Abstract

Background

Inhibitors of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) alleviate pain and reduce fever and inflammation by suppressing biosynthesis of prostacyclin (PGI2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). However, suppression of these PGs, particularly PGI2, by COX-2 inhibition or deletion of its I prostanoid (Ip) receptor also predisposes to accelerated atherogenesis and thrombosis in mice. By contrast, deletion of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (mPGES-1) confers analgesia, attenuates atherogenesis and fails to accelerate thrombogenesis, while suppressing PGE2, but increasing biosynthesis of PGI2.

Methods

To address the cardioprotective contribution of PGI2, we generated mice lacking the I prostanoid (Ip) receptor together with mPges-1 on a hyperlipidemic background (LdlR KOs).

Results

mPges-1 depletion modestly increased thrombogenesis, but this response was markedly further augmented by coincident deletion of the Ip (n= 10–18). By contrast, deletion of the Ip had no effect on the attenuation of atherogenesis by mPGES-1 deletion in the LdlR KOs (n= 17–21).

Conclusions

While suppression of PGE2 accounts for the protective effect of mPGES-1 deletion in atherosclerosis, augmentation of PGI2 is the dominant contributor to its favorable thrombogenic profile. The divergent effects on these PGs suggest that inhibitors of mPGES-1 may be less likely to cause cardiovascular adverse effects than NSAIDs specific for inhibition of COX-2.

Keywords: COX-2, mPGES-1, PGI2, PGE2, thrombosis, atherogenesis

Introduction

Interest in the development of small molecule inhibitors of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (mPGES-1) has been fueled by evidence of increased adverse cardiovascular events from the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 1, 2. Inhibitors of COX-2 relieve pain, fever and inflammation by suppressing biosynthesis of prostacyclin (PGI2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)3. However, suppression of these PGs, particularly PGI2, by COX-2 inhibition or deletion also predisposes to accelerated atherogenesis and thrombosis in mice4. Consistent with this, deletion of the I prostanoid receptor (Ip) for PGI2 accelerates atherogenesis in hyperlipidemic mice and enhances thrombogenesis4, 5. By contrast, deletion of mPges-1 confers analgesia6, 7, attenuates atherogenesis8 and does not predispose mice to thrombogenesis4, while suppressing PGE2, but increasing biosynthesis of PGI2. The rediversion of the mPGES-1 substrate, PGH2, to other prostanoids consequent to mPGES-1 inhibition may contribute to cardiovascular efficacy9. Indeed, experimental evidence from mice lacking mPges-1 points to the therapeutic potential of this strategy in ischemic stroke10, abdominal aortic aneurysm11 and vascular proliferation following injury12. Here, we sought to determine the relative contribution of suppressing PGE2 vs augmenting PGI2 to the impact of mPges-1 depletion in hyperlipidemic mice.

Material and Methods

Materials

All reagents used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

Generation of Prostacyclin Receptor Knockout (Ip KO) and Microsomal Prostaglandin E Synthase 1 Knockout (mPges-1 KO) Hyperlipidemic Mice

Ip and mPges-1 KOs were generated on a hyperlipidemic background by crossing them with mice lacking the low density lipoprotein receptor (LdlR KOs :Jackson Laboratory) that were inter-crossed to breed Ip +/−/ mPges-1 +/−/ LdlR KOs. The heterozygous mice were intercrossed to produce LdlR KOs, Ip/ LdlR DKOs, mPges-1/ LdlR DKOs, and Ip/ mPges-1/ LdlR TKOs. Loss of Ip, mPges-1 and LdlR alleles were assessed by PCR analyses. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analyses showed that our mouse models achieved at least 97% purity on the C57BL/6 background. Mice of both genders were fed a high fat diet (HFD, 21.2% fat, 0.2% cholesterol, TD.88137, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) from 8 weeks of age for 3 or 6 months. Mice were weighed before and after the HFD feeding. All animals in this study were housed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania. All experimental protocols were approved by IACUC.

Macrovascular Thrombosis: Photochemical Vascular Injury

The experimental procedures for this model were described previously4. Briefly, animals were anesthetized and secured on a thermal pad at 37°C. A midline cervical incision was made to locate the right common carotid artery. The artery was separated from the vein and a Doppler flow probe (Model 0.5 VB, Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) was applied. The probe was connected to a flowmeter and a computerized data acquisition program (Powerlab, AD Instruments, CO). Rose Bengal (100 μl/ mg) dissolved in saline was injected into the jugular vein of a mouse (50 mg/ Kg BW) and a 1.5mW green light laser (540nm) was directed at the desired site of injury on the exposed carotid artery from a distance of 5cm to induce thrombosis. Blood flow was monitored for up to 120 mins and occlusion time was recorded when blood flow was reduced to zero for up to 5 min.

Microvascular Thrombosis: Laser-Induced Thrombus Formation and Intravital Microscopy

Experiment procedures were performed as described by Yu and colleagues13. Briefly, anesthetized mice were kept at 37°C on a thermal pad. Circulating platelets were fluorescently labeled with rat anti-mouse CD41 (20 μg/ml, 100BD Pharmingen, #553847) and Alex-Flour 488 chicken anti-rat IgG (180 μg/ml, Life Technologies, #A21470) diluted in PBS. The antibody solution (4 μl/ g BW) was injected via pectoral muscle into the jugular vein. The scrotum was cut and the cremaster muscle was exteriorizd, pinned over the microscopy stage, and bathed in a bicarbonate-buffered saline aerated with 95% N2 and 5% CO2 at 37°C.

SlideBook 4.2 imaging software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) was used to control all parts of the intravital microscope and data collection. Arteriolar injury in the cremaster muscle was induced with a fluorescence resonance energy transfer/ fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRET/FRAP) photo-ablation system in which the laser was tuned to 440 nm, focused through the microscope objective, parfocal with the focal plane, and aimed at the vessel wall. The nitrogen dye laser pulsed two times at ~70% power. Successive thrombi were generated either upstream of the previous thrombus or in different arterioles within the same cremaster preparation.

