Abstract

Resistance to antibiotics used against Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections is a major public health concern. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) testing relies on time-consuming culture-based methods. Development of rapid molecular tests for detection of AMR determinants could provide valuable tools for surveillance and epidemiological studies and for informing individual case management. We developed a fast (<1.5-h) SYBR green-based real-time PCR method with high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis. One triplex and three duplex reactions included two sequences for N. gonorrhoeae identification and seven determinants of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs), azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and spectinomycin. The method was validated by testing 39 previously fully characterized N. gonorrhoeae strains, 19 commensal Neisseria species strains, and an additional panel of 193 gonococcal isolates. Results were compared with results of culture-based AMR determination. The assay correctly identified N. gonorrhoeae and the presence or absence of the seven AMR determinants. There was some cross-reactivity with nongonococcal Neisseria species, and the detection limit was 103 to 104 genomic DNA (gDNA) copies/reaction. Overall, the platform accurately detected resistance to ciprofloxacin (sensitivity and specificity, 100%), ceftriaxone (sensitivity, 100%; specificity, 90%), cefixime (sensitivity, 92%; specificity, 94%), azithromycin (sensitivity and specificity, 100%), and spectinomycin (sensitivity and specificity, 100%). In conclusion, our methodology accurately detects mutations that generate resistance to antibiotics used to treat gonorrhea. Low assay sensitivity prevents direct diagnostic testing of clinical specimens, but this method can be used to screen collections of gonococcal isolates for AMR more quickly than current culture-based AMR testing.

INTRODUCTION

Gonorrhea is the second most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection worldwide, with an estimated 78 million new cases in 2012 (1). Moreover, Neisseria gonorrhoeae has developed resistance to most current and past treatment options. Antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) gonorrhea is a major public health concern about which the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the importance of global surveillance to identify emerging resistance, monitor trends, and inform revisions of treatment guidelines (2, 3).

At a molecular level, the mechanisms that confer resistance to the most common treatment options have been well characterized. For instance, the acquisition of mosaic penA alleles, with or without substitutions at amino acid position 501 of the encoded penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2), has been linked to decreased susceptibility or resistance to the extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) cefixime (CFX) and ceftriaxone (CRO) (4, 5). In particular, strains harboring a mosaic pattern XXXIV penA gene, including the internationally spreading N. gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence typing (NG-MAST) genogroup 1407, have been responsible for ESC treatment failures in several countries worldwide (5–8). The mutation A2059G or C2611T in the 23S rRNA alleles is associated with resistance to azithromycin (AZM) (9, 10), whereas a Ser91Phe substitution in GyrA results in ciprofloxacin (CIP) nonsusceptibility (11). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the 16S rRNA gene or in the ribosomal protein S5 (RPS5)-encoding gene rpsE (12, 13) confer spectinomycin (SPC) resistance. However, we note that while CIP-resistant N. gonorrhoeae isolates are frequently observed, isolates that are fully resistant to ESCs, AZM, and SPC are still found only sporadically (2, 14).

Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) has already replaced culture-based detection of N. gonorrhoeae in many settings, but these methods do not provide any information about AMR (16). On the other hand, antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) is usually performed with time-consuming culture methods (16). For this reason, there has been growing interest in the development of NAATs that can supplement culture-based AMR testing, enhance AMR surveillance, and ideally be used to tailor individualized treatment for gonorrhea patients (17).

Several nucleic acid amplification-based methods have been developed to identify the presence of SNPs (18). One of these techniques is high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis, which relies on the detection of changes in the melting temperature (Tm) resulting from the presence of mutations in a previously amplified target. This method is so sensitive that Tm shifts derived from even one SNP can be detected (19). Moreover, strategic target design (i.e., distinct Tms of the amplicons) also allows multiplexing of more than one reaction per tube (20). However, only multiple-step (e.g., requirement for additional steps after nucleic acid amplification for readout) (21, 22) or single-antibiotic (e.g., resistance to CIP only) NAAT-based methodologies to characterize AMR gonorrhea have been proposed in the past (23–28).

In this study, we developed and evaluated a new SYBR green-based real-time PCR method with HRM analysis to simultaneously detect N. gonorrhoeae and key mutations associated with ESC, AZM, CIP, and SPC resistance in four closed-tube multiplex reactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design of the real-time PCR assay.

Nine primer sets were designed with Oligo Primer Analysis software v4.0 (Molecular Biology Insights) to amplify specific sequences of the targets described in Table 1. Primers were designed to flank the mutation site of interest in the gyrA, 23S rRNA, 16S rRNA, and rpsE genes and to amplify penA mosaic sequences (e.g., pattern XXXIV) around codons 501 and 545. Additionally, GC clamps were added at the 5′ ends of some oligonucleotides to shift the Tm of the resulting amplicons in order to separate the peaks for easier interpretation of multiplex reaction results. The nine primer sets generated ∼40- to 140-bp products, all under the same conditions in both singleplex and multiplex reactions (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Target genes, primer sequences, amplicon lengths, mutations and affected antibiotics, and multiplex combinations for the real-time PCR platform

| Target | Primer (oligonucleotide sequence)a | Amplicon length (bp) | Associated target (purpose or antibiotic affected) | Multiplex type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| opa | opa_F (5′-GTTCATCCGCCATATTGTGTTGA-3′) | 56 | opa (species identification) | Triplex |

