Abstract

HIV-seroconversion during pregnancy is a serious concern throughout South Africa, where an estimated 35 to 40% of pregnant women have HIV/AIDS and drop-out is high at all stages of the prevention-of-mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT) process. The likelihood of PMTCT success may be linked to partner support, yet male involvement in antenatal care remains low. This qualitative study examined the influence of pregnant couples’ expectations, experiences and perceptions on sexual communication and male involvement in PMTCT. A total of 119 couples participated in a comprehensive intervention in 12 antenatal clinics throughout South Africa. Data were collected between December 2010 to June 2011 and analysed using a grounded theory approach. Findings point to the importance of sexual communication as a factor influencing PMTCT male involvement. Analysis of themes lends support to improving communication between couples, encouraging dialogue among men and increasing male involvement in PMTCT to bridge the gap between knowledge and sexual behaviour change.

Keywords: PMTCT, HIV, couples, sexual communication, disclosure

Introduction

Worldwide, the prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT) has played a central role in reducing HIV-related child mortality (Joseph 2004; Theuring et al. 2009). Although South Africa’s PMTCT effort is comprehensive, incorporating counselling, HIV-testing and antiretroviral prophylaxis for the mother and infant (Peltzer et al. 2011), transmission rates remain relatively high at between 12 and 20% (Department of Health 2009).

In South Africa, an estimated 35–40% of pregnant women have HIV/AIDS (Maman, Moodley, and Groves 2011) and drop-out is high at all stages of the PMTCT process (Department of Health 2009). An alarming number of babies born to HIV-positive mothers do not receive dual therapy – an estimated 30% of over 1 million babies born each year (Department of Health 2009). Mpumulanga Province, in rural north-eastern South Africa, has the highest reported HIV prevalence (4.5%) among children (0–18 years) (Shisana 2010) and is the second highest province in the country that continues to show evidence of continuous increases in HIV prevalence among antenatal clinic attendees, with rates from 29% in 2001 to 35% in 2010 (National Department of Health 2011). Reported rates of antenatal clinic (ANC) HIV prevalence in 2010 ranged from 27.2 to 38.9% in the Nkangala and Gert Sibande districts of Mpumulanga Province, respectively (National Department of Health 2011).

HIV-seroconversion during pregnancy is a serious concern throughout sub-Saharan Africa. A recent study of 3321 HIV-serodiscordant couples in seven countries, including South Africa, found the incidence of women seroconverting during pregnancy was higher than during non-pregnancy (i.e., 7.35 per 100, as compared to 3.01 per 100, respectively) –28% of the seroconversions among women occurred during pregnancy (Mugo et al. 2011). Among male partners of infected women, seroconversion was higher when their partner was pregnant (3.46 per 100) versus during non-pregnancy (1.58 per 100) (Mugo et al. 2011). In South Africa, the risk of seroconversion increases during pregnancy and is 29% (Hazard Ratio 1.65) for women 24 years of age or less and 22% (HR 1.85) for women 24–35 years of age (Wand and Ramjee 2011). These high seroconversion rates during pregnancy highlight the need for prevention at multiple levels in the PMTCT process – unless women are re-tested prior to delivery, HIV-seroconversion may remain undetected (Kinuthia et al. 2010).

As noted in the literature, self-disclosure of HIV-serostatus may be stressful and risky due to the potential ramifications (e.g., loss of financial support) (Mindry et al. 2011). Although potentially serving as a catalyst to engagement in treatment (Peltzer and Mlambo 2010), disclosure may be marred by stigma and rejection (Rispel et al. 2012; Ujiji et al. 2011 ; Wyrod 2011). The positive effects of disclosure, such as facilitating entry into care, may also be overshadowed by intimate partner violence (IPV), abandonment and rejection by loved ones and social discrimination (Peltzer and Mlambo 2010). A woman’s non-disclosure of her HIV-serostatus during pregnancy increases her partner’s HIV-risk, reduces her own engagement in medical treatment and antenatal care and, ultimately, places her child at risk of HIV transmission (Visser et al. 2008).

Incorporating male partners more fully into PMTCT programmes may facilitate their involvement in the antenatal HIV Counselling and Testing (HCT) process and enhance HIV disclosure among couples. It may also increase the uptake of PMTCT strategies and adoption of ARV prophylaxis by mothers and newborns (Auvinen, Suominen, and Valimaki 2010; Maman, Moodley, and Groves 2011; Peltzer et al. 2010). In addition, male involvement may reduce couples’ risk of HIV exposure during the vulnerable period of pregnancy and facilitate communication about HIV and the adoption of preventive behaviours (e.g., sexual barrier use, limiting sexual partners) (Mbonye et al. 2009; Peltzer, Mlambo, and Phaweni 2010). Increased communication may also break down some of the stigma and shame associated with HIV.

