Abstract

The regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels by protein kinase A (PKA) represents a crucial element within cardiac, skeletal muscle and neurological systems. Although much work has been done to understand this regulation in cardiac CaV1.2 Ca2+ channels, relatively little is known about the closely related CaV1.4 L-type Ca2+ channels, which feature prominently in the visual system. Here we find that CaV1.4 channels are indeed modulated by PKA phosphorylation within the inhibitor of Ca2+-dependent inactivation (ICDI) motif. Phosphorylation of this region promotes the occupancy of calmodulin on the channel, thus increasing channel open probability (PO) and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. Although this interaction seems specific to CaV1.4 channels, introduction of ICDI1.4 to CaV1.3 or CaV1.2 channels endows these channels with a form of PKA modulation, previously unobserved in heterologous systems. Thus, this mechanism may not only play an important role in the visual system but may be generalizable across the L-type channel family.

Phosphorylation of L-type calcium CaV channels by protein kinase A is essential for several physiological events. Here, the authors show how this kinase regulates CaV1.4 activity, suggesting a general regulatory mechanism for all L-type calcium channels.

Phosphorylation of L-type calcium CaV channels by protein kinase A is essential for several physiological events. Here, the authors show how this kinase regulates CaV1.4 activity, suggesting a general regulatory mechanism for all L-type calcium channels.

Phosphorylation, as one of the most ubiquitous forms of posttranslational modification, plays essential roles in biological functions1. Phosphorylation of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels by protein kinase A (PKA) is essential for normal cardiac function2, muscle contraction3 and neurological activity4. PKA-mediated phosphorylation underlies changes in the open probability of skeletal muscle CaV1.1 and cardiac CaV1.2 L-type calcium channels during the fight-or-flight response4,5, whereas phosphorylation of CaV1.3 channels has been implicated in shaping neuronal action potentials6. However, far less is known about the effects of phosphorylation on the CaV1.4 L-type channel, the main L-type channel in the retina7,8. PKA activity in the retina is robustly regulated by dopamine9 and dopamine fluctuates according to the circadian rhythm10. Thus, PKA regulation of CaV1.4 could modulate visual sensitivity during the day–night cycle, making phosphorylation of CaV1.4 channels a potentially important regulatory process required for normal visual function.

Similar to other L-type channels, CaV1.4 channels employ a form of feedback regulation called calmodulation11, to precisely tune Ca2+ entry through these channels. Calmodulin (CaM) is known to associate with the IQ domain of the channel carboxy terminus while in the Ca2+-free (apo) state12,13. The presence of apoCaM on the channel IQ significantly increases channel open probability (PO) as compared with the channel in the absence of apoCaM14. In addition, the presence of apoCaM enables Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI), whereby Ca2+ binding to the resident CaM results in a decrease in channel PO12. Several L-type channel splice variants exploit this calmodulation effect in order to tune the biophysical properties of channels expressed in different cell types15,16,17. In particular, long splice variants of CaV1.4 channels contain a CDI-inhibiting module (inhibitor of CDI, ICDI) within their distal C terminus18 (DCT), which competes with apoCaM for binding at the IQ domain19,20. By dislodging CaM, ICDI profoundly suppresses the channel PO and eliminates CDI. We hypothesize that a phosphorylation site in ICDI might be able to modulate this interaction, thus tuning channel PO and CDI. Moreover, ICDI is not limited to CaV1.4. Other L-type calcium channels, including CaV1.2 and CaV1.3, have similar motifs within their DCTs, providing a broader impact for such a mechanism.

Here we set out to determine whether CaV1.4 channels might indeed be modulated by PKA and what the underlying mechanism leading to such modulation might be. Remarkably, CaV1.4 channels exhibit robust PKA modulation of both the current amplitude and CDI. This co-regulation of channel opening and CDI stems from a mechanism whereby the ICDI of CaV1.4 channels competes with CaM binding to the channel IQ domain. Although this mechanism appears to be specific to CaV1.4 channels, this form of PKA modulation can be endowed onto other L-type channels by delivering ICDI1.4, demonstrating a modular and partially conserved mechanism for PKA regulation across L-type channels. Moreover, we identify S1883 within ICDI1.4 as the phosphorylation site for this form of PKA regulation. In all, PKA modulation of CaV1.4 Ca2+ channels, might be an important regulatory mechanism, enabling precise tuning of Ca2+ influx under various physiological conditions.

Results

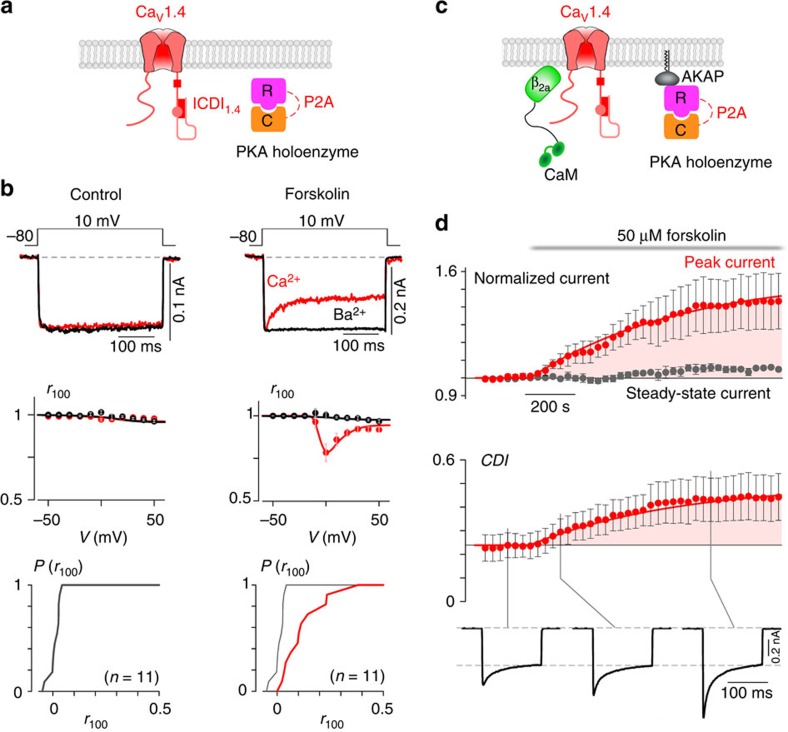

PKA activation regulates full-length CaV1.4 channels

Although CaV1.4 channels are known to exist in retinal cells7,8 and several other neuronal cell types21, they are rarely studied in their native environment. This is due in part to the difficulty in isolating and patch clamping these unique primary cells, as well as the low native open probability of the CaV1.4 channels14. These two features make whole-cell recordings of these channels in primary cells exceedingly challenging, limiting experiments to heterologous expression systems such as HEK293 cells. Although CaV1.4 channels do express in these model cells, reconstitution of PKA regulation in these cells has been challenging for other L-type calcium channels22,23,24. Even the strong PKA enhancement of cardiac CaV1.2 L-type Ca2+ channels, which is readily apparent in isolated myocytes, cannot be fully reconstituted in heterologous systems22,23,24,25. We therefore adjusted our recording conditions to maximize the potential for PKA modulation within HEK293 cells (see Methods). Specifically, we co-expressed full-length, wild-type CaV1.4 along with additional PKA holoenzyme (Fig. 1a). In addition, to minimize the perturbation of the cells, they were incubated with 50 μM forskolin at 30 °C for 60 min before whole-cell patch clamp recording. Indeed, these channels exhibited no CDI at baseline; however, following the forskolin incubation significant CDI was elicited, as demonstrated by the stronger decay in the Ca2+ (red) current as compared with the Ba2+ (black) current (Fig. 1b, top). Population data plotting the ratio of current remaining after 100 ms (r100) demonstrated a hallmark U-shaped dependence on voltage, further corroborating induction of CDI in CaV1.4 channels in response to PKA activity (Fig. 1b, middle). Although the extent of CDI varied somewhat from cell to cell, a significant right shift in the cumulative distribution of r100 demonstrates a clear effect of forskolin on CDI (Fig. 1b, bottom, red).

