Abstract

The tumor microenvironment plays an essential role in various stages of cancer development. This environment, composed of the extracellular matrix, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and cells of the immune system regulates the behavior of and co-evolve with tumor cells. Many of the components, including the innate and adaptive immune cells, play multifaceted roles during cancer progression and can promote or inhibit tumor development, depending on local and systemic conditions. Interestingly, a strategy by which tumor cells gain drug resistance is by modifying the tumor microenvironment. Together, understanding the mechanisms by which the tumor microenvironment functions should greatly facilitate the development of new therapeutic interventions by targeting the tumor niche.

Keywords: Adaptive immunity, carcinoma-associated fibroblasts, chemoresistance, exosomes microvesicles, extracellular matrix, innate immunity, matrix metalloproteinases, tumor microenvironment

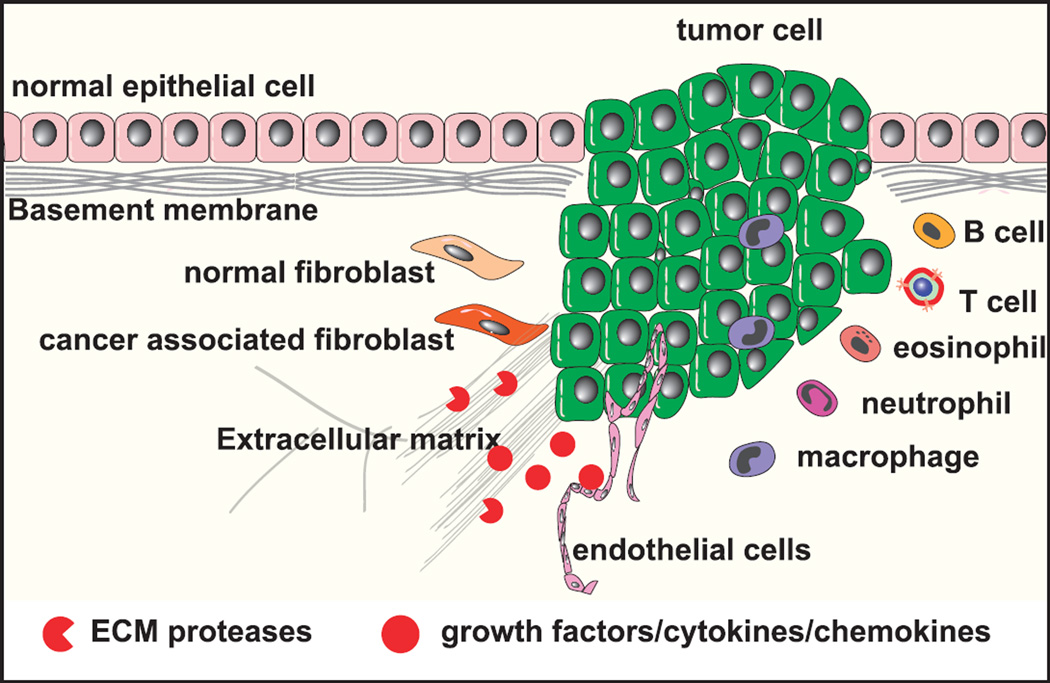

The stroma consists of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is composed of proteoglycans, hyaluronic acid, and fibrous proteins such as collagen, fibronectin, and laminin; growth factors, chemokines, cytokines, antibodies, and metabolites; and mesenchymal supporting cells (e.g., fibroblasts and adipocytes), cells of the vascular system, and cells of the immune system (Fig. 1). As tumors develop, the stroma also evolves.1–6

FIGURE 1.

Composition of the tumor stromal microenvironment. The stroma consists of ECM, including proteoglycans, hyaluronic acid, and fibrous proteins such as collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, and stromal cells (e.g., fibroblasts and adipocytes); cells of the vascular system; and cells of the immune system.

