Summary

The existence of extracellular phosphoproteins has been acknowledged for over a century. However, research in this area has been undeveloped largely because the kinases that phosphorylate secreted proteins have escaped identification. Fam20C is a kinase that phosphorylates S-x-E/pS motifs on proteins in milk and in the extracellular matrix of bones and teeth. Here, we show that Fam20C generates the majority of the extracellular phosphoproteome. Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, mass spectrometry, and biochemistry, we identify more than 100 secreted phosphoproteins as genuine Fam20C substrates. Further, we show that Fam20C exhibits broader substrate specificity than previously appreciated. Functional annotations of Fam20C substrates suggest roles for the kinase beyond biomineralization, including lipid homeostasis, wound healing, and cell migration and adhesion. Our results establish Fam20C as the major secretory pathway protein kinase and serve as a foundation for new areas of investigation into the role of secreted protein phosphorylation in human biology and disease.

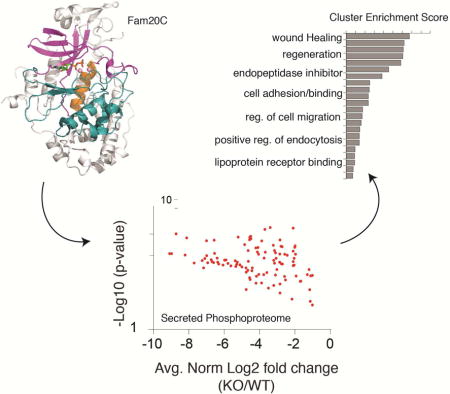

TOC image

The kinases that catalyze the phosphorylation of secreted proteins have only recently been identified, with Fam20C being identified as the kinase responsible for generating the vast majority of the secreted phosphoproteome, including substrates thought to drive tumor cell migration.

Introduction

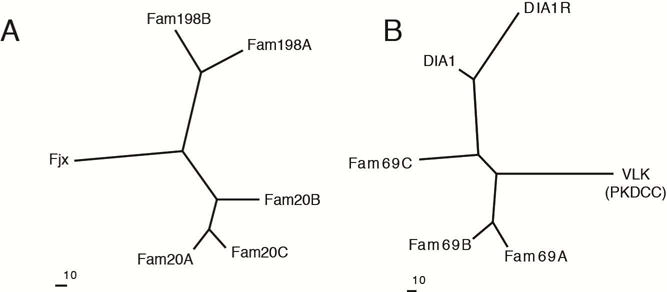

Extracellular protein phosphorylation dates back to 1883, when the secreted protein casein was shown to contain phosphate (Hammarsten, 1883). More than a century later, Manning and colleagues assembled an evolutionary tree depicting over 500 human protein kinases that phosphorylate a diverse array of substrates (Manning et al., 2002). However, evidence is lacking that any of these kinases localize within the secretory pathway where they could encounter proteins destined for secretion. We recently identified a small family of kinases that phosphorylate secreted proteins and proteoglycans (Figure 1A) (Tagliabracci et al., 2012). These enzymes bear little sequence similarity to canonical protein kinases; nevertheless, some of them are endowed with protein and sugar kinase activities. (Ishikawa et al., 2008; Koike et al., 2009; Tagliabracci et al., 2012; Tagliabracci et al., 2013a). We demonstrated that one of these kinases, Fam20C, is the bona fide “Golgi casein kinase”, an enzyme that escaped identification for many years (Tagliabracci et al., 2012). Fam20C phosphorylates secreted proteins within S-x-E/pS motifs, including casein, fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) and members of the small integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoprotein (SIBLING) family (Ishikawa et al., 2012; Lindberg et al., 2014; Tagliabracci et al., 2012; Tagliabracci et al., 2014). The crystal structure of the Fam20C orthologue from Caenorhabditis elegans displayed an atypical kinase-like fold and revealed several unique features, such as disulfide bridges, N-linked glycosylations and a novel insertion domain that is conserved in all Fam20 family members (Xiao et al., 2013).

Figure 1. The Fam20C- and VLK-related secretory pathway kinases.

(A, B) Phylogenetic trees built with MOLPHY using distances (-J option) calculated from an alignment of representative human proteins depicting (A) the Fam20C-related kinases and (B) the VLK-related kinases (Fjx1, Four-jointed box 1, DIA1; Deleted in Autism 1, DIA1R; DIA1-Related). See also Figure S1.

The members of this family of secretory pathway kinases can phosphorylate both proteins and carbohydrates. In Drosophila, four-jointed regulates planar cell polarity by phosphorylating cadherin domains of Fat and Dachsous (Ishikawa et al., 2008). Although the substrates for Fam20A, Fam198A and Fam198B are unknown, Fam20B phosphorylates a xylose residue within the tetrasaccharide linkage region of proteoglycans (Koike et al., 2009). This phosphorylation markedly stimulates the activity of galactosyltransferase II to promote proteoglycan biosynthesis (Wen et al., 2014).

Moreover, a distantly related protein, Sgk196, originally annotated as a pseudokinase, was recently shown to localize in the ER/Golgi lumen and phosphorylate a mannose residue on α-dystroglycan (Yoshida-Moriguchi et al., 2013). The inability to carry out this phosphorylation due to loss-of-function mutations in the human SGK196 gene results in a congenital form of muscular dystrophy (Jae et al., 2013; von Renesse et al., 2014).

In addition to the aforementioned kinases, the vertebrate lonesome kinase (VLK) is a secreted kinase that phosphorylates extracellular proteins on tyrosine residues (Bordoli et al., 2014). Interestingly, several proteins related to VLK also localize in the secretory pathway and are predicted to have a kinase-like fold (Figure 1B and Figure S1) (Dudkiewicz et al., 2013). These proteins are poorly characterized molecularly; however, several of them have been genetically linked to neurological disorders, including Deleted in Autism-1 (DIA1) and DIA1-Related (DIA1R) (Aziz et al., 2011a, b; Morrow et al., 2008; Tennant-Eyles et al., 2011).

Phosphoproteomic studies have revealed that more than two-thirds of human serum (Zhou et al., 2009), plasma (Carrascal et al., 2010) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Bahl et al., 2008) phosphoproteins contain phosphate within a S-x-E/pS motif (Table S1). These observations suggest that kinases in the secretory pathway may have overlapping substrate specificity. Here, we provide evidence that Fam20C is responsible for phosphorylating the vast majority of secreted phosphoproteins. We identify more than 100 secreted phosphoproteins as genuine Fam20C substrates and uncover Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation sites within or surrounding residues that are mutated in human diseases (i.e. PCSK9, BMP4). Functional annotations of Fam20C substrates suggest roles for the kinase in a broad range of biological processes, including lipid homeostasis, endopeptidase inhibitor activity, wound healing and cell adhesion and migration. Furthermore, we demonstrate that depletion of Fam20C in breast cancer cells has a dramatic affect on cell adhesion, migration and invasion. We anticipate that this work will open new areas of research on extracellular protein phosphorylation in human biology and disease.

