Abstract

Functional strength training is becoming increasingly popular when rehabilitating individuals with neurological injury such as stroke or cerebral palsy. Typically, resistance during walking is provided using cable robots or weights that are secured to the distal shank of the subject. However, there exists no device that is wearable and capable of providing resistance across the joint, allowing over ground gait training. In this study, we created a lightweight and wearable device using eddy current braking to provide resistance to the knee. We then validated the device by having subjects wear it during a walking task through varying resistance levels. Electromyography and kinematics were collected to assess the biomechanical effects of the device on the wearer. We found that eddy current braking provided resistance levels suitable for functional strength training of leg muscles in a package that is both lightweight and wearable. Applying resistive forces at the knee joint during gait resulted in significant increases in muscle activation of many of the muscles tested. A brief period of training also resulted in significant aftereffects once the resistance was removed. These results support the feasibility of the device for functional strength training during gait. Future research is warranted to test the clinical potential of the device in an injured population.

Keywords: Exoskeleton, EMG, Gait Training, Interface, Muscle Strength, Rehabilitation, Robotics

Introduction

Many patients with stroke, cerebral palsy, and other neurological conditions have significant limitations in walking, and experience limited mobility for the rest of their life.11, 15, 45 Lack of mobility significantly affects functional independence, and consequently results in greater physical disability.20 Facilitating gait recovery, therefore, is a key goal in rehabilitation. With the growing elderly population, the prevalence of many of the neurological conditions is expected to increase worldwide, and the need for interventions to address gait dysfunction will grow.36 Appropriately designed rehabilitation devices can assist in meeting this imminent heightened demand for care.

Task-specific training is recognized as the preferred method for gait training following neurological injury because the motor activity seen in this type of rehabilitation is known to facilitate neural plasticity and functional recovery.13, 25, 35 However, current task-oriented gait training approaches seldom focus on improving muscle strength and impairment, which are also critical for motor recovery and plasticity.10, 30, 34 For example, incorporating strengthening exercises into rehabilitation interventions can counteract muscle weakness and improve function in individuals with a wide variety of neuromuscular disorders.31, 33, 41 Numerous studies have also demonstrated a link between the ability to produce adequate force in the muscles of lower limbs and gait speed following neurological injury.11, 21 Additionally, resistance training may result in adaptive changes in the central nervous system.5 However, the benefits of strength training may not translate maximally into improvements in gait function unless the training incorporates task-specific elements.17 This task-specific loading of the limbs–termed as functional strength training–is gaining popularity when rehabilitating individuals with neurological injury.29, 50

Devices do exist to provide functional strength training during walking. The simplest of which applies resistance by placing a weight on the lower limb. Research indicates that this intervention can increase the metabolic rate of healthy subjects4 as well as increase power of the hip and knee, and muscle activation during walking in neurologically injured populations.14 While this method of functional strength training is simple and practicable, it is hindered by a low torque-to-weight ratio: making large resistances unobtainable without excessively large weights. Cable driven devices, such as that created by Wu et al,48 address this issue by locating the heavy force generating elements (actuators and cable spools) away from the patient. This device resists ankle translation during the swing phase of gait, and studies have found that it can potentially improve step length symmetry51 and gait speed following stroke.49 However, methods that resist the user through cables will be difficult to use in over-ground training.

The majority of the existing methods for functional strength training apply resistance to the end effector region of the leg (i.e., foot or ankle). Because of this, the resistance may be irregularly distributed between the hip and knee joints, and compensatory strategies could be promoted as weaker muscles are not specifically targeted in the training. The magnitude of resistance applied to the leg could also change as a function of limb position. Further, the resistance in these applications is usually unidirectional, which would assist movement during certain phases of gait. Bidirectional resistance is possible, but only obtainable with supplementary equipment (additional actuators and cables) and controls that utilize gait detection. For these reasons, providing resistance in the joint space (i.e., across the joint) may be beneficial for training and other biomechanical evaluations. However, making a device that is lightweight and wearable while still providing high bidirectional torque requires a unique approach. Therefore, the goal of this study was to develop a gait-training device that is capable of providing variable levels of resistance across the knee during walking and to test the biomechanical effects of this device on the wearer by studying muscle activation patterns and sagittal plane kinematics during treadmill walking.

Materials and Methods

This study consisted of two phases: (1) development of a lightweight wearable device that provides resistance to the leg during walking and (2) evaluation of the effects of that device in a study involving healthy human subjects.

Eddy Current Braking for Functional Strength Training

A device was created with the goal of providing resistance across the joint during concentric flexion and extension of the knee. In order to accomplish this, we created a benchtop viscous damping device in the form of an eddy current disc brake, and later adapted it for a commercially available knee brace (T Scope Premier Post-Op Knee Brace, Breg, Grand Prairie, TX). Eddy current brakes convert kinetic energy into electrical currents with the motion of a conductor through a magnetic field. Eddy currents, which are localized circular electric currents within the conductor, slow or stop a moving object by dissipating kinetic energy as heat, thus providing a non-contact dissipative force that is proportional and opposite to the velocity of the movement (Fig. 1a). Eddy current braking has been widely used in applications such as trains, roller-coasters, and even some exercise equipment (i.e., stationary bikes); however, to the authors’ knowledge, it has not been miniaturized and made wearable for rehabilitation purposes. We selected this method of resistance because it provides a smooth, contact free, and frictionless means of generating loads applied directly to the knee that can further be engineered into a compact and lightweight device.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Diagram showing the basis of force generation during eddy current braking. As the disc rotates through a magnetic field (B) with angular velocity (ω), eddy currents (I) form within the disc. In accordance with Lorentz force equation and the right hand rule, the resulting force always opposes the angular velocity. (b) Principles that affect the magnitude of the torque experienced during braking based on equation (1). (c) Experimental set-up of benchtop testing.