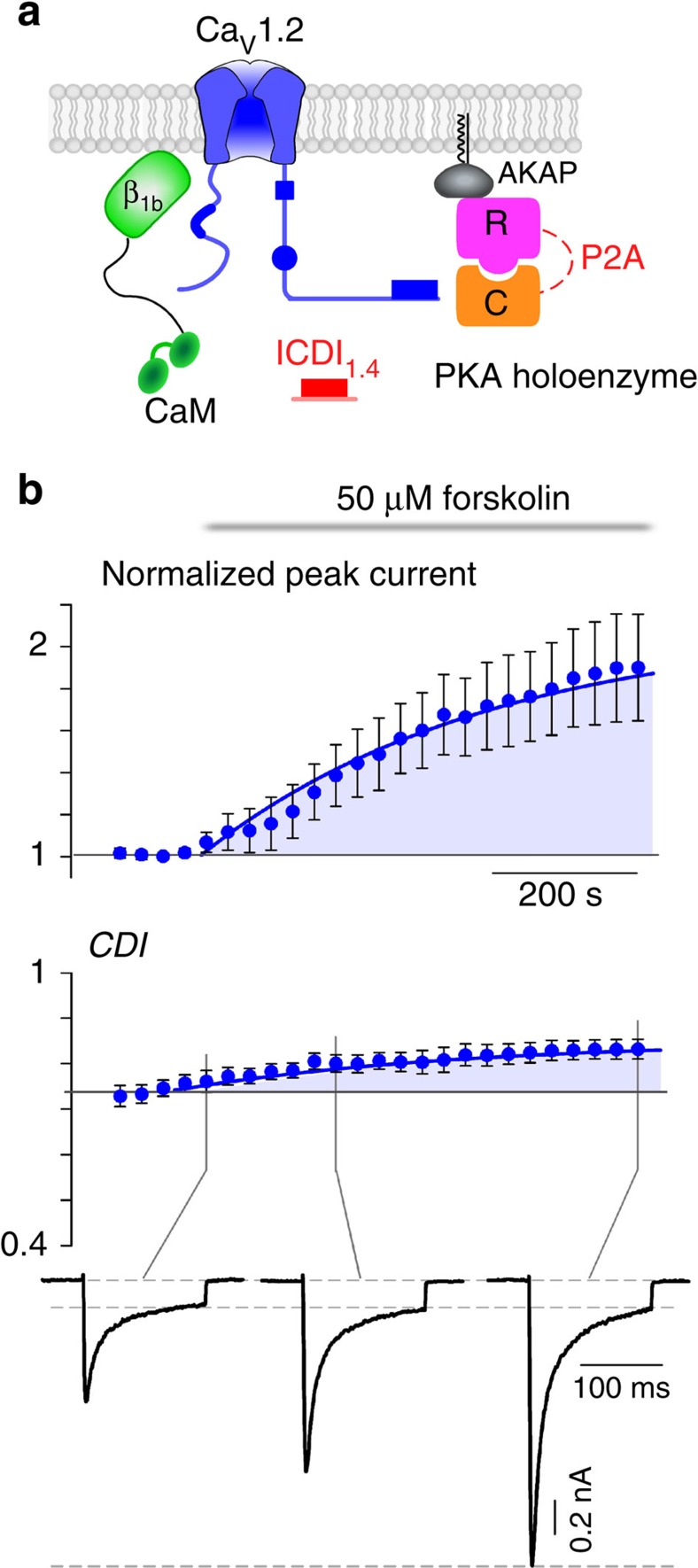

Figure 1. PKA regulation of full-length CaV1.4 channels.

(a) Schematic of HEK293 cells co-expressing CaV1.4 channels and PKA holoenzyme (catalytic subunit, C and regulatory subunit, R, linked by a P2A sequence at the DNA level, see Methods). (b) Left: minimal CDI at basal PKA levels. (Top) Exemplar of whole-cell current illustrates a lack of CDI, as seen by the minimal difference in decay of Ca2+ (red) versus Ba2+ (black) current. Vertical scale bar pertains to Ca2+ current; Ba2+ current scaled downwards ∼3 × to facilitate comparison of decay kinetics, here and throughout. Middle: population data confirms minimal CDI. The fraction of peak current remaining after 100-ms (r100) is plotted versus step voltage (V), for mean Ba2+ (black) and Ca2+ (red) currents±s.e.m. Bottom: the tight cumulative distribution of r100 across all cells also indicates minimal CDI. Right: CDI emerges after incubation in 50 μM forskolin at 30 °C for 60 min. Format as left. Bottom right: red trace indicates a right shift and increased spread in the cumulative distribution as compared with without forskolin (grey). (c) Schematic of co-expression of CaV1.4 channels with PKA holoenzyme, AKAP79 and β2a tethered CaM, which allowed longer whole-cell patching without loss of PKA or CaM. (d) Time course of normalized peak current (red) and steady-state current (grey) in response to the addition of 50 μM forskolin, evoked every 30 s by depolarizations to 20 mV (top). The corresponding increase in CDI (middle) from whole-cell Ca2+ currents. Currents were normalized to baseline. CDI was measured as 1−r100. All error bars indicate ±s.e.m. (n=4 cells). Corresponding current waveforms are displayed below.

Although the effect on CDI is compelling, stronger evidence would require dynamic modulation of PKA activity within a cell. Cognizant of the challenges introduced by dialysis of the cytosol during whole-cell patch clamping, we adjusted conditions to reduce this confounding factor. CaM was tethered to the β2a subunit of the channel and AKAP79 was co-expressed to anchor PKA to the membrane and reconstitute the native PKA system described in primary cells4,5,26 (Fig. 1c). Moreover, experiments were carried out at a temperature of 30 °C, to enhance enzyme activity as compared with room temperature (see Methods). With the system thus optimized, we were indeed able to demonstrate a large dynamic PKA response. A 20 mV depolarizing step was applied for 150 ms every 30 s, allowing resolution of the current amplitude and CDI over the time course of forskolin wash-on (Fig. 1d). The addition of forskolin caused a steady increase in peak current amplitude (red), reaching a level significantly larger than the pre-forskolin current. The steady-state current, as measured after 100 ms of depolarization, did not change significantly (grey). As a result, a corresponding increase in CDI was also seen (bottom). Thus, wild-type CaV1.4 channels exhibit robust PKA modulation of both channel opening and CDI.

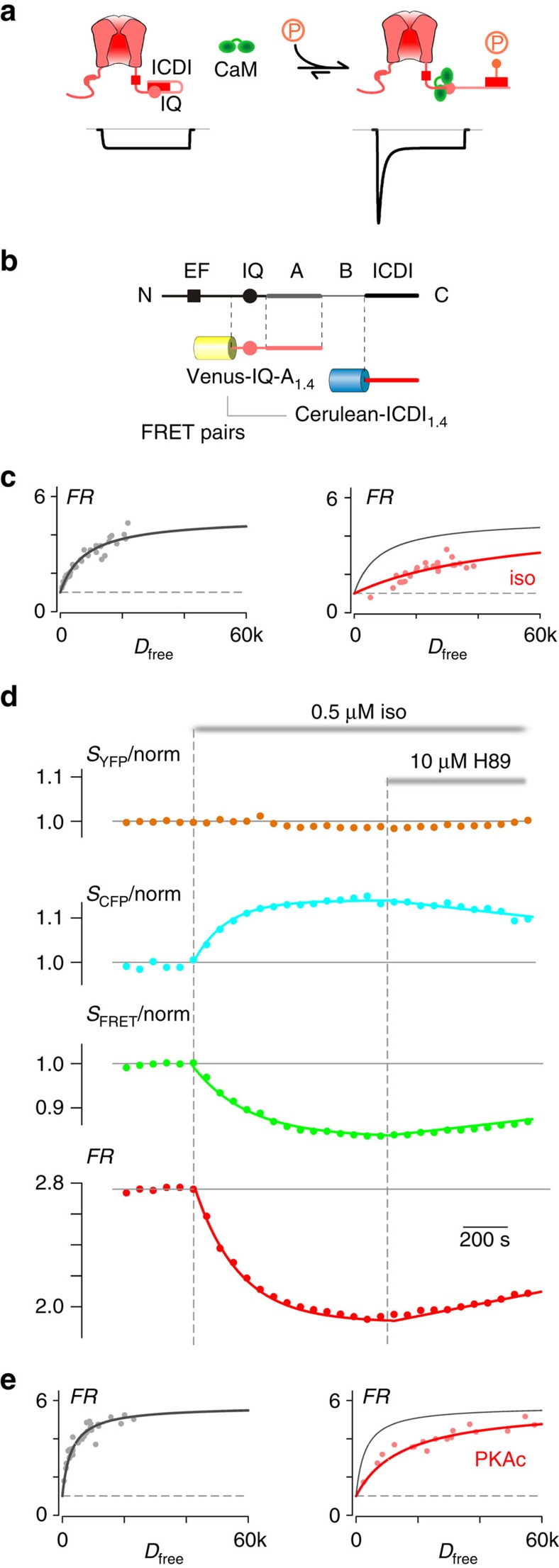

PKA regulation of the IQ and ICDI interaction in CaV1.4

The effects of PKA activity on channel PO and CDI is reminiscent of a previous study whereby CaM was enriched near the CaV1.3S/1.4DCT chimeric L-type channel via rapamycin-induced dimerization14. Thus, a possible underlying mechanism of PKA modulation of CaV1.4 channels may involve a similar CaM centric mechanism. In particular, the IQ region of calcium channels is known to bind to apoCaM, enhancing channel PO and enabling CDI upon Ca2+ entry. In addition, the ICDI domain in certain L-type Ca2+ channels is known to bind to the IQ region of the channel, displacing CaM and reducing the CDI and PO of the channel14,20. We hypothesized that the PKA modulation of CaV1.4 channels might use this regulatory mechanism, such that ICDI bound to the IQ region at baseline might be displaced by CaM following PKA activation (Fig. 2a). With CaM replacing ICDI on the IQ region of the channel, the channel PO would be increased and CDI enabled14. We thus sought to assess whether the interaction between the ICDI and IQ domains might be modulated by PKA phosphorylation. To this end, we used a live-cell fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) two-hybrid assay, pairing Venus-tagged IQ domains against Cerulean-tagged ICDI domains from CaV1.4 channels. Although not required for CaM binding27, the downstream A-region18,20 was included within our IQ construct (IQ-A), as it contributes to the binding between the IQ and ICDI domains28. Cognizant that full-bore PKA signalling is best conserved within certain native rather than model cells2,22,23,25,29, we performed FRET assays in adult guinea pig ventricular myocytes (aGPVMs), which are renowned for their strong PKA signalling2. The FRET pairs were transduced into aGPVMs via adenoviral vectors, allowing rapid and tunable expression within acute (1 day) myocytes30.

