Summary

Objective

Valnoctamide (VCD), a CNS-active chiral constitutional isomer of valpromide the corresponding amide of valproic acid (VPA), is currently undergoing phase IIb clinical trial in acute mania. VCD exhibits stereoselective pharmacokinetics (PK) in animals and humans. The current study comparatively evaluated the pharmacodynamics (PD; anticonvulsant activity and teratogenicity) and PK of VCD four individual stereoisomers.

Methods

The anticonvulsant activity of VCD individual stereoisomers was evaluated in several rodent anticonvulsant models including: maximal electroshock, 6Hz psychomotor, subcutaneous metrazol and the pilocarpine- and soman-induced status epilepticus (SE). The PK-PD (anticonvulsant activity) relationship of VCD stereoisomers was evaluated following ip administration (70mg/kg) to rats. Induction of neural tube defects (NTDs) by VCD stereoisomers was evaluated in a mouse strain highly-susceptible to teratogen-induced neural tube defects.

Results

VCD had a stereoselective PK with (2S,3S)-VCD exhibiting the lowest clearance and consequently, a twice-higher plasma exposure than all other stereoisomers. Nerveless, there was less stereoselectivity in VCD anticonvulsant activity and each stereoisomer had similar ED50 values in most models. VCD stereoisomers (258 or 389 mg/kg) did not cause NTD. These doses are 3–12 times higher than VCD anticonvulsant-ED50 values.

Significance

VCD displayed stereoselective PK that did not lead to significant stereoselective activity in various anticonvulsant rodent models. If VCD exerted its broad-spectrum anticonvulsant activity using a single mechanism of action (MOA) it is likely that it would exhibit a stereoselective PD. The fact that there was no significant difference between racemic-VCD and its individual stereoisomers, suggests that VCD's anticonvulsant activity is due to multiple MOA.

Keywords: New Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), CNS drugs, Strereoselective Pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) analysis, Chiral switch

Introduction

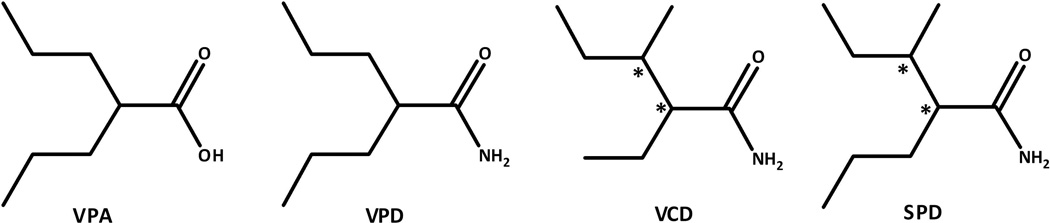

Valnoctamide (VCD; Fig. 1) is a CNS-active chiral constitutional isomer of valpromide (VPD; Fig. 1), the corresponding amide of valproic acid (VPA) that exhibits stereoselective pharmacokinetics in animals and humans.1–3 Unlike VPD that acts as a prodrug to VPA in humans, VCD acts as a drug on its own with minimal biotransformation to its corresponding acid valnoctic acid (VCA).1,4–5 VCD (racemate) was commercially available as an anxiolytic drug (Nirvanil®) in several European countries from 1964 until as recently as 2005.2,3,6 Two suicide attempts with VCD overdose led patients into coma, however in spite of the significantly elevated VCD serum level the patients survived without adverse consequences and recovery was rapid and complete..7,8 VCD half-life (t1/2) in this overdose case (15 h) was similar to its clinically-relevant t1/2 of 7–13h.4,5 These two suicide attempts show that racemic-VCD is a safe compound even at high doses.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of Valproic Acid (VPA), Valpromide (VPD), Valnoctamide (VCD) and sec-butyl-propylacetamide (SPD).

VCD possesses two chiral (stereogenic) centers in its chemical structure (Supporting Information, Fig. 1). Racemic-VCD has a wide spectrum of anticonvulsant activity and its ED50 values that are 2–16 times (depending on the model) more potent than those of VPA.2 VCD (65 mg/kg, ip) also provided full protection in the pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus (SE) rat model when administered at seizure onset. However in contrast to its one-carbon homologue sec-butyl-propylacetamide (SPD), VCD lost its behavioral SE protection when administered (80 mg/kg) 30 min after seizure onset,9 but it did block pilocarpine-induced electrographic SE at a higher dose (180 mg/kg).10

Racemic-VCD, its corresponding acid VCA and two of its individual stereoisomers (2R,3S)-VCD and (2S,3S)-VCD all failed to exert any significant teratogenic effect in SWV/Finn mice. This is an inbred mouse strain that has previously been shown to be highly susceptible to VPA-induced teratogenicity, following a single dose (600 mg/kg, ip) at day 8.5 of gestation.11–12 VCD also inhibited human brain myo-inositol-1-phosphate (MIP) synthase at VPA clinically-relevant concentrations (0.5–1mM), indicating its potential in bipolar disorder.13 Recently, a successful double-blind controlled Phase IIa clinical trial with racemic-VCD was completed in patients with mania was completed.14–15 This study showed that VCD could be an important substitute to VPA in women of child-bearing age with bipolar disorder.