The likelihood of success of PMTCT in South Africa may in part be linked to male partner support, yet male involvement in antenatal care remains low (Maman, Moodley, and Groves 2011). As a prevention strategy, increasing male involvement during pregnancy has met with success in programmes throughout sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Agu 2009; Aluisio et al. 2011; Becker et al. 2010). The present study, PartnerPlus, was designed to evaluate the impact of male involvement on PMTCT uptake by utilising the existing public-health framework linking antenatal HCT and PMTCT services in South Africa. This article presents qualitative data on HIV disclosure, sexual negotiation and male involvement in PMTCT among pregnant women and their male partners who participated in gender-concordant group intervention sessions. The purpose of the study was to provide a greater, detailed and nuanced understanding of the couples’ experiences, which could inform the development and implementation of integrated PMTCT/sexual-risk-reduction interventions.

Methods

The PartnerPlus study is a comprehensive couples-based PMTCT intervention in rural South Africa. The intervention combines key elements of two evidence-based interventions, Partner Project, a couples’ behavioural HIV-risk reduction intervention (Jones et al. 2005, 2006, 2009), plus a medication-adherence intervention designed to enhance PMTCT uptake (Peltzer et al. 2011). A total of 12 ANCs in Mpumalanga province’s Gert Sibande and Nkangala districts were randomly assigned to receive the PartnerPlus intervention (Experimental) or usual care plus a time-matched health education session (Control). Participants were pregnant women over the age of 18 years who completed HCT and were between 24 to 30 weeks pregnant. Women enrolled as couples with their male partners (n = 119 couples) from December 2010 to June 2011. Participants were screened to verify their status as primary sexual partners and both partners provided informed consent.

Intervention

The PartnerPlus intervention employed closed, structured, gender-concordant groups limited to 10 participants per group. The intervention consisted of four weekly, 90- to 120-minute group sessions, which were led by two trained lay counsellors. The sessions emphasised cognitive-behavioural skills building to improve communication and sexual risk reduction (Peltzer et al. 2011). Participants in the control condition received the standard of care (PMTCT) and attended four time-matched group sessions during which they viewed educational videos that addressed aspects of healthy living (e.g., nutrition, exercise). All participants received the PMTCT standard of care prevailing at the ANCs in Mpumulanga province.

The University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB-US), Human Sciences Research Council Research Ethics Committee (HSRC-REC-SA) and Mpumalanga Provincial Department of Health approvals were obtained prior to the onset of the study.

Data collection

Demographics

Details of age, educational level, employment status, household and personal income, residential status, ethnicity, HIV status, HIV partner status, marital status and cohabitation status were collected. HIV serostatus was obtained from clinic records.

Qualitative data

The qualitative data presented were transcribed and translated from local languages (Zulu, Ndebele and Sepedi) to English from audio recordings of gender-concordant group intervention sessions led by lay counsellors. Participants were not asked to disclose their HIV-status, though some openly disclosed in the course of group discussions. Emphasizing cognitive-behavioural skills building to improve communication and sexual-risk-reduction strategies, the sessions led to discussions on sexual-health-related topics, some of which ultimately became core themes. These themes were derived from major issues that were addressed during the intervention. Throughout the sessions, open-ended grand tour questions were asked to solicit thoughts and feelings on sexual health. Using grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967), specific themes were identified through the review process and, once they reached the point of data saturation, some became prominent and were labelled as ‘core themes’. To improve external validation, several manuscript authors cross-checked 40% of the qualitative data, reaching 80% agreement, and reconciled the remaining themes. Themes that did not reach saturation were not deemed prominent (i.e., saturation cut off < 30%) and were not selected for discussion in this study (e.g., breastfeeding, IPV, medication adherence, traditional healing).

Results

Participant characteristics

Couples’ (n = 119) characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age for women was 26.1 years (range 18–41) and 30.5 for men (range 19–52). The majority of participants were of Zulu (n = 83, 35%), Ndebele (n = 65, 27%) and Sepedi (n = 50, 21%) ethnicity. An average of 17% (n = 40) of participants belonged to other ethnic groups, such as Northern Sotho and Swati. Most participants (n = 156, 66%) lived in rural areas and were unemployed (Women: n = 77, 65%; Men: n = 70, 59%). Participants described their marital status as never married (n = 177, 75%) and married (n = 27, 11%). The majority of participants were not living with their sexual partner (n = 204, 86%; cohabitating, n = 34, 14%).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline.

| Variable | Women n(%) (n = 119) | Men n(%) (n = 119) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean: 26.08 (SD = 5.83) | Mean: 30.54 (SD = 7.05) |

| Range = 18–41 | Range = 19–52 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Zulu | 42 (35.3) | 41 (34.5) |

| Ndebele | 32 (26.9) | 33 (27.7) |

| Sepedi | 25 (21.0) | 25 (21.0) |

| Other | 20 (16.8) | 20 (16.8) |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 78 (65.5) | 78 (65.5) |

| Urban | 41 (34.5) | 41 (34.5) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 14 (11.8) | 13 (10.9) |

| Never married | 89 (74.8) | 88 (73.9) |

| Cohabitation status | ||

| Living with partner | 16 (13.4) | 18 (15.1) |

| Not living with partner | 103 (86.6) | 101 (84.9) |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 18 (15.1) | 45 (37.9) |