Figure 2. PKA regulation of the interaction between IQ and ICDI domains in CaV1.4.

(a) PKA regulation of L-type Ca2+ channel calmodulation. Left: ICDI module (red rectangle) on the DCT of the channel interacts with the IQ domain (pink circle) and dislodges CaM (green dumbbell). Without CaM, channels have low PO and minimal CDI (idealized current underneath the cartoon). Right: PKA phosphorylation (orange lollipop) could weaken the IQ/ICDI interaction and allow CaM to rebind, thus increasing channel PO and CDI. (b) Diagram of the C-tail of the channel illustrating the relevant FRET pairs, Venus-tagged IQ-A domains and Cerulean-tagged ICDI domain from CaV1.4. (c) FRET binding curve for Venus-IQ-A1.4 paired with Cerulean-ICDI1.4 in aGPVMs (grey). Isoproterenol (0.5 μM iso; red) decreases the relative binding affinity. Each point indicates a single cell. The control binding curve is replicated as the grey curve in the right-hand panel here and throughout. FR, FRET ratio; Dfree, relative concentration of unbound Cerulean-tagged ICDI1.4. (d) Kinetics of normalized fluorescent signals from YFP channel (SYFP), CFP channel (SCFP), FRET channel (SFRET) and calculated FR from an exemplar aGPVM expressing Venus-IQ-A1.4 and Cerulean-ICDI1.4, with 0.5 μM isoproterenol and 10 μM H89 added as indicated. Fluorescent signals were normalized to baseline. (e) FRET binding curve for Venus-IQ-A1.4 paired with Cerulean-ICDI1.4 in HEK293 cells (grey). Overexpression of PKAc (red) reduces the binding.

Indeed, FRET two-hybrid measurements in aGPVMs yielded a robust binding curve (Fig. 2c, black and Supplementary Table 1), indicating a clear interaction between these two channel domains. Remarkably, however, this interaction is largely disrupted when PKA is activated by the addition of 0.5 μM isoproterenol (Fig. 2c, red). Moreover, this PKA effect can be elicited as a dynamic response within an exemplar myocyte (Fig. 2d). The application of 0.5 μM isoproterenol decreases the FRET ratio (FR) exponentially (red), indicating a disruption in binding. Of note, the individual CFP and FRET signals have corresponding changes, whereas the YFP signal remains relatively stable when independently excited, indicating a genuine FRET response rather than an artefact due to isoproterenol acting directly on the fluorophores. Importantly, the decrease in FR can be reversed by inhibiting PKA via addition of the PKA inhibitor H89 (Fig. 2d), demonstrating a PKA-specific effect.

The discovery that the binding between IQ and ICDI domains in CaV1.4 can be attenuated by PKA activation in aGPVMs is compelling; however, the functional implications of this modulation could best be probed in a heterologous expression system where full control of channel and interacting partners is possible13. We therefore sought to reconstruct the PKA regulation of IQ binding with ICDI in HEK293 cells. We first attempted to replicate the PKA modulation of this interaction through the application of forskolin; however, the effect of forskolin was minimal (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Reasoning that HEK293 cells may have decreased endogenous PKA signalling as compared with aGPVMs, we overexpressed the constitutively active catalytic subunit of PKA (PKAc) and found that the binding of CaV1.4 IQ-A with ICDI was indeed reduced in HEK293 cells (Fig. 2e), thus rationalizing the overexpression of PKA holoenzyme in our whole-cell experiments (Fig. 1). Overall, the binding of IQ-A and ICDI can be dynamically modulated by PKA phosphorylation in a reversible manner, supporting the hypothesis that modulation of this interaction underlies the PKA regulation of CaV1.4 channels.

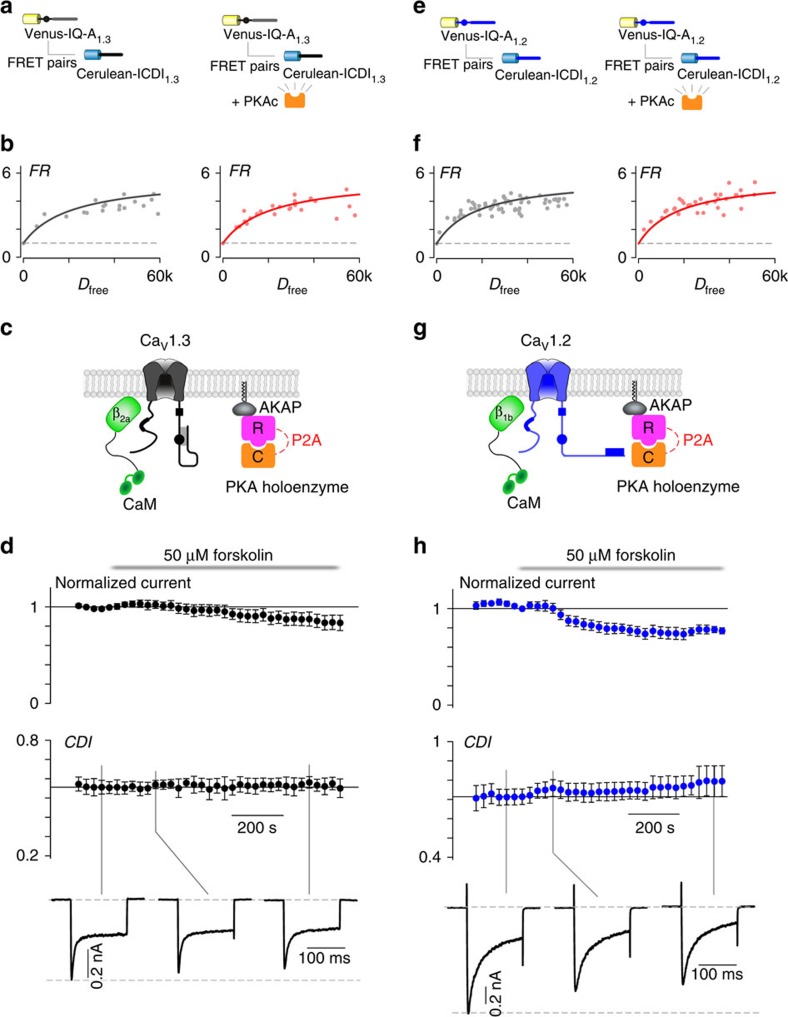

Lack of ICDI-mediated PKA regulation of CaV1.3 and CaV1.2

The ICDI domain of CaV1.4 exhibits significant sequence homology to the ICDI domain of other L-type Ca2+ channels. In fact, the ability of ICDI to compete with CaM for binding to the IQ domain of the channel has been demonstrated for both CaV1.3 and CaV1.2 channels14,20,28. We therefore wondered whether these channels may also employ a similar mechanism of PKA phosphorylation. To test this, we used the FRET two-hybrid binding assay to probe for interactions between the IQ and ICDI regions of CaV1.3 and 1.2 channels (Supplementary Table 1). As expected from previous studies, the ICDI1.3 bound well to IQ-A1.3; however, PKA phosphorylation failed to modulate this interaction in either HEK293 cells (Fig. 3b) or aGPVMs (Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, even with the enhanced PKA expression system used for CaV1.4 channels (Fig. 1), forskolin failed to induce a change in CDI or current amplitude of CaV1.3 channels in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3c,d). Nearly identical results were seen for CaV1.2 channels, where significant binding between the ICDI and IQ domains is unperturbed by PKA activation (Fig. 3e,f and Supplementary Fig. 2) and no modulation of CDI or current amplitude can be seen in the heterologous expression system (Fig. 3g,h). Thus, despite the sequence similarity of IQ and ICDI domains across CaV1.2, 1.3 and 1.4, the PKA regulatory mechanism is unique to CaV1.4.

Figure 3. PKA does not regulate the interaction of IQ and ICDI domains in CaV1.3 or CaV1.2 channels.

(a,b) Overexpression of PKAc does not change the binding between IQ-A1.3 and ICDI1.3 in HEK293 cells. (c) Schematic of co-expression of CaV1.3 with PKA holoenzyme, AKAP79 and β2a tethered CaM, which allowed longer whole-cell patching without loss of PKA or CaM. (d) Time course of normalized peak current (top) and CDI (middle) in response to the addition of 50 μM forskolin (n=5 cells). Corresponding current waveforms are displayed below. (e, f) Overexpression of PKAc does not change binding between IQ-A1.2 and ICDI1.2 in HEK293 cells. (g) Schematic of co-expression of CaV1.2 with PKA holoenzyme, AKAP79 and β1b tethered CaM, which allowed longer whole-cell patching without loss of PKA or CaM. (h) Time course of normalized peak current (top) and CDI (middle) in response to the addition of 50 μM forskolin (n=4 cells). Corresponding current waveforms are displayed below.

