Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) remains a challenging public-health issue in China. Hepatitis B carriers and patients suffer not only physically but also experience strong discrimination and stigma. China's rural population is 629 million. Thus, there is a great need to understand the situation surrounding HBV-related discrimination in everyday life in rural China. We studied 6,538 participants (≥18 y old) from 42 villages across 7 provinces (districts). Many studies have addressed discrimination against those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). However, few studies have addressed HBV-related discrimination. We found that the fear of HBV infection, not lack of knowledge about it, predominantly leads to HBV-related discrimination (although limited knowledge is also a cause). Notably, receiving the HBV vaccination contributes to reduced discrimination. In addition, the existence of fewer misunderstandings about false HBV transmission routes plays a more important role in discrimination than does understanding of true HBV transmission routes. Therefore, to reduce HBV-related discrimination, policy makers should consider eliminating HBV-related fear, strengthening adult HBV immunization programs, developing large-scale education dissemination about HBV transmission routes and non-transmission routes, and paying greater attention to target populations.

Keywords: discrimination, HBV vaccination, Knowledge, Rural China

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is one of the most serious and prevalent diseases, affecting more than 2 billion people globally.1 In China, hepatitis B remains a particularly challenging public health issue.2 In 2006, the rate of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)in the Chinese population (aged 1–59 years) was 7.2%, and it is estimated that 93 million people in China are HBV carriers.3 HBV carriers and hepatitis B patients suffer not only physical injury but also experience significant discrimination and stigma. Perceived discrimination negatively impacts individuals' self-identity and quality of life.4

Historically, HBV carriers have experienced discrimination when applying for jobs or educational opportunities. Although some companies and schools still require HBV test results,5 marked changes have taken place since the Chinese government developed policies banning HBV checkups as a condition for employment and school enrollment. However, there are no indications that HBV-related discrimination in everyday life has lessened. Hepatitis B patients and HBV carriers still experience hardship and feelings of isolation. China's rural population of 629,610,0006 is more vulnerable to experiencing lower socioeconomic status and education, among other issues, compared with those living in more urban areas. If serious discrimination against hepatitis B patients existed in rural China, then both patients and HBV carriers would endure even greater hardship. Thus, there is a great need to assess the climate of hepatitis B- and HBV-related discrimination in everyday life among the rural Chinese population. In addition, understanding potential influencing factors is necessary for developing strategies to reduce discrimination.

We defined discrimination against hepatitis B patients and HBV carriers (referred to here as HBV-related discrimination) as (1) negatively judging and unfairly treating hepatitis B patients or HBV carriers and (2) such judgment and treatment being a result of the patients' or carriers' HBV infection status. We generally divide HBV-related discrimination into 2 general types: discrimination in an employment or school enrollment situation and discrimination in everyday life by strangers, neighbors, co-workers, friends or family, and more distant relatives. In this study, we focused only on HBV-related discrimination in everyday life.

The World Health Organization and partners created World Hepatitis Day in 2014 with the theme “Hepatitis, think again.”7 To some extent, HBV-related discrimination has become worse than the disease itself. To avoid being labeled a ‘hepatitis B patient’ or ‘carrier,’ individuals usually attempt to hide their infection status, and HBV-related discrimination has become a barrier to regular screening, diagnosis, and treatment.8,9 Thus, HBV-related discrimination does not effectively protect a vulnerable population from HBV infection, and it might indirectly lead to further spread of HBV infection. It is time to think carefully about HBV-related discrimination.

Although many studies have addressed HIV- or HCV-related discrimination,10-15 studies on HBV-related discrimination are rare. Even rarer are studies that have assessed factors that contribute to HBV-related discrimination in everyday life. Nearly all studies have presumed that a lack of knowledge about hepatitis B and HBV are the major reasons for HBV-related discrimination.5,16,17 However, a recent study in China examined HBV-related discrimination in school enrollment and found that fear of infection was the main cause of discrimination.18 Therefore, this study's primary goal is to explore the factors that contribute to HBV-related discrimination. Vaccines are one of the most useful public health interventions for combating infectious diseases,19 and the hepatitis B vaccine is the most effective prevention for HBV infection.20 As such, we also sought to assess whether people who had received the hepatitis B vaccination might exhibit lower levels of HBV-related discrimination.

Policy makers need evidence on the effectiveness of interventions, but no study has empirically and quantitatively tested the reasons for HBV-related discrimination. With the intent of providing a clearer picture, we sought to quantitatively assess the HBV-related discrimination situation in rural China, to determine whether lack of knowledge is the key influencing factor and to identify additional factors that may affect the prevalence of HBV-related discrimination.