Following a successful phase IIa study in patients with mania funded by the Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI),14 teratogenicity studies were conducted (by the SMRI) comparing racemic-VCD to VPA (head-to head) in mice, rats and rabbits at Covance Laboratories. In these additional studies, VCD in contrast to VPA failed to demonstrate teratogenic potential in mice and rabbits. In rats a modest teratogenic signal was observed at plasma concentrations 15-times higher than VCD therapeutic plasma levels.16 Consequently, VCD is currently undergoing a 3-week SMRI-funded Phase IIb, randomized double-blind multicenter study in 300 patients with bipolar manic episodes. The study is a 3-arm monotherapy parallel group trial in which patients are randomized to placebo (n=120), VCD 1500 mg/day (n=120) and risperidone, up to 6 mg/day (n=60). The study’s major objective is to evaluate the efficacy of VCD compared to placebo in patients with acute manic or mixed episodes. Risperidone is included as an active control to ascertain the trial’s assay validity.16

All studies so far investigated racemic-VCD and two of its four individual stereoisomers (2S,3S)-VCD and (2R,3S)-VCD). The current study comparatively investigates the anticonvulsant activity, teratogenicity and pharmacokinetics of the two remaining VCD strereoisomers; (2S,3R)-VCD and (2R,3R)-VCD. The study also aims to pin point the most potent VCD individual stereoisomer and to explore if an individual stereoisomer might to be better than racemic-VCD and thus serves after a chiral switch as its follow-up compound.17–18

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagent and Animals

See Supporting Information.

Effect of VCD stereoisomers on lithium-pilocarpine-induced SE

Seizures were induced by systemic administration of pilocarpine HCl (50 mg/kg; i.p.),. LiCl (20 mg/kg; i.p.) was administered 24 hr prior to the pilocarpine dosing. Pilocarpine induces behavioral seizures within a few minutes and those animals showing no seizures after 45 min of pilocarpine were removed from the study. At the time of the first stage 3 or higher (Racine scale) seizure, rats were randomized into two groups, pilocarpine alone or pilocarpine + an individual VCD stereoisomer. The latter group received the individual VCD stereoisomer or the racemate at 0 min or 30 minutes after the first stage 3 seizure. Animals were observed and scored for seizure severity for 1.5 hr before being returned to their home cages. All animals were given 1 ml of 0.9% saline (oral) to compensate for the fluid loss induced by excessive cholinergic activation. Each VCD stereoisomer was dissolved in multisol; a solution of propylene glycol, alcohol and water for injection 5:1:4.

The median effective dose (ED50) for anticonvulsant activity for the various VCD stereoisomers was determined by probit analysis.19

Effect of VCD on soman-induced SE

An established rodent models of nerve agent-induced SE were used; a rat HI-6 pretreatment model.20–21 The model utilized a pretreatment and adjunctive drugs that counters the acute immediate lethal effects of the nerve agent without inhibiting the development of SE. In this models the challenge dose of soman is sufficient to elicit SE in all animals 5–8 min following soman challenge.

Subjects: Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Crl:DCBR VAF/Plus) from Charles River Labs, weighing 250–300 g upon receipt, served as subjects. The animals were housed individually in temperature (21± 2 °C) and humidity (50 ± 10%) controlled quarters and maintained on a 12-h light-dark full spectrum lighting cycle with lights on at 0600. Laboratory rat chow and tap water were freely available.

Each animal was anesthetized with isoflorane (5% induction; 3–1.5% maintenance, with oxygen) and placed in a stereotaxic instrument. Two stainless steel screws were placed in the skull bilaterally midway between bregma and lamda and ~3 mm lateral to the midline. A third screw was placed over the cerebellum. The screws were connected to a miniature connector with wires and the screws, wires and connector were then anchored to the skull with dental cement. The incision was sutured; the animal was removed from the frame, given the analgesic buprenorphine HCl (0.03 mg/kg, SC) and placed on a warming pad for at least 30 min before being returned to the animal quarters. Approximately seven days elapsed between surgery and experimentation.