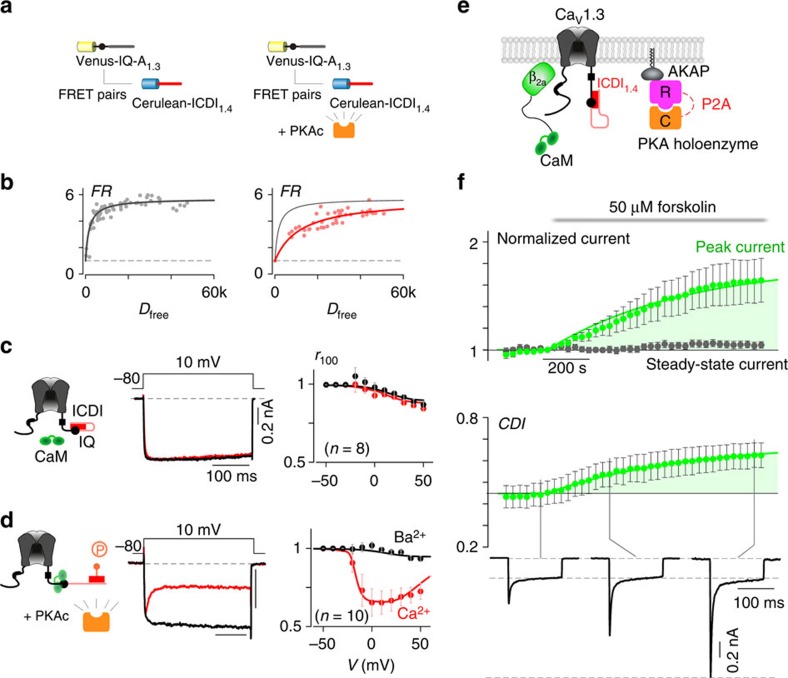

Engineering ICDI-mediated PKA regulation in CaV1.3 channels

To test our hypothesis that PKA regulation of CaV1.4 channels is the direct result of a phosphorylation-induced change in binding affinity between the channel IQ region and the ICDI domain, we sought to recreate this form of regulation in a channel which does not natively display such regulation. We thus sought to endow CaV1.3 channels with ICDI-mediated PKA regulation by manipulating the ICDI domain. We began by pairing the CaV1.3 channel with the ICDI domain from CaV1.4 (ICDI1.4) as previous studies have demonstrated an alteration in both the CDI and channel PO as a result of this interaction20,28. To test whether the interaction between the CaV1.3 IQ domain (IQ-A1.3) and ICDI1.4 could be modulated by PKA, we again used FRET two-hybrid to characterize the interaction of the two channel segments. Indeed, FRET two-hybrid measurements in aGPVMs yielded a robust binding curve (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1), indicating a clear interaction between these two channel domains. This interaction, however, is largely disrupted when PKA is activated by the addition of 0.5 μM isoproterenol (red), an effect that can also be elicited as a dynamic response within an exemplar myocyte (Supplementary Fig. 3) and can be reversed either by washing off isoproterenol or by inhibiting PKA via addition of either the wide-spectrum kinase inhibitor staurosporine or the PKA inhibitor H89 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, this PKA effect can be recreated in HEK293 cells (Fig. 4b), indicating a robust effect. Thus, the binding of IQ-A1.3 and ICDI1.4 can be dynamically modulated by PKA phosphorylation.

Figure 4. PKA regulation of chimeric CaV1.3S/1.4DCT channels in HEK293 cells.

(a) FRET binding assays between Venus-IQ-A1.3 and Cerulean-ICDI1.4 demonstrating the effect of PKAc overexpression. (b) PKAc reduces the binding between IQ-A1.3 and ICDI1.4. (c) Cartoon (left) of the chimeric channel CaV1.3S/1.4DCT made by attaching the DCT of CaV1.4 (including ICDI, red) to a truncated CaV1.3. Exemplar whole-cell current (middle) and population data (right) illustrates a lack of CDI. (d) Overexpression of PKAc (left) restored CDI of this chimeric channel, showing a strong decay of Ca2+ current (red) compared with Ba2+ current (black). The classic U-shaped voltage dependence of CDI is seen in the population data (right). (e) Schematic of co-expression of CaV1.3S/1.4DCT with PKA holoenzyme, AKAP79 and β2a tethered CaM, which allowed longer whole-cell patching without loss of PKA or CaM. (f) Time course of normalized peak current (green) and steady-state current (grey) in response to the addition of 50 μM forskolin, evoked every 30 s by depolarizations to 20 mV (top). The corresponding increase in CDI (middle) from whole-cell Ca2+ currents. Currents were normalized to baseline. CDI was measured as 1−r100. All error bars indicate ±s.e.m. (n=6 cells). Corresponding current waveforms are displayed below.

Given the ability of ICDI1.4 to compete with CaM for the CaV1.3 channel IQ region20, we tested whether disruption of IQ/ICDI binding by PKA might affect channel CDI. We used the chimeric CaV1.3S/1.4DCT channel14,20 (CaV1.3 with the DCT replaced by that of CaV1.4) as introduction of ICDI1.4 in this channel is known to ablate the CDI of wild-type CaV1.3 (ref. 20), as seen by the minimal difference in the decay of Ca2+ (red) versus Ba2+ (black) current (Fig. 4c). However, if PKAc is now overexpressed in these cells, CDI is restored (Fig. 4d). Population data again demonstrates a hallmark U-shaped dependence on voltage, further corroborating a restoration of CDI in the chimeric channel due to PKA activity. To confirm that this effect can be induced by activating PKA, we co-expressed the chimeric CaV1.3S/1.4DCT channel with PKA holoenzyme and incubated the cells with 50 μM forskolin at 30 °C for 30 min before whole-cell patch clamp recording. Indeed, incubation with forskolin restored a significant amount of CDI as compared with that without forskolin (Supplementary Fig. 4). This restoration of CDI is indicative of a shift in the binding of the IQ region from ICDI1.4 back to CaM in the phosphorylated state (Fig. 2a).

Based on our hypothesis (Fig. 2a), phosphorylation of ICDI by PKA should increase the channel PO, in addition to restoring CDI. To observe the concurrent increase in PO and CDI, we added 50 μM forskolin, while recording whole-cell Ca2+ currents at a bath temperature of 30 °C. The addition of forskolin caused a steady increase in peak current amplitude (Fig. 4f, green), reaching a level several fold larger than the pre-forskolin current. At the same time, the steady-state current remaining after 100 ms was remarkably stable (grey), resulting in an increase in CDI. This outcome is consistent with a previous study, whereby CaM was enriched near the CaV1.3S/1.4DCT channel via rapamycin-induced dimerization14, further substantiating the hypothesis that PKA activation results in increased CaM binding to the channel IQ due to a reduction in the affinity of IQ1.3 with ICDI1.4.

ICDI1.4 as a modular phospho-switch for CaV1.2 channels

Beyond CaV1.3, ICDI1.4 was also able to bind to IQ-A1.2 in a PKA-sensitive manner (Supplementary Fig. 2). We wondered whether this ICDI1.4 module could serve as a synthetic phospho-switch for CaV1.2 Ca2+ channels, able to be plugged into a system by co-expression as a cytosolic peptide. Such synthetic modulation of the CaV1.2 channel may be of particular interest, as these channels are known to undergo a large increase in current amplitude in response to PKA activation in myocytes; however, this effect is difficult to replicate in recombinant systems22,23. We therefore sought to use ICDI1.4 to generate PKA modulation of CaV1.2 channels in HEK293 cells. To maintain the properties of cardiac CaV1.2 channels as much as possible in our recombinant system, we co-expressed ICDI1.4 as a peptide along with the full-length cardiac CaV1.2 channel and used the β1b Ca2+ channel subunit, which more closely recapitulates the inactivation profile found in native cardiac myocytes29 (Fig. 5a). As before, CaM was linked to the β-subunit and AKAP was co-expressed so as to reduce dialysis of the key elements. Under these conditions, application of 50 μM forskolin largely increased the peak amplitude (Fig. 5b), similar to the native PKA upregulation of cardiac CaV1.2 channels (Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, an increase in CDI was seen even in the presence of significant voltage-dependent inactivation due to the use of the β1b-subunit31. Thus, the effect of ICDI1.4 on channel regulation demonstrated in the chimeric CaV1.3S/1.4DCT channel appears to be generalizable to other L-type Ca2+ channels. Moreover, ICDI1.4 need not be covalently attached to the channel, but rather is capable of acting as a diffusible CDI/PO switch, which can be turned off by PKA phosphorylation.

Figure 5. Synthetic PKA regulation of CaV1.2 in HEK293 cells.

(a) Schematic of full-length CaV1.2 channel, PKA holoenzyme (R and C) and ICDI1.4 peptide, along with β1b tethered CaM and AKAP79. (b) Time course of normalized peak current (top) and CDI (middle), from whole-cell Ca2+ currents, evoked every 30 s by depolarizations to 20 mV. Currents were normalized to baseline. CDI was measured as 1−r100. All error bars indicate ±s.e.m. (n=6 cells). Corresponding current waveforms are displayed below.

