the levels of eumelanin and pheomelanin in depilated ear, nose, and tail via HPLC analysis (Ito, 1993). As expected, we saw abundant eumelanin in the skin of the ears, dorsum and tail in wild type (Mc1rE/E, Tyr+/+) K14-Scf transgenic animals, with scant eumelanin in either Mc1R-defective or Tyr-defective strains (Fig. 4). Further, extension (Mc1re/e, Tyr+/+) animals demonstrated accumulation of pheomelanin in the skin, with the highest levels in the ears. Unlike the age-dependent eumelanin deposition observed in wild type strains, higher levels of pheomelanin were observed in young adult animals when compared with their older counterparts (Fig. 4). Though the skin of the ears and tails of albino (Mc1rE/E, Tyrc2j/c2j) K14-Scf ears/tail clearly demonstrated age-dependent pigmentation both visually (Fig. 1) and by Fontana-Masson melanin staining (Fig. 3), however, we found little mature eumelanin in these biopsies (Fig. 4). In contrast, there was accumulation of pheomelanin in the ears of albino extension (Mc1re/e, Tyrc2j/c2j) K14-Scf animals (Fig. 4). Overall, we conclude that melanin pigments are manufactured in discreet anatomic locations in mice harboring both the Tyr c2j promoter mutation and K14-Scf transgene, and that the nature of the pigment produced is dependent on the level of Mc1r function.

Fig. 4. Quantification of eumelanin and pheomelanin in whole depillated skin of the indicated anatomic location of K14-Scf animals of the specified genotype.

K14-Scf transgenic albinos, albino extensions, extensions, and wild type animals were biopsied from the ear, tail, or doral tissue. Young adult (4–8 wks; light bars) or older adult (8–12 mo; dark bars) were compared. Levels of pheomelanin and eumelanin were quantified by HPLC as described (Wakamatsu and Ito, 2002). Data shown represent the mean of three animals per condition +/− SEM is shown.

We also investigated the possibility that the loss of tyrosinase affected melanocyte viability in the skin, utilizing the DCT-LacZ transgene incorporated into our system (Mackenzie et al., 1997) to stain skin sections of extension and albino extension animals for interfollicular epidermal melanocytes. Although melanocytes clearly differed in their ability to produce melanin pigments, neither the inactivating extension Mc1r mutation nor the inactivating c2j Tyr promoter mutation affected melanocyte viability, as evidenced by abundant the melanocytes in the epidermis of both the extension and albino extension animals (Fig. 5A). Their presence in the interfollicular epidermis was, however, dependent on the K14-Scf transgene (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. K14-Scf-mediated epidermal melanocytosis is unaffected by defective Mc1r or Tyr status.

A) Interfollicular epidermal melanocytes are present in abundance in the ears, dorsal skin and tail of 4–8 week old C57Bl/6 animals harboring both the K14-Scf and the dopachrome tautomerase-β-galactosidase (DCT-LacZ) gene (Mackenzie et al., 1997) as shown in these whole skin en face images (magnification 20X). B) the K14-Scf transgene promotes retention of melanocytes in the interfollicular stratum basale as shown in these representative skin sections from young adult animals of the indicated genotype. Please note that by virtue of β-galactosidase expression restricted to cells of melanocytic lineage, melanocytes stain blue in these images (magnification 400 ×).