Results

Fam20C is unique amongst all known secretory pathway kinases

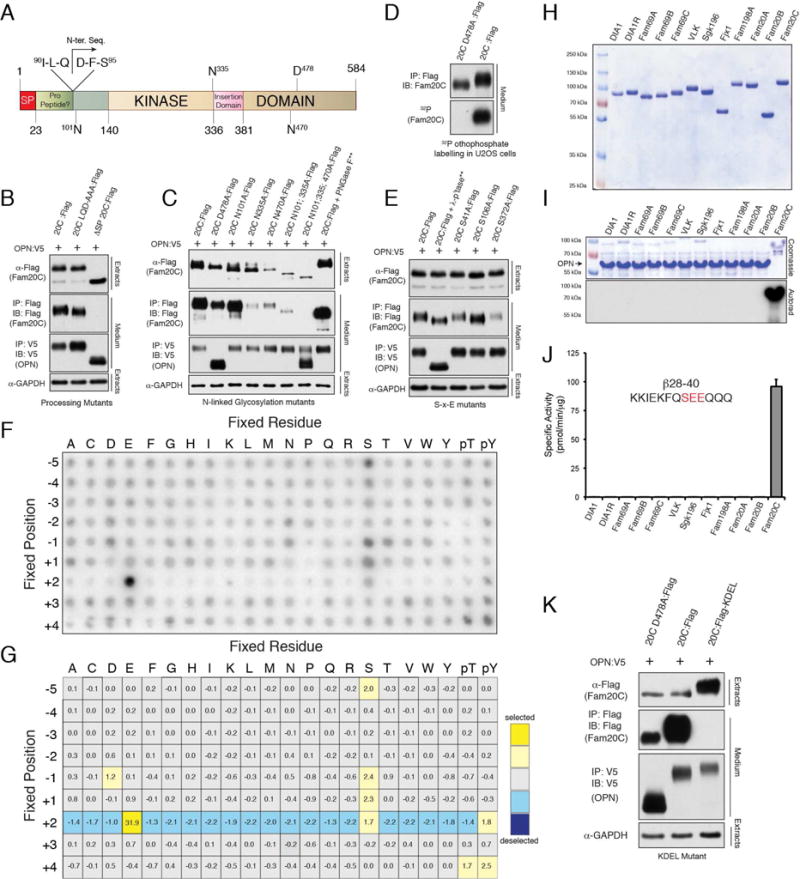

Many secretory pathway proteins undergo posttranslational modifications within the lumen of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus. N-terminal sequencing analysis of Fam20C purified from the conditioned medium of HEK293T cells revealed the mature protein to be truncated by 92 residues (Figure 2A). Mutation of a 3 amino acid stretch that spans this region (91LQD93 to 91AAA93) did not affect Fam20C secretion or activity as judged by its ability to induce a mobility change in the Fam20C substrate osteopontin (OPN) (Figure 2B). Human Fam20C is N-linked glycosylated on three Asn residues (N101, N335 and N470), and glycosylation appears to be important for proper folding of the enzyme because mutating these residues to Ala had a dramatic effect on Fam20C secretion (Figure 2C). Moreover, mutation of all three sites had a profound effect on Fam20C activity.

Figure 2. Fam20C activity is unique amongst the known secretory pathway kinases.

(A) Schematic representation of human Fam20C depicting the signal peptide (SP; red), the putative pro-region (green), the kinase domain (tan) and the insertion domain (pink). The mature, C-terminally tagged Fam20C purified from conditioned medium of HEK293T cells is truncated by 92 amino acids as determined by Edman degradation. The amino acid sequence surrounding this region is shown. The N-linked glycosylation sites and the “DFG” metal binding residue, D478, are also depicted.

(B) Protein immunoblotting of V5 and Flag immunoprecipitates from conditioned medium (CM) of U2OS cells co-expressing V5-tagged OPN (OPN:V5) with either WT Fam20C (20C:Flag), 91LQD93-91AAA93 Fam20C (20CLQD-AAA:Flag) or Fam20C lacking the signal peptide (ΔSP20C:Flag). Extracts were analyzed for Flag-Fam20C (or mutants) and GAPDH.

(C) Protein immunoblotting of V5 and Flag immunoprecipitates from CM of U2OS cells co-expressing V5-tagged OPN (OPN:V5) with either WT Fam20C (20C:Flag), catalytically inactive D478A (20CD478A:Flag), or various N-linked glycosylation mutants. Extracts were analyzed for Flag-Fam20C (or mutants) and GAPDH. ** Denotes that 20C:Flag immunoprecipitates were treated with PNGase-F.

(D) Protein immunoblotting and autoradiography of Flag-immunoprecipitates from CM of 32P-orthophosphate labeled U2OS cells expressing WT Fam20C (20C:Flag) or catalytically inactive D478A (20C D478A:Flag).

(E) Protein immunoblotting of V5 and Flag immunoprecipitates from CM of U2OS cells co-expressing V5-tagged OPN (OPN:V5) with either WT Fam20C (20C:Flag) or potential S-x-E phosphosite Flag-tagged mutants (S41A, S106A and S372A). Extracts were analyzed for Flag-Fam20C (or mutants) and GAPDH. ** Denotes that 20C:Flag and OPN:V5 immunoprecipitates were treated with λ-phosphatase (λ-p’tase).

(F) Characterization of a consensus Fam20C phosphorylation motif by phosphorylation of a positional scanning peptide library. The phosphorimage depicts incorporation of 32P into a mixture of biotinylated peptides bound to a streptavidin-coated membrane. The positions are numbered relative to the central phospho-acceptors.

(G) Position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) resulting from quantification of the in vitro phosphorylation of the positional scanning peptide library by Fam20C.

(H) SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining of MBP-tagged members of the Fam20C- and VLK -related kinases, and Sgk196, expressed and purified from CM of insect cells. (The tags for Fjx1 and Fam20B were cleaved with TEV).

(I) The Fam20C- and VLK -related kinases, and Sgk196 were incubated with OPN in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

(J) The Fam20C- and VLK -related kinases and Sgk196 were incubated with β28–40 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Incorporated radioactivity was quantified by scintillation counting.

Note: Fam198B was not included in these reactions because we could not produce the protein in mammalian or insect cells despite several attempts. However, when Flag-tagged Fam198B was coexpressed with V5-tagged Fetuin A (FetA) in mammalian cells metabolically labeled with 32P-orthophosphate, we did not observe 32P incorporation into V5-immunoprecipitates (not shown). FetA is an S-x-E containing phosphoprotein that is a Fam20C substrate (See Figure 4A and D). We therefore conclude that Fam20C activity is unique amongst the known secretory pathway kinases.

(K) Protein immunoblotting of V5 and Flag immunoprecipitates from CM of U2OS cells co-expressing V5-tagged OPN (OPN:V5) with either WT (20C:Flag), catalytically inactive D478A (20C D478A:Flag), or Fam20CKDEL (20C:Flag-KDEL). Extracts were analyzed for Flag-Fam20C (or mutants) and GAPDH. See also Figure S2.

To determine if Fam20C is itself a phosphoprotein, we expressed Flag-tagged Fam20C in 32P orthophosphate labeled U2OS cells. Examination of Flag-immunoprecipitates from conditioned medium revealed that WT Fam20C, but not the catalytically inactive D478A mutant, incorporated 32P (Figure 2D). These results suggest that Fam20C undergoes autophosphorylation. There are 3 Fam20C consensus S-x-E motifs within the kinase; however, individual mutation of each Ser to Ala did not affect Fam20C activity and had modest effects on Fam20C secretion (Figure 2E).

Studies using peptide substrates derived from known secreted phosphoproteins have suggested that Fam20C phosphorylates Ser residues within a S-x-E/pS motif (Ishikawa et al., 2012; Lasa-Benito et al., 1996; Meggio et al., 1989; Tagliabracci et al., 2012). To determine Fam20C specificity in an unbiased manner, we screened an arrayed combinatorial peptide library consisting of 198 biotinylated substrates (Hutti et al., 2004). Fam20C strongly selected Glu at the +2 position, but displayed only minor selectivity at other positions (Figure 2F and G). This extraordinarily specific pattern of selectivity at the +2 position is unique among all kinases previously profiled (Mok et al., 2010).

To test whether other secretory kinases could phosphorylate S-x-E/pS motifs, we expressed and purified each of the Fam20C- and VLK-related proteins, as well as Sgk196, fused to maltose binding protein (MBP) using an insect cell expression system (Figure 2H). We then performed in vitro kinase assays with recombinant OPN, and a synthetic peptide representing an S-x-E phosphorylation site in bovine β-casein (β28–40) as substrates (Figure 2I and J). Fam20C displayed a robust ability to phosphorylate OPN and β28–40, whereas the other secretory pathway kinases did not, even though several of these proteins were active enzymes based on their ability to autophosphorylate. We conclude that Fam20C specificity is unique amongst the known secretory pathway kinases.