Identification of the PKA phosphorylation site within CaV1.4

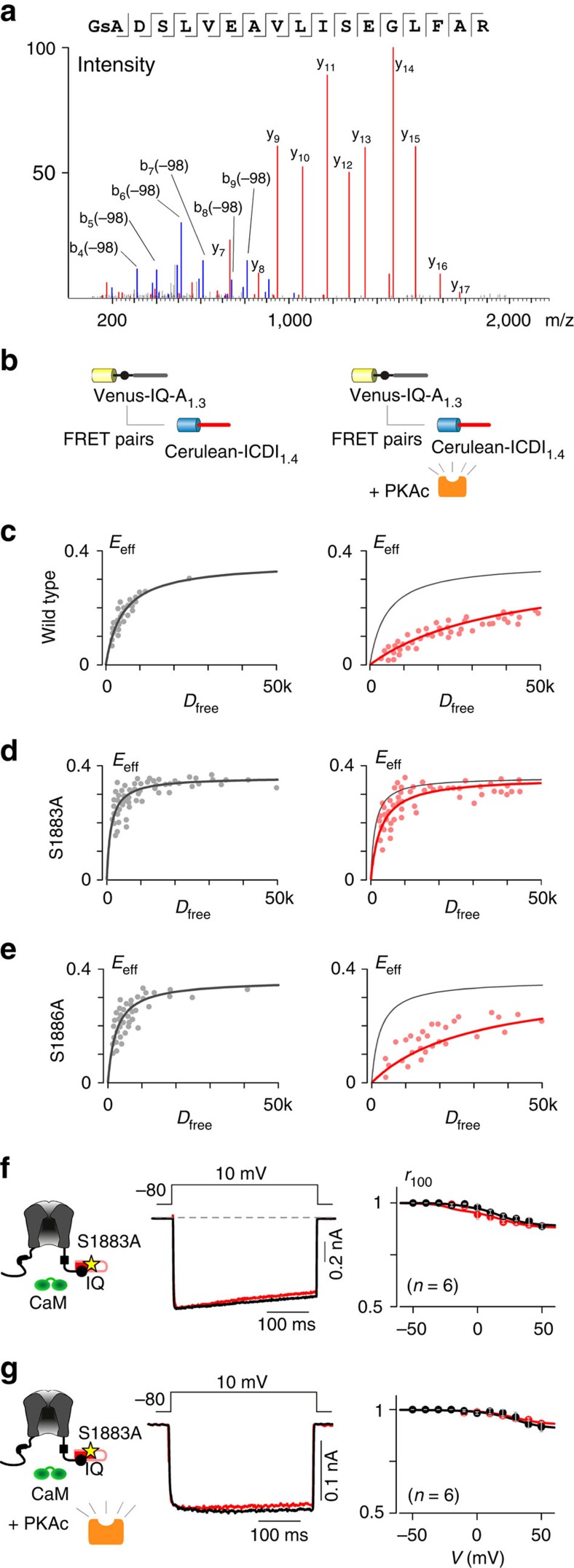

Thus far, we have demonstrated that elevated PKA activity correlates with increased peak current amplitude and CDI of L-type Ca2+ channels in the presence of ICDI1.4. We hypothesized that this effect is due to direct phosphorylation of ICDI1.4; however, an indirect effect due to phosphorylation of an unknown ICDI-interacting element could produce a similar result. As a first step towards identifying the site, we used the bioinformatics tool pkaPS32 to predict potential PKA phosphorylation sites within ICDI1.4. From this prediction algorithm, S1883 appeared to be the most probable site (Supplementary Fig. 6). As this motif is not easily recognized by currently available phospho-specific antibodies, we employed mass spectroscopy to identify phosphorylation sites within ICDI1.4. To induce phosphorylation, a histidine-tagged ICDI1.4 peptide was co-expressed with the PKA holoenzyme in HEK293 cells and subjected to 1 h of forskolin treatment. This peptide was purified using the histidine tag and analysed by mass spectroscopy, which revealed that S1883 is indeed phosphorylated (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 7); however, an additional phosphorylation site at S1886 could not be ruled out (see Methods).

Figure 6. Identification of the PKA phosphorylation site within ICDI1.4.

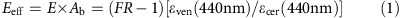

(a) The mass spectra of the ICDI1.4 peptide, showing phosphorylation at S1883. (b) Flow-cytometric FRET binding assays (c–e) between Venus-IQ-A1.3 and Cerulean-ICDI1.4 demonstrating the modulation of binding due to PKAc overexpression. (c) Overexpression of PKAc reduced binding between IQ-A1.3 and wild-type ICDI1.4. (d) Overexpression of PKAc did not affect binding between IQ-A1.3 and ICDI1.4 harboring an S1883A mutation. (e) Overexpression of PKAc reduced binding between IQ-A1.3 and ICDI1.4 harbouring an S1886A mutation. (f) Similar to wild-type CaV1.3S/1.4DCT channels (Fig. 4c), CaV1.3S/1.4DCT channels containing the S1883A mutation had minimal CDI. (g) Unlike wild-type CaV1.3S/1.4DCT (Fig. 4d), CaV1.3S/1.4DCT channels with the S1883A mutation did not exhibit increased CDI with overexpression of PKAc.

Having established S1883 as a potential PKA phosphorylation site, we sought to determine whether this site is responsible for the functional modulation of the channel. To confirm that the site is required for the PKA modulation of binding between L-type channel IQ regions and ICDI1.4, we used a flow-cytometer-based high-throughput platform for live-cell FRET two-hybrid binding, which was recently developed by our lab33. As seen by traditional FRET two-hybrid binding (Fig. 4b), overexpression of PKAc reduced the binding affinity of Venus-tagged IQ-A1.3 and Cerulean-tagged ICDI1.4 peptides (Fig. 6b,c and Supplementary Table 2). However, when S1883 within ICDI1.4 was mutated to alanine, the PKA modulation of the interaction was abolished (Fig. 6d). In contrast, if S1886 was mutated to alanine, PKA regulation was preserved (Fig. 6e). Finally, we probed the functional effect of the S1883A mutation via whole-cell patch clamp recording. The CaV1.3S/1.4DCT chimeric channel was used for these experiments, as it expresses well and exhibits robust and consistent PKA modulation. Mutation of S1883 to alanine had no effect on channel properties in the absence of PKA (Fig. 6f) and overexpression of PKAc failed to alter CDI (Fig. 6g), confirming that S1883 is a novel and functional PKA phosphorylation site within the CaV1.4 ICDI domain.

Discussion

PKA phosphorylation of ICDI1.4 has significant, previously unreported effects on wild-type CaV1.4 channels. Such PKA regulation may have important physiological consequences. CaV1.4 is the main L-type Ca2+ channel in the retina7,8. Unfortunately, the diminutive size of the photoreceptors and small PO of CaV1.4 channels makes direct measurements of PKA modulation within this native system exceedingly challenging. Nonetheless, the creation of a robust PKA system in HEK293 cells has enabled new mechanistic insight. We now know that PKA phosphorylation of ICDI1.4 disrupts IQ binding, allowing CaM to bind the IQ region, thus increasing channel PO and CDI. Such a mechanism may well be at play in the retina. Ca2+ currents within photoreceptors exhibit a modest amount of CDI, which had previously been attributed to a mixture of CaV1.4 channel splice variants17,34. Here we have demonstrated that even the long splice variant, containing ICDI1.4, is capable of supporting CDI under elevated PKA activation and probably contributes to the CDI seen in these cells. Moreover, ICDI1.4 is highly expressed in the retina (Supplementary Fig. 8a) where PKA activity is robustly regulated by dopamine9. As the dopamine fluctuations in the retina occur according to the circadian rhythm, they exhibit oscillations with periods lasting for many hours10 rationalizing the relatively slow kinetics of CaV1.4 regulation by PKA (Fig. 1d). Thus, PKA regulation of CaV1.4 could modulate visual sensitivity during the day–night cycle. In fact, channelopathic mutations in CaV1.4, which cause premature truncation before the ICDI domain display increased current amplitudes, augmented CDI and cause congenital stationary night blindness19,35. We therefore tested the congenital stationary night blindness channels CaV1.4K1591X in HEK cells and found that the channels do indeed exhibit significant CDI at baseline and have no response to 50 μM forskolin (Supplementary Fig. 8b,c) as predicted by the loss of the ICDI domain and S1883. Thus, PKA-mediated phosphorylation of the ICDI domain may play a critical role in low-light adaptation and normal visual function.

Beyond CaV1.4 channels, ICDI1.4 was able to endow chimeric CaV1.3 and 1.2 channels with robust PKA modulation, demonstrating a generalizable mechanism for regulation of L-type channel CDI and PO. Moreover, ICDI1.4 was also able to act as a synthetic phospho-switch when co-expressed as a separate peptide with CaV1.2 channels. This synthetic PKA modulation of channel opening and CDI could be a valuable tool to study the physiological role of CDI and PO, as this small peptide could be easily transduced into native cells. Moreover, co-expression of this peptide at basal PKA levels mimics the properties of certain long Ca2+ channel splice variants14, whereas elevation of PKA activity reverts the phenotype of these channels to that of a short splice variant. As such, this tool could aid in understanding the functional effects of alterations in splice variant expression in different cell types.

Such a synthetic phospho-switch may have added value beyond that of a novel tool for regulating L-type Ca2+ channels. It may shed light on the mechanism underlying native PKA regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels. In particular, the regulation of cardiac CaV1.2 channels by PKA is a critical feature of the fight-or-flight response, but the full mechanistic pathway underlying this regulation remains under debate23,24,25,36. Although PKA activation readily increases CaV1.2 current by several fold in adult cardiomyocytes, such large PKA upregulation is not often observed in heterologous systems such as HEK293 cells22,23, even in the presence of exogenous PKA holoenzymes (Fig. 3g,h). It appears then that there must be a critical element in myocytes, which is lacking in recombinant systems22,25. Given the ability of ICDI1.4 to modulate CaV1.2 channel PO in a phosphorylation-dependent manner, we wonder whether the missing element in myocytes may employ a similar strategy. Thus, searching for proteins capable of binding channel IQ domains may prove a useful approach.