The animals were typically tested in groups of eight and were randomized among treatment cohorts each test day. The animals were weighed, placed in individual recording chambers and connected to the recording apparatus. EEG signals were recorded using CDE 1902 amplifiers and displayed on a computer running Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Baseline EEG was recorded for at least 20 min. The animals were then pretreated with 125 mg/kg, i.p., of the oxime HI-6 to prevent the rapid lethal effects of the soman challenge. Thirty min after pretreatment the rats were challenged with 180 µg/kg, s.c, soman (1.6 × LD50) and 1 min later treated with 2.0 mg/kg, i.m., atropine methyl nitrate to inhibit peripheral secretions. The rats were then closely monitored both visually and on the EEG for seizure onset. Seizure onset was operationally defined as the appearance of >10sec of continuous rhythmic high amplitude spikes or sharp waves that were at least twice the baseline amplitude accompanied by a rhythmic bilateral flicking of the ears, facial clonus and possibly forepaw clonus. The rats received standard medical countermeasures [0.1 mg/kg atropine sulfate + 25 mg/kg 2-PAM Cl admixed to deliver 0.5 mL/kg, i.m., and 0.4 mg/kg im diazepam] at 5, 20 or 40 min after seizure onset and then were immediately given a dose (10 –165 mg/kg) i.p, of VCD dissolved in multisol (a solution of propylene glycol, alcohol and water for injection 5:1:4). These standard medical countermeasures (atropine, 2-PAM, and in the rat model, diazepam), at the doses and times used, are insufficient by themselves to terminate soman-induced seizures in this model. The rats were monitored for at least 5 h after exposure and then returned to the animal housing room. Twenty-four hr after the exposure, surviving animals were weighed and the EEG again recorded for at least 30 min. Evaluation and categorization of the EEG response by an individual animal to treatment were performed by a technician and investigator, both well-experienced with the appearance of nerve agent-induced EEG seizure activity. The overall rating and timing of different events required consensus between both individuals, who were aware of the treatment conditions of an individual animal. To be rated as having the seizure terminated, all spiking and/or rhythmic waves had to stop and the EEG had to remain normal for at least 60 min. For each animal in which the seizure was terminated, the latency to seizure termination was measured as the time from when the animal received VCD to the last observable epileptiform event in the EEG.

Teratogenic Investigations of Susceptibility to the Induction of Neural Tube Defect (NTD)

For this study, the highly inbred SWV/Fnn mouse strain with a known susceptibility to AED-induced NTDs12,22 was used, according to the previously published procedure.22 Dams were allowed to mate overnight with male mice, and were examined on the following morning for the presence of vaginal plugs. The onset of gestation was set at 10 p.m. of the previous night. On gestational day 8.5, pregnant females received a single ip injection (10µL per gram body weight) of sodium valproate at doses 2.7 or 1.8 mmol/kg, or VCD (racemate or its individual stereoisomers) at equimolar doses of 2.7 or 1.8. mmol/kg. A 25% Cremophor EL water solution was injected ip to dams constituting the control group. On gestation day 8.5, the dams were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation, the abdomen opened and the gravid uteri removed. The locations of all viable, dead and resorbed fetuses were recorded, and the fetuses were grossly examined for the presence of exencephaly.

Pharmacokinetic studies

Analysis of VCD stereoisomers in plasma and Calculation of pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters

See Supporting Information.

Results

Chemistry

The general synthesis of VCD two individual stereoisomers (2R,3R)-VCD and (2S,3R)-VCD is depicted in Supporting Information-Scheme 1 and detailed in the Supporting Information. The synthesized products were purified by crystallization. 1H NMR spectra of the synthesized compounds were measured in DMSO using TMS as an internal standard. Elemental analyses were performed for all the synthesized compounds.

Time to peak effects (TPE) of VCD stereoisomers and Determination of their Median Effective (ED50) or Behavioral Toxic Dose (TD50)

All quantitative in vivo anticonvulsant/behavioral toxicity studies were conducted at time to peak effect (TPE) previously determined in a qualitative analysis. The TPE of VCD strereoisomers was 0.25–0.5h and 0.5–2h following ip and oral administration, respectively. Groups of 4–8 mice or rats were tested with various VCD stereoisomers' doses until at least two points were established between the limits of 100% protection or minimal toxicity and 0% protection or minimal toxicity. The dose of drug required to produce the desired endpoint in 50% of animals (ED50 or TD50) in each test, the 95% confidence interval, the slope of the regression line, and the SEM of the slope were then calculated by a computer program based on the method described by Finney.23

Anticonvulsant Efficacy of VCD stereoisomers in Seizure and Epilepsy Rodents Models

The anticonvulsant activity of the individual VCD stereoisomers (in comparison to racemic-VCD) is depicted in Tables 1. In mice the four VCD individual stereoisomers exhibited similar anticonvulsant activity to one another as well as to racemic-VCD in the scMet and 6Hz tests, while at the MES test (2R,3R)-VCD was more potent than its enantiomer (2S,3S)-VCD and diastereoisomer (2S,3R)-VCD. In rats (po) racemic-VCD and its four individual stereoisomers exhibited similar anticonvulsant activity in the MES test while (2R,3S)-VCD was the most portent compound evaluated by the scMet test with an ED50 value 5-times more potent than the racemate.

Table 1.

Anticonvulsant activity and neurotoxicity of VCD (racemate) and its four individual stereoisomers following ip administration to mice and ip or oral administration to rats

| Anticonvulsant Test | ED50 (95% coinfidence interval) (mg/kg) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCD (racemate) | (2R,3S)-VCD | (2S,3S)-VCD | (2S,3R)-VCD | (2R,3R)-VCD | ||

| Mice-ip administration | Maximal electroshock seizure (MES) |

125 (102–143) | 119 (98–147) | 132 (117–149) | 144 (138–151) | 105 (101–112) |

| Metrazol-induced seizure (scMet) |

66 (50–74) | 67 (60–74) | 69 (63–72) | 79 (63–94) | 71 (63–81) | |

| 6 Hz – 22mA | 19 (15–25) | 25 (15–40) | ||||

| 6 Hz – 32mA | 37 (26–50) | 48 (32–62) | 33 (23–45) | 40 (27–60) | 59 (36–81) | |

