Abstract

Threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) is a modified nucleoside universally conserved in tRNAs in all three kingdoms of life. The recently discovered genes for t6A synthesis, including tsaC and tsaD, are essential in model prokaryotes but not essential in yeast. These genes had been identified as antibacterial targets even before their functions were known. However, the molecular basis for this prokaryotic-specific essentiality has remained a mystery. Here, we show that t6A is a strong positive determinant for aminoacylation of tRNA by bacterial-type but not by eukaryotic-type isoleucyl-tRNA synthetases and might also be a determinant for the essential enzyme tRNAIle-lysidine synthetase. We confirm that t6A is essential in Escherichia coli and a survey of genome-wide essentiality studies shows that genes for t6A synthesis are essential in most prokaryotes. This essentiality phenotype is not universal in Bacteria as t6A is dispensable in Deinococcus radiodurans, Thermus thermophilus, Synechocystis PCC6803 and Streptococcus mutans. Proteomic analysis of t6A- D. radiodurans strains revealed an induction of the proteotoxic stress response and identified genes whose translation is most affected by the absence of t6A in tRNAs. Thus, although t6A is universally conserved in tRNAs, its role in translation might vary greatly between organisms.

Keywords: tRNA, maturation, translation, modified nucleosides, t6A

Introduction

Complex tRNA modifications, often requiring multiple enzymes for their synthesis, are found in the anticodon loop at positions 34 or 37 of many tRNAs, and these modifications are critical for accurate decoding of mRNA codons (Agris et al., 2007, El Yacoubi et al., 2012). Threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A37) is one of the few universal complex modifications in the anticodon loop at position 37 (Jühling et al., 2009). It is found in virtually all tRNAs decoding ANN codons, and its biosynthetic pathway was recently elucidated (Deutsch et al., 2012), revealing major differences between the three domains of life (Thiaville et al., 2014b).

Two core enzyme families are required for t6A synthesis in all domains of life (Figure 1) (El Yacoubi et al., 2011 El Yacoubi et al., 2009, Wan et al., 2013, Thiaville et al., 2014a). The first is TsaC (Tcs1 in Archaea and Eukarya) or its ortholog Sua5 [TsaC2 in Bacteria or Tcs2 in Archaea and Eukarya; see (Thiaville et al., 2014b) for new gene nomenclature of t6A synthetic genes]; TsaC2 differs from TsaC by an additional C-terminal Rossman fold domain. The second is TsaD or its orthologs Kae1 (Tcs3), part of the KEOPS (Kinase Endopeptidase and Other Proteins of Small size) complex (renamed TCTC – threonylcarbamoyl transferase complex), or Qri7 (Tcs4) found in the mitochondria (Wan et al., 2013, Thiaville et al., 2014a). In addition, bacteria generally require TsaB and TsaE enzymes to synthesize t6A (Deutsch et al., 2012, Lauhon, 2012), whereas archaea and eukaryotes require the other subunits of the KEOPS (TCTC) complex [Cgi121 (Tcs7), Pcc1 (Tcs6), Bud32 (Tcs5) and the yeast specific Gon7 (Tcs8) (Daugeron et al., 2011, Perrochia et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2015)].

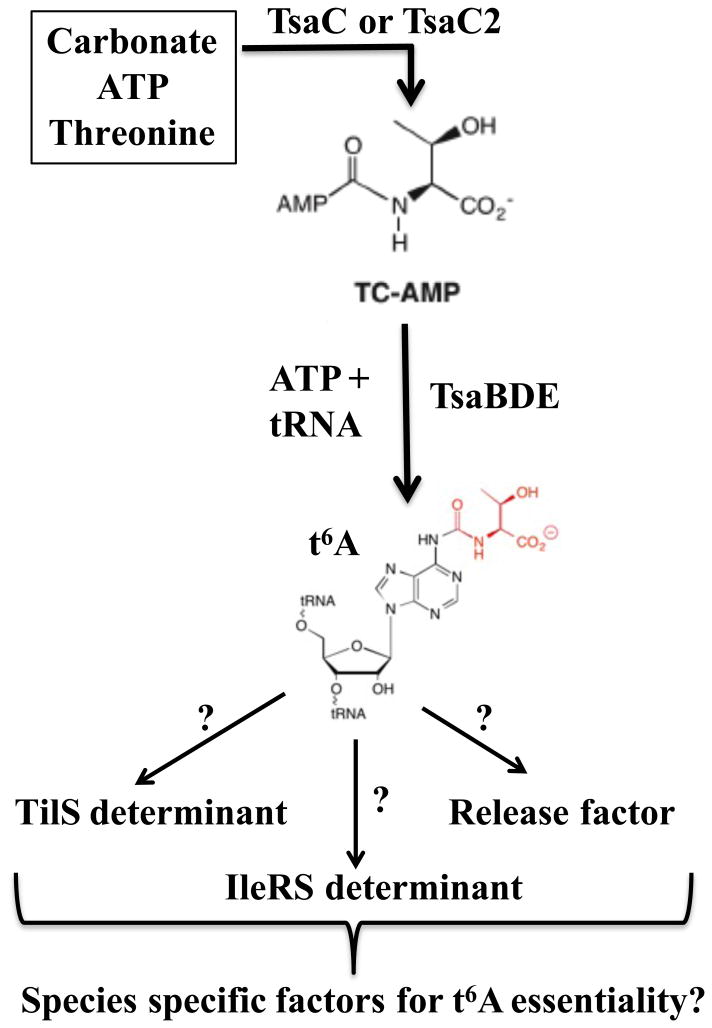

Figure 1.

Pathway for biosynthesis of t6A37 and its possible roles in tRNA function. TC-AMP, threonine-carbamoyl-AMP.

Another major difference between kingdoms in t6A biosynthetic enzymes is the essentiality of the corresponding genes. None of the t6A synthesis genes are essential in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, although deletion of SUA5 or KAE1 leads to severe growth phenotypes (Na et al., 1992, Kisseleva-Romanova et al., 2006). t6A synthesis genes could also be deleted in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Kim et al., 2010, Spirek et al., 2010), and T-DNA insertions have been isolated in most t6A synthesis genes in Arabidopsis thaliana (Alonso et al., 2003) (Table 1), however, follow up studies are required to rigorously assess their dispensability. Although t6A synthesis genes are dispensable in eukaryotes, this is not the case in most prokaryotes. Indeed, all t6A synthesis genes are essential in the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis (Sarmiento et al., 2013). In the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii, only pcc1 could be deleted, reducing the t6A content of tRNAs only slightly (Naor et al., 2012) (Table 1). The four tsaBCDE genes are individually essential in Escherichia coli and many other gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (Table 2). Because of their prokaryotic-specific essentiality, these genes had been identified as potential antibacterial targets even before their role in t6A synthesis was established, and inhibitors of TsaE were developed based on its ATP binding capabilities (Arigoni et al., 1998, Freiberg et al., 2001, Allali-Hassani et al., 2004, Lerner et al., 2007, Handford et al., 2009). However, for t6A synthesis proteins to be considered viable targets for antibiotics, it is critical to understand their distribution profile as well as the reasons underlying their essentiality in bacteria.

Table 1. Essentiality of t6A synthesis genes in eukaryotes and archaea.

New nomenclatures for t6A biosynthetic genes are listed in parenthesis. All genes are essential except those highlighted in grey. Essentiality of gene names underlined has not been determined.

| Organism | TsaC (Tcs1) |

Sua5 (Tcs2) |

Kae1 (Tcs3) |

Qri7 (Tcs4) |

Bud32 (Tcs5) |

Pcc1 (Tcs6) |

Cgi121 (Tcs7) |

Gon7 (Tcs8) |

Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haloferax volcanii DS2 | HVO_0253 | HVO_18951 | HVO_18951 | HVO_0652 | HVO_0013 | Single gene knockout | (Blaby et al., 2010, Naor et al., 2012) | |||

| Methanococcus maripaludis | MMP0186 | MMP0415# | MMP0415# | MMP0246 | MMP0967 | (Sarmiento et al.) | ||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae S228C | YGL169w | YKR038c | YDL104c | YGR262c | YKR095w-A | YML036w | YJL184w | Single gene knockout in haploid | (Winzeler, 1999, El Yacoubi et al., 2009) | |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | SPCC895.03cc | SPBC16D10.03 | SPCC1259.10 | SPAP27G11.07c | SPAC4H3.13 | SPCC24B10.12 | SPAC6B12.18 | Single gene knockout | (Kim et al., 2010, Spirek et al., 2010) | |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AT5G60590 | AT4G22720 | AT2G45270 | AT5G26110 | AT5G53045 | AT4G34412 | tDNA mutagenesis | (Alonso et al., 2003) |

N.P. = gene not present in genome.

H. volcanii kae1 and bud32 occur as a gene fusion (HVO_1895)

Table 2. Essentiality phenotypes of t6A synthesis genes in bacteria.

All genes are essential except those highlighted in grey. Essentiality of gene names underlined has not been determined.

| Organism | TsaC | Sua5 (TsaC2) | TsaB | TsaD | TsaE | Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli K12 | b3282 | b1807 | b3064 | b4168 | Whole Genome, single gene knockout, non-polar | (Baba et al., 2006, Kitagawa et al., 2006) | |

| Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor E7946 and C6706 | VC0054 | VC1079 | VC1989 | VC0521 | VC0343 | Saturating transposon mutagenesis | (Chao et al., 2013, Kamp et al., 2013) |

| Caulobacter crescentus NA1000 | CCNA_03501 | CCNA_00057 | CCNA_00069 | CCNA_03648 | Saturating transposon mutagenesis | (Christen et al., 2011) | |

| Mycoplasm genitaliumG37 | MG259* | MG208 | MG046 | N.P. | Saturating transposon mutagenesis | (Glass et al., 2006) | |

| Mycoplasm pulmonis | MYPU_6130# | MYPU_1190 | MYPU_1180 | MYPU_1200 | Saturating transposon mutagenesis | (French et al., 2008, Dybvig et al., 2010) | |

| Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. 168 | BSU36950 | BSU05920 | BSU05940 | BSU05910 | Whole Genome, single gene knockout, non-polar | (Kobayashi et al., 2003) | |

| Haemophilus influenzae Rd | HI0656 | HI0388 | HI05301 | HI0065 | mariner-based minitransposon | (Akerley et al., 2002) | |

| Acinetobacter baylyi APD1 | ACIAD0208 | ACIAD06772 | ACIAD13322 | ACIAD2376 | Whole Genome, single gene knockout3 | (de Berardinis et al., 2008) | |

| Salmonella Typhii TY2 | STY4395 | STY1950 | STY3387 | STY4714 | Saturating transposon mutagenesis | (Langridge et al., 2009) | |

| Francisella novicida U112 | FTN_0158 | FTN_1148 | FTN_1565 | FTN_0274 | Saturating transposon mutagenesis | (Gallagher et al., 2007) | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 | PA0022 | PA3685 | PA0580 | PA4948 | Saturating transposon mutagenesis | (Jacobs et al., 2003) | |

| Burkholderia thailandensis E264 | BTH_I0669 | BTH_I2001 | BTH_II0616 | BTH_I0723 | Saturating transposon mutagenesis | (Gallagher et al., 2013) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus MW2 | MW0860 | MW2040 | MW1975 | MW1973 | MW1976 | Saturating transposon mutagenesis | (Chaudhuri et al., 2009) |

| Deinococcus radiodurans R1 | DR_1862 | DR_0756 | DR_0382 | DR_2351 | Single gene knockout | (Onodera et al., 2013) | |

| Synechocystis sp. PCC 6308 | slr1866 | sll1063 | slr0807 | sll0257 | Single gene knockout | (Zuther et al., 1998) | |

| Streptococcus mutans UA159 | SMU.1083c | SMU.385 | SMU.387 | SMU.409 | Single gene knockout | (Bitoun et al., 2014) |

N.P. = Gene not present in genome.

