Abstract

Polymyxins are antibiotics used in the last line of defense to combat multidrug-resistant infections by Gram-negative bacteria. Polymyxin resistance arises through charge modification of the bacterial outer membrane with the attachment of the cationic sugar 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose to lipid A, a reaction catalyzed by the integral membrane lipid-to-lipid glycosyltransferase 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose transferase (ArnT). Here, we report crystal structures of ArnT from Cupriavidus metallidurans, alone and in complex with the lipid carrier undecaprenyl phosphate, at 2.8 and 3.2 angstrom resolution, respectively. The structures show cavities for both lipidic substrates, which converge at the active site. A structural rearrangement occurs on undecaprenyl phosphate binding, which stabilizes the active site and likely allows lipid A binding. Functional mutagenesis experiments based on these structures suggest a mechanistic model for ArnT family enzymes.

Polymyxins are last-resort antibiotics used to combat multidrug-resistant infections by Gram-negative bacteria (1, 2). They are thought to act by permeabilizing the membranes of Gram-negative bacteria, after binding to the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of the outer membrane (1, 2). This association with the outer membrane is primarily achieved through electrostatic interactions between amino groups of polymyxins and negatively charged moieties of the backbone glucosamine and 3-deoxy-D-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo) sugars of lipid A, an amphipathic saccharolipid that anchors LPS to the outer leaflet of the outer membrane (3). Resistance to polymyxins develops through active modifications of lipid A, which cap the glucosamine sugar phosphates and thus reduce negative membrane charge (4). Lipid A modification is also relevant for evasion of naturally occurring cationic antimicrobial peptides by Gram-negative bacteria (5, 6).

In Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica, the most effective modification for reduction of negative membrane charge is the attachment of the cationic sugar 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose (L-Ara4N) to lipid A phosphate groups at the 1 and 4′ positions (7). L-Ara4N is provided by the lipid carrier undecaprenyl phosphate (UndP). The reaction is catalyzed on the periplasmic side of the inner membrane by ArnT (PmrK), an integral membrane lipid-to-lipid glycosyltransferase and the last enzyme in the aminoarabinose biosynthetic pathway of Gram-negative bacteria (4, 7, 8) (Fig. 1A). The lipid A 1-phosphate group is also modified by EptA (PmrC), which adds phosphoethanolamine (pEtN), competing with ArnT for the 1-phosphate site (9, 10).

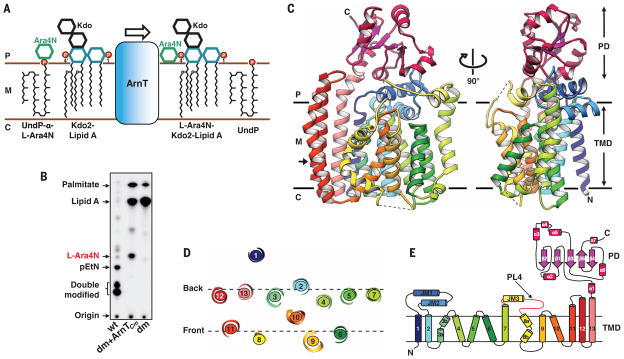

Fig. 1. Structure and function of ArnT from Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34.

(A) Schematic representation of the reaction catalyzed by ArnT. The sugar L-Ara4N is transferred from the carrier UndP to lipid A. 1 and 4′ phosphate positions on lipid A are marked. (B) Analysis of 32P-labeled lipid A species by TLC showing rescue of lipid A modification with L-Ara4N when ArnTCm is expressed in the ΔarnTΔeptA double-knockout E. coli strain (dm). The background E. coli strain (WD101; wt, wild type) has a pmrA constitutive phenotype (pmrAC), enabling it to synthesize L-Ara4N- and pEtN-modified lipid A and to exhibit resistance to polymyxins (8). (C) Crystal structure of ArnTCm. Two orthogonal views, perpendicular to the plane of the membrane, are presented in ribbon representation with rainbow coloring starting from the N terminus (blue) to the C terminus (purple). The approximate dimensions of the monomer are 55,79, and 42 Å (width, height, and depth). Membrane boundaries shown were calculated using the PPM server (21). Dashed lines represent missing segments in the structure. (D) Arrangement of TM helices in ArnTCm shown as a slice of the TM domain at the level indicated by the arrow in (C). (E) Schematic representation of the connectivity and structural elements of ArnTCm. P, periplasm; M, membrane (inner); C, cytoplasm; TMD:TM domain; PL4 (shown in red).