| Unemployed | 77 (64.7) | 70 (58.8) |

| Student/learner | 4 (3.4) | 2 (1.7) |

| HIV-positive | 37 (31.1) | 13 (14.4) |

| Education level | Grade 7 or less: 7 (5.8) | Grade 7 or less: 8 (6.7) |

| Grade 8–11: 68 (57.2) | Grade 8–11: 52 (43.7) | |

| Grade 12 or more: 44 (37.0) | Grade 12 or more: 59 (49.5) | |

| Number of children | ||

| Zero | 47 (39.5) | 51 (42.9) |

| One | 46 (38.7) | 36 (30.3) |

| Two | 14 (11.8) | 18 (15.1) |

| Three | 9 (7.6) | 11 (9.2) |

| Four/+ | 3 (2.5) | 3 (2.5) |

| Range = 1–4 | Range = 1–6 | |

| Attendance | ||

| Session 3 | 92 (77.3) | 92 (77.3) |

| Session 4 | 88 (73.9) | 86 (72.3) |

Core themes

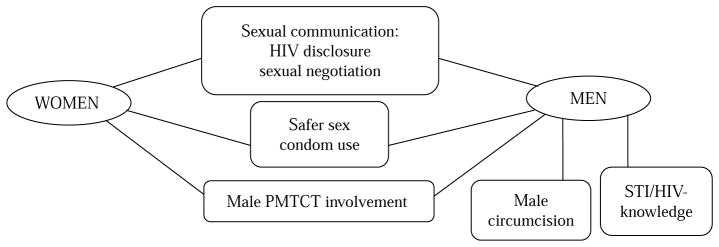

Core themes are presented by gender to differentiate gender-specific themes from those that were of equal importance to both sexes. The core themes identified from the women’s sessions were HIV disclosure and sexual negotiation, safer sex and male involvement. The same core themes were identified from the men’s sessions, in addition to STI/HIV-related knowledge and male circumcision. The statements are drawn from group intervention discussions by study participants (see Figure 1). All of the names provided are fictitious.

Figure 1.

Core themes by gender.

HIV disclosure and sexual negotiation

Women

Disclosure of HIV-serostatus and sexual negotiation within the couple became central themes for the women. Sub-themes were also identified, including issues related to trust and benefits associated with disclosure. Trust, especially as it related to supportive and caring relationships, was interconnected with HIV disclosure:

I believe disclosure is good but if you disclose your status to someone you trust and believe they will not tell anyone and the person must be there for you to give you the support you need when you need it.

(Jess, age 22)

Women provided positive perspectives on the benefits of HIV disclosure. For instance, disclosing HIV serostatus to a partner may increase encouragement and support to attend medical appointments and adherence to treatment and medication regimens. Another potential benefit was that it may serve as a catalyst for the partner to be tested for HIV and receive treatment.

A recurring misconception regarding HIV testing was discussed during the sessions, whereby it was believed that if one person in the couple was tested for HIV, regardless of the result, the other partner did not have to be tested since his/her result would be the same as the partner who was tested:

They [men] have this theory that if I have tested and I got my results then it means that their results are the same as mine.

(Faith, age 31)

Misconceptions were addressed by lay counsellors in all of the group sessions.

Women were sensitive to non-disclosure by their partners. When presented with a role-play scenario of a male partner who was tested for HIV and did not disclose his status, women reported that they would interpret his lack of disclosure as a silent admission of a positive HIV result. One woman stated:

I would think he wants to re-infect me or he wants to spread the disease to other women.

(Gladys, age 25)

Others provided similar responses, indicating that his silence would be ‘hurtful’ and evidence that he did not trust her. Numerous women asserted that if a partner did not disclose his status, they would leave the relationship for fear that he tested HIV-positive. Others responded with a sense of commitment, by remaining in the relationship and providing support.

Women recognised the value of effective communication in a relationship, although most felt that communication was hindered by both partners. While women valued communicating with their partners, they expressed concern over their ability to communicate adequately due to mutual anger or inappropriate expression of emotions:

The reason we talk like we do is that we do it in anger. If we calm down before talking we could avoid fighting.

(Jewel, age 33)

Other women expressed concern over communicating with their partners while they were intoxicated, for fear of physical or emotional abuse. Yet, women expressed the desire to communicate openly with their partners. One woman modelled for the group communication strategies that had been efficacious:

You have to ask them how do they feel. You should not guess how they feel or what will he say.

(Fikile, age 35)

Overall, women acknowledged they viewed themselves as helpless due to their perceived inability to communicate within their sexual relationships and recognised this was a barrier to openly expressing their concerns about HIV.

Men

Similar to their partners, men were also concerned with sexual negotiation and HIV disclosure, and sub-themes also included trust and benefits. One particular difference was that men perceived HIV-disclosure as a way to unburden themselves:

[Disclosing] is a right thing to do, most especially when you disclose to a person you trust and believe is worth telling because disclosing is a very sensitive issue but it has its own benefits in terms of making you feel free from stress.

(Bongani, age 41)

Discussions of trust and communication brought about intense emotional reactions and protracted discussions among men:

We should in a way try not to coerce our partners to have any reasons for wanting to interrogate us or even doubt us by making them trust us and making them feel they are of great importance to us as their partners.