M. genitalium MG259 is a TsaC/HemK fusion.

M. pulmonis TsaC (MYPU_6130) is essential, while HemK (MYPU_1060) is not essential. (Dybvig et al., 2010)

Genomic map for TsaD (HI0530) mutation is not available and mutation is not confirmed.

Mutations correspond with genomic duplication of the target gene.

Library was selected on minimal media.

In terms of phylogenetic distribution, 90% of the bacteria sequenced to date contain homologs of the four t6A synthesis proteins (Thiaville et al., 2014b). A subset (2.2%) lack TsaB (Thiaville et al., 2014b) and a few lack both TsaB and TsaE (Grosjean et al., 2014). These latter organisms, which include pathogenic bacteria such as Mycoplasma haemofelis and Mycoplasma suis strain Illinois, would, therefore, not be sensitive to inhibitors targeting TsaB. Saturating mutagenesis or whole genome single gene deletion studies showed that t6A synthesis genes were essential in 11 out of 13 cases, with the possible exceptions being two reports on Vibrio cholerae (Table 2). Interestingly, the V. cholerae genomes contain both the tsaC and sua5 (tsaC2) forms, and either gene alone is sufficient for growth (Chao et al., 2013, Kamp et al., 2013). Finally, t6A synthesis genes can be deleted in some bacteria, for example, tsaD and tsaB in Deinococcus radiodurans (Onodera et al., 2013); tsaD in Synechocystis PCC 6803 (Zuther et al., 1998); and, tsaE in Streptococcus mutans (Bitoun et al., 2014). Some discrepancies were found in Bacillus subtilis, where all four t6A genes were found to be essential in a global transposon study (Table 2), but two of them, ywlC (sua5 homolog) and ydiB (tsaE homolog) were found to be dispensable in follow-up targeted studies (Hunt et al., 2006). Yet again, because these studies were performed before the t6A biosynthetic pathway had been fully elucidated, it is not known if t6A is actually absent in these mutants, or whether other routes for t6A synthesis exist in these specific organisms.

Comparison of the translation machineries in the different kingdoms could explain the essentiality of t6A synthesis enzymes in bacteria and archaea but not eukaryotes. t6A has been proposed to be a determinant for charging of tRNAIleGAU by isoleucyl tRNA synthetase (IleRS) in E. coli (Nureki et al., 1994, Giegé & Lapointe, 2009), while it is not a major determinant for the yeast IleRS, which requires Inosine 34 for the major tRNAIleAAU and Ψ34 (and perhaps Ψ36) for the minor tRNAIleUAU (even though t6A might contribute somewhat to the charging efficiency) (Senger et al., 1997, Giegé & Lapointe, 2009). While a difference in the role of t6A as a determinant for the bacterial-type but not the eukaryotic-type IleRSs could explain its essentiality in Bacteria and not in yeast, it would not account for the essentiality of t6A in Archaea, which harbor eukaryotic-type IleRS enzymes (Ibba et al., 1999).

Another potential basis for the prokaryotic specific essentiality of t6A is if it is a determinant for tRNAIle lysidine synthase (TilS) and agmatidine synthase (TiaS). In most prokaryotes, but not eukaryotes, the codon AUA is decoded by a tRNAIle bearing a CAU anticodon in which C is modified to lysidine (k2C) by TilS in Bacteria or to agmatidine (agm2C) by TiaS in Archaea (Soma et al., 2003, Ikeuchi et al., 2010, Mandal et al., 2010). Since the corresponding genes, tilS and tiaS, are essential (Soma et al., 2003, Blaby et al., 2010), the essentiality of t6A in prokaryotes could be due to an indirect role in k2C and agm2C synthesis. However, published biochemical studies seem to rule out such a role as unmodified transcripts of tRNAIleCAU are efficiently recognized by the TilS and TiaS enzymes (Ikeuchi et al., 2005, Ikeuchi et al., 2010, Osawa et al., 2011, Köhrer et al., 2008). Finally, since a tsaC mutant can act as a suppressor of prfA1 encoding a thermosensitive (ts) Release Factor 1 (RF1) in E. coli (Kaczanowska & Ryden-Aulin, 2004, Kaczanowska & Rydén-Aulin, 2005), and the absence of t6A in tRNAs is known to increase read-through of termination codons in yeast (Lin et al., 2009), the essentiality of t6A in bacteria could also be due to an unforeseen interplay with translation termination (Dreyfus & Heurgue-Hamard, 2011).

In E. coli, it has been reported that the growth phenotype caused by the depletion of TsaB, TsaD or TsaE was partially suppressed by overexpression of rstA, part of a two-component-system response regulator (Handford et al., 2009, Campbell et al., 2007). This suggested that these genes belonged to a complex regulatory network (Msadek, 2009), but the rstA suppression phenotype has never been really explained. Overexpression of other genes such as rho, encoding a transcription terminator, or dnaG, encoding DNA primase, have also been reported to suppress the essentiality phenotype caused by depletion of the t6A synthesis enzymes (Bergmiller et al., 2012, Hashimoto et al., 2011, Hashimoto et al., 2013), but it is unknown if t6A is absent from tRNA isolated from these suppressor strains. Lack of t6A-modificed tRNA in these strains would compromise the development of antibacterials targeting the enzymes of t6A machinery, as resistant clones could be selected at a high frequency.

Finally, phenotypes deriving from the absence or reduction of t6A enzymes in prokaryotes are very diverse, and include defects in cell division or in stress responses, increased glycation of proteins, or cyanophycin accumulation (Handford et al., 2009, Allali-Hassani et al., 2004, Bitoun et al., 2014, Zuther et al., 1998, Oberto et al., 2009, Katz et al., 2010, Bergmiller et al., 2011). However, the molecular basis for these pleiotropic phenotypes has not been established, and it is unknown whether these phenotypes are all due to translation defects caused by the absence of the modification, whether t6A has roles in the cell not linked to translation, or whether the genes for t6A biosynthesis have roles in the cell unrelated to t6A synthesis.

In view of these uncertainties and conflicting reports, and the importance of t6A enzymes in the bacteria analyzed to date, t6A levels were measured in different derivatives of E. coli reported to have circumvented the essentiality of t6A synthesis enzymes and in t6A gene deletion mutants of Synechocystis, D. radiodurans and S. mutans. This analysis revealed that t6A is strictly essential in E. coli but not in all bacteria. Through a combination of biochemical, genetic and proteomic experiments, we set out to understand these differences in t6A function along the bacterial phylogenetic tree.

Results

t6A is present in E. coli derivatives reported to have suppressed the essentiality of t6A genes

As discussed above, conditions in which E. coli survives in the absence of t6A synthesis enzymes have been reported. However, since most of these reports were published before the role of the tsaBCDE genes in t6A synthesis was established, we set out to measure t6A levels in these E. coli derivatives.

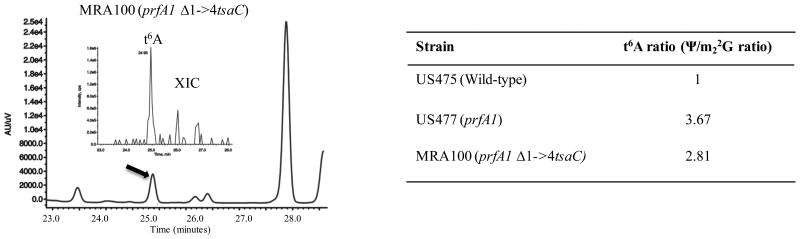

Deletion of the first four amino acids of TsaC was shown to suppress the growth defects of a prfA1 strain at non-permissive temperature (prfA1 encodes a thermosensitive RF1) (Kaczanowska & Ryden-Aulin, 2004). The two mutations Δ1->4tsaC and prfA1 could not be separated, and the presence of the Δ1->4tsaC allele led to defects in ribosome maturation, hence the name rimN (Kaczanowska & Rydén-Aulin, 2005). In order to assess if this suppression was accompanied by a change in t6A levels, we compared t6A levels in the single mutant prfA1 (US477), the double mutant Δ1->4tsaC prfA1 (MRA100), and the isogenic wild-type E. coli strain (US475). As shown in Figure 2, cells carrying the prfA1 allele or both Δ1->4tsaC, prfA1 alleles contained t6A in tRNAs. In fact, in two independent experiments it was found that both strains contained a higher level of t6A (∼2-3 times more) than the parental strain. Eliminating the first four amino acids of TsaC clearly does not lower t6A levels in tRNAs and, therefore, suppression of the prfA1 thermosensitive phenotype is not due to a global loss or reduction of t6A modification in tRNAs.

Figure 2.

Evidence for presence of t6A in tRNAs isolated from E. coli carrying the prfA1 allele (US477) or both prfA1 Δ1->4tsaC alleles (MRA100) based on LC-MS/MS analysis. (left) Analysis of t6A levels in MRA100. Black arrow indicates t6A peak; inset shows extracted ion chromatogram (XIC) corresponding to the molecular ion for t6A. (right) Comparison of relative t6A levels in wild-type and mutant strains. The ratio of Ψ-modified base/m22G were used to normalize the level tRNAs between strains.

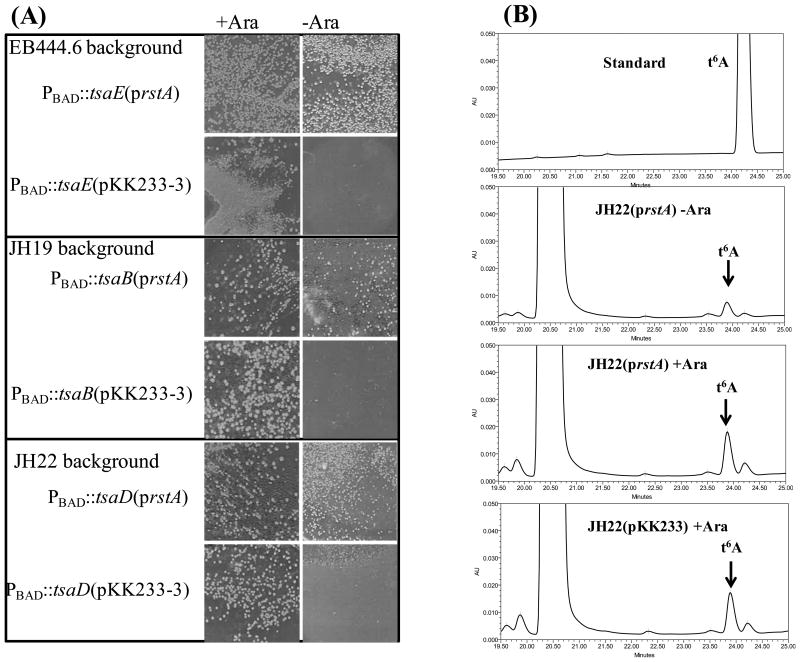

Overexpression of the response regulator rstA has been reported to partially suppress the essentiality phenotype of TsaB, TsaD, or TsaE depletion (Campbell et al., 2007, Handford et al., 2009). First, we sought to duplicate these results using the strains from the above-mentioned studies. In these strains, the chromosomal copies of the tsaB, tsaD, or tsaE genes, respectively, have been placed under the control of the arabinose-inducible PBAD promoter and hence the cells do not grow in the absence of arabinose. Transforming these strains with prstA that expresses the rstA gene under the control of an IPTG inducible promoter allowed growth of the three strains on LB agar in the absence of the arabinose inducer (Figure 3A). This suppression was not observed with the parent control vector pKK223-3 (Campbell et al., 2007). t6A levels were then analyzed from tRNAs of tsaD- PBAD∷tsaD (prstA) (VDC9607) cells grown in absence of arabinose under conditions where the control tsaD- PBAD∷tsaD (pKK223-3) (VDC9606) strain did not grow (data not shown). As shown in Figure 3B, tRNAs extracted from tsaD- PBAD∷tsaD (prstA) grown in absence of arabinose contain t6A, even if levels under non-induced conditions are lower (33% less).

