Abstract

Background

A median progression free survival (PFS) of 18–20 months and median overall survival (OS) of 51–57 months can be achieved with the use of imatinib, in metastatic or advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Sunitinib and regorafenib are approved options for patients progressing on imatinib, but with markedly decreased survival. pazopanib is a broad spectrum TKI targeting KIT, PDGFR and VEGFR receptors and has shown promising activity in phase 2 trials in GIST.

Methods

All patients who received pazopanib for GIST between March 2014 and September 2015 in our institution were reviewed. Patients were assessed for response with CT or PET CT scans. Patients continued pazopanib until progression or unacceptable toxicity. Survival was evaluated by Kaplan Meier product method.

Results

A total of 11 consecutive patients were included in our study. Median duration of follow up was seven months. The median lines of prior therapy was 2 [1-5]. Partial response (PR) was observed in seven patients and two had stable disease (SD). Two patients died within one month of start of pazopanib. Five of ten patients had progressed during the study with eight patients still alive. The median PFS was 11.9 months and the median OS was not reached. Common adverse events seen were hand-foot-syndrome (HFS) in four patients, anemia in four patients and fatigue in three patients. Grade 3/4 adverse events were uncommon. Three patients required dose modification of pazopanib.

Conclusions

Pazopanib is a reasonably efficacious well tolerated TKI and can be explored as a treatment option in advanced GIST that has progressed on imatinib.

Keywords: Metastatic GIST, pazopanib

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) accounts for 1% of primary GI tumors and can arise from any part of GI tract. Their clinical presentation is varied with respect to site, size and rapidity of growth (1,2).

More than half of the new cases of GIST present with advanced or metastatic disease at presentation. Beginning with a single patient of metastatic GIST treated on a pilot study basis with imatinib mesylate (IM) (3), multiple studies confirmed the remarkable benefit and survival of patients with advanced GIST on IM (4-6). Further advances have led to the approval of 2nd generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), like sunitinib (7,8) and regorafenib (9) for progressive GIST, with the option of rechallenge with a higher dose (HI) of IM also feasible as a short-term measure.

Pazopanib is an oral small molecule multikinase inhibitor, targeting KIT, VEGFR (1, 2, and 3) and PDGFR (alpha and beta). Commonly used in RCC (10) and soft tissue sarcomas (11), little was known of its activity against wild type KIT or drug resistant KIT mutations. However, a large phase 2 trial, PAZOGIST, and an earlier, smaller one by Ganjoo et al., evaluated the role of pazopanib in progressive GIST (post prior IM and sunitinib) and found a PFS benefit on comparison with best supportive care alone (12,13).

In this study, we present the efficacy and safety data of 11 patients with metastatic, unresectable GIST treated with pazopanib after progression on multiple lines of therapy in our institution. The primary aim was to document its performance in clinical practise in a tertiary academic centre.

Methods

Patient with advanced, unresectable or metastatic GIST from a prospectively maintained GIST database, who had received pazopanib between March 2014 and September 2015 were included in this analysis. Baseline demographic variables, comorbidities, prior treatment received, KIT/PDGFR mutation status and prior surgery if done was retrieved from electronic records. IM, administered as HI on progression with standard dose IM, was considered a further line of therapy for analysis.

Pretreatment evaluation

Physical examination and routine blood testing (complete hemogram, renal and liver function tests) was done as part of standard work-up. Specific tests required prior to administration of pazopanib, including cardiac evaluation with ECG and 2 D Echo, urine for proteinuria and Thyroid function tests was done for all patients. Patients were restaged by contrast enhanced CT scan or PET CT prior to starting pazopanib as part of documenting progressive disease.

Treatment and follow up

All patients were started on 600 mg once daily dose and then escalated to full 800 mg once daily dosing over a period of 2–4 weeks once tolerance was established. Dose decrements were based on toxicity.

As part of institution protocol for patients on TKIs, Complete Hemogram and Liver function tests was repeated biweekly for two visits and then monthly. ECG, 2 D echo, urine routine and thyroid function tests were performed every three months. Toxicity was assessed on every visit and graded as per CTCAE version 4.0. Response to treatment was evaluated by CT or PET-CT every three months and reported as per RECIST 1.1.

Statistical analysis

Response rates including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD) were calculated.

Progression free survival (PFS) was calculated from date of 1st dose of pazopanib to date of first documented progression or death. Overall survival (OS) was defined as time from first dose of pazopanib to death from any cause or last date of documented follow up. PFS and OS was calculated by Kaplan Meier product limit method.