(Tebocho, age 29)

Men also openly discussed how they negatively perceived women’s communication styles. In particular, men placed much of their focus on describing their negative perceptions of women, including generalisations such as ‘women hold grudges for long periods of time’. Some men also described women as too eager to share their personal problems with others outside of the couple, such as a friend or her mother. Men reported that this led to feeling betrayed. Other men felt women were emotionally labile, especially during pregnancy, and found them to be particularly difficult to communicate with during pregnancy due to their varying mood states.

Men were able to acknowledge the benefits associated with learning new communication skills and applying them to real-world relationships. Some offered examples of how the intervention successfully changed their ability to communicate within their relationships:

The way we used to handle our arguing has changed and we now both know how to start and finish an argument without having to bring out the old arguments.

(Charles, age 36)

I also have seen a big change between me and my partner because I have learned to listen to her and reply to her with the necessary respect she deserves. What I learned is that I have to describe my emotions to her so that she can know how I am feeling.

(Molefe, age 31)

Others described how opening the lines of communication with their partner had led to changes in sexual health behaviour:

We have improved a lot and we have even started using condoms.

(Mpho, age 27)

Others found it improved their ability to appropriately deal with anger and relieve stress:

[Communication] liberates you as a person…you don’t have stress where you will end up being depressed.

(Thema, age 44)

Talking things through with my partner really helps. If there is something bothering me and I talk about it with my partner I feel free – relieved, instead of keeping it to myself, because then I will have a lot of anger inside.

(Monde, 31)

Incorporating such key elements of effective communication enhanced the relationships. In addition, some men saw the value in providing the same intervention to both partners in the couple:

We both came here to learn as much as we would possibly learn and that has helped because whenever one of us forgotten what we learned the other partner is there to remind them.

(Thabo, age 38)

Safer sex and condom use

Women

Women’s discussions focused heavily on safer sex and condom use. Sub-themes included condom quality and efficacy, preference and men’s reactions to condom use. Women openly discussed preconceptions, experiences and partner reactions.

The majority of women described male condoms in negative terms. In particular, women did not find sex to be as pleasurable with a male condom, while some indicated having sex with a man who was using a male condom was ‘painful’. Yet, these negative reactions did not overshadow the importance of condom use. As the intervention reinforced the use of condoms during pregnancy, one woman echoed what so many other women learned about protecting oneself during pregnancy:

I now know that even if you are pregnant it is of high importance to continue using condoms for the sake of me and my partner and the safety of the unborn child.

(Gugu, age 20)

In general, female condoms elicited more interest than the male condom. In fact, women made more positive associations with female condoms. Advantages to using female condoms included the fact that use was under a woman’s control and that female condoms were convenient because they could be worn prior to engaging in sexual intercourse:

If your partner does not want to use the male condom, then you could the female condom because he would find you wearing it already.

(Neo, age 23)

I liked it because I am the one putting it on unlike the male condom because it is him who has to put it on and when he does not want to he may not use it and there is nothing I can do about it.

(Florence, age 31)

Men can easily cheat us with theirs [male condoms]. They prick them. You think you are protected while he knows exactly what he did. So I like the female ones.

(Ntombi, age 28)

For women, having control seemed to outweigh any negative associations regarding female condoms.

When asked if they would encourage other women to use female condoms, the responses were overwhelmingly positive. The majority of women reported they were able to overcome the initial uncertainty associated with first-time exposure to the female condom and would encourage other women to continue practicing before giving up on using it. Those women, who still had not become accustomed to them, insisted they would continue practising with them.

Despite overall optimism, difficulties associated with the female condom were identified, such as the added effort it takes to properly insert, which could impede sex:

It takes forever [to insert] because there is unplanned sex; there will not be enough time to insert the female condom. The kind of sex that I am talking about is the kind where you do not plan. Let us say you with your partner and you are watching a movie and there is a moment where the two of you start kissing and touching and from there you throw each other on the bed and sex takes place. There will not be time for inserting the female condom.

(Mary, age 24)

When asked about partner reactions to female condom use, responses were both positive and negative:

He liked it [sex with female condom], but at first he had doubts that he would enjoy himself.

(Edith, age 35)

Others indicated that their partner simply refused to use the female condom without having tried it:

We did not use it. He just looked at it and said it was too big, but I hope with time he will agree just to try it.

(Betty, age 22)

Regardless of partner reaction, there was an overwhelming response from women that they would continue using female condoms.

However, the majority of women expressed apprehension in engaging in sexual barrier negotiations with their partner. Women were given a role-play scenario where they were provided with condoms at a clinic and asked how they would discuss condom use with their partner. For most women, their perception of their partners’ reaction was negative:

The first thing he will say is, ‘I do not use these things [condoms].…Don’t get crazy on me with your people from the clinic’.

(Irene, age 31)

Although, some rationalised that their partner would be more open to the suggestion of condom use if it was done to protect their baby:

I will tell him if he loves this baby he will listen and understand the reasons. This is not because I am having funny thoughts about you it’s just that it is important to have safer sex. You are not only saving me but the child and yourself.

(Fanie, age 36)

The counsellor continued by asking the same woman: ‘Do you think your partner would accept it just like that?’ and she replied:

Well, knowing my partner he will not want us to use the condom but I would try my best to make him understand why it was important to use it in order for us to protect our unborn child.