Figure 3.

Overexpression of rstA does not suppress the essentiality of t6A in E. coli. (A) The chromosomal copies of tsaE (EB444.6), tsaB (JH19), or tsaD (JH22) have been placed under control of the arabinose-inducible PBAD promoter. Each strain was transformed with an equal amount of plasmid prstA and plated with or without the inducer arabinose; pKK233-3, empty plasmid. (B) Analysis of t6A content in tRNA isolated from various strain JH22 derivatives. Strains were grown static, overnight at 37 °C in LB-amp with 0.05% of the inducer arabinose. The following day, each culture was diluted 1:100 in LB-amp containing either 0.2% arabinose or 0.2% glucose. The cultures were grown at 37 °C with shaking for 4 hours, then the arabinose grown cultures were diluted 1:100 into LB-amp with 0.2% arabinose and the glucose-grown cultures were diluted into LB-amp with 0.2% glucose. The cultures were grown at 37 °C with shaking until the OD600nm reached approximately 1.5. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and bulk tRNA was extracted and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods.

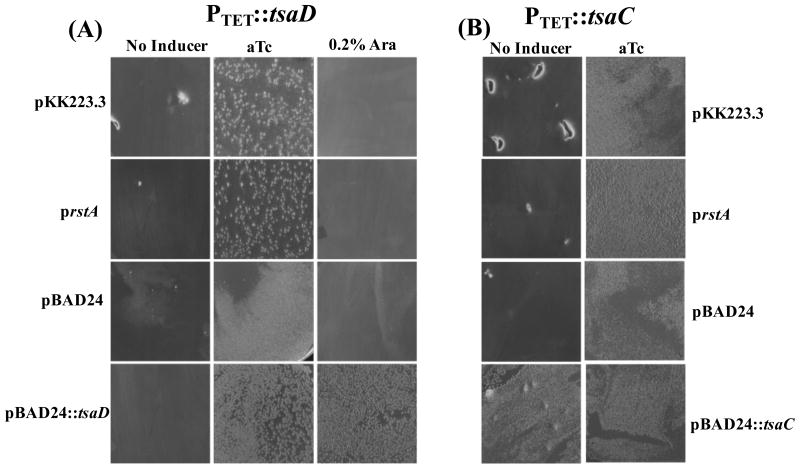

These results suggested that the known leakiness of the PBAD promoter in the absence of the inducer arabinose (Campbell et al., 2007) is sufficient to sustain cells with enough of the TsaD enzyme to assure t6A synthesis and growth. Therefore, a PTET promoter, which is known to be more tightly controlled, was used for subsequent studies. prstA was used to transform a PTET∷tsaD strain where the native tsaD promoter was replaced by the anhydrotetracycline (aTc) inducible PTET promoter (VDC5801) (El Yacoubi et al., 2011). In this genetic set up, over-expression of rstA in PTET∷tsaD did not allow growth in the absence of the inducer (aTc) (Figure 4A). A similar result was observed in PTET∷tsaC strain (VDC5684) where the tsaC gene encoding the first enzyme of the t6A pathway is under PTET control (Gerdes et al.) (Figure 4B). The PBAD∷tsaC plasmid can complement growth of the PTET∷tsaC strain in the absence of any inducer [(as previously shown (Gerdes et al.)], confirming that low TsaC levels allow growth of E. coli (Figure 4B). Our results therefore suggest that high expression of rstA allows cells to grow with low levels of t6A (PBAD backgrounds) but not with zero t6A (PTET backgrounds).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of rstA does not compensate for the absence of tsaD or tsaC. The chromosomal copies of tsaD (PTET∷tsaD) (A) or tsaC (PTET∷tsaC) (B) have been placed under control of the tightly regulated PTET promoter. For complementation assays, cells were transformed with 100 ng of plasmid (prstA, pBAD24 or pBAD∷tsaD) via electroporation, then recovered with 1 mL of LB and placed at 37°C for 1 hour with shaking. 200 μL of cells were plated on LB-amp supplemented with or without aTc (50 ng/ml) or 0.02% arabinose.

In summary, our results suggest that to date the essentiality of t6A has never been suppressed in E. coli K12. These results, in combination with the observation that all four t6A synthesis genes are individually essential in E. coli K12 (Table 2), strongly support the essential nature of this universal modification in this model organism.

The essentiality of the t6A modification of tRNA in E. coli is not strain dependent

Since many of the suppression studies described above had been performed in different E. coli K12 strains, we therefore explored if the essentiality phenotype was dependent on the strain background. The PTET∷tsaD and PTET∷tsaC alleles from BW25113 were transferred by P1 transduction into E. coli B and E. coli C600 [VDC7061/62, VDC7065/66, VDC7069/70 and VDC7073/74, respectively]. The transduced alleles were checked by PCR (Figure S1), and tested for β-galactosidase activity (donors are LacZ- and both recipients are LacZ+) and for growth in the absence of aTc. In the C600 background, PTET∷tsaC and PTET∷tsaD transductants required aTc for growth, like in the BW25113 donor derivatives (Table 3). However, the E. coli B transductants of both PTET∷tsaC and PTET∷tsaD grew in the absence of aTc (Table 3). To test if this growth was due to mutations rendering the PTET promoter constitutive, these strains were used as donors for P1 transduction back into BW25113. Growth of four BW25113 PTET∷tsaC back transductants remained aTc independent (Figure S2), suggesting that mutations in the PTET promoter made it constitutive, or that suppressor mutations that allow growth in the absence of t6A and are co-transduced with the PTET∷tsaC allele are present in the E. coli B PTET∷tsaC derivatives. Analysis of bulk tRNA extracted from E. coli B PTET∷tsaC (VDC7066) grown in LB without aTc inducer shows wild-type levels of t6A (Figure S1), suggesting mutations making PTET constitutive had occurred. Whole genome sequencing of VDC7066, as detailed in the Supplemental Results Section, revealed that the tetR allele contains a T1173G change, creating a non-synonymous Q38P mutation. This mutation is located in the TetR DNA binding site (Ramos et al., 2005) and most likely makes the expression of PTET promoter constitutive. On the other hand, growth of four back-transductants of BW25113 PTET∷tsaD were dependent on aTc, unlike the E. coli B PTET∷tsaD donor (VDC7062) (Figure S2), hence the PTET promoter was still regulated. This left three possible explanations: 1) tsaD, and therefore t6A in tRNA, is not essential in the E. coli B background; 2) a suppressor mutation that allows expression of the PTET∷tsaD allele in the absence of aTc is present in the E. coli B donor but did not transduce with the PTET∷tsaD allele; 3) a suppressor mutations makes tsaD dispensable for t6A synthesis. Here too, the presence of wild-type levels of t6A in bulk tRNA extracted from VDC7062 grown without inducer suggested the first explanation explanation is not correct (Figure S1). The whole genome sequence of VDC7062 was determined as reported in the Supplemental Results Section but this did not provide any obvious explanation as to why VDC7062 does not require aTc for growth, so we could not discriminate between that last two hypotheses.

Table 3. Growth phenotypes of strains carrying conditional tsaC and tsaD alleles.

| Strain | Lac | Growth –aTc | Growth +aTc | Kan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C600 | + | + | + | S |

| E. coli B | + | + | + | S |

| VDC5684 BW25113 PTET∷tsaC∷aph | - | + | + | R |

| VDC5801 BW25113 PTET∷tsaD∷aph | - | - | + | R |

| VDC7073 C600 PTET∷tsaC∷aph | + | - | + | R |

| VDC7069 C600 PTET∷tsaD∷aph | + | - | + | R |

| VDC7065 E. coli B PTET∷tsaC∷aph | + | + | + | R |

| VDC7061 E. coli B PTET∷tsaD∷aph | + | + | + | R |

Our results show that t6A genes are essential in a least two, and maybe three different E. coli backgrounds, and show that the genetic set-ups that limit the expression of t6A synthesis genes are unstable under high selective pressure to express these essential genes.

t6A is a positive determinant for E. coli IleRS

The identity elements for the 20 aminoacylation systems of E. coli have been analyzed, and the isoleucine system was the only one proposed to be dependent on t6A for identity determination [for review see (Giegé et al., 1998)]. The recent discovery of the t6A machinery and the ability to modify transcripts in vitro now allow addressing this experimentally.

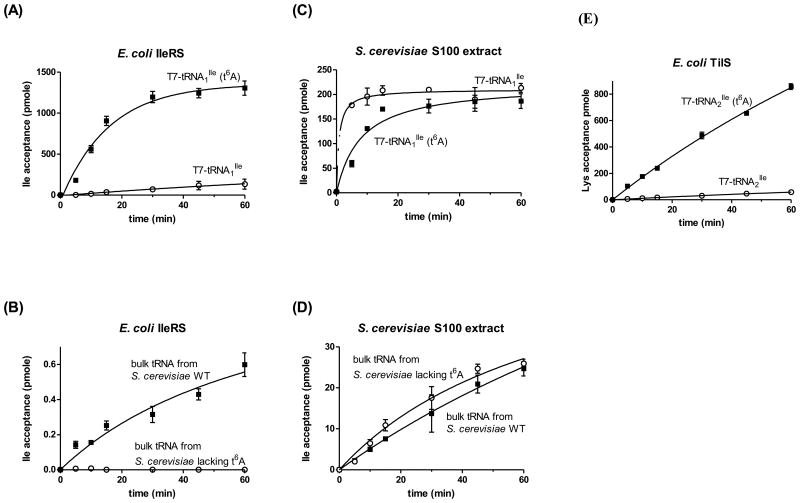

To test whether t6A at position 37 is required for E. coli IleRS to charge the major E. coli isoleucine tRNA (tRNAIleGAU), the corresponding T7 transcript was generated with and without t6A at position 37. As shown in Figure 5A, under the specific conditions used in here and at early time points, in vitro aminoacylation of the t6A-containing tRNAIleGAU transcript using E. coli IleRS has a significantly faster aminoacylation rate (at least 25-fold higher) than that of unmodified tRNAIleGAU transcript. Basically a similar result was obtained with bulk tRNA from S. cerevisiae wild-type and bulk tRNA from a yeast mutant specifically lacking t6A (Figure 5B), supporting the hypothesis that t6A at position 37 acts as a strong positive determinant for E. coli IleRS. In contrast, S. cerevisiae IleRS present in a total S100 extract aminoacylates bulk tRNA from yeast with similar rates irrespective of the t6A modification state and shows only a moderate preference for unmodified over modified E. coli tRNAIleGAU transcript (Figure 5C-D).