| opa_R (5′-AAGGGCGGATTATATCGGGTTCC-3′) | ||||

| porA | porA_F (5′-CAGCAATTTGTTCCGAGTCA-3′) | 44 | porA (species identification) | Triplex |

| porA_R (5′-GGCGTATAGGCGGACTTG-3′) | ||||

| penA Gly545Ser | 545_F (5′-CCCGCCCCCGCCGACTGCAAACGGTTACTA-3′) | 61 | Mosaic penA (decreased susceptibility/resistance to ESCs) | Triplex |

| 545_R (5′-CCCGCCCCCGCGGCCCTGCCACTACACC-3′) | ||||

| penA Ala501 | 501_F (5′-CCCGCCCCCGCCGTCGGCGCAAAAACCGGTACG-3′) | 79 | Mosaic penA (decreased susceptibility/resistance to ESCs) | Duplex I |

| 501_R (5′-CCCGCCCCCGCCAATCGACGTAACGACCGTTAACCAACTTACG-3′) | ||||

| 23S rRNA C2611T | C2611_F (5′-ACGTCGTGAGACAGTTTGGTC-3′) | 49 | 23S rRNA C2611T (moderate AZM resistance)b | Duplex I |

| C2611_R (5′-CAAACTTCCAACGCCACTGC-3′) | ||||

| 23S rRNA A2059G | A2059_F (5′-CTACCCGCTGCTAGACGGA-3′) | 142 | 23S rRNA A2059G (high-level AZM resistance)b | Duplex II |

| A2059_R (5′-CAGGGTGGTATTTCAAGGACGA-3′) | ||||

| gyrA Ser91Phe | gyrA_S91_F (5′-TAAATACCACCCCCACGGCGATT-3′) | 47 | GyrA Ser91Phe (CIP resistance) | Duplex II |

| gyrA_S91_R (5′-ATACGGACGATGGTGTCGTAAACT-3′) | ||||

| rpsE Thr24Pro | S5_T24_F (5′-ATGGTCGCAGTTAACCGTGTA-3′) | 56 | RPS5 Thr24Pro (SPC resistance) | Duplex III |

| S5_T24_R (5′-AAAGCCATAATGCGACCACC-3′) | ||||

| 16S rRNA C1192T | 16S_1192_F (5′-CCGCCCCCCGGAGGAAGGTGGGGATGA-3′) | 64 | 16S rRNA C1192T (SPC resistance) | Duplex III |

| 16S_1192_R (5′-CCGCCCCCCTGGTCATAAGGGCCATGAG-3′) |

GC clamps, which were added to the 5′ ends of some primers to allow multiplexing, are shown in italic type.

Confers moderate- to high-level resistance to AZM (i.e., MIC, >2 μg/ml) when at least 3 out of 4 copies are mutated (9).

N. gonorrhoeae isolates were grown on chocolate agar plates supplemented with PolyViteX (bioMérieux) for 24 h at 35°C in a humid 5% CO2-enriched atmosphere. Genomic DNA extraction was performed by using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen). Each 20-μl reaction mixture contained 0.3 μM each primer, 1× Meltdoctor master mix (Applied Biosystems), and 20 ng of genomic DNA (gDNA). Experiments were run with a QuantStudio 7 Flex instrument (Applied Biosystems). The PCR stage included a first denaturation step (95°C for 10 min), followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 15 s), annealing (62°C for 10 s), and extension (72°C for 10 s). After amplification, HRM analysis was performed by using the following parameters: after 10 s at 95°C and a 60°C hold for 1 min, the fluorescence signal was collected, while the samples were heated from 60°C to 95°C with a ramping time of 0.025°C/s. Results were analyzed with QuantStudio 6 and 7 Flex Real-Time PCR software v1.0 (Applied Biosystems). Overall, starting from extracted DNA templates, the results were available in <1.5 h (i.e., real-time PCR amplification for <60 min followed by HRM analysis for <30 min). To assess the limit of detection (LOD) of our molecular method, known quantities of gDNA copies/reaction were tested in 10-fold serial dilutions.

Neisseria species control strains.

A panel of 35 N. gonorrhoeae isolates was used to validate the real-time PCR method. The panel included 26 previously fully characterized isolates with known profiles of MICs and genetic resistance determinants (14); the fully sensitive reference strain ATCC 49226; WHO reference strains WHO K (carrying a mosaic pattern X penA gene), WHO L, WHO P, WHO O (SPC-resistant strain with a 16S rRNA C1192T mutation; MIC, >1,024 μg/ml), and WHO A (with a RPS5 Thr24Pro substitution; MIC, 128 μg/ml) (29); 2 AZM-resistant strains, AZM-HLR (harboring four 23S rRNA alleles with a A2059G mutation; MIC, ≥256 μg/ml) and G07 (harboring four 23S rRNA alleles with a C2611T mutation; MIC, 8 μg/ml); and ESC-resistant strain F89 carrying a mosaic pattern XXXIV penA gene with an additional mutation in codon 501 leading to an Ala501Pro substitution (MICs for CFX and CRO of 2 and 1.5 μg/ml, respectively) (5).

Nineteen nongonococcal Neisseria species strains identified previously by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Bruker Daltonik) were also used to assess cross-reactivity. The panel included N. meningitidis (n = 5), N. mucosa (n = 3), N. sicca (n = 2), N. cinerea (n = 2), N. lactamica (n = 2), N. subflava (n = 1), N. flava (n = 1), N. flavescens (n = 1), N. elongata (n = 1), and N. bacilliformis (n = 1) strains.