Results

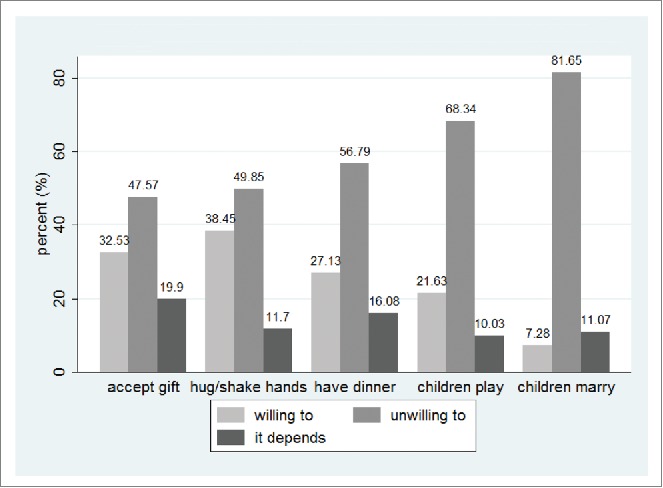

Figure 1 summarizes the participants' attitudes toward hepatitis B patients and carriers. Of all the participants, only 32.53%, 38.45%, and 27.13% were willing to accept gifts from hepatitis B patients or carriers, hug and shake hands with them, or have dinner with them, respectively. What is more serious is that only 21.63% of the participants thought parents should let their children play with hepatitis B-infected children, and only 7.28% thought parents should allow their children to marry hepatitis B patients or carriers.

Figure 1.

Attitude toward hepatitis B patients and carriers.

Table 2 shows the HBV-related discrimination distribution. The median score was 8, and only 4.79% had no sign of HBV-related discrimination. However, 36.17% scored at the highest level, indicating that they were firmly unwilling to make contact with hepatitis B patients or carriers. According to their HBV-related discrimination index scores, the participants were divided into 3 groups. Table 3 shows the group-based HBV-related distribution, with 57.51% of participants in the severe discrimination group. Table 4 shows the characteristics of the 3 HBV-related discrimination groups.

Table 2.

Hepatitis B discrimination index score

| Score | Freq. | Percent | Cum. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 313 | 4.79 | 4.79 |

| 1 | 233 | 3.56 | 8.53 |

| 2 | 511 | 7.82 | 16.17 |

| 3 | 191 | 2.92 | 19.09 |

| 4 | 526 | 8.05 | 27.13 |

| 5 | 458 | 7.01 | 34.14 |

| 6 | 546 | 8.35 | 42.49 |

| 7 | 400 | 6.12 | 48.61 |

| 8 | 630 | 9.64 | 58.24 |

| 9 | 365 | 5.58 | 63.83 |

| 10 | 2365 | 36.17 | 100.00 |

| Total | 6538 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Table 3.

Hepatitis B discrimination level

| Discrimination Level | Freq. | Percent | Cum. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild or without discrimination | 1248 | 19.09 | 19.09 |

| Medium discrimination | 1530 | 23.40 | 42.49 |

| Severe discrimination | 3760 | 57.51 | 100.00 |

| Total | 6538 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Table 4.

Hepatitis B discrimination level of participants with different characteristics (N = 6538)

| Mild/without |

Medium |

Severe |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Male | 561 | 21.73 | 609 | 23.59 | 1412 | 54.69 |