To gain insight into the structure and mechanistic basis of ArnT function, we screened 12 prokaryotic putative ArnTs from diverse species to find a candidate for crystallization (11). ArnT from Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 (ArnTCm) emerged as the most promising based on expression levels (fig. S1A) and behavior in size-exclusion chromatography in detergent (fig. S1B). This protein yielded crystals in lipidic cubic phase (LCP) (12) (fig. S1, C and D) that were suitable for structure determination.

We characterized ArnTCm to determine whether it was a true ArnT capable of transferring L-Ara4N to lipid A. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) of 32P-labeled lipid A isolated from E. coli showed that heterologous expression of ArnTCm in an E. coli strain lacking endogenous arnT and eptA (ΔarnTΔeptA) resulted in lipid A modification by L-Ara4N (Fig. 1B). The identity of the transferred sugar was confirmed by mass spectrometry (fig. S2A). Unlike ArnT from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (ArnTSe), ArnTCm failed to rescue resistance to polymyxin in ΔarnT (13, 14) (fig. S2B) and in ΔarnTΔeptA (fig. S2C) E. coli strains. Although it is known that ArnTSe adds L-Ara4N to both the 1 and 4′ phosphates of lipid A (7), ArnTCm appears only to yield a single lipid A species modified at the 1-phosphate position (fig. S2D), which suggests that modification at the 1-position does not confer protection to polymyxin in E. coli. Consistent with this, removal or modification of the 4′-phosphate confers polymyxin resistance in other species (15, 16). Therefore, functional hypotheses derived from the structures of ArnTCm were tested on ArnTSe by using a polymyxin growth assay previously established in E. coli (13, 14) and with a direct assay on ArnTCm for some mutants. The overall sequence identity between ArnTSe and ArnTCm is 23%, but the degree of conservation in and around the key regions for activity is substantially higher, which suggests that their structure and function are likely conserved (fig. S3).

The structure of ArnTCm was determined to 2.8 Å resolution by the single-wavelength anomalous diffraction method using SeMet-substituted protein (fig. S4 and Table 1). ArnTCm is a monomer, consisting of a transmembrane (TM) domain and a soluble periplasmic domain (PD) positioned above it (Fig. 1C). The TM domain, demarcated by a clear hydrophobic belt (fig. S5A), shows 13 TM helices, as recently predicted for ArnT from Burkholderia cenocepacia (17), in an intricate arrangement (Fig. 1, D and E). The structure has three juxtamembrane (JM) helices (JM1 to JM3). JM1 and JM2 are both part of the first periplasmic loop and are perpendicular to each other, creating a distinctive cross-shaped structure (Fig. 1C). JM3 leads into a flexible periplasmic loop between TM7 and TM8 [periplasmic loop 4 (PL4), partially disordered in the structure], previously shown to be functionally important (13, 17). TM13 leads into the PD, which has an α/β/α arrangement (Fig. 1E).

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics for ArnT.

