Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Given the limitations in health care resources, quality-of-life measures for interventions have gained importance.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether vision-related quality-of-life outcomes were different between the natamycin and voriconazole treatment arms in the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial I, as measured by an Indian Vision Function Questionnaire.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Secondary analysis (performed October 11–25, 2014) of a double-masked, multicenter, randomized, active comparator–controlled, clinical trial at multiple locations of the Aravind Eye Care System in South India that enrolled patients with culture- or smear-positive filamentous fungal corneal ulcers who had a baseline visual acuity of 20/40 to 20/400 (logMAR of 0.3–1.3).

INTERVENTIONS

Study participants were randomly assigned to topical voriconazole, 1%, or topical natamycin, 5%.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Subscale score on the Indian Vision Function Questionnaire from each of the 4 subscales (mobility, activity limitation, psychosocial impact, and visual function) at 3 months.

RESULTS

A total of 323 patients were enrolled in the trial, and 292 (90.4%) completed the Indian Vision Function Questionnaire at 3 months. The majority of study participants had subscale scores consistent with excellent function. After adjusting for baseline visual acuity and organism, we found that study participants in the natamycin-treated group scored, on average, 4.3 points (95% CI, 0.1–8.5) higher than study participants in the voriconazole-treated group (P = .046). In subgroup analyses looking at ulcers caused by Fusarium species and adjusting for baseline best spectacle–corrected visual acuity, the natamycin-treated group scored 8.4 points (95% CI, 1.9–14.9) higher than the voriconazole-treated group (P = .01). Differences in quality of life were not detected for patients with Aspergillus or other non-Fusarium species as the causative organism (1.5 points [95% CI, −3.9 to 6.9]; P = .52).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

We found evidence of improvement in vision-related quality of life among patients with fungal ulcers who were randomly assigned to natamycin compared with those randomly assigned to voriconazole, and especially among patients with Fusarium species as the causative organism. Incorporation of quality-of-life measures in clinical trials is important to fully evaluate the effect of the studied interventions.

TRIAL REGISTRATION

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00996736

In an era of diminishing health care resources, evaluating quality-of-life measures for each medical intervention is gaining importance. The US Food and Drug Administration recommends the evaluation of the relationship between visual acuity, vision-related functioning, and therapeutic interventions.1 The National Eye Institute (NEI) has developed a 25-question visual function questionnaire that has been validated and used to evaluate outcomes of age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, low vision, diabetic retinopathy, uveitis, and dry eye syndrome.2–9

The visual needs of and the effect of visual disability on people in parts of the developing world may be quite different from those of people in developed countries. For this reason, the Indian Vision Function Questionnaire (IND-VFQ) was developed from a population of visually impaired and blind people living in 3 different geographical regions of India: Delhi, Andra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu. Initially, 45 questions were developed using focus groups, and then the number of questions was reduced to 33 after field-testing and validation.10–12 Subsequent Rasch analyses of the IND-VFQ for patients with cataracts12 suggested that a 28-question survey had better psychometric properties.

Vision loss can have a substantial effect on quality of life.6,13 In a previous cohort study14 of patients with bacterial, fungal, or viral keratitis in Shanghai, China, the NEI-VFQ composite score correlated with the final best-corrected visual acuity in the worse-seeing eye, duration of disease, and history of operation for treatment of the infectious keratitis.

The Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial I (MUTT I) was an NEI-funded, double-masked, multicenter, randomized, active comparator–controlled, clinical trial that found that topical natamycin, 5%(Natacyn; preserved with benzalkonium chloride, 0.01%), was superior to topical voriconazole, 1%(Vfend IV; reconstituted in sterile water for injection with benzalkonium chloride, 0.01%, by Aurolab), for the treatment of filamentous fungal corneal ulcers (in particular, those cases that tested positive for Fusarium species on culture).15 In our secondary analysis, we administered the IND-VFQ to MUTT I study participants 3 months after enrollment in order to evaluate vision-related quality-of-life outcomes.