Analysis of representative spiked negative and positive samples.

Pharyngeal, rectal, and urethral clinical specimens were collected with ESwabs (Copan) and tested for N. gonorrhoeae by using an Aptima Combo 2 assay (Hologic). The QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen) was used to extract total DNA from 200 μl of ESwabs with positive or negative Aptima results. For the assessment of spiked negative specimens, 2 μl of sample DNA obtained from the ESwab was spiked with an additional 105, 104, or 103 gDNA copies of the appropriate control N. gonorrhoeae strain per reaction for each multiplex assay. For the positive specimens, 2 μl of sample DNA was used for each multiplex reaction. Culture isolates from the specimens were obtained by using standard microbiological methods, and species identification was achieved by using MALDI-TOF MS.

Analysis of gonococcal isolates and statistical analysis.

We analyzed 193 N. gonorrhoeae isolates collected during a 26-year period (1989 to 2014) in two microbiology laboratories located in Switzerland (Institute for Infectious Diseases, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, and Institute of Medical Microbiology, University Hospital Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland) with both culture-based AST and the new real-time PCR method.

Identification was achieved by using MALDI-TOF MS. MICs for CFX, CRO, CIP, AZM, and SPC were obtained on chocolate agar plates supplemented with PolyViteX (30) by using the Etest method (bioMérieux). MIC values for CFX, CRO, CIP, and SPC were categorized by using 2015 European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) criteria (31). For AZM, we defined moderate-level resistance and high-level resistance as MICs of >2 to 128 and ≥256 μg/ml, respectively, as previously reported (9).

Positive results from the real-time PCR assay (based on both amplification and melting temperature analyses) were interpreted as follows: (i) if opa and/or porA was detected, the strain was identified as N. gonorrhoeae; (ii) if penA encoding a Gly545Ser substitution and/or penA Ala501 was detected, the strain was considered resistant to CFX and/or CRO; (iii) if the 23S rRNA C2611T or A2059G mutation was detected, the strain was considered moderately or highly resistant to AZM, respectively; (iv) if gyrA encoding a Ser91Phe substitution was detected, the strain was considered nonsusceptible to CIP; and (v) if rpsE encoding a Thr24Pro substitution or 16S rRNA possessing a C1192T mutation was detected, the strain was considered resistant to SPC. Each sample was run in duplicate. Due to small interassay variabilities of the Tm values (Table 2), positive controls for each reaction (e.g., harboring the mutated AMR target sequence) were included to facilitate the interpretation of the results. Inconsistent results were confirmed by repetition of real-time PCR and PCR/DNA sequencing.

TABLE 2.

Results of method validation using 35 well-characterized N. gonorrhoeae isolatese

| Target | Sequence type result(s) for the 35 control isolates (no. of isolates with result) determined by: |

Tm (°C) |

Mean ΔTm ± SD (°C) | Sensitivityc (%) (95% CI) | Specificityc (%) (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA sequencing | Real-time PCR/HRM analysis | Range | Mean ± SD | ||||

| opa | Positive (35) | Positive (35) | 76.63–77.22 | 76.98 ± 0.13 | NA | 100 (90–100) | NAd |

| Negative (0) | Negative (0) | NA | NA | ||||

| porA | Positive (35) | Positive (35) | 73.79–74.88 | 74.36 ± 0.20 | NA | 100 (90–100) | NAd |

| Negative (0) | Negative (0) | NA | NA | ||||

| penA Gly545Ser | Nonmosaic (23) | Nonmosaic (23) | NAa | NAa | 100 (66–100) | 100 (87–100) | |

| Nonmosaic Gly545 (GGC) (3) | Nonmosaic Gly545 (GGC) (3) | 85.05–85.23a | 85.14 ± 0.08a | 0.46 ± 0.05 | |||

| Mosaic Gly545Ser (AGC) (9) | Mosaic Gly545Ser (AGC) (9) | 84.09–84.72 | 84.47 ± 0.20 | ||||

| penA Ala501 | Nonmosaic (26) | Nonmosaic (26) | NAb | NAb | 100 (66–100) | 100 (87–100) | |

| Mosaic (9) | Mosaic (9) | 83.59–84.35 | 84.17 ± 0.19 | NI | |||

| gyrA Ser91Phe | GyrA Ser91 (TCC), Ala92 (GCA) (11) | GyrA Ser91 (TCC), Ala92 (GCA) (11) | 77.97–78.16 | 78.08 ± 0.05 | 100 (86–100) | 100 (72–100) | |

| GyrA Ser91Phe (TTC), Ala92 (GCA) (23) | GyrA Ser91Phe (TTC), Ala92 (GCA) (23) | 77.29–77.59 | 77.47 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.06 | |||

| GyrA Ser91Phe (TTC), Ala92Ser (TCA) (1) | GyrA Ser91Phe (TCC), Ala92Ser (TCA) (1) | 76.15–76.17 | 76.16 ± 0.02 | 1.25 ± 0.01 | |||

| 23S rRNA A2059G | A2059 (34) | A2059 (34) | 81.33–81.52 | 81.44 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 100 (3–100) | 100 (90–100) |

| A2059G (1) | A2059G (1) | 81.61–81.70 | 81.67 ± 0.03 | ||||

| 23S rRNA C2611T | C2611 (34) | C2611 (34) | 75.69–76.33 | 76.12 ± 0.16 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | 100 (3–100) | 100 (90–100) |