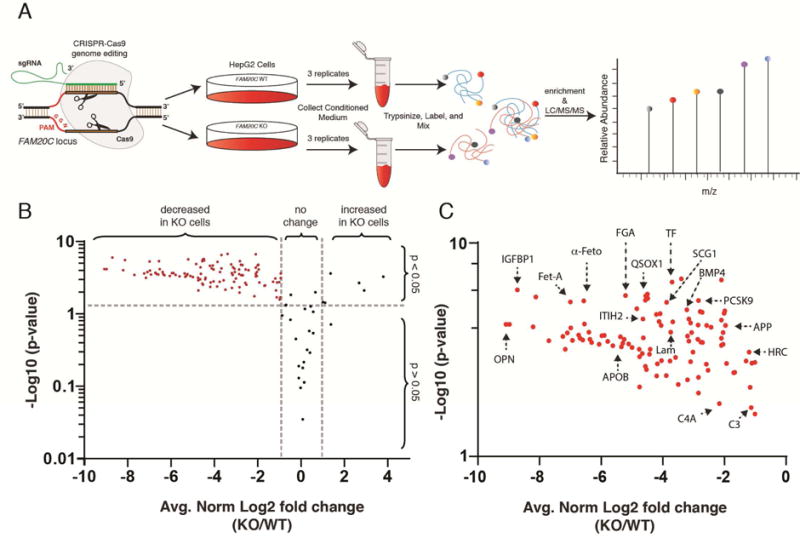

Fam20C generates the majority of secreted phosphoproteome

We engineered a C-terminal KDEL sequence on Fam20C to prevent secretion of the kinase. When expressed in U2OS cells, Fam20C containing a C-terminal KDEL sequence was not secreted, yet could still phosphorylate secreted OPN (Figure 2K and S2). Thus, it appears that phosphorylation of Fam20C substrates takes place in the lumen of the secretory pathway in cells where both the kinase and substrate are produced. These results also suggest that ATP is transported into the lumen of the secretory pathway; however the mechanism by which this occurs in unknown. Because many serum and plasma phosphoproteins are synthesized and secreted from hepatocytes, we performed subcellular fractionation experiments on rat liver and detected endogenous Fam20C in the lumen of highly enriched Golgi fractions (Figure S3A and B). Therefore, we utilized the liver cell line HepG2 as a model system to ascertain the relative contribution of Fam20C kinase activity to the secreted phosphoproteome. We generated Fam20C knockout (KO) HepG2 cells by means of CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing (Figure S3C–E) (Cong et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013). Using these cells, we performed a quantitative analysis of the Fam20C-dependent secreted phosphoproteome (Figure 3A). We collected serum-free conditioned medium from WT and Fam20C KO cells, trypsinized the proteins, and labeled them with isobaric tags (6-plex TMT). After combining the samples, phosphopeptides were enriched, fractionated and analyzed by LC-MS/MS (Figure S4 and Excel file S1). We restricted our analyses to phosphoproteins that are secreted via the conventional secretory pathway (i.e. signal peptide or luminal/extracellular domain of transmembrane proteins) and identified approximately 150 phosphopeptides representing more than 50 distinct phosphoproteins (Figure 3B, C and Table 1). Remarkably, Fam20C KO cells displayed a > 2-fold reduction in approximately 90% of the significantly quantified phosphopeptides (See Supplemental Text). These results demonstrate that the majority of HepG2 secreted phosphoproteins are Fam20C substrates. Importantly, several HepG2 secreted phosphoproteins have been identified in human serum (Zhou et al., 2009) and plasma (Carrascal et al., 2010) phosphoproteomes (Tables 1 and S1).

Figure 3. Fam20C generates the majority of the HepG2 extracellular phosphoproteome.

(A) Schematic representation of the workflow used in these studies.

(B) Volcano plot depicting the log2 of fold phosphorylation change (normalized to protein abundance) versus -log10(p-value) for phosphosites on secretory pathway proteins. The phosphopeptides marked in red displayed a statistically significant decrease in Fam20C KO HepG2 cells (log2 fold change ≤ −1; −log10(p-value) ≥ 1.3).

(C) Zoomed in view of the volcano plot in (B) highlighting the phosphopeptides that significantly decreased in Fam20C KO cells. OPN; osteopontin, IGFBP1; insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1, FETUA; fetuin A, α-Feto; α-fetoprotein, ITIH2; Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2, APOB; apolipoprotein B, FGA; fibrinogen gamma chain, QSOX1; quiescin Q6 sulfhydryl oxidase-1, Lam; laminin, SCG1; secretogranin-1, TF; transferrin, APOL1; apolipoprotein L1, BMP4; bone morphogenic protein-4, PCSK9; Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type-9, APP; Aβ precursor protein, HRC; histidine rich calcium binding protein, C3; complement component C3, C4A; complement component. See also Figure S3.

Table 1.

Fam20C-dependent phosphosites in secretory pathway proteins from HepG2 cells. Phosphoserines within a Fam20C consensus motif (pS-x-E/pS) are indicated by a lower case “s”. Non pS-x-E/pS sites are indicated by a capital letter (S, T or Y). The asterisk (*) indicates if the protein was confirmed to be a Fam20C substrate in either cell-based or in vitro kinase assays. See also Figure S4 and Excel file S1.

| Function | Protein Name (Gene Symbol) | Phosphosites |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid binding & homeostasis | Apolipoprotein A2 (APOA2) * | s54, s68 |

| Apolipoprotein B (APOB) | s4048 | |

| Apolipoprotein E (APOE) * | s147 | |

| Apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) * | s327, s330, s352, s355 | |

| Apolipoprotein A-V (APOA5) | T55 | |

| Proprotein convertase subtilisin type 9 (PCSK9) * | s47, s688 | |

| BPI fold-containing family B member 2 (BPIFB2) | T52, s60 | |

| IGFBPs | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 (IGFBP1) * | s45, S156, T157, Y158, T193, s194, S199, s242 |

| Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP3) | s148 | |

| Neuropeptides | Secretogranin 1 (CHBG) * | s130, s225, s367, s377, S380, Y401 |

| Cystatin Family | Cystatin-C (CST3) * | s43 |

| Kininogen-1 (KNG1) | s332 | |

| Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein (P02765) (AHSG) | S135, s138, s328, s330 | |

| Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein (C9JV77) (AHSG) * | s139, T320, S326, s331 | |

| Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) * | S111, S115, s117, s344, s444, S445 | |

| Protease Inhibitors & metallo-proteases | Alpha-1-anti-trypsin (SERPINA1) | S38 |

| Protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor (SERPINA10) | s56 | |

| Antithrombin III (SERPINC1) | T63, S68 | |

| Heparin cofactor 2 (SERPIND1) | S37 | |

| Glypican 3 (GPC3) | S352 | |

| Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor H2 (ITIH2) | s60, s466, s886 | |

| Disintegrin and metalloprotease domain-containing protein 10 (ADAM10) | T719 | |

| Calcium Binding and homeostasis | Osteopontin (Isoform C) (SPP1) * | T163, S164, s168, S188, S192, s197, Y198, S201, s207, T210, S212, S216, s227, S231, s236, S240, s243, s248, s253, s264, s276, s281, s283, S284 |

| Osteopontin (Isoform A) (SPP1) | s63, T190, S191, s195, s224, s234, s228, s254, S258, s263, s270, s275, s280, s291 | |

| Osteopontin (Isoform 5) (SPP1) | s26, s27 | |

| Highly similar to osteopontin (B7Z351) (SPP1) | s75, s76 | |

| Reticulocalbin-1 (RCN1) | s80 | |

| Histidine rich calcium binding protein (HRC) * | T76, s119, s145, s358, s409, s431, s494, s567 | |

| Nucleobindin-1 (NUCB1) * | s86, s369, T148 | |

| Stanniocalcin (STC2) * | S250, s251, T254 | |

| Calumenin, Isoform 4 (CALU) | s77 | |

| Glucosidase 2 subunit beta (PRKCSH) | S24, s168 | |

| Serum albumin (ALB) | S29, s82, s91, T109 | |

| Adhesion | Cadherin-2 (CDH2) | s96 |

| Amyloid beta A4 protein (APP) | s385, s441 | |

| Extracellular Matrix | Fibronectin, isoform 1 (FN1) * | s2384 |

| Fibronectin, isoform 15 (FN1) | s2475 | |

| Laminin subunit beta-1 (LAMB1) | s1502, s1520, s1690, s1706 | |

| Laminin subunit beta-2 (LAMB2) | s1532 | |

| Laminin subunit gamma-1 (LAMC1) | s1149 | |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 (QSOX1) * | s426 | |

| Bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4) | s91 | |

| Testican (SPOK2) | s72 | |

| Versican core protein (VCAN) | s2116 | |

| Matrillin-3 (MATN3) | s441, T442 | |

| Complement System | Complement C3 (C3) | s38, s70, s297, S303, S672, S968, s1321, s1573 |

| Isoform 2 of Complement C4-A (C4A) | s918 | |

| Blood Clotting | Coagulation factor V (F5) | s859 |

| Fibrinogen alpha chain (FGA) | s45, s56, s364, S524, S560, S609 | |

| Fibrinogen gamma chain (FGG) | s68 | |

| Vitamin K-dependent protein C (PROC) | s347 | |

| Von Willebrand factor A domain-containing protein 1 (VWA1) | S74, S80, Y83, s93 | |

| Signaling & protein transport | Trans-Golgi network integral membrane protein 2 (TGOLN2) * | s71, S221, s298, T302, s351 |