The most widely studied configuration of eddy current braking is that of a rotational disc. Previous research performed over the past several decades has determined many of the parameters that govern the phenomenon.43, 47 This work was elegantly summarized by Gosline and Hayward19 for eddy current braking as it applies to haptic devices (1).

| (1) |

In this equation, resistive torque t depends on the conductivity of the disc material σ, area of the disc exposed to the magnetic field A, the thickness of the disc d, the magnitude of the magnetic field strength B, the effective radius of the disc R, and the angular velocity of the disc rotation ω, as shown in Fig. 1b. This means that simply changing the area of the aluminum disc exposed to the magnetic field can change the resistive properties of the device.

In the design of our benchtop device, two pairs of permanent magnets (DX08B-N52, KJ Magnetics, Pipersville, Pa) mounted on a ferromagnetic backiron were used to create the magnetic field. Eddy currents were induced within a non-ferrous, 10.16 cm (4 in) diameter aluminum disc (6061 aluminum alloy). Aluminum was chosen as the disc material because it is both lightweight and conductive. The disc was also interchangeable, which allowed us to test the effect of disc thickness (1 mm, 3 mm, and 5 mm) on the resistive torque generated by the device. The device was outfitted with a gearbox (227 g, 2 stage, planetary) (P60, BaneBots, Loveland, CO) with a 26:1 ratio in order to amplify angular velocity of the disc as well as the torque applied to the leg.

The benchtop device was then characterized for its resistive torque profile using an isokinetic dynamometer (System Pro 4, Biodex, Shirley, NY). A custom built jig was used to rigidly attach the device to the input arms of the dynamometer (Fig. 1c). Care was taken to ensure that the axis of the dynamometer was aligned with the rotational center of the benchtop device. The dynamometer was then programmed to operate in the isokinetic mode, where the input arm rotates at a specified angular velocity (10, 20, 30, and 45 degrees/s), while the resistive torque was logged using the dynamometer’s built-in functionality. Between trials, the area of magnetic field exposed to the disc was set to full exposure, half exposure, or no exposure to cover a range of resistive settings possible with the device. We then exchanged the disc for one of a different thickness and repeated the testing. Five trials were performed at each angular velocity and the average was used in further analysis. After characterizing the resistive properties of the device, we tuned the parameters (magnet size, number, etc.) to optimize wearability while maintaining a high resistance. The device was then fitted to an orthopedic knee brace that can fit across a wide range of patient sizes (5’ to 6’7”).The entire assembly weighed 1.6 kg (Fig. 2) and cost about $2100 for fabrication (including the brace).

FIGURE 2.

(a) Three-dimensional CAD rendering of the eddy current braking device. A slider allows us to change the area of magnetic field exposed to the disc, thus providing a variable torque. (b) A close-up view of the actual device showing the details of its attachment to a commercially available adjustable knee brace. (c) A subject wearing the device as it was in the experimental setup.

Human Subject Experiment

During phase two, the biomechanical effects of the wearable resistive device were tested on human subjects during a brief walking exercise under various loading conditions. Subjects (n = 7) with no signs of neurological or orthopedic impairment participated in the study. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the University of Michigan Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. Prior to the experiment, three 19 mm diameter retroreflective markers were placed over the subject’s right greater trochanter, lateral femoral epicondyle, and lateral malleolus. Additionally, eight surface electromyographic (EMG) electrodes (Trigno, Delsys, Natick, MA) were placed over the muscle bellies of vastus medialis (VM), rectus femoris (RF), medial hamstring (MH), lateral hamstring (LH), tibialis anterior (TA), medial gastrocnemius (MG), soleus (SO), and gluteus medius (GM) according to the established guidelines (www.seniam.org).23, 38 The EMG electrodes were tightly secured to the skin using self-adhesive tapes and cotton elastic bandages. The quality of the EMG signals was visually inspected to ensure that the electrodes were appropriately placed. The participant then performed maximum voluntary contractions (MVCs) of their hip abductors, knee extensors, knee flexors, ankle dorsiflexors, and ankle plantar flexors against a manually imposed resistance.23 The EMG activities obtained during the maximum contractions were used to normalize the EMG data obtained during walking.

The EMG and kinematic data were collected using custom software written in LabVIEW 2011 (National Instruments Corp., Austin, TX, USA). EMG data were recorded at 1000 Hz, and the kinematic data were recorded at 30 Hz using a real-time tracking system described elsewhere.24 Briefly, retroreflective markers placed on the hip, knee, and ankle joints were tracked using an image processing algorithm written in LabVIEW Vision Assistant. A three-point model was then created from the hip, knee, and ankle markers to obtain sagittal plane hip and knee kinematics using the following equations:

Where θHip (relative to the vertical trunk) and θKnee represent the anatomical joint angles, xhip, xknee and xankle represent the x-coordinates, and yhip, yknee and yankle represent the y-coordinates of the markers over the respective anatomical landmarks.