| Female | 687 | 17.37 | 921 | 23.28 | 2348 | 59.35 |

| Age 18–28 | 242 | 24.42 | 300 | 30.27 | 449 | 45.31 |

| Age 28–38 | 334 | 24.58 | 376 | 27.67 | 649 | 47.76 |

| Age 38–48 | 295 | 17.45 | 380 | 22.47 | 1016 | 60.08 |

| Age 48–58 | 208 | 16.07 | 264 | 20.40 | 822 | 63.52 |

| Age 58- | 169 | 14.05 | 210 | 17.46 | 824 | 68.50 |

| Low education | 474 | 17.34 | 527 | 19.28 | 1732 | 63.37 |

| Medium education | 502 | 17.50 | 739 | 25.77 | 1627 | 56.73 |

| High education | 272 | 29.03 | 264 | 28.18 | 401 | 42.80 |

| Farmer | 724 | 16.83 | 937 | 21.78 | 2641 | 61.39 |

| Unemployed | 89 | 20.00 | 108 | 24.27 | 248 | 55.73 |

| Migratory workers | 186 | 21.11 | 231 | 26.22 | 464 | 52.67 |

| Other occupation | 191 | 25.30 | 210 | 27.81 | 354 | 46.89 |

| Public officers | 58 | 37.42 | 44 | 28.39 | 53 | 34.19 |

| Without vaccination history | 937 | 17.70 | 1184 | 22.36 | 3174 | 59.94 |

| Received vaccination | 311 | 25.02 | 346 | 27.84 | 586 | 47.14 |

| Household income group 1 | 150 | 16.69 | 197 | 21.91 | 552 | 61.40 |

| Household income group 2 | 287 | 20.28 | 331 | 23.39 | 797 | 56.33 |

| Household income group 3 | 280 | 17.85 | 358 | 22.82 | 931 | 59.34 |

| Household income group 4 | 294 | 18.89 | 371 | 23.84 | 891 | 57.26 |

| Household income group 5 | 237 | 21.57 | 273 | 24.84 | 589 | 53.59 |

| Knowledge of true transm. route 1 | 392 | 19.43 | 406 | 20.13 | 1219 | 60.44 |

| Knowledge of true transm. route 2 | 499 | 20.38 | 637 | 26.01 | 1313 | 53.61 |

| Knowledge of true transm. route 3 | 357 | 17.23 | 487 | 23.50 | 1228 | 59.27 |

| Knowledge of false transm. route 1 | 241 | 12.51 | 407 | 21.12 | 1279 | 66.37 |

| Knowledge of false transm. route 2 | 499 | 20.62 | 635 | 26.24 | 1286 | 53.14 |

| Knowledge of false transm. route 3 | 508 | 23.19 | 488 | 22.27 | 1195 | 54.54 |

| Knowledge of true symptoms 1 | 742 | 19.47 | 830 | 21.78 | 2239 | 58.75 |

| Knowledge of true symptoms 2 | 302 | 17.74 | 472 | 27.73 | 928 | 54.52 |

| Knowledge of true symptoms 3 | 204 | 19.90 | 228 | 22.24 | 593 | 57.85 |

| No fear of being infected with HBV | 1059 | 32.22 | 1022 | 31.09 | 1206 | 36.69 |

| Fear of being infected with HBV | 189 | 5.81 | 508 | 15.63 | 2554 | 78.56 |

The HBV vaccination coverage rate varied across age groups: 18–28 y (45.9%, n = 991), 28–38 (26.3%, n = 1359), 38–48 (15.1%, n = 1691), 48–58 (9.4%, n = 1294), and 58+ (4.4%, n = 1203). For the 2 youngest age groups, the mean discrimination score was lower for vaccinated than for unvaccinated individuals. For the age group of 18–28 years, the mean discrimination scores were 5.59 and 6.38 for the vaccinated and unvaccinated, respectively (p = 0.000). For the age group of 28–38 years, the scores were 5.57 and 6.32 (p = 0.000). For the 3 older age groups, and at conventional significance levels, the means were not different, and Mann Whitney U tests did not indicate that the distribution of discrimination scores differed between the vaccinated and unvaccinated. The joint mean discrimination scores were 6.91 (SE = 0.0776), 7.17 (SE = 0.0897) and 7.49 (SE = 0.0907) for the age groups 38–48, 48–58 and 58+, respectively.

The univariate multinomial logistic regression analysis of HBV-based discrimination and “knowledge of hepatitis B symptoms” levels was not statistically significant and was eliminated when running the multiple multinomial logistic regression analysis. Table 5 shows the results of the multiple multinomial logistic regression of HBV-based discrimination levels against explanatory factors. The results for the outcomes of medium discrimination and severe discrimination were related to the basis outcome, mild discrimination or no discrimination. For the medium discrimination outcome, several estimated coefficients and relative risk ratios (RRR) were statistically significant. For the severe discrimination outcome, nearly all estimated coefficients and RRR were statistically significant, except for household income. To simplify the discussion, we will focus mainly on the results of the severe discrimination outcome.

Table 5.

Multiple polychotomous logistic regression of Hepatitis B discrimination level against explanatory factors (N=6538)

| Medium discrimination |

Severe discrimination |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | RRR | P | Coef. | SE | RRR | P | |

| Female | 0.180 | 0.083 | 1.197 | 0.030 | 0.214 | 0.078 | 1.239 | 0.006 |

| Age 28–38 | −0.156 | 0.120 | 0.855 | 0.192 | −0.136 | 0.121 | 0.873 | 0.260 |

| Age 38–48 | −0.033 | 0.125 | 0.968 | 0.793 | 0.397 | 0.122 | 1.488 | 0.001 |

| Age 48–58 | 0.004 | 0.138 | 1.004 | 0.978 | 0.551 | 0.132 | 1.734 | 0.000 |

| Age 58– | 0.080 | 0.154 | 1.083 | 0.603 | 0.862 | 0.145 | 2.369 | 0.000 |

| Medium education | 0.337 | 0.092 | 1.400 | 0.000 | 0.163 | 0.086 | 1.178 | 0.056 |