COMPOSITION OF THE STROMA

Cancer cells produce factors that activate and recruit carcinoma-associated fibroblasts, which are an activated fibroblast subtype (myofibroblasts).7 Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts resemble mesenchymal progenitors or embryonic fibroblasts8 and are able to stimulate cancer cell growth and invasion as well as inflammation and angiogenesis.7,9,10 In some systems, they may also be tumor inhibiting.7,11 Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts activated by the tumor microenvironment are largely responsible for tumor-associated changes in the ECM including increased ECM synthesis and remodeling of ECM proteins by proteinases, for example, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).12,13 The altered ECM then influences tumor progression by architectural and signaling interactions.14

Several ECM proteins such as tenascin C and an alternatively spliced version of fibronectin expressed embryonically during organ development are re-expressed during tumor progression.15 Fibrillar type I collagen also increases in tumors.16 Fragments of type I collagen or laminin 332 produced as a result of MMP cleavage may be tumor promoting by stimulating cellular migration and survival.17,18 The biophysical characteristics of tissues, such as stiffness, may affect cellular function. Mammary epithelial cells cultured in compliant collagen matrices form polarized acini, whereas in rigid matrices, they lose polarity and become proliferative and invasive.4,19

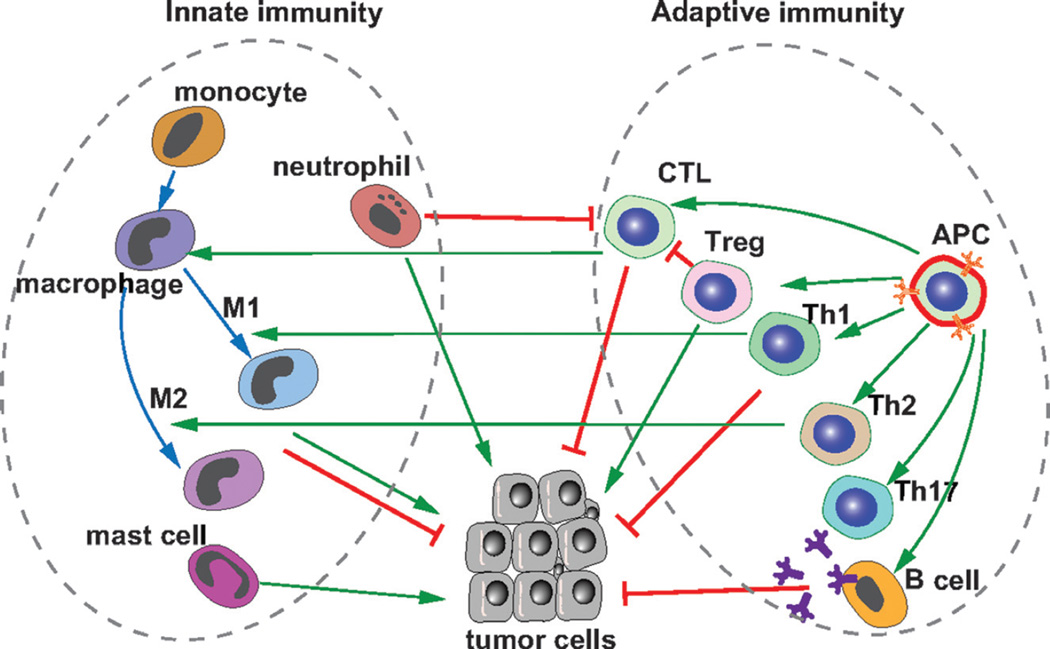

Inflammatory responses are associated with many cancers and may facilitate tumor progression.20 Both adaptive and innate immune cells infiltrate into tissues and are critical players.21–25 Whereas the innate immune compartment is primarily tumor promoting, the adaptive immune compartment (B and T cells) can be tumor suppressing.

The adaptive immune compartment (B and T cells) carries out immune surveillance, keeping initiated cancer cells in check.22,26 Indeed, patients with a suppressed adaptive immune system have an increased risk of developing cancers.27 CD4+ T cells are key regulators of the immune system and differentiate into various T-helper cell lineages: interferon γ–producing TH1 cells that promote cell-mediated immunity and interleukin 4 (IL-4)–producing T helper 2 (TH2) cells that support humoral immune responses.28 Both TH1 and TH2 cells can enhance antitumor immunity by expanding the cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell (CTC) population. In contrast, regulatory T (Tregs) cells suppress antitumor immunity by inhibiting cytotoxic T cells. TH17 cells secrete IL-17. Whereas TH1 cells are primarily antitumor, TH2 cells promote tumors through their cytokines, which polarize tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to promote cancer progression.21 CD4+ Tregs are immune suppressive, directly suppressing antitumor immunity of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells via secretion of IL-10 and transforming growth factor β. Depletion of Tregs enhances tumor growth.28 CD4+ TH17 cells play roles in inflammation and tumor immunity.29 TH17 cells develop from naive CD4+ T cells in the presence of transforming growth factor β, IL-6, and IL-1β. Whether TH17 cells adopt a protumorigenic or anti-tumorigenic role depends on the stimuli encountered by the cells.