| 6 Hz – 44mA | 67 (61–72) | 67 (54–79) | 80 (62–105) | 64 (58–74) | ||

| Neurotoxicity (TD50) |

164 (149–180) | 127 (113–143) | 128 (108–155) | 170 (164–176) 152 (0.25 hr) |

143 (129–164) 164 (164–186) |

|

| Rats-ip administration | Pilocarpine-induced status (0min) |

40 (30–65) ED97=86 (55–214) |

39 (31–80) ED97=59 (48–131) |

<65 | ||

| Pilocarpine-induced status (30min) |

No protection at 80mg/kg |

No protection at 75mg/kg |

No protection at 75mg/kg |

No protection at 100 mg/kg |

||

| Maximal electroshock seizure (MES) |

29 (19–38) | 34 (14–79) | 64 (43–90) | 95 (56–163) | 48 (29–87) | |

| Metrazol-induced seizure (scMet) |

54 (46–63) | 11 (4–28) | 33 (28–39) | 27 (16–40) | 41 (29–53) | |

| Neurotoxicity (TD50) | 58 (47–66) | 123 (102–234) | 194 (165–239) | 92 (79–104) | 75 (57–96) | |

VCD stereoisomers block convulsive seizures induced by cholinergic agonist, pilocarpine

Administration of lithium-pilocarpine induces SE characterized by convulsive and non-convulsive seizures that can last for several hours. From a behavioral perspective, the number and severity of the observed convulsive seizures following pilocarpine administration were similar in the two treatment groups (pilocarpine alone and pilocarpine + VCD racemate/stereoisomer). The first convulsive Stage 3 (marking the SE onset) or greater seizure was observed 12 min after pilocarpine administration and lasted for approximately 60 sec. Within the succeeding 30 minutes, rats were observed to have 4.9±0.2 seizures with an inter-seizure interval of 3–5 minutes.9 Racemic-VCD as well as (2R,3S)-VCD and (2S,3S)-VCD, administered at seizure onset blocked the SE with similar ED50 values of about 40 mg/kg. However racemic-VCD and three of its individual strereoisomers lost this anti-SE activity when given (75–100 mg/kg) 30 min after seizure onset (Table 1).

VCD blocks electrographic and convulsive seizures induced by the organophosphate soman

Racemic-VCD dissolved in multisol was administered at various doses along with the standard medical countermeasures at treatment delays of 5, 20 and 40 min after the onset of soman-induced seizures to determine effective dose for termination of electrographic seizures as described previously for racemic-SPD.9 Racemic-VCD (dissolved in multisol) administered with the standard medical countermeasures at treatment delays of 5 min, 20 min and 40 min after seizure onset was capable of stopping soman-induced SE seizures with ED50 values of 26mg/kg, 60mg/kg and 62mg/kg, respectively (Fig. 2). Following administration of VCD the average latency (sec) for electrographic seizure termination (mean±SEM) at 5 min, 20 min and 40 min was: 115±15, 497±15 and 1,336±318, respectively (Fig. 3). VCD is one of the few drugs effective at 40 min delay at the soman-induced SE model.

Figure 2.

Anticonvulsant dose-response curve of VCD (racemate) administered at 5, 20 and 40 min after onset of soman-induced (electrographic) status epilepticus (SE) in rats.

Figure 3.

Latency (mean and SEM) for seizure control – the time from when racemic-VCD was administered to rats 5, 20 and 40 min after seizure onset until the last epileptiform event could be detected on the EEG record.

Pharmacokinetics of VCD stereoisomers in rats

The pharmacokinetics of VCD stereoisomers was studied following ip administration (70 mg/kg) to rats. The dose was chosen for the PK study as the intermediate dose among the various ED50 values of VCD stereoisomers. The plasma concentration–time plots of VCD

individual stereoisomers are presented in Figure 4. The PK parameters of VCD four individual stereoisomers, calculated by non-compartmental analysis, are summarized in Supporting Information-Table 1. VCD had a stereoselective PK with (2S,3S)-VCD exhibiting the lowest clearance and consequently, a twice-higher plasma exposure (AUC) than all other stereoisomers. The apparent volume of distribution and half -life of VCD's four individual stereoisomers were similar and ranged between 1–1.6 L/kg and 2.1–3 h, respectively (Supporting Information-Table 1).

Figure 4.

Plasma concentration-time plots of VCD four individual stereoisomers obtained following i.p. administration of 70 mg/kg (of each compound) to rats. (The data on (2R,3S)-VCD and (2S,3S)-VCD are taken form Kaufmann et. al, 2010).