| High education | 0.017 | 0.126 | 1.018 | 0.890 | −0.397 | 0.122 | 0.672 | 0.001 |

| Unemployed | −0.110 | 0.159 | 0.896 | 0.488 | −0.295 | 0.151 | 0.744 | 0.050 |

| Migratory workers | −0.002 | 0.117 | 0.998 | 0.986 | −0.092 | 0.112 | 0.912 | 0.411 |

| Other occupations | −0.054 | 0.124 | 0.947 | 0.661 | −0.232 | 0.121 | 0.793 | 0.056 |

| Public officers | −0.307 | 0.226 | 0.735 | 0.174 | −0.790 | 0.236 | 0.454 | 0.001 |

| Received vaccination | −0.114 | 0.100 | 0.893 | 0.256 | −0.232 | 0.098 | 0.793 | 0.018 |

| Household income group 2 | −0.186 | 0.139 | 0.830 | 0.183 | −0.166 | 0.130 | 0.847 | 0.203 |

| Household income group 3 | −0.085 | 0.141 | 0.919 | 0.548 | 0.081 | 0.132 | 1.085 | 0.537 |

| Household income group 4 | −0.091 | 0.142 | 0.913 | 0.520 | 0.049 | 0.134 | 1.050 | 0.714 |

| Household income group 5 | −0.170 | 0.152 | 0.844 | 0.265 | −0.041 | 0.144 | 0.960 | 0.776 |

| Knowledge of true transm. route 2 | 0.091 | 0.097 | 1.096 | 0.345 | −0.319 | 0.091 | 0.727 | 0.000 |

| Knowledge of true transm. route 3 | 0.095 | 0.109 | 1.100 | 0.382 | −0.181 | 0.102 | 0.834 | 0.076 |

| Knowledge of false transm. route 2 | −0.255 | 0.104 | 0.775 | 0.014 | −0.687 | 0.099 | 0.503 | 0.000 |

| Knowledge of false transm. route 3 | −0.560 | 0.112 | 0.571 | 0.000 | −0.989 | 0.105 | 0.372 | 0.000 |

| Fear of being infected | 1.030 | 0.097 | 2.801 | 0.000 | 2.462 | 0.088 | 11.727 | 0.000 |

The basis outcome is mild or without discrimination.

Discussion

It is clear that hepatitis B patients and carriers need more social support and care. Instead, they suffer from HBV-related discrimination and live difficult lives. These results show that HBV-related discrimination in rural China is widespread. This issue should not be underestimated or ignored.

We found that females had higher discrimination scores. This finding was inconsistent with a previous study in Japan showing that gender was unassociated with prejudice toward HIV-, HBV-, or HCV-infected colleagues.21

In the current study, our hypothesis was that income was associated with HBV-related discrimination, but the results were in striking contrast to the hypothesis. Participants' discrimination levels did not significantly differ based on income. This was consistent with the findings of the Japanese study.2 However, that study used individual income, whereas we used household income.

Our findings suggested that old age was positively associated with severe HBV-related discrimination. Compared with those aged 18–28 y old, participants aged 38–48, 48–58, and 58+ years old showed more severe discrimination with increasing RRR (1.488, 1.734, and 2.369, respectively). This is contrary to the finding that older age was associated with decreased prejudice toward HBV- or HCV-infected colleagues in the Japanese study.21

We found that individuals with higher education tended to have less severe discrimination compared with those with less education (the reference education group), and the severe discrimination rate of those with a medium education level did not differ from that of the low education group. No previous study has assessed the influence of education on HBV-related discrimination, although a study in China showed that providers with higher medical education tended to show higher levels of discrimination against those with HIV.22

We also determined that occupation affected the level of HBV-related discrimination. Public officers (e.g., civil servants, village doctors, or teachers) were less likely to exhibit severe HBV-related discrimination compared with farmers. However, although village doctors had lower levels of HBV-related discrimination, discrimination was extensively present in this group. Of the 43 village doctors in our sample, only 4 doctors (9.30%) reported having no HBV-related discrimination, whereas 15 doctors (34.88%) reported severe discrimination. Ten (23.26%) of them were afraid of being infected with HBV. According to a study of medical students, positive correlations exist between greater knowledge and positive attitude toward hepatitis B.23 This is consistent with our finding that village doctors' knowledge of hepatitis B and HBV was limited: only 23 (53.49%) had the highest knowledge of HBV transmission routes, and only 20 (46.51%) knew that mosquito or insect bites and having dinner with patients or carriers cannot lead to HBV transmission. Village doctors play a very important role in disseminating health-related knowledge and promoting health outcomes in rural China. Our results indicate that equipping village doctors with knowledge about hepatitis B and HBV through the provision of in-depth training is of great urgency and importance. A study in China has shown that adequate training is effective in improving Chinese village doctors' hepatitis B-related knowledge. 24