To ensure the presence of all key elements of the PKA pathway within our binding assay, we implemented quantitative live-cell FRET two-hybrid binding in acutely isolated aGPVMs. This system enabled us to probe the PKA modulation of IQ/ICDI1.4 interactions, a phenomenon that was not initially observable in HEK293 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a). This failure of forskolin to modulate the IQ/ICDI1.4 interactions in HEK293 cells at baseline points to an important limitation of these cells. Although these cells have proven quite useful for studying many types of PKA modulation including HERG37, KV1.1 (ref. 38) and nicotinic receptors39, they appear less ideal for studying the modulation of L-type Ca2+ channels. It therefore seems likely to be that these phosphorylation targets have different thresholds for PKA modulation and model systems in which PKA is sufficient for one application may not be suitable for all target proteins.

In all, we have demonstrated that the repertoire of PKA regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels extends to CaV1.4 channels expressed in a heterologous system. The identification of the phosphorylation site within the CaV1.4 ICDI domain fits well with a mechanism in which PKA-mediated phosphorylation alters the binding affinity between the IQ and ICDI domains of CaV1.4, thus tuning the extent of CDI and channel PO via competitive displacement of CaM. Although conformation of this effect in a native system remains to be demonstrated, the distribution of CaV1.4 channels in the retina points to a potentially important role in the visual system and in tuning the circadian rhythm. Overall, this modulatory scheme may represent a general mechanism by which various L-type channels could be modulated by yet-to-be-identified competitors of CaM.

Methods

Molecular biology

The CaV1.3 channel (in pcDNA6) was derived from the rat brain variant (AF307009.1)40. CaV1.2 (in pGW) is identical to rabbit NM001136522 (ref. 41) and CaV1.4 (in pCDNA3) is the human clone corresponding to NM00718 (ref. 14). CaV1.3S/1.4DCT (in pcDNA6) was made by fusing with the DCT of CaV1.4 to the CaV1.3 channel backbone (truncated after the IQ domain)20. Briefly, the DCT was PCR amplified and ligated into CaV1.3 via a unique XbaI site. To generate the point mutation (S1883A) in the CaV1.3S/1.4DCT chimeric channel, the mutation was first introduced within the CaV1.4 distal C-tail peptide by QuickChange mutagenesis (Agilent) before PCR amplification and insertion into the CaV1.3 channel backbone, using the same strategy as the wild-type CaV1.3S/1.4DCT chimeric channel. β2a-Gly8-CaM (in pcDNA3) was made by deleting the stop codon of rat β2a and introducing a NotI site via PCR cloning. XbaI-glycine8-CaM-ApaI was then cloned into the XbaI site42. This construct was used for experiments in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 8; β2a-Gly32-CaM was made by extending the number of glycine residues in the linker from 8 to 32, using similar strategies43 and was used in experiments for Figs 3d and 4; β1b-Gly32-CaM was made by swapping β2a (M80545)44 with β1b (NM_017346.1)45 via KpnI and NotI sites, and was used in experiments for Figs 3h and 5.

FRET constructs were fluorescent tagged (either Venus or Cerulean) using standard PCR cloning techniques13. Briefly, Venus46 and Cerulean47 fluorophores (a kind gift from Dr Steven Vogel at NIH) were subcloned into pcDNA3 via unique KpnI and NotI sites. The PCR-amplified channel peptides20 were then cloned in via unique NotI and XbaI sites. The fluorescent-tagged peptides were PCR amplified as a whole and cloned into pAdLox via KpnI and EcoRI.

To make the Venus-PKAca-P2A-PKAr2b-Cerulean construct, Cerulean was PCR amplified and cloned into pcDNA3 via XbaI/ApaI and then PKAr2b (Addgene: pDONR223-PRKAr2b) was PCR amplified (the P2A sequence, FQGPGATNFSLLKQAGDVEENPGPSLSK, was fused 5′ of PRAr2b by this PCR amplification) and cloned via NotI/XbaI. PKAca (Addgene: pDONR223-PRKACA) was first cloned into Venus-C1 (made by replacing EGFP by Venus in pEGFP-C1)33. The Venus-PKAca was then PCR amplified and cloned into pcDNA3 containing P2A-PKAr2b-Cerulean via KpnI/NotI. The PKAca-P2A-PKAr2b (no fluorescent tag) was PCR amplified using Venus-PKAca-P2A-PKAr2b-Cerulean as a template and inserted into pcDNA3 via KpnI and XbaI. See Supplementary Table 3 for primer sequences.

Adenovirus production

Adenoviral vectors were generated using the Cre-Lox recombination system48. pAdLox plasmids encoding the FRET binding partners were co-transfected with Ψ5 vector into Cre8 cells49 (a kind gift from Dr David C. Johns), allowing expression and packaging of the viral particles. After three rounds of expansion in Cre8 cells, a final viral amplification was done in HEK293 cells (ATCC). The viral particles were collected and purified by a standard CsCl gradient protocol. The purified viral stock had a titre of at least 1012 particles per microlitre.

aGPVM culture and infection

Adult guinea pig ventricular myocytes (aGPVMs) were isolated from adult Hartley guinea pigs (either gender, 3–4 weeks old, weight 250–350 g) via Langendorff perfusion30. All procedures performed were in compliance with the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Following isolation, myocytes were plated on laminin-coated glass coverslips in M199 media containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS). After 1 h, media was exchanged with 0% FBS M199 media and adenoviruses encoding FRET binding partners were added. Eight to 12 h later, the myocytes were washed once with warmed PBS and the media was replaced with fresh 0% FBS media. aGPVMs were imaged within 24 h of isolation.

Transfection of HEK293 cells

For electrophysiology experiments, HEK293 cells (ATCC) were cultured on 10-cm plates and channels were transiently transfected by a calcium phosphate protocol12. Briefly, DNA was combined with 125 mM CaCl2 in a HEPES buffered saline solution and allowed to precipitate for 15 min. The DNA precipitate solution was then slowly added to cells and allowed to incubate for 3–5 h before solution exchange. We applied 4–16 μg of plasmid DNA encoding the desired α1-subunit, as well as 6–8 μg of β and 5–8 μg of rat α2δ (NM012919.2)50 subunits along with 3 μg of SV40 T antigen. For forskolin incubation experiments, β2a without a glycine-linked CaM was used. In addition, 4 μg Venus-PKAca-P2A-PKAr2B-Cerulean and 1 μg PKAr2b-Cerulean were co-transfected. For dynamic forskolin wash-on experiments, a β-subunit (β2a for CaV1.3 and 1.4; β1b for CaV1.2) with glycine-linked CaM was used. In addition, 4 μg Venus-PKAca-P2A-PKAr2b-Cerulean, 1 μg PKAr2b-Cerulean and 3 μg AKAP79 (M90359.1) were co-transfected. AKAP79 is known to bind to PKA and participate in PKA regulation in primary cells26 and is included specifically to prevent dialysis of the PKA in whole-cell experiments. In general, β2a was chosen to minimize the confounding effects of voltage-dependent inactivation, thus maximizing the dynamic range of CDI. For CaV1.2 channels, β1b was used to closely recapitulate the behaviour of the native CaV1.2 channel expressed in cardiac cells. By decreasing the dynamic range of observable CDI, this perturbation also increased the stringency of the test and allowed for comparison with native PKA modulation of CaV1.2 channels (Supplementary Fig. 5).

For microscope-based FRET assays, HEK293 cells cultured on 3.5-cm culture dishes with integral No. 0 glass coverslip bottoms (In Vitro Scientific) were transiently transfected with polyethylenimine reagent (Polysciences). For flow-cytometer-based FRET assays, HEK293T cells cultured on six-well plates were transiently transfected with polyethylenimine. All of constructs were driven by a cytomegalovirus promoter. Experiments were performed 1–2 days following transfection.

Whole-cell electrophysiology recording

Whole-cell recordings were obtained at either room temperature or 30 °C as described, using a TC-10 heating and cooling temperature controller (Dagon Corporation) and Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments). Electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Word Precision Instruments), with 1–3 MΩ resistances, which were in turn compensated for series resistance by >60%. Currents were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz before digital acquisition at five times the frequency. A P/8 leak-subtraction protocol was used. The internal solution contained (in mM): CsMeSO3, 114; CsCl, 5; MgATP, 4; HEPES pH 7.4, 10; and BAPTA (1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane- N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid), 10; at 295 mOsm adjusted with CsMeSO3. The bath solution was (in mM): TEA-MeSO3, 102; HEPES pH 7.4, 10; CaCl2 or BaCl2, 40; at 305 mOsm adjusted with TEA-MeSO3.

Microscope-based FRET optical imaging

FRET two-hybrid experiments were performed on an inverted microscope13,51. Briefly, total fluorescence from single cells, as isolated via pinhole in the image plane, was quantified by a photo-multiplier tube. The bath Tyrode's solution was (in mM): NaCl, 138; KCl, 4; MgCl2, 1; HEPES pH 7.4, 10; CaCl2, 2; at 305 mOsm adjusted with glucose. Filter cubes (excitation, dichroic, emission and company): CFP (D440/20X, 455DCLP, D480/30M, Chroma); YFP (500AF25, 525DRLP, 530ALP, Omega Optical); and FRET (D436/20X, 455DCLP, D535/30M, Chroma). The YFP signal was measured directly by excitation/emission through the YFP cube, thus was used as a gage for nonspecific fluorophore quenching or movement artefacts. FRET changes were determined via the CFP and FRET cubes13,51. Background fluorescent signals were measured from cells without expression of the fluorophores, which was particularly important for experiments in aGPVMs due to higher autofluorescence. In HEK cells, concentration-dependent spurious FRET was subtracted from the raw data before binding-curve analysis13,51. Cerulean and Venus were used as the donor and acceptor fluorescent proteins instead of cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), as their optical properties are better for this application.