Digital images of thrombus formation were obtained with an Olympus BX61WI microscope. Wide-field fluorescence microscopy was attained with a 2-Galvo high-speed wavelength changer equipped with a high-intensity 300-W xenon light source. Different excitation filters (360, 480, 575, and 655nm) were used in this system. For wide-field imaging, light was amplified up to 1000-fold with a Hamamatsu image intensifier. High-resolution (1390 × 1024) images were captured with a Hamamatsu C9300-201 charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. A Uniblitz shutter on the transmission light source was adjusted to open and close in 50ms. This allowed us to collect both bright field and fluorescence images.

Image Analysis

Image analysis was also performed with SlideBook 4.2 software, using a series of modules that allowed image reconstruction, deconvolution, statistics, and volume analysis. To quantify the thrombosis, we calculated the mean background intensity of each image as the average pixel intensity in a defined region of the blood vessel just upstream of the injury and developing thrombus. The circulating fluorescent antibody was the major contributor to the mean background fluorescence. The area of the thrombus was defined as the total number of pixels with fluorescence greater than the average maximal upstream fluorescence during the course of the image capture. To correct for background fluorescence, the mean upstream fluorescence intensity was multiplied by the area of the thrombus at each time point. The volume of the thrombus was defined as the number of voxels in all planes at a given time point with fluorescence greater than the maximal background fluorescence.

Blood Pressure Measurement Using Tail-Cuff System for High Fat Diet Fed Mice

Systolic blood pressure was measured in conscious mice using a computerized non-invasive tail-cuff system (Visitech Systems, Apex, NC) as described4. Blood pressure was recorded once each day from 8am to 11am for 5 consecutive days after 3 days of training. Average systolic blood pressure was reported.

Preparation of Mouse Aortas and En Face Quantification of Atherosclerosis

After 3 or 6 months on a HFD, mice were transferred to clean cages without food at 9am. Water was provided ad libitum. All mice were euthanized between noon and 4 pm by CO2 overexposure in no particular order with respect to gender or phenotype. Mouse aortas were dissected and fixed in Prefer fixative. The extent of atherosclerosis (Phase 3 Imaging Systems, Glen Mills, PA) was determined by the en face methods and by assessment of aortic root lesion burden, as described previously14.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Prostanoids

Urinary prostanoid metabolites were measured by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry as described15. Such measurements provide a noninvasive, time integrated measurement of systemic prostanoid biosynthesis16. Briefly, mouse urine samples were collected using metabolic cages over a 8 hour period (9am to 5pm). Systemic production of PGI2, PGE2, PGD2, and TxA2 was determined by quantifying their major urinary metabolites - 2, 3-dinor 6-keto PGF1α (PGIM), 7-hydroxy-5, 11-diketotetranorprostane-1, 16-dioic acid (PGEM), 11, 15-dioxo-9α-hydroxy-2, 3, 4, 5-tetranorprostan-1, 20-dioic acid (tetranor PGDM) and 2, 3-dinor TxB2 (TxM), respectively. Results were normalized with creatinine.

Immunohistochemical Examination of Lesion Morphology

Mouse hearts were embedded in OCT, and 10 μm serial sections of the aortic root were cut and mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific) for analysis of lesion morphology. Samples were fixed in acetone for 15 min at −20°C. Prior to treatment with the first antibody, sections were consecutively treated to block endogenous peroxidase (3% H2O2 for 15 min), with 10% normal serum blocking solution (dependent on host of secondary antibody, in 1%BSA/PBS for 15 min) and for endogenous biotin (streptavidin-biotin blocking kit, #SP-2002, Vector Laboratories). Sections were then incubated with the desired primary antibody in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Samples were individually stained for collagen type-I (1 μg/ml, #1310-01, Southern Biotech), α-SMA (12.3 μg/ml, #F3777, Sigma), VCAM-1 (5 μg/ml, #553331, BD Bioscience) and CD11b (2.5 μg/ml, #557395, BD Bioscience), all with isotype-matched controls. Where required, sections were then incubated with biotinylated-IgG secondary antibody (specific to host of primary antibody, all 1 μg/ml, Vector Laboratories) diluted in 1%BSA/PBS for 1 hr at RT. Sections were then incubated with Streptavidin-Horseradish Peroxidase (1 μg/ml, #016-030-084, Jackson Immunoresearch) diluted in 1%BSA/PBS for 30 min at RT. Slides were equilibrated in sterile H2O for 5 min at RT, then developed using the DAB substrate kit (#K3468, Dako) as per manufacturers’ protocol. Samples were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted in Cytoseal-60 (#12-547, Fisher Scientific). Isotype-match controls were performed in parallel and showed negligible staining in all cases.

Statistical Analysis

All animals were the same age and on the same LdIR KO background. For most analyses separate conclusions are drawn for males and females, and separate conclusions are drawn for animals sacrificed at 3 and 6 months on the HFD. Therefore separate statistical analyses were performed for these cases. Where conclusions involve multiple factors, two-way ANOVA was used. Repeated measures ANOVA was used where appropriate. Post-hoc testing was performed using the Holm-Sidak’s test. A significance threshold of 0.05 was used. Significance of greater than 0.01 is indicated by double-asterisks on the graphs and significance greater than 0.001 is indicated by triple-asterisks. Sample sizes were based on variability of the test measurement and the desire to detect a minimal 10% difference in the variables assessed with α = 0.05 and the power (1−β) = 0.8.