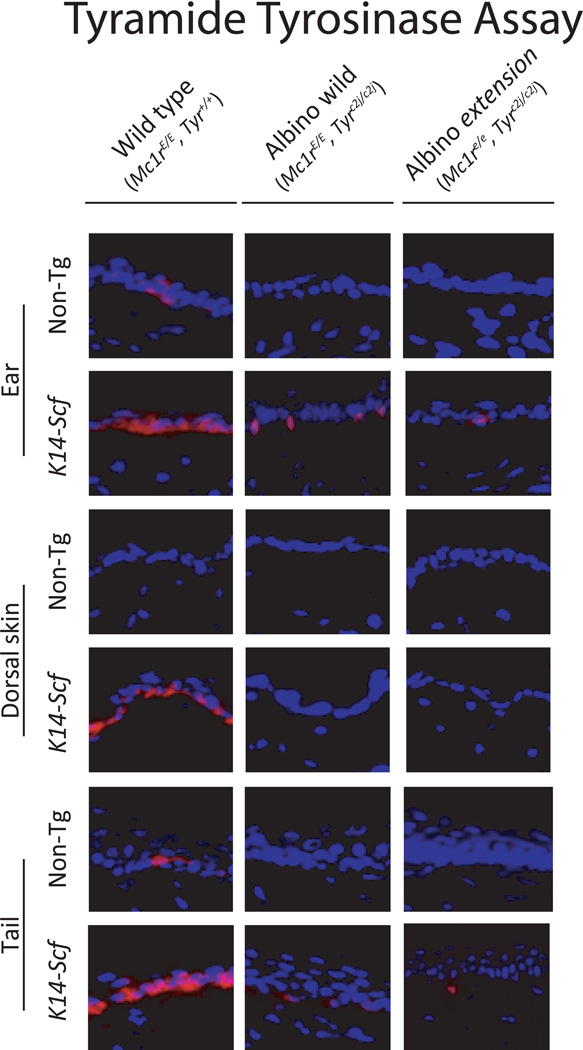

In order to clarify whether tyrosinase activity is responsible for the pigment production seen in the ears and tail of K14-Scf albino and albino extension animals as they aged, we assessed the skin for tyrosinase activity using the tyramide-based tyrosinase assay (TTA) (Han et al., 2002). The TTA is an in situ test for tyrosinase activity that is based on tyrosinase-mediated deposition of biotin, which can be easily detected with a fluorescent dye conjugated to streptavidin; in order to yield a fluorescent signal, cells must express functionally active tyrosinase. Though the most robust TTA responses were clearly found among biopsies from fully pigmented wild type (Mc1rE/E, Tyr+/+) K14-Scf strains, we found evidence of age-dependent tyrosinase activity in the epidermis of ears and tails (but not dorsal skin) of K14-Scf albino animals regardless of Mc1R function (Fig. 6). There was no evidence for tyrosinase activity in biopsies from non-transgenic animals, regardless of Mc1R or Tyr status, again demonstrating the requirement for the K14-Scf transgene to support functional melanocytes in the interfollicular epidermis. From these observations, we conclude that the c2j promoter mutation of the Tyr gene can be rescued by c-Kit signaling, and, since there was tyrosinase present in both the albino wild type and the albino extension K14-Scf animals, we further conclude that loss of Mc1r function does not inhibit tyrosinase expression or enzymatic activity.

Fig. 6. K14-Scf transgene-dependent tyrosinase activity in the ears and tail of Tyrc2j/c2j animals.

Representative images (400 × magnification) of skin biopsies harvested from the indicated anatomic location from C57Bl/6 animals of the specified genotype. In the tyramide tyrosinase assay, deposition of fluorescence (pink color) is dependent on functional tyrosinase activity (Han et al., 2002). Skin sections are counterstained with DAPI to illustrate epidermal/dermal architecture. Note evidence for tyrosinase activity (pink staining in melanocytes) in the epidermal-dermal junction in ears and tail of K14-Scf strains harboring the Tyrc2j/c2j mutation.