| C2611T (1) | C2611T (1) | 75.08–75.55 | 75.30 ± 0.20 | ||||

| rpsE Thr24Pro | Thr24 (ACC) (34) | Thr24 (ACC) (34) | 73.87–74.34 | 74.08 ± 0.07 | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 100 (3–100) | 100 (90–100) |

| Thr24Pro (CCC) (1) | Thr24Pro (CCC) (1) | 74.66–74.94 | 74.76 ± 0.09 | ||||

| 16S rRNA C1192T | C1192 (34) | C1192 (34) | 81.38–81.72 | 81.56 ± 0.08 | 0.69 ± 0.01 | 100 (3–100) | 100 (90–100) |

| C1192T (1) | C1192T (1) | 80.74–80.94 | 80.82 ± 0.09 | ||||

Only nonmosaic pattern XIX (with penA Gly545) showed cross-amplification.

No amplification was observed for all other nonmosaic penA patterns tested.

Sensitivity is the probability that an isolate was correctly identified as being positive by HRM analysis for the target sequence (species identification, mosaic, or mutation); specificity is the probability that an isolate was correctly identified as being negative by HRM analysis for the target sequence (species identification, mosaic, or mutation).

Specificity was 100% considering that all 19 nongonococcal control strains were correctly characterized as non-N. gonorrhoeae isolates (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

NA, not applicable; NI, not interpretable.

For the 193 isolates, we calculated the sensitivity (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) of real-time PCR with HRM analysis for the detection of N. gonorrhoeae compared with MALDI-TOF MS, which was used as the reference standard. We calculated sensitivity (with the 95% CI) for the detection of AMR to each antibiotic class as the percentage of isolates with a nonsusceptible or resistant MIC value that were correctly identified by a positive HRM result for the presence of the correlated resistance determinant. We calculated specificity (with the 95% CI) as the percentage of isolates with a susceptible MIC value that were correctly identified by a negative HRM result for the correlated resistance determinant.

Since the 193 isolates detected in Switzerland did not include the rare strains possessing the mutations that confer resistance to CRO, AZM, and SPC, sensitivity and specificity were also calculated by including the results for the 35 N. gonorrhoeae control strains and 4 additional isolates provided by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Gonorrhoea and Other STIs (Örebro, Sweden). These four strains included ESC-resistant strain A8806 harboring a mosaic penA allele (MICs for CFX and CRO of 2 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively) (32); AZM-resistant strains GC2 (33) and GC4 harboring the C2611T (AZM MIC of 8 μg/ml) and A2059G (AZM MIC of ≥256 μg/ml) mutations in all four 23S rRNA alleles, respectively; and SPC-resistant strain GC3 harboring the 16S rRNA C1192T mutation (MIC for SPC of >z μg/ml).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

One triplex and three duplex reactions were designed to characterize target sequences specific for N. gonorrhoeae identification (opa and porA) (34, 35) as well as for resistance to ESCs (mosaic penA alleles), CIP (GyrA substitution), AZM (23S rRNA mutations), and SPC (16S rRNA mutation or RPS5 substitution) (Table 1).

Validation of the method and limit of detection.

As shown in Table 2, all 35 N. gonorrhoeae control strains were correctly identified by the positive amplification of both the opa and porA reactions; amplicons had average Tm values of 76.98°C and 74.36°C, respectively, by HRM analysis.

The penA reaction targeting the Gly545Ser mutation was relatively specific for mosaic penA patterns. Only nonmosaic pattern XIX was cross-amplified, but all N. gonorrhoeae strains harboring a mosaic penA allele (i.e., patterns XXXIV and X) were correctly identified by the presence of the Gly545Ser mutation, which caused a mean Tm shift of 0.46°C compared with that of the wild-type sequence. Additionally, the Ala501 reaction amplified only mosaic penA patterns, but we were not able to detect the mutation encoding the Ala501Pro substitution found in the ESC-resistant F89 strain (Table 2) (5). This was probably because third-class mutations (i.e., G-to-C SNPs) are known to be difficult to detect by HRM analysis, since the Tm shift resulting from such nucleotide substitutions is very small (15). Nevertheless, this reaction was still used for the detection of mosaic penA alleles.

HRM analysis correctly identified the presence or absence of mutations associated with resistance to CIP, AZM, and SPC (Table 2). Strains harboring the Ser91Phe substitution in GyrA generated discernible melting curves compared with those of the wild-type isolates, with a mean Tm difference (ΔTm) of 0.61°C. One strain (2121127) (14) harbored an additional mutation in codon 92, which caused a further shift in the Tm compared to that of the wild-type sequence (ΔTm = 1.25°C). Strains with mutation A2059G or C2611T in all four alleles of the 23S rRNA gene generated unique profiles compared with isolates harboring wild-type alleles, with mean ΔTm values of 0.22°C and 0.75°C, respectively. Strains harboring the target SNPs in the rpsE or 16S rRNA gene exhibited a mean Tm shift of 0.68°C to 0.69°C compared with that of the wild-type sequences (Table 2).

Finally, when 10-fold dilutions of 107 to 10 gonococcal gDNA copies/reaction were tested, a starting quantity of at least 103 to 104 gDNA copies was needed to allow proper HRM analysis in all four multiplex reactions (see examples in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This LOD is higher than that of available commercial platforms (e.g., according to the manufacturer, the Aptima Combo2 test claims an analytical sensitivity of 50 cells/assay).