Teratogenicity

The teratogenic potential of racemic-VCD and its four individual stereoisomers was assessed for their ability to induce gross morphological defects in the SWV/Fnn mice that are highly susceptible to VPA-induced exencephaly. VPA, at a dose of 2.7 mmol/kg was embryotoxic and teratogenic causing almost two-fold increase in the resorption rate compared to the control group (11.9% vs 6.3% respectively) and NTDs in 29.1% of live fetuses. At a lower dose of 1.8 mmol/kg VPA was still embryotoxic (13.6% of resorptions) but the number of fetuses with exencephaly (2) was not statistically significant. In contrast to VPA, racemic-VCD and its four individual stereoisomers did not cause statistically significant increase of NTDs at doses of 257 or 389 mg/kg (Table 2). These doses are 3–12 times higher than VCD anticonvulsant-ED50 values. (2S,3S)-VCD, (2R,3S)-VCD and racemic-VCD were embryotoxic and induced resorptions in 16%, 23% and 21% of conceptions respectively, when tested at the higher 2.7 mmol/kg dose (Table 2).

Table 2.

Teratogenic Effect in the SWV Mouse Model of VCD and its stereoisomers

| Compound | Dose mg/kg (mmol/kg) |

No. of litters |

No. of implants |

No. of Resorptions (%) |

No. of live Fetuses (%) |

No. of normal Fetuses (%) |

No. of fetuses with NTDs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 25% CEL | 14 | 207 | 13 (6.3) | 194 (93.7) | 194 (100) | 0 |

| Na-VPAx | 452 (2.7) | 13 | 160 | 19 (11.9)* | 141 (88.1) | 100 (70.9) | 41 (29.1)* |

| Na-VPAx | 301 (1.8) | 12 | 154 | 21 (13.6)* | 133 (86.4) | 131 (98.5) | 2 (1.5) |

| VCDx | 389 (2.7) | 9 | 119 | 25 (21.0)* | 94 (79.0) | 94 (100.0) | 0# |

| VCDx | 257 (1.8) | 10 | 132 | 5 (3.8)# | 127 (96.2) | 126 (99.2) | 1 (0.8) |

| (2S, 3S)-VCD | 389 (2.7) | 22 | 301 | 50 (16.6)* | 251 (83.4) | 248 (98.8) | 3 (1.2)# |

| (2S, 3S)-VCD | 257 (1.8) | 19 | 244 | 15 (6.1)# | 229 (93.9) | 229 (100.0) | 0 |

| (2R, 3S)-VCDx | 389 (2.7) | 10 | 124 | 29 (23.4)*# | 95 (76.6) | 95 (100.0) | 0# |

| (2R, 3S)-VCDx | 257 (1.8) | 9 | 113 | 8 (7.1) | 105 (92.9) | 104 (99.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| (2S, 3R)-VCD | 387 (2.7) | 10 | 148 | 12 (8.1) | 136 (91.9) | 136 (100) | 0# |

| (2S, 3R)-VCD | 258 (1.8) | 10 | 141 | 10 (7.1) | 131 (92.9) | 131 (100) | 0 |

| (2R, 3R)-VCD | 387 (2.7) | 10 | 137 | 12 (8.8) | 125 (91.2) | 124 (99.2) | 1 (0.8)# |

| (2R, 3R)-VCD | 258 (1.8) | 12 | 167 | 12 (7.2) | 155 (92.8) | 155(100) | 0 |

– Results from Ref.11.

- significantly different when compared to the control group

- significantly different when compared to group treated with equimolar dose of VPA

Discussion

VCD Stereoisomers activity in anticonvulsant animal models

In the search for novel AEDs the present study describes the broad-spectrum anticonvulsant activity of VCD four stereoisomers. All four VCD stereoisomers possess a similar broad-spectrum anticonvulsant profile.. The anticonvulsant activity of VCD stereoisomers was equivalent to that of SPD stereoisomers in mice (ip) and rat (po).24 VCD (racemate) and its individual strereoisomers were is 4–16 times more potent than VPA in a wide array of anticonvulsant animal models.28

At present little can be said about the molecular mechanism through which VCD stereoisomers exert their anticonvulsant activity. These results would support the conclusion that VCD exerts its effects through an ability to prevent seizure spread and elevate seizure threshold. This conclusion is based on the marked effect exerted by VCD stereoisomers in the rat-MES test (seizure spread) and its ability to elevate seizure threshold in the scMet seizure model. VPA is a major AED with multiple mechanisms of action (MOA) that contribute to its activity in bipolar disoder.25,26 As an amide derivative of VPA it is likely that VCD has multiple MOA.

Anticonvulsant effects of VCD in animal models of SE

SE is initially treated with a benzodiazepine such as diazepam or lorazepam that are effective when given early after SE onset. However, the benzodiazepines lose their efficacy when given after 20 minutes after SE onset, and animals that experience prolonged SE quickly develop pharmacoresistant SE if treatment is not initiated within a short period after seizure onset.27

Racemic-VCD and two VCD stereoisomers, (2S,3S)-VCD and (2R,3S)-VCD, were found to be a highly effective anti-seizure drugs in the lithium-pilocarpine induced SE model when given at seizure onset. But in contrast to SPD that an ED50 value of 84 mg/kg.9, racemic-VCD (80 mg/kg) and three of its individual stereoisomers lost their activity in behavioral SE when administered 30 min after pilocarpine-induced SE onset. At electrographic SE (ESE) racemic-VCD was found to be less potent than SPD. VCD (180 mg/kg) stopped ESE when given 30 min after seizure onset while SPD (180 mg/kg) stopped ESE at 60 min. At 30 min SPD stopped ESE at a lower dose of 130 mg/kg.10