Experimental Protocol

A schematic of the experimental protocol is given in Fig. 3. Testing began by having the subject walk on a treadmill (Woodway USA, Waukesha, WI) at 2 mph. A two-minute warm-up period was provided, after which the subject performed a baseline walking trial (pre-BW) for one minute. The subject then wore the resistive brace (with a marker on its joint axis) on their right leg and performed nine walking trials, with each trial lasting one minute. A one-minute rest period was provided between each trial. With the device, the subject first performed one baseline walking with no resistance (pre-BWNR) to characterize the transparency of the device. The subject then performed two more baseline walking trials where the device was set to provide either medium (BWMR) or high resistance (BWHR). Following which, the subject performed three target matching (TM) trials where they viewed the ensemble average of their pre-BWNR foot trajectory on the monitor and attempted to match their foot trajectory with the target. The foot trajectory refers to the x-y position of the lateral malleolus with respect to the subject’s greater trochanter in the sagittal plane (Fig. 4), and was computed using a forward-kinematic model that used hip and knee joint angles and the segment lengths of the thigh and shank.1, 23 The target matching trials were performed for two reasons: (1) matching the template ensured that their hip and knee kinematics were similar to their unresisted baseline walking kinematics and (2) it allowed us to evaluate the feasibility of combining functional strength training with a motor learning task. During the three target matching trials, the resistance was set to low, medium, or high (corresponding to a quarter, half, and full magnetic exposure to the disc) to study the biomechanical effects of the device over a range of resistance settings. These trials were accordingly named as target matching with low resistance (TMLR), target matching with medium resistance (TMMR), and target matching with high resistance (TMHR). Following the target matching trials, the subject repeated the baseline walking with no resistance (post-BWNR) and baseline walking with no device (post-BW) trials. These trials were performed to see if there were any sustained changes in kinematics (i.e., aftereffects).

FIGURE 3.

Schematic of the experimental protocol.

FIGURE 4.

Sample ankle trajectories from a participant while walking on the treadmill under different loading conditions. The trajectories are x-y position of the lateral malleolus with respect to the greater trochanter of the hip in the sagittal plane. Ankle trajectories were computed using a forward-kinematic model that used hip and knee joint angles and the segment lengths of the thigh and shank. The leg’s position on the plot corresponds to the mid-swing phase of gait. The pre-BWNR refers to baseline walking with no resistance condition prior to the target matching conditions. The BWMR refers to baseline walking with medium resistance condition. Here, the height of the ankle trajectory (i.e., Ankle Y) was observed to reduce due to torque exerted by the device. The TMMR refers to target matching with medium resistance condition. During target matching, the participant viewed their pre-BWNR trajectory on the monitor and attempted to match their foot trajectory with the target. The TMMR trajectory was very similar to that of pre-BWNR, indicating the participant was able to match the target without any difficulty. Note that for clarity purposes, only three conditions are shown in the figure.

Data Analyses

Electromyography

The device’s effect on muscle activation was evaluated through the changes in EMG amplitude between walking conditions. The recorded raw EMG data were band-pass filtered (20–500 Hz), rectified, and smoothed using a zero phase-lag low-pass Butterworth digital filter (8th order, 6 Hz Cut-off).23 The resulting EMG profiles for baseline and target matching conditions were normalized using MVC contractions and ensemble averaged across strides to compute mean EMG profiles during each condition (EMG data of soleus muscle from one subject were excluded from the analysis due to electrode malfunction). Gait events were identified using accelerometer data collected from the Trigno™ EMG sensors. Ensemble averages of the gait cycle were then divided into two bins corresponding to the stance and swing phases of gait, and the average EMG activity was computed during each phase.

Kinematics

The kinematic data were ensemble averaged across strides and subjects to compute average profiles for each walking condition. The hip and knee excursions during baseline and target matching trials were calculated for each stride and averaged to determine the effect of resistive walking on sagittal plane kinematics, and to test the feasibility of target tracking during resisted walking. The hip and knee excursions during the first ten strides of the initial and final baseline walking conditions (i.e., pre-BW, pre-BWNR, post-BW, and post-BWNR) was averaged to recognize any short-lived aftereffects following the brief training with the resistive brace. Additionally, the instantaneous angular velocity of the knee joint during the target matching trials was calculated to estimate the resistance felt by the knee throughout the gait cycle.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for windows version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were computed for each variable and for assessing the results of benchtop testing. Prior to statistical analysis, the EMG data were log transformed (logeEMG) to minimize skewness and heteroscedasticity.16, 23 To examine the effect of the device on subjects’ muscle activation and joint kinematics during baseline walking, a linear mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) with trial (pre-BWNR, BWMR, and BWHR) as a fixed factor and subject as a random factor was performed for each muscle during each time bin.9, 16, 46 A significant main effect was followed by post-hoc analyses using paired t-tests with Šídák-Holm correction for multiple comparisons to compare resisted baseline walking trials (i.e., BWMR and BWHR) with the unresisted baseline walking trial (i.e., pre-BWNR). To examine the effect of the device on subjects’ muscle activation and joint kinematics during target matching trials, another linear mixed model ANOVA with trial (pre-BWNR, TMLR, TMMR, TMHR) as a fixed factor and subject as a random factor was performed for each muscle during each time bin. A significant main effect was followed by post-hoc analyses using paired t-tests with Šídák-Holm correction for multiple comparisons to compare resisted target matching trials (i.e., TMLR, TMMR, and TMHR) with the unresisted baseline walking trial (i.e., pre-BWNR). In order to evaluate the transparency of the device, paired t-tests were used to compare differences in muscle activation and joint kinematics between baseline walking with no device and baseline walking with no resistance trials (i.e., pre-BW and pre-BWNR). Paired t-tests were also used to compare differences in hip and knee joint excursions during the first ten strides between the pre-baseline and post-baseline walking trials (i.e., pre-BW vs. post-BW and pre-BWNR vs. post-BWNR) to identify significant aftereffects. A significance level of α = 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Benchtop Testing

The results of bench top testing verified that eddy current braking torque scaled linearly with velocity at the speeds used in this study (Fig. 5). The resistive torque was also proportional to the area of magnetic field exposed to the disc and the thickness of the disc; however, torque appeared to plateau after 3 mm of disc thickness (Fig. 5). Additionally, the maximum resistive torque attained using this small, portable form of eddy current braking was substantially large (26.85 N·m at 45 degrees per second using a 5mm thick disc; Fig. 5). This observation suggested that the benchtop device was capable of generating a peak torque of about 180 N·m during normal gait because the peak angular velocity of the knee during normal gait can exceed 300 degrees per second.18 This meant that the size and strength of the magnets used in the device, and therefore the weight, could be greatly reduced while still providing sufficient torque for functional strength training. For these reasons, the number of magnetic pairs used for braking was reduced from two to one, while the strength of the magnets was reduced by about half (DX04B-N52, KJ Magnetics, Pipersville, Pa) before fitting the device to the leg brace. The new brake was thus capable of providing about 56 N·m of torque during normal gait.