Cross-reaction with nongonococcal Neisseria spp.

False-positive results for AMR targets due to the presence of nongonococcal Neisseria spp. commonly found in some specimen types (e.g., pharyngeal and rectal samples) is a major challenge for the design of NAAT-based diagnostic methods. In fact, several Neisseria spp. share with gonococcus high sequence similarity for some of the targets (e.g., 23S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes). Moreover, the N. gonorrhoeae mosaic penA allele is thought to be the result of horizontal gene transfer of the commensal orthologues (36, 37). Therefore, in order to assess the level of cross-reactivity for all nine genetic targets included in our multiplex real-time PCR platform, a panel of 10 different nongonococcal Neisseria species (overall, 19 strains) was tested.

As shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material, none of these strains showed positive amplification for opa and porA. This was expected, since both genetic regions were previously proven to be specific for N. gonorrhoeae (34, 35). The GyrA Ser91Phe reaction was also specific for N. gonorrhoeae. In contrast, several nongonococcal species showed cross-reactions for all remaining target sequences (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). In only a few cases could cross-amplification be distinguished from N. gonorrhoeae by a different Tm (i.e., 23S rRNA A2059G), but for most targets, the Tm of the amplified commensal target matched the expected Tm of the gonococcal wild-type sequence (e.g., 23S rRNA C2611 and 16S rRNA C1192). However, none of the cross-reacting species had a Tm equal to that of the mutated N. gonorrhoeae sequence for any of the targets, indicating that false-positive results derived from the presence of commensals are unlikely. Even in the presence of a positive penA A501 reaction, the absence of the Gly545Ser substitution allowed the differentiation of the gonococcal mosaic penA gene from its commensal counterpart in 3 strains, since this substitution is found mostly in genococcus. However, 2 N. meningitidis and 2 N. cinerea strains tested positive for a mosaic penA allele based on the positive penA Ala501 reaction. Moreover, excessive amounts of wild-type amplification due to commensal Neisseria spp. could potentially mask the presence of an AMR mutation in N. gonorrhoeae, especially in clinical specimens with low loads of the pathogen (i.e., in pharyngeal samples) (38, 39).

Analysis of representative spiked negative and positive samples.

To assess the extent of commensal interference in the detection of the AMR determinants in clinical specimens, four pharyngeal and four rectal samples negative for N. gonorrhoeae were spiked with gDNA of control strains possessing the mutations of interest for each multiplex reaction.

The results obtained from the pharyngeal specimens showed strong background amplification of wild-type amplicons due to the presence of Neisseria spp. for most target reactions (e.g., 23S rRNA C2611T, 16S rRNA C1192T, and rpsE Thr24Pro). This background amplification would cause false-negative results, especially in the presence of small amounts of gonococci. Additionally, nonspecific amplification strongly affected the melting curve interpretation of the gyrA Ser91Phe and 23S rRNA A2059G reactions. Finally, two samples exhibited positive amplification of the penA A501 reaction due to commensals (see examples in Fig. S2A to S2E in the supplemental material). On the other hand, for the spiked negative rectal specimens, strong cross-amplification of only wild-type 16S rRNA C1192 was observed (see examples in Fig. S3A to S3D in the supplemental material).

Taken together with the relatively high LOD needed for proper HRM analysis, these limitations suggested that our method would not be suitable for direct screening of clinical specimens. For this reason, total DNA extracted from four pharyngeal, four rectal, and four urethral clinical samples positive for N. gonorrhoeae was used to test the performance of our method. Results were also compared to the gDNA extracted from N. gonorrhoeae strains (when available) isolated from the specimens.

Our platform indicated that all four pharyngeal samples tested positive for the opa reaction (see Fig. S4A to S4D in the supplemental material). Cross-amplification of commensals together with the relatively low gonococcal load led to a false-positive result for the presence of mosaic penA in three samples. Additionally, the melting curves of several reactions were not properly interpretable due to low or nonspecific amplification (e.g., gyrA Ser91Phe, 23S rRNA A2059G, and rspE Thr24Pro). Similarly, small amplicon amounts strongly affected the melting curve interpretation of all four multiplex reactions in the positive rectal (see Fig. S5A to S5D in the supplemental material) and urethral (see Fig. S6A to S6D in the supplemental material) specimens, confirming that our method cannot be directly implemented for clinical specimens. Nonetheless, it could be a valuable tool for rapid screening of large isolate collections, for both surveillance and epidemiological purposes. For this reason, we compared our molecular methodology with the standard culture-based Etest method for AST of a panel of 193 Swiss isolates.

Analysis of the 193 clinical isolates.

As shown in Table 3, the real-time PCR platform correctly identified all isolates as N. gonorrhoeae. Moreover, AMR characterization for CIP had both sensitivity and specificity of 100%, whereas characterization for AZM and SPC had specificities of 100%. In particular, our method correctly identified all isolates exhibiting resistance to CIP (58 out of 58). No mutations associated with SPC resistance were observed, in agreement with the results obtained by phenotypic AST. Furthermore, none of the isolates tested positive for the 23S rRNA C2611T or A2059G mutation associated with moderate- or high-level AZM resistance, respectively. Consistently, none of the tested isolates exhibited AZM MICs of >2 μg/ml. Finally, all 7 strains showing CFX resistance by phenotypic AST were positive for the presence of a mosaic penA allele. However, no resistance to CRO was observed. This finding was expected, since it is known that the presence of a mosaic penA gene is typically associated with raised MICs for ESCs, even if they are usually still in the susceptible range based on EUCAST criteria (40).