Results

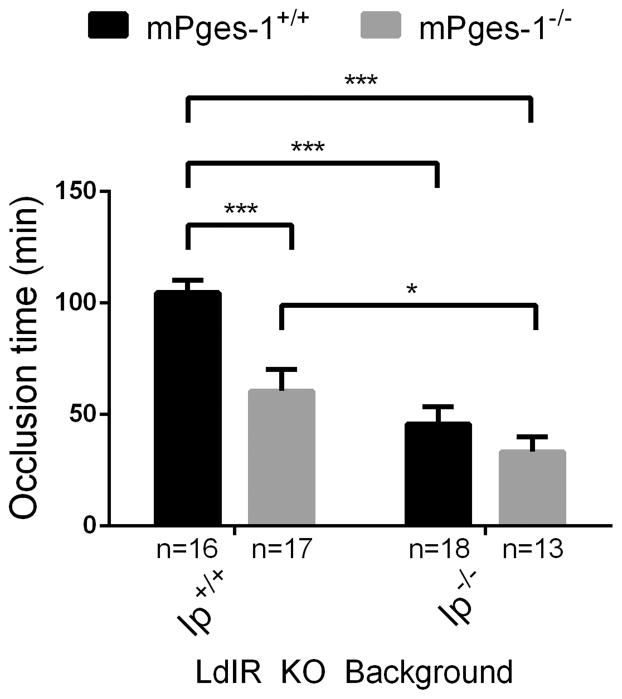

Deletion of the Ip in mPges-1-deficient hyperlipidemic mice promotes thrombogenesis

The time to thrombotic carotid artery occlusion after photochemical injury was accelerated in female mPges-1 KOs (60.62 ± 9.7 min); further augmentation of thrombogenesis was evident in Ip KOs (45.72 ± 7.7 min), and the phenotype was most pronounced in compound mutant mice (27.29 ± 3.1 min) when compared to LdlR KOs (104.7 ± 5.6 min) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Deletion of prostacyclin receptor (Ip) in microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (mPges-1)-deficient hyperlipidemic mice promote thrombogenesis.

The time to thrombotic carotid artery occlusion after photochemical injury was accelerated in Ip and mPges-1KOs and in compound mutants. Two-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of genotypes on occlusion time in female mice aged 3–4 months (Ip- p< 0.0001, mPges-1- p= 0.0005, interaction- p= 0.0455). Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison tests were used to test significant differences between LdlR KO and different mutants. Data are expressed as means ± SEMs. *p< 0.05, ***p<0.001, n=13–18 per genotype.

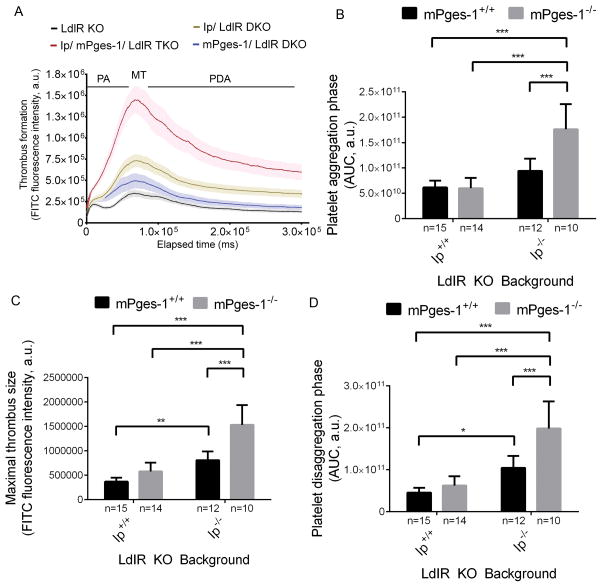

For male mice, thrombogenesis was monitored in real-time after laser-induced injury in cremaster arterioles. As in the carotid artery, deletion of mPges-1 modestly increased thrombogenesis compared to LdlR KOs (Figure 2A). However, no significant differences in the area under the median integrated fluorescence intensity/ time curve (AUC) were detected for platelet aggregation and disaggregation phases and maximal thrombus size (Figure 2B–2D). Ip depletion alone significantly increased maximal thrombus size and the AUC of the platelet disaggregation phase compared to LdlR KOs. Thrombogenesis was markedly further augmented by coincident deletion of the Ip and mPges-1 (Figure 2A). Here, the AUC of the platelet aggregation and disaggregation phases and maximal thrombus size were all significantly increased compared to single and double KO mutants (Figure 2B–2D).

Figure 2. PGI2 restrains thrombogenesis in hyperlipidemic mice.

Thrombogenesis in cremaster arterioles after laser-induced injury in LdlR KO, Ip/ LdlR DKO, mPges-1/ LdlR DKO, and Ip/mPges-1/ LdlR TKO male mice (A). Thrombus formation was visualized in real-time with fluorescently labeled platelets as described in the Methods. Median integrated fluorescence intensity of platelets representing thrombus formation was plotted versus time after laser-induced injury of the cremaster arteriole vessel wall. Fluorescence intensity from 15–20 thrombi was averaged from each mouse. Data correspond to platelet aggregation phase (B), maximal thrombus size (C) and platelet disaggregation phase (D) were extracted from the fluorescence-time curves and averaged. Two-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of genotypes on thrombus formation in male mice aged 3–4 months (B, Ip- p< 0.0001, mPges-1- p= 0.0015, interaction- p= 0.0010; C, Ip- p< 0.0001, mPges-1- p <0.0001, interaction- p= 0.0010; D, Ip- p< 0.0001, mPges-1- p= 0.0003, interaction- p= 0.010). Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison tests were used to test significant differences between LdlR KO and different mutants. Data are expressed as means ± SEMs. *p< 0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; n=10–15 per genotype. PA- platelet aggregation; MT- maximal thrombus; PDA- platelet disaggregation.