FIGURE 5.

Plots showing the results of benchtop testing performed on a Biodex isokinetic dynamometer with the eddy current braking device. The torques generated at various velocities were evaluated for discs of three different thicknesses (1 mm, 3 mm, and 5 mm) at three different exposure levels (no exposure, half exposure, and full exposure). As expected, the resistive torque scaled linearly with the velocity of the disc. The resistive torque was also proportional to the area of magnetic field exposed to the disc. The thickness of the disc also scaled the torque; however, torque appeared to plateau after 3 mm of disc thickness.

Human Subjects Experiment

Electromyographic changes during Baseline Walking

The muscle activation profiles observed during baseline walking trials are summarized in Fig. 6. There was a significant main effect of trial on EMG activity of vastus medialis [F(2,12) = 7.823; p = 0.007], medial gastrocnemius [F(2,12) = 17.696; p < 0.001], and soleus [F(2,10) = 5.021; p = 0.031] during the stance phase of gait. Post-hoc analysis indicated that the EMG activity of vastus medialis was significantly higher during resisted walking than during unresisted walking [BWMR: p = 0.020; BWHR: p = 0.006]. On the contrary, the medial gastrocnemius and soleus had significantly lower activation during resisted walking [MG BWMR: p = 0.046; MG BWHR: p < 0.001; SO BWHR: p = 0.021]. There was a significant main effect of trial on EMG activity of the tibialis anterior [F(2,12) = 4.026; p = 0.046] and soleus [F(2,10) = 4.187; p = 0.048] during the swing phase of gait. Post-hoc analysis showed a significant increase in soleus activation [BWHR: p = 0.032] and a trend towards significantly higher tibialis anterior activation [BWMR: p = 0.056; BWHR: p = 0.063] during resisted walking.

FIGURE 6.

Average electromyographic activity of each muscle during the baseline walking conditions. Traces show the mean ensemble averaged activation profiles (across all participants) during each walking condition, while bars show the average activation during the stance and swing phase of each condition. Note that muscle activation increased for many of the muscles tested. Error bars show the standard error of the mean. Daggers indicate significant differences between pre-baseline walking (pre-BW) and pre-baseline walking with no resistance (pre-BWNR) trials, and asterisks indicate significance of the resisted trials in comparison with the pre-baseline walking with no resistance (pre-BWNR) trial. BW: baseline walking; BWNR: baseline walking with no resistance; BWMR: baseline walking with medium resistance; BWHR: baseline walking with high resistance; VM: vastus medialis; RF: rectus femoris; MH: medial hamstring; LH: lateral hamstring; TA: tibialis anterior; MG: medial gastrocnemius; SO: soleus; GM: gluteus medius.

Kinematic changes during Baseline Walking

There was a significant main effect of trial on knee joint excursion during baseline walking [F(2,12) = 96.327; p < 0.001] with the device; however, no changes were observed for the hip joint [F(2,12) = 0.593; p = 0.568] (Fig. 7). Post-hoc analysis showed a significant reduction in knee joint excursion during resisted walking than during unresisted walking [BWMR: −28.6 ± 8.0°, p < 0.001; BWHR: −37.1 ± 8.3°, p < 0.001].

FIGURE 7.

Average kinematic data of the hip and knee joints during baseline walking conditions (top) and target matching conditions (bottom). Traces show the mean ensemble averaged joint angles (across all participants) during each walking condition. Note that knee flexion was greatly decreased during resisted baseline walking, but approached the level of baseline walking without resistance when subjects were given a target matching task. BW: baseline walking; BWNR: baseline walking with no resistance; BWMR: baseline walking with medium resistance; BWHR: baseline walking with high resistance; TMLR: target matching with low resistance; TMMR: target matching with medium resistance; TMHR: target matching with high resistance.

Electromyographic changes during Target Matching

The muscle activation profiles observed during target matching trials are summarized in Fig. 8. There was a significant main effect of trial on EMG activity of the vastus medialis [F(3,18) = 14.086; p < 0.001], rectus femoris [F(3,18) = 6.672; p = 0.003], medial hamstring [F(3,18) = 4.034; p = 0.023], lateral hamstring [F(3,18) = 7.268; p = 0.002] and gluteus maximus [F(3,18) = 6.619; p = 0.003] during the stance phase of gait. Post-hoc analysis indicated that the EMG activity was significantly greater during resisted target matching trials for the vastus medialis [TMMR: p < 0.001; TMHR: p < 0.001], rectus femoris [TMMR: p = 0.016; TMHR: p = 0.006], lateral hamstring [TMHR: p = 0.011], and gluteus medius [TMMR: p = 0.028; TMHR: p = 0.005] muscles. There was a significant main effect of trial on EMG activity of all the muscles during the swing phase of gait [F(3,18) = 4.871 to 27.519; p = 0.015 to p < 0.001]. Post-hoc analysis indicated the EMG activity was significantly greater during resisted target matching trials when compared with the unresisted baseline walking for all the muscles tested [p = 0.036 to p < 0.001; Fig. 8].

FIGURE 8.