Figure 5.

In vitro aminoacylation or lysidinylation of tRNA containing or lacking t6A. (A) Aminoacylation of a transcript of E. coli tRNAIleGAU containing only t6A or no t6A using E. coli IleRS. (B) Aminoacylation of bulk tRNA from S. cerevisiae BY4741 (wild-type) or VDC9100 (Δsua5, t6A-) using E. coli IleRS. (C) Aminoacylation of a transcript of E. coli tRNAIleGAU containing only t6A or no t6A using S. cerevisiae S100 extract. (D) Aminoacylation of bulk tRNA from S. cerevisiae BY4741 (wild-type) or VDC9100 (Δsua5, t6A-) using S. cerevisiae S100 extract. (E) Lysidinylation of a transcript of E. coli tRNAIleCAU containing only t6A or no t6A using E. coli TilS. The relative rates of isoleucine or lysine acceptance in (A) and (E) were estimated by linear regression over the first 15 minutes of the reaction; 2.5 pmole/min for T7-tRNAIleGAU and 62.0 pmole/min for T7-tRNAIleGAU (t6A) using E. coli IleRS, 1.2 pmole/min for T7-tRNAIleCAU and 15.8 pmole/min for T7-tRNAIleCAU (t6A) using E. coli TilS, resulting in ∼25-fold and ∼13-fold higher rates for the respective modified transcript compared to the unmodified transcript. The actual fold increase of aminoacylation rates of modified versus unmodified transcript by E. coli IleRS is likely higher than 25-fold, since the enzyme concentration used was semi-saturating, as indicated by the time course shown in (A).

t6A improves the efficiency of the E. coli TilS enzyme in vitro

In most bacteria, the anticodon of the minor isoleucine tRNA (tRNAIleCAU) is k2CAU, where k2C stands for lysidine. tRNAIleCAU is transcribed as a pre-tRNA with the anticodon CAU, which is subsequently modified by TilS to k2CAU (Muramatsu et al., 1988b, Muramatsu et al., 1988a). Lysidine at the wobble position is required for recognition of the tRNA by bacterial IleRS (instead of by MetRS) and for the faithful decoding of AUA codons. The C-terminal domain of TilS binds the anticodon of tRNAIleCAU, and mutation of A37 to G37 was shown to reduce the activity of TilS (Ikeuchi et al., 2005), suggesting that t6A might also be important for TilS activity.

A T7 transcript of E. coli tRNAIleCAU was generated and modified in vitro to harbor t6A at position 37. As shown in Figure 5E, the t6A-containing transcript is a better substrate (approx. 13-fold) for E. coli TilS compared to the unmodified transcript. Thus, although the t6A-mediated enhancement of TilS activity is not as pronounced as that of IleRS activity described above, t6A could also be a positive determinant for E. coli TilS in the context of an otherwise unmodified E. coli tRNAIleCAU transcript.

The t6A essentiality phenotype of E. coli cannot be suppressed

In a final attempt to dissect t6A essentiality genetically, a direct search for suppressors of t6A absence using the PTET∷tsaC strain (VDC5684) was performed. In this strain, tsaC is cotranscribed with the aroE gene (Serina et al., 2004), so any mutation that makes the PTET promoter constitutive would eliminate the auxotrophy for aromatic amino acids. Derivatives with suppressor mutations not affecting the promoter would remain auxotrophic for aromatic amino acids. In repeated attempts, we failed to isolate any auxotrophic suppressors; all the aTc independent mutants isolated grew in the absence of amino acids (data not shown).

The failure to identify true suppressors lacking t6A in tRNA in our laboratory and in others as discussed above, together with the requirement of t6A for both E. coli IleRS charging and TilS activity in vitro suggests that t6A may be required for at least two essential cellular processes in E. coli. To separate decoding of AUA by a lysidine-modified tRNA from charging by IleRS, we designed several genetic strategies to circumvent these two essentiality factors in order to attempt the generation of a viable t6A depleted strain. These strategies relied on: 1) the observation that eukaryotic-type IleRSs from yeast and other organisms are functional in E. coli (Racher et al., 1991, Sassanfar et al., 1996); 2) yeast IleRS (and possibly other bacterial IleRS of eukaryotic-type) do not require t6A as a determinant for efficient charging while E. coli IleRS does [(Giegé & Lapointe, 2009) and results above], and; 3) expressing Mycoplasma mobile tRNAIle3UAU∷IleRS pair under the PLAC promoter (pNB26´2) (Taniguchi et al., 2013, Bohlke & Budisa, 2014) can complement the E. coli ΔtilS lethality phenotype and allows growth in the absence of k2C. Consistent with findings observed so far, repeated attempts to circumvent t6A essentiality in E. coli by co-expression of t6A independent IleRS and k2C independent tRNAs failed (Supplemental Results).

These negative results strongly support the possibility that the causes for t6A essentiality in E. coli are multiple and not yet fully understood and led us to explore other bacterial model organisms.

t6A is not essential in all bacteria

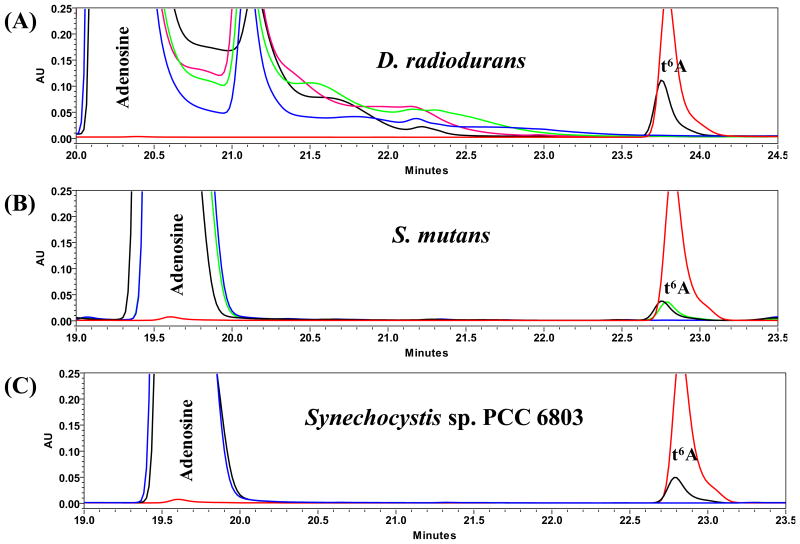

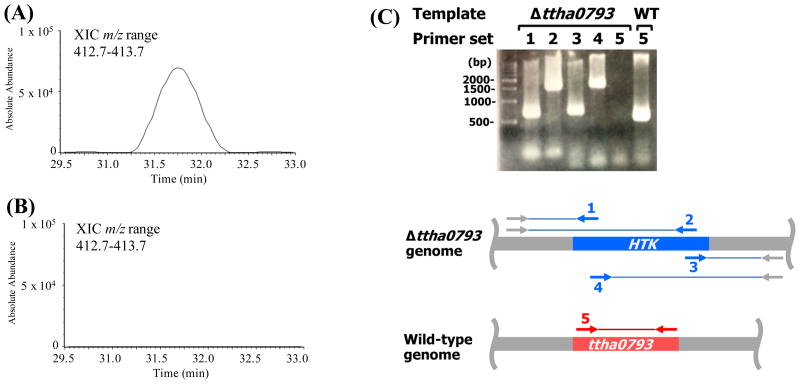

While, the results above confirmed that, at least for E. coli, t6A is strictly required for growth, derivatives harboring mutations in t6A genes have been reported for D. radiodurans R1, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6308 and S. mutans UA159 (Table 2). In order to test whether the deletion of t6A biosynthesis genes in these bacteria correlates with the loss of t6A in tRNAs, the levels of t6A were measured in D. radiodurans R1, ΔtsaD (XYD), ΔtsaB (XYZ) and ΔtsaDΔtsaB (WDZ); Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and ΔtsaD (gcp); as well as S. mutans UA159, ΔtsaE (JB409) and ΔtsaE(ptsaE) (JB409c) derivatives. In all cases, t6A was not detectable in tRNAs extracted from any of the mutant strains, while t6A was readily detected in tRNA extracted from the corresponding wild-type and complemented strains (Figure 6). Therefore, these bacteria are able to cope with the absence of t6A in tRNA (at least in laboratory conditions), while others, like E. coli, cannot (Table 2). We then set out to construct a tsaC null mutant in Thermus thermophilus HB8 under the assumption that, as this organism belongs to the Deinococcus-Thermus clade, it would be viable like D. radiodurans. As predicted, the ΔTttsaC strain was viable and tRNA analysis showed that this mutant also lacked detectable levels of t6A (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

HPLC analysis of nucleosides in digests of tRNAs extracted from wild-type and mutant strains of D. radiodurans, S. mutans and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Red line in each panel indicates t6A synthetic standard. (A) D. radiodurans R1: wild-type (black line), ΔtsaD,ΔtsaB (WDZ) (blue line), ΔtsaD (XYD) (green line), ΔtsaB (XYZ) (pink line). (B) S. mutans UA159: wild-type (black line), ΔtsaE (JB409) (blue line), ΔtsaE (ptsaE) (JB409c) (green line). (C) Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: wild-type (black line) and ΔtsaD (gcp) (blue line).

Figure 7.

t6A is absent in T. thermophilus ΔtsaC cells. Representative LC-MS nucleoside data of t6A obtained from total tRNA of T. thermophilus wild-type (A) and ΔtsaC (Δttha0793) mutant cells (B). Extracted ion chromatograms (XIC) for m/z range 412.7-413.7 corresponding to the molecular ion for t6A. (C) PCR verification of the deletion of tsaC (ttha0793) in T. thermophilus. The various primer sets (1-5) used for analysis of the relevant region in the Δttha0793 and wild-type genome are indicated below. HTK, kanamycin nucleotidyltransferase.

t6A is not a determinant for IleRS and TilS in all Bacteria

It is possible to partially rationalize the dispensability of t6A in D. radiodurans and T. thermophilus as these bacteria carry a eukaryotic-like and not a bacterial-like IleRS (Woese et al., 2000). However, both Synechocystis and S. mutans have bacterial-like IleRSs (Woese et al., 2000). To test the possibility that in the course of deleting the t6A synthesis genes suppressor mutations alleviating the requirement of t6A for IleRS charging occurred in these latter organisms, the S. mutans ΔtsaE mutant (SMU_409) and the parental S. mutans UA159 were sequenced. The parental strain contained 33 mutations when compared to the reference sequence (Dataset 1). These 33 variations were also present in ΔtsaE (SMU_409). Interestingly, one of these variations is a change of G to A at position 224 conferring a non-synonymous amino acid change of R75G in SMU_13 (TilS). This residue is not located in the tRNA binding region, hence further biochemical characterization studies are required to test if this mutation makes the S. mutans TilS t6A independent. In addition to these 33 variations, the ΔtsaE (SMU_409) strain contained a mutation conferring a K520N change in the ATP-dependent nuclease Rex A (SMU_1499). Given that this mutation is not obviously linked to a change in determinants for the S. mutans IleRS, we concluded that t6A is not a positive determinant for IleRS in S. mutans, and is the most parsimonious explanation for the growth seen in Synechocystis ΔtsaD.