Methods

The methods for the MUTT I have been outlined in detail in a previous publication (eFigure in the Supplement).15 In brief, patients who presented to one of several hospitals of the Aravind Eye Care System (Madurai, Pondicherry, or Coimbatore) in India or to the Francis I. Proctor Foundation at the University of California, San Francisco, with smear-positive filamentous fungal corneal ulcers were randomly assigned to topical natamycin, 5%, or topical voriconazole, 1%. Eligible study participants had culture- or smear positive corneal ulcers and a baseline visual acuity of 20/40 to 20/400 (logMAR of 0.3–1.3). Exclusion criteria included a coinfection with bacterial, Acanthamoeba, or herpetic keratitis; impending perforation; an age of younger than 16 years; or poor visual acuity in the other eye (<20/200). The primary outcome was best spectacle–corrected visual acuity (BSCVA) in the affected eye at 3 months.

The full 45-item IND-VFQ subscale score was a non-prespecified secondary outcome subscale score and was administered at the 3-month visit at the Indian study sites.10 The MUTT I Data Safety and Monitoring Committee performed an ongoing review for safety, data quality, and ethical conduct throughout the length of the trial. Institutional review board approval was obtained at the University of California, San Francisco, and at the Aravind Eye Care System. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the trial conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

We analyzed our data using recommendations from a Rasch analysis of the IND-VFQ by Finger et al,12 which resulted in a questionnaire with 4 subscales (mobility subscale, 6 questions; activity limitation subscale, 10 questions; psychosocial impact subscale, 5 questions; visual function subscale, 7 questions) (eTable in the Supplement). Responses to each question were categorized on a 4-point Likert scale.12 For statistical analyses, the 4-point numeric answers were converted to a 0 to 100 point scale (ie, 0, 33.3, 66.7, and 100). A score of 100 corresponded to no visual disability, whereas a score of 0 corresponded to an inability to perform the task owing to poor vision. The question responses were averaged within each subscale score for each study participant, generating 4 continuous subscale scores. The subscale scores were compared between treatment groups using a generalized estimating equation, allowing for clustering (nonindependence of outcomes) of within-participant subscale scores around the patient and controlling for BSCVA, as well as controlling for whether or not the etiologic organism was Fusarium species. Subgroup analyses were performed for ulcers due to Fusarium species, Aspergillus species, or some other fungal organisms. Sample size calculation for the MUTT I was based on the primary outcome of BSCVA. The chosen sample size of 368 study participants would provide 80% power to detect a difference of 0.15 logMAR (Snellen equivalent, 20/32) in visual acuity (or 1.5 lines of visual acuity) between treatment arms, assuming a standard deviation of 0.46 and a 2-tailed α level of .05. All analyses were conducted with Stata version 13.0.

Results

A total of 323 patients were enrolled in the MUTT I between April 3, 2010, and December 31, 2011, at multiple locations of the Aravind Eye Care System. At that point, recruitment was suspended because of a significant difference between treatment arms in corneal perforations and the need for therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty. The results of the IND-VFQ were available for 292 of 323 patients. We found no evidence that loss to follow-up was associated with any baseline characteristics, infecting organism, or treatment arm. The baseline characteristics of the study participants who completed the IND-VFQ are outlined in Table 1. Among those participants in the voriconazole- and natamycin-treated arms of the study who completed the IND-VFQ, there were 15 and 9 corneal perforations, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants Completing the IND-VFQa

| Baseline Characteristic | Treatment Arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Voriconazole (n = 146) |

Natamycin (n = 146) |

|

| Male sex, No. (%) | 85 (58) | 80 (55) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 47 (12.6) | 47 (12.7) |

| Causative organism, No. (%) | ||

| Fusarium species | 62 (42) | 53 (36) |

| Aspergillus species | 26 (18) | 23 (16) |

| Other | 58 (40) | 70 (48) |

| BSCVA, mean (SD), logMAR [Snellen equivalent] |

||

| Affected eye | 0.70 (0.38) [20/100] |

0.70 (0.39) [20/100] |

| Unaffected eye | 0.04 (0.18) [20/25] |

0.06 (0.20) [20/25] |

| Infiltrate size, mean (SD),b mm | 3.4 (1.15) | 3.3 (1.23) |

Abbreviations: BSCVA, best spectacle–corrected visual acuity; IND-VFQ, Indian Vision Function Questionnaire.