TABLE 3.

Performance of the real-time PCR platform in characterizing the collection of 193 N. gonorrhoeae isolates alone and combined with the 39 N. gonorrhoeae control strainsg

| Phenotypic target | Target sequence(s) |

N. gonorrhoeae isolates collected during 1989–2014 (n = 193) |

All N. gonorrhoeae strains (n = 232), including 39 controls |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test result | No. of isolatesa | No. of isolates with AST resultb |

Sensitivityd (%) (95% CI) | Specificityd (%) (95% CI) | Test result | No. of strainsa,e | No. of isolates with AST resultb |

Sensitivityd (%) (95% CI) | Specificityd (%) (95% CI) | ||||

| S | R | S | R | ||||||||||

| Species identification | opa and/or porA | Positive | 193 | NA | NA | 100 (97–100) | NA | Positivee | 232 | NA | NA | 100 (98–100)e | 100 (82–100)e |

| Negative | — | Negativee | 19 | ||||||||||

| CRO | penA Gly545Ser and/or penA Ala501 | Positive | 16 | 16 | — | NA | 92 (87–95) | Positive | 26 | 24 | 2 | 100 (16–100) | 90 (85–93) |

| Negative | 177 | 177 | — | Negative | 206 | 206 | — | ||||||

| CFX | penA Gly545Ser and/or penA Ala501 | Positive | 16 | 9 | 7 | 100 (47–100) | 95 (91–98) | Positive | 26 | 14 | 12 | 92 (64–100) | 94 (90–96) |

| Negative | 177 | 177 | — | Negative | 206 | 205 | 1f | ||||||

| AZMc | 23S rRNA A2059G or 23S rRNA C2611T | Positive | — | — | — | NA | 100 (97–100) | Positive | 4 | — | 4 | 100 (40–100) | 100 (98–100) |

| Negative | 193 | 193 | — | Negative | 228 | 228 | — | ||||||

| CIP | gyrA Ser91Phe | Positive | 58 | — | 58 | 100 (91–100) | 100 (96–100) | Positive | 83 | — | 83 | 100 (96–100) | 100 (98–100) |

| Negative | 135 | 135 | — | Negative | 149 | 149 | — | ||||||

| SPC | rpsE Thr24Pro or 16S rRNA C1192T | Positive | — | — | — | NA | 100 (97–100) | Positive | 3 | — | 3 | 100 (29–100) | 100 (98–100) |

| Negative | 193 | 193 | — | Negative | 229 | 229 | — | ||||||

Numbers are based on the results of the multiplex real-time PCR platform.

AST was categorized based on EUCAST criteria with the exception of AZM (see below).

AZM resistance was defined as an MIC of >2 μg/ml.

Sensitivity was the probability that an isolate categorized as being resistant was identified as positive by real-time PCR; specificity was the probability that an isolate categorized as being sensitive was identified as negative by real-time PCR.

For the evaluation of “species identification,” we also included the 19 nongonococcal Neisseria species strains.

Strain WHO L (nonmosaic penA gene with an additional mutation encoding the Ala501Val amino acid substitution).

AST, antimicrobial susceptibility testing by Etest; R, resistant; S, susceptible; CI, confidence interval; —, zero; NA, not applicable.

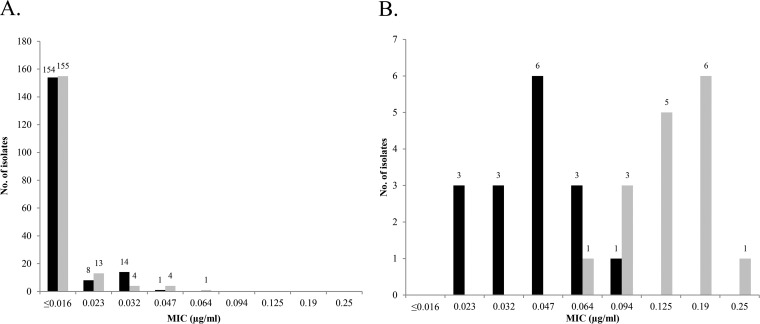

Thus, we further explored the MIC distribution of CFX and CRO in isolates harboring mosaic or nonmosaic penA patterns (Fig. 1). Out of the 16 isolates positive for the presence of a mosaic penA allele, 7 were CFX resistant, and 5 were only a 2-fold dilution (MIC, 0.125 μg/ml) lower than the resistance cutoff. The remaining four strains with a mosaic penA gene had raised CFX MICs of 0.064 to 0.094 μg/ml, whereas all other nonmosaic isolates tested exhibited MICs of ≤0.047 μg/ml. Furthermore, all 16 strains harboring a mosaic penA allele also showed raised CRO MICs in the range of 0.023 to 0.094 μg/ml, which were noticeably higher than those of strains with nonmosaic patterns, in agreement with previously reported observations (37, 40, 41).

FIG 1.

Distribution of ceftriaxone (black bars) and cefixime (gray bars) MICs for the 193 gonococcal isolates. (A) Isolates harboring a nonmosaic penA gene (n = 177); (B) isolates carrying a mosaic penA gene (n = 16).

Overall performance of the real-time PCR platform.