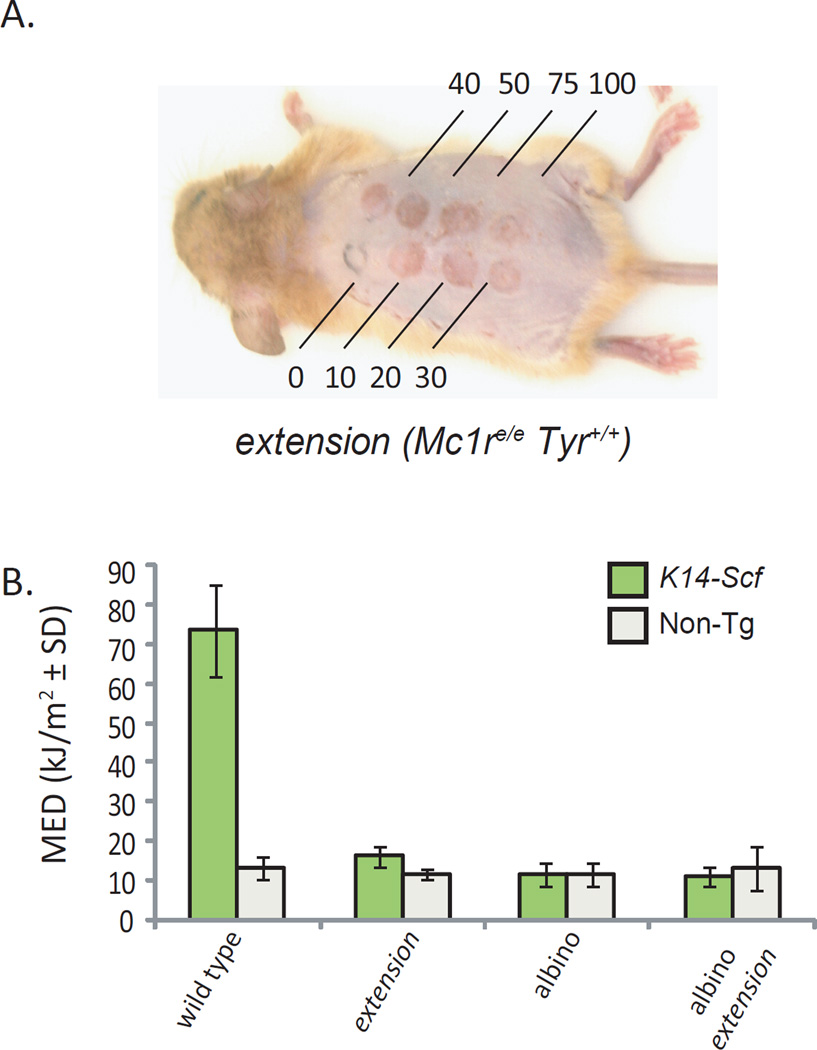

Lastly, we tested the UV sensitivity of our K14-Scf strains in order to determine the extent to which Mc1r and Tyr independently affect UV sensitivity in our animal model of humanized skin. We exposed cohorts of K14-Scf and non-transgenic Mc1r-intact and Mc1r-mutant animals to UV radiation, and determined the minimal dose of UV radiation that caused inflammation of the skin. The degree of photoprotection directly correlated with the degree of eumelanin in the skin prior to UV exposure (Fig. 7). Thus, wild type (Mc1rE/E, Tyr+/+) K14-Scf animals with their eumelanin-laden epidermis were much more resistant to UV-induced inflammation than any other pigment variant. The contribution of epidermal melanocytes (and their pigment) to UV protection is clearly demonstrated by the fact that wild type (Mc1rE/E, Tyr+/+) non-transgenic animals (who lack epidermal melanin (Fig. 3) exhibited similar UV sensitivity as amelanotic or pheomelanotic strains. Although the K14-Scf extension mice have pheomelanin in their skin and the albino animals have neither eumelanin nor pheomelanin, we found no appreciable difference in the UV sensitivity (as measured by minimal edematous dose or MED) between the extension and albino strains, indicating pheomelanin is a very poor blocker of UV photons (Fig 7). Since albino (Mc1rE/E, Tyrc2j/c2j) and albino extension (Mc1re/e, Tyrc2j/c2j) K14-Scf strains displayed similar UV sensitivities (Fig. 7), pigment-independent Mc1r effects seemed to have little contribution to UV-induced cutaneous inflammation in our model. Overall, we conclude that Mc1r protects against UV-mediated inflammation mainly by promoting eumelanin deposition in the setting of functional pigment synthesis.

Fig. 7. UV resistance correlates with the degree of eumelanotic pigmentation.

Minimal erythematous dose of UV radiation was used to estimate UV sensitivity in K14-Scf or non-transgenic C57Bl/6 animals of the indicated genotype. MED, determined 24 h after exposure to various doses of UV, was calculated as the minimal dose of UV per animal that caused erythema or edema of the entire circle of exposed skin for the given dose. (A) representative image of a UV-exposed extension animal 24 h post-irradiation (with doses in kJ /m2 indicated). (B) Average MED ± SEM of each strain is depicted. Note that a higher MED value indicates a higher dose of UV needed to cause inflammation and correlates with UV resistance.