The t test was used to analyze continuous variables, and the Fisher exact test was used to analyze binary outcome variables.

Geometric mean of the longest diameter and longest perpendicular diameter.

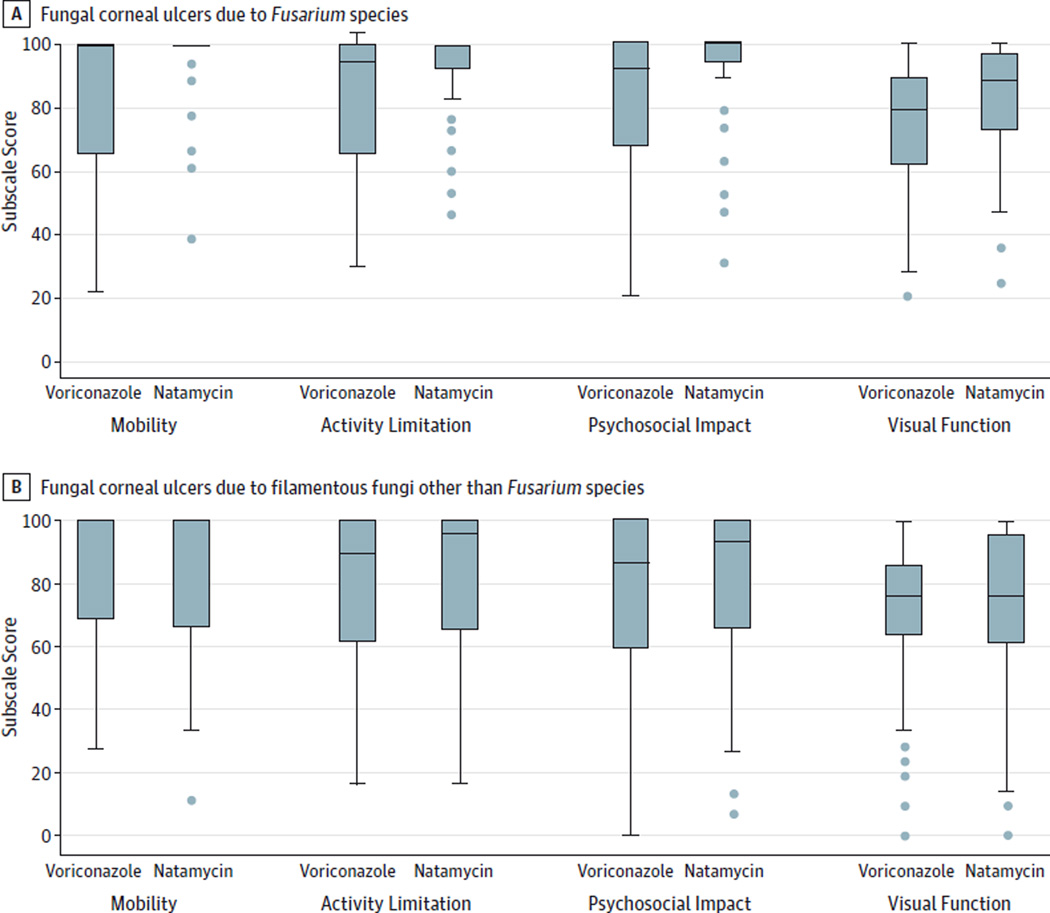

The majority of study participants had raw subscale scores consistent with excellent function at 3 months. Raw scores on the mobility scale were very high, with a median score of 100 (interquartile range [IQR], 69–100). The activity limitation subscale score (median score, 97 [IQR, 73–100]) and the psychosocial impact subscale score (median score, 93 [IQR, 67–100]) were good, whereas the visual function subscale score was decreased overall compared with the other 3 subscales (median score, 76 [IQR, 62–91]). The Figure demonstrates raw subscale scores by treatment arm for all ulcers due to non-Fusarium species compared with ulcers due to Fusarium species.