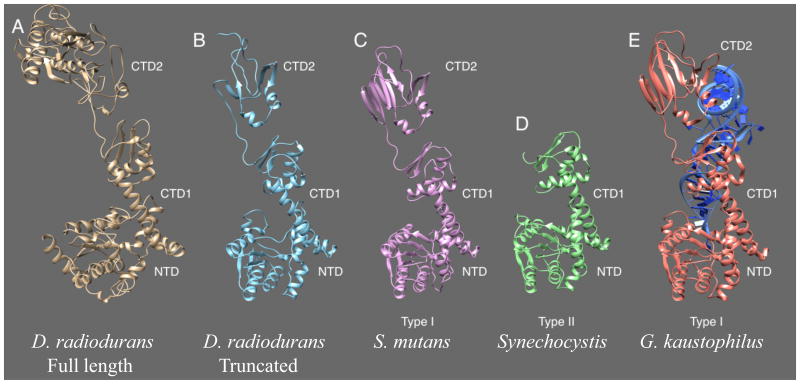

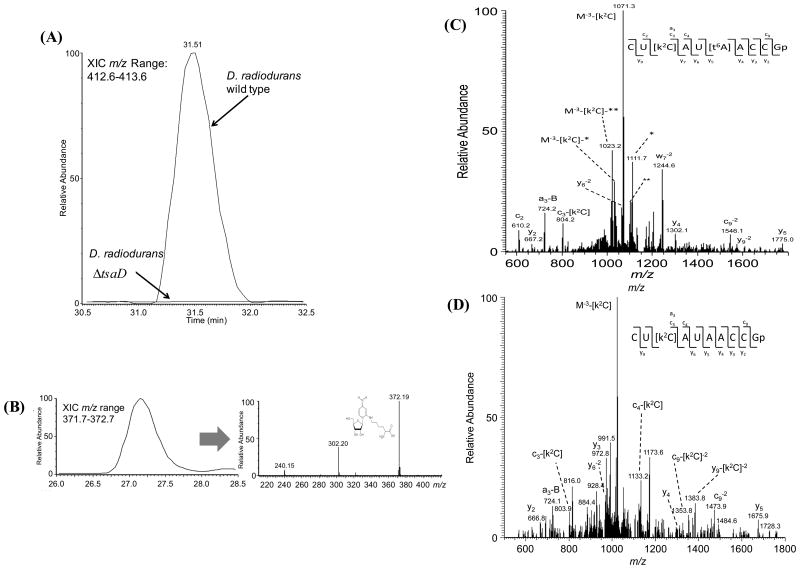

The D. radiodurans TilS protein, like its relative from the Deinococcus-Thermus phylum clade, is fused to a cytidine deaminase domain of unknown function that could affect its recognition of target tRNA (Figure 8). To address the question of whether t6A is a positive determinant for the TilS enzyme in D. radiodurans and T. thermophilus, purified bulk tRNAs from the D. radiodurans R1 and T. thermophilus t6A- mutants were analyzed, and k2C was present both in D. radiodurans and T. thermophilus t6A- strains (Figure 9). LC-MS detection and subsequent MS/MS verification confirmed the presence of k2C at positions 34 in the anticodon loop of the minor tRNAIleCAU in both wild-type and mutant T. thermophilus (Figure 9D-E). Thus, t6A is clearly not a determinant for TilS in these organisms.

Figure 8.

Structural representation of TilS derived from various species. Phyre-generated homology models of TilS from (A) D. radiodurans (full-length, 600 aa), (B) D. radiodurans (truncated, 400 aa), (C) S. mutans and, and (D) Synechocystis sp. using (E) G. kaustophilus TilS (3A2K) in complex with tRNA (blue) as starting structure. Various domains are indicated as well as their respective TilS type. NTD, N-terminal domain; CTD 1 and 2, C-terminal domain 1 and 2.

Figure 9.

Representative LC-MS nucleoside analysis for N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) and lysidine (k2C) isolated from total tRNA of D. radiodurans and T. thermophilus. (A) D. radiodurans wild-type and mutant (ΔtsaD) samples. Extracted ion chromatograms (XIC) for m/z range 412.7-413.7 corresponding to the molecular ion for t6A. (B) D. radiodurans ΔtsaD (XYD) XIC for m/z range 371.7-373.7 corresponding to the molecular ion for k2C [(M=H)+ = 372 Da]. Similar results were found in the D. radiodurans wild-type. (C) MS/MS spectrum obtained from RNase T1 digestion of tRNA from T. thermophilus wild-type and (D) Δttha0793 (ΔtsaC) MS/MS verification of the presence or absence of k2C and t6A in tRNAIleCAU.

Consequences of t6A deficiency on the D. radiodurans proteome

At the phenotypic level, the initial Onodera study had found that t6A deficient D. radiodurans strains were more sensitive to mitomycin C, which induces inter-strand DNA cross-links, but had not observed differences in growth rates between the t6A mutants and the parental strain (Onodera et al., 2013). We reproduced this observation both in microtiter plates and in flasks, although the mutants consistently showed a longer lag time (data not shown). To gain further insight into the proteome changes in response to the absence of t6A, we performed a shotgun proteomics comparison of the D. radiodurans wild-type and ΔtsaD strains at mid-log and late-log growth stages and sample were normalized for protein content. A total of 998 proteins were identified when merging the sixteen samples (4 conditions × 4 biological replicates) and quantified by spectral count. At mid-log growth, 53 proteins were significantly increased in the mutant compared to wild-type, while 68 were decreased (Table 4 and S4). At late-log growth, 103 proteins were significantly increased in the mutant, while 66 were decreased (Table 5 and S5). The most reduced protein in the mutant at mid log is ribosomal protein L27p (DR_0085) (Table 4). The corresponding gene in E. coli is not essential, but mutants have greatly impaired growth rates, and are cold and heat sensitive (Wower et al., 1998). Thus, the absence of any observed growth phenotype in D. radiodurans mutants is surprising, considering that the predicted fitness cost of a DR_0085 deletion is high (Table 4).

Table 4. Peptides significantly changed greater than 2-fold during mid-log growth phase.

Full list of detected peptides can be found in supplementary Table S4. Stress proteins induced >3 fold are in red.

| RefSeq Locus Tag | Functional annotation | Fold Change | pValue | Predicted Fitness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR_0128 | Heat shock protein GrpE | 99.0 | 1.29E-04 | 0.233 |

| DR_0907 | Cold shock protein CspA | 99.0 | 2.71E-03 | 0.043 |

| DR_0989 | cationic outer membrane protein OmpH, putative | 99.0 | 1.24E-02 | 1 |

| DR_0075 | hypothetical protein | 11.7 | 1.75E-03 | 0.922 |

| DR_1705 | hydrolase family protein | 11.5 | 2.50E-03 | 0.775 |

| DR_0630 | Cell division protein FtsA | 10.7 | 3.06E-04 | 0.182 |

| DR_2394 | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase (EC 3.5.1.28) | 7.7 | 1.10E-03 | 1 |

| DR_0651 | Arginase (EC 3.5.3.1) | 7.2 | 5.02E-05 | 1 |

| DR_1447 | hypothetical protein | 6.3 | 1.00E-05 | 1 |

| DR_0608 | Histone acetyltransferase HPA2 and related acetyltransferases | 5.0 | 1.64E-03 | 1 |

| DR_A0047 | Phosphomannomutase (EC 5.4.2.8) / Phosphoglucomutase (EC 5.4.2.2) | 4.9 | 5.94E-03 | 1 |

| DR_B0125 | iron ABC transporter, periplasmic substrate-binding protein | 4.3 | 3.49E-04 | |

| DR_1335 | Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (EC 6.1.1.5) | 3.7 | 3.43E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1063 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (EC 5.2.1.8) | 3.6 | 1.11E-02 | 0.775 |

| DR_1199 | ThiJ/PfpI family protein | 3.5 | 1.08E-02 | 0.922 |

| DR_0640 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (EC 2.5.1.6) | 3.4 | 8.29E-03 | 0.043 |

| DR_A0184 | Pyridoxal kinase (EC 2.7.1.35) | 3.3 | 3.22E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1915 | hypothetical protein | 3.1 | 1.67E-02 | 0.183 |

| DR_2352 | Porphobilinogen deaminase (EC 2.5.1.61) | 3.1 | 2.78E-04 | 1 |

| DR_0105 | hypothetical protein | 2.5 | 4.31E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1422 | hypothetical protein | 2.5 | 9.43E-03 | 1 |

| DR_A0018 | 5′-nucleotidase (EC 3.1.3.5) | 2.5 | 5.20E-03 | 1 |

| DR_0459 | FIG00578356: hypothetical protein | 2.3 | 1.01E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1907 | Predicted L-lactate dehydrogenase, Fe-S oxidoreductase subunit YkgE | 2.3 | 7.41E-03 | 1 |

| DR_B0014 | Vitamin B12 ABC transporter, B12-binding component BtuF | 2.2 | 1.25E-02 | |

| DR_1277 | ABC-type probable sulfate transporter, periplasmic binding protein | 2.0 | 2.14E-03 | 0.043 |

| DR_0006 | Metal-dependent hydrolase (EC 3.-.-.-) | 2.0 | 7.23E-03 | 1 |

| DR_A0299 | copper resistance protein, putative | 2.0 | 5.32E-03 | 0.338 |

| DR_1988 | Phosphate starvation-inducible protein PhoH, predicted ATPase | -2.1 | 1.17E-02 | 1 |

| DR_2346 | 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A ligase (EC 2.3.1.29) | -2.1 | 8.48E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1027 | amino acid ABC transporter, periplasmic amino acid-binding protein | -2.3 | 2.40E-05 | 1 |

| DR_1055 | Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (EC 6.1.1.12) @ Aspartyl-tRNA(Asn) synthetase (EC 6.1.1.23) | -2.5 | 5.21E-03 | 0.705 |

| DR_0921 | Methionine gamma-lyase (EC 4.4.1.11) | -2.5 | 1.59E-02 | 0.043 |

| DR_2123 | Translation initiation factor 1 | -2.5 | 8.73E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1046 | ClpB protein | -3.8 | 1.24E-02 | 1 |

| DR_B0068 | extracellular nuclease, putative | -21.5 | 5.24E-03 | |

| DR_0085 | LSU ribosomal protein L27p | -99.0 | 2.12E-04 | 0.135 |

Table 5. Peptides significantly changed greater than 2-fold during late-log growth phase.