Average electromyographic activity of each muscle during the target matching conditions. Traces show the mean ensemble averaged activation profiles (across all participants) during each walking condition, while bars show the average activation during the stance and swing phase of each condition. Note that muscle activation increased several folds for many of the muscles during both stance and swing phase of the gait. Error bars show the standard error of the mean and asterisks indicate significance in comparison with the pre-baseline walking with no resistance (pre-BWNR) trial. BWNR: baseline walking no resistance; TMLR: target matching with low resistance; TMMR: target matching with medium resistance; TMHR: target matching with high resistance; VM: vastus medialis; RF: rectus femoris; MH: medial hamstring; LH: lateral hamstring; TA: tibialis anterior; MG: medial gastrocnemius; SO: soleus; GM: gluteus medius.

Kinematic changes during Target Matching

There was a significant main effect of trial on hip [F(3,18) = 6.907; p = 0.003] and knee joint excursions [F(3,18) = 23.420; p < 0.001] during resisted target matching (Fig. 7). Post-hoc analysis showed that the hip joint excursions were greater during the target matching trials (TMMR: 4.5 ± 3.7°, p = 0.003; TMHR: 4.5 ± 3.1°, p = 0.002), but the knee joint excursions were smaller (TMLR: −7.8 ± 5.1°, p = 0.004; TMMR: −12.0 ± 7.2°, p < 0.001; TMHR: −16.4 ± 4.9°, p < 0.001) during the target matching trials when compared with baseline walking with no resistance.

Transparency of the device during baseline walking

The EMG profiles observed during baseline walking with no resistance were relatively similar to those observed during baseline walking without the device (Fig. 6). However, paired t-tests indicated small, but significantly greater activation of the rectus femoris (0.96 ± 1.03%; p = 0.035) and soleus (1.87 ± 1.76%; p = 0.030) muscles during the stance phase, and of the rectus femoris (1.0 ± 1.24%; p = 0.038), tibialis anterior (1.95 ± 1.94%; p = 0.017), and gastrocnemius (1.83 ± 3.64%; p = 0.029) muscles during the swing phase of the gait. There were no differences in hip (36.2 ± 2.8° and 39.1 ± 4.9°; p = 0.15) or knee (65.0 ± 2.5° and 69.6 ± 8.7°; p = 0.08) joint excursions during baseline walking and baseline walking with no resistance trials.

Kinematic Aftereffects of resisted target matching

A brief period of training with the device resulted in significant increases in knee joint excursions during baseline walking with no device (4.2 ± 2.6°; p = 0.005) and baseline walking with no resistance trials (5.4 ± 4.7°; p = 0.023) (Fig. 9a). Training also resulted in a significant increase in hip joint excursion during the baseline walking with no resistance trial (2.6 ± 1.6°; p = 0.005); however, no differences were observed in the baseline walking trial (−0.1 ± 1.4°; p = 0.825) (Fig. 9b).

FIGURE 9.

Plots showing changes in (a) knee joint and (b) hip joint excursions following a brief period (4 minutes) of training with the resistive brace. Note that hip and knee excursions increased after training; however, these aftereffects appear to be short-lived and reduced over time. BW: baseline walking; BWNR: baseline walking with no resistance.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop a wearable device that is capable of providing resistance across the knee joint for functional strength training of gait. We found that eddy current braking is a feasible option for this application, as our benchtop testing indicated that it can generate the torque required for functional strength training at a relatively small size and weight. Additionally, with the incorporation of a linear slider, we were able to obtain an adjustable resistance that can be regulated based on a subject’s impairment level and functional capacity. The results from the human subjects experiment also indicated that the device was largely transparent, as there were minimal alterations in hip/knee kinematics (3° to 5°) and lower extremity muscle activation (< 2% MVC). However, once the resistance was added, knee excursions reduced substantially. This was expected because the nervous system is known to optimize metabolic and movement related costs during walking or reaching movements.3, 37 Interestingly, despite the reduction in knee joint excursions during resisted baseline walking, muscle activation still increased in some of the muscles. More importantly, when subjects performed target tracking to minimize kinematic slacking (i.e., a phenomenon where the motor system reduces muscle activation levels and movement excursions to minimize metabolic and movement related costs28, 40) during resisted walking, the EMG activation increased several-fold in many of the muscles used in gait. Further, the aftereffects observed in hip and knee kinematics after a brief period of resisted target matching suggest that the device may have meaningful clinical potential, albeit further research is required to verify this premise.

The eddy current braking device is unique because it provides bidirectional resistance across the knee joint–as opposed to the endpoint–of the subject’s leg. Accordingly, muscle activation during target matching scaled largest around the knee joint. Interestingly, we also found that providing a resistance across the knee elicited increased activity of muscles spanning the hip and the ankle joints. These findings are consistent with previous studies23 and suggest that performing a motor learning task with the proposed device requires coordinated inputs from multiple muscles in the lower limb. The increased activation of the non-targeted muscles is potentially due to the synergistic and-or biarticular nature of some of the leg muscles (e.g. medial gastrocnemius), and recruitment of these muscles may have assisted in the process of overcoming the applied resistance.8, 23