Figure. IND-VFQ Subscale Scores by Treatment Arm.

The horizontal line in each box indicates the median, while the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers above and below the box mark the 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively. The points beyond the whiskers are outliers beyond the 10th percentile. IND-VFQ indicates Indian Vision Function Questionnaire.

Table 2 outlines the difference in IND-VFQ scores by type of organism. When analyzing all the different types of ulcers, we found that the natamycin-treated group scored, on average, about 4.3 points (95% CI, 0.1–8.5; P = .046) higher on the IND-VFQ than the voriconazole-treated group after correcting for organism (Fusarium vs non-Fusarium species) and baseline visual acuity. In subgroup analyses looking at ulcers due to Fusarium species only, the natamycin-treated group scored 8.4 points (95% CI, 1.9–14.9; P = .01) higher on the IND-VFQ than the voriconazole-treated group after adjusting for baseline BSCVA. In contrast, among the ulcers due to non-Fusarium species, a difference between the 2 treatment groups was not detected; the natamycin-treated group scored 1.5 points (95% CI, −3.9 to 6.9; P = .52) higher than the voriconazole-treated group after correcting for baseline BSCVA. Study participants in the natamycin-treated group with an ulcer due to Aspergillus species scored 3.3 points higher on the IND-VFQ after correcting for BSCVA; however, this was also not statistically significant (95% CI, −9.1 to 15.7; P = .60). Between the treatment groups, differences in quality of life were also not detected for participants with ulcers that were due to an organism other than Fusarium or Aspergillus species; natamycin-treated participants scored an average of 0.5 points (95% CI,−5.4 to 6.4; P = .86) higher.

Table 2.

Difference in IND-VFQ Subscale Scores, by Type of Ulcera

| Type of Ulcer | Difference in Score, Mean (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|

| All ulcers | 4.3 (0.1–8.5) | .046 |

| Ulcers due to Fusarium species | 8.4 (1.9–14.9) | .01 |

| Ulcers due to Aspergillus species | 3.3 (−9.1 to 15.7) | .60 |

| Ulcers due to non-Fusarium species | 1.5 (−3.9 to 6.9) | .52 |

Abbreviation: IND-VFQ, Indian Vision Function Questionnaire.

Values calculated from a generalized estimating equation comparing average subscale scores between treatment groups, allowing for clustering (nonindependence of outcomes) of within-patient subscale scores and adjusted for baseline best spectacle–corrected visual acuity and organism (Fusarium vs non-Fusarium). Models for organism-specific subgroups were not adjusted for organism. Positive values indicate higher visual functioning in the natamycin-treated group; negative values indicate higher visual functioning in the voriconazole-treated group.

Discussion

Among patients with filamentous fungal ulcers, we found evidence of higher vision-related quality of life for those who were treated with natamycin than for those who were treated with voriconazole. This difference was more pronounced among participants with a corneal ulcer due to Fusarium species. Although these differences in the IND-VFQ subscale score were relatively small, it is noteworthy that we were able to detect a difference at all, given that the 3-month visual acuity was good (median visual acuity, 0.23 logMAR [IQR, 0.07–0.58 logMAR]; median Snellen equivalent, 20/30) and that the scores overall were high. In developed countries, where the ability to read or drive is integral to life, even a mild decrease in visual acuity results in a significant decline on a visual function questionnaire.16 It is possible that, in developing countries, mild vision loss does not decrease daily function until it has progressed considerably. The differences between treatment arms in IND-VFQ scores among participants with an ulcer due to Fusarium species were much larger. These findings are consistent with the primary out come from the trial, which found that 3-month BSCVA was better in the natamycin-treated group than in the voriconazole-treated group, with the difference between treatment groups attributable primarily to the ulcers due to Fusarium species.