Discussion

The K14-Scf transgenic murine model is a useful model in which to study melanocyte responses in the epidermis. Because of constitutive production of SCF by keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis in this model, melanocytes are recruited to the interfollicular epidermis, just as they are positioned in normal human skin. In this manner, melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis produce melanin, and transfer the pigment to adjacent keratinocytes in the epidermis, imparting color to the skin of K14-Scf mice and facilitating studies of UV responses in skin of variant melanin composition in an otherwise congenic system. Although melanocytes are generally absent from the interfollicular epidermis of non-transgenic animals, they can be found in scant numbers in the ears and tail (Rosdahl, 1979). Interestingly, these are the same anatomic locations in which we observed rescue of dark pigmentation in extension and albino K14-Scf mice, suggesting that there is a pigmentation signal distinct from the MSH-Mc1r axis in these sites. Although the factor(s) that promotes darkening in the ears and tail remain to be elucidated, our data indicate melanin synthesis is not dependent on the Mc1r/cAMP axis, as the ears and tails of the K14-Scf animals darken in the presence and absence of Mc1r function. Importantly, in the genetic setting of a tyrosinase deficiency as occurs from the c2j Tyr promoter mutation (Le Fur et al., 1996), the function of Mc1r still controls the type of melanin produced in the ears and tail, much as is the case with coat color in the non-transgenic or tyrosinase-intact states. Thus, we found deposition of pheomelanin in the ears of K14-Scf albinos with mutant Mc1r. Intriguingly, while Fontana-Masson staining (Fig. 3) indicated melanin deposition in the ears of the albino K14-Scf animals, HPLC analysis revealed little eumelanin accumulation at all. Further investigations must be done to clarify these discrepancies, however it may be possible that the melanin deposited in the ears of albino K14-Scf animals as they age may be a precursor species of eumelanin unrecognized by HPLC analysis but that promotes dark pigmentation nonetheless. If true, this might suggest a novel, c-kit-mediated, role for tyrosinase in later steps of eumelanin maturation. In any case, the presence of SCF in the basal layer of the epidermis not only recruited more melanocytes in the skin, but also promoted tyrosinase activity, as judged by the TTA assay (Fig. 6).

Despite the presence of melanocytes in the basal layer of the dorsal skin of the K14-Scf albino animals, we did not observe age-related darkening in the dorsal skin, regardless of Mc1r status. Only melanocytes found in the ears and tail produced epidermal melanin with age (Figs. 1,2). Thus we conclude that there must be additional factor(s) in the skin of the ears and the tail that promote tyrosinase expression/activity in addition to c-Kit signaling. Whether these are the same factor(s) that promote accumulation of interfollicular melanocytes in the absence of K14-Scf remains to be determined. However, since epidermal interfollicular melanocytes are present in the basal layer in each of the four animal strains studied herein, we conclude neither Mc1r nor tyrosinase function is requisite for de facto melanocyte survival.

We compared UV sensitivity of the four K14-Scf strains of animals by measuring the minimal erythematous dose (MED) of the dorsal skin in response to UV radiation (Mackenzie, 1983, Sayre et al., 1981). This tested the ability of eumelanin and pheomelanin to protect the skin against the sub-acute effects of UV, as measured by global inflammation (edema and/or erythema). Our data reveal that epidermal eumelanin is profoundly UV-protective whereas pheomelanin does little to prevent UV-induced inflammation. In fact, the UV sensitivity of the pheomelanotic skin was essentially identical to that of the amelanotic skin (Fig. 7). Due to the poor UV-protective properties of pheomelanin, we posit approaches that up-regulate eumelanin in the skin, for example by either MSH mimics (Abdel-Malek et al., 1995, Abdel-Malek et al., 2006) or by pharmacologic manipulation of cAMP signaling (D'Orazio et al., 2006), would likely result in enhanced cutaneous UV protection.

Overall, our data indicate that, at least in terms of MED, the UV sensitivity of fair-skinned Mc1r-defective skin occurs mainly because of lack of eumelanization rather than non-pigment Mc1r effects. Curiously, although interfollicular melanocytes are present in the skin of the dorsal trunk, ears and tail in the K14-Scf albino animals, we noted anatomic variation with respect to their ability to manufacture melanin pigments (ears > tail > dorsal skin). Therefore we conclude there may be unidentified factor(s) in the ears and tail that promotes melanocyte differentiation.. Since we found clear biochemical evidence of tyrosinase activity in epidermal skin of the ears and tails K14-Scf albino strains, our findings also suggest that SCF-c-Kit interaction rescues tyrosinase function in the setting of the c2j promoter mutation and raises possible novel therapeutic avenues to treat albinism caused by defective tyrosinase function.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6JJ mice of varying pigment phenotype were crossed with K14-Scf transgenic animals (also on the C57BL/6JJ backgrounds) as described previously (Kunisada et al., 1998, D'Orazio et al., 2006). The pigmentation phenotypes used were: C57BL/6JJ Mc1rE/E Tyr+/+ (wild type, black pigmentation), C57BL/6JJ Mc1re/e Tyr+/+ (extension mutant, blonde pigmentation), and C57BL/6JJ Mc1rE/E Tyrc2j/c2j (albino, non-pigmented). Presence of the K14-Scf transgene was assessed either by phenotype (by obvious skin color characteristics in the case of wild type or extension animals) or, in the albino animals, by PCR amplification of a fragment specific to the K14-Scf transgene (DNA obtained by tail snip), as described (Kunisada et al., 1998). Transgenic dopachrome tautomerase-β-galactosidase mice (Mackenzie et al., 1997) were obtained from Dr. Ian Jackson’s laboratory. All experiments were carried out in accordance with institutionally-approved animal protocols.

