Abstract

Background

Europe has a growing population of ethnic minority groups whose dietary behaviours are potentially of public health concern. To promote healthier diets, the factors driving dietary behaviours need to be understood. This review mapped the broad range of factors influencing dietary behaviour among ethnic minority groups living in Europe, in order to identify research gaps in the literature to guide future research.

Methods

A systematic mapping review was conducted (protocol registered with PROSPERO 2014: CRD42014013549). Nine databases were searched for quantitative and qualitative primary research published between 1999 and 2014. Ethnic minority groups were defined as immigrants/populations of immigrant background from low and middle income countries, population groups from former Eastern Bloc countries and minority indigenous populations. In synthesizing the findings, all factors were sorted and structured into emerging clusters according to how they were seen to relate to each other.

Results

Thirty-seven of 2965 studies met the inclusion criteria (n = 18 quantitative; n = 19 qualitative). Most studies were conducted in Northern Europe and were limited to specific European countries, and focused on a selected number of ethnic minority groups, predominantly among populations of South Asian origin. The 63 factors influencing dietary behaviour that emerged were sorted into seven clusters: social and cultural environment (16 factors), food beliefs and perceptions (11 factors), psychosocial (9 factors), social and material resources (5 factors), accessibility of food (10 factors), migration context (7 factors), and the body (5 factors).

Conclusion

This review identified a broad range of factors and clusters influencing dietary behaviour among ethnic minority groups. Gaps in the literature identified a need for researchers to explore the underlying mechanisms that shape dietary behaviours, which can be gleaned from more holistic, systems-based studies exploring relationships between factors and clusters. The dominance of studies exploring ‘differences’ between ethnic minority groups and the majority population in terms of the socio-cultural environment and food beliefs suggests a need for research exploring ‘similarities’. The evidence from this review will feed into developing a framework for the study of factors influencing dietary behaviours in ethnic minority groups in Europe.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12966-016-0412-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Diet, Food habits, Dietary behaviour, Ethnic minority groups, Europe, Migrants, Immigrants, Factors, Determinants

Background

During the last few decades, migration in Europe has increased and many immigrant-origin groups have been reported to have a higher prevalence of diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and poorer dietary habits than the native born European populations [1, 2]. In addition, Europe has a number of indigenous minority groups such as the Sami and the Roma, who have historically suffered from discrimination and marginalization accompanied by diet-related NCDs [3]. Given the rise in ethnic minority groups and the high prevalence of NCDs among these populations [4], a clear understanding of factors influencing dietary behaviour is warranted in order to assess the needs of these populations and to develop effective public health interventions that also reach ethnic minority groups.

Dietary behaviours have been found to vary widely among and within different ethnic minority groups compared to host populations [5], indicating that factors influencing dietary behaviour may differ in ethnic minority populations as compared to the majority population [6]. However, most studies have focused either on a selected number of ethnic minority groups or are limited to specific European countries [7, 8]. For instance, research in the UK has focused on South Asians [9] and African Caribbeans [7] and in the Netherlands the focus has been on Surinamese [10]. This emphasis is also reflected in reviews of dietary behaviours; a 2008 review focused specifically on dietary change among the largest ethnic minority groups in Europe [11], whilst two reviews concentrated only on ethnic minority groups in the UK [5] and France [12]. Indigenous minorities have not been included in any reviews. Thus there is a lack of insight into the broad range of factors influencing dietary behaviour among a wide range of ethnic minority groups in Europe. In addition, there has been little attempt to study factors influencing dietary behaviour in a holistic way. In the obesity foresight map [13] for instance, the complexity of factors driving dietary behaviours are illustrated, but this was not prepared through the lens of ethnic minority populations.

This review fills these gaps by systematically reviewing primary studies on a wide range of ethnic minority groups and by considering a variety of dietary behaviours over the whole life course, using a holistic and data driven approach, by clustering emerging factors across these groups. The aims of this review were to identify the broad range of factors influencing dietary behaviour among ethnic minority groups living in Europe in order to identify gaps in the literature to guide future research. The evidence from this review will also feed into developing a framework for the study of factors influencing dietary behaviours in ethnic minority groups in Europe [14], as part of the work of the DEDIPAC-KH (DEterminants of DIet and Physical Activity Knowledge Hub) [15] for European populations.

Review

Review typology

A systematic mapping review [16] of the factors influencing dietary behaviour among ethnic minority groups in Europe was conducted. A mapping review was selected because it allows the mapping and categorisation of existing literature and identification of the gaps in research literature [16]. To avoid research bias during the review process, the review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (PROSPERO 2014: CRD42014013549) before commencing.

Search strategy

An initial scoping search was undertaken through PubMed PubReMiner [17] with the aim of assessing the amount of available literature and identifying appropriate search terms to be used in the main searches. A search strategy was constructed in consultation with information specialists from the University of Sheffield and the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam. The search strategy was based on search terms within three concepts: (i) dietary behaviours and its synonyms: diet, food habits, nutritional status, food preferences and nutrition; (ii) ethnic minority groups; and (iii) all countries that are listed by the World Bank as low and middle income countries. In addition, countries from the former Eastern European Bloc [18] from where groups commonly migrate to other parts of Europe, were included so that the review captured all ethnic minority groups living in Europe including indigenous populations. Other search terms that were used to capture potential studies were: emigrants, immigrants, cultural diversity, minority groups, migrants, ethnic groups, multiculturalism, ethnic minority, BME (Black and Minority Ethnic), black, minority ethnic, asylum seeker, refugee, non-white, coloured population or black; and (iii) Europe, all European countries by name. The search strategy contained free text and subject headings.