Since some of the resistance mutations were not included among the 193 Swiss isolates, we also evaluated the performance of our test by including the 35 control strains and 4 additional isolates harboring known, but very rare, AMR determinants (Table 3).

Our platform accurately identified N. gonorrhoeae with sensitivity and specificity of 100%. However, strain GC2 tested positive for the opa reaction only. Notably, this strain was previously reported to cause false-negative results in other porA-based PCRs due to the acquisition of a meningococcal porA allele (33). For this reason, our dual-target approach proved to be extremely valuable for the identification of even such exceptional isolates.

With regard to AMR detection, the platform correctly predicted resistance to ciprofloxacin in all 83 strains positive for a mutation in codon 91 of gyrA. Furthermore, the prediction of a mosaic penA allele allowed the detection of two fully CRO-resistant strains (F89 and A8806) as well as all isolates that were resistant to CFX with the exception of WHO L, which harbors a nonmosaic penA allele with an additional mutation encoding the Ala501Val amino acid substitution. It is worth noting that the mosaic penA allele of A8806 differs from the pattern XXXIV allele found in the high-level CRO-resistant F89 strain. For this reason, no amplification of the penA Gly545Ser target was observed for A8806. Nevertheless, the strain was correctly identified as harboring a mosaic penA allele due to the positive penA Ala501 reaction. Finally, the identification of either of the two mutations conferring resistance to AZM or SPC was correctly associated with resistance to these antibiotics.

Conclusions.

We developed and validated a new real-time PCR method coupled with HRM analysis that accurately detected several important mutations associated with resistance to antibiotics commonly used to treat gonorrhea. Cross-reactivity with commensal species and the high limit of detection suggested that our method is not suitable for direct screening of clinical specimens. However, it proved to be a useful and rapid alternative to culture-based methods to assess the AMR profiles for ESCs, AZM, CIP, and SPC for a large collection of N. gonorrhoeae isolates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the SwissTransMed initiative (Translational Research Platforms in Medicine, project number 25/2013: Rapid Diagnosis of Antibiotic Resistance in Gonorrhoea [RaDAR-Go]) from the Rectors' Conference of the Swiss Universities (CRUS).

We thank Reinhard Zbinden and Martina Marchesi, who provided the isolates from the University Hospital Zurich, and Joost Smid, who did the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.03354-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, Stevens G, Gottlieb S, Kiarie J, Temmerman M. 2015. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 10:e0143304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unemo M, Shafer WM. 2011. Antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: origin, evolution, and lessons learned for the future. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1230:E19–E28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. 2012. Global action plan to control the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohnishi M, Watanabe Y, Ono E, Takahashi C, Oya H, Kuroki T, Shimuta K, Okazaki N, Nakayama S, Watanabe H. 2010. Spread of a chromosomal cefixime-resistant penA gene among different Neisseria gonorrhoeae lineages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1060–1067. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01010-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unemo M, Golparian D, Nicholas R, Ohnishi M, Gallay A, Sednaoui P. 2012. High-level cefixime- and ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in France: novel penA mosaic allele in a successful international clone causes treatment failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1273–1280. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05760-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dam AP, van Ogtrop ML, Golparian D, Mehrtens J, de Vries HJ, Unemo M. 2014. Verified clinical failure with cefotaxime 1g for treatment of gonorrhoea in the Netherlands: a case report. Sex Transm Infect 90:513–514. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unemo M, Golparian D, Potocnik M, Jeverica S. 2012. Treatment failure of pharyngeal gonorrhoea with internationally recommended first-line ceftriaxone verified in Slovenia, September 2011. Euro Surveill 17(25):pii=20200 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unemo M, Golparian D, Stary A, Eigentler A. 2011. First Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with resistance to cefixime causing gonorrhoea treatment failure in Austria, 2011. Euro Surveill 16(43):pii=19998 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chisholm SA, Dave J, Ison CA. 2010. High-level azithromycin resistance occurs in Neisseria gonorrhoeae as a result of a single point mutation in the 23S rRNA genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3812–3816. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00309-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng LK, Martin I, Liu G, Bryden L. 2002. Mutation in 23S rRNA associated with macrolide resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3020–3025. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.3020-3025.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shultz TR, Tapsall JW, White PA. 2001. Correlation of in vitro susceptibilities to newer quinolones of naturally occurring quinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains with changes in GyrA and ParC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:734–738. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.734-738.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigmund CD, Ettayebi M, Morgan EA. 1984. Antibiotic resistance mutations in 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA genes of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 12:4653–4663. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.11.4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ilina EN, Malakhova MV, Bodoev IN, Oparina NY, Filimonova AV, Govorun VM. 2013. Mutation in ribosomal protein S5 leads to spectinomycin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Front Microbiol 4:186. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Endimiani A, Guilarte YN, Tinguely R, Hirzberger L, Selvini S, Lupo A, Hauser C, Furrer H. 2014. Characterization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates detected in Switzerland (1998-2012): emergence of multidrug-resistant clones less susceptible to cephalosporins. BMC Infect Dis 14:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liew M, Pryor R, Palais R, Meadows C, Erali M, Lyon E, Wittwer C. 2004. Genotyping of single-nucleotide polymorphisms by high-resolution melting of small amplicons. Clin Chem 50:1156–1164. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.032136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiley DM, Tapsall JW, Sloots TP. 2006. Nucleic acid amplification testing for Neisseria gonorrhoeae: an ongoing challenge. J Mol Diagn 8:3–15. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Low N, Unemo M, Skov Jensen J, Breuer J, Stephenson JM. 2014. Molecular diagnostics for gonorrhoea: implications for antimicrobial resistance and the threat of untreatable gonorrhoea. PLoS Med 11:e1001598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson NJ. 2006. The use of real-time PCR methods in DNA sequence variation analysis. Clin Chim Acta 363:32–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vossen RH, Aten E, Roos A, den Dunnen JT. 2009. High-resolution melting analysis (HRMA): more than just sequence variant screening. Hum Mutat 30:860–866. doi: 10.1002/humu.21019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seipp MT, Pattison D, Durtschi JD, Jama M, Voelkerding KV, Wittwer CT. 2008. Quadruplex genotyping of F5, F2, and MTHFR variants in a single closed tube by high-resolution amplicon melting. Clin Chem 54:108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balashov S, Mordechai E, Adelson ME, Gygax SE. 2013. Multiplex bead suspension array for screening Neisseria gonorrhoeae antibiotic resistance genetic determinants in noncultured clinical samples. J Mol Diagn 15:116–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawung R, Cherdtrakulkiat R, Charoenwatanachokchai A, Nabu S, Suksaluk W, Prachayasittikul V. 2009. One-step PCR for the identification of multiple antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Microbiol Methods 77:323–325. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magooa MP, Muller EE, Gumede L, Lewis DA. 2013. Determination of Neisseria gonorrhoeae susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in clinical specimens from men using a real-time PCR assay. Int J Antimicrob Agents 42:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao L, Zhao S. 2012. TaqMan real-time quantitative PCR assay for detection of fluoroquinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Curr Microbiol 65:692–695. doi: 10.1007/s00284-012-0212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siedner MJ, Pandori M, Castro L, Barry P, Whittington WL, Liska S, Klausner JD. 2007. Real-time PCR assay for detection of quinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in urine samples. J Clin Microbiol 45:1250–1254. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01909-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Yokoi S, Kawamura Y, Maeda S, Ezaki T, Deguchi T. 2002. Rapid detection of quinolone resistance-associated gyrA mutations in Neisseria gonorrhoeae with a LightCycler. J Infect Chemother 8:145–150. doi: 10.1007/s101560200025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindback E, Rahman M, Jalal S, Wretlind B. 2002. Mutations in gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE in quinolone-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. APMIS 110:651–657. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2002.1100909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buckley C, Trembizki E, Donovan B, Chen M, Freeman K, Guy R, Kundu R, Lahra MM, Regan DG, Smith H, Whiley DM, GRAND Study Investigators . 2016. A real-time PCR assay for direct characterization of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae GyrA 91 locus associated with ciprofloxacin susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:353–356. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unemo M, Fasth O, Fredlund H, Limnios A, Tapsall J. 2009. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the 2008 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strain panel intended for global quality assurance and quality control of gonococcal antimicrobial resistance surveillance for public health purposes. J Antimicrob Chemother 63:1142–1151. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-fifth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S25. CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 31.EUCAST. 2015. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters, version 5.0. http://www.eucast.org/.