Melanin staining, β-galactosidase melanocyte quantification and the tyramide tyrosinase assay (TTA)

Animals were either killed by CO2 narcosis or anesthetized with isoflurane anesthesia prior to skin sampling. Approximately 1 cm2 skin biopsies were obtained from sheared skin using institutionally-approved protocols. For Fontana-Masson melanin staining, samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and were paraffin embedded and sectioned (6 microns) by the University of Kentucky histopathology core laboratory before being stained for melanin using the Fontana-Masson Staining Kit (American Master*Tech Scientific, Inc., Lodi, CA) (Zappi and Lombardo, 1984), which stains melanin black. For LacZ-mediated identification of melanocytes in DCT-LacZ transgenic animals and the TTA assay, frozen sections (6 microns) were prepared. β-galactosidase staining and counterstaining with nuclear fast red were performed as described (Mackenzie et al., 1997, Franco et al., 2001), and numbers of blue-stained cells were quantified. For in situ TTA-mediated determination of tyrosinase activity, frozen sections were treated with avidin/biotin blocking reagents (Vector Laboratory) and stained for tyrosinase using Perkin Elmer’s Tyramide Reagent Pack as described (Han et al., 2002). Microscopic evaluation of skin biopsies was performed using an Olympus BX51 microscope, and images were captured using the QCapture Pro program (QImaging Software). For whole mount β-gal stains, images were taken with a dissecting scope (Olympus SZ61) before sectioning.

Melanin quantification

Eumelanin and pheomelanin were quantitatively analyzed by HPLC based on the formation of pyrrole-2,3,5-tricarboxylic acid (PTCA) by permanganate oxidation of eumelanin and 4-amino-3-hydroxyphenylalanine (4-AHP) by hydriodic acid reductive hydrolysis of pheomelanin, respectively. PTCA determination was performed by a method modified from a previous report (Wakamatsu et al., 2003). The eumelanin and pheomelanin content were calculated by multiplying those of PTCA and 4-AHP by factors of 25 and 9, respectively (Wakamatsu and Ito, 2002).

Minimal erythematous dose (MED) determination

Animals of the indicated genetic status were depillated with surgical shears and topical depilatory cream (Nair©) used as directed one day prior to irradiation. Mice were then sedated with ketamine/xylazine according to standard veterinary dosing (Xu et al., 2007) and UV-occlusive tape with holes punched in it was applied to the dorsal skin in order to facilitate multiple UVB dosing on the same animal. Mice were exposed to UV irradiation in a custom-made lucite chamber (Plastic Design Corporation, Massachusetts) outfitted with a double bank of UVB lamps (UV Products, Upland, CA). UV emittance was measured with the use of a UV photometer (UV Products, Upland, CA) equipped with UVB measuring head and spectral output of the lamps was determined to be roughly 75% UV-B and 25% UV-A. Edema and/or erythema of the UV-exposed areas was scored visually 24h after irradiation, and the minimal erythematous dose (MED) was calculated as the minimal dose of radiation needed to cause erythema and/or edema of the entire circle of exposed skin.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons of MED between cohorts of animals were evaluated by a Tukey’s post-test. Differences were considered statistically significant if the p value was < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Cynthia Long (University of KY histopathologycore) for technical help and Dr. Michael Jay and Melissa Howard (University of KY College of Pharmacy) for assistance with tissue lyophilization. We also thank Dr. David Fisher (Harvard Medical School) for general support and helpful suggestions. Funding sources include the Wendy Will Case Cancer Research Fund, the National Cancer Institute (R03 CA125782-01A1; R21 CA127052-01A1), the Kentucky Tobacco Research and Development Council, the Markey Cancer Foundation and the Jennifer and David Dickens Melanoma Research Foundation. MLS was supported by the Graduate Center for Toxicology’s Department of Health and Human Service Public Health Services Grant T32 ES-07266-17.