| Neurosecretory protein VGF (VGF) | s420, T424 | |

| Melanoma inhibitory activity protein (MIA3) | s226, s229, S1906 | |

| Endoplasmin (HSP90B1) | S306 | |

| Metal Binding | Serotransferrin (TF) | s389, S685 |

| Ceruloplasmin (CP) | S722 | |

| Other | Protein disulfide isomerase A1 (PDIA1) | S208 |

| Protein disulfide isomerase A6 (PDIA6) | s357 | |

| Plasma alpha-L-fucosidase (FUCA2) | S301 | |

| DnaJ homolog subfamily C member 3 (DNAJC3) | s274 | |

| Protein notum homolog (NOTUM) | S81 | |

| Alpha-1,3-mannosyl-glycoprotein 4-beta-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase A (MGAT4A) | s474 | |

| Syndecan-2 (SDC2) | S115 |

Fam20C is also highly expressed in lactating mammary gland and mineralized tissues; thus, we hypothesized that the landscape of secreted phosphoproteins might be distinct between different cell types. To further explore the contribution of Fam20C to the secreted phosphoproteome, we generated stable Fam20C knockdown (KD) MDA-MB-231 (breast epithelial), U2OS (osteoblast-like) and HepG2 (liver) cells using short hairpin RNA (shRNA), and performed label-free phosphoprotein quantification by means of mass spectrometry (MS) using conditioned medium from control and Fam20C deficient cells (Figure S5A–E and Excel file S2). We identified more than 150 phosphopeptides representing approximately 100 distinct secreted phosphoproteins that markedly decreased in the Fam20C depleted cells (Tables 1 and 2). Several Fam20C substrates were identified in multiple cell lines, whereas most showed cell type specificity (Figure S5F).

Table 2.

Fam20C-dependent phosphosites in secretory pathway proteins from MDA-MB-231 and U2OS cells. Phosphoserines within a Fam20C consensus motif (pS-x-E/pS) are indicated by a lower case “s”. Non pS-x-E/pS sites are indicated by a capital letter (S, T or Y). The asterisk (*) indicates if the protein was confirmed to be a Fam20C substrate in either cell-based or in vitro kinase assays. See also Figure S5 and Excel file S2.

| Function | Protein Name (Gene Symbol) | Phosphosites |

|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-231 Cells | ||

| Lipid binding & homeostasis | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) * | s688 |

| Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 2 (PNPLA2) | S404 | |

| IGFBPs | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP3) * | s201 |

| Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 4 (IGFBP4) | S255 | |

| Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) | s239 | |

| Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 10 (CYR61) | S188 | |

| Cystatins | Cystatin-C (CST3) * | S43 |

| Protease inhibitors & proteases | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 (TIMP1) | S178 |

| Amyloid-like protein2 (APLP2) | s590 | |

| Serine protease 23 (PRSS23) | S109 | |

| Calcium binding and homeostasis | Reticulocalbin-1 (RCN1) | s80 |

| Follistatin-related protein 1 (FSTL1) | s165 | |

| Follistatin-related protein 3 (FSTL3) | s255 | |

| Nucleobindin-1 (NUCB1) * | s369 | |

| Calumenin (CALU) | s77 | |

| Wolframin (WFS1) | T30, s32 | |

| Glucosidase 2 subunit beta (PRKCSH) | s168 | |

| Adhesion | Lactadherin (MFGE8) | s42 |

| Isoform 3 of Mesothelin (MSLN) | s200 | |

| Extracellular matrix | Isoform 15 of Fibronectin (FN1) * | s2475 |

| Isoform 3 of Latent-transforming growth factor beta-binding protein 1 (LTBP1) | s1035 | |

| Bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4) | s91 | |

| Galectin-1 (LGALS1) | S30 | |

| Fibrillin-1 (FBN1) | s2702 | |

| Tenascin (TNC) | s72 | |

| Signaling & ion transport | Growth arrest-specific protein 6 (GAS6) | s71 |

| Interleukin-6 (IL6) * | s81 | |

| Macrophage colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) | T266 | |

| Chordin-like 1 (CHRDL1) | s186 | |

| Melanotransferrin (MFI2) | S462 | |

| Anoctamin-8 (ANO8) | S801 | |

| Other | Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 (CKAP4) | s232 |

| Transmembrane Protein 132A (TMEM132A) | s530 | |

| Fam176A (Protein eva-1 homolog A) (EVA1A) | s114 | |

| Golgi membrane protein (GOLM1) | s309 | |

| Kinectin (KTN1) | S75 | |

| Isoform 2 of matrix-remodeling-associated protein 8 (MXRA8) | s228 | |

| U2OS Cells | ||

| IGFBPs | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 (IGFBP5) * | s116 |

| Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) * | s239 | |

| Protease | Membrane-bound transcription factor site-1 protease (MBTPS1) | S168 |

| Adhesion | Cadherin-2 (CDH2) | s135 |

| Isoform 3 of Mesothelin (MSLN) | s200 | |

| Calcium binding | Follistatin-related protein 3 (FSTL3) | s255 |

| Other | Shisa-5 (SHISA5) | s115 |

Fam20C directly phosphorylates serum, plasma and CSF phosphoproteins

Collectively, our secreted phosphoproteomic analyses of HepG2, MDA-MB-231 and U2OS cells have established that some 80% of secreted phosphoproteins are Fam20C substrates. As mentioned, most phosphoproteins found in blood and CSF are phosphorylated within the Fam20C S-x-E/pS motif (Table S1). To determine if these proteins were genuine Fam20C substrates and corroborate our MS results, we screened ~25 candidate proteins for their ability to be directly phosphorylated by Fam20C in vitro and/or in cells. Recombinant Fam20C efficiently phosphorylated several of the candidate substrates in vitro in a time dependent manner, whereas the inactive Fam20C D478A mutant did not (Figure 4A and B). We also analyzed V5 immunoprecipitates from conditioned medium of mammalian cells co-expressing V5-tagged substrates with either Flag-tagged Fam20C or the D478A mutant. Fam20C, but not the inactive mutant, effectively phosphorylated each of the secreted proteins as judged by their mobility during SDS-PAGE (Figure 4C), or by incorporation of 32P into V5-immunoprecipitates when the cells were metabolically labeled with 32P orthophosphate (Figure 4D).

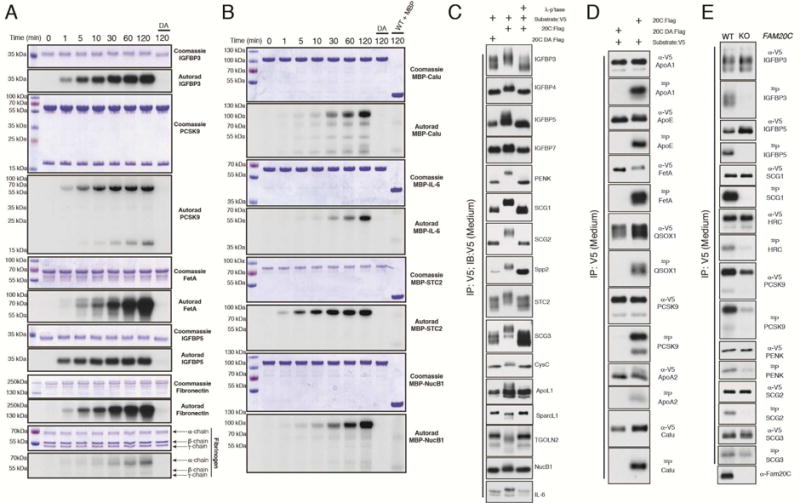

Figure 4. Fam20C directly phosphorylates serum, plasma and CSF proteins.

(A) Time dependent incorporation of 32P from [γ-32P]ATP into IGFBP3, PCSK9, Fetuin A (FetA), IGFBP5, fibronectin, and fibrinogen by Fam20C, or the D478A mutant. Reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE, visualized by Coomassie staining, and radioactivity was detected by autoradiography.

(B) Time dependent incorporation of 32P from [γ-32P]ATP into MBP-tagged calumenin (MBP-Calu), interleukin-6 (MBP-IL-6), stanniocalcin (MBP-STC2) and nucleobindin 1 (MBP-NucB1). MBP was also analyzed as a control for the indicated time point. Reaction products were analyzed as in (A).