Results

Pre-treatment characteristics

A total of 11 patients from March 2014 to September 2015 were started on pazopanib and were included in this analysis (Table 1). The median age of this cohort was 45 years, with 10 males and 1 female. Gastric subsite was the commonest, seen in six patients followed by small bowel in four patients and one patient with retroperitoneal primary. Seven patients had undergone prior surgery. Exon 11 was the commonest c-kit mutation, seen in three patients, with exon 9 and exon 17 in one patient respectively. Two patients had PDFRA mutations (one patient had a mutation in exon 12 and exon 18). Mutation status was not interpretable in three patients and unavailable in one patient.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Baseline characteristics | N |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 11 |

| Median age, years (range) | 45 [36-65] |

| Median ECOG PS (range) | 1 (0-2) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 |

| Female | 1 |

| Median lines of prior therapy | 2 [1-5] |

| Prior high dose Imatinib | 8 |

| Prior sunitinib | 5 |

| Prior everolimus | 2 |

| Sites of disease | |

| Primary site | |

| Gastric | 6 |

| Small bowel | 4 |

| Retroperitoneal | 1 |

| Metastatic site | |

| Liver | 6 |

| Nodes | 6 |

| Peritoneal | 5 |

| Lung | 1 |

| Prior surgery | |

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 4 |

| Mutation status | |

| c-kit | |

| Exon 11 | 3 |

| Exon 9 | 1 |

| Exon 17 | 1 |

| PDGFRA | |

| Exon 18 | 2 |

| Exon 12 | 1 |

| Uninterpretable | 3 |

| Unavailable | 1 |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; PDGFRA, platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha.

Patients had received a median of 2 lines of previous treatment, as shown in Tables 2,3. Eight patients had received HI as second line therapy, while 5 patients had received sunitinib at some point of time prior to pazopanib. Other pre-treatment variables are shown in Tables 1,3.

Table 2. Response rates and survival.

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Median follow up (months) | 7 |

| Response | |

| PR | 7 (63.6) |

| SD | 2 (18.1) |

| PD | 2 (18.1) |

| Median PFS (months) | 11.92 |

| Median OS | Not reached |

| 1 yr PFS | 26.8 |

| 1 yr OS | 71.6 |

PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression free survival; OS, overall survival.

Table 3. Selected characteristics of all 11 patients on pazopanib (P).

| Serial number | Primary site | Mutation status | Prior treatment | PFS on P (months) | Current status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Retroperitoneal | c-kit exon 9 | IM, HI | 18 | Alive, on P |

| 2 | Gastric | PDFRA exon 12 & exon 18 | IM | 1 | Rapidly progressive, died in 1 month |

| 3 | Gastric | c-kit exon 11 | IM, S, N, E | 5 | Progressed, died |

| 4 | Gastric | c-kit exon 11 | IM, HI, S | 7 | Progressed, alive on R |

| 5 | Small bowel | c-kit exon 11 | IM,HI,S, So, E | 11 | Progressed, alive on R |

| 6 | Gastric | Uninterpretable | IM, HI | 5 | Alive, on P |

| 7 | Gastric | Uninterpretable | IM, HI | 10 | Alive, on P |

| 8 | Small bowel | NA | IM, HI, S | 5 | Alive on P |

| 9 | Small bowel | Uninterpretable | IM, HI | 4 | Alive on P |

| 10 | Small bowel | c-kit exon 17 | IM, S | 6 | Alive on P |

| 11 | Gastric | PDGFRA exon 18 | IM, HI | 1 | Rapidly progressive, died in 1 month |

P, pazopanib; IM, imatinib; HI, high dose imatinib; S, sunitinib; So, sorafenib; N, nilotinib; E, everolimus plus imatinib; R, regorafenib.

Survival and adverse events

After a median follow up of seven months, 7 patients (63.6%) had achieved a best response of PR while 2 patients (18.1%) had SD. Two patients died at 4 and 5 weeks respectively of starting pazopanib and were considered as PD (Table 2).