The US Food and Drug Administration and the NEI now recommend that visual function questionnaires be used to evaluate interventions in ophthalmology. In previous studies in which the NEI Visual Function Questionnaire was used in developing countries, some of the questions did not test well because of cultural differences or lack of relevance (eg, the effect of visual disability on driving).6 To accurately measure outcomes, the questions need to be adapted to the culture and language in which the questionnaire is administered. Our questionnaire was the best instrument available at the time; it was developed in the local language with culturally relevant questions and has been validated and refined by Rasch analysis in a population of Indian patients.

Although our results were statistically significant, clinically meaningful changes on the IND-VFQ have not yet been determined. The NEI Visual Function Questionnaire is scored similarly to the IND-VFQ and has been better studied in this regard. One recent article17 evaluating the responsiveness of the NEI Visual Function Questionnaire to visual acuity changes concluded that a 4-point change in the overall VFQ score or a 5-point change in an individual subscale score corresponded to a small, clinically significant change. Using this as a guide, we found that the difference between the natamycin- and voriconazole- treated groups (4.3 points) may indeed be clinically meaningful. Further work needs to be done to better understand what constitutes a clinically meaningful change on the IND-VFQ.

There are several limitations to our study. Although the IND-VFQ was developed and validated locally, it is difficult for any visual function questionnaire to fully characterize the disability associated with decreased vision. Moreover, the IND-VFQ was validated in patients with cataract, whose vision loss may be different from the monocular vision loss typically experienced by patients with a corneal ulcer. We did not collect quality-of-life data at the trial’s base line, which could have been informative. We also did not assess the effect of socioeconomic factors on vision-related quality of life. This trial was conducted for a population in rural southern India, and therefore these results may not be generalizable to other settings, particularly larger cities or more developed regions.

Conclusions

Our study is consistent with the finding from the MUTT I that natamycin is superior to voriconazole for the treatment of filamentous fungal corneal ulcers, and it underscores the importance of appropriate treatment of fungal keratitis. Incorporation of quality-of-life measures in clinical trials is important to fully evaluate the effect of the studied interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The research portion of our study was financially supported by the NEI, in conjunction with the NEI-sponsored MUTT I (grant U10-EY018573-01A1 to Dr Lietman, principal investigator).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funder/sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Group Information

Clinical Centers: Aravind Eye Hospital, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India: N. Venkatesh Prajna, MD (principal investigator), Prajna Lalitha, MD, Jeena Mascarenhas, MD, Muthiah Srinivasan, MD, FRCOphth, MA, Rajarathinam Karpagam, Malaiyandi Rajkumar, S. R. Sumithra, C. Sundar; Aravind Eye Hospital, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India: Revathi Rajaraman, MD (site director), Anita Raghavan, MD, P. Manikandan, MPhil; Aravind Eye Hospital, Pondicherry, Tamil Nadu, India: K. Tiruvengada Krishnan, MD (site director), N. Shivananda; Francis I. Proctor Foundation, University of California, San Francisco: Thomas M. Lietman, MD (principal investigator), Nisha R. Acharya, MD, MS (principal investigator), Stephen D. McLeod, MD, John P. Whitcher, MD, MPH, Salena Lee, OD, Vicky Cevallos, MT(ASCP), Brett L. Shapiro, MD, Catherine E. Oldenburg, MPH, Kieran S. O’Brien, MPH, Kevin C. Hong, BA. Data and Safety Monitoring Committee: Marian Fisher, PhD (chair), Anthony Aldave, MD, Donald Everett, MA, Jacqueline Glover, PhD, K. Ananda Kannan, MD, Steven Kymes, PhD, and Ivan Schwab, MD. Resource Centers: Coordinating Center, Francis I. Proctor Foundation, University of California, San Francisco: Thomas M. Lietman, MD (principal investigator), Nisha R. Acharya, MD, MS (principal investigator), David Glidden, PhD, Stephen D. McLeod, MD, John P. Whitcher, MD, MPH, Salena Lee, OD, Kathryn Ray, MA, Vicky Cevallos, MT (ASCP), Brett L. Shapiro, MD, Catherine E. Oldenburg, MPH, Kevin C. Hong, BA, Kieran S. O’Brien, MPH; Project Office, NEI, Rockville, Maryland: Donald F. Everett, MA; Photography Reading Center, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire: Michael E. Zegans, MD, and ChristineM. Kidd, PhD.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Keenan and Rose-Nussbaumer had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Prajna, Krishnan, Srinivasan, Oldenburg, McLeod, Lietman, Acharya.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Rose-Nussbaumer, Mascarenhas, Rajaraman, Raghavan, Oldenburg, O’Brien, Ray, Porco, Acharya, Keenan.