Acceptor-centric measurements of FRET were obtained with the 33-FRET algorithm13,51, which expresses the effective FRET efficiency (Eeff) and FR as:

|

where  is the FRET efficiency of a donor–acceptor pair,

is the FRET efficiency of a donor–acceptor pair,  is the fraction of acceptor molecules bound by a donor.

is the fraction of acceptor molecules bound by a donor.  is the approximate molar extinction coefficients of Cerulean and Venus, which was measured as 0.08 on our setup.

is the approximate molar extinction coefficients of Cerulean and Venus, which was measured as 0.08 on our setup.

Analysis was done using a previously described binding model13,51 as follows. A 1:1 ligand-binding model is assumed to determine two parameters, FRmax and Kd,EFF. FRmax is the maximum FR that occurs when all acceptor-tagged molecules are bound; hence, FRmax depends only on inter-fluorophore geometry. The second parameter Kd,EFF, the effective dissociation constant, furnishes the relative dissociation constant for the binding reaction, with conversion factors to actual Kd determined by optical characteristics of our microscope system. Dfree is the relative concentration of free donor molecules. All parameters determined for each construct in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Flow-cytometer-based FRET optical imaging

FRET two-hybrid experiments were performed on an Attune Acoustic Focusing Cytometer (Life Technologies)33. Cells were trypsinized and resuspended in Tyrode's solution before loading onto the flow cytometer. Optical bandpass filters used for CFP, YFP and FRET were 450/40, 530/30 and 522/31 nm, respectively. Cells were illuminated for 40 μs at each excitation wavelength. The above algorithm (equation (1))13,51 was used to calculate acceptor-centric measures. In total, signals from 1,000–10,000 cells were recorded; however, only 30–50 randomly selected cells were displayed, to improve clarity of the figure. Flow-cytometer-based FRET correlated precisely with the microscope-based FRET33, but afforded much greater throughput. Parameters pertaining to the flow-cytometer-based FRET assay are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Mass spectroscopy

Double polyhistidine (His8)-tagged Cerulean-ICDI1.4 peptides were co-transfected with PKA holoenzyme in HEK293T cells. Cells were incubated in 50 μM forskolin in a 37 °C incubator for 1 h before collecting with a lysis buffer, containing (in mM): KCl, 20; K-gluconate, 120; MgCl2, 2; EGTA, 0.2; HEPES pH 7.4; Na2-ATP, 2; dithiothreitol, 10; cAMP, 0.1. Protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, complete, EGTA-free) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 and 3 (Sigma-Aldrich) were added into the lysis buffer according to the standard protocol. His-tagged Cerulean-ICDI1.4 peptides were purified by Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) and verified by SDS–PAGE using mini-PROTEAN precast gel (Bio-Rad). The band containing the ICDI1.4 peptide (Supplementary Fig. 7a) was cut from the gel then sent to the Johns Hopkins Mass Spectroscopy and Proteomics Facility, where the peptides were in-gel proteolysed with trypsin and analysed on nano-liquid chromatography electrospray ionization/tandem mass spectrometry Orbi-trap Velos in high resolution Fourier transform mode. Tandem MS2 mass spectra were processed by Proteome Discoverer (v1.4 Thermo Fisher Scientific) in three ways, using three Nodes: common, Xtract (spectra were extracted, charge state deconvoluted and deisotoped using Xtract option) and MS2 Processor. The tandem mass spectra were searched against the RefSeq2014 Human database filtered at a 1% false dicovery rate using PEAKS 7.0 (Bioinformatics Solutions Inc.). Variable modifications by M oxidation, NQ deamidation and STY phosphorylation were searched for with a precursor ion tolerance of 10 p.p.m. and a fragment ion tolerance of 0.02 Da.

Two peptides (peptide 1: GSADSLVEAVLISEGLGLFAR and peptide 2: LTLDEMDNAASDLLAQGTSSLYSDEESILSR) from CaV1.4 were identified, which covered 52% of the total 100 amino acids in ICDI1.4 (Supplementary Fig. 6d) and 11 of the 14 potential phosphorylation sites in this region. Three potential sites, T1872, S1874 and S1877, were not covered due to the limitation of trypsin, but they are not in the core region for IQ interaction28. Peptide 1 was identified nine times, among which it carried a phosphate group six times. The peaks from double and triple charged peptides detected in the first MS showed a molecular weight that was 79.97 Da higher than that expected without a phosphate group, verifying phosphorylation. The data predicted that either S1883 or S1886 could be the site of phosphorylation. However, the existence of b4, b4(–98) and y17 in the spectra in (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 7b) strongly suggested that the phosphorylation site is S1883. In addition, pkaPS predictions and mutagenesis (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 6) strongly support that the PKA phosphorylation site is S1883. Peptide 2 was identified 12 times and carried a phosphate group at S1942 in only 1 trial. This potential phosphorylation site, however, did not have any effect on the interaction between IQ1.3 and ICDI1.4 in our FRET binding assay (Supplementary Fig. 6c,d).

Creating a robust and controllable PKA system in HEK293 cells

Although PKA regulation of the IQ1.3/ICDI1.4 interaction was easily observed in aGPVMs (Supplementary Fig. 3b,c), the same regulation was absent in HEK293 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a), until the PKA holoenzyme (both the regulatory and catalytic subunits) was overexpressed (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Based on this evidence, we hypothesized that the expression level of PKA is lower in HEK293 cells than aGPVMs. Thus, the PKA holoenzyme was overexpressed in most of our experiments in HEK293 cells.

The delicately balanced expression of regulatory and catalytic subunits of PKA in native systems cannot be easily achieved by standard heterologous expression, as co-transfection of both subunits results in mixed basal PKA activity. To mimic the endogenous expression of native systems and guarantee low basal PKA activity, the overexpressed regulatory subunits would have to slightly outnumber the overexpressed catalytic subunit. To achieve this, we linked the catalytic and regulatory subunits by a viral-based 2A sequence from porcine tescho virus (P2A) optimized and characterized in a previous study52. The P2A sequence causes a self-hydrolysis reaction at the translation level, resulting in complete dissociation and close to 1:1 stoichiometry of the linked subunits. A small amount of extra regulatory subunit (1 μg per 4 μg holoenzyme) was co-expressed with this P2A construct to guarantee that the regulatory subunit always slightly outnumbered the catalytic subunit in each cell.

To test our system, we used the FRET-based PKA activity sensor AKAR4 (ref. 53). First, we expressed AKAR4 in HEK293 cells and measured the FRET efficiency (Eeff) of each cell by a flow cytometry assay. At this endogenous PKA expression level, most cells exhibited low PKA activity, as illustrated by the low Eeff of AKAR4, whereas a small percentage of cells showed high basal PKA activity (Supplementary Fig. 9). When PKA holoenzyme was expressed as described above, every cell had minimal basal PKA activity. In addition, when the cAMP level was elevated by adding 50 μM forskolin, PKA activity was saturated in all cells, indicated by the high Eeff of AKAR4 (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Finally, recording for forskolin wash-on experiments was done at a temperature of 30 °C, which was determined to be a necessary condition for robust PKA modulation (Supplementary Fig. 4). Of note, increasing the temperature from 23 °C to 30 °C significantly increased the extent of PKA modulation achieved by a 30-min incubation with forskolin and increasing the temperature from 30 °C to 37 °C further enhanced modulation (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, the PKA process for ICDI1.4 interaction with the channel IQ domain is much slower than many traditional PKA-mediated processes. The slow onset of PKA modulation fits well with the time course of channel regulation achieved by enriching CaM at the membrane via a rapamycin-based system14 and may represent a time course that is physiologically relevant in the visual system, where dopamine drives PKA slowly according to the circadian rhythm10,54.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sang, L. et al. Protein kinase A modulation of CaV1.4 calcium channels. Nat. Commun. 7:12239 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12239 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-9, Supplementary Tables 1-3 and Supplementary References.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of our advisor Dr David T. Yue. He was a caring and inspirational mentor who will live in our hearts forever. We thank Dr Nancy Yue, Dr Gordon Tomaselli and Dr King-Wai Yau for generous support and advice. We thank Wanjun Yang for dedicated technical support, Dr Hojjat Bazzazi for the original β2a-Gly8-CaM construct and Dr Rosy Joshi-Mukherjee for the help with the isolation of aGPVMs. We are grateful to Dr Manu Ben-Johny and other members of the Calcium Signals Lab for valuable comments and suggestions. We also thank the JHU SOM Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core, Hopkins Digestive Basic and Translational Research Core Center (NIDDK centre grant P30 DK089502) for their support with the mass spectroscopy experiments, and Dr. Robert Cole and Robert O'Meally for generous assistance in writing the manuscript. This work is supported by grants from the NHLBI and NINDS (to D.T.Y.).