(C) Protein immunoblotting of V5-immunoprecipitates from conditioned medium (CM) of U2OS or HEK293T cells co-expressing V5-tagged IGFBP3, IGFBP4, IGFBP5, IGFBP7, proenkephalin (PENK), secretogranin 1 (SCG1), SCG2, secreted phosphoprotein 2 (Spp2), stanniocalcin 2 (STC2), secretogranin 3 (SCG3), cystatin C (CysC), ApoL1, SparcL1, trans Golgi network protein 2 (TGOLN2), NucB1 and IL-6 with WT (20C:Flag) or Fam20C-D478A (20C DA:Flag). V5-immunoprecipitates were treated with λ-phosphatase (λ-p’tase).

(D) Protein immunoblotting and autoradiography of V5-immunoprecipitates from CM of 32P-orthophosphate labeled U2OS cells co-expressing V5-tagged apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1), ApoE, FetA, quiescin Q6 sulfhydryl oxidase 1 (QSOX1), PCSK9, ApoA2, and Calu with 20C:Flag or 20C DA:Flag.

(E) Protein immunoblotting and autoradiography of V5-immunoprecipitates from CM of 32P-orthophosphate labeled control and Fam20C KO U2OS cells expressing V5-tagged IGFBP3, IGFBP5, SCG1, histidine rich calcium binding protein (HRC), PCSK9, PENK, SCG2, and SCG3. Protein immunoblotting of V5-immunoprecipitates from CM (top) and autoradiography depicting 32P incorporation into the V5-tagged substrates (middle). Fam20C protein levels in CM (bottom). See also Table S1.

Furthermore, we expressed V5-tagged proteins in control and Fam20C KO U2OS cells (Tagliabracci et al., 2014) that were metabolically labeled with 32P-orthophosphate and analyzed V5-immunoprecipitates from conditioned medium (Figure 4E). The insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBPs), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type-9 (PCSK9), and several neuropeptide hormone precursor proteins, including proenkephalin (PENK) and the secretogranins, were phosphorylated in control, but not in Fam20C KO cells. Remarkably, Fam20C robustly phosphorylated every substrate tested in vitro and in cells.

Fam20C has broader substrate specificity than previously appreciated

Analysis of the amino acid motifs encompassing the peptide phosphorylation sites in HepG2 cells, revealed that phosphorylation of secreted proteins on Ser residues was by far the most common, followed by Thr and to a lesser extent Tyr (Figure S6A). As expected, the majority of phosphosites that were significantly decreased in Fam20C KO HepG2 cells corresponded to the S-x-E/pS motif (Figure 5A). Surprisingly, we also identified phosphosites that decreased in HepG2 Fam20C KO cells that did not match the Fam20C consensus (Figure S6B). For example, we identified several phosphosites within IGFBP1 that were decreased in Fam20C KO cells, yet did not conform to the S-x-E motif (Figure 5B and Table 1). When expressed in U2OS cells, V5-tagged IGFBP1 was phosphorylated by endogenous Fam20C and overexpressed Flag-tagged Fam20C (Figure 5C, D). Therefore, to determine the sites of phosphorylation on IGFBP1 by Fam20C, we purified recombinant IGFBP1 from insect cells, treated it with WT or D478A Fam20C in vitro, and mapped the resulting phosphosites by MS (Figure 5E and F and Figure S6E and F). Wildtype Fam20C, but not the D478A mutant, phosphorylated several sites on IGFBP1 that did not conform to the S-x-E/pS motif, including Ser45, Thr193 and Ser199. Fam20C was unable however to phosphorylate these residues when synthetic peptides were used as the substrates. These results suggest that Fam20C may require additional factors beyond the primary substrate sequence seen when small peptides are used as substrates. Furthermore, after examining the phosphosites in HepG2, MDA-MB-231 and U2OS cells we did not observe a significant correlation between relative expression of Fam20C and the proportion of substrates that were phosphorylated on residues that did not conform to the S-x-E/pS motif.

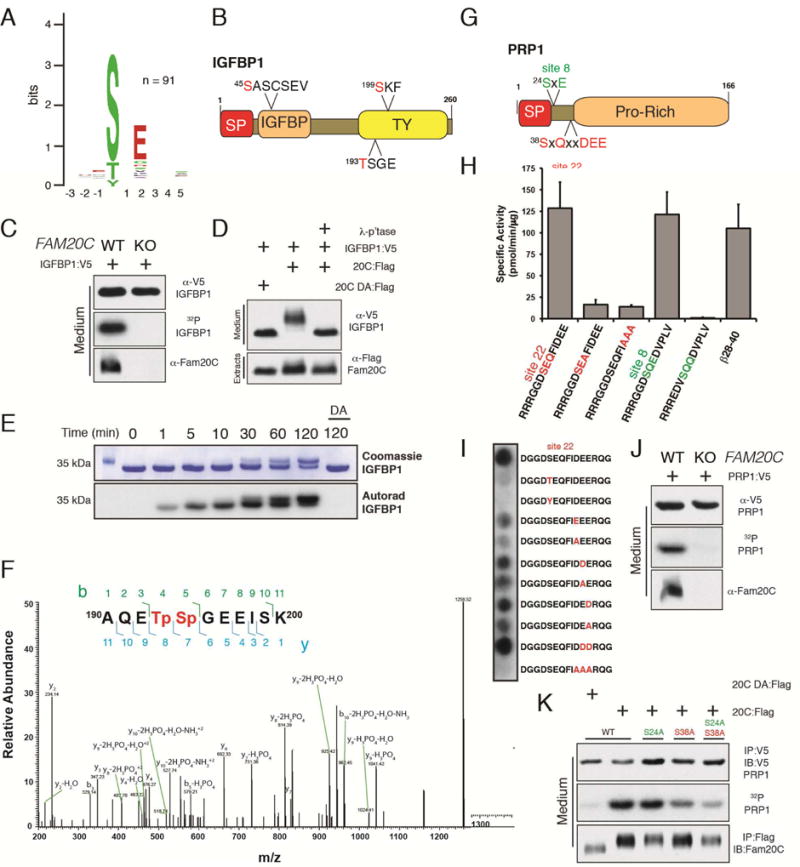

Figure 5. Fam20C exhibits broader substrate specificity than previously appreciated.

(A) Weblogo depicting the phosphopeptides that displayed a significant reduction in Fam20C KO HepG2 cells. The number (n) of phosphopeptides analyzed to generate the Weblogo is shown in the insert.

(B) Schematic representation of IGFBP1 depicting residues (red) whose phosphorylation decreased in Fam20C KO HepG2 cells (SP; signal peptide, TY, Thyroglobulin-1).

(C) Control and Fam20C KO cells were metabolically labeled with 32P-orthophosphate and transfected with V5-tagged IGFBP1. Protein immunoblotting of V5 immunoprecipitates from conditioned medium (CM) (upper) and autoradiography depicting 32P incorporation into the V5-tagged IGFBP1 (middle). Fam20C protein levels in CM are also shown (lower).

(D) Protein immunoblotting of V5 immunoprecipitates from CM of U2OS cells co-expressing V5-tagged IGFBP1 with either WT (20C:Flag) or catalytically inactive D478A (20C DA:Flag). V5-immunoprecipitates were treated with λ-phosphatase (λ-p’tase).

(E) Time dependent incorporation of 32P from [γ-32P]ATP into IGFBP1 by recombinant Fam20C or the D478A mutant. Reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE, visualized by Coomassie staining, and radioactivity was detected by autoradiography.

(F) Representative MS/MS spectrum of a diphosphopeptide identifying phosphorylation of Thr193 and Ser194 on human IGFBP1 after Fam20C treatment. The precursor ion with m/z 669.74 eluted at 5.32 min.

(G) Schematic representation of PRP1 depicting the two phosphoserines (site 8; green and site 22; red).

(H) Recombinant Fam20C was incubated with peptides representing the PRP1 site 8 and 22 Ser residues in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and incorporated radioactivity was quantified by means of scintillation counting. The β28–40 peptide was also analyzed.

(I) A peptide representing the PRP1 site 22 Ser was synthesized and used to further assess the specificity determinants for Fam20C. Incorporation of phosphate was monitored by autoradiography.

(J) Control and Fam20C KO cells were metabolically labeled with 32P-orthophosphate and transfected with V5-tagged PRP1. Protein immunoblotting of V5 immunoprecipitates from CM (upper) and autoradiography depicting 32P incorporation into PRP1 (middle). Fam20C protein levels in CM are also shown (lower).