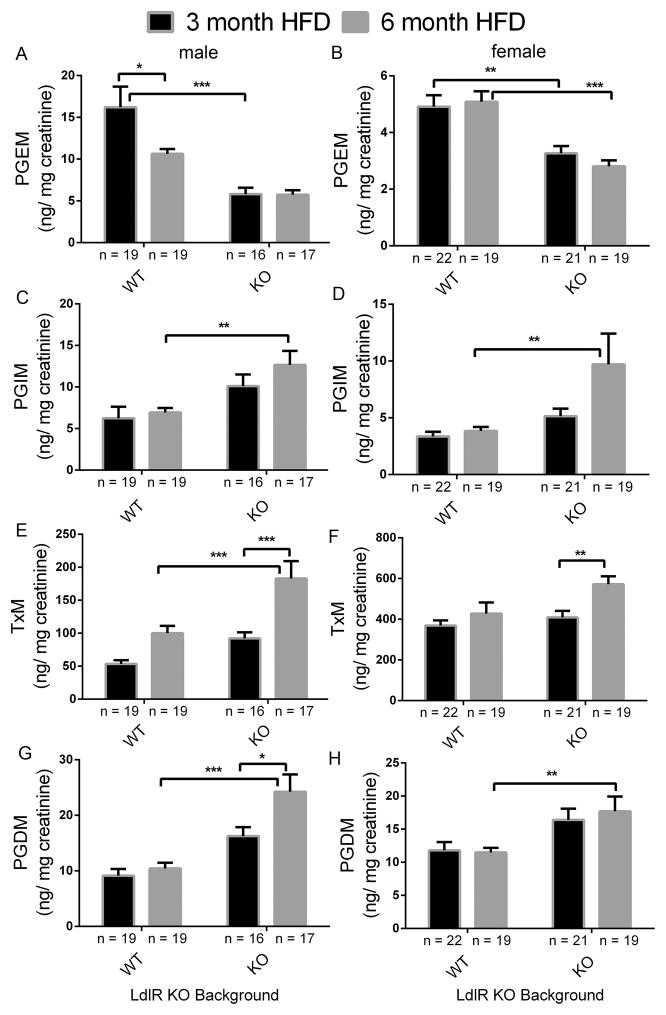

Impact of Ip and mPges-1 deletion on prostaglandin biosynthesis in mice on a high-fat diet (HFD)

Deletion of the Ip together with mPges-1 in hyperlipidemic mice suppressed PGE2 but increased PGI2 biosynthesis as reflected by urinary PGEM (7-hydroxy-5, 11-diketotetranorprostane-1, 16-dioic acid) and PGIM (2, 3-dinor 6-keto PGF1α) respectively (Suppl. Figure 1A and 1B). Urinary PGIM increased further when mice were fed a HFD diet for 3 or 6 months in both sexes (Figure 3A, 3B), while PGEM remained unaltered (Figure 3C, 3D). Biosynthesis of Tx, as reflected by urinary 2, 3-dinor TxB2 (TxM) also increased in the LdlR KOs fed a high fat diet and this was more pronounced in the TKOs (Figure 3E, 3F). PGDM (11, 15-dioxo-9α-hydroxy-2, 3, 4, 5-tetranorprostan-1, 20-dioic acid) levels were not changed in female mice (Figure 3H). However, in male mice, PGDM levels were augmented in the TKO mutants at baseline (Suppl. Figure 1D). After feeding a HFD, PGDM levels were elevated in the TKOs compared to WTs (Figure 3G and 3H).

Figure 3. Impact of prostacyclin receptor (Ip) and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (mPges-1) deletion on prostaglandin biosynthesis in mice on a high-fat diet (HFD).

Fasting (9am-5 pm) urine samples from LdlR KO (WT) and Ip/mPges-1/ LdlR TKO (KO) mice were collected at the end of a HFD feeding, and prostanoids metabolites were analyzed by liquid chromatography/ mass spectrometry, as described in the Methods. Deletion of Ip and mPges-1 suppressed PGE2 but increased PGI2 biosynthesis as reflected in their urinary PGEM (7-hydroxy-5, 11-diketotetranorprostane-1, 16-dioic acid) (A and B) and PGIM (2, 3-dinor 6-keto PGF1α) (C and D) metabolites, respectively. Urinary 2, 3-dinor TxB2 (TxM) was also elevated in LdlR KO and TKO mutants after feeding a HFD in both sexes (E and F). PGDM (11, 15-dioxo-9α-hydroxy-2,3,4,5-tetranorprostan-1,20-dioic acid) levels in mice were augmented in the TKO mutants (G and H). PGDM levels in female were not changed between WT and KOs. Two-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of genotype and/ or treatment on urinary prostanoid levels in both genders fed a HFD (PGEM, male- genotype, p< 0.0001, treatment, p= 0.0538, interaction, p= 0.0591; PGEM, female- genotype, p< 0.0001, treatment, p= 0.6640, interaction, p= 0.3409; PGIM, male- genotype, p= 0.0005, treatment, p= 0.2168, interaction, p= 0.4786; PGIM, female- genotype, p= 0.0057, treatment, p= 0.0643, interaction, p= 0.1341; TxM, male- genotype, p= 0.0001, treatment, p< 0.0001, interaction, p= 0.1423; TxM, female- genotype, p= 0.0220, treatment, p= 0.0062, interaction, p= 0.1866; PGDM, male- genotype, p< 0.0001, treatment, p= 0.0153, interaction, p= 0.0781; PGDM, female- genotype, p= 0.0006, treatment, p= 0.7456, interaction, p= 0.6011). Multiple comparison tests (Holm-Sidak) were used to test significant differences between LdlR KO and Ip/mPges-1/ LdlR TKOs. Data are expressed as means ± SEMs. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001; n=16–19 (male) and 19–22 (female) per genotype.

A significant gender difference was observed at baseline in PGEM (female vs male- 4.87 ± 0.4 vs 23.44 ± 1.5 ng/ mg creatinine,), TxM (female vs male- 170.7 ± 9.7 vs 60.42 ± 7.7 ng/ mg creatinine,) and PGDM (female vs male- 12.45 ± 1.3 vs 21.36 ± 2.5 ng/ mg creatinine,) in LdlR KOs (WT), but not in PGIM (female vs male- 2.28 ± 0.1 vs 2.75 ± 0.3 ng/ mg creatinine,).