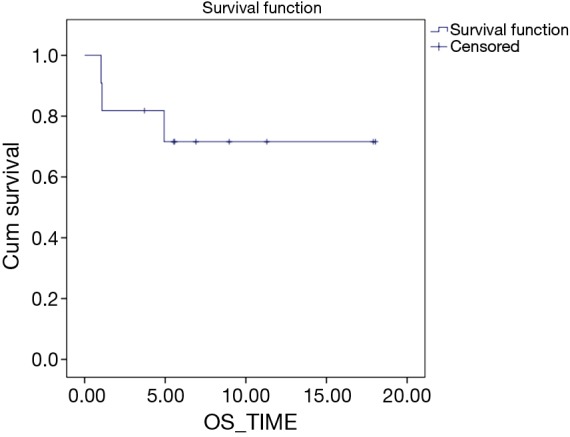

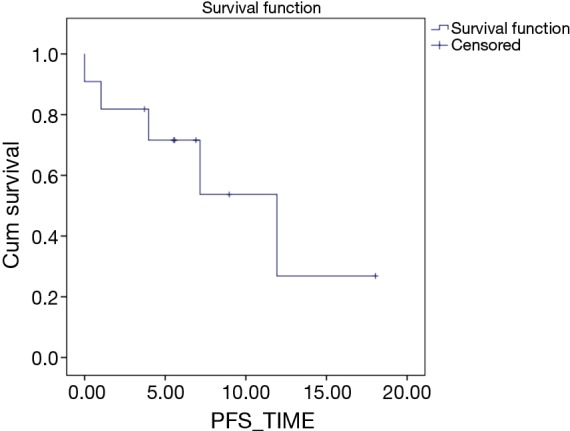

Median PFS was 11.92 months while median OS was not reached. Estimated 1 year PFS was 26.8% while estimated 1 yr. OS was 71.6% (Figures 1,2). Till date of analysis, eight patients were alive with six of them continued on pazopanib, while two patients were on further treatment with regorafenib after progression of pazopanib. Two patients, as previously mentioned, died early on treatment, while one patient died of progressive disease after a PFS of 5 months.

Figure 1.

Overall survival Kaplan Meier curve.

Figure 2.

Progression free survival Kaplan Meier curve.

The grade 3/4 adverse effects seen were anemia in 2 patients (22%), hand-foot-syndrome (HFS) and fatigue in 1 patient each (11%), respectively. New onset hypertension or worsening of pre-existing hypertension requiring escalation of medications and proteinuria were seen in 2 patients (22%). Dose reduction was required in 3 patients (33%), because of HFS or fatigue or a combination of both (Table 4).

Table 4. Adverse events.

| Adverse event | Grade 1/2 [%] | Grade 3/4 [%] | All grades [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| HFS | 3 [33] | 1 [11] | 4 [44] |

| Transamintis | 2 [22] | – | 2 [22] |

| Fatigue | 2 [22] | 1 [11] | 3 [33] |

| Diarrhoea | 1 [11] | – | 1 [11] |

| Proteinuria | 2 [22] | – | 2 [22] |

| Anemia | 2 [22] | 2 [11] | 4 [44] |

| Hypertension | 2 [22] | 2 [22] | |

| Dose modifications | |||

| Yes | 3 [33] | ||

| No | 8 [67] | ||

| Reason for modification | |||

| HFS | 2 | ||

| Fatigue | 3 |

HFS, hand-foot-syndrome.

Discussion

IM has transformed the landscape of treatment of GIST and currently, continuous, uninterrupted IM is the recommended first line treatment for advanced/metastatic GIST. Median OS is in the range of 51–57 months with a median PFS of 18–20 months (4-6,14). With this has also come the realization that increased survival, however, does not equate with cure. 80–90% of patients will eventually progress on IM and the approved agents for 2nd and 3rd line, sunitinib and regorafenib, offer markedly reduced survival in comparison to IM (7,9). Indeed, a metanalysis, albeit of only 3 trials, concluded provocatively that 2nd generation TKI’s showed only PFS benefit and no OS benefit on comparison to controls (i.e., Placebo) (15). This, combined with issues of tolerance with these drugs, have encouraged further research in this area.

A number of TKI’s (16,17) and non TKI molecules (18,19) have been evaluated for the treatment of GIST progressing on IM. One of them, is pazopanib, which is a potent VEGFR, PDGFR and kit inhibitor. Ganjoo et al. in a small phase trial (13) showed that pazopanib was a well tolerated TKI with potential in progressive GIST with median PFS of 1.9 months and median OS of 10.7 months. One of the reasons quoted for the low PFS was the heavily pre-treated nature and possible lack of c-kit inhibition in patients in the study. The PAZOGIST study (12) also indirectly showed a similar PFS though, there were a high number of adverse events with 72.4% patients experiencing grade 3 or 4 adverse events.

Our series of 11 patients who received pazopanib provides an early insight into experience with this drug in advanced, progressive GIST. Unlike the published phase 2 studies, only five patients in this series had received sunitinib previously, while seven had received high dose imatinib. The major reason for the decreased use of sunitinib is the prohibitive cost in our setup, when compared to imatinib and pazopanib. The patients who have progressive disease on HI of imatinib, are generally nutritionally poor with low serum albumin and have higher possibility of not tolerating sunitinib well. A high number of prior surgeries in the curative setting, coupled with lesser number of prior median treatments compared to published phase 2 data, resulted in markedly better median PFS of 11.92 months in our study with a median OS not reached. This PFS is also higher than that obtained with IM rechallenge, which shows a median PFS of 1.8 months (20). While a majority of the benefit in second line treatment of GIST results in disease stabilization, we saw a PR in 7 patients (63.6%), albeit as per RECIST, which is very high. One of the patients with a c-kit exon 9 mutation had completed 18 months of pazopanib and was still on treatment. While it is a single patient, it mirrors the experience with sunitinib in patients with primary c-kit exon 9 mutation, where clinical benefit as well survival was improved in patients compared to those with primary exon 11 mutation or wild type (21). Whether this is because of the greater potency of pazopanib against Tyrosine kinases in certain mutations, as has been observed in in vitro studies with imatinib (22), remains to be seen. Both patients with PDGFRA exon 18 mutations died within a month of starting pazopanib, reiterating the difficult to treat nature of these tumors.