(K) Protein immunoblotting and autoradiography of V5-immunoprecipitates from CM of 32P-orthophosphate labeled U2OS cells co-expressing V5-tagged PRP1 or the site 8 and 22 Ala mutants with either WT (20C:Flag) or Fam20C-D478A (20C DA:Flag).

See also Figure S6

Our findings are consistent with previous work using peptides derived from proline rich phosphoprotein 1 (PRP1), which demonstrated that the Golgi casein kinase, later identified as Fam20C, could phosphorylate a S-x-Q-x-x-D-E-E motif. (Figure 5G) (Brunati et al., 2000). This activity required the Q at the +2 position and the three acidic residues at the +5, +6 and +7 positions. Fam20C also phosphorylated this Ser in vitro using a synthetic peptide as substrate (Figure 5H and I) and in cells when PRP1 was expressed as a V5-tagged fusion protein (Figure 5J and K). As anticipated, Fam20C required the Q at the n+2 position and acidic residues at the +5, +6 and +7 positions. Analysis of the C. elegans Fam20C crystal structure revealed several conserved basic residues that were proposed to interact with these downstream acidic residues (Xiao et al., 2013). Collectively, these results demonstrate that Fam20C can recognize amino acid sequences in addition to the canonical S-x-E/pS motif and suggest that Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation is more extensive than indicated solely by those substrates phosphorylated within the canonical recognition sequence.

GO Term analysis of Fam20C substrates reveals an unexpected role for secreted protein phosphorylation in cell adhesion, migration and invasion

Human FAM20C mutations cause Raine syndrome, an osteosclerotic bone dysplasia (Raine et al., 1989; Simpson et al., 2007). The defects in bone formation in Raine patients underscore the importance of Fam20C dependent phosphorylation of secreted proteins, such as the SIBLINGs, for the process of tissue mineralization. However, Fam20C is likely to have additional physiological functions because it is ubiquitously expressed, conserved in organisms that do not have mineralized tissues (Nalbant et al., 2005; Tagliabracci et al., 2013b; Wang et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2013), and most Fam20C substrates identified in this work have no apparent link to biomineralization. Gene ontology (GO) term analysis using the DAVID server (Huang da et al., 2009) showed that biological processes, such as wound healing, lipid homeostasis, endopeptidase inhibitor activity, cell adhesion and cell migration, were enriched in the Fam20C-regulated gene set (Figure 6A Excel file S3). To establish whether Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation of extracellular proteins promotes cell adhesion and migration, the FAM20C gene was disrupted by means of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in MDA-MB-231 cells, a highly invasive breast cancer cell line (Figure S7). We initially analyzed the ability of Fam20C KO cells to adhere to culture dishes by monitoring cell detachment. Cells depleted of Fam20C had altered adhesive properties as judged by their resistance to detach in the presence of phosphate buffered EDTA (Figure 6B). We then monitored cell migration in scratch wound-healing experiments and demonstrated that Fam20C KO cells were also severely impaired in their ability to migrate when compared to control cells (Figure 6C). Furthermore, depletion of Fam20C largely blocked the ability of these cells to migrate in trans-well chemotaxis and 2D matrigel invasion assays (Figure 6D and E). These results support that Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation of secreted proteins is necessary for the proper adhesion, migration and invasion of breast cancer cells.

Figure 6. GO term analysis of Fam20C substrates reveals an unexpected role for secreted protein phosphorylation in cell adhesion, migration and invasion.

(A) DAVID GO term analysis using the HepG2 Fam20C-regulated gene set. The graph represents the statistically significant enriched gene clusters with the number of genes in each cluster indicated beside the bars.

(B) Bar graph depicting cell detachment in a cell adhesion assay using WT and Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells. Data report detached cells (% of total) after 10 min treatment with PBS-buffered EDTA and represent the mean (+/− SD) of 10 replicates in two independent experiments (*** p ≤ 0.0001 vs WT).

(C) Bar graph depicting cell migration (area of wound covered) in a scratch wound-healing assay using WT and Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells. Data was acquired 7 and 20 hours after the scratch and represents the mean (+/− SD) of three independent experiments (*** p ≤ 0.0001 vs WT).

(D) Bar graph depicting cell migration/chemotaxis in a trans-well migration assay using WT and Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells. Medium with 10% FBS was used as a chemoattractant. Data was acquired 24 hours after seeding in upper chamber of 8 μm pore size trans-wells and is expressed as average number of cells/field (+/− SD) from 3 independent experiments (* p<0.05 vs WT).

(E) Bar graph depicting cell migration/invasion in a Matrigel trans-well migration assay using control and Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells. Data was acquired 24 hours after seeding in upper chamber of 8 μm pore size trans-wells. Cells that invaded the Matrigel were quantified based on DNA content using CyQuant dye and normalized to WT. Data represent mean (+/− SD) from 3 independent experiments (*** p ≤ 0.0001 vs WT).

(F) Bar graph depicting cell migration (area of wound covered) in a scratch wound-healing assay using WT and Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were incubated in SFM or conditioned medium (CM) from Fam20C WT or KO MDA-MB-231 cells as indicated during wound-healing. Data was acquired 6 hours after the scratch and depicts mean (+/− SD) from a representative experiment performed in triplicate (***p = 0.0002 vs WT, **p = 0.0025 vs KO).

(G) Workflow used to screen candidate Fam20C substrates in the scratch-wound healing assay shown in Figure 6H.

(H) Bar graph depicting cell migration (area of wound covered) in a scratch wound-healing assay using WT and Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were incubated in SFM or CM from U2OS cells that were transfected with either vector (Control), IGFBP7-V5 + WT Fam20C (pIGFBP7), or IGFBP7-V5 + D478A Fam20C (IGFBP7) as indicated during the wound-healing. Data was acquired 6 hours after the scratch and shows mean (+/− SD) of a representative experiment performed in triplicate (*p = 0.0146 vs IGFBP7, **p < 0.0001, ***p = 0.0098 vs KO). An immunoblot of V5-immunoprecipitates from the CM of U2OS cells used in the rescue experiments is shown in the insert.

See also Figure S7

To test whether phosphoproteins in conditioned medium from WT cells could rescue the migration defects in Fam20C deficient cells, we performed a media swap experiment. When Fam20C KO cells were cultured in serum free conditioned medium from WT cells, the Fam20C KO cell migration phenotype was rescued; demonstrating that Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation of soluble, secreted proteins promotes cell migration (Figure 6F). To identify secreted phosphoproteins whose phosphorylation can stimulate MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell migration, we developed a cell-based assay to screen candidate Fam20C substrates for their ability to rescue the cell migration defects in Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 6G). We cultured Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells in serum free conditioned medium collected from U2OS cells that were coexpressing WT or D478A Fam20C with some 20-candidate V5-tagged substrates and performed scratch wound-healing experiments. Most Fam20C substrates had little effect on cell migration in the Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells. Furthermore, the presence of WT or inactive Fam20C in the conditioned medium did not affect cell migration. We did however observe a significant increase in cell migration when the Fam20C KO cells were cultured in medium containing phosphorylated, but not unphosphorylated, IGFBP7 (Figure 6H). As their name implies, the IGFBP’s bind IGF-1; however, we did not detect IGF-1 protein in conditioned medium of MDA-MB-231 or U2OS cells (Excel file S2). Therefore, we conclude that phosphorylated IGFBP7 promotes cell migration in an IGF-1 independent manner. Indeed, there are several reports describing IGF-1-independent functions for the IGFBP’s (Baxter, 2014). Collectively, these results suggest that Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation of IGFBP7 contributes to breast cancer cell migration.

Discussion

Although numerous secreted proteins and peptide hormones are phosphorylated, the molecular identities of the kinases responsible for these modifications have only recently been identified (Bordoli et al., 2014; Ishikawa et al., 2008; Tagliabracci et al., 2012; Tagliabracci et al., 2013a). Our knowledge about these enzymes is in its infancy and extracellular protein phosphorylation will likely emerge as a fundamental mechanism that regulates many physiological processes. Nearly 60 years of protein phosphorylation research have uncovered many functions for intracellular phosphorylation and there is no reason to believe these mechanisms will be any different for protein phosphorylation that takes place in the ER/Golgi lumen or outside the cell.