I/σ(I), the empirical signal-to-noise ratio; CC1/2, a correlation coefficient; N/A, not applicable; h, k, and l, indices that define the lattice planes; Rmeas, multiplicity-corrected R, Rpim, expected precision; RMS, root mean square; clashscore is a validation tool in Phenix; TLS, translation/libration/screw, a mathematical model. Note that the apo data set was collected from crystals grown in the presence of decaprenyl phosphate. The presence of this compound in the crystallization mix does not lead to the conformational change observed in the ligand-bound form (see Materials and Methods).

| apo | bound (UndP) | SeMet | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.979 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 46.2–2.7 (2.8–2.7) | 47.9–3.2 (3.3–3.2) | 75.5–3.3 (3.4–3.3) |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit cell: a, b, c (Å) | 58.60, 80.63, 150.25 | 59.65, 80.32, 150.16 | 58.91, 81.21, 151.63 |

| Total reflections | 554,931 (41,515) | 89,964 (8,386) | 265,697 (25,867) |

| Unique reflections | 20,239 (2,000) | 12,427 (1,212) | 11,387 (1,120) |

| Multiplicity | 27.4 (20.8) | 7.2 (6.9) | 23.3 (23.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.8 (99.5) | 100 (99.9) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 25.5 (0.9) | 5.6 (1.3) | 11.4 (2.4) |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 65.2 | 63.8 | 81.5 |

| Rmerge | 0.38 (3.5) | 0.37 (1.9) | 0.23 (1.3) |

| Rmeas | 0.39 (3.6) | 0.40 (2.0) | 0.23 (1.3) |

| Rpim | 0.075 (0.767) | 0.144 (0.748) | 0.048 (0.271) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.218) | 0.994 (0.468) | 1.000 (0.839) |

| Resolution where I/σ(I) > 2.0 (overall) | 2.83 | 3.40 | N/A |

| Resolution where I/σ(I) > 2.0 (along h) | 2.92 | 3.20 | N/A |

| Resolution where I/σ(I) > 2.0 (along k) | 2.70 | 4.11 | N/A |

| Resolution where I/σ(I) > 2.0 (along l) | 2.84 | 3.58 | N/A |

| Resolution where CC1/2 >0.5 (overall) | 2.86 | 3.20 | N/A |

| Resolution where CC1/2 >0.5 (along h) | 2.81 | 3.20 | N/A |

| Resolution where CC1/2 >0.5 (along k) | 2.83 | 3.85 | N/A |

| Resolution where CC1/2 >0.5 (along l) | 2.94 | 3.36 | N/A |

| Refinement | |||

| Reflections used in refinement | 20,239 (1,962) | 12,427 (1,208) | N/A |

| Reflections used for Rfree | 1047 (96) | 668 (59) | N/A |

| Rwork | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.22 (0.32) | N/A |

| Rfree | 0.26 (0.42) | 0.26 (0.38) | N/A |

| Number of nonhydrogen atoms | 4,562 | 4,804 | N/A |

| Macromolecules | 4,097 | 4,171 | N/A |

| Ligands | 431 | 627 | N/A |

| Protein residues | 537 | 541 | N/A |

| RMS (bonds) | 0.003 | 0.002 | N/A |

| RMS (angles) | 0.56 | 0.49 | N/A |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97 | 96 | N/A |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 2.8 | 3.7 | N/A |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0 | 0.2 | N/A |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0.5 | 0.5 | N/A |

| Clashscore | 4.25 | 4.96 | N/A |

| Average B-factor | 75.8 | 50.6 | N/A |

| Macromolecules | 74.4 | 49.5 | N/A |

| Ligands | 89.6 | 57.4 | N/A |

| Solvent | 65.1 | 44.2 | N/A |

| Number of TLS groups | 2 | 2 | N/A |

ArnT is a member of the GT-C family of glycosyltransferases (18), and it has a similar fold to a bacterial oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) from Campylobacter lari (PglB) and to an archaeal OST from Archaeoglobus fulgidus (AglB) (19, 20) (fig. S6A). The topology differs among the three (fig. S6B), but an inner core of AglB’s TM domain aligns well with that of ArnTCm (fig. S6C) and a part of the PDs of ArnTCm and PglB is similar (fig. S6, D and E). These similarities in fold may underscore an evolutionary relationship, but the functions of the three enzymes are markedly different. Only ArnT has a lipid as glycosyl acceptor (lipid A). Because both substrates are lipidic, ArnT must bring both from the membrane to the active site for catalysis.

