Abstract

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP) is a rare histological subset of pyelonephritis characterized by being a chronic destructive granulomatous inflammation of the renal parenchyma. XGP is classified according to the extent of disease into two entities: within the renal cortex (focal or segmental XGP) or diffuse spread with pelvic communication (diffuse XGP). Although rare, XGP can have fatal complications including perinephric, psoas abscess, nephro-cutaneous fistula and reno-colic fistula. Only few studies have reported XGP complicated with psaos abcess and reno-colic fistula. Our aim is to add to the literature and share our experience with a case of extensive XGP eroding into the psoas muscle and ascending colon leading to severe sepsis that was successfully managed. We report a 56-year-old woman who was found to have XGP complicated by psoas abscess and reno-colic fistula managed by antibiotics, nephrostomy, and subsequent nephrectomy and partial colectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are considered to be the most common bacterial infections in the united states with nearly 7 million office visits and 1 million emergency department visits, resulting in approximately 100 000 hospitalizations per year [1]. Pyelonephritis is a common complication of untreated UTIs, however Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP) is a rare histological subset, which accounts for only 0.6% of histologically documented cases of chronic pyelonephritis [2]. Diffuse XGP can spread into the pelvic cavity leading to fatal complications including emphysematous pyelonephritis, perinephric abscess, psoas muscle abscess, nephro-cutaneous fistula, nephro-colonic fistula and can even lead to ischemic colitis secondary to large mass compression [3]. The rarity of XGP together with the obscure presenting symptoms of its associated complications pose a great diagnostic challenge for physicians, leading to delayed treatment and an adverse influence on the morbidity and mortality rates.

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old woman with a medical history of Type 2 miabetes mellitus, lymphedema, appendectomy, cholecystectomy and no known gastrointestinal disease was initially admitted with nausea, vomiting and altered mental status. The patient had an elevated white blood cell count (WBC) of 18 000/uL (range 4500–11 000/uL), lactic acid of 2.7 mmol/L (range 0.5–2.2 mmol/L) and creatinine of 0.9 mg/dL (range 0.5–1.1 mg/dL). A work up for identifying a septic focus was only significant for a urine analysis suggestive for a UTI (WBCs > 100 cells/high power field and a positive leukocyte esterase test). Urine culture grew cephalosporins sensitive Escherichia coli and Klebsiella oxytoca. The patient received a 5-day course of ceftriaxone and was subsequently discharged when levels of WBC and lactic acid normalized.

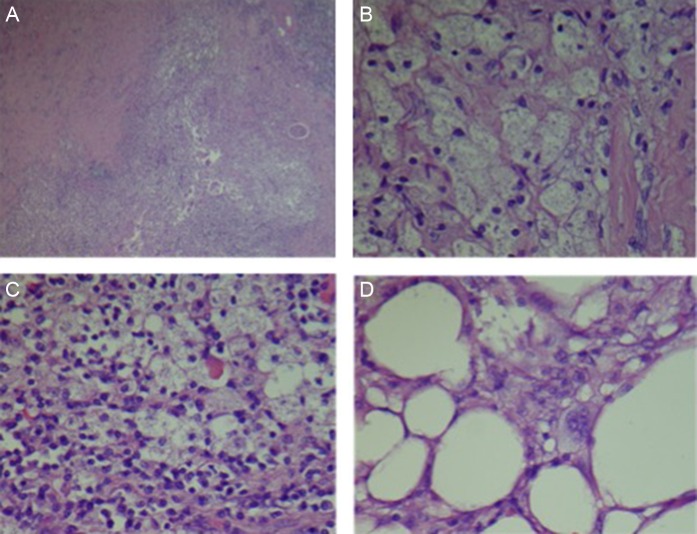

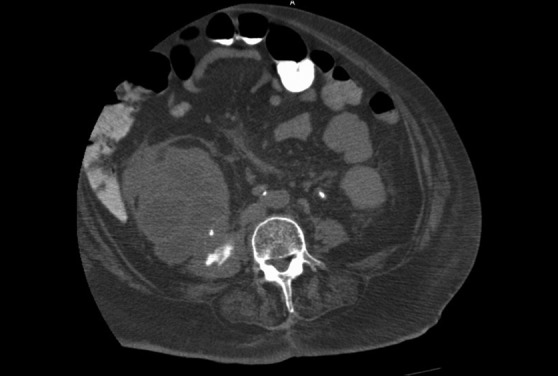

After 22 days, the patient was readmitted with diffuse abdominal pain. The patient was in septic shock with a blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg, elevated WBC of 21 000/uL, lipase of 941 U/L and hemoglobin and hematocrit of 11.3 g/dlL (range 11–16 g/dL) and 36.8% (range 33.5–45%), respectively. Computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous and oral contrast was ordered and revealed a right-sided renal obstructing stone (staghorn), enlarged right kidney with multiple low-attenuation cytic lesions and a perinephric fluid collection that communicates with the colon and the right psoas muscle (Figs. 1 and 2). CT scan findings are characteristic for XGP and referred to as the ‘bear's paw sign’ [4] (Fig. 3). Urine culture was repeated and grew Morganella morganii species. Subsequently, the patient underwent a successful placement of a percutaneous nephrostomy and purulent fluid was drained which grew similar organism to the one that grew in the urine. Nephrostogram was performed and showed extravasations into the psoas muscle and communication with the ascending colon. Seven days later, the patient underwent open right nephrectomy, right partial colectomy and drainage of the psoas abscess. Grossly, the kidney was distorted with multiple cavitated lesions filled with cheesy like content in the renal cortex, extending to the peri-renal and adipose tissue. Renal calyces were markedly dilated (6.5 cm) with a 3 × 1.5 cm staghorn calculus. Pathology slides are presented in Fig. 4. No malignant cellular changes were identified in the resected tissues excluding renal cell carcinoma. Resected colon did not show any inflammatory or malignant changes. The patient recuperated well and the final most probable diagnosis is XGP complicated by psoas abscess eroding into the bowel resulting in a reno-colic fistula resulting in septic shock.