David GO term analysis showed that biological processes, including wound healing, lipid homeostasis, endopeptidase inhibitor activity, and cell adhesion and migration, were enriched in the Fam20C-regulated gene set (Figure 6A and Excel file S3). Substantiating these observations, Fam20C MDA-MB-231 KO cells did not detach as readily as WT cells and displayed a significant reduction in their ability to migrate in scratch-wound healing and chemotaxis migration assays. Furthermore, Fam20C appears to be necessary for these cells to invade matrigel coated transwells, a process largely dependent on extracellular protease activity. Numerous Fam20C substrates have been implicated in tumor growth and metastasis, including the IGFBPs (Baxter, 2014), OPN (Bellahcene et al., 2008), several extracellular proteases and the serine protease inhibitors (Serpins) (Valiente et al., 2014). Therefore, loss of phosphorylation of multiple Fam20C substrates could contribute to the cell motility defects in Fam20C deficient breast cancer cells. We discovered that phosphorylated IGFBP7 was able to largely rescue the cell migration defects in MDA-MB-231 cells that were depleted of Fam20C (Figure 6H). The molecular mechanism(s) by which Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation of IGFBP7 potentiates cell migration are currently unknown. However, both the IGFBP7 and the FAM20C gene are amplified or overexpressed in human cancers (Bieche et al., 2004; Cerami et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013; Georges et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2008).

Interestingly, a recent analysis of the phosphoprotein secretome of tumor cells and patient plasma has uncovered candidates for breast cancer biomarkers, including IGFBP3, IGFBP5, OPN, follistatin-like 3, stanniocalcin-2, and cystatin C. (Zawadzka et al., 2014). Virtually every phosphopetide identified was phosphorylated within the Fam20C consensus S-x-E recognition motif. Indeed, we also identified all of these proteins as Fam20C substrates in this study. Thus, inhibition of Fam20C may be a viable therapeutic strategy to prevent tumor cell progression and metastasis.

Many Fam20C substrates have been implicated in other human diseases, and missense mutations within or surrounding Fam20C-dependent S-x-E phosphorylation sites have been identified. For example, we identified Ser47 on PCSK9, a protease implicated in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol metabolism, as a Fam20C-regulated phosphosite (Table 1). A missense mutation of a potential protease cleavage site in PCSK9 adjacent to Ser47 (Arg46Leu) leads to low plasma levels of LDL cholesterol (Dewpura et al., 2008; Kotowski et al., 2006). This is notable because we have previously shown that Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation of FGF23 regulates its proteolytic cleavage and has important implications in phosphate homeostasis (Tagliabracci et al., 2014).

We have also identified Ser91 on bone morphogenic protein-4 (BMP4) as a Fam20C-dependent phosphosite (Tables 1 and 2). BMP4 is a member of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily and controls cellular proliferation and differentiation. In humans, missense mutations of BMP4 on Ser91 and Glu93 cause renal hypodysplasia and anophthalmia-micropthalmia (Bakrania et al., 2008; Weber et al., 2008). Both of these sites fall within the 91S-G-E93 motif, and the mutations would be predicted to disrupt Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation. This is reminiscent of what has been observed with the enamel matrix protein enamelin, where loss of Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation of a 216S-x-E218 motif, caused by a Ser216Leu mutation, is sufficient to cause amelogenesis imperfecta (Chan et al., 2010).

The results of this study expand our understanding on the rapidly developing field of extracellular protein phosphorylation by kinases in the secretory pathway and the extracellular space. We identified over 100 secreted proteins as Fam20C substrates and have established Fam20C as the major secretory pathway protein kinase. Our work opens new areas of research on extracellular protein phosphorylation in human biology and disease.

Experimental Procedures

Additional procedures can be found in the Supplemental Information under Extended Supplemental Procedures.

Kinase assays

In vitro kinase assays using protein and peptide substrates were performed as described (Tagliabracci et al., 2012). PRP1 site 22 peptides were synthesized on derivatized cellulose membranes and used in kinase assays as described in (Tagliabracci et al., 2012).

Arrayed Positional Scanning Peptide Library

A Ser/Thr peptide library set consisting of 198 biotinylated substrates was purchased from Anaspec and assayed as described (Chen and Turk, 2010).

Detachment, scratch-wound and trans-well migration assays

The detachment assay was performed as described with minor modifications (Gagnoux-Palacios et al., 2001) and quantified using the fluorescent CyQuant DNA-binding dye (Life Technologies). The scratch wound-healing assay was performed as previously described (O’Neill et al., 2011). WT and Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells were grown to confluence, the monolayer was scratched with a pipet tip, and the cells were imaged at 0 hr and various time points post-scratch. The area migrated was quantified. For the IGFBP7 media swap experiments, U2OS cells were transfected with either vector, IGFBP7-V5 + D478A-Fam20C, or IGFBP7-V5 + WT-Fam20C, followed by incubation for 30 hr in SFM to generate conditioned media that was applied to MDA-MB-231 cells post-scratch. The trans-well chemotaxis migration assay was performed using 8 μm pore size transwells following standard protocols. The bottom chamber contained normal growth media (DMEM with 10% FBS) as a chemoattractant. WT or Fam20C KO MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded into the upper chamber (20,000 cells/insert) in SFM. After 24 hr of culture, cells that migrated through the pores were imaged and quantified. Matrigel invasion assays were performed similarly as above and as previously described (Sodek et al., 2008); trans-well inserts were coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) before seeding cells.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Fam20C is unique amongst the known secretory pathway kinases.

Fam20C generates the majority of the secreted phosphoproteome.

Fam20C substrates are implicated in a broad spectrum of biological processes.

Fam20C is crucial for proper adhesion, migration and invasion of breast cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Taylor, Carolyn Worby, Peter van der Geer, and Jenna Jewell for valuable input. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK018849-36 and DK018024-37 to J.E.D, K99DK099254 to V.S.T., R01DK098672 to D.J.P., GM094575 to N.V.G.), the Welch Foundation (I-1505 to N.V.G.), and the AIRC (IG 10312 to L.A.P.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

V.S.T., S.E.W., and J.E.D, designed the experiments. V.S.T., S.E.W., E.D., J.W., J.X., J.C., K.B.N., and J.L.E. performed the experiments. X.G. J.J.C. and D.J.P performed the mass spectrometry. L.N. and N.G. performed the bioinformatics. L.A.P. provided valuable reagents. V.S.T., S.E.W. and J.E.D wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