In contrast to the pilocarpine-induced SE model, racemic-VCD exhibited a potent activity in the soman-induced SE model when administered at 20 min and 40 min after onset of electrographic seizures in rats (Figs 2 and 3). This unique activity in eliminating ESE is not shared by benzodiazepines or other AEDs. In this soman-induced SE model VCD activity (ED50=60 mg/kg and ED50=62mg/kg at 20 and 40 min, respectively) was equipotent to that of SPD (ED50=71 mg/kg and ED50=72 mg/kg at 20 and 40 min, respectively).9, 28 Unlike VCD that is active only at the soman-induced SE model SPD (racemate and its individual stereoisomers) are active in both the pilocarpine- and soman-induced-SE models.24 VCD and SPD are two of the few drugs effective at 40 min delay at the soman-induced SE model.

PK analysis of VCD Stereoisomers

VCD had a stereoselective PK with (2S,3S)-VCD exhibiting the lowest clearance and consequently, two-fold elevated plasma exposure (AUC) than all other stereoisomers. Nerveless, there was no stereoselectivity in VCD anticonvulsant activity and each stereoisomer had similar ED50 values as did the racemic-VCD.

VCD is primarily eliminated by metabolism and its blood-to-plasma ratio is 1 (unity).29,30 Rat liver blood flow (Q) is 60–70 ml/min/kg.31 Assuming that VCD metabolism is mainly hepatic, then the liver extraction ratio (E=CL/Q=CLm/Q) of the various VCD stereoisomers ranges between 5% [(2S,3S)-VCD] to 12% [(2S,3R)-VCD]. A similar E value (E=5%) was previously calculated for racemic-VCD.30 If these rat data can be extrapolated to humans it is suggestive that each VCD individual stereoisomer will not be susceptible to hepatic first-pass effect after oral dosing, which was the case when racemic-VCD was given orally to humans.1,4 The clearance (CL/F) of the VCD individual stereoisomers was 6–10 times lower than those of SPD stereoisomers (Fig.1). Thus, the addition of one carbon to the VCD molecule has a profound effect on the clearance of the two homologous compounds VCD and SPD.24

Similar to the current rat study, in humans following oral administration of racemic-VCD (400mg) (2S,3R)-VCD had a clearance (CL/F) value twice higher than all other VCD individual stereoisomers.1 Stereoselective PK analysis across species of racemic-VCD showed that following iv administration of racemic-VCD to dogs (20 mg/kg) and rats (74 mg/kg) or mice (300 mg/kg, ip) there was a non-significant difference in the CL values of VCD individual stereoisomers.32 VCD stereoisomers' clearance (CL) values following iv administration to rats were similar to those found in the current study, indicating that VCD is completely absorbed following ip administration to rats.

Lack of teratogenicity of VCD and its individual stereoisomers

Since most if not all commercially available AEDs are teratogenic, it is essential to develop new AEDs that are non-teratogenic.33 VCD (racemate) and its four individual stereoisomers did not induce statistically significant increases in neural tube defects at doses 3–12 times higher than their anticonvulsant-ED50 values (Tables 1 and 2). The lack of teratogenicity of racemic-VCD, (2S,3S)-VCD and (2R,3S)-VCD was previously reported.11 Hereon we demonstrate that all VCD stereoisomers failed to induce NTD in SWV mice at doses (2.7mmol/kg=389 mg/kg) that were higher than the non-teratogenic dose (1.8 mmol/kg) of SPD and its stereoisomers.24 In contrast to VPA its constitutional isomer (and VCD corresponding acid) VCA was non-teratogenic and had a similar profile as VCD.11 A similar non-teratogenic profile was observed with VCD’s constitutional isomer propylisopropylacetamide (PID) and its two individual enantiomers.34 Thus, VCD and its stereoisomers are superior to VPA not only by exhibiting a more potent anticonvulsant activity but also by their reproductive safety.

These data coupled with head-to-head comparison of the teratogenicity between VCD (racemate) and VPA conducted following multiple dosing in mice, rats and rabbits16 show that in contrast to VPA VCD has a low teratogenic potential. Thus unlike VPA which is a pregnancy category D, VCD may receive category B35. This is also acknowledged in a recent VCD phase IIa paper entitled: :"Valnoctamide as a valproate substitute with low teratogenic potential in mania:…‥14".

Strereoselective Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Pharmacodyanmics (PD)

Binding of a racemic drug (e.g VCD, SPD) to the molecular targets that lead to its CNS activity (e.g. ion channel, a receptor or an enzyme) may be stereospecific and consequently, individual stereoisomers that may display distinguished PK behavior that could lead to stereoselective PD.17–18, 36 Consequently, consideration of chirality should be implemented into PK and PD studies.

