Abstract

Background

Total knee replacement is an effective treatment for knee arthritis. While the majority of TKAs have demonstrated promising long-term results, up to 20 % of patients remain dissatisfied with the outcome of surgery at 1 year. Implant malalignment has been implicated as a contributing factor to less successful outcomes. Recent evidence has challenged the relationship between alignment and patient reported outcome measures. Given the number of procedures per year, clarity on this integral aspect of the procedure is necessary.

Objective

To investigate the association between malalignment and PROMS following primary TKA.

Methods

A systematic review of MEDLINE, CINHAL, and EMBASE was carried out to identify studies published from 2000 onwards. The study protocol including search strategy can be found on the PROSPERO database for systematic reviews.

Results

From a total of 2107 citations, 18 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria, comprising of 2214 patients. Overall 41 comparisons were made between a malalignment parameter and a PROM, with 30 comparisons (73 %) demonstrating no association. However, 50 % (n = 9) of the studies with ‘Low risk’ radiological assessment methods have reported a statistically significant association between one or more parameter of malalignment and PROMS.

Conculsion

When considering malalignment in an individual parameter, there is an inconsistent relationship with PROMs scores. Malalignment may be related to worse PROMs scores, but if that relationship exists it is weak and of dubious clinical significance. However, this evidence is subject to limitations mainly related to the methods of assessing alignment post operatively and by the possibility that the premise of traditional mechanical alignment is erroneous. Larger longitudinal studies with a standardised, timely, and robust method for assessing alignment outcomes are required.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2790-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

Total knee Replacement (TKR) is considered an effective treatment for knee arthritis (Callahan et al. 1994). Over 77,000 TKA operations were performed during 2013 in England and Wales (Registry 2013) with expectations of increasing demand (Kane et al. 2003). While the majority of TKAs demonstrate significantly improved pain relief and function results (van Essen et al. 1998; March et al. 1999; Anderson et al. 1996), up to 20 % of patients remain unsatisfied with the outcome of surgery at 1 year (Kim et al. 2009; Scott et al. 2010; Baker et al. 2007; Robertsson et al. 2000; Bourne et al. 2010).

To ensure optimisation, an important technical objective during surgery is to achieve a perfect tri-planar component alignment (Sikorski 2008) with a neutrally aligned limb and a mechanical axis of 180° ± 3° and no tibio-femoral rotational mismatch (Ritter et al. 1994; Nicoll and Rowley 2010; Moreland 1988; Longstaff et al. 2009; Werner et al. 2005; Lotke and Ecker 1977; Bargren et al. 1983; Tew and Waugh 1985).

Three reasons to challenge the view that alignment in total knee replacements is of paramount importance have emerged (Eckhoff et al. 2005). Firstly, it is suggested that the evidence of poor outcomes secondary to malalignment is largely historic, based on studies of inferior implant designs (Bach et al. 2009; Bonner et al. 2011; Matziolis et al. 2010; Parratte et al. 2010), and the use of poor radiological techniques when assessing malalignment (Lotke and Ecker 1977). Secondly, outcomes following computer assisted TKA, proven to achieve better target alignment in comparison to conventional techniques, have demonstrated little evidence of clinical advantage (Matziolis et al. 2010; Cheng et al. 2012a). Thirdly, the choice of target for ideal alignment has been challenged by proponents of kinematically aligned TKA who have reported promising results (Howell et al. 2013a, b). Kinematic alignment aims to place the femoral component so that its transverse axis coincides with the primary transverse axis in the femur about which the tibia flexes and extends. As this axis is centred on the posterior condyles of the femur, which is not parallel to any standard coronal, sagittal or axial view, it is not measurable by standard means. With the removal of osteophytes the original ligament balance can be restored and the tibial component is placed with a longitudinal axis perpendicular to the transverse axis in the femur.

We performed a systematic review of the literature to answer the following research question: In patients undergoing primary total condylar knee replacement is malalignment, assessed radiologically, associated with functional outcomes and/or PROMs.

Methods

This review followed the guidelines described by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) criteria (Viswanathan et al. 2008a). The review has been registered and published on the PROSPERO database; Protocol Number 2012:CRD42012001914 (Hadi et al. 2012).

Literature search

A literature search of the following databases was carried out: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online, Bethesda, Maryland, USA (MEDLINE), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Glendale, California USA (CINHAL), Excerpta Medica Database, Amsterdam, the Netherlands (EMBASE). A broad search strategy using MeSH terms “knee”, “replacement”, “alignment” and “outcome” was adopted. This was intended to identify English-language studies published from 2000 through to 2014. The search was restricted to this period to avoid the inclusion of studies with potentially poor implant designs and weak radiological assessment methods. The search was last performed on September 2014.

Eligibility criteria

Both observational and experimental designs were considered for inclusion in this review.

Inclusion criteria:

All patients who were deemed eligible for a primary TKA were considered.

All open procedures that used a total condylar knee replacement.

All described approaches.

All radiological alignment assessment methods and parameters described.

Exclusion criteria:

Studies that have fulfilled the inclusion criteria but have not provided adequate or clear information on the correlation analysis between malalignment and PROMs.

Studies with a mean follow-up of <6 months,

Abstract-only publications, expert opinions and chapters from books.

Extraction of data

Two investigators (MH, TB) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts to identify and retrieve all articles relevant to our research questions, disagreements were settled by consensus between the two reviewers or with a third investigator (MD).