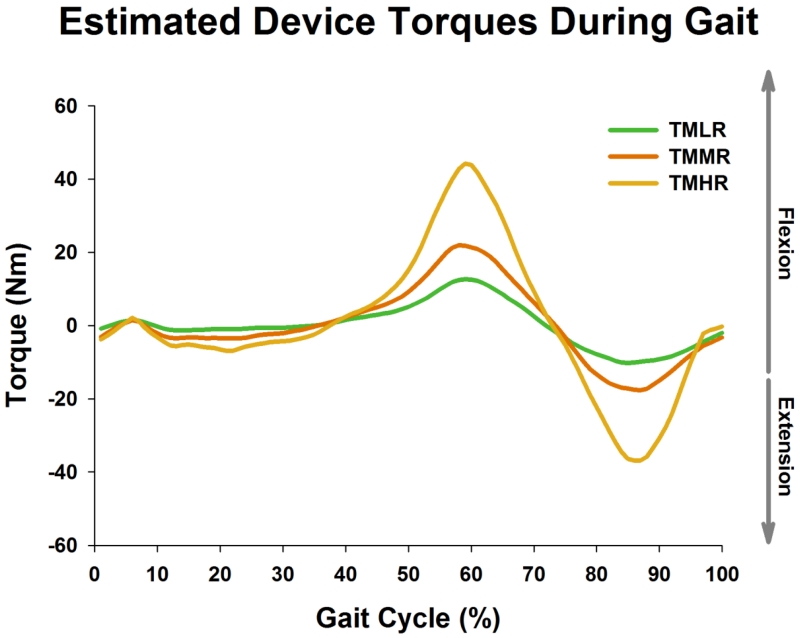

The eddy current brake in this study produced large resistive forces when compared to other wearable devices.44 The estimated resistive torques during the target matching trials ranged between 10 to 45 N·m (Figure 10), which are quite large considering the weight of the device. Also, changes in EMG activation were larger in comparison to those observed during walking with a 4 or 8 kg weight attached to the foot.4 These results suggest that eddy current braking is a suitable alternative to loading the lower limb muscles during walking. However, it is important to note that subjects reduced their joint excursions during resisted walking. As a result, the changes in muscle activation were subtle during simple resisted walking (i.e., baseline resisted walking): with some muscles showing lower activation. Incorporating a target tracking task effectively minimized the kinematic slacking observed during resisted baseline walking. Further, muscle activation increased several-fold during target tracking trials. These findings emphasize the importance of kinematic feedback during functional strength training, and failure to address kinematic slacking could reduce the effectiveness of functional strength training and promote compensatory movements. The kinematic feedback could also assist in minimizing off-plane motions (e.g., increased hip abduction/adduction) because the device in itself does not constrain those movements. In our experience, the device-induced off-plane motions were minimal (< 1°) in healthy subjects; however, certain patient populations (e.g., stroke) may behave differently due to abnormal synergistic coupling of motions across joints.22

FIGURE 10.

Data showing resistive torques applied by the device throughout the gait cycle during target matching. Resistive torques were estimated using the velocity profiles calculated from the kinematic data. TMLR: target matching with low resistance; TMMR: target matching with medium resistance; TMHR: target matching with high resistance.

While testing the clinical benefits of this device was not the focus of this study, the proposed device may have value in physical rehabilitation. Past research indicates that an ideal rehabilitation device should (1) encourage activities specific to daily living, (2) be able to be taken home, (3) have adjustable resistance to meet client needs, (4) have the potential to provide biofeedback to the clients, and (5) cost under $6000.27 The device in this study meets all these clinical guidelines. Additionally, functional strength training with this device is advantageous because it is not confined to treadmill training. Instead, training can take place over-ground, where the behavior is more specific to tasks encountered during daily living. Appropriate feedback can be administered during over-ground walking in the form of instructor/auditory feedback,15, 52 obstacle training,15 or even kinematic tracking using inertial measurement units.39 Given that the device is lightweight and portable, it could also be taken home to greatly amplify the dosage of therapy outside the clinical setting or in remote areas where rehabilitative care is not readily available. The device is also inherently safe because eddy current brakes are passive actuators that dissipate energy, as opposed to active motors that add energy to the system–with an active device, if there is a malfunction or error in the controls, unexpected motions could bring serious injuries to the user. Further, the clinical relevance of the device may extend outside of therapy for neurological injury. For example, because thigh muscle strength is critical for adequate lower limb function and quality of life,7, 12, 32, 42 we believe that the device could be beneficial for many subjects recovering from serious knee injuries, such as anterior cruciate ligament injury or repair, where thigh muscle strength deficits are profound.26

There were many design challenges faced while creating the device. Eddy current braking is capable of providing large levels of resistance, but these are generally coupled with high inertias.19 This limits the transparency of the device, as the resistive torque is dependent on the thickness, radius, and angular velocity of the disc, all of which increase rotational inertia. For this reason, we used a cable capstan coupling in our initial prototypes, as it allowed for a compact design with zero backlash during torque transmission, which provided a smoother feel to the user. However, the cable capstan was unable to withstand repeated wear. A planetary gearbox not only solved this issue, but also made the device modular (i.e., the gear ratios can be changed if necessary). However, we found that the set screws were prone to back off the gear shaft during repetitive loading. Adding an additional key on the gearing shaft and a through pin to the rotating shaft resolved this issue and kept the interfaces rigid without slipping. Further, by making the protruding arms of the device identical to those of the brace, the device fit seamlessly into the commercial leg brace. This proved to be a better option than superposing the device onto the brace, as it left the adjustability intact and reduced weight.

Further improvements are possible for better utilization of the device. The resistance setting of the current device is manually controlled using a linear slider. In the future, simple extensions to the design could be used to realize a computer-controlled resistance, with resistance programmed to be a function of time, gait kinematics, or muscle activations. For example, a small motor in conjunction with microprocessor control could be added to modulate the area of the magnet exposed on the aluminum disc. Besides keeping the device passive (as the motors would not directly act on the subject’s leg), it would also enable the therapist to modulate the resistance levels dynamically based on a subject’s rehabilitation needs. Moreover, bidirectional resistance may not be appropriate for all patient groups, such as those that have muscle imbalances across a joint. The addition of computer control or even a simple ratcheting mechanism, where the disc could be engaged and disengaged based on the direction of the movement, would enable the device to provide unidirectional resistance. This would allow the device to resist the weak agonist while not loading the stronger antagonist.