Receiving a vaccination was related to reduced HBV-related discrimination scores, suggesting that HBV vaccination not only effectively protects vulnerable people from HBV infection,25,26 it also reduces their levels of HBV-related discrimination. This circumstance probably occurs because individuals feel a stronger sense of security because they are not as vulnerable to HBV. Our study also found that older age was positively associated with more severe discrimination and that the HBV vaccination coverage rate decreased with advancing age. Therefore, treating older people as a key population, including encouraging older people to receive the HBV vaccination, is expected to help reduce HBV-related discrimination. Based on a previous study, the hepatitis B vaccination coverage rate among rural-dwelling Chinese adults is 20.8% (those who have received at least one dose), and higher rates are obtainable by reducing the related economic burden of the vaccination.27

A 2013 study indicated that the level of HBV awareness is low in rural Chinese populations.28 In addition, some studies have noted that ignorance about HBV, especially misunderstandings about its transmission routes, is the main cause of discrimination.5,16 Similarly, our study shows that increasing knowledge about false transmission routes may greatly reduce the probability of severe HBV-related discrimination. However, in our study, the level of discrimination was not associated with knowledge about true transmission routes. Only medium-level knowledge about true routes was statistically significant compared with the low-knowledge group. However, the group with high-level knowledge about the true routes of transmission was not significantly different from the low-level knowledge group. In addition, there was a large gap between the RRRs (0.503, 0.372) for knowledge of false transmission routes and the RRR (0.727) of the true transmission routes, suggesting that correcting individuals' misunderstandings of false transmission routes is more helpful than emphasizing information about true transmission routes. This study also revealed that the variable “knowledge of hepatitis B symptoms” had no relation to HBV-related discrimination. Mother-to-child transmission is the leading cause of HBV infection in China.29 We suggest that informing people that a significant proportion of infection is accounted for by mother-to-child transmission. This perspective might be helpful in reducing HBV-related discrimination.

Very few studies have tested the association between the “fear of being infected with HBV” and HBV-related discrimination. A qualitative study in China showed that the fear of HBV infection risk was the primary cause of HBV-related discrimination.18 In our quantitative study, the coefficient of the “fear of being infected with HBV” was 2.462, and its RRR relative to the reference group of “no fear of being infected” was as high as 11.727. Thus, it is clear that the “fear of being infected with HBV” was the most important cause of HBV-related discrimination in our study. However, this finding is inconsistent with most previous qualitative studies that have shown that discrimination stems from ignorance about HBV and the way it is transmitted. Further, although our findings suggest that the fear of infection greatly contributes to severe discrimination levels, we did not conduct an in-depth assessment of the origins of that fear. We discuss this issue in detail in the paragraph on limitations.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that HBV-related discrimination in rural China is serious, and this discrimination involves several associated factors. The fear of HBV infection is the main factor associated with HBV-related discrimination, not a lack of related knowledge, although the latter was also a factor to a lesser degree. Notably, receiving the HBV vaccination is associated with less discrimination, and misunderstandings involving false HBV transmission routes plays a more important role than an understanding of true HBV transmission routes. In addition, older adults and those with less education are more likely to exhibit severe discrimination against hepatitis B patients and carriers. Public officers harbor less HBV-related discrimination. Therefore, to accelerate the control of HBV-related discrimination, policy makers should consider eliminating HBV-related fear, strengthening adult HBV immunization programs, developing large-scale dissemination of knowledge about true and false HBV transmission routes, and paying more attention to the key discriminating populations. It also should be noted that the dissemination of knowledge must start with training village doctors. A future in-depth study is planned to examine whether the fear of HBV infection is exaggerated and the factors that cause this fear and will be implemented in the near future.

Although this study is of great significance, due to both the topic and our use of quantitative methods, it is not without potential limitations. First, the measurement of HBV-related discrimination in the real world includes, but is not limited to, people's attitudes toward the 5 items assessed in our questionnaire. For example, we can also speculate that people may tend toward HBV-related discrimination if they are unwilling to work with a colleague who is a hepatitis B patient or carrier. Second, we did not include all possible true or false transmission routes, so the variables “knowledge of true transmission routes” and “knowledge of false transmission routes” may be over- or underestimated. Third and most important is that we simply asked participants whether they feared being infected with HBV when spending time with hepatitis B patients or carriers; we did not assess the factors that may lead to their fear of infection. Are they afraid because there is no cure for HBV? Are they afraid because most are risk averse despite the extremely small risk of infection? Does this fear originate from their sense of responsibility for caring for themselves and their loved ones? Perhaps the fear stems from something else, such as the unique Chinese public opinion environment, social–cognitive factors, or the disease-related economic burden. Clearly, further studies are needed to evaluate the origins of this fear.