The structure of ArnTCm shows three major cavities (Fig. 2, A and B), which differ in their electrostatic nature. The largest (>3000 Å3 within the membrane), cavity 1, is amphipathic with a lower, primarily hydrophobic portion located below the level of the membrane and an upper hydrophilic one (fig. S5B). We hypothesize that cavity 1 is where lipid A binds to ArnT. Note that the hydrophobic portion of cavity 1 is directly accessible from the outer leaflet of the inner membrane, and it has a volume compatible with the acyl chains and the glucosamine sugar backbone of lipid A. This suggests a simple mechanism for lipophilic substrate recruitment, although entrance to cavity 1 may be occluded by PL4 (Fig. 2, A and B). The Kdo sugars of lipid A could bind to the hydrophilic upper portion of the cavity and possibly interact with the PD. The smaller cavity 2, connected to cavity 1 through a narrow passage, is primarily hydrophilic, despite its position, at least in part, below the boundary of the membrane (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S5B). Finally, cavity 3, located close to the cytoplasmic side of the molecule is entirely hydrophobic (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S5B).

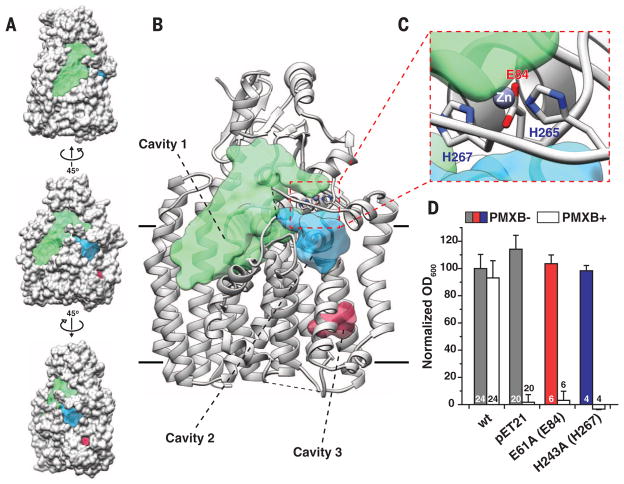

Fig. 2. Significant structural features of ArnTCm.

(A) Three views of ArnTCm in spacefill representation showing the location of notable cavities in the structure. The middle view has the same orientation as the view in (B). The other two are obtained by 45° rotation in opposite directions around a vertical axis. Cavities are color coded as in (B), where their identity is labeled. (B) Ribbon representation of ArnTCm showing the volumes of notable cavities in the structure. Volumes were calculated using the Voss Volume Voxelator server (22), using probes with 15 and 1.75 Å radii, corresponding to the outer and inner probe, respectively. The approximate membrane boundaries are shown as black lines. (C) Close-up of the metal coordination site in ArnTCm showing Zn+2 as a purple sphere and the coordinating residues colored by heteroatom. The dashed red line box in (B) shows the overall location of the coordination site. (D) The effect of mutations in Zn+2 coordinating residues on ArnTSe expressed in a BL21(DE3)ΔarnT E. coli strain for rescue of polymyxin B (PMXB) resistance (13). Corresponding residue numbers in ArnTCm are shown in parentheses here and in all subsequent figures. OD600, optical density at 600 nm. Data presented are means + SD. N is shown for each data column.