A key limitation of this study is that some of the kinematic changes observed may have been due to marker movements and kinematic model (relative to a vertical pelvis/trunk) used in this study. However, prior research indicates that sagittal plane motions are less affected due to marker movements and sagittal plane pelvic motions are minimal (<2°) during normal gait.2, 6 Thus, we believe that the changes observed in this study are much larger than the anticipated errors due to marker movements and kinematic model. Future research should consider incorporating a better kinematic model and 3D camera system to elucidate fully the biomechanical effects of the device on the wearer, particularly when testing patient population.

In summary, we fabricated a lightweight yet high torque eddy current brake and packaged it into a commercially available knee brace to create a wearable device that is capable of providing resistance across the knee joint for functional strength training. We also showed that the device increased muscle activation in many of the key muscles used in gait. Further, we demonstrated that a brief period of training with the resistive device induced positive kinematic aftereffects in both the hip and knee joints. These results demonstrate that the resistive device described in this study is a feasible and promising approach to actively engage and strengthen the key muscles used in gait. However, further testing in an injured population is warranted to determine the therapeutic benefits (e.g., strength, coordination, and neural plasticity) that could emerge from this unique application of functional strength training.

Acknowledgement

Research reported in this publication was supported by (1) National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) of the National Institutes of Health (Grant# R01EB019834), (2) Fostering Innovation Grants, and (3) University of Michigan Office of Research Grant. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. A special thanks to Stephanie Prout, Elizabeth Mays, and Sarah Abdulhamid for their assistance in creating preliminary versions of the device.