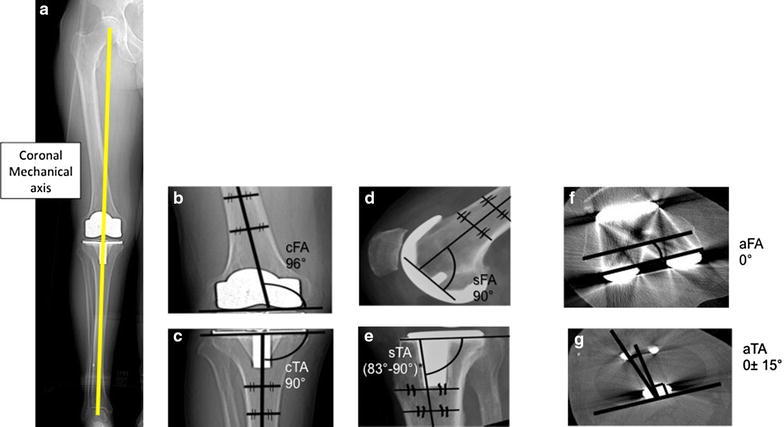

The parameters of malalignment are illustrated in Fig. 1. For the purposes of this review we describe coronal alignment as the mechanical alignment, and describe the method of assessment (long leg or short leg radiograph).

Fig. 1.

A diagrammatic representation of different alignment parameters based on The Knee Society Total Knee Arthroplasty Roentgenographic Evaluation and Scoring System (Viswanathan et al. 2008a). The Coronal Tibiofemoral mechanical angle is the angle resulting from drawing a line from the centre of the femoral head down to centre of the ankle through the centre of the knee a ideally 180°. The coronal femoral angle cFA b ideally 96°—and coronal tibial angle cTA, c ideally 90°—are the angles between the components’ coronal axes (the line connecting the femoral components most distal condyles and the line along the horizontal tibial plate) and the bones’ coronal anatoical axes (line which bisects the medullary canal of the femur and tibia respectively). The coronal tibiofemoral anatomical angle is a combination of the coronal anatomical femoral axis and coronal anatomical tibial axis. The sagittal femoral sFA, d ideally 90°—and sagittal tibial sTA, e ideally between 83° and 90°—angles are the angles between the components’ sagittal axes (horizontal line perpendicular to the femoral component peg and line along the horizontal tibial plate) and the anatomical sagittal bones’ axes (line which bisects the medullary canal of the femur and tibia respectively). The axial femoral (aFA) f ideally 0°—and axial tibial—ideally within 15°—(aTA), g angles are the angles between the components’ axial axes (line through the centre of the femoral pegs and the line through the most posterior points of the tibial plate on axial views respectively) and the bones’ axial axes (surgical epicondylar femoral axis and the tibial tuberosity axis respectively). The combined components axial (aCRA) rotational alignment angles—ideally 0°—is the angle between the components axial axes

Quality assessments of included studies

All studies were assessed for their methodological qualities in accordance with their study design. Case control and Cohort studies were assessed using the Ottawa–Newcastle score system (Stang 2010). RCTs and Case series were assessed using an AHRQ design-specific scales (Viswanathan et al. 2008b).

Studies were further evaluated based on the quality of their radiological methods for assessing alignment. The evaluation was done using a five-question checklist devised for this review; the Radiological Assessment Quality (RAQ) criteria (Hadi et al. 2015). The items in the checklist together with their corresponding justification are described in the Additional file 1. Studies were deemed as low, unclear or high risk of assessment bias based on the radiological methods described. Sensitivity analysis using radiological assessment quality did not alter the results.

Statistical analysis

Due the exploratory nature of the research question, the summary of data was focused on descriptive statistics and qualitative assessment of the content of the identified literature. Meta-analysis was not part of the study protocol and was not conducted as the outcome measures, measure of alignment, and methods of assessment were heterogeneous. Given these limitations, it was thought it would produce a precise, but potentially spurious result (Egger et al. 1998).

Results

Search results

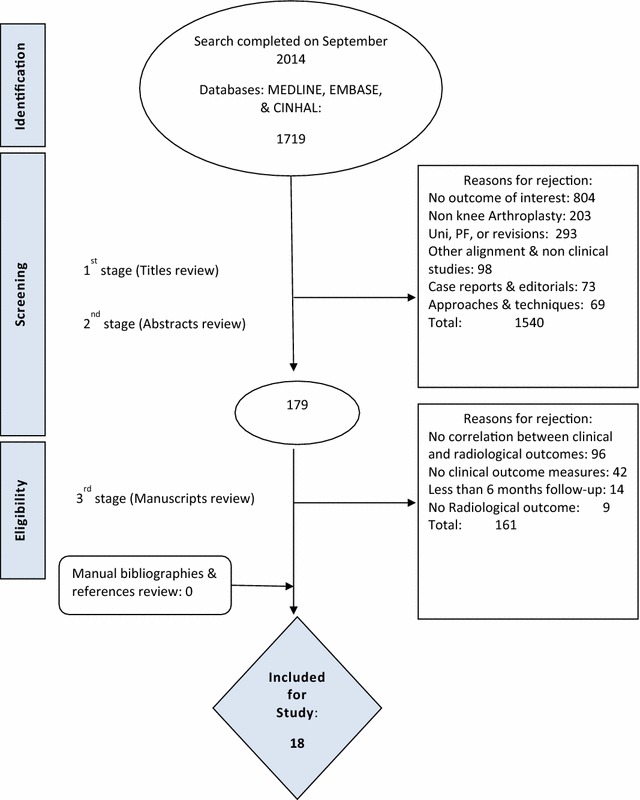

The initial search returned 2107 citations, of which 1719 were considered for screening. Details of the study selection process are described in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flow diagram including the details of our search results for this review. Figure shows the reasons behind study exclusion at each stage of the search and the number of studies identified at each point of the search