Myeloid-derived innate cells (e.g., macrophages, neutrophils, and mast cells) are largely responsible for inflammatory reactions (Fig. 2). Monocytes are polarized to M1 macrophages by cytokines secreted from TH1 cells such as interferon γ, tumor necrosis factor α, and granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor; produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates and inflammatory cytokines; and are antitumor.30,31 In contrast, monocytes exposed to cytokines secreted from TH2 cells such as IL-4 and IL-13 become polarized toward the M2 macrophage phenotype. However, this classification does not accurately define the differentiated state of macrophages exposed to the complex in vivo environments. Tumor-associated macrophages mostly resemble M2 macrophages. Accumulation of TAMs is associated with poor prognosis.32,33

FIGURE 2.

Multifaceted roles of innate and adaptive immunity in cancer development. Whereas adaptive immunity, including T and B cells, is essential for inhibiting cancer development, innate immunity, including neutrophils, macrophages, and mast cells, may promote or inhibit cancer development depending on the local and systemic contexts. For example, macrophages can be polarized and activated by cytokines secreted by TH1 cells and produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates and inflammatory cytokines. These proinflammatory M1 macrophages can inhibit tumorigenesis; by contrast, TAMs (or M2 anti-inflammatory) polarized by cytokines secreted from TH2 cells are associated with poor prognosis. Regulatory T cells can inhibit cytotoxic T-cell function and thus promote tumorigenesis.

Neutrophils can inhibit or promote cancer development.24,34 With increased tumor burden, activated neutrophils accumulate in bone marrow, spleen, and peripheral blood and, at the invasive tumor front,24,35,36 promote cancer metastasis by inhibiting cytotoxic T cells and promoting angiogenesis. Mast cells can also drive tumor progression.37,38

Recruiting vasculature is a critical step in tumor development. Tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived cells are major sources of proangiogenic factors.39,40 These myeloid cells also regulate the resistance of tumors to antiangiogenic therapy.41

TUMOR-REGULATING MICROENVIRONMENTS

Tumors have specialized niches, or microenvironments regulate functions of the cancer cells. Genes involved in regulation of stem cell niches also play a role in cancer.42,43 Like stem cell–like niches that require Wnt signaling for self-renewal of intestinal stem cells, activation of the Wnt pathway by inactivating mutations in the APC gene results in colorectal cancers.44 Alteration of the microenvironment through genetic mutation in SMAD4 in the stroma also results in gastrointestinal epithelial cancer.45

How the microenvironment directs tumor development is just beginning to be elucidated. One clue is that the percentage of cancer cells that express stem cell or basal markers increases when the cells are grown on type I collagen.46,47 Moreover, invasive cells are often associated with fibrillar collagen in vivo,47 and cancer stem-like cells may be enriched at the invasive front where the highest levels of type I collagen are found.48