The FDA’s 1992 policy “Statement for Development of the New Stereoisomeric Drugs” triggered the development of single individual stereoisomers instead of racemates.37 This policy coupled with marketing incentives of further profitability as a “line extension” has encouraged companies to look for chiral switches of established chiral drugs that were first introduced to the market as racemic mixtures.17–18

In the current study some stereoselectivity was observed in the mice-MES test where (2R,3R)- VCD was more potent than (2R,3S)-VCD and (2S,3S)-VCD. In the rat-MES test (2R,3S)-VCD had a more potent ED50 value (34mg/kg) than its diastereoisomer (2S,3S)-VCD (64mg/kg).11 In the rat-scMet test (2R.3S)-VCD was the most potent stereoisomer.

Bialer et al demonstrated a correlation between the anticonvulsant-ED50 values in mice and rats of various AEDs and their dose and therapeutic average steady-state plasma concentrations in patients with epilepsy38. This analysis shows that VPA is the least potent AED in anticonvulsant tests and thus VCD stereoisomers that are 4–16 time is more potent than VPA in various animal models28 may be more potent in patients The comparative analysis among various AEDs may also be useful for estimating target concentration range in humans of new AED candidates38.

Conclusions

VCD had a stereoselective PK with (2S,3S)-VCD exhibiting the lowest clearance and consequently, a two-fold higher plasma exposure than all other stereoisomers. Nerveless, there was less stereoselectivity in VCD anticonvulsant activity and each stereoisomer had similar ED50 values in most models. VCD stereoisomers (258 or 389 mg/kg) did not cause NTD at doses that are 3–12 times higher than VCD anticonvulsant-ED50 values.

If VCD would exert its broad-spectrum anticonvulsant activity due to a single MOA it is likely that it would exhibit stereoselective PD. The fact that there was no significant difference between racemic-VCD and its individual stereoisomers in most of the anticonvulsant rodent models (except the rat-scMet test) may indicate that VCD anticonvulsant activity is due to multiple MOA. The choice for further drug development between racemic-VCD and one of its individual stereoisomers will be based on comparative toxicological analysis and additional anticonvulsant testing that will discriminate between these five CNS-active compounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an unrestricted research grant (#039-4489 and #039-4576) from Israel Ministry of Defense, Medical Branch, Nuclear Biological Chemical (NBC) Protection Division and by an Inter-Agency Agreement between NIH/NINDS (Y1-O6-9613-01) and USAMRICD (A120-B.P2009-2).

The authors wish to thank Drs. John H. Kehne and Tracy Chen of the NIH–NINDS-Anticonvulsant Screening Program (ASP) for testing the compounds in the ASP. The authors also wish to acknowledge the technical assistance of the faculty and staff at the University of Utah Anticonvulsant Drug Development (ADD) Program who conducted the in vivo anticonvulsant testing, pilocarpine SE, and in vitro slice studies described in this manuscript. The anticonvulsant studies were supported by NINDS, NIH Contract No. NO1-NS-4-2359.

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army, Department of Defense or the U.S. Government

Dr. Meir Bialer has received in the last three years speakers or consultancy fees from Bial, CTS Chemicals, Desitin, Janssen-Cilag, Johnson & Johnson, Medgenics, Rekah, Sepracor, Teva, UCB Pharma and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Bialer has been involved in the design and development of new antiepileptics and CNS drugs as well as new formulations of existing drugs.

We, the authors, confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines

Abbreviations

- CNS

central nervous system

- AED

antiepileptic drug

- MES

maximal electroshock seizure

- scMet

subcutaneous metrazol

- SE

status epilepticus

- PI

protective index

- VPA

valproic acid

- LDA

lithium diisopropylamide

- DCM

dichloromethane

- THF

tetrahydoflurane

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- GC-MS

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

Footnotes

This work is abstracted from the PhD thesis of Mr. Tawfeeq Shekh-Ahmad in a partial fulfillment for the requirements of a PhD degree at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the US Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996) and the Animal Welfare Act of 1966 (P.L. 89-544), as amended.