A total of 18 studies (Nicoll and Rowley 2010; Longstaff et al. 2009; Bach et al. 2009; Matziolis et al. 2010; Howell et al. 2013b; Aglietti et al. 2007; Bankes et al. 2003; Barrack et al. 2001; Bell et al. 2014; Blakeney et al. 2014; Choong et al. 2009; Czurda et al. 2010; Gothesen et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2012; Lutzner et al. 2010; Magnussen et al. 2011; Rienmuller et al. 2012; Stulberg et al. 2008) fulfilled the review inclusion criteria, including five RCTs (Blakeney et al. 2014; Choong et al. 2009; Gothesen et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2012; Lutzner et al. 2010), seven case control studies (Nicoll and Rowley 2010; Matziolis et al. 2010; Barrack et al. 2001; Bell et al. 2014; Czurda et al. 2010; Magnussen et al. 2011; Stulberg et al. 2008) and 6 case series (Longstaff et al. 2009; Bach et al. 2009; Howell et al. 2013b; Aglietti et al. 2007; Bankes et al. 2003; Rienmuller et al. 2012). The methodological quality-assessment of included studies is presented in Tables 1, 2 and 3. The results did not alter with subgroup analysis based on quality assessment.

Table 1.

Quality assessment criteria for RCTs

| Authors | Quality assessment | Judgment on risk of bias | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was the allocation sequence generated adequately? | Was the allocation of treatment adequately concealed | Did researchers rule out any unintended exposure that might bias results? | Were participants analysed within the groups they were originally assigned to? | Was the length of follow-up different between the groups | Were the outcome assessors blinded to the intervention or exposure status of participants? | Were the potential outcomes pre-specified by the researchers? Are all pre-specified outcomes reported? | If attrition was a concern were missing data handled appropriately? | Were outcomes assessed using valid and reliable measures across all study participants? | ||

| Blakeney et al. (2014) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low risk |

| Choong et al. (2012) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low risk |

| Huang et al. (2012) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low risk |

| Lutzner et al. (2010) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low risk |

| Gothesen et al. (2014) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low risk |

Assessed using AHRQ design specific scale (Stang 2010)

Table 2.

Quality assessment of Case control and Cohort studies

| Author | Quality assessment of case control studies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is the case definition adequate? | Representativeness of the cases | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Comparability of cases and controls on basis of design or analysis | Ascertainment of exposure | Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls | Non-Response rate | Total Newcastle Ottawa Scale (possible 9 starts) | |

| Barrack et al. (2001) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8* |

| Bell et al. (2014) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8* |

| Czurda et al. (2010) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 7* |

| Magnussen et al. (2011) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 7* |

| Matziolis et al. (2010) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8* |

| Nicoll and Rowley (2010) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8* |

| Stulberg et al. (2008) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8* |

Assessed using the Ottawa-Newcastle score (Viswanathan et al. 2008a)

* Represents how many stars were achieved in the assessment of quality for each study

Table 3.

Quality assessment of Case series studies

| Author | Quality assessment of case series | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consecutive selection of patients? | Were outcomes measured in an objective way? | Were confounders identified and controlled? | Was follow up sufficiently long and complete | |

| Aglietti et al. (2007) | Yes | ? | No | Yes |

| Bach et al. (2009) | Yes | ? | No | Yes |

| Bankes et al. (2003) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Howell et al. (2013b) | ? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Longstaff et al. (2009) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rienmüller et al. (2012) | Yes | ? | No | Yes |

Assessed using AHRQ design specific scale (Stang 2010)

The total number of patients recruited in all included studies was 2214 patients. Minimal patient baseline characteristics were reported, however, where reported they were comparable between studies. Study characteristics can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Study characteristics of included studies in this review

| Author and journal | Study design | Sample size | Follow up (mean range) | Number of patients lost to follow up | Final study sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choong et al. (2012) J Athro | RCT (single centre) | 120 | 1 year | 9 | 111 |

| Lutzner et al. (2010) Knee Surg. Sports Trauma Arthos | RCT (single centre) | 80 | 1.8 years | 7 | 73 |

| Huang et al. (2012) Journal of Arthoplasty | RCT (single centre) | 111 | 5 years | 21 | 90 |

| Blakeney et al. (2014) The Knee | RCT (single centre) | 107 | 46 months | 14 | 93 |

| Gothesen et al. (2014) JBJS | RCT (multi-centre) | 194 | 5 years | 19 | 175 |

| Barrack et al. (2001) CORR | Case control (single centre) | 30 | 5.7 years | 2 | 28 |

| Stulberg et al. (2008) Orthopaedics | Case control (single centre) | 58 | 2.5 years | 6 | 52 |

| Nicoll and Rowley (2010) JBJS | Case control (single centre) | 61 | >1 year | 23 | 39 |

| Matziolis et al. (2010) Arch Orthop Trauma Surg | Case control (single centre) | 218 (from a database) | 5–10 years | 168 | 50 |

| Czurda et al. (2010) Knee Surg Sport Trau Arthrosc | Case control (single centre) | 38 | 2.2 years | 0 | 38 |

| Magnussen et al. (2011) CORR | Case control (single centre) | 608 | Median 4.7 years (2–19.8) | 55 | 553 |