Participants and Methods

Study participants and sampling method

The study participants were from 42 villages across 7 provinces with notable regional, economic, and epidemiological diversity: Beijing, Hebei, Shandong, Heilongjiang, Hainan, Ningxia, and Jiangsu. The participant characteristics are shown in detail in Table 1, and all independent variables are explained below. We stratified the counties by the level of economic development (low, medium, high) and then stratified the villages within counties by the distance to hepatitis B vaccination sites (short, medium, long). In larger villages, households were randomly extracted by using household size to create weighted sampling (probability proportionate to size). All households in small villages were sampled. The participation rate was approximately 82%, and the predominant reason for nonparticipation was that all household members had moved to industrialized regions.27 The sample consisted of 32,311 individuals (all ages included) from 8,637 households. After excluding the records that were from a family member on behalf of the intended participant due to their absence, the final sample was 6,538 adults (age ≥18 years). Juveniles were not included on the basis that they have not developed stable opinions. We used a self-designed interview questionnaire with questions about individual and household characteristics, attitudes toward hepatitis B patients and carriers, knowledge about hepatitis B and HBV, and individual vaccination history. Well-trained staff administered the interviews after a pilot survey.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for independent variables (N=6538)

| Variable | Variable definition | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1 if male; 0 otherwise | 2582 | 39.49 |

| Female | 1 if female; 0 otherwise | 3956 | 60.51 |

| Age 18–28 | 1 if aged 18–28; 0 otherwise | 991 | 15.16 |

| Age 28–38 | 1 if aged 28–38; 0 otherwise | 1359 | 20.79 |

| Age 38–48 | 1 if aged 38–48; 0 otherwise | 1691 | 25.86 |

| Age 48–58 | 1 if aged 48–58; 0 otherwise | 1294 | 19.79 |

| Age 58- | 1 if aged 58-; 0 otherwise | 1203 | 18.40 |

| Low education | 1 if years of schooling<=6 years; 0 otherwise | 2733 | 41.80 |

| Medium education | 1 if 6< years of schooling<=9 years; 0 otherwise | 2868 | 43.87 |

| High education | 1 if years of schooling>9years; 0 otherwise | 937 | 14.33 |

| Farmer | 1 if farmer; 0 otherwise | 4302 | 65.80 |

| Unemployed | 1 if unemployed; 0 otherwise | 445 | 6.81 |

| Migratory workers | 1 if migratory workers; 0 otherwise | 881 | 13.48 |

| Public officers | 1 if public civil servants, doctors or teachers; 0 otherwise | 155 | 2.37 |

| Other occupations | 1 if not farmer, unemployed, migratory workers, or public officers; | 755 | 11.55 |

| Without vaccination history | 1 if received 0 dose of HBV vaccine; 0 otherwise | 5295 | 80.99 |

| Received vaccination | 1 if received at least 1 dose of HBV vaccine; 0 otherwise | 1243 | 19.01 |

| Household income group 1 | 1 if household income in the bottom quintile; 0 otherwise | 899 | 13.75 |

| Household income group 2 | 1 if household income in the second lowest quintile; 0 otherwise | 1415 | 21.64 |

| Household income group 3 | 1 if household income in the middle quintile; 0 otherwise | 1569 | 24.00 |

| Household income group 4 | 1 if household income in the second lowest quintile; 0 otherwise | 1556 | 23.80 |

| Household income group 5 | 1 if household income in the top quintile; 0 otherwise | 1099 | 16.81 |

| Knowledge of true transm. route 1 | 1 if identify 0/1 true route of transmission; 0 otherwise | 2017 | 30.85 |

| Knowledge of true transm. route 2 | 1 if identify 2/3 true route of transmission; 0 otherwise | 2449 | 37.46 |

| Knowledge of true transm. route 3 | 1 if identify 4/5 true route of transmission; 0 otherwise | 2072 | 31.69 |

| Knowledge of false transm. route 1 | 1 if identify 0 false route of transmission; 0 otherwise | 1927 | 29.47 |

| Knowledge of false transm. route 2 | 1 if identify 1 false route of transmission; 0 otherwise | 2420 | 37.01 |

| Knowledge of false transm. route 3 | 1 if identify 2 false routes of transmission; 0 otherwise | 2191 | 33.51 |

| Knowledge of true symptoms 1 | 1 if identify 0/1/2 true symptoms; 0 otherwise | 3811 | 58.29 |

| Knowledge of true symptoms 2 | 1 if identify 3/4 true symptoms; 0 otherwise | 1702 | 26.03 |

| Knowledge of true symptoms 3 | 1 if identify >=5 true symptoms; 0 otherwise | 1025 | 15.68 |

| No fear of being infected with HBV | 1 if no fear of being infected; 0 otherwise | 3287 | 50.28 |

| Fear of being infected with HBV | 1 if fear of being infected; 0 otherwise | 3251 | 49.72 |