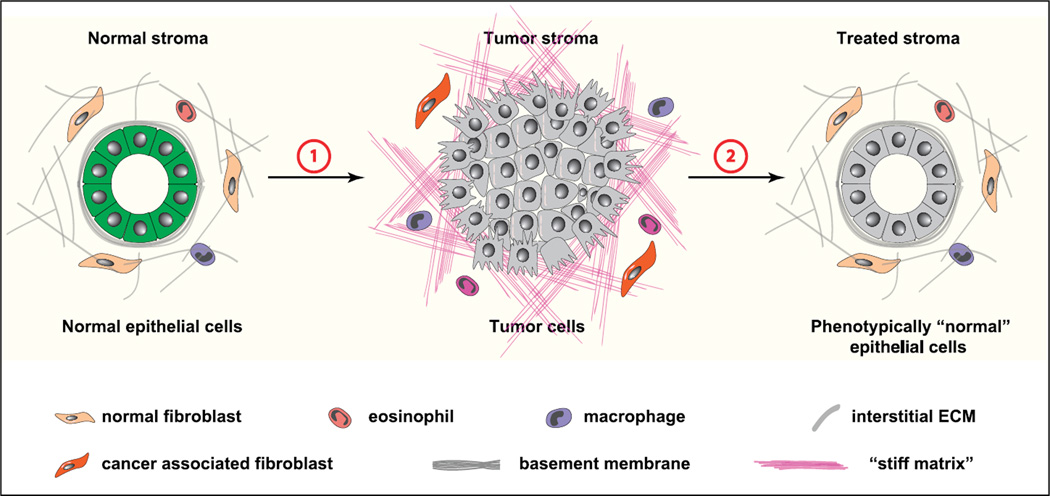

Certain microenvironments can restrict tumor progression. In the presence of a basement membrane–like matrix, breast tumor cells behave more like normal epithelial cells.14 Antibodies to β1 integrins that increase in malignant cells can normalize the malignant phenotype of cancer cells both in culture and in vivo.49 In essence, ECM molecules that maintain normal tissue architecture and cancer cells quiescence may be tumor suppressors (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Targeting stroma in cancer therapeutics. Changes in the stromal microenvironment are an important aspect of cancer evolution. Tumor stroma undergoes concurrent changes with cancer cells and plays a causative role during initiation, progression, and metastasis of cancer development (1). In addition to promoting cancer development, tumor stroma is a major barrier to cancer drugs and plays a role in drug resistance. Importantly, forceful reversion of cancer stroma to the normal state restores normal behavior to cancer cells (2). As such, tumor stroma is a promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment.

The organ specificity of metastasis correlates with specific gene expression of the disseminating cancer cells.50 This raises the question of whether the specific organ microenvironments are matched to specific needs of cancer cells. Moreover, primary tumors alter the distant microenvironmental niches through secreted factors and exosomes, making them more amenable for colonization.24,51,52 Because exosomes and other microvesicles may be taken up in a cell-specific manner, they may be involved in selecting specific metastatic sites.53

THE TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT AND RESPONSE TO CHEMOTHERAPY

The tumor microenvironment is critical in the response chemotherapy.54 Cancer cells may be more distant from blood vessels, impairing drug penetration. Tumors may have incompetent blood vessels and decreased lymphatics, resulting in increased interstitial fluid pressure, which inhibits diffusion of drugs into the tumor. The properties of the microenvironment including ECM composition and hypoxia may alter the phenotype of the tumor cells, resulting in decreased drug uptake. This raises the question of whether chemoresistance may be overcome by targeting the microenvironment. Altering vascular permeability by affecting MMPs may increase drug delivery.55,56 Blocking fibroblast activating protein, which is made by carcinoma-associated fibroblasts, results in reduced type I collagen and improved drug delivery.57

PERSPECTIVES

Components of the tumor microenvironment contribute to both the establishment of primary tumors as well as to the initiation, establishment, and growth of metastases. However, there may be different requirements for the primary tumor compared with the distant environment. In many ways, the tumor microenvironment resembles the microenvironments used in development and tissue repair. The tumor-associated stromal cells (e.g., macrophages and fibroblasts) are different from their counterparts in the normal tissue.58 They may be newly recruited from the bone marrow and have more embryonic character, but they are also misregulated. Altering the tumor microenvironment therapeutically has promise for improving the cancer therapy on a wide-spread basis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA057621, R01 CA138818, U01 ES019458).