| Bell et al. (2014) The Knee | Case control (single centre) | 127 | 1 year | 15 | 112 |

| Bankes et al. (2003) The Knee | Case series (single centre) | 198 | 6.5 years | 0 | 198 |

| Aglietti et al. (2007) CORR | Case series (single centre) | 64 | 8 Years | 19 | 53 |

| Longstaff et al. (2009) J Arthro | Case series (single centre) | 159 | 1 year | 9 | 146 |

| Bach et al. (2009) The Knee | Case series (single centre) | 105 | 10.8 years | 7 | 98 |

| Rienmüller et al. (2012) International Orthopaedics | Case series (single centre) | 219 | 5 Years | 15 | 204 |

| Howell et al. (2013b) Knee Surg Sport Trau Arthrosc | Case series (single centre) | 101 | 6–9 months | 1 | 101 |

The functional and PROMS outcomes identified in this review included: Knee Society Score (KSS), Hospital for Special Surgery Score (HSS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), SF-12, SF-36, EuroQol, patella-femoral symptoms Score, Bristol score, Nottingham health profile, Visual analogue scale (VAS).

Out of the possible malalignment parameters considering the component’s six degrees of freedom, ten parameters were reported. Multiple different measures were used to measure coronal alignment, with varying nomenclature. Sagittal and axial alignments of the tibial and femoral components were not subject to this confusing nomenclature. See the Additional file 1 for a full description of each alignment parameter with detailed findings from each paper.

Quality assessment

Tables 1 and 2 demonstrate the quality assessment of each included study.

Radiological assessment

Table 5 demonstrates the radiological characteristics of each study using the RAQ criteria.

Table 5.

Radiological methods quality assessment of included studies

| Author | Modality of image | Timing of image | Weight bearing | Protocol/standardisation | Rater reliability assessment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choong et al. (2012) | CT, LLR | 6 weeks | Y | Y | N | Low risk |

| Lutzner et al. (2010) | CT, LLR | 18–32 months | Y | U | N | High risk |

| Huang et al. (2012) | CT, LLR | 6 weeks | Y | Y | N | Low risk |

| Blakeney et al. (2014) | CT (3D) | 3 months | N | Y | N | Medium risk |

| Gothesen et al. (2014) | CT, LLR | 3 months | Y | Y | N | Low risk |

| Barrack et al. (2001) | CT, LLR | At latest follow up | Y | U | N | High risk |

| Stulberg et al. (2008) | LLR, SLR, Navigation system | 4 weeks and 2 years | Y | Y | N | Low risk |

| Nicoll and Rowley (2010) JBJS | CT, SLR | At least 1 year after TKR | N | U | N Senior author | High risk |

| Matziolis et al. (2010) | LLR | Latest follow up | Y | Y | Y | High risk |

| Czurda et al. (2010) | CT, LLR | At 1st follow up | Y | Y | N Independent radiologist | Low risk |

| Magnussen et al. (2011) | LLR | Follow up (varied) | Y | Y | Y | High risk |

| Bell et al. (2014) | CT | 26 months | N | U | MSK radiologist | High risk |

| Bankes et al. (2003) | SLR | 3 and 12 month follow up | Y | Y | N | Low risk |

| Aglietti et al. (2007) | LLR | Latest follow up | Y | Stress to assess varus-valgus stability | N | High risk |

| Longstaff et al. (2009) | CT | 6 months | N | Y | Y | Low risk |

| Bach et al. (2009) | SLR | At follow up | N | Y | N Experienced radiologist | High risk |

| Rienmüller et al. (2012) | LLR, Axial XR | 5 years | N | Y | Y | High risk |

| Howell et al. (2013b) | CT | 2 days | N | Y | N | Medium risk |

We devised a 5 point checklist (Fig. 2) and all studies were assessed using this checklist to identify whether they were high/low risk

CT computerised tomography, LLR long leg radiograph, SLR short leg radiograph, Y yes, N no, U unknown

Association between malalignment and patient reported outcome measures (PROMs)

Overall 41 comparisons were made between a malalignment parameter and a PROM, with 30 comparisons (73 %) demonstrating no association. Of the 18 studies, 12 studies (67 %) demonstrated an association between malalignment in one or more parameter of alignment and a worse patient reported outcome. Of these, nine studies (50 %) applied radiological methods with a low or medium risk of bias.

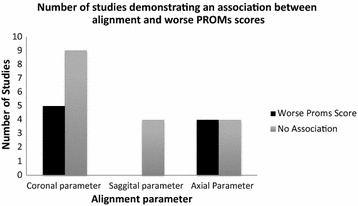

We summarised the association between malalignment and PROMs according to the plane of assessment and the individual components.

In the coronal plane, five out (Longstaff et al. 2009; Cheng et al. 2012a; Aglietti et al. 2007; Blakeney et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2012) of fourteen studies (Nicoll and Rowley 2010; Longstaff et al. 2009; Bach et al. 2009; Matziolis et al. 2010; Cheng et al. 2012a; Howell et al. 2013b; Aglietti et al. 2007; Bankes et al. 2003; Blakeney et al. 2014; Czurda et al. 2010; Gothesen et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2012; Magnussen et al. 2011; Stulberg et al. 2008) showed an association between malalignment in the coronal plane and worse PROM scores (Table 6; Fig. 3) provide graphical representation of this.

Table 6.