Full list of detected peptides can be found in supplementary Table S5. Stress proteins induced > 3 fold are in red.

| RefSeq Locus Tag | Functional annotation | Fold Change | pValue | Predicted Fitness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR_0651 | Arginase (EC 3.5.3.1) | 99.0 | 2.79E-03 | 1 |

| DR_0907 | Cold shock protein CspA | 99.0 | 6.68E-05 | 0.775 |

| DR_2394 | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase (EC 3.5.1.28) | 43.5 | 1.21E-03 | 0.922 |

| DR_1598 | protease, putative | 12.3 | 3.76E-05 | 0.848 |

| DR_1370 | FIG00579514: hypothetical protein | 11.5 | 1.88E-03 | 1 |

| DR_0009 | Vancomycin B-type resistance protein VanW | 10.0 | 5.56E-03 | 1 |

| DR_0094 | FIG00900003: hypothetical protein | 9.3 | 6.67E-04 | 1 |

| DR_1063 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (EC 5.2.1.8) | 8.8 | 1.49E-04 | 0.848 |

| DR_1891 | tetratricopeptide repeat family protein | 7.3 | 1.93E-04 | 1 |

| DR_1447 | hypothetical protein | 6.9 | 4.41E-05 | 1 |

| DR_0612 | Arginine utilization protein RocB | 5.2 | 3.07E-04 | 1 |

| DR_0606 | Heat shock protein 60 family co-chaperone GroES | 5.0 | 5.71E-04 | 0.182 |

| DR_B0125 | iron ABC transporter, periplasmic substrate-binding protein | 4.7 | 6.12E-03 | |

| DR_A0018 | 5′-nucleotidase (EC 3.1.3.5) | 4.5 | 6.21E-04 | 1 |

| DR_0121 | FIG00578909: hypothetical protein | 4.4 | 4.99E-03 | 1 |

| DR_0640 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (EC 2.5.1.6) | 4.0 | 1.60E-03 | 0.043 |

| DR_1624 | Cold-shock DEAD-box protein A | 3.9 | 2.53E-02 | 0.922 |

| DR_1376 | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (EC 2.4.2.8) | 3.3 | 3.84E-03 | 0.706 |

| DR_1335 | Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (EC 6.1.1.5) | 3.1 | 4.16E-03 | 0.134 |

| DR_A0184 | Pyridoxal kinase (EC 2.7.1.35) | 3.0 | 3.86E-03 | 0.922 |

| DR_0937 | tetratricopeptide repeat family protein | 3.0 | 3.29E-03 | 1 |

| DR_0960 | hypothetical protein | 2.9 | 4.00E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1915 | hypothetical protein | 2.9 | 1.36E-02 | 0.922 |

| DR_A0333 | FHA domain containing protein | 2.8 | 3.59E-02 | 0.922 |

| DR_B0014 | Vitamin B12 ABC transporter, B12-binding component BtuF | 2.8 | 7.90E-04 | |

| DR_1379 | Transcriptional regulator, TetR family | 2.4 | 2.79E-03 | 1 |

| DR_A0299 | copper resistance protein, putative | 2.3 | 8.07E-03 | 0.923 |

| DR_1407 | hypothetical protein | 2.3 | 5.65E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1465 | FIG00577987: hypothetical protein | 2.3 | 5.65E-03 | 1 |

| DR_2278 | amino acid ABC transporter, periplasmic amino acid-binding protein | 2.2 | 1.81E-03 | 0.922 |

| DR_1736 | 2′,3′-cyclic-nucleotide 2′-phosphodiesterase (EC 3.1.4.16) | 2.2 | 9.63E-04 | 0.922 |

| DR_0686 | Conserved repeat domain protein | 2.1 | 8.48E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1748 | FIG00578260: hypothetical protein | 2.1 | 5.80E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1809 | Glycine dehydrogenase [decarboxylating] (glycine cleavage system P protein) (EC 1.4.4.2) | 2.1 | 2.79E-02 | 0.922 |

| DR_0608 | Histone acetyltransferase HPA2 and related acetyltransferases | 2.0 | 4.27E-03 | 1 |

| DR_0302 | Glucosamine--fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase [isomerizing] (EC 2.6.1.16) | -2.0 | 1.59E-03 | 0.338 |

| DR_0113 | oxidoreductase, short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family | -2.0 | 1.88E-04 | 0.922 |

| DR_0456 | MotA/TolQ/ExbB proton channel family protein | -2.0 | 6.70E-03 | 0.775 |

| DR_2221 | Tellurium resistance protein TerD | -2.0 | 1.63E-03 | 0.922 |

| DR_A0005 | Threonine dehydrogenase and related Zn-dependent dehydrogenases | -2.2 | 4.46E-02 | 0.922 |

| DR_0859 | Ribonuclease E inhibitor RraA | -2.2 | 4.40E-02 | 1 |

| DR_A0237 | Periplasmic aromatic aldehyde oxidoreductase, molybdenum binding subunit YagR @ 4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA reductase, alpha subunit (EC 1.3.99.20) | -2.2 | 1.04E-03 | 0.923 |

| DR_1132 | Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase (EC 4.2.1.9) | -2.2 | 3.68E-03 | 0.922 |

| DR_1544 | Butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (EC 1.3.99.2) | -2.2 | 8.73E-03 | 1 |

| DR_0085 | LSU ribosomal protein L27p | -2.3 | 3.70E-02 | 0.135 |

| DR_2510 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase (EC 4.2.1.17) | -2.5 | 1.00E-05 | 1 |

| DR_1778 | 3-isopropylmalate dehydratase large subunit (EC 4.2.1.33) | -2.6 | 6.92E-05 | 0.847 |

| DR_2346 | 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A ligase (EC 2.3.1.29) | -2.6 | 1.55E-03 | 0.775 |

| DR_0362 | D-alanine--D-alanine ligase A (EC 6.3.2.4) | -2.7 | 3.15E-02 | 0.232 |

| DR_1074 | (3R)-hydroxymyristoyl-[acyl carrier protein] dehydratase (EC 4.2.1.-) | -2.7 | 4.27E-04 | 0.284 |

| DR_0265 | Predicted transcriptional regulator of N-Acetylglucosamine utilization, GntR family | -2.8 | 5.32E-03 | 1 |

| DR_1082 | Ribosomal subunit interface protein | -2.9 | 1.25E-04 | 0.922 |

| DR_2033 | Glutamine synthetase type III, GlnN (EC 6.3.1.2) | -3.3 | 1.24E-04 | 1 |

| DR_1055 | Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (EC 6.1.1.12) @ Aspartyl-tRNA(Asn) synthetase (EC 6.1.1.23) | -3.4 | 1.21E-04 | 1 |

| DR_1027 | amino acid ABC transporter, periplasmic amino acid-binding protein | -3.7 | 1.61E-05 | 0.922 |

| DR_1988 | Phosphate starvation-inducible protein PhoH, predicted ATPase | -4.2 | 3.02E-03 | 0.922 |

| DR_1072 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (EC 2.3.1.9) | -5.0 | 1.07E-02 | 1 |

| DR_1645 | UDP-N-acetyl-D-mannosaminuronic acid transferase | -6.0 | 3.24E-03 | 0.847 |

| DR_B0068 | extracellular nuclease, putative | -9.3 | 4.56E-04 | |

| DR_0459 | FIG00578356: hypothetical protein | -99.0 | 1.00E-05 | 1 |

Using the MetaCyc Omics viewer (Caspi et al., 2014), enrichments in the down-regulated genes for the acetyl-coA to butyrate fermentation pathway (P-value: 2 × 10-4) and isoleucine degradation pathway (P-value: 8 × 10-4) were observed in the late-log experiment. No pathway enrichment with P-values < 10-3 were observed in the up-regulated genes using the MetaCyc Omics viewer. As stress is not well covered by the MetaCyc pathway enrichment tools, we performed a manual analysis that revealed that >20% (4/19 in the mid-log and 5/21 in the late-log sets) of the proteins whose expression levels increased over three-fold in the t6A- strains were related to protein homeostasis or other types of stress (Table 4 and 5). A total of 83 stress proteins have been catalogued in D. radiodurans R1 [Table 3 of (Makarova et al., 2001)], and while this is certainly an underestimation, it still represents 2.5% (83 of 3261 CDS) of the D. radiodurans theoretical proteome. Hence, stress proteins are significantly enriched in the mutant (χ2, P > 0.001). These include chaperones [DR_0128 (GrpE) and DR_0606 (GroES)], the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (EC 5.2.1.8) protein (DR_1063), and the cold-shock DEAD-box protein (DR_1624). Arginase (DR_0651) is also highly induced at both mid-log and late log-growth in the t6A-deficent strain. Increasing arginase lowers nitric oxide (NO) levels, and it has been shown that NO up-regulates transcription of obgE, a gene involved in bacterial growth proliferation and stress response in D. radiodurans (Patel et al., 2009).

To assess if proteins whose levels are reduced in the t6A- strains are enriched in t6A (ANN) codons, several types of analyses were performed as detailed in the supplemental results section. We investigated enrichment of t6A dependent Ser and Arg codons, as well as abundance of and length of stretches of t6A dependent codons in all D. radiodurans coding sequences (Tables S6-S9). In summary, there was a small general enrichment of t6A dependent codon stretches in down-regulated proteins, but the significance of this observation is not clear. However, a few down-regulated proteins were clearly enriched in t6A codons. For example ClpB (DR_1046) has a stretch of seven t6A dependent codons (Table S8) and its expression was reduced nearly 4-fold in the t6A mutant (Table 4).

Discussion

Maintaining t6A in tRNA must confer a fitness advantage as its biosynthetic pathway is present in genomes of all self-replicating organisms sequenced to date (Thiaville et al., 2014b). The consequences of t6A deficiency, however, vary greatly from one kingdom to another and even from one clade to another. Additionally, t6A synthesis genes could play additional roles in the cell unrelated to t6A biosynthesis, making the study of the genes very difficult. Here, we focused on the essentiality phenotype of t6A- strains in bacteria and showed that while t6A is essential in most bacteria this is not a universal feature of the kingdom. An obvious practical consequence of this observation is that antibacterial compounds targeting this pathway may not be broad spectrum, although in most organisms of clinical interest t6A is essential.

Notably, we clearly demonstrate that t6A is a positive determinant of the E. coli IleRS for charging the major tRNAIleGAU. Previous work from the Suzuki laboratory demonstrated that this modification, in combination with k2C, is a determinant of both E. coli and M. mobile IleRS for the charging of the minor tRNAIleCAU (Taniguchi et al., 2013). Because t6A is not required for charging by yeast IleRS, this may be the basis for the bacteria-specific essentiality of t6A. However, the presence of a eukaryotic type IleRS in some bacteria, such as members of the Thermus-Deinococcus clade, may circumvent the necessity of t6A. Additional mechanisms circumventing this requirement in bacterial-like IleRS could occur and further biochemical characterization of the IleRS/tRNAIle pairs of S. mutans and Synechocystis will be required to test whether t6A is also a determinant for IleRS in these organisms. Kinetic measurements showing that transcripts are very poor substrates for Streptococcus pneumoniae IleRS suggest that t6A may be a determinant for IleRS in Streptococci (Shepherd & Ibba, 2014).

We also show that E. coli tRNAIleCAU requires t6A for efficient lysidinylation by E. coli TilS in vitro. Ikeuchi et al. compared the kinetics of lysidinylation of purified E. coli tRNAIleCAU lacking lysidine but possessing all the other modifications (s4U8, Gm18, D20a, D20b, t6A37, ψ39, m7G46, acp3U47, T54, and ψ55) to that of unmodified tRNAIleCAU prepared by in vitro run-off transcription and concluded that none of the other modifications are strictly required for lysidine formation in vitro (Ikeuchi et al., 2005). However, mutation of A37 to G37 has been shown to reduce the kcat/Km ∼15-fold (Ikeuchi et al., 2005), suggesting that A37 may play an in lysidinylation of tRNAIleCAU, and we show here a significant enhancement in the rate of lysidine formation in the presence of t6A. Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate that t6A enhances the efficiency of TilS.