(Fanie, age 36)

Interestingly, condom use was perceived as an act of protection that is acceptable during the beginning stage of a relationship:

Men tend to believe that you use the condom when the relationship is still new. Once you have been together for some time, they want to stop…it [condom use] cannot be forever with men.

(Ruth, age 28)

Women were asked to share how they would feel if their partner was not agreeable to using condoms. Many of the responses included embarrassment, feeling unappreciated and worthless. One woman, in particular, addressed the challenge of overcoming her apprehension and how she would feel if her partner reacted negatively:

…bad, because obviously it would have not been easy bringing them home [condoms] and for him to react that way would make me feel like I’ve done something wrong.

(Rose, age 34)

Women also described their own experiences when their partner became upset at the mention of condoms, accusing them of being unfaithful or insinuating that the request to use condoms was due to an irrational fear that he was having sexual relations with another woman. For some, the discomfort associated with discussing condom use with a partner was so intense that they refused to do so from the onset:

Most women keep quiet to avoid fighting because if he does not like something he will not do it, he may say ‘why should I use condom with you, I am your husband’ and if you try to explain he will end up making you feel that it is wrong to even raise the subject.

(Esther, age 36)

At the end of the day if he is not happy it ruins the relationship and he may even start looking for girls who would not mind sex without a condom.

(Elisa, age 25)

Internalised feelings of self-worth and perceived partner apathy also affect a woman’s ability to negotiate condom use.

Men

Men were candid in discussing condoms, their expectations, fears and experiences. Some expressed a clear understanding of the importance of using sexual protection during and after pregnancy, although when asked what they would think or feel if their partner came home with condoms and suggested they use them, men responded mostly negatively. Reactions ranged from assuming infidelity by his partner to his partner not trusting him. Misconceptions and cultural beliefs also impacted condom use:

I don’t think it’s a good idea to use a condom while my partner is pregnant. I won’t be able to feed my partner with sperms so the baby can be healthy.

(Jeffrey, age 20)

Similar to male condoms, men held strong feelings in regards to female condoms. These reactions primarily focused on product characteristics, such as difficulty using the product:

It was not a good experience. It was difficult for her to insert it herself. I had to do it myself and while we had sex I could hear sounds coming from the condom.

(Kenneth, age 31)

Other negative reactions associated with female condoms included that they took too much time to insert properly, which diminished the sexual experience.

While some men expressed interest in using female condoms with their partner in the future, others preferred them over male condoms:

When I started to attend these sessions I never thought I’ll use a female condom in my life but now me and my partner we are now enjoying female condom more than male condom.

(David, age 37)

Positive associations with female condoms included efficacy of protection and that the female condom was sexually pleasurable. Interestingly, even when men preferred the female condom, the decision to use them was often guided by partner response to the product. For instance, if a woman found female condoms uncomfortable or painful, the couple would not continue to use them.

Male involvement during pregnancy and PMTCT

Women

Women discussed their feelings regarding male involvement during pregnancy and the PMTCT process. During role-plays regarding partner failure to attend appointments, women responded with a range of emotions, such as ‘angry’, ‘hurt’ and ‘disappointed.’ One woman role-played her husband’s reaction to her invitation to attend an antenatal appointment:

Why do you want me to come with you? I am busy and don’t have time, anyway a clinic is for women not men.

(Karen, age 33)

Women often perceived men as apprehensive and uninterested in attending clinic appointments. Although some men might accompany their partner to an appointment, they usually wait in the clinic area instead of entering the consulting room with their partner. Alternately, women indicated the group intervention had a positive impact on partner involvement, including increasing the number of times they accompanied them to the clinic and on the quality of their communication (i.e., increasing effective communication).

Men

In contrast to the comments made by women, men suggested they would feel ‘sad’ and ‘hurt’ if their partner neglected to invite them to accompany them to an antenatal clinic visit. Some men expressed concerns of infidelity if their partner did not ask them to attend clinic. Other men did not feel comfortable asking if they could attend clinic appointments for fear of coming across as being ‘controlling’.

A few men (n = 5) indicated it was not their responsibility to care for their partner during pregnancy. One man stated:

I had this mind to take my partner home to live with my parents to avoid all the things you talking about.

(Frank, age 24)

The other men in his group reacted strongly to his comment. One man said:

When she is away she will be by herself and you would be on your own. Now she would have every right to think that you may be cheating on her. Remember that we have been discussing the negative thoughts issue. What you thinking of doing or are doing will cause unnecessary conflict between you and your partner.

(Christopher, age 44)

Another participant followed with:

I never thought I should be there for the whole pregnancy process. But in all truth they really do need us to be there for them because they even think that we do not think they are still beautiful as they were before they fell pregnant and that is where you get things like them having to be insecure.

(Phineas, age 39)

Although some men did express apathy toward their partner during pregnancy, generally they expressed concern and a sense of duty to care for them.