Footnotes

Author contributions D.T.Y. and L.J.S. designed and refined the experiments and hypothesis. L.J.S. performed the experiments and carried out extensive analysis. I.E.D. contributed to the experiments in aGPVMs. L.J.S. and I.E.D. wrote the paper.

References

- Nishi H., Hashimoto K. & Panchenko A. R. Phosphorylation in protein-protein binding: effect on stability and function. Structure 19, 1807–1815 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey R. D. & Hell J. W. CaV1.2 signaling complexes in the heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 58, 143–152 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. F., Gutierrez L. M., Mundina-Weilenmann C. & Hosey M. M. Dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels from skeletal muscle. II. Functional effects of differential phosphorylation of channel subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 16395–16400 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall D. D. et al. Critical role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring to the L-type calcium channel Cav1.2 via A-kinase anchor protein 150 in neurons. Biochemistry 46, 1635–1646 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme J. T., Lin T. W., Westenbroek R. E., Scheuer T. & Catterall W. A. Beta-adrenergic regulation requires direct anchoring of PKA to cardiac CaV1.2 channels via a leucine zipper interaction with A kinase-anchoring protein 15. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13093–13098 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Blair L. A., Salinas G. D., Needleman L. A. & Marshall J. Insulin-like growth factor-1 modulation of CaV1.3 calcium channels depends on Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive stores and calcium/calmodulin kinase II phosphorylation of the alpha1 subunit EF hand. J. Neurosci. 26, 6259–6268 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRory J. E. et al. The CACNA1F gene encodes an L-type calcium channel with unique biophysical properties and tissue distribution. J. Neurosci. 24, 1707–1718 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemara-Wahanui A. et al. A CACNA1F mutation identified in an X-linked retinal disorder shifts the voltage dependence of Cav1.4 channel activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 7553–7558 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkovsky P. Dopamine and retinal function. Doc. Ophthalmol. Adv. Ophthal. 108, 17–40 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manglapus M. K., Iuvone P. M., Underwood H., Pierce M. E. & Barlow R. B. Dopamine mediates circadian rhythms of rod-cone dominance in the Japanese quail retina. J. Neurosci. 19, 4132–4141 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Johny M. et al. Towards a unified theory of calmodulin regulation (calmodulation) of voltage-gated calcium and sodium channels. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 8, 188–205 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B. Z., DeMaria C. D., Adelman J. P. & Yue D. T. Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+ -dependent inactivation of L- type calcium channels. Neuron 22, 549–558 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson M. G., Alseikhan B. A., Peterson B. Z. & Yue D. T. Preassociation of calmodulin with voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels revealed by FRET in single living cells. Neuron 31, 973–985 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams P. J., Ben-Johny M., Dick I. E., Inoue T. & Yue D. T. Apocalmodulin itself promotes ion channel opening and Ca(2+) regulation. Cell 159, 608–622 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B. Z. et al. Functional characterization of alternative splicing in the C terminus of L-type CaV1.3 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42725–42735 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock G. et al. Functional properties of a newly identified C-terminal splice variant of CaV1.3 L-type Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42736–42748 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan G. M. Y., Yu D. J., Wang J. J. & Soong T. W. Alternative splicing at C terminus of Ca(V)1.4 calcium channel modulates calcium-dependent inactivation, activation potential, and current density. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 832–847 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl-Schott C., Baumann L., Cuny H., Eckert C., Griessmeier K. & Biel M. Switching off calcium-dependent inactivation in L-type calcium channels by an autoinhibitory domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15657–15662 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. et al. C-terminal modulator controls Ca2+-dependent gating of CaV1.4 L-type Ca2+ channels. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1108–1116 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Yang P. S., Yang W. & Yue D. T. Enzyme-inhibitor-like tuning of Ca(2+) channel connectivity with calmodulin. Nature 463, 968–972 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani H. et al. Spontaneous and nicotine-induced Ca2+ oscillations mediated by Ca2+ influx in rat pinealocytes. Am. J. Physiol. J. Physiol. 306, C1008–C1016 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miriyala J., Nguyen T., Yue D. T. & Colecraft H. M. Role of CaVbeta subunits, and lack of functional reserve, in protein kinase A modulation of cardiac CaV1.2 channels. Circ. Res. 102, e54–e64 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S., Oz S., Benmocha A. & Dascal N. Regulation of cardiac L-type Ca(2)(+) channel CaV1.2 via the beta-adrenergic-cAMP-protein kinase A pathway: old dogmas, advances, and new uncertainties. Circ. Res. 113, 617–631 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F., Flockerzi V., Kahl S. & Wegener J. W. L-type CaV1.2 calcium channels: from in vitro findings to in vivo function. Physiol. Rev. 94, 303–326 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. E. Why has it taken so long to learn what we still don't know? Circ. Res. 113, 840–842 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diviani D., Dodge-Kafka K. L., Li J. & Kapiloff M. S. A-kinase anchoring proteins: scaffolding proteins in the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 301, H1742–H1753 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Johny M., Yang P. S., Bazzazi H. & Yue D. T. Dynamic switching of calmodulin interactions underlies Ca2+ regulation of CaV1.3 channels. Nat. Commun. 4, 1717 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang L., Bazzazi H., Ben Johny M. & Yue D. T. Resolving the grip of the distal carboxy tail on the proximal calmodulatory region of CaV channels. Biophys. J. 102, 126a–126a (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Colecraft H. M. et al. Novel functional properties of Ca(2+) channel beta subunits revealed by their expression in adult rat heart cells. J. Physiol. 541, 435–452 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi-Mukherjee R., Dick I. E., Liu T., O'Rourke B., Yue D. T. & Tung L. Structural and functional plasticity in long-term cultures of adult ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 65, 76–87 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadross M. R., Ben Johny M. & Yue D. T. Molecular endpoints of Ca2+/calmodulin- and voltage-dependent inactivation of Ca(v)1.3 channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 135, 197–215 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuberger G., Schneider G. & Eisenhaber F. pkaPS: prediction of protein kinase A phosphorylation sites with the simplified kinase-substrate binding model. Biol. Direct 2, 1 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. R., Sang L. & Yue D. T. Uncovering aberrant mutant PKA function with flow cytometric FRET. Cell Rep. 14, 3019–3029 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vonGersdorff H. & Matthews G. Calcium-dependent inactivation of calcium current in synaptic terminals of retinal bipolar neurons. J. Neurosci. 16, 115–122 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom T. M. et al. An L-type calcium-channel gene mutated in incomplete X-linked congenital stationary night blindness. Nat. Genet. 19, 260–263 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W. A. Regulation of cardiac calcium channels in the fight-or-flight response. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 8, 12–21 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z. et al. Protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of HERG potassium channels in a human cell line. Chin. Med. J. Peking 115, 668–676 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winklhofer A. et al. Analysis of phosphorylation-dependent modulation of Kv1.1 potassium channels. Neuropharmacology 44, 829–842 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Angelantonio S. et al. Adenosine A2A receptor induces protein kinase A-dependent functional modulation of human alpha 3 beta 4 nicotinic receptor. J. Physiol. Lond. 589, 2755–2766 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W. & Lipscombe D. Neuronal Ca(V)1.3alpha(1) L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J. Neurosci. 21, 5944–5951 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X. Y. et al. Heterologous regulation of the cardiac Ca2+ channel-alpha-1 subunit by skeletal-muscle beta-subunit and gamma-subunits - implications for the structure of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 21943–21947 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P. S., Ben Johny M. & Yue D. T. Allostery in Ca2+ channel modulation by calcium-binding proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 231–238 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M. X., Erickson M. G. & Yue D. T. Functional stoichiometry and local enrichment of calmodulin interacting with Ca2+ channels. Science 304, 432–435 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E. et al. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain beta subunit of the L- type calcium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 1792–1797 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pragnell M., Sakamoto J., Jay S. D. & Campbell K. P. Cloning and tissue-specific expression of the brain calcium channel beta-subunit. FEBS Lett. 291, 253–258 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T. et al. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 87–90 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo M. A., Springer G. H., Granada B. & Piston D. W. An improved cyan fluorescent protein variant useful for FRET. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 445–449 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alseikhan B. A., DeMaria C. D., Colecraft H. M. & Yue D. T. Engineered calmodulins reveal the unexpected eminence of Ca2+ channel inactivation in controlling heart excitation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 17185–17190 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S., Kitamura M., Harris-Stansil T., Dai Y. & Phipps M. L. Construction of adenovirus vectors through Cre-lox recombination. J. Virol. 71, 1842–1849 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson W. J. et al. Functional properties of a neuronal class C L-type calcium channel. Neuropharmacology 32, 1117–1126 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson M. G., Liang H., Mori M. X. & Yue D. T. FRET two-hybrid mapping reveals function and location of L-type Ca2+ channel CaM preassociation. Neuron 39, 97–107 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzazi H. et al. Novel fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based reporter reveals differential calcineurin activation in neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes. J. Physiol. 593, 3865–3884 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depry C., Allen M. D. & Zhang J. Visualization of PKA activity in plasma membrane microdomains. Mol. Biosyst. 7, 52–58 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribelayga C., Wang Y. & Mangel S. C. Dopamine mediates circadian clock regulation of rod and cone input to fish retinal horizontal cells. J. Physiol. 544, 801–816 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-9, Supplementary Tables 1-3 and Supplementary References.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.