References

- Aziz A, Harrop SP, Bishop NE. Characterization of the deleted in autism 1 protein family: implications for studying cognitive disorders. PLoS One. 2011a;6:e14547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz A, Harrop SP, Bishop NE. DIA1R is an X-linked gene related to Deleted In Autism-1. PLoS One. 2011b;6:e14534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahl JM, Jensen SS, Larsen MR, Heegaard NH. Characterization of the human cerebrospinal fluid phosphoproteome by titanium dioxide affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008;80:6308–6316. doi: 10.1021/ac800835y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakrania P, Efthymiou M, Klein JC, Salt A, Bunyan DJ, Wyatt A, Ponting CP, Martin A, Williams S, Lindley V, et al. Mutations in BMP4 cause eye, brain, and digit developmental anomalies: overlap between the BMP4 and hedgehog signaling pathways. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:304–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter RC. IGF binding proteins in cancer: mechanistic and clinical insights. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:329–341. doi: 10.1038/nrc3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellahcene A, Castronovo V, Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLINGs): multifunctional proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:212–226. doi: 10.1038/nrc2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieche I, Lerebours F, Tozlu S, Espie M, Marty M, Lidereau R. Molecular profiling of inflammatory breast cancer: identification of a poor-prognosis gene expression signature. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10:6789–6795. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordoli MR, Yum J, Breitkopf SB, Thon JN, Italiano JE, Jr, Xiao J, Worby C, Wong SK, Lin G, Edenius M, et al. A secreted tyrosine kinase acts in the extracellular environment. Cell. 2014;158:1033–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunati AM, Marin O, Bisinella A, Salviati A, Pinna LA. Novel consensus sequence for the Golgi apparatus casein kinase, revealed using proline-rich protein-1 (PRP1)-derived peptide substrates. Biochem J 351 Pt. 2000;3:765–768. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrascal M, Gay M, Ovelleiro D, Casas V, Gelpi E, Abian J. Characterization of the human plasma phosphoproteome using linear ion trap mass spectrometry and multiple search engines. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:876–884. doi: 10.1021/pr900780s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HC, Mai L, Oikonomopoulou A, Chan HL, Richardson AS, Wang SK, Simmer JP, Hu JC. Altered enamelin phosphorylation site causes amelogenesis imperfecta. J Dent Res. 2010;89:695–699. doi: 10.1177/0022034510365662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Turk BE. Analysis of serine-threonine kinase specificity using arrayed positional scanning peptide libraries. In: Ausubel Frederick M., editor. Current protocols in molecular biology. 2010. Chapter 18, Unit 18 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewpura T, Raymond A, Hamelin J, Seidah NG, Mbikay M, Chretien M, Mayne J. PCSK9 is phosphorylated by a Golgi casein kinase-like kinase ex vivo and circulates as a phosphoprotein in humans. FEBS J. 2008;275:3480–3493. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudkiewicz M, Lenart A, Pawlowski K. A novel predicted calcium-regulated kinase family implicated in neurological disorders. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnoux-Palacios L, Allegra M, Spirito F, Pommeret O, Romero C, Ortonne JP, Meneguzzi G. The short arm of the laminin gamma2 chain plays a pivotal role in the incorporation of laminin 5 into the extracellular matrix and in cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:835–850. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges RB, Adwan H, Hamdi H, Hielscher T, Linnemann U, Berger MR. The insulin-like growth factor binding proteins 3 and 7 are associated with colorectal cancer and liver metastasis. Cancer biology & therapy. 2011;12:69–79. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.1.15719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarsten O. Zur Frage ob Caseín ein einheitlicher Stoff sei. Hoppe-Seyler’s Zeitschrift für Physiologische Chemie. 1883:227–273. [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutti JE, Jarrell ET, Chang JD, Abbott DW, Storz P, Toker A, Cantley LC, Turk BE. A rapid method for determining protein kinase phosphorylation specificity. Nat Methods. 2004;1:27–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa HO, Takeuchi H, Haltiwanger RS, Irvine KD. Four-jointed is a Golgi kinase that phosphorylates a subset of cadherin domains. Science. 2008;321:401–404. doi: 10.1126/science.1158159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa HO, Xu A, Ogura E, Manning G, Irvine KD. The Raine syndrome protein FAM20C is a Golgi kinase that phosphorylates biomineralization proteins. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jae LT, Raaben M, Riemersma M, van Beusekom E, Blomen VA, Velds A, Kerkhoven RM, Carette JE, Topaloglu H, Meinecke P, et al. Deciphering the glycosylome of dystroglycanopathies using haploid screens for lassa virus entry. Science. 2013;340:479–483. doi: 10.1126/science.1233675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Xiang C, Cazacu S, Brodie C, Mikkelsen T. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 mediates glioma cell growth and migration. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1335–1342. doi: 10.1593/neo.08694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike T, Izumikawa T, Tamura J, Kitagawa H. FAM20B is a kinase that phosphorylates xylose in the glycosaminoglycan-protein linkage region. Biochem J. 2009;421:157–162. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotowski IK, Pertsemlidis A, Luke A, Cooper RS, Vega GL, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. A spectrum of PCSK9 alleles contributes to plasma levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:410–422. doi: 10.1086/500615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasa-Benito M, Marin O, Meggio F, Pinna LA. Golgi apparatus mammary gland casein kinase: monitoring by a specific peptide substrate and definition of specificity determinants. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:149–152. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg I, Pang HW, Stains JP, Clark D, Yang AJ, Bonewald L, Li KZ. FGF23 is endogenously phosphorylated in bone cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meggio F, Perich JW, Meyer HE, Hoffmann-Posorske E, Lennon DP, Johns RB, Pinna LA. Synthetic fragments of beta-casein as model substrates for liver and mammary gland casein kinases. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:459–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok J, Kim PM, Lam HY, Piccirillo S, Zhou X, Jeschke GR, Sheridan DL, Parker SA, Desai V, Jwa M, et al. Deciphering protein kinase specificity through large-scale analysis of yeast phosphorylation site motifs. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow EM, Yoo SY, Flavell SW, Kim TK, Lin Y, Hill RS, Mukaddes NM, Balkhy S, Gascon G, Hashmi A, et al. Identifying autism loci and genes by tracing recent shared ancestry. Science. 2008;321:218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1157657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbant D, Youn H, Nalbant SI, Sharma S, Cobos E, Beale EG, Du Y, Williams SC. FAM20: an evolutionarily conserved family of secreted proteins expressed in hematopoietic cells. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill AK, Gallegos LL, Justilien V, Garcia EL, Leitges M, Fields AP, Hall RA, Newton AC. Protein kinase Calpha promotes cell migration through a PDZ-dependent interaction with its novel substrate discs large homolog 1 (DLG1) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43559–43568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.294603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine J, Winter RM, Davey A, Tucker SM. Unknown syndrome: microcephaly, hypoplastic nose, exophthalmos, gum hyperplasia, cleft palate, low set ears, and osteosclerosis. J Med Genet. 1989;26:786–788. doi: 10.1136/jmg.26.12.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson MA, Hsu R, Keir LS, Hao J, Sivapalan G, Ernst LM, Zackai EH, Al-Gazali LI, Hulskamp G, Kingston HM, et al. Mutations in FAM20C are associated with lethal osteosclerotic bone dysplasia (Raine syndrome), highlighting a crucial molecule in bone development. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:906–912. doi: 10.1086/522240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodek KL, Brown TJ, Ringuette MJ. Collagen I but not Matrigel matrices provide an MMP-dependent barrier to ovarian cancer cell penetration. BMC cancer. 2008;8:223. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabracci VS, Engel JL, Wen J, Wiley SE, Worby CA, Kinch LN, Xiao J, Grishin NV, Dixon JE. Secreted kinase phosphorylates extracellular proteins that regulate biomineralization. Science. 2012;336:1150–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.1217817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabracci VS, Engel JL, Wiley SE, Xiao J, Gonzalez DJ, Nidumanda Appaiah H, Koller A, Nizet V, White KE, Dixon JE. Dynamic regulation of FGF23 by Fam20C phosphorylation, GalNAc-T3 glycosylation, and furin proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5520–5525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402218111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabracci VS, Pinna LA, Dixon JE. Secreted protein kinases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013a;38:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabracci VS, Xiao J, Dixon JE. Phosphorylation of substrates destined for secretion by the Fam20 kinases. Biochemical Society transactions. 2013b;41:1061–1065. doi: 10.1042/BST20130059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant-Eyles AJ, Moffitt H, Whitehouse CA, Roberts RG. Characterisation of the FAM69 family of cysteine-rich endoplasmic reticulum proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406:471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente M, Obenauf AC, Jin X, Chen Q, Zhang XH, Lee DJ, Chaft JE, Kris MG, Huse JT, Brogi E, et al. Serpins promote cancer cell survival and vascular co-option in brain metastasis. Cell. 2014;156:1002–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Renesse A, Petkova MV, Lutzkendorf S, Heinemeyer J, Gill E, Hubner C, von Moers A, Stenzel W, Schuelke M. POMK mutation in a family with congenital muscular dystrophy with merosin deficiency, hypomyelination, mild hearing deficit and intellectual disability. J Med Genet. 2014;51:275–282. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-102236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang S, Li C, Gao T, Liu Y, Rangiani A, Sun Y, Hao J, George A, Lu Y, et al. Inactivation of a novel FGF23 regulator, FAM20C, leads to hypophosphatemic rickets in mice. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S, Taylor JC, Winyard P, Baker KF, Sullivan-Brown J, Schild R, Knuppel T, Zurowska AM, Caldas-Alfonso A, Litwin M, et al. SIX2 and BMP4 mutations associate with anomalous kidney development. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2008;19:891–903. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Xiao J, Rahdar M, Choudhury BP, Cui J, Taylor GS, Esko JD, Dixon JE. Xylose phosphorylation functions as a molecular switch to regulate proteoglycan biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:15723–15728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417993111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Tagliabracci VS, Wen J, Kim SA, Dixon JE. Crystal structure of the Golgi casein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10574–10579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309211110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida-Moriguchi T, Willer T, Anderson ME, Venzke D, Whyte T, Muntoni F, Lee H, Nelson SF, Yu L, Campbell KP. SGK196 is a glycosylation-specific O-mannose kinase required for dystroglycan function. Science. 2013;341:896–899. doi: 10.1126/science.1239951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida-Moriguchi T, Willer T, Anderson ME, Venzke D, Whyte T, Muntoni F, Lee H, Nelson SF, Yu L, Campbell KP. Phosphoprotein secretome of tumor cells as a source of candidates for breast cancer biomarkers in plasma. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:1034–1049. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Ross MM, Tessitore A, Ornstein D, Vanmeter A, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF., 3rd An initial characterization of the serum phosphoproteome. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:5523–5531. doi: 10.1021/pr900603n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.