The reason we consider early use of pazopanib in our patients is its better safety profile and cost effectiveness in comparison to sunitinib. A strategy of starting at a lower dose of pazopanib, i.e., 600 mg, while unproven, also enables us to assess tolerance before dose escalation. The adverse event profile, due to the retrospective nature of the study, has a bias towards greater reporting of Grade 3/4 events. With this caveat, pazopanib seemed well tolerated. The commonest clinically relevant side effects were HFS and fatigue, which are as expected, with three patients requiring dose reduction. Hypertension, a purported marker of efficacy and anti-VEGF action, was seen in only two patients. While the side-effects are lesser than what is reported in GIST, it is line with data regarding the use of pazopanib in RCC, where quality of life and side effect profile of pazopanib were superior to sunitinib (23).

In conclusion, in our series, pazopanib seems to have good activity against IM resistant GIST with a good safety profile. This, coupled with its cost effectiveness in our setup, argues for a greater evaluation of pazopanib in second line treatment of GIST, with further evaluation into its differential activity against various genotypes.

Acknowledgements

None.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by institutional ethics committee/ethics board (No. IEC/0815/1524/001).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:1466-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol 2002;33:459-65. 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joensuu H, Roberts PJ, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in a patient with a metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1052-6. 10.1056/NEJM200104053441404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med 2002;347:472-80. 10.1056/NEJMoa020461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verweij J, van Oosterom A, Blay JY, et al. Imatinib mesylate (STI-571 Glivec, Gleevec) is an active agent for gastrointestinal stromal tumours, but does not yield responses in other soft-tissue sarcomas that are unselected for a molecular target. Results from an EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group phase II study. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:2006-11. 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00836-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanke CD, Demetri GD, von Mehren M, et al. Long-term results from a randomized phase II trial of standard- versus higher-dose imatinib mesylate for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing KIT. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:620-5. 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006;368:1329-38. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George S, Blay JY, Casali PG, et al. Clinical evaluation of continuous daily dosing of sunitinib malate in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after imatinib failure. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1959-68. 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demetri GD, Reichardt P, Kang YK, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:295-302. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61857-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, Szczylik C, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2010. Feb 20;28:1061-8. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012;379:1879-86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blay JY, Molimard M, Cropet C, et al. Final results of the multicenter randomized phase II PAZOGIST trial evaluating the efficacy of pazopanib (P) plus best supportive care (BSC) vs BSC alone in resistant unresectable metastatic and/or locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). J Clin Oncol 2015;33:abstr 10506.

- 13.Ganjoo KN, Villalobos VM, Kamaya A, et al. A multicenter phase II study of pazopanib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) following failure of at least imatinib and sunitinib. Ann Oncol 2014;25:236-40. 10.1093/annonc/mdt484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blay JY, Le Cesne A, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Prospective multicentric randomized phase III study of imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors comparing interruption versus continuation of treatment beyond 1 year: the French Sarcoma Group. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1107-13. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu L, Zhang Z, Yao H, et al. Clinical efficacy of second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a meta-analysis of recent clinical trials. Drug Des Devel Ther 2014;8:2061-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reichardt P, Blay JY, Gelderblom H, et al. Phase III study of nilotinib versus best supportive care with or without a TKI in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors resistant to or intolerant of imatinib and sunitinib. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1680-7. 10.1093/annonc/mdr598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang YK, Yoo C, Ryoo BY, et al. Phase II study of dovitinib in patients with metastatic and/or unresectable gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib. Br J Cancer 2013;109:2309-15. 10.1038/bjc.2013.594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schöffski P, Reichardt P, Blay JY, et al. A phase I-II study of everolimus (RAD001) in combination with imatinib in patients with imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1990-8. 10.1093/annonc/mdq076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer S, Hilger RA, Mühlenberg T, et al. Phase I study of panobinostat and imatinib in patients with treatment-refractory metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Br J Cancer 2014;110:1155-62. 10.1038/bjc.2013.826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang YK, Ryu MH, Yoo C, et al. Resumption of imatinib to control metastatic or unresectable gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (RIGHT): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1175-82. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70453-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinrich MC, Maki RG, Corless CL, et al. Primary and secondary kinase genotypes correlate with the biological and clinical activity of sunitinib in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5352-9. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo T, Agaram NP, Wong GC, et al. Sorafenib inhibits the imatinib-resistant KITT670I gatekeeper mutation in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:4874-81. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:722-31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1303989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]