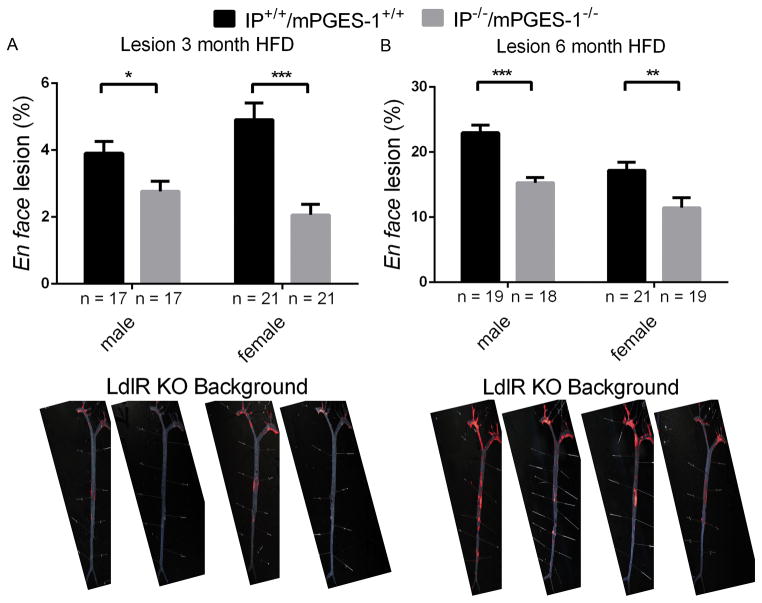

Combined Ip and mPges-1 deletion restrains atherogenesis

All mice gained weight after feeding a HFD for 3 or 6 months. However, there were no significant differences between LdlR KO and TKOs (Suppl. Figure 2A–2D). Combined deletion of the Ip and mPges-1 did not affect systolic blood pressure (SBP) in either female and male mice at baseline and SBP remained unaltered between LdlR KOs when compared to TKOs as they developed atherosclerosis (Suppl. Figure 3A–3C). The heart rate of mice was unaltered between Ldl-receptor KOs and TKOs (Suppl. Figure 3D–3F). There were no significant effects of genotype on fasting plasma glucose and triglyceride levels at all time points of mice on a HFD (Suppl. Figure 4A–4D).

Aortic atherosclerotic lesion development was significantly delayed in both sexes by combined deletion of the Ip and mPges-1 in LdlR KOs at 3 and 6 months on a HFD (Figure 4A-3 months HFD, female, 2.06 ± 0.3% vs 4.91± 0.5%; male, 2.77 ± 0.3% vs 3.91 ± 0.4%) and (Figure 4B-6 months HFD, female, 11.46 ± 1.5% vs 17.20 ± 1.3%; male, 15.28 ± 0.8% vs 22.99 ± 1.2%). Representative en face preparations are shown (Figure 4, lower panels).

Figure 4. Prostacyclin receptor (Ip) and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (mPges-1) deletion restrains atherogenesis.

Aortic atherosclerotic lesion burden, represented by the percentage of lesion area to total aortic area, was quantified by en face analysis of aortas from mice of both sexes fed a HFD for 3 or 6 months. Representative en face preparations are shown (Lower panels). Lesion area was decreased in both male and female of TKO mutants fed a HFD for 3 or 6 months (A-3 month HFD and B-6 month HFD). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant decrease in lesion area of Ip/mPges-1/ LdlR TKOs compared with LdlR KOs (3 month HFD- genotype, p< 0.0001, gender, p= 0.7010, interaction, p= 0.0304; 6 month HFD- genotype, p< 0.0001, gender, p= 0.0002, interaction, p= 0.4330). Data are expressed as means ± SEMs. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001; n=17–21 per genotype.

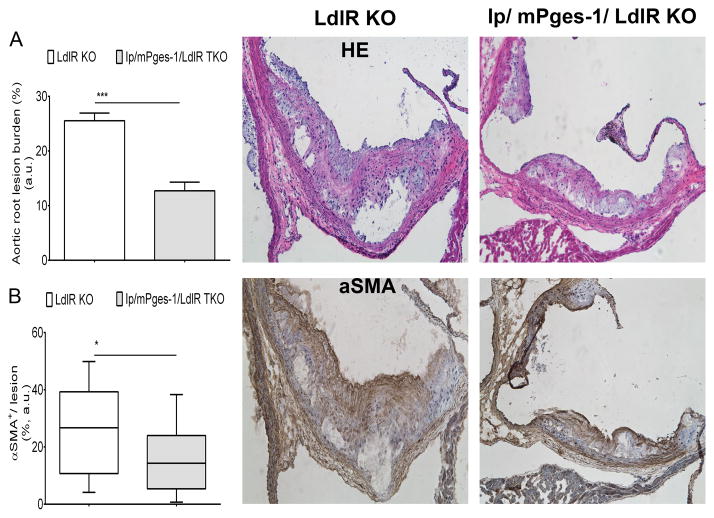

Lesional Morphology Consequent to Ip/ mPges-1 Deletion in Male Mice

Consistent with the results for atherosclerotic lesion burden analyzed by en face staining of aortas, cross-sectional analysis of aortic root samples in male mice fed a HFD for 3 months revealed smaller lesions in Ip/ mPges-1/ LdlR TKOs compared to LDLR-KO (Figure 5). Morphological analysis by immunohistochemistry showed a significant decrease in αSMA staining (Figure 5) in lesions from Ip/mPges-1/LdlR TKO animals. This suggested that these smaller lesions were less-advanced, containing less αSMA-positive de-differentiated and re-differentiated smooth-muscle cells. Furthermore, staining for VCAM-1 (Suppl. Figure 5A) and type-I collagen both showed a trend towards lower content in lesions from the triple-KO mice. CD11b staining for macrophages showed no difference between the two genotypes, nor did lesional necrotic cores (Suppl. Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Morphometric consequences of prostacyclin receptor (Ip) and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (mPges-1) deletion on lesion development.