Definition and measurement of dependent variables

The dependent variable, HBV-related discrimination level, is categorical with 3 outcomes: mild or without discrimination, medium discrimination, and severe discrimination. Specifically, participants were asked about their attitudes toward 5 events, which were used to measure the extent of their HBV-related discrimination. The five events were the following: “Are you willing to accept gifts from hepatitis B patients or carriers?;” “Are you willing to have dinner with them?;” “Are you willing to shake hands with or hug them?;” “Do you think parents should let their children play with hepatitis B-infected children?;” and “Do you think parents should accept their child marrying a hepatitis B-infected person?.” For each event, participants were offered 3 options: “yes” (0), “no” (2) and “it depends” (1). We calculated an HBV-related discrimination index score for each participant as the sum of their response scores for the 5 events (range 0–10). Higher scores indicated greater discrimination. Participants were then categorized in one of 3 HBV-related discrimination levels based on their HBV-related discrimination index score: mild or without discrimination level (scores 0–3), medium discrimination level (scores 4–6), and severe discrimination level (scores 7–10).

Definition and measurement of independent variables

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all independent variables. We divided participants into 2 groups based on vaccination status: those who had never received the HBV vaccine were in the “without vaccination history” group, and those who had received one or more doses of the HBV vaccine were in the “received vaccination” group.

Household income was the average annual income of all household members during the past 5 y Five groups were created based on the household's relative position to the quintiles of the household income distribution. The quintiles were 10,000, 20,000, 30,000 and 40,000. Because there were many individuals whose household income was exactly equal to the cut-off points, the sample proportion belonging to each household income group differs from 20%.

Participants were asked to identify the 5 true HBV transmission routes: mother to child, unclean medical or dental equipment, unprotected sex, unhygienic tattooing or ear-piercing, and sharing shaving equipment with an infected person. We counted the number of true transmission routes identified by each participant, and the variable “knowledge of true transmission routes” was divided into 3 levels according to the identified number. Specifically, participants who identified 0–1 true transmission routes belonged to group 1; those who identified 2–3 were in group 2; and those who identified 4–5 were in group 3.

Participants were also asked whether they endorsed either of 2 false transmission routes: whether eating with HBV patients or carriers is an HBV transmission route and whether mosquito or insect bites might lead to HBV infection. These constituted the variable “knowledge of false transmission routes” (range 0–2).

Participants were also asked to identify hepatitis B symptoms. Nine true symptoms were listed (e.g.,, jaundice, yellow urine, fever). The number of true symptoms identified was used to create the variable “knowledge of true symptoms” with 3 levels according to the identified number.

The participants were asked to explain whether they felt fearful and worried about being infected with HBV while spending time with hepatitis B patients and carriers. Two groups were created: “fear of being infected with HBV” and “no fear of being infected with HBV.”

Statistical analyses

All data were double-inputted using Microsoft Access and checked for consistency. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 12.0. Multinomial logistic regression analyses were used to assess the associations between each independent variable and HBV-related discrimination level. A two-tailed p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

Participants were informed that they could refuse to answer any question. The questionnaire did not ask about infection status, and no biological samples were collected. The project was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee at the Shandong University School of Medicine (Grant No. 201001052).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the health workers in all the participating provinces for their support and assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the Norwegian Research Council (Project no. 196400/S50).

References

- 1.Trepo C, Chan HLY, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. LANCET 2014; 384:2053-63; PMID:24954675; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J, Fan DM. Hepatitis B in China. LANCET 2007; 369:1582-3; PMID:17499584; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60723-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang CY, Zhong YS, Guo LP. Strategies to prevent hepatitis B virus infection in China:Immunization,screening,and standard medical practices. Biosci Trends 2013; 7:7-12; PMID:23524888 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drazic YN, Caltabiano ML. Chronic hepatitis B and C: Exploring perceived stigma,disease information,and health-related quality of life. Nurs Health Sci 2013; 15:172-178; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/nhs.12009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang T, Wu MC. Discrimination against hepatitis B carriers in China. LANCET 2011; 378:1059; PMID:21924982; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61460-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Bureau of Statistics of China Population Profile. http://data.stats.gov.cn/search/keywordlist2;jsessionid=B0495BED7D6D8FC01199D594112DF3B8?keyword=%E4%BA%BA%E5%8F%A3