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Egeblad M, Ewald AJ, Askautrud HA, et al. Visualizing stromal cell dynamics in different tumor microenvironments by spinning disk confocal microscopy. Dis Model Mech. 2008;1:155–167. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egeblad M, Nakasone ES, Werb Z. Tumors as organs: complex tissues that interface with the entire organism. Dev Cell. 2010;18:884–901. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin EY, Gouon-Evans V, Nguyen AV, et al. The macrophage growth factor CSF-1 in mammary gland development and tumor progression. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2002;7:147–162. doi: 10.1023/a:1020399802795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Campbell JM, et al. Collagen reorganization at the tumor-stromal interface facilitates local invasion. BMC Med. 2006;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:395–406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schor SL, Ellis IR, Jones SJ, et al. Migration-stimulating factor: a genetically truncated onco-fetal fibronectin isoform expressed by carcinoma and tumor-associated stromal cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8827–8836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaggioli C, Hooper S, Hidalgo-Carcedo C, et al. Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1392–1400. doi: 10.1038/ncb1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pietras K, Pahler J, Bergers G, et al. Functions of paracrine PDGF signaling in the proangiogenic tumor stroma revealed by pharmacological targeting. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuperwasser C, Chavarria T, Wu M, et al. Reconstruction of functionally normal and malignant human breast tissues in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4966–4971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401064101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen-Ngoc KV, Cheung KJ, Brenot A, et al. ECM microenvironment regulates collective migration and local dissemination in normal and malignant mammary epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2595–E2604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212834109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avraamides CJ, Garmy-Susini B, Varner JA. Integrins in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:604–617. doi: 10.1038/nrc2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erler JT, Weaver VM. Three-dimensional context regulation of metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26:35–49. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9209-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giannelli G, Falk-Marzillier J, Schiraldi O, et al. Induction of cell migration by matrix metalloprotease-2 cleavage of laminin-5. Science. 1997;277:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montgomery AM, Reisfeld RA, Cheresh DA. Integrin alpha v beta 3 rescues melanoma cells from apoptosis in three-dimensional dermal collagen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8856–8860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeNardo DG, Barreto JB, Andreu P, et al. CD4(+) T cells regulate pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeNardo DG, Brennan DJ, Rexhepaj E, et al. Leukocyte complexity predicts breast cancer survival and functionally regulates response to chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:54–67. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lohela M, Casbon AJ, Olow A, et al. Intravital imaging reveals distinct responses of depleting dynamic tumor-associated macrophage and dendritic cell subpopulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E5086–E5095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419899111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casbon AJ, Reynaud D, Park C, et al. Invasive breast cancer reprograms early myeloid differentiation in the bone marrow to generate immunosuppressive neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E566–E575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424927112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagerling C, Casbon AJ, Werb Z. Balancing the innate immune system in tumor development. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:24–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey SR, Nelson MH, Himes RA, et al. TH17 cells in cancer: the ultimate identity crisis. Front Immunol. 2014;5:276. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mantovani A, Romero P, Palucka AK, et al. Tumour immunity: effector response to tumour and role of the microenvironment. Lancet. 2008;371:771–783. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60241-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1073–1081. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta:“N1” versus“N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:253–268. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, et al. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coussens LM, Raymond WW, Bergers G, et al. Inflammatory mast cells up-regulate angiogenesis during squamous epithelial carcinogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1382–1397. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang FC, Ingram DA, Chen S, et al. Nf1-dependent tumors require a microenvironment containing Nf1+/−- and c-kit–dependent bone marrow. Cell. 2008;135:437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, et al. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivera LB, Bergers G. Intertwined regulation of angiogenesis and immunity by myeloid cells. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rivera LB, Meyronet D, Hervieu V, et al. Intratumoral myeloid cells regulate responsiveness and resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. Cell rep. 2015;11:577–591. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwasaki H, Suda T. Cancer stem cells and their niche. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1166–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller SJ, Lavker RM, Sun TT. Interpreting epithelial cancer biology in the context of stem cells: tumor properties and therapeutic implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1756:25–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Howe JR, Roth S, Ringold JC, et al. Mutations in the SMAD4/DPC4 gene in juvenile polyposis. Science. 1998;280:1086–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirkland SC. Type I collagen inhibits differentiation and promotes a stem cell-like phenotype in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:320–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheung KJ, Gabrielson E, Werb Z, et al. Collective invasion in breast cancer requires a conserved basal epithelial program. Cell. 2013;155:1639–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, et al. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weaver VM, Petersen OW, Wang F, et al. Reversion of the malignant phenotype of human breast cells in three-dimensional culture and in vivo by integrin blocking antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:231–245. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massagué J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:274–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peinado H, Alečković M, Lavotshkin S, et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med. 2012;18:883–891. doi: 10.1038/nm.2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. Drug penetration in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:583–592. doi: 10.1038/nrc1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sounni NE, Dehne K, van Kempen L, et al. Stromal regulation of vessel stability by MMP14 and TGFbeta. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:317–332. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakasone ES, Askautrud HA, Kees T, et al. Imaging tumor-stroma interactions during chemotherapy reveals contributions of the microenvironment to resistance. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:488–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loeffler M, Krüger JA, Niethammer AG, et al. Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts improves cancer chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1955–1962. doi: 10.1172/JCI26532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Polyak K, Haviv I, Campbell IG. Co-evolution of tumor cells and their microenvironment. Trends Genet. 2009;25:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]