Association between coronal malalignment and worse outcome

| Author | Sample size | Type of radiograph | RAQ score | Outcome measure | Malalignment parameter | Association between malalignment and worse outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aglietti et al. (2007) | 53 | LL | High risk | KSS (Clinical) HHS Patella score | cTFmA | Yes |

| Choong et al. (2012) | 111 | LL | Low risk | IKS SF-12 | cTFmA | Yes |

| Blakeney et al. (2014) | 93 | CT | Medium risk | SF-12 OKS | cTFmA | Yes |

| Huang et al. (2012) | 90 | LL | Low risk | IKS SF-12 | cTFmA | Yes |

| Longstaff et al. (2009) | 146 | CT | Low risk | KSS | cTA, cFA | Yes |

| Howell et al. (2013b) | 101 | CT | Medium risk | OKS WOMAC | cTFmA, cTA | No |

| Magnussen et al. (2011) | 553 | LL | High risk | KSS | cTFmA, cTA, cFA | No |

| Matziolis et al. (2010) | 50 | LL | High risk | KSS WOMAC SF36KSS | cTFmA, cTA, cFA | No |

| Stulberg et al. (2008) | 52 | LL | Low risk | KSS | cTFmA | No |

| Gothesen et al. (2014) | 175 | LL | Low risk | KSS | cTFmA, cTA, cFA | No |

| Czurda et al. (2010) | 38 | LL | Low risk | WOMAC KSS | cTFmA, cFA | No |

| Bach et al. (2009) | 98 | SL | High risk | KSS, HSS, Bristol score, NHP | cTFaA, cTA, cFA | No |

| Bankes et al. (2003) | 198 | SL | Low risk | KSS | cTFaA, cTA, cFA | No |

| Nicoll and Rowley (2010) | 45 | SL | High risk | KSS | cTFaA, cTA, cFA | No |

KSS knee society score, HHS harris hip score, NHP Nottingham health profile, WOMAC Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis index, OKS Oxford knee score, SF-12 short form-12, cTFmA coronal tibio-femoral mechanical alignment, cTFaA coronal tibio-femoral anatomical alignment, cTA coronal tibial alignment, cFA coronal femoral alignment, LL long leg radiograph, SL straight leg radiograph

Fig. 3.

Graph demonstrating the number of studies demonstrating an association between malalignment and worse PROMs (patient reported outcome measures) scores based on imaging in the coronal, sagittal and axial view

Only four studies (Longstaff et al. 2009; Bach et al. 2009; Bankes et al. 2003; Stulberg et al. 2008) investigated sagittal malalignment and its relationship with PROM, with none of these demonstrating a statistically significant association between femoral or tibial malalignment and worse outcomes (Table 7; Fig. 3).

Table 7.

Association between sagittal malalignment and worse outcome

| Author | Sample size | Type of radiograph | RAQ score | Outcome measure | Malalignment parameter | Association between malalignment and worse outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bankes et al. (2003) | 198 | SL | Low risk | KSS | sFA, sTA | No |

| Bach et al. (2009) | 98 | SL | High risk | KSS, HSS, Bristol score, NHP | sFA, sTA | No |

| Stulberg et al. (2008) | 52 | LL | Low risk | KSS | sFA, sTA | No |

| Longstaff et al. (2009) | 146 | CT | Low risk | KSS | sFA, sTA | No |

KSS knee society score, HSS hospital for special surgery score, NHP Nottingham health profile, sTA sagittal tibial angle, sFA sagittal femoral angle, LL long leg radiograph, SL straight leg radiograph

Four (Barrack et al. 2001; Bell et al. 2014; Czurda et al. 2010; Lutzner et al. 2010) out of eight studies (Nicoll and Rowley 2010; Longstaff et al. 2009; Howell et al. 2013b; Barrack et al. 2001; Bell et al. 2014; Czurda et al. 2010; Lutzner et al. 2010; Rienmuller et al. 2012) found a statistically significant association between malalignment in the axial view and worsening patient reported outcome measures (Table 8; Fig. 3).

Table 8.

Association between axial malalignment and worse outcome

| Author | Sample size | Type of radiograph | RAQ score | Outcome measure | Association between malalignment and worse outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrack et al. (2001) | 28 | CT, LLR | High risk | KSS | Yes |

| Bell et al. (2014) | 112 | CT | High risk | OKS VAS | Yes |

| Lutzner et al. (2010) | 73 | CT, LLR | High risk | KSS | Yes |

| Czurda et al. (2010) | 38 | CT, LLR | Low risk | WOMAC KSS | Yes |

| Rienmüller et al. (2012) | 204 | LLR, Axial XR | High risk | KSS | No |

| Howell et al. (2013b) | 101 | CT | Medium risk | OKS WOMAC | No |

| Nicoll and Rowley (2010) | 45 | CT, SLR | High risk | KSS | No |

| Longstaff et al. (2009) | 146 | CT | Low risk | KSS | No |

KSS knee society score, WOMAC Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index, OKS Oxford knee score, VAS visual analogue score for pain, LL long leg radiograph, SL straight leg radiograph

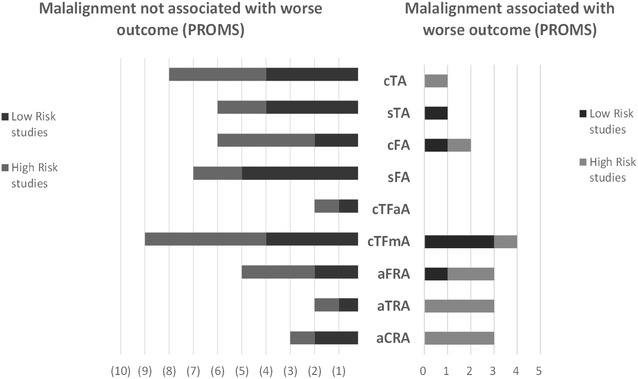

Finally, Fig. 4 demonstrate the rate each individual malalignment parameter’s association with PROMS outcome. The chart highlights the number of studies with low and high risk for radiological assessment bias as per the RAQ criteria.