ArnTCm binds a metal we identified as Zn between JM1 and PL4 (Fig. 2C and fig. S7). The Zn2+ ion is bound with a five-point trigonal bipyramidal coordination by glutamic acid at position 84 (E84) (bidentate), histidines H265 and H267, and likely by a water molecule (Fig. 2C), replaced in our crystals by the carboxyterminal carbonyl from a symmetry-related molecule (fig. S7B). All three metal-coordinating residues appear to be important for function, as shown by the lack of polymyxin resistance in ArnTSe when mutated (Fig. 2D) (13). However, H265 is a valine (V241) in ArnTSe (fig. S3A), and therefore, its metal coordination must differ.

To investigate how ArnT interacts with its lipid substrates, we cocrystallized ArnTCm with UndP by incorporating this hydrophobic compound into the LCP mixture, and we determined the structure to 3.2 Å resolution (Table 1). The ArnTCm-UndP structure features three discontinuous densities compatible with a polyprenyl ligand, which allowed us to model the entire carrier lipid (Fig. 3A and fig. S8). The upper density (Fig. 3A), stemming from inside cavity 2, corresponds to the phosphate head group and five prenyl groups and defines the approximate location of the active site within the hydrophilic cavity 2 (Fig. 3B). The lower region of density (Fig. 3A), corresponding to the last four prenyls of UndP, extends from cavity 3, which is lined with hydrophobic residues that provide an ideal environment for accommodating the lipid tail (Fig. 3C). Mutations within cavity 3 had only a marginal effect on ArnTSe function (fig. S9). These results may indicate flexibility of the UndP binding mode away from the active site.

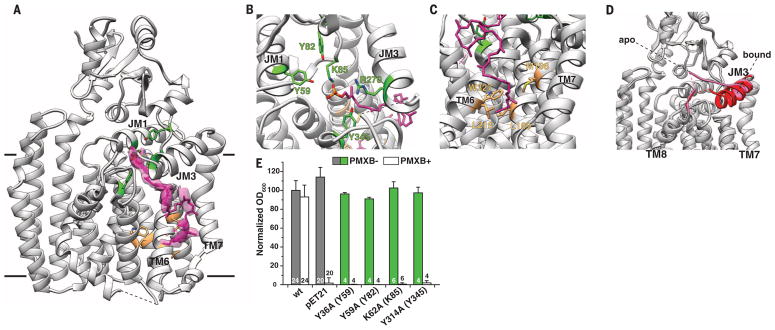

Fig. 3. Binding of undecaprenyl phosphate (UndP) to ArnTCm.

(A) Ribbon representation of the 3.2 Å resolution crystal structure of ArnTCm in complex with UndP. UndP was modeled based on densities present for the head group and tail of the molecule. The electron densities shown are from a 2Fobs – Fcalc omit map for the UndP contoured at 1 root mean square deviation (RMSD). (B) Close-up of the head group, with residues tested for functional significance shown in stick representation and colored by location (green for cavity 2) and heteroatom. (C) Close-up of the tail of UndP inserted into cavity 3. Residues shown in stick representation and colored by location (tan for cavity 3) and heteroatom have been tested for functional significance (see fig. S9). (D) Superposition of the apo and UndP-bound structures, where PL4 is colored pink for the apo structure and red for the UndP-bound state. The rearrangement of coil (apo) to helix (bound) shown here is the only substantial change between the two structures. (E) Functional significance of residues around the head group of UndP, tested by using a polymyxin B (PMXB) growth assay (13). Data presented are means + SD. N is shown for each data column.

Notably, in the UndP-bound structure, we observed a structural rearrangement of PL4. A coil-to-helix transition results in an extension of JM3 by two full turns, which leads to a repositioning of several residues around UndP and the apparent loss of metal coordination (Fig. 3, A and D). The nature of Zn2+ coordination is consistent with a role in fixing the loop in a conformation that allows the UndP substrate to bind. The conformation observed in the UndP-bound structure substantially reduces the volume of cavity 2, as the extension of JM3 envelopes the head of the substrate (fig. S10). Furthermore, although the volume of cavity 1 is only marginally changed, the UndP-mediated structural rearrangement enables displacementofPL4 from the cavity1 surface, which may enable access to lipid A (fig. S10).