- 7.WHO Hepatitis:think again. 2014; http://www.who.int/campaigns/hepatitis-day/2014/event/en/

- 8.Sriphanlop P, Jandorf L, Kairouz C, Thelemaque L, Shankar H, Perumalswami P. Factors related to hepatitis B screening among Africans in New York city. Am J Health Behav 2014; 38:745-54; PMID:24933144; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5993/AJHB.38.5.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotler SJ, Cotler S, Xie H, Luc BJ, Layden TJ, Wong SS. Characterizing hepatitis B stigma in Chinese immigrants. J Viral Hepat 2012; 19:147-152; PMID:22239504; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01462.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman CI, Stangl AL. Editorial:Global action to reduce HIV stigma and discrimination. J Int AIDS Soc 2013; 16:18881; PMID:24242269; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nostlinger C, Castro DR, Platteau T, Dias S, Le GJ. HIV-related discrimination in European health care settings. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 2014; 28:155-161; PMID:24568694; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/apc.2013.0247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc 2013; 16:18734; PMID:24242268; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain A, Nuankaew R, Mongkholwiboolphol N, Banpabuth A, Tuvinun R, Oranop Na Ayuthaya P, Richter K. Community-based interventions that work to reduce HIV stigma and discrimination: results of an evaluation study in Thailand. J Int AIDS Soc 2013; 16:18711; PMID:24242262; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butt G, Paterson BL, McGuinness LK. Living with the stigma of hepatitis C. West J Nurs Res 2008; 30:204-221; PMID:17630381; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/0193945907302771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marinho RT, Barreira DP. Hepatitis C,stigma and cure. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:6703-9; PMID:24187444; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan LL, Pan RH. Discrimination against hepatitis B and the rethinking of it. Med Philos 2005; 26:77-9 [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eguchi H, Wada K. Knowledge of HBV and HCV and individuals' attitudes toward HBV- and HCV-infected colleagues: a national cross-sectional study among a working population in Japan. PloS One 2013; 8:e76921; PMID:24086765; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0076921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen K. Against discrimination:the belief selection between rich knowledge and ignorance from the perspective of discrimination against HBV carriers in education. Tsinghua Law J 2008; 2:22-32 [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddiqui M, Salmon DA, Omer SB. Epidemiology of vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013; 9:2643-8; PMID:24247148; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.27243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Q, Zhuang GH, Wang XL, Hou TJ, Shah DP, Wei XL, Wang LR, Zhang M. Comparison of long-term immunogenicity (23 y) of 10 mu g and 20 mu g doses of hepatitis B vaccine in healthy children. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2012; 8:1071-1076; PMID:22854666; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.20656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eguchi H, Wada K, Smith DR. Sociodemographic factors and prejudice toward HIV and hepatitis B/C status in a working-age population: results from a national, cross-sectional study in Japan. PloS one 2014; 9:e96645; PMID:24792095; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0096645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L, Wu ZY, Zhao Y, Lin CQ, Detels R, Wu S. Using case vignettes to measure HIV-related stigma among health professionals in China. Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36:178-84; PMID:17175545; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/ije/dyl256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansour-Ghanaei R, Joukar F, Souti F, Atrkar-Roushan Z. Knowledge and attitude of medical science students toward hepatitis B and C infections. Int J Clin Exp Med 2013; 6:197-205; PMID:23573351 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang YC, Li XC, Huang DH, Guo ZW, Yan SP. Investigation on knowledge of hepatitis B prevention and evaluation of the training effect among rural doctors. Chinese Primary Health Care 2011; 25: 32-4 [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Da VG, Romano L, Sepe A, Iorio R, Paribello N, Zappa A, Zanetti AR. Impact of hepatitis B vaccination in a highly endemic area of south Italy and long-term duration of anti-HBs antibody in two cohorts of vaccinated individuals. Vaccine 2007; 25:3133-6; PMID:17280750; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang XF, Bi SL, Yang WH, Wang LD, Cui G, Cui FQ, Zhang Y, Liu JH, Gong XH, Chen YS. Evaluation of the impact of hepatitis B vaccination among children born during 1992–2005 in China. J Infect Dis 2009; 200: 39-47; PMID:19469708; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/599332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu DW, Wang J, Wangen KR. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage rates among adults in rural China: Are economic barriers relevant? Vaccine 2013; 32:6705-10; PMID:23845801; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H, Li M, Jin MJ, Jing FY, Wang H, Chen K. Public awareness of three major infectious diseases in rural Zhejiang province, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:192; PMID:23627258; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2334-13-192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui Y, Jia JD. Update on epidemiology of hepatitis B and C in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 28: 7-10; PMID:23855289; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/jgh.12220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]