Fig. 4.

Graph demonstrating rate each malalignment parameter is reported to associate with outcome. Studies are divided into with low and high risk of radiological assessment bias as per he RAQ criteria. cTA coronal tibial angle, sTA sagittal tibial angle, cFA coronal femoral angle, sFA sagittal femoral angle, cTFmA coronal tibio-femoral mechanical angle, cTFaA coronal tibiofemoral anatomical angle, aFRA axial femoral rotational angle, aTRA axial tibial rotational angle, aCRA axial combined rotational/mismatch angle

Discussion

The main findings of this review were that 50 % (n = 9) of the studies with ‘Low risk’ radiological assessment methods have reported a statistically significant association between one or more parameter of malalignment and PROMS. Overall 41 comparisons were made between a malalignment parameter and outcome within the included studies, with only 11 comparisons (27 %) demonstrating an association. With a p value of 0.05, we would expect two of these associations by chance. This suggests that the effect of malalignment on PROMs is likely to be small and it is unclear from this review the clinical significance of this finding. When assessing each parameter individually:

Coronal malalignment

In the literature, coronal malalignment is seen regarded as one of the most important factors determining the long-term prosthesis survival. Several authors stressed the importance of restoring limb coronal mechanical alignment to within 180°. In this review, as many as 64 % of studies investigating alignment in the coronal plane showed no associated between malalignment and worse outcome measures.

Sagittal malalignment

Components malalignment on this plane can alter the posterior tibial slop and affect the flexion and extension gaps. This may result in overstuffing and limited joint range. Femoral notching can be seen in excessive femoral component extension position. However, 100 % of studies reviewed in this review showed no associated between sagittal malalignment and worse outcome measures.

Axial malalignment

Many references exist for measuring femoral and tibia component rotation. Individual component malalignment and combined mismatch can result in abnormal patella tracking and subsequent anterior knee pain. Our review show 50 % of studies found an association between malalignment and worse PROMs.

Strengths and limitations

Several caveats exist in interpreting this paper, mostly based on the limitations of the studies involved, and the complexity of the topic in general. There is a lack of consistency in the way different studies assessed alignment following a TKA. For example, the use of long leg and short leg radiographs. When using long leg radiographs a direct comparison between the mechanical axis and the femoral and tibial alignment can be made in the coronal plane. If using a short leg radiograph an indirect assessment is made, based on the assumption that the intramedullary canal of the femur deviates 6° from the mechanical axis. In reality this deviation is variable, making this assessment method less accurate. To address this, a RAQ checklist was devised to assess the radiological methods, although this did not alter the overall results of the review by sub-analysis. These variations in methodology (combined with variation in PROMS scores) make meta-analysis problematic.

Furthermore, a number of studies restricted their analysis to one or two parameters of alignment. This approach is problematic given the relative interconnection between the alignment components in a TKA (Berend et al. 2004; Ritter et al. 2011). Berend et al. (2004) found the effect of malalignment in one implant moderated by the alignment of the other. Ritter et al. (2011) concluded that correction of the alignment of the second component in order to produce an overall neutrally aligned knee replacement when the first component has been malaligned may increase the risk of failure. These findings suggest a complex interplay between all measures of alignment in both the tibial and the femoral components that cannot be simplified to conventional definitions of “malaligned” or “aligned”. Given that some studies did not report findings for certain parameters there is the potential for publication bias as studies where no relationship was found contained missing data.

In addition, the parameters of malalignment were poorly defined. Studies presented malalignment data either in terms of deviation from the leg axis in the arithmetic mean or as two groups of ‘Aligned’ versus’ Malaligned’ or ‘Outliers’. While the majority of studies applied a ±3° range around a perfect alignment measurement, some studies had a more stringent criterion applying a ±2° range. Applying this narrow range, Longstaff et al. (2009) found better functional outcomes with good coronal femoral alignment and only a trend to better function at 1 year on patients with ‘good’ coronal tibial and ‘good’ sagittal tibial and sagittal femoral alignment.

The characteristics of the patient-related clinical outcome measures used by the studies included in this review may have contributed to the quality of the evidence presented. Some quality of life outcomes can suffer from ceiling effects that can result in abolishing the advantage of perfect aligned implants in comparison to those with mild degree of malalignment. The KSS, which is a regularly used functional score and most commonly identified in this review is subject to assessor bias.

Seven studies in this review used CAS. This is relatively small given the popularity of this technique and its consistency at achieving better alignment (Cheng et al. 2012b; Fu et al. 2012; Hetaimish et al. 2012). It would be reasonable to assume that studies reporting CAS outcomes would provide data on the association between alignment and outcome. However, the literature suggest that CAS surgery studies are usually under powered for sub-analysis of aligned versus malaligned and therefore not reported (Khan et al. 2012). Eckhoff et al. assessed CT scans on 90 patients to investigate axial limb alignment. They found that normal individuals expressed a wide range in the straight-line mechanical axis. This has two consequences; if surgical correction of a pathological knee to achieve a straight mechanical axis does not return the mechanical alignment to normal. This can lead to increased pressures on the polyethylene components increasing wear rates. Secondly, if a knee is not straight, the procedures achieve mechanical alignment will alter soft tissue balance affecting PROMs scores. This study has important implications for CAS surgery, if the algorithms do not incorporate this wide variation in natural morphology and kinematics of the knee (as evidenced by Eckhoff) the end result of CAS surgery can lead to further malaligned knees, increased wear and worsening PROMs scores (Eckhoff et al. 2005).