Abbreviations

- Pre-BW

Pre-Baseline Walking

- Pre-BWNR

Pre-Baseline Walking with No Resistance

- BWMR

Baseline Walking with Medium Resistance

- BWHR

Baseline Walking High Resistance

- TMLR

Target Matching with Low Resistance

- TMMR

Target Matching with Medium Resistance

- TMHR

Target Matching with High Resistance

- Post-BWNR

Post-Baseline Walking with No Resistance

- Post-BW

Post-Baseline Walking

- EMG

Electromyography

- MVC

Maximum Voluntary Contraction

References

- 1.Banala SK, Kim SH, Agrawal SK, Scholz JP. Robot assisted gait training with active leg exoskeleton (ALEX) IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2009;17:2–8. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2008.2008280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benoit DL, Ramsey DK, Lamontagne M, Xu L, Wretenberg P, Renstrom P. Effect of skin movement artifact on knee kinematics during gait and cutting motions measured in vivo. Gait Posture. 2006;24:152–164. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertram JE. Constrained optimization in human walking: cost minimization and gait plasticity. J. Exp. Biol. 2005;208:979–991. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browning RC, Modica JR, Kram R, Goswami A. The effects of adding mass to the legs on the energetics and biomechanics of walking. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007;39:515–525. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31802b3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll TJ, Selvanayagam VS, Riek S, Semmler JG. Neural adaptations to strength training: moving beyond transcranial magnetic stimulation and reflex studies. Acta physiologica. 2011;202:119–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castelli A, Paolini G, Cereatti A, Della Croce U. A 2D Markerless Gait Analysis Methodology: Validation on Healthy Subjects. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2015;2015:186780. doi: 10.1155/2015/186780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christiansen CL, Bade MJ, Weitzenkamp DA, Stevens-Lapsley JE. Factors predicting weight-bearing asymmetry 1month after unilateral total knee arthroplasty: a cross-sectional study. Gait Posture. 2013;37:363–367. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark DJ, Ting LH, Zajac FE, Neptune RR, Kautz SA. Merging of healthy motor modules predicts reduced locomotor performance and muscle coordination complexity post-stroke. J. Neurophysiol. 2010;103:844–857. doi: 10.1152/jn.00825.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins SH, Wiggin MB, Sawicki GS. Reducing the energy cost of human walking using an unpowered exoskeleton. Nature. 2015;522:212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature14288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corti M, McGuirk TE, Wu SS, Patten C. Differential effects of power training versus functional task practice on compensation and restoration of arm function after stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2012;26:842–854. doi: 10.1177/1545968311433426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damiano DL, Abel MF. Functional outcomes of strength training in spastic cerebral palsy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1998;79:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decker MJ, Torry MR, Noonan TJ, Sterett WI, Steadman JR. Gait retraining after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004;85:848–856. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobkin BH. Training and exercise to drive poststroke recovery. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2008;4:76–85. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duclos C, Nadeau S, Bourgeois N, Bouyer L, Richards CL. Effects of walking with loads above the ankle on gait parameters of persons with hemiparesis after stroke. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon) 2014;29:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan PW, Sullivan KJ, Behrman AL, Azen SP, Wu SS, Nadeau SE, Dobkin BH, Rose DK, Tilson JK, L. I. Team Protocol for the Locomotor Experience Applied Post-stroke (LEAPS) trial: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol. 2007;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duschau-Wicke A, Caprez A, Riener R. Patient-cooperative control increases active participation of individuals with SCI during robot-aided gait training. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2010;7:43. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-7-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eng JJ, Tang PF. Gait training strategies to optimize walking ability in people with stroke: a synthesis of the evidence. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2007;7:1417–1436. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg SR, Ounpuu S, Delp SL. The importance of swing-phase initial conditions in stiff-knee gait. J. Biomech. 2003;36:1111–1116. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gosline AH, Hayward V. Eddy current brakes for haptic interfaces: Design, identification, and control. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics. 2008;13:669–677. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hesse S. Locomotor therapy in neurorehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation. 2001;16:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim CM, Eng JJ. The relationship of lower-extremity muscle torque to locomotor performance in people with stroke. Phys. Ther. 2003;83:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnan C, Dhaher Y. Corticospinal responses of quadriceps are abnormally coupled with hip adductors in chronic stroke survivors. Exp. Neurol. 2012;233:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan C, Ranganathan R, Dhaher YY, Rymer WZ. A pilot study on the feasibility of robot-aided leg motor training to facilitate active participation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishnan C, Washabaugh EP, Seetharaman Y. A low cost real-time motion tracking approach using webcam technology. J. Biomech. 2015;48:544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langhorne P, Bernhardt J, Kwakkel G. Stroke rehabilitation. Lancet. 2011;377:1693–1702. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lepley LK. Deficits in Quadriceps Strength and Patient-Oriented Outcomes at Return to Activity After ACL Reconstruction: A Review of the Current Literature. Sports health. 2015;7:231–238. doi: 10.1177/1941738115578112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu EC, Wang RH, Hebert D, Boger J, Galea MP, Mihailidis A. The development of an upper limb stroke rehabilitation robot: identification of clinical practices and design requirements through a survey of therapists. Disability and rehabilitation. Assistive technology. 2011;6:420–431. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2010.544370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchal-Crespo L, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Review of control strategies for robotic movement training after neurologic injury. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2009;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mares K, Cross J, Clark A, Barton GR, Poland F, O’Driscoll ML, Watson MJ, McGlashan K, Myint PK, Pomeroy VM. The FeSTivaLS trial protocol: a randomized evaluation of the efficacy of functional strength training on enhancing walking and upper limb function later post stroke. Int. J. Stroke. 2013;8:374–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadeau SE, Wu SS, Dobkin BH, Azen SP, Rose DK, Tilson JK, Cen SY, Duncan PW, L. I. Team Effects of task-specific and impairment-based training compared with usual care on functional walking ability after inpatient stroke rehabilitation: LEAPS Trial. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2013;27:370–380. doi: 10.1177/1545968313481284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pak S, Patten C. Strengthening to promote functional recovery poststroke: an evidence-based review. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2008;15:177–199. doi: 10.1310/tsr1503-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmieri-Smith RM, Lepley LK. Quadriceps Strength Asymmetry After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Alters Knee Joint Biomechanics and Functional Performance at Time of Return to Activity. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015;43:1662–1669. doi: 10.1177/0363546515578252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patten C, Lexell J, Brown HE. Weakness and strength training in persons with poststroke hemiplegia: rationale, method, and efficacy. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2004;41:293–312. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2004.03.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Platz T. Impairment-oriented training (IOT)--scientific concept and evidence-based treatment strategies. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2004;22:301–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plautz EJ, Milliken GW, Nudo RJ. Effects of repetitive motor training on movement representations in adult squirrel monkeys: role of use versus learning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2000;74:27–55. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1999.3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollock A, Baer G, Campbell P, Choo PL, Forster A, Morris J, Pomeroy VM, Langhorne P. Physical rehabilitation approaches for the recovery of function and mobility following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD001920. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001920.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranganathan R, Adewuyi A, Mussa-Ivaldi FA. Learning to be lazy: exploiting redundancy in a novel task to minimize movement-related effort. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:2754–2760. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1553-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ranganathan R, Krishnan C. Extracting synergies in gait: using EMG variability to evaluate control strategies. J. Neurophysiol. 2012;108:1537–1544. doi: 10.1152/jn.01112.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rebula JR, Ojeda LV, Adamczyk PG, Kuo AD. Measurement of foot placement and its variability with inertial sensors. Gait Posture. 2013;38:974–980. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reinkensmeyer DJ, Akoner O, Ferris DP, Gordon KE. Slacking by the human motor system: computational models and implications for robotic orthoses. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2009;2009:2129–2132. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scandalis TA, Bosak A, Berliner JC, Helman LL, Wells MR. Resistance training and gait function in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001;80:38–43. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200101000-00011. quiz 44-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shelburne KB, Torry MR, Pandy MG. Effect of muscle compensation on knee instability during ACL-deficient gait. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005;37:642–648. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000158187.79100.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simeu E, Georges D. Modeling and control of an eddy current brake. Control Eng. Pract. 1996;4:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sulzer JS, Roiz RA, Peshkin MA, Patton JL. A Highly Backdrivable, Lightweight Knee Actuator for Investigating Gait in Stroke. IEEE transactions on robotics : a publication of the IEEE Robotics and Automation Society. 2009;25:539–548. doi: 10.1109/TRO.2009.2019788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Krogt MM, Bregman DJ, Wisse M, Doorenbosch CA, Harlaar J, Collins SH. How crouch gait can dynamically induce stiff-knee gait. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010;38:1593–1606. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9952-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.West BT, Welch KB, Galecki AT. Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide Using Statistical Software. Vol. 440. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wouterse J. Critical torque and speed of eddy current brake with widely separated soft iron poles. IEE Proc-B. 1991;138:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu M, Hornby TG, Landry JM, Roth H, Schmit BD. A cable-driven locomotor training system for restoration of gait in human SCI. Gait Posture. 2011;33:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu M, Landry JM, Kim J, Schmit BD, Yen SC, Macdonald J. Robotic resistance/assistance training improves locomotor function in individuals poststroke: a randomized controlled study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014;95:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang YR, Wang RY, Lin KH, Chu MY, Chan RC. Task-oriented progressive resistance strength training improves muscle strength and functional performance in individuals with stroke. Clin. Rehabil. 2006;20:860–870. doi: 10.1177/0269215506070701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yen SC, Schmit BD, Wu M. Using swing resistance and assistance to improve gait symmetry in individuals post-stroke. Hum Mov Sci. 2015;42:212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zanotto D, Rosati G, Spagnol S, Stegall P, Agrawal SK. Effects of complementary auditory feedback in robot-assisted lower extremity motor adaptation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2013;21:775–786. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2013.2242902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]