A. Quantification of cross-sectional analysis of aortic root samples from male mice fed a 3-month high-fat diet was performed by measuring total lesion area across the aortic root, as described in methods. A parametric t-test (2-tailed) revealed a significant effect of genotype on lesion progression. Data are expressed as means ± SEMs. *p< 0.05, ***p< 0.001, n=7 per genotype (21 lesions).

Discussion

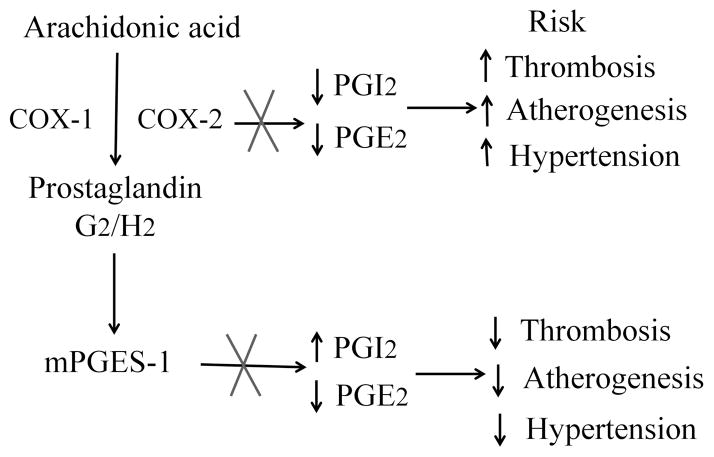

NSAIDs have conferred a cardiovascular hazard, including a spectrum of myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure and hypertension17, that is attributable to suppression of COX-2 derived cardioprotective prostaglandins, such as PGI218. This hazard has been definitively established by placebo controlled trials for NSAIDs designed to inhibit specifically COX-2, but indirect evidence also implicates older NSAIDs such as diclofenac, that are also selective COX-2 inhibitors18–20. Concern about the cardiovascular hazard from NSAIDs has prompted interest in alternative drug targets, including mPGES-1. This enzyme, downstream of the COXs, is the dominant source of PGE2, as reflected by marked suppression of urinary PGEM with gene deletion in mice4 or enzyme inhibition in humans21. In both cases, accumulation of the PGH2 substrate for mPGES-1 enables its rediversion to other PG synthases, the products of which vary by cell type9, 22, 23. Thus, in contrast to inhibition or either global or vascular deletion COX-2 which depresses PGI2 and predisposes to thrombosis, atherogenesis and hypertension in mice 4, 24, 25, global or vascular deletion of mPges-1 augments PGI2, restrains atherogenesis and the response to vascular injury and does not accelerate thrombogenesis 4, 8, 12, 23 (Figure 6). Although the distinction is not absolute and is likely conditioned by genetic background9, deletion of mPges-1 is also less likely to augment hypertension evoked by a high salt diet than is deletion of COX-24, 23.

Figure 6. Simplified schema for the cardiovascular consequences of COX-2 versus mPGES-1 inhibition.

Inhibition of COX-2 predisposes mice to thrombosis, atherogenesis and hypertension, attributable to suppression of PGI2 and PGE2 biosynthesis. Deletion of mPges-1 results in rediversion of accumulated PGH2 substrate to prostacyclin synthase, augmenting PGI2 while suppressing PGE2 biosynthesis. This shift in substrate to PGI2 restrains thrombosis, hypertension and atherogenesis. X- Inhibition or deletion of enzyme.

Here, we wished to address the relative contribution of suppressing PGE2 vs augmenting PGI2 to the impact of mPges-1 deletion on thrombogenesis and atherogenesis in mice. We wished to do this on a hyperlipidemic background to simulate more faithfully the atherosclerosis likely extant in the patient population targeted for chronic analgesia from mPGES-1 inhibitors. Furthermore, we have previously reported that biosynthesis of both PGI2 and TxA2 increase as hyperlipidemic mice develop atherosclerosis on a high fat diet26, presumably reflective of accelerated platelet- vessel wall interactions26, 27 and that the major rediversion product of mPges-1 deletion in macrophages is TxA222, 23. Thus, while mPges-1 deletion does not augment thrombogenesis in normolipidemic mice, a changing pattern of substrate rediversion might modulate the consequence of its depletion on a LdlR deficient background.

PGE2 can directly modulate thrombosis in mouse models. Lower concentrations activate platelets in vitro via the E prostanoid receptor 3 (EP3)28 and deletion of EP3 restrains thrombogenesis in vivo29. Higher concentrations of PGE2 inhibit platelet aggregation in vitro via activation of the IP30. Here we show that mPges-1 depletion modestly accelerates thrombogenesis consequent to both macrovascular and microvascular injury in LdlR KOs. As expected4, deletion of the Ip augments thrombosis to a greater extent in both models. However, concomitant deletion of the Ip markedly augments macro and microvascular thrombosis in hyperlipidemic, mPges-1 depleted mice. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that substrate diversion to PGI2, rather than suppression of PGE2 mediated activation of EP3, represents the dominant mechanism by which mPges-1 deletion restrains thrombogenesis.

Our studies with atherogenesis suggest a different mechanism for the beneficial effects of mPges-1 deletion, even though deletion of the Ip alone fosters initiation and early acceleration of atherogenesis5, 31. Here, we have previously reported that mPges-1 deletion in LdlR KO mice restrains atherogenesis8. If this was reflective of substrate rediversion to PGI2, combined deletion with the Ip would be expected to abrogate this effect. Here we show that in these mice PGE2 is suppressed and biosynthesis of PGI2 is augmented, as expected. However, despite deletion of the Ip, restraint of atherogenesis is conserved, attributing the phenotype predominantly to suppression of PGE2, likely acting via its EP2 and EP4 receptors32, 33. Interestingly, biosynthesis of Tx increased with progression on the high fat diet in the absence of the restraining effect of PGI2. However, despite this, the anti-atherogenic consequence of mPges-1 deletion was retained. Deletion of Ip and mPges-1 restrains the development of lesions as revealed by en face staining of aortas and cross-sectional analysis of the aortic root. Morphological analyses also supported this finding, as shown by decreased αSMA staining in lesions in TKO mice. In order to determine if these early changes caused by Ip and mPges-1 deletion lead to gross morphological changes in advanced lesions, it would be beneficial to examine the morphology of equally- sized lesions across the two groups (e.g 3-month HFD LdlR-KO versus 6-month HFD triple-KO).

Hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease associated with NSAIDs selective for inhibition for COX-218. Although we have previously reported that deletion of mPges-1 had no effect on SBP in LdlR KO mice fed a HFD for 6 months8, others have reported variable effects on blood pressure34, 35. Suppression of COX-2 derived vascular PGI24 and renal and dermal PGE2 results in hypertension in mice fed a high salt diet as does deletion of either the Ip36, 37 or Ep238. Here, using tail cuff measurements, we did not observe an alteration in systolic blood pressure consequent to deletion of mPges-1 alone or in combination with the Ip in LdlR KO mice. Indeed, the SBP of female TKOs at 6 months was lower than in LdlR KO littermates. A more comprehensive study, using telemetry and evocation of hypertension, such as with a high salt diet, is necessary to address comprehensively how differential effects on E and I prostanoids might modulate blood pressure in the absence of mPGES-1.

In summary, deletion of mPges-1 appears to restrain thrombogenesis by augmenting PGI2 dependent activation of the IP. By contrast, it restrains atherogenesis predominantly by suppressing PGE2. Both properties are retained in genetically prone hyperlipidemic mice despite a progressive increase in biosynthesis of Tx alongside PGI2 during administration of a high fat diet. Thus, a divergent impact on biosynthesis of PGI2 would suggest that mPGES-1 inhibitors will be less prone to thrombotic complications than NSAIDs.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

Inhibition of mPGES-1 both suppresses PGE2 and results in substrate rediversion to enhance PGI2. Here we show the former effect accounts for the restraint on atherogenesis of mPGES-1 deletion while augmented PGI2 limits evoked thrombogenesis. Suppression of PGI2 is the dominant mechanism by which NSAIDs promote thrombosis and atherogenesis.

What are the clinical implications?

The adverse cardiovascular hazard associated with NSAIDs and the addictive properties of opioids have emphasized the need for new analgesics. Inhibitors of mPGES-1 are in early clinical development.

Experiments in mice suggest comparable analgesic efficacy but enhanced cardiovascular safety compared to NSAIDs. Here two mechanisms by which the latter happens are elucidated.

Urinary PGIM may be useful as a discriminant biomarker of cardiovascular risk between NSAIDs and mPGES-1 inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical support and advice of Weili Yan, Helen Zou, and Wenxuan Li-Feng.