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

None of the other authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Barel S, Yagen B, Schurig V, et al. Stereoselective pharmacokinetic analysis of valnoctamide in healthy subjects and in patients with epilepsy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;61:442–449. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bialer M, Yagen B. Valproic acid - Second generation. Neurotherapeutics. 4:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bialer M. Chemical properties of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;64:887–895. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.11.006. (2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bialer M, Haj-Yehia A, Barzaghi N, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a valpromide isomer, valnoctamide, in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;38:289–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00315032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bialer M. Clinical pharmacology of valpromide. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1991;20:114–122. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199120020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bialer M, White HS. Key factors in the discovery and development of new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:68–83. doi: 10.1038/nrd2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melissant CF, Vinks AATM, Sleeboom HP. Coma due to overdose of valnoctamide. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd [Dutch Med J] 1992;132:793–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stepansky W. A clinical study in the use of valmethamide, an anxiety-reducing drug. Curr Ther Res. 1960;2:144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White HS, Alex AB, Pollock A, et al. A new derivative of valproic acid amide possesses a broad-spectrum antiseizure profile and unique activity against status epilepticus and organophosphate neuronal damage. Epilepsia. 2012;53:134–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pouliot W, Bialer M, Hen N, et al. Electrographic analysis of the effect of sec-butyl-propylacetamide on pharmacoresistant status epilepticus. Neuroscience. 2013;231:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufmann D, Yagen B, Minert A, et al. Evaluation of the antiallodynic, teratogenic and pharmacokinetic profile of stereoisomers of valnoctamide, an amide derivative of a chiral isomer of valproic acid. Neuropharmacology. 2010;52:1228–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finnell RH, Bennett GD, Karras SB, et al. Common hierarchies of susceptibility to the induction of neural tube defects in mouse embryos by valproic acid and its 4-propyl-4-pentenoic acid metabolite. Teratology. 1988;38:313–320. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420380403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shalitiel G, Mark S, Kofman O, et al. Effect of valproate derivatives on human brain-myo-inositol-1-phosphate (MIP) synthase activity and amphetamine-induced rearing. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:402–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bersudsky Y, Applebaum J, Gaiduk Y, et al. Valnoctamide as valproate substitute with low teratogenic potential in mania: Double blind controlled clinical trial. Bipolar Disorder. 2010;12:376–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bialer M, Johannessen SI, Levy RH, et al. Progress report on new antiepileptic drugs: a summary of the Tenth Eilat Conference (EILAT X) Epilepsy Res. 2010;92:89–124. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bialer M, Johannessen SI, Levy RH, et al. Progress report on new antiepileptic drugs: A summary of the Eleventh Eilat Conference (EILAT XI) Epilepsy Res. 2013;103:2–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agranat I, Caner H, Caldwell J. Putting chirality to work: the strategy of chiral switches. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:753–68. doi: 10.1038/nrd915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucker GT. Chiral switches. Lancet. 2003;55:1085–1087. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bliss C. Vitamin Methods. New York: Academic Press; 1952. The statistics of bioassay with special reference to the vitamins; pp. 445–628. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonough JH, Shih TM. Pharmacological modulation of soman-induced seizures. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1991;17:203–215. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih TM, McDonough JH. Neurochemical mechanisms in soman-induced seizures. J Appl Toxicol. 1991;17:255–264. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1263(199707)17:4<255::aid-jat441>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finnell RH, Bielec B, Nau H. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 124 (Drug Toxicity in Embryonic Development II. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1997. Anticonvulsant drugs: Mechanisms and pathogenesis of teratogenicity; pp. 121–159. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finney DJ. Statistical logic in the monitoring of reactions to therapeutic drugs. Methods Inf Med. 1971;10:237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hen N, Shekh-Ahmad T, Yagen B, et al. Stereoselective pharmacoydnamic and pharmacokinetic analysis of sec-propyl-butylacetamide (SPD), a new CNS-active derivative of valproic acid with unique activity against status epilepticus. J Med Chem. 2013;56:6467–6477. doi: 10.1021/jm4007565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nalivaeva NN, Belyaev NCD, Turner AJ. Sodium valproate: an old drugs with new roles. THIPS. 2009;30:509–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bialer M. Why are antiepileptic drugs used for nonepileptic conditions? Epilepsia. 2012;50(Suppl 7):26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones DM, Esmaeil N, Maren S, et al. Characterization of pharmacoresistance to benzodiazepines in the rat Li-pilocarpine model of status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2002;50:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(02)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shekh-Ahmad T, Hen N, Yagen B, et al. Valnoctamide and sec-propyl-butylacetamide (SPD) for acute seizures and status epielpticus. Epilepsia. 2013;(Suppl. 5):98–101. doi: 10.1111/epi.12290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haj-Yehia A, Bialer M. Pharmacokinetics of a valpromide isomer, valnoctamide, in dogs. J Pharm Sci. 1988;77:831–834. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600771003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blotnik S, Bergman F, Bialer M. The disposition of valpromide, valproic acid and valnoctamide in brain, liver, plasma and urine of rats. Drug Metab Disposit. 1996;24:560–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altman PL, Dittmer DS. Biology data book 2nded., vol. 3 Bethesda: Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. Bethesda MD: 1974. pp. 1702–1710. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spiegelman O, Yagen B, Bennett GD, et al. Strereoselective pharmacokinetics of valnoctamide, a CNS-active chiral amide analogue of valproic acid in dogs, rats and mice. Ther Drug Monit. 2000;22:574–581. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200010000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meador KJ. Effect of in-utero antiepileptic drug exposure. Epilepsy Curr. 2009;8:144–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2008.00273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spiegelman O, Yagen B, Levy RH, et al. Strereoselective pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of propylisopropyl acetamide - a CNS-active chiral amide derivative of valproic acid. Pharm Res. 1999;16:1582–1588. doi: 10.1023/a:1018960722284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.FDA-Federal Register. Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products: Requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling. 2008;73:30381–30837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy RH, Boddy AV. Stereoselectivity in pharmacokinetics: A general theory. Pharm Res. 1991;8:551–555. doi: 10.1023/a:1015884102663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hubbard WK. FDA policy on period of marketing exclusivity for newly approved drug products with enantiomer active ingredients; request for comments. Federal Register. 1997;62:2167–2169. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bialer M, Twyman RE, White HS. Correlation analysis between anticonvulsant ED50 values of antiepileptic drugs in mice and rats and their therapeutic doses and plasma levels. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5:866–872. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.