References

- 1.Abdel-Malek Z, Swope VB, Suzuki I, Akcali C, Harriger MD, Boyce ST, Urabe K, Hearing VJ. Mitogenic and melanogenic stimulation of normal human melanocytes by melanotropic peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1789–1793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel-Malek ZA, Kadekaro AL, Kavanagh RJ, Todorovic A, Koikov LN, Mcnulty JC, Jackson PJ, Millhauser GL, Schwemberger S, Babcock G, et al. Melanoma prevention strategy based on using tetrapeptide alpha-MSH analogs that protect human melanocytes from UV-induced DNA damage and cytotoxicity. Faseb J. 2006;20:1561–1563. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5655fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'orazio JA, Nobuhisa T, Cui R, Arya M, Spry M, Wakamatsu K, Igras V, Kunisada T, Granter SR, Nishimura EK, et al. Topical drug rescue strategy and skin protection based on the role of Mc1r in UV-induced tanning. Nature. 2006;443:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nature05098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franco D, De Boer PA, De Gier-De Vries C, Lamers WH, Moorman AF. Methods on in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry and beta-galactosidase reporter gene detection. Eur J Morphol. 2001;39:169–191. doi: 10.1076/ejom.39.3.169.4670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han R, Baden HP, Brissette JL, Weiner L. Redefining the skin's pigmentary system with a novel tyrosinase assay. Pigment Cell Res. 2002;15:290–297. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2002.02027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill HZ, Hill GJ. UVA, pheomelanin and the carcinogenesis of melanoma. Pigment Cell Res. 2000;138(Suppl 8):140–144. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.13.s8.25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito S. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of eu- and pheomelanin in melanogenesis control. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:166S–171S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunisada T, Lu SZ, Yoshida H, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa S, Mizoguchi M, Hayashi S, Tyrrell L, Williams DA, Wang X, et al. Murine cutaneous mastocytosis and epidermal melanocytosis induced by keratinocyte expression of transgenic stem cell factor. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1565–1573. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Fur N, Kelsall SR, Mintz B. Base substitution at different alternative splice donor sites of the tyrosinase gene in murine albinism. Genomics. 1996;37:245–248. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackenzie LA. The analysis of the ultraviolet radiation doses required to produce erythemal responses in normal skin. Br J Dermatol. 1983;108:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb04572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackenzie MA, Jordan SA, Budd PS, Jackson IJ. Activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase Kit is required for the proliferation of melanoblasts in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 1997;192:99–107. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robbins LS, Nadeau JH, Johnson KR, Kelly MA, Roselli-Rehfuss L, Baack E, Mountjoy KG, Cone RD. Pigmentation phenotypes of variant extension locus alleles result from point mutations that alter MSH receptor function. Cell. 1993;72:827–834. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosdahl IK. Local and systemic effects on the epidermal melanocyte population in UV-irradiated mouse skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:306–309. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12531840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samokhvalov A, Hong L, Liu Y, Garguilo J, Nemanich RJ, Edwards GS, Simon JD. Oxidation potentials of human eumelanosomes and pheomelanosomes. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:145–148. doi: 10.1562/2004-07-23-RC-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayre RM, Desrochers DL, Wilson CJ, Marlowe E. Skin type, minimal erythema dose (MED), and sunlight acclimatization. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:439–443. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeuchi S, Zhang W, Wakamatsu K, Ito S, Hearing VJ, Kraemer KH, Brash DE. Melanin acts as a potent UVB photosensitizer to cause an atypical mode of cell death in murine skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15076–15081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403994101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakamatsu K, Fujikawa K, Zucca FA, Zecca L, Ito S. The structure of neuromelanin as studied by chemical degradative methods. J Neurochem. 2003;86:1015–1023. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wakamatsu K, Ito S. Advanced chemical methods in melanin determination. Pigment Cell Res. 2002;15:174–183. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2002.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Q, Ming Z, Dart AM, Du XJ. Optimizing dosage of ketamine and xylazine in murine echocardiography. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:499–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye T, Simon JD. The action spectrum for generation of the primary intermediate revealed by ultrafast absorption spectroscopy studies of pheomelanin. Photochem Photobiol. 2003;77:41–45. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)077<0041:tasfgo>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zappi E, Lombardo W. Combined Fontana-Masson/Perls' staining. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6(Suppl):143–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]