Figure 1:

Enhanced axial CT image showing a perinephric fluid collection and the reno-colic fistula (Black arrow).

Figure 2:

Enhanced axial CT image at the level of the mid right kidney reveals a centrally obstructing stone with replacement of the renal parenchyma by hypoattenuating collections in a hydronephrotic pattern. This pattern is referred to as the ‘Bear's paw’ sign.

Figure 3:

Enhanced axial CT image showing right psoas muscle abscess.

Figure 4:

(A) Low poor view of altered, atrophic and sclerosed renal parenchyma with histiocytic localized inflammation. (B) High power view of foamy histiocytes (xanthomatous cells). (C) Mixed xanthomatous and chronic inflammatory infiltrate. (D) Xanthomatous infiltration of perinephric adipose tissue.

DISCUSSION

XGP is a rare chronic destructive granulomatous process of the renal parenchyma, which was first described by Schlagenhaufer in 1916 [5]. Incidence is more common in females usually during the fifth and sixth decades of life. Symptoms typically include flank or abdominal pain along with fever, gross hematuria and weight loss. XGP is often associated with obstructive urolithiasis with around 34.1% of the cases in literature were found to have staghorn calculi [5]. Although, XGP is defined as being a localized process involving the renal parenchyma (Stage I), resultant inflammation can spread to involve the perinephric fat (Stage II) and can even spread further to involve the perinephric and paranephric spaces forming perinephric and/or psoas muscle abscesses (Stage III), as proposed by a relatively new staging system by Malek et al. [6]. A more commonly used radiological classification stratified XGP into two forms, a diffuse form which comprises 85% of the cases and a focal (localized, segmental) form comprising 15% of cases [7]. Besides abscesses formation, other rare complications were reported that included reno-cutaneous fistulas, reno-colonic fistulas and reno-bronchial fistula [3,8]. The definite diagnosis of XGP is by renal biopsy showing lipid-containing foam cells (xanthoma cells), however CT scan is the best non-invasive diagnostic modality to aid towards the diagnosis. Management of XGP depends on the extent of disease. In diffuse or advanced stage XGP, nephrectomy is the ultimate treatment option, while focal or segmental XGP if diagnosed early pre-operatively can be treated with antibiotics. Pre- and post-operative broad spectrum antibiotics and symptomatic management are also key factors for successful management and better prognosis. A study by Kuo et al. had studied some risk factors that can aid in an early pre-operative diagnosis that included age, sex, renal calculi and central obesity and suggested that maintaining a high index of suspicion for XGP should lead to improvements in the pre- operative diagnostic rate [9].

Our case has met most of the criteria of the early pre-operative diagnosis that helped us include XGP on top of our differential diagnosis. The patient was in the age group and gender that were described to be more suggestive for XGP along with the presence of a staghorn calculus and the ‘Bear's paw’ sign on CT scan. The infectious micro-organism in our case was M. morganii, a Gram-negative bacteria found in the intestinal tracts of humans and is a common cause for UTIs but has also been previously described in intra-abdominal infection. The presence of the reno-colic fistula might have facilitated the spread of the organism between the colon and kidneys. Nephrostogram was used to aid in understanding the anatomy of the fistulas detected by the CT scan. We have performed an initial nephrostomy for decompression and evacuation as part of managing sepsis, and patient has clinically improved afterwards. Given the diffuse nature of the disease, nephrectomy was the ultimate treatment of choice with surgical evacuation of the psoas abscess and partial colectomy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Patient has verbally accepted using her health care information for publication.

CONSENT

Patient signed a research consent form.

GUARANTOR

Abdulrahman Babeir, Nicholas James and Hassan Ghoz.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Ghazo MA, Ghalayini IF, Matalka II, Al-Kaisi NS, Khader YS.. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: analysis of 18 cases. Asian J Surg 2006;29:257–61. doi:10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Am J Med 2002;113:5S–13S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harikrishnan JA, Hall TC, Hawkyard SJ.. Nephrobronchial fistula. A case report and review of the literature. Cent European J Urol 2011;64:50–1. doi:10.5173/ceju.2011.01. art12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korkes F, Favoretto RL, Broglio M, Silva CA, Castro MG, Perez MD.. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: clinical experience with 41 cases. Urology 2008;71:178–80. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo CC, Wu CF, Huang CC, Lee YJ, Lin WC, Tsai CW, et al. . Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: critical analysis of 30 patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2011;43:15–22. doi:10.1007/s11255-010-9778-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malek RS, Elder JS.. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: a critical analysis of 26 cases and of the literature. J Urol 1978;119:589–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malek RS, Greene LF, DeWeerd JH, Farrow GM.. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Br J Urol 1972;44:296–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segovis CM, Dyer RB.. The “bear paw” sign. Abdom Imaging 2015;40:2049–50. doi:10.1007/s00261-015-0358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zorzos I, Moutzouris V, Korakianitis G, Katsou G.. Analysis of 39 cases of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis with emphasis on CT findings. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2003;37:342–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]