The phosphate of UndP is coordinated by lysine K85 and arginine R270, whereas the oxygen of the phosphodiester bond participates in hydrogen bonding with tyrosine Y345 (Fig. 3B). These three residues are absolutely conserved (fig. S11), and their mutation in ArnTSe leads to complete loss of function (Fig. 3E) (13). A sulfate ion identified in the structure of AglB and proposed to occupy the position of the UndP phosphate (20), is superimposable with the phosphate of UndP in our structure (fig. S12), which suggests a common modality for donor substrate orientation.

Naïve docking of L-Ara4N-tri-prenyl phosphate to the ArnTCm structure yielded a highly populated pose with favorable energy and positions that matched the experimentally observed UndP (fig. S13). This pose revealed three additional conserved residues (Y59, Y82 and E506) that are likely to interact with L-Ara4N. We confirmed the importance of Y59 and Y82 in ArnTSe function (Fig. 3E). Residues corresponding to Y59, K85, R270, and E506, have been shown to be functionally relevant in ArnT from B. cenocepacia (17). E84, which coordinates Zn2+ in apo ArnTCm, appears to bind the amino group of L-Ara4N, which suggests a possible role for this residue in transitioning to the substrate-bound form. In ArnTCm, E84A was also inactive (fig. S14).

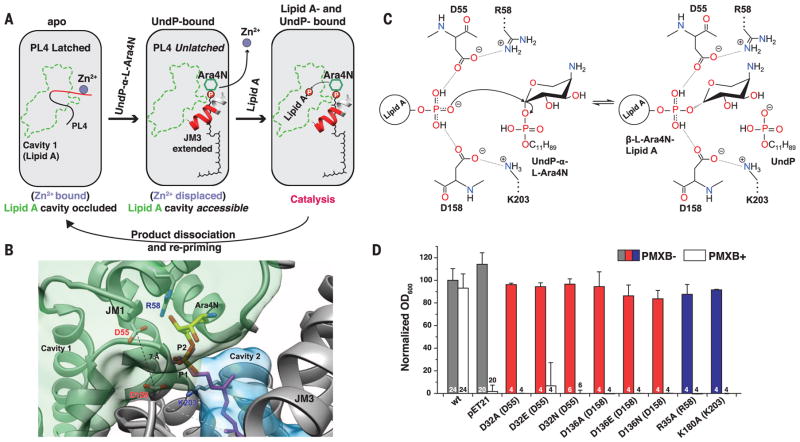

Overall, the structures of ArnTCm suggest that the binding of substrates may be sequential, with UndP-α-L-Ara4N binding stabilizing a conformation accessible to lipid A (Fig. 4A). The active site, situated between the two substrate cavities, is completed by elements of the extended JM3 helix only with UndP bound (Fig. 4, A and B). The structure with bound UndP and modeled L-Ara4N is consistent with a catalytic mechanism in which two conserved aspartic acid residues, D55 and D158, located at the interface between cavities 1 and 2 (Fig. 4B) and engaged in salt bridges with conserved positively charged residues (R58 and K203, respectively), play a critical role in orienting the lipid A phosphate for a nucleophilic attack on the L-Ara4N donor (Fig. 4C). Indeed, mutations of D55 and D158 in ArnTCm, and of any of the equivalent residues involved in these two ion pairs in ArnTSe, led to loss of activity (Fig. 4D and fig. S14). This work provides a structural framework for understanding the function of the ArnT family of enzymes, which may inform the design of compounds targeted at reversing resistance to polymyxin-class antibiotics.

Fig. 4. Putative catalytic mechanism of ArnT.