Sources of Funding

Supported by a grant (HL062250) from the National Institutes of Health. GAF is the McNeil Professor of Translational Medicine and Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Samuelsson B, Morgenstern R, Jakobsson PJ. Membrane prostaglandin e synthase-1: A novel therapeutic target. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:207–224. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koeberle A, Werz O. Perspective of microsomal prostaglandin e2 synthase-1 as drug target in inflammation-related disorders. Biochemical pharmacology. 2015;98:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakobsson PJ, Thoren S, Morgenstern R, Samuelsson B. Identification of human prostaglandin e synthase: A microsomal, glutathione-dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng Y, Wang M, Yu Y, Lawson J, Funk CD, FitzGerald GA. Cyclooxygenases, microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1, and cardiovascular function. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1391–1399. doi: 10.1172/JCI27540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan KM, Lawson JA, Fries S, Koller B, Rader DJ, Smyth EM, FitzGerald GA. Cox-2-derived prostacyclin confers atheroprotection on female mice. Science. 2004;306:1954–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trebino CE, Stock JL, Gibbons CP, Naiman BM, Wachtmann TS, Umland JP, Pandher K, Lapointe JM, Saha S, Roach ML, Carter D, Thomas NA, Durtschi BA, McNeish JD, Hambor JE, Jakobsson PJ, Carty TJ, Perez JR, Audoly LP. Impaired inflammatory and pain responses in mice lacking an inducible prostaglandin e synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9044–9049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332766100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamei D, Yamakawa K, Takegoshi Y, Mikami-Nakanishi M, Nakatani Y, Oh-Ishi S, Yasui H, Azuma Y, Hirasawa N, Ohuchi K, Kawaguchi H, Ishikawa Y, Ishii T, Uematsu S, Akira S, Murakami M, Kudo I. Reduced pain hypersensitivity and inflammation in mice lacking microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33684–33695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M, Zukas AM, Hui Y, Ricciotti E, Pure E, FitzGerald GA. Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1 augments prostacyclin and retards atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14507–14512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606586103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang M, FitzGerald GA. Cardiovascular biology of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2010;20:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda-Matsuo Y, Ota A, Fukada T, Uematsu S, Akira S, Sasaki Y. Microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1 is a critical factor of stroke-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11790–11795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604400103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M, Lee E, Song W, Ricciotti E, Rader DJ, Lawson JA, Pure E, FitzGerald GA. Microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1 deletion suppresses oxidative stress and angiotensin ii-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circulation. 2008;117:1302–1309. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.731398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, Ihida-Stansbury K, Kothapalli D, Tamby MC, Yu Z, Chen L, Grant G, Cheng Y, Lawson JA, Assoian RK, Jones PL, FitzGerald GA. Microsomal prostaglandin e2 synthase-1 modulates the response to vascular injury. Circulation. 2011;123:631–639. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.973685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Y, Ricciotti E, Scalia R, Tang SY, Grant G, Yu Z, Landesberg G, Crichton I, Wu W, Pure E, Funk CD, FitzGerald GA. Vascular cox-2 modulates blood pressure and thrombosis in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:132ra154. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tangirala RK, Rubin EM, Palinski W. Quantitation of atherosclerosis in murine models: Correlation between lesions in the aortic origin and in the entire aorta, and differences in the extent of lesions between sexes in ldl receptor-deficient and apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:2320–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song WL, Lawson JA, Wang M, Zou H, FitzGerald GA. Noninvasive assessment of the role of cyclooxygenases in cardiovascular health: A detailed hplc/ms/ms method. Methods Enzymol. 2007;433:51–72. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)33003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FitzGerald GA, Pedersen AK, Patrono C. Analysis of prostacyclin and thromboxane biosynthesis in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1983;67:1174–1177. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.6.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.FitzGerald GA. Cox-2 in play at the aha and the fda. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosser T, Yu Y, FitzGerald GA. Emotion recollected in tranquility: Lessons learned from the cox-2 saga. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:17–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-011209-153129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Tacconelli S, Patrignani P. Role of dose potency in the prediction of risk of myocardial infarction associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1628–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grosser T, Fries S, FitzGerald GA. Biological basis for the cardiovascular consequences of cox-2 inhibition: Therapeutic challenges and opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:4–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI27291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seyberth HW, Sweetman BJ, Frolich JC, Oates JA. Quantifications of the major urinary metabolite of the e prostaglandins by mass spectrometry: Evaluation of the method’s application to clinical studies. Prostaglandins. 1976;11:381–397. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trebino CE, Eskra JD, Wachtmann TS, Perez JR, Carty TJ, Audoly LP. Redirection of eicosanoid metabolism in mpges-1-deficient macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16579–16585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Yang G, Xu X, Grant G, Lawson JA, Bohlooly YM, FitzGerald GA. Cell selective cardiovascular biology of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1. Circulation. 2013;127:233–243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.119479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu Z, Crichton I, Tang SY, Hui Y, Ricciotti E, Levin MD, Lawson JA, Pure E, FitzGerald GA. Disruption of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway attenuates atherogenesis consequent to cox-2 deletion in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6727–6732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115313109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang SY, Monslow J, Todd L, Lawson J, Pure E, FitzGerald GA. Cyclooxygenase-2 in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells restrains atherogenesis in hyperlipidemic mice. Circulation. 2014;129:1761–1769. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pratico D, Cyrus T, Li H, FitzGerald GA. Endogenous biosynthesis of thromboxane and prostacyclin in 2 distinct murine models of atherosclerosis. Blood. 2000;96:3823–3826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.FitzGerald GA, Smith B, Pedersen AK, Brash AR. Increased prostacyclin biosynthesis in patients with severe atherosclerosis and platelet activation. The New England journal of medicine. 1984;310:1065–1068. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404263101701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabre JE, Nguyen M, Athirakul K, Coggins K, McNeish JD, Austin S, Parise LK, FitzGerald GA, Coffman TM, Koller BH. Activation of the murine ep3 receptor for pge2 inhibits camp production and promotes platelet aggregation. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:603–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gross S, Tilly P, Hentsch D, Vonesch JL, Fabre JE. Vascular wall-produced prostaglandin e2 exacerbates arterial thrombosis and atherothrombosis through platelet ep3 receptors. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:311–320. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shio H, Ramwell P. Effect of prostaglandin e 2 and aspirin on the secondary aggregation of human platelets. Nature: New biology. 1972;236:45–46. doi: 10.1038/newbio236045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi T, Tahara Y, Matsumoto M, Iguchi M, Sano H, Murayama T, Arai H, Oida H, Yurugi-Kobayashi T, Yamashita JK, Katagiri H, Majima M, Yokode M, Kita T, Narumiya S. Roles of thromboxane a(2) and prostacyclin in the development of atherosclerosis in apoe-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:784–794. doi: 10.1172/JCI21446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuriyama S, Kashiwagi H, Yuhki K, Kojima F, Yamada T, Fujino T, Hara A, Takayama K, Maruyama T, Yoshida A, Narumiya S, Ushikubi F. Selective activation of the prostaglandin e2 receptor subtype ep2 or ep4 leads to inhibition of platelet aggregation. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2010;104:796–803. doi: 10.1160/TH10-01-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cipollone F, Fazia ML, Iezzi A, Cuccurullo C, De Cesare D, Ucchino S, Spigonardo F, Marchetti A, Buttitta F, Paloscia L, Mascellanti M, Cuccurullo F, Mezzetti A. Association between prostaglandin e receptor subtype ep4 overexpression and unstable phenotype in atherosclerotic plaques in human. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2005;25:1925–1931. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000177814.41505.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Facemire CS, Griffiths R, Audoly LP, Koller BH, Coffman TM. The impact of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase 1 on blood pressure is determined by genetic background. Hypertension. 2010;55:531–538. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jia Z, Zhang A, Zhang H, Dong Z, Yang T. Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1 increases sensitivity to salt loading and angiotensin ii infusion. Circ Res. 2006;99:1243–1251. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000251306.40546.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Francois H, Athirakul K, Howell D, Dash R, Mao L, Kim HS, Rockman HA, FitzGerald GA, Koller BH, Coffman TM. Prostacyclin protects against elevated blood pressure and cardiac fibrosis. Cell metabolism. 2005;2:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe H, Katoh T, Eiro M, Iwamoto M, Ushikubi F, Narumiya S, Watanabe T. Effects of salt loading on blood pressure in mice lacking the prostanoid receptor gene. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2005;69:124–126. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kennedy CR, Zhang Y, Brandon S, Guan Y, Coffee K, Funk CD, Magnuson MA, Oates JA, Breyer MD, Breyer RM. Salt-sensitive hypertension and reduced fertility in mice lacking the prostaglandin ep2 receptor. Nat Med. 1999;5:217–220. doi: 10.1038/5583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.