Male-specific core themes

HIV-related knowledge

By the time of the final session, men were demonstrating increased awareness and knowledge of sexually transmitted infections (STIs)/HIV and adherence to medication and treatment. They attributed this increased knowledge to the instruction they received during the previous sessions. For instance, they learned that taking their HIV medication as prescribed could contribute to living longer and that receiving treatment for an infection was necessary:

I once had [thrush] on my private parts and my partner had it too but we did get treatment and now we both know if any of us finds something that is not normal on them we have to go the nearest clinic.

(Samuel, age 26)

Men discussed treatment options, such as attending a medical clinic or visiting a traditional healer. For some, it was customary to receive medical treatment from a traditional healer instead of a medical doctor. However, men stated that often the treatment provided by the traditional healer was not sufficient and they had to seek medical advice:

Last year I had unprotected sex so I got infected with Gonorrhoea. I went to an inyanga [traditional healer] and he gave me muti [water mixed with traditional herbs] and I continue to drink that for three days but nothing changed so I decided to tell my friend about this and he advised me to go to the clinic…nurses told to fetch the girl that infected me, so that she can be treated too and I did so.

(Tobias, age 31)

Male circumcision

Men were knowledgeable about male circumcision, both about traditional practices and the more modern medical circumcision. Contrary to expectations, men were open to discussing medical circumcision and offered valuable insights. Most men understood the health-related benefits associated with male circumcision, such as reducing STI-risk, although they expressed erroneous beliefs regarding the practice itself.

Some beliefs were particularly alarming. Specifically, if circumcised, a man could ‘never’ become infected with HIV. Another belief was that if a man was not circumcised, he was certainly going to become infected with HIV regardless of any precautions he could take. The lay counsellors corrected these erroneous beliefs, as well as other concerns that were discussed (e.g., pain associated with the procedure and recovery, and sexual function post-circumcision).

A major concern for men, and source of significant stress, was stigma. They feared how they would be perceived by their peers and society if they were to be medically circumcised instead of the traditional method. For many, it was customary to become circumcised by traditional methods through an initiation school:

I want to be circumcised at the clinic. The problem is that in our culture in order to be a man you must go to initiation school.

(Elias, age 26)

When asked what would happen if he were to go to have the modern medical circumcision procedure, he replied:

My friends will call me names and that I’m not a real man.

Although culturally embedded practices, such as traditional circumcision, clash with more modern medical practices, some men expressed interest in medical circumcision. For instance, one man related a personal tragedy that ultimately impacted his perception of circumcision practices:

Going to initiation school for circumcision is so old fashioned. Just go to hospital as I did after they give you strongest pain killers you won’t even feel a pain. My brother died while at initiation school so I decided not to go there. Even my children won’t go there.

(Baruti, age 23)

Discussion

This study sought to elicit the thoughts and perceptions of pregnant South African couples participating in gender-concordant group intervention sessions on sexual communication and PMTCT process. Women and their partners were particularly open about their own HIV-serostatus and their experiences with disclosure, sexual barriers and male participation in antenatal care. Both discussed similar key issues, although, men also focused on STI/HIV-related knowledge and male circumcision.

Women and men were particularly engaged in discussions surrounding sexual negotiation and HIV disclosure and the relationship between disclosure and trust (Peltzer and Mlambo 2010). Women, who perceived their relationship as supportive, loving and trusting would disclose without fear of rejection or abandonment. Some women noted they would provide their partner with support should they test positive for HIV, while others asserted they would abandon their partner. Women were able to make positive associations between the reciprocity of disclosing to their partner and receiving encouragement and support. As Peltzer and colleagues (2010) found, disclosure could be a springboard to the adoption of preventive behaviours by the partner, whereby disclosure by the positive partner encouraged the other partner to seek HIV testing. Improving trust may be a significant component of intervention programs aimed at facilitating disclosure among South African couples.

Interestingly, nuances of non-verbal behaviours were interpreted by partners as a confirmation of HIV-serostatus. For example, if a male partner was tested for HIV and did not share his result, his non-disclosure was viewed as confirmation of his HIV-seropositive status. Women expressed concern and fear of being tricked by their non-disclosing partners into continued unprotected sex and of being infected purposefully. Exploring the perceived meaning of disclosure silence (i.e., not disclosing HIV-serostatus to a partner) should be addressed with couples in an effort to improve awareness of its detrimental impact on the relationship.

Men also expressed concern with sexual negotiation and HIV disclosure. As found in previous studies (Peltzer et al. 2010), some believed it was necessary to disclose, regardless of the risks involved (e.g., rejection). HIV disclosure was perceived as emotionally cleansing, healing and to a degree cathartic. As would be expected, men were apprehensive to disclose for fear of how their partner might react. For many, the concern was that women would react hurtfully, emotionally, hold a grudge, and confide in other women.

Men were agreeable to making positive changes to improve their communication skills with their partners. Although seen as a difficult and arduous process, men repeatedly noted how the communication skills taught in the sessions had improved the way they conversed and the tenor of disagreements with their partners. For example, in addition to increasing communication and stimulating discussions not otherwise common, men reported improved listening skills and more ease in expressing their thoughts and feelings. As found in other sub-Saharan African studies, increased HIV disclosure among men and women is possible following an intervention targeting sexual communication.