(A) Schematic representation of substrate-binding–induced conformational changes and catalytic cycle of ArnTCm. The boundaries of cavity 1 are shown in green, and the loop (PL4) that rearranges upon UndP binding is in red. (B) Structural perspective of the active site of ArnTCm. A putative position for the aminoarabinose sugar determined by docking is shown. The conserved D55 and D158 are located at the interface between the binding site for UndP-L-Ara4N and cavity 1, and have a Cγ-Cγ distance of 7.1 Å. P1 (magenta) is the phosphate of experimentally determined UndP, whereas P2 (heteroatom) is the phosphate from the modeled L-Ara4N-phosphate. (C) Putative catalytic mechanism in which two of the oxygen atoms of the acceptor phosphate are coordinated by D55 and D158, which leaves the third with a net negative charge, primed for a direct nucleophilic attack on the arabinose ring. This mechanism is consistent with inversion of the glycosidic bond, as reported for L-Ara4N attachment to lipid A (23). A precedent for a phosphate acting as a nucleophile exists (24). R58 and K203 appear to act similarly as the catalytic Mg2+, in the case of PglB, that localizes the charge of an aspartate and a glutamate, which in turn coordinate the nucleophile acceptor amide (19, 25). (D) Function of putative catalytic aspartates D32 and D136 and positively charged residues R35 and K180 in ArnTSe tested utilizing the PMXB growth assay (13). Data presented are means + SD. N is shown for each data column.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Crystallographic data for this study were collected at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines 24ID-C and E, supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), NIH, grant P41 GM103403, at the Advanced Photon Source. The Pilatus 6M detector on 24-ID-C beam line is funded by an Office of Research Infrastructure High-End Instrumentation, NIH, grant S10 RR029205. This work was supported by an NIGMS initiative to the New York Consortium on Membrane Protein Structure (NYCOMPS; U54 GM095315) and by NIGMS grant R01 GM111980 (F.M.). Also acknowledged are NIH grants AI064184 and AI076322 (M.S.T.), and grant W911NF-12-1-0390 from the Army Research Office (M.S.T.). O.B.C. was supported by a Charles H. Revson Senior Fellowship. We thank W. Hendrickson for his leadership of NYCOMPS and continuous support and advice, A. Palmer and P. Loria for helpful discussions, and L. Hamberger for her assistance managing the Mancia laboratory. PDB accession codes: 5EZM (apo ArnTCm) and 5F15 (UndP-bound ArnTCm).

Footnotes

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Zavascki AP, Goldani LZ, Li J, Nation RL. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:1206–1215. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landman D, Georgescu C, Martin DA, Quale J. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:449–465. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mares J, Kumaran S, Gobbo M, Zerbe O. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11498–11506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806587200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raetz CRH, Reynolds CM, Trent MS, Bishop RE. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brogden KA. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Needham BD, Trent MS. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:467–481. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43122–43131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trent MS, et al. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43132–43144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrera CM, Hankins JV, Trent MS. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:1444–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H, Hsu FF, Turk J, Groisman EA. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4124–4133. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4124-4133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancia F, Love J. J Struct Biol. 2010;172:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caffrey M. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:29–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Impellitteri NA, Merten JA, Bretscher LE, Klug CS. Biochemistry. 2010;49:29–35. doi: 10.1021/bi901572f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bretscher LE, Morrell MT, Funk AL, Klug CS. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;46:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cullen TW, et al. PLOS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002454. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, McGrath SC, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9321–9330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600435200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tavares-Carreón F, Patel KB, Valvano MA. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10773. doi: 10.1038/srep10773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lairson LL, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, Withers SG. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061005.092322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lizak C, Gerber S, Numao S, Aebi M, Locher KP. Nature. 2011;474:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:17868–17873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309777110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomize MA, Pogozheva ID, Joo H, Mosberg HI, Lomize AL. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D370–D376. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voss NR, Gerstein M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server):W555–W562. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Z, Ribeiro AA, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13542–13551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thoden JB, Holden HM. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1379–1388. doi: 10.1110/ps.072864707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lizak C, et al. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2627. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.