Drafting of the manuscript: Rose-Nussbaumer.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Rose-Nussbaumer, Prajna, Srinivasan, Ray, Porco, Keenan.

Obtained funding: Oldenburg, Acharya.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Krishnan, Mascarenhas, Rajaraman, Raghavan, Oldenburg, O’Brien, McLeod, Lietman, Acharya.

Study supervision: Lietman, Acharya.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and Ms O’Brien reports having received grants from the NEI during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Varma R, Richman EA, Ferris FL, III, Bressler NM. Use of patient-reported outcomes in medical product development: a report from the 2009 NEI/FDA Clinical Trial Endpoints Symposium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(12):6095–6103. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nassiri N, Mehravaran S, Nouri-Mahdavi K, Coleman AL. National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire: usefulness in glaucoma. OptomVis Sci. 2013;90(8):745–753. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khadka J, McAlinden C, Pesudovs K. Validation of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire25 (NEI VFQ25) in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(3):1276. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein R, Moss SE, Klein BE, Gutierrez P, Mangione CM. The NEI-VFQ-25 in people with long-term type 1 diabetes mellitus: the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(5):733–740. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marella M, Pesudovs K, Keeffe JE, O’Connor PM, Rees G, Lamoureux EL. The psychometric validity of the NEI VFQ-25 for use in a low-vision population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(6):2878–2884. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qian Y, Glaser T, Esterberg E, Acharya NR. Depression and visual functioning in patients with ocular inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(2):370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitale S, Goodman LA, Reed GF, Smith JA. Comparison of the NEI-VFQ and OSDI questionnaires in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome-related dry eye. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:44. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orr P, Rentz AM, Margolis MK, et al. Validation of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (NEI VFQ-25) in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(6):3354–3359. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cusick M, SanGiovanni JP, Chew EY, et al. Central visual function and the NEI-VFQ-25 near and distance activities subscale scores in people with type 1 and 2 diabetes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(6):1042–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta SK, Viswanath K, Thulasiraj RD, et al. The development of the Indian vision function questionnaire: field testing and psychometric evaluation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(5):621–627. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Thulasiraj RD, Viswanath K, Donoghue EM, Fletcher AE. The development of the Indian vision function questionnaire: questionnaire content. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(4):498–503. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.047217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finger RP, Kupitz DG, Holz FG, et al. The impact of the severity of vision loss on vision-related quality of life in India: an evaluation of the IND-VFQ-33. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(9):6081–6088. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick KD, Drye LT, Kempen JH, et al. Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment-MUST Trial Research Group. Associations among visual acuity and vision - and health-related quality of life among patients in the multicenter uveitis steroid treatment trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(3):1169–1176. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Hong J, Wei A, et al. Vision-related quality of life in patients with infectious keratitis. OptomVis Sci. 2014;91(3):278–283. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, et al. Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. Themycotic ulcer treatment trial: a randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(4):422–429. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finger RP, Fenwick E, Marella M, et al. The impact of vision impairment on vision-specific quality of life in Germany. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(6):3613–3619. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-7127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Submacular Surgery Trials Research Group. Evaluation of minimum clinically meaningful changes in scores on the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ) SST Report Number 19. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14(4):205–215. doi: 10.1080/09286580701502970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.