At odds with the data from E. coli TilS is the observation that in species such as Deinococcus, k2C is present in t6A deficient mutants. Two types of TilS have been structurally characterized. The type I enzymes, exemplified by E. coli TilS, comprise an N-terminal domain (NTD) and two C-terminal domains (CTD1, CTD2), while the type II enzymes possess the NTD and only CTD1 (Ikeuchi et al., 2005, Soma et al., 2003). A study on the molecular basis of recognition and catalysis of types I and II TilS enzymes revealed variances in recognition elements owing to the difference in CTDs (Nakanishi et al., 2005). In type I enzymes a large conformational change accompanies tRNA binding, a phenomenon that is not observed in type II enzymes. Type I TilS recognizes the base pairs C4-G69 and C5-G68 in the acceptor stem of tRNAIleCAU via CTD2, which induces allosteric changes on the NTD for optimum positioning of C34 in the active site for lysidinylation (Ikeuchi et al., 2005, Nakanishi et al., 2005, Suzuki & Miyauchi, 2010). D. radiodurans TilS belongs to a subset of type 1 enzymes that harbor a putative cytidine deaminase encoded C-terminal to CTD2 (Figure 8). The structure for this TilS subtype is yet to be solved. A homology model of the D. radiodurans TilS was generated using Geobacillus kaustophilus TilS as the starting structure (PDB: 3A2K). The homology model of full length D. radiodurans TilS shows deviations in folding from G. kaustophilus TilS, notably in the NTD and CTD2, likely due to the presence of the extra domain. Interestingly, upon deletion of the putative cytidine deaminase domain, the NTD and CTD1 domains adopt identical folding as G. kaustophilus TilS, while the CTD2 remains distorted. Thus, the mechanism of tRNA recognition by D. radiodurans TilS may differ from that of type I and II TilS due to the presence of an extra domain, which may account for t6A independence.

In addition to a role as determinants for IleRS and possibly TilS, t6A directly influences translational fidelity and could be especially important for the translation of specific, essential proteins. We have previously shown in yeast that more frame-shifting occurs in proteins that have stretches of t6A dependent codons (El Yacoubi et al., 2011). Interestingly, analysis of the D. radiodurans genome revealed a low use of AUA codons (0.09% of all codons) as compared to E. coli (0.42%) and H. volcanii (0.22%). In fact, D. radiodurans rarely uses an A or U in the third position of any codon. As a consequence, there is only one putative essential gene (DR_2087, Table S9) in D. radiodurans that possesses two consecutive AUA codons. The gene encodes translation initiation factor IF3, which is reduced 1.8 fold in the t6A– strain at mid-log (Table S4). However, the AUA codon usage for Synechocystis and S. mutans (0.44% and 0.78%, respectively) is similar to E. coli, and instances of sequential AUA codons are found in ∼80 genes in both Synechocystis and S. mutans (Tables S13 and S14, respectively), similar to E. coli (79 genes with runs of AUA codons, Table S15), hence low usage of AUA codons cannot be the sole factor explaining the dispensability of t6A. Interestingly, while many of the genes with runs of AUA codons in E. coli and S. mutans are involved in essential processes, in Synechocystis the genes are mainly mobile elements or hypothetical genes (Tables S13-S15).

Recent systems level approaches integrating proteomics, codon usage, and modification profiling (Dedon & Begley, 2014, Gu et al., 2014), mainly in eukaryotes, have shown that modifications can modulate the expression of specific genes or gene sets under stress. For example, exposure of yeast to the alkylating agent methylmethane sulfonate (MMS) causes increases in wobble mcm5U in tRNAArgUCU that leads to enhanced translation of proteins from AGA-enriched genes (Begley et al., 2007, Patil et al., 2012a, Patil et al., 2012b), while H2O2-induced stress increases the wobble m5C in tRNALeuCAA, leading to increased translation of mRNAs for UUG-enriched genes (Chan et al., 2012). Both the threonine degradation enzyme 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A ligase (EC 2.3.1.29) and the isoleucine degradation enzyme 3-isopropylmalate dehydratase large subunit (EC 4.2.1.33) are reduced 2.6 fold in the t6A- strain and have stretches of over five t6A dependent ANN codons (Table S4 and S5). This could be a regulatory response if inhibiting isoleucine or threonine degradation (threonine is the isoleucine precursor) was a mechanism to compensate for poor charging of target tRNAs by IleRS when t6A is low. Further experiments are required to evaluate if the lower amounts of these catabolic enzymes are caused by poor translation of the ANN codons or by other regulatory mechanisms.

Our analysis of the D. radiodurans t6A- proteome does suggest that the in vivo role of t6A in translation is going to be difficult to decipher because of the number of tRNAs involved (12 tRNAs are modified in E. coli) and the absence of a systematic understanding of the effects of t6A on tRNA levels, decoding efficiency and accuracy in vivo. More generally, the difficulty in elucidating the molecular basis for the essentiality or phenotypic consequences of t6A deficiency stems from the combination of direct and indirect effects that are difficult to separate. An obvious indirect effect is the induction of heat-shock proteins that fits with the emerging realization that, in yeast, the absence of modifications in the anticodon loop results in mistakes in protein synthesis, leading to misfolding and activation of the proteotoxic response in yeast (Patil et al., 2012a, Patil et al., 2012b, Rezgui et al., 2013, Nedialkova & Leidel, 2015). Our results suggest that this might also be the case for t6A, but further experimental work is required to assess if and how the absence of this modification leads to protein misfolding in D. radiodurans and in other organisms.

In conclusion, this work has laid the foundation for understanding the essentiality of t6A in Bacteria. We have clearly shown that there is not one unique cause for essentiality, and for some organisms such as E. coli, there may be multiple causes making antibacterial agents directed against t6A biosynthesis quite effective since target-based resistance mechanisms should not occur. In contrast, organisms such as S. mutans may not be sensitive to antibacterial agents targeting t6A biosynthesis, and the underlying mechanism that makes t6A dispensable in these organisms will require detailed biochemical studies.

Experimental Procedures

Bioinformatics

All genomes were downloaded from the PATRIC database (Wattam et al., 2014). To examine the codon usage of whole genomes, a Java script located at http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/codon_usage.html platform (Stothard, 2000) was modified. This modified script takes a fasta file containing the CDS for a whole genome and returns, for each CDS, counts of each codon and frequency per 1000 codons. Tabulation of counts and figures were performed using Excel. Codon usage was also calculated using the Gene-Specific Codon Counting Database at http://www.cs.albany.edu/∼tumu/GSCC.html (Tumu et al., 2012). To find specific codons or runs of specific codons, an in-house Perl script based on a previously published C+ program was used (El Yacoubi et al., 2009). This program takes a fasta file and returns two results. One result is the location of any codon requested in the submitted fasta file. The second output returns runs of codons for each CDS, including length of the codon run and the number of occurrences of each run. Pathway enrichments were generated using the Metacyc omics viewer using the default parameters (Caspi et al., 2014). The E. coli essentiality data was derived from Ecogene (Zhou & Rudd, 2013) and the D. radiodurans fitness data was extracted from http://cefg.uestc.edu.cn/ifim/index.php. The Phyre platform was used to generate the homology model of the D. radiodurans TilS using standard parameters (Kelley & Sternberg, 2009).

Media and strains and genetic manipulations

All strains, plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S1, Table S2, and Table S3 respectively. Bacterial growth media were solidified with 15 g/l agar (BD Diagnostics Systems) for the preparation of plates. E. coli were routinely grown on LB medium (BD Diagnostics Systems) at 37 °C unless otherwise stated. Transformations were performed following standard procedures. IPTG (100 μM), Ampicillin (Amp, 100 μg/ml), Kanamycin (Km, 50 μg/ml), l-Arabinose (Ara, 0.02–0.2%), and Chloramphenicol (Cm, 35 μg/ml) were used when appropriate. M9 Minimal medium (Sambrook et al., 1989), 0.1% (w/v) glucose was used with 20 μg/ml phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan added when needed. P1 transduction was performed following the classical methods (Miller, 1972). Transductants from VDC5801 and VDC5684 into E. coli B and C600 were checked by PCR for transduction of the PTET allele into the recipient strains using primer pairs Ptet2771-fwd/ygjD661-rev and Ptet2771-fwd/yrdC573-rev respectively. T. thermophilus HB8 was grown at 70 °C in TR medium (0.4% (w/v) tryptone (Difco), 0.2% (w/v) yeast extract (Oriental Yeast, Tokyo), and 0.1% (w/v) NaCl (pH 7.5) (adjusted with NaOH)). To prepare plates, 1.5% (w/v) gelatin gum (Wako, Osaka, Japan), 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 1.5 mM MgCl2 were added to the TR medium. D. radiodurans was grown in TGY media (0.5% (w/v) tryptone, 0.1% (w/v) glucose, and 0.3% (w/v) yeast extract (all from Difco) at 30 °C. S. mutans was grown in BHI media (Difco) at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Sequencing

tRNA genes from D. radiodurans were amplified by PCR using oligos listed in Table S3. PCR products were Sanger-sequenced by the University of Florida Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research. Sequences were compared to wild-type sequences using Blast at NCBI.

Disruption of TttsaC

The tsaC null mutant of Thermus thermophilus HB8 (ΔTtTsaC) was generated by substituting the target gene (TTHA0793, gi:55980762) with the thermostable kanamycin resistance gene (HTK) through homologous recombination as described previously (Hashimoto et al., 2001). The plasmid for gene disruption (PD010793-01) was a derivative of the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), constructed by inserting HTK flanked by 500-bp upstream and downstream sequences of the target gene. The transformation of T. thermophilus HB8 was performed by the following procedure (Hashimoto et al. 2001). An overnight culture was diluted 1:40 with TR medium and shaken at 70 °C for 2 h. This culture (0.4 ml) was mixed with 2 μg of the plasmid DNA, incubated at 70 °C for 2 h, and then spread on plates containing 500 μg/ml of kanamycin, which were incubated at 70 °C for 15 h. A colony was selected, cultured in TR medium, and spread on plates containing 500 μg/ml of kanamycin again, to remove the heteroplasmic recombinant cells completely, as T. thermophilus is a polyploid organism (Ohtani et al., 2010). Gene disruption was confirmed by PCR amplification, using the isolated genomic DNA as the template (Figure 7).

Source of aminoacylation and modification enzymes used in this study

A total S100 aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase extract (free of tRNAs) from yeast provided by T. A. Weil (Klekamp & Weil, 1982) and purified His6-tagged E. coli IleRS and TilS (Köhrer et al., 2008) were available as laboratory stocks. The TsaBCDE enzymes were purified as described previously (Deutsch et al., 2012).

Construction of tRNA Templates for in vitro transcription

The templates for producing tRNAIle transcripts were produced via a Klenow extension reaction as described (Deutsch et al., 2012) with the primers FtRNAIle(cat), RtRNAIle(cat), FtRNAIle(gat), and RtRNAIle(gat) listed in Table S3.

RNA Transcription and Purification

Transcription reactions to produce RNA were run for 4 hours at 37 °C in 80 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 2.0 mM spermidine, 24 mM MgCl2, 2.0 mM NTPs, 300 pmol template, and 2.5 μg of T7 polymerase. Prior to reactions the templates were heated to 95 °C for five minutes and allowed to cool slowly to room temperature over one hour. The RNA products generated in the transcription reactions were precipitated by the addition of 0.1 volume ammonium acetate (8.0 M), three volumes of 100% ethanol, and cooling at −80 °C for 30 minutes, then pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4 °C. After removing the supernatents, the pellets were resuspended in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 2.0 mM EDTA, the solutions mixed 1:1 with formamide, boiled for five minutes, and snap cooled on ice before being purified via urea-PAGE electrophoresis (10% acrylamide). The RNA was extracted from the gel by crush and soak, then precipitated as above, and suspended in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 2 mM EDTA.