Likely due to the nature of the intervention, both gender groups focused on the efficacy of condoms and product preference. The majority of women described their negative reactions and experiences with male condoms, although these reactions were overshadowed by enthusiasm for the female condom. Overall, women perceived the female condom to be more convenient and empowering to use, despite concerns related to proper insertion and hindering spontaneous sex. Women described their partners’ reactions to the male and female condoms as mixed. Sexual risk behaviour interventions should explore ways to educate proper female condom use, which may aide in overall increased use of sexual protection.

Unlike women, the men’s stated experiences with both condom types were negative and centred on fidelity. Some complained about condom noise during sex and the time taken for insertion, but most contended they would be willing to try the female condom again. For men, deciding to use condoms was often guided by their partner’s reaction, indicating that female partners may have more power in the sexual negotiation of condom use than believed. This is similar to results found by Jones and colleagues (2009) among couples in Zambia. Self reported increased sexual barrier use and negotiation among participating couples highlights the potential for the intervention to increase protection.

Both women’s and men’s groups discussed male involvement during the PMTCT process, and overall, women viewed their partners as uninvolved and uninterested in becoming engaged in the process. This is consistent with the literature (Auvinen, Suominen and Valimaki 2010); however, in this study the majority of women wanted increased male involvement, and indicated that this would be a testament of their partners’ dedication and love. In contrast, men shared feelings of sadness and neglect at not being asked by their partners to be involved in their antenatal care. This mutual misperception underscores the importance of increasing communication about shared engagement in antenatal care.

The men who were not interested in becoming involved during pregnancy, were strongly criticised by the other group members. The majority expressed concern and a strong desire to care for their pregnant partners. Since a pregnant woman is not only caring for herself, but also for her unborn child, pregnancy provides a critical window of opportunity to educate and improve healthy behaviours. A man’s desire to care for his pregnant partner could also serve as a teaching moment for men to receive HIV prevention education. For instance, medical clinics should approach men in the waiting area and use this time to engage them by providing educational information on ante- and post-natal care. A man’s desire to be involved in the antenatal care process is often overlooked. Behavioural interventions should explore the level of male involvement that would be adequate for both partners and that would provide the couple with a sense of fulfilment without feeling dominated or ostracised.

Male participants shared their own experiences with STIs and treatment, and many expressed interest in medical circumcision. Though most were knowledgeable about the practice of traditional male circumcision and the benefits of medical male circumcision, non-circumcised men were concerned as to how they would be perceived by their peers and society if they were to be medically circumcised. Stigma associated with non-traditional medical circumcision appeared to influence men’s consideration of undergoing surgery. Medical providers and behavioural interventions should address perceived stigma and common misconceptions surrounding traditional and modern medical circumcision, providing the patient with enough information so that he could make an informed decision on which procedure to choose.

Also influenced by social perception, women expressed apprehension regarding sexual negotiation, fearing rejection or embarrassment. For some, the fear was so intense that they refused to discuss it with their partner. The effects of domestic violence on sexual discussions and HIV disclosure in antenatal women have been described in the literature (Medley et al. 2004). Yet, discussions of IPV among both women and men were not sufficient for it to become a core theme. Regardless, it does not minimise violence among this sample. Even though women and men felt at ease discussing other sensitive issues, the perceived stigma and shame associated with IPV may have led to couples being more guarded in this respect. Also, disclosure of IPV may have been especially difficult in a group setting. Intervening with couples at an individual level may be more effective. A group setting may not provide an environment that is safe for women or men to disclose violence. Gender-based violence has been consistently reported as a key factor in a woman’s risk of HIV infection. Therefore, future studies should explore IPV among couples and develop culturally-sensitive role-plays to address this issue in gender-concordant group settings or at the individual level.

Limitations of this study include structural and environmental problems. At times, gender-concordant groups were held in adjacent rooms due to limited space allocation, which may have increased inhibitions and stifled openness because of fear of being overheard by the partner, patients or staff. Although numerous themes the researchers felt were essential to the study’s aims were discussed, some did not reach saturation, and therefore, were not designated as core themes. Such themes included IPV, breastfeeding and traditional healing. These themes may be an important component of the PMTCT process and may warrant further exploration.

Conclusion

Although PMTCT programmes have significantly reduced HIV/AIDS-related child mortality around the world (Joseph 2004; Theuring et al. 2009), mother-to-child transmission rates of HIV remain high in South Africa. Women who are not receiving adequate antenatal care place themselves, their child, and partner at risk. Many women do not complete or engage in post-natal or primary infant care, which becomes a missed opportunity for the newborn to receive dual therapy. In addition, women who are provided with medication for themselves or their children do not follow through with the treatment regimen (Peltzer, Mlambo, and Phaweni 2010). Factors such as unwillingness to disclose to partner/family and stigma (Ujiji et al. 2011), may affect a woman’s decision to take medication or provide it to the newborn.

These personal and candid discussions indicate a continued need to break down barriers that prevent effective communication between couples. Openness among women and men, willingness to share HIV diagnosis among partners and the comfort experienced by men in sharing their feelings and experiences with other men may signal the beginning of positive change. Improving communication between the couple, increasing male involvement in the PMTCT process, and demystifying HIV may bring us closer to bridging the gap between knowledge about prevention and sexual-behaviour change.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by NIH, NIAID, PEPFAR and OAR, under grant number P30A1073961-S. The authors thank the field staff and participants, without whom this study could not have been done.