- 32.Lahra MM, Ryder N, Whiley DM. 2014. A new multidrug-resistant strain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Australia. N Engl J Med 371:1850–1851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1408109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golparian D, Johansson E, Unemo M. 2012. Clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolate with a N. meningitidis porA gene and no prolyliminopeptidase activity, Sweden, 2011: danger of false-negative genetic and culture diagnostic results: Euro Surveill 17(9):pii=20102 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabrizi SN, Chen S, Tapsall J, Garland SM. 2005. Evaluation of opa-based real-time PCR for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sex Transm Dis 32:199–202. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000154495.24519.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whiley DM, Buda PJ, Bayliss J, Cover L, Bates J, Sloots TP. 2004. A new confirmatory Neisseria gonorrhoeae real-time PCR assay targeting the porA pseudogene. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 23:705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka M, Nakayama H, Huruya K, Konomi I, Irie S, Kanayama A, Saika T, Kobayashi I. 2006. Analysis of mutations within multiple genes associated with resistance in a clinical isolate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced ceftriaxone susceptibility that shows a multidrug-resistant phenotype. Int J Antimicrob Agents 27:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ameyama S, Onodera S, Takahata M, Minami S, Maki N, Endo K, Goto H, Suzuki H, Oishi Y. 2002. Mosaic-like structure of penicillin-binding protein 2 gene (penA) in clinical isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3744–3749. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3744-3749.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knapp JS, Hook EW III. 1988. Prevalence and persistence of Neisseria cinerea and other Neisseria spp. in adults. J Clin Microbiol 26:896–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bissessor M, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, Danielewski J, Whitton B, Bird S, Garland S, Chen MY. 2011. Differing Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterial loads in the pharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men: implications for gonococcal detection, transmission, and control. J Clin Microbiol 49:4304–4306. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05341-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindberg R, Fredlund H, Nicholas R, Unemo M. 2007. Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with reduced susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone: association with genetic polymorphisms in penA, mtrR, porB1b, and ponA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:2117–2122. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01604-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osaka K, Takakura T, Narukawa K, Takahata M, Endo K, Kiyota H, Onodera S. 2008. Analysis of amino acid sequences of penicillin-binding protein 2 in clinical isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone. J Infect Chemother 14:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.