In vitro RNA Modification with TsaBCDE

Purified tRNA was converted to t6A-modified tRNA in reactions containing 5 μM TsaBCDE, 5.0 mM threonine, 5.0 mM bicarbonate, 10 mM ATP, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 1.0 mM MnCl2, 1.0 μM ZnCl2, 50 μM tRNA, and 5mM DTT at 37°C for 20 minutes. To monitor the extent of modification, reactions were run in parallel containing 500,000 DPM [14C]-L-threonine diluted to 5.0 mM with unlabeled threonine. The reactions were then extracted with phenol/chloroform, and the tRNA precipitated and suspended as described above. tRNA from reactions containing [14C]-L-threonine were then analyzed using scintillation counting to quantify the extent of modification. Under these assay conditions the extent of modification plateaued after 20 minutes, measuring 60% for tRNAIleCAT and 51% for tRNAIleGAT.

In vitro aminoacylation of tRNA with isoleucine

0.5 – 1 A260 (16-32 μM) of bulk tRNA or 0.01 – 0.025 A260 (0.32-0.8 μM) of tRNA transcripts were aminoacylated in vitro in 50 μl-reactions with L-isoleucine using purified E. coli IleRS (0.5 μM) or total S100 extracts (5 μg) prepared from yeast. Reaction mixtures were as follows: (i) 50 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, 0.1 μg/μL BSA, and 5 μM L-[3H]-isoleucine (ARC; ∼60 Ci/mmole) using E. coli IleRS; (ii) 50 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, 5 mM DTT, 0.1 μg/μL BSA, and 5 μM L-[3H]-isoleucine (ARC; ∼60 Ci/mmole) for use with yeast extracts. Prior to the addition of enzymes, tRNAs were pre-incubated at 65 °C for 3 minutes, transferred to 37 °C for 10 minutes and then left at room temperature for 5 minutes. Aminoacylation reactions were carried out at 37 °C for 60 min. At various time points, aliquots were removed and analyzed by precipitation with TCA followed by liquid scintillation counting of TCA-precipitatable counts. TCA-precipitatable counts were normalized per 1 A260 of tRNA (1600 pmoles) for all experiments. Background (obtained from reactions run without tRNA) was subtracted from all values. All assays were carried out at least in triplicate.

In vitro modification of tRNA with lysidine

The in vitro modification of C34 to lysidine using purified E. coli TilS has been described (Köhrer et al., 2008). 0.01 – 0.025 A260 (0.32-0.8 μM) of tRNA transcript was modified in a 50 μl-reaction containing 50 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 10 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, 0.1 μg/μL BSA, 3.54 μM L-[3H]-lysine (Perkin Elmer; ∼84.8 Ci/mmole) and 0.5 μM E. coli TilS. Inorganic pyrophosphatase (New England Biolabs) was added to the reaction at a concentration of 0.04 U/μl. The modification reactions were carried out at 37 °C for 60 minutes. The pre-incubation of tRNA and the analysis of incorporation of radiolabeled amino acid into tRNA were as described above. Assays were carried out in triplicate.

Preparation of bulk tRNA and detection of t6A

Bulk tRNA was extracted from S. cerevisiae, E. coli strains, Synechocystis PCC 6803, and S. mutans strains as previously described (El Yacoubi et al., 2009). D. radiodurans was subcultured 1:100 from a starter culture into 1 L of TGY and grown at 30°C until the culture reached late-log at an OD600 of 2.5. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The weight of the cell pellet was determined, and the cells were suspended in 95% ethanol at 0.1 volumes/g of dry weight to remove the S-layer. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation as before, and the pellets were suspended in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5 at 3 mL/g of cell weight. Zymolyase was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/mL and the samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes. Following the incubation, a volume of acidic-buffered phenol (pH 5.5), equal to the amount of 50 mM sodium acetate added previously, was added and the sample was incubated at 70 °C for 30 minutes. The sample was then cooled to room temperature prior to centrifugation at 4000 x g for 10 minutes at RT. The aqueous layer was transferred to a new tube, and an equal volume of 25:24:1 acidic-buffered phenol (pH 5.5):chloroform:isoamyl alcohol was added, mixed, and the sample was centrifuged again at 4000 x g for 10 minutes at RT. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, and to it, an equal volume of chloroform was added, mixed, and the sample was centrifuged again. The aqueous phase was transferred, and sodium chloride was added to a final concentration of 1 M and 0.2 volumes of isopropanol were added. The sample was mixed well, incubated at −20 °C for 1 hour, and centrifuged at 8000 x g for 20 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and 0.6 volume of isopropanol was added to the supernatant, and the sample was incubated overnight at -20 °C. The next day, the samples were allowed to warm on ice for 10 minutes prior to centrifugation at 8000 x g for 20 minutes at 4 °C. The pellet was washed with 20 mL of 80% v/v ethanol, and centrifuged at 8000 x g, before drying the pellet in a CentriVap Concentrator (Labconco, Kansas City, MO) for 30 minutes at 40 °C, and the RNA was recovered by ethanol precipitation. The final pellets were suspended in 200 μL TE and stored at −20 °C. All tRNA extractions were performed in triplicate from independent cultures.

Nucleoside preparations were prepared by incubating 100 μg of linearized bulk tRNA with 10 units of Nuclease P1 (Sigma) in 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.3) overnight at 37°C. The next day, 0.1 volume of 1 M ammonium bicarbonate (pH 7.0) was added to give a final concentration of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. 0.01 units of Phosphodiesterase I (Sigma) and 3 μL E. coli alkaline phosphatase (Sigma) were added, and the samples were incubated for an additional 2 hours at 37 °C. The hydrolyzed nucleosides were further purified by filtering through a 5 kD MWCO filter (Millipore) (to remove enzymes), dried in a CentriVap Concentrator, and suspended in 20 μL of water prior to analysis by HPLC or LC-MS/MS. Nucleoside preparations were prepared as previously described using Nuclease P1 (Sigma) Phosphodiesterase I (Sigma), and E. coli alkaline phosphatase (Sigma) (El Yacoubi et al., 2009).

HPLC and LC-MS/MS Analysis

t6A was detected by HPLC as described by (Pomerantz & McCloskey, 1990) using a Waters 1525 HPLC with Empower 2 software and detected with a Waters 2487 UV-vis spectrophotometer at 254 nm. Separation was performed on an Ace C-18 column heated to 30 °C, using 250 mM ammonium acetate (Buffer A) and 40% acetonitrile (Buffer B) run at 1 mL/min. 100 μg of nucleosides were injected and separated using a isocratic complex step gradient. Levels of t6A were measured by integrating the peak area from the extraction ion chromatograms. The ratios of Ψ-modified base/m22G were used to normalize for tRNA concentration across samples. Levels for mutant strains were expressed relative to wild-type levels. Results were confirmed by LC–MS/MS at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, St. Louis MO. The MS/MS fragmentation data, as well as a t6A standard provided by D. Davis (University of Utah) were also used to confirm the presence of t6A.

Detection of k2C

Prior to enzymatic digestion, the tRNA was denatured at 100 °C for 3 min then chilled in an ice water bath. To lower the pH, 1/10 volume of 0.1 M ammonium acetate (pH 5.3) was added. For each 0.5 absorbency unity (AU) of tRNA, 2 units Nuclease P1 (Sigma) was added and incubated at 45 °C for 2 h. The pH was readjusted by adding 1/10 volume of 1.0 M ammonium bicarbonate, then 0.002 units of snake venom phosphodiesterase was added and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Finally, 0.5 units of Antarctic phosphatase (New England Biolabs) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The nucleoside digests were stored at -80 °C for further analysis.

The nucleoside digests were analyzed using a Hitachi D-7000 HPLC system with a LC-18-S (Supelco) 2.1 × 250 mm, 5 μm particle column with a flow rate of 300 μL/min, connected directly to the mass spectrometer. Mobile phases used were as follows: 5mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.3 and 40% acetonitrile in water. The column eluent was split immediately after the column, 1/3 to the electrospray ion source and 2/3 to the UV detector. The gradient used follows that previously described (Russell & Limbach, 2013).

Mass spectral data was acquired on a Waters G2-S ion mobility time-of-flight mass spectrometer operated in sensitivity mode using MSE data collection. The ion source parameters included a capillary voltage of 2.5 kV, sampling cone voltage of 40 V offset by 80 V with a temperature of 200°C, desolvation gas at a rate of 500L/hour and a nebulization pressure of 6 Bar. The ion mobility parameters were set using helium gas with a start wave height at 10 V ending at 40 V at a wave velocity starting at 1000 m/s and ending at 500 m/s. To avoid nucleoside fragmentation prior to detection, the bias energy was adjusted to 45 eV at the trap and 3 eV at the ion transfer. Fragmentation was obtained by ramping the transfer energy (post ion mobility and prior to TOF analysis) from 15 to 45 eV. Low and high energy MS and MS/MS spectra were verified and time-aligned in Drift Scope™ ver 4.2. Masses were adjusted using the Lock Spray™ collected once every 30 s for 500 msec with the calibrant Leucine Enkephalin. Data analysis was performed using Masslinx™ ver 4.1.

Oligonucleotide Analysis

Total tRNA for all strains was analyzed as previously described (Puri et al., 2014). Total tRNA was incubated with 50 U of RNase T1 (Worthington Biochemical) per mg of tRNA in 20 mM ammonium acetate for 2 h at 37 °C. Digestion products were separated using an XBridge™ C18 column (100 mm × 2 mm; 1.7μm, 120Å) from Waters (Santa Clara, CA.) with a Hitachi La Chrome Ultra UPLC containing two L-2160U pumps, L-2455U diode array detector and an L-2300 column oven (35 °C) connected in-line with a Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA) LTQ™ linear ion trap mass spectrometer. Before each run the column was equilibrated for 10 min at 95% Buffer A (200 mM hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), 8.6 mM triethylamine (TEA), pH 7) and 15% Buffer B (200 mM HFIP, 16.3 mM TEA: methanol, 50:50 v:v, pH 7). The gradient started at 10 %B and increased at 8 % min-1 for 10 min. The mobile phase was then increased to 95% for 5 min before re-equilibrating prior to the next analysis. The mass spectrometer operating parameters included a capillary temperature of 275 °C, spray voltage of 4 kV, source current of 100 μA, and sheath, auxiliary and sweep gases set to 40, 10 and 10 arbitrary units, respectively.

Each RNase digestion reaction was analyzed four times using an MS scan range of 600-2000. Each instrumental segment consisted of a full scan, collected in negative polarity, followed by three product ion scans (scans 2-4). Product ion scans were obtained using data dependent collision-induced dissociation (CID) at a normalized collision energy of 35% with an activation time of 10 ms. In data dependent mode, scans 2-4 were triggered by the three most abundant ions from scan 1 and isolated by a mass width of 2 (±1 m/z). Each ion selected for CID was analyzed for up to 10 scans before it was added to a dynamic exclusion list for 15 s (typical chromatographic fwhm) for both modes of data acquisition. Each RNase digestion reaction was also analyzed four times using an MS scan range of 800-1200. This smaller scan range was accompanied by a targeted MS/MS list intended to maximize the opportunity to obtain full sequence coverage. Wild type T. thermophilus tRNAIleCAU was purified from total tRNA using a biotinylated deoxyribonucleotide probe complementary to the 3′-end of the tRNA and analyzed as described above. Examination of the tRNAIleCAU anticodon modification profiles for the Sua6 knockout and D. radiodurans samples was performed using a targeted MS/MS approach (Wetzel & Limbach, 2013) with a scan range of 800-1200 on RNase T1 digested total tRNA.

Proteomics