References

- Agu VU. Comprehensive report: The development of harmonized minimum standards for guidance on HIV testing and counselling and PMTCT of HIV in the SADC region: PMTCT country report. Lesotho: African Development Bank; 2009. [accessed August 23, 2012]. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/Research_Publication-21632.phtml. [Google Scholar]

- Aluisio A, Richardson BA, Bosire R, John-Steward G, Mbori-Ngacha D, Farquhar C. Male antenatal attendance and HIV testing are associated with decreased infant HIV-infection and increased HIV-free survival. Journal of Acquired Immunological Defence Syndrome. 2011;56(1):76–82. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fdb4c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auvinen J, Suominen T, Valimaki M. Male participation and prevention of HIV mother-to-child-transmission in Africa. Psychology, Health and Medicine. 2010;15(3):288–313. doi: 10.1080/13548501003615290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Mlay R, Schwandt HM, Lyamuya E. Comparing couples’ and individual voluntary counselling and testing for HIV at antenatal clinics in Tanzania. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(3):558–66. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9607-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. 2008 National antenatal sentinel HIV and syphilis prevalence survey, South Africa. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Chitalu N, Ndubani P, Mumbi M, Weiss SM, Villar-Loubet O, Vamos S, Waldrop-Valverde D. Sexual-risk reduction among Zambian couples. Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance. 2009;6(2):69–75. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2009.9724932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Bhat G, Weiss SM, Feldman DA, Bwalya V. Influencing sexual practices among HIV-positive Zambian women. AIDS Care. 2006;18:629–35. doi: 10.1080/09540120500415371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Ross D, Weiss SM, Bhat G, Chitalu N. Influence of partner participation on sexual risk behaviour reduction among HIV-positive Zambian women. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:92–100. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph D. Improving on a successful model for promoting couples’ VCT in two African capitals. Presentation at the XV International AIDS Conference; July 13; Bangkok, Thailand. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kinuthia J, Kiarie JN, Farquhar C, Richardson B, Nduati R, Mbori-Ngacha D, John-Stewart G. Co-factors for HIV incidence during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Poster presentation at the 17th Annual Conference for Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 19; San Francisco, CA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Moodley D, Groves AK. Defining male support during and after pregnancy from the perspective of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in Durban, South Africa. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2011;56:325–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbonye AK, Hansen KS, Wamono F, Magnussen P. Barriers to prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services in Uganda. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2009;9:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S002193200999040X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV-serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries. WHO Bulletin. 2004;82:299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindry D, Maman S, Chirowodza A, Muravha T, van Rooyen H, Coates T. Looking to the future: South African men and women negotiating HIV risk and relationship intimacy. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(5):589–602. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.560965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugo NR, Heffron R, Donnell D, Wald A, Were EO, Rees H, Celum C, et al. Increased risk of HIV-1 transmission in pregnancy: A prospective study among African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. AIDS. 2011;25(15):1887–95. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health. National antenatal sentinel HIV and syphilis prevalence survey in South Africa, 2010. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Jones DL, Weiss SM, Shikwane E. Promoting male involvement to improve PMTCT uptake and reduce antenatal HIV-infection. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(778):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Mlambo G. Factors determining HIV viral testing of infants in the context of mother-to-child-transmission. Acta Paediatrica. 2010;99(4):590–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Mlambo G, Phaweni K. Factors determining prenatal HIV testing for PMTCT of HIV in Mpumalanga, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(5):1115–23. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Mlambo M, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Ladzani R. Determinants of adherence to a single-dose nevirapine regimen for the PMTCT in Gert Sibande district in South Africa. Acta Paediatrica. 2010;99(5):699–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rispel LC, Cloete A, Metcalf CA, Moody K, Caswell G. ‘It [HIV] is part of the relationship’: Exploring communication among HIV-serodiscordant couples in South Africa and Tanzania. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2012;14(3):257–68. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.621448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O. South African national HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, behaviour and communication survey, 2008: The health of our children. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Theuring S, Mbezi P, Luvanda H, Jordan-Harder B, Kunz A, Harms G. Male involvement in PMTCT services in Mbeya Region, Tanzania. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:92–102. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser MJ, Neufeld S, de Villiers A, Makin JD, Forsyth BW. To tell or not to tell: South African women’s disclosure of HIV status during pregnancy. AIDS Care. 2008;20(9):1138–45. doi: 10.1080/09540120701842779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujiji OA, Ekstrom AM, Ilako F, Indalo D, Wamalwa D, Rubenson B. Reasoning and deciding PMTCT-adherence during pregnancy among women living with HIV in Kenya. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(7):829–40. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.583682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand H, Ramjee G. Combined impact of sexual-risk behaviors for HIV-seroconversion among women in Durban, South Africa: Implications for prevention policy and planning. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(2):479–86. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9845-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrod R. Masculinity and the persistence of AIDS stigma. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(4):443–56. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.542565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]