When our results are viewed from the kinematic perspective the unclear association between mechanical alignment and outcome makes sense given that there is a large variation in the anatomy of femora and tibiae and that most patients do not have a neutral hip–knee–ankle axis (Hollister et al. 1993). It is entirely possible that an anatomically (kinematically) aligned, but mechanically malaligned, implanted prosthesis could recreate a patient’s preoperative kinematics. Howell et al. (2015) concluded that kinematic aligned knee replacement did not adversely affect implant survival or function as it restores the constitutional alignment of the limb and joint line, subsequently avoiding collateral ligament imbalances. This would create a group of patients that, for the purposes of the studies included in this review, were “malaligned”, but had good PROMs scores based on their alignment. This could explain the dubious relationship demonstrated between alignment and outcome.

In conclusion, alignment in an individual parameter may have a weak, and perhaps clinically insignificant, effect on scores. However, this evidence is subject to limitations mainly related to the methods of assessing alignment post operatively. Larger longitudinal studies with a standardised, timely, and robust method for assessing alignment outcomes are required.

Authors’ contributions

MH, TB: Literature search, data extraction and production of manuscript. IA: Literature search, data extraction and production of figures and manuscript. MD: Senior author for literature search and production of manuscript. PM: Conception of idea and production of manuscript. DG: Production of manuscript and senior author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional file

10.1186/s40064-016-2790-4 Assessment tool used to assess the radiological criteria used in each study.

Contributor Information

Mohammed Hadi, Email: drmnhadi@gmail.com.

Tim Barlow, Email: Timbarlow1@hotmail.com.

Imran Ahmed, Email: imranahmed08@hotmail.com.

Mark Dunbar, Email: mdunbar@btinternet.com.

Peter McCulloch, Email: Peter.McCulloch@nds.ox.ac.uk.

Damian Griffin, Email: damian.griffin@warwick.ac.uk.

References

- Aglietti P, Lup D, Cuomo P, Baldini A, De Luca L. Total knee arthroplasty using a pie-crusting technique for valgus deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:73–77. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3181591c48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JG, Wixson RL, Tsai D, Stulberg SD, Chang RW. Functional outcome and patient satisfaction in total knee patients over the age of 75. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(7):831–840. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(96)80183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach CM, Mayr E, Liebensteiner M, Gstottner M, Nogler M, Thaler M. Correlation between radiographic assessment and quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2009;16(3):207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J, Gregg PJ. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement: data from the national joint registry for England and wales. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89-B(7):893–900. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankes MJ, Back DL, Cannon SR, Briggs TW. The effect of component malalignment on the clinical and radiological outcome of the Kinemax total knee replacement. Knee. 2003;10(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0160(02)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargren JH, Blaha JD, Freeman MA. Alignment in total knee arthroplasty: correlated biomechanical and clinical observations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;173:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrack RL, Schrader T, Bertot AJ, Wolfe MW, Myers L. Component rotation and anterior knee pain after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:46–55. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SW, Young P, Drury C, et al. Component rotational alignment in unexplained painful primary total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2014;21(1):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berend ME, Ritter MA, Meding JB, et al. Tibial component failure mechanisms in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;428:26–34. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000148578.22729.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeney WG, Khan RJ, Palmer JL. Functional outcomes following total knee arthroplasty: a randomised trial comparing computer-assisted surgery with conventional techniques. Knee. 2014;21(2):364–368. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner TJ, Eardley WG, Patterson P, Gregg PJ. The effect of post-operative mechanical axis alignment on the survival of primary total knee replacements after a follow-up of 15 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(9):1217–1222. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B9.26573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne R, Chesworth B, Davis A, Mahomed N, Charron K. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Drake BG, Heck DA, Dittus RS. Patient outcomes following tricompartmental total knee replacement. JAMA, J Am Med Assoc. 1994;271(17):1349–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510410061034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T, Pan XY, Mao X, Zhang GY, Zhang XL. Little clinical advantage of computer-assisted navigation over conventional instrumentation in primary total knee arthroplasty at early follow-up. Knee. 2012;19(4):237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T, Zhao S, Peng X, Zhang X. Does computer-assisted surgery improve postoperative leg alignment and implant positioning following total knee arthroplasty? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(7):1307–1322. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choong PF, Dowsey MM, Stoney JD. Does accurate anatomical alignment result in better function and quality of life? Comparing conventional and computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(4):560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czurda T, Fennema P, Baumgartner M, Ritschl P. The association between component malalignment and post-operative pain following navigation-assisted total knee arthroplasty: results of a cohort/nested case-control study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(7):863–869. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0990-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhoff DG, Bach JM, Spitzer VM, et al. Three-dimensional mechanics, kinematics, and morphology of the knee viewed in virtual reality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(Suppl 2):71–80. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Schneider M, DaveySmith G. Spurious precision? Meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 1998;316(7125):140–144. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7125.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Wang M, Liu Y, Fu Q. Alignment outcomes in navigated total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(6):1075–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1695-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothesen O, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, et al. Functional outcome and alignment in computer-assisted and conventionally operated total knee replacements: a multicentre parallel-group randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-b(5):609–618. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B5.32516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadi M, Griffin D, Barlow T (2012) The impact of implant malalignment in total knee replacement on patient outcome: a systematic review of the literature. PROSPERO 2012:CRD42012001914. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPER

- Hadi M, Barlow T, Ahmed I, Dunbar M, McCulloch P, Griffin D. Does malalignment affect revision rate in total knee replacements: a systematic review of the literature. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:835. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1604-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetaimish BM, Khan MM, Simunovic N, Al-Harbi HH, Bhandari M, Zalzal PK. Meta-analysis of navigation vs conventional total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollister AM, Jatana S, Singh AK, Sullivan WW, Lupichuk AG. The axes of rotation of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;290:259–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SM, Howell SJ, Kuznik KT, Cohen J, Hull ML. Does a kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty restore function without failure regardless of alignment category? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(3):1000–1007. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2613-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SM, Papadopoulos S, Kuznik KT, Hull ML. Accurate alignment and high function after kinematically aligned TKA performed with generic instruments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(10):2271–2280. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SM, Papadopoulos S, Kuznik K, Ghaly LR, Hull ML. Does varus alignment adversely affect implant survival and function six years after kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty? Int Orthop. 2015;39(11):2117–2124. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2743-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang NF, Dowsey MM, Ee E, Stoney JD, Babazadeh S, Choong PF. Coronal alignment correlates with outcome after total knee arthroplasty: five-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(9):1737–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RL, Saleh KJ, Wilt TJ et al (2003) Total knee replacement: summary. In: AHRQ evidence report summaries, vol 86. Agency for healthcare research and quality (US), Rockville, MD. Publication number 04-E006-1

- Khan MM, Khan MW, Al-Harbi HH, Weening BS, Zalzal PK. Assessing short-term functional outcomes and knee alignment of computer-assisted navigated total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Chang CB, Kang YG, Kim SJ, Seong SC. Causes and predictors of patient’s dissatisfaction after uncomplicated total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(2):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstaff LM, Sloan K, Stamp N, Scaddan M, Beaver R. Good alignment after total knee arthroplasty leads to faster rehabilitation and better function. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(4):570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotke PA, Ecker ML. Influence of positioning of prosthesis in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(1):77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzner J, Gunther KP, Kirschner S. Functional outcome after computer-assisted versus conventional total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(10):1339–1344. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnussen RA, Weppe F, Demey G, Servien E, Lustig S. Residual varus alignment does not compromise results of TKAs in patients with preoperative varus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(12):3443–3450. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1988-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March LM, Cross MJ, Lapsley H, et al. Outcomes after hip or knee replacement surgery for osteoarthritis. A prospective cohort study comparing patients’ quality of life before and after surgery with age-related population norms. Med J Aust. 1999;171(5):235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matziolis G, Adam J, Perka C. Varus malalignment has no influence on clinical outcome in midterm follow-up after total knee replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(12):1487–1491. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland JR. Mechanisms of failure in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;226:49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll D, Rowley DI. Internal rotational error of the tibial component is a major cause of pain after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(9):1238–1244. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.23516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parratte S, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Effect of postoperative mechanical axis alignment on the fifteen-year survival of modern, cemented total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(12):2143–2149. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Registry NJ (2013) National joint Registry 11th Annual report. http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/Portals/0/Documents/England/Reports/11th_annual_report/NJR 11th AR Prostheses used in hip, knee, ankle, elbow and shoulder replacements 2013.pdf

- Rienmuller A, Guggi T, Gruber G, Preiss S, Drobny T. The effect of femoral component rotation on the five-year outcome of cemented mobile bearing total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2012;36(10):2067–2072. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter MA, Faris PM, Keating EM, Meding JB. Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement. Its effect on survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter MA, Davis KE, Meding JB, Pierson JL, Berend ME, Malinzak RA. The effect of alignment and BMI on failure of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(17):1588–1596. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Dunbar M, Pehrsson T, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Patient satisfaction after knee arthroplasty: a report on 27,372 knees operated on between 1981 and 1995 in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(3):262–267. doi: 10.1080/000164700317411852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CEH, Howie CR, MacDonald D, Biant LC. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a prospective study of 1217 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92-B(9-B):1253–1258. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.24394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski JM. Alignment in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(9):1121–1127. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B9.20793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulberg SD, Yaffe MA, Shah RR, et al. Columbus primary total knee replacement: a 2- to 4-year followup of the use of intraoperative navigation-derived data to predict pre and postoperative function. Orthopedics. 2008;31(10 Suppl 1):51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tew M, Waugh W. Tibiofemoral alignment and the results of knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67(4):551–556. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B4.4030849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Essen GJ, Chipchase LS, O’Connor D, Krishnan J. Primary total knee replacement: short-term outcomes in an Australian population. J Qual Clin Pract. 1998;18(2):135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ansari MT, Berkman ND, et al. Assessing the risk of bias of individual studies in systematic reviews of health care interventions. Rockville: Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ansari MT, Berkman ND, et al. AHRQ methods for effective health care assessing the risk of bias of individual studies in systematic reviews of health care interventions. Rockville: Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner FW, Ayers DC, Maletsky LP, Rullkoetter PJ. The effect of valgus/varus malalignment on load distribution in total knee replacements. J Biomech. 2005;38(2):349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]