The following nine electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, ProQuest, Psychinfo, ASSIA, and Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews. The search strategy was modified where necessary for use in different electronic databases. The complete MEDLINE search strategy is shown in Additional file 1.

Databases were searched from 1999 to 2014, as it was expected that any factor identified before 1999 would also be referred to in more recent literature. Spot checks on results from the scoping review indicated that key papers emerged after 1999. Searches were conducted between May and July 2014. The citation follow–up technique and contacting of experts in the field was undertaken to identify additional relevant articles. In addition, the reference lists of all included articles were scanned for articles that met the inclusion criteria. All citations were downloaded into an Endnote web library and duplicates were removed.

Ethnic minority population is a concept used for very heterogeneous groups that may share minority status in their country of residence due to ethnicity, place of birth, language, religion, citizenship as well as other cultural differences [19]. This definition may include groups from newly arrived immigrants to (minority) groups that have been part of a country’s history, for instance the Sami people.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Observational and intervention studies, using quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods that examine dietary behaviour among ethnic minority groups in Europe were included. Other studies that focused on nutrition-related conditions, for example, obesity and contained relevant data on dietary behaviour in ethnic minority groups were also included. All studies that identified an association between a factor (including correlates, predictors, moderators, determinants and mediators) and dietary behaviour of minority groups living in Europe were retained.

All primary studies that analysed diet as a confounder in a relationship between ethnicity and disease were excluded. As were studies that explored whether ethnicity is a determinant of diet and did not attempt to explain why, non-human studies/laboratory based studies and studies examining beliefs and practices around breastfeeding and weaning. Studies examining the nutrient status of particular groups without mention of diet and studies presenting descriptive information about diet were also excluded.

Study selection

The title and abstracts of a total of 2965 articles identified references were imported into Endnote and 730 duplicates removed. The remaining 2235 articles were equally divided between five independent reviewers (HO, MN, KP, MH and LT) against the inclusion criteria. Of these abstracts, 1956 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. The main reasons for excluding studies were because they contained no empirical data on ethnic minority groups, presented only descriptive information on diet or where outside the review time limit. Full text articles were retrieved by the five reviewers for the remaining 279 articles and the inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied. This yielded 68 potentially relevant papers for data extraction. Spot checks were conducted on a sample of 10 % of the excluded papers to assess the extent of agreement between reviewers. During the spot checks, there was a good degree of concordance. There was disagreement between two reviewers on two papers, therefore a third reviewer in the team was consulted. The outcome in both cases was to exclude the papers. The most common reason for excluding studies from this review during the data extraction stage was because they were focused on describing dietary differences between populations without examining the factors driving dietary behaviour.

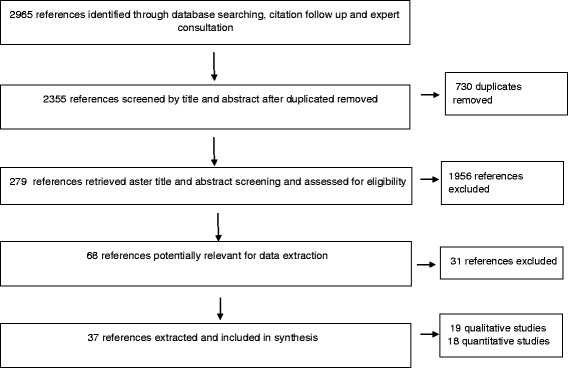

During the data extraction process 37 studies met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of systematic mapping search and selection process

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction was performed by the five reviewers according to the following study characteristics: study design, sampling population, sample characteristics, number of participants, country where the study was conducted, sampling method, dietary behaviour measured, factors reported to influence dietary behaviour. As the main aim of this mapping review was to gather a broad base of evidence to map the conceptual domain of factors potentially influencing dietary behaviours it was decided to include all factors reported by authors and not to restrict to those factors where a statistical relationship had been demonstrated. For quantitative studies, types of analysis were also extracted, whilst direct quotes were extracted from qualitative studies.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of quantitative and qualitative studies was undertaken using the standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers [20]. Each reviewer in the process of extracting data assessed the paper for quality as well. To ensure consistency in quality assessment, an independent reviewer (LM) cross-checked the quality assessment between the five reviewers. Additional files (Additional files 2 and Additional file 3) summarise the quality assessment scores given to the included studies.

Data analysis and emerging clusters

Two stages were used in the analysis. In the first stage, all factors influencing dietary behaviour identified in the selected papers were extracted and their association described with the different dietary behaviours observed.

The second stage involved sorting and structuring the factors into clusters, during which, the list of factors emerging from the review were clustered according to how they were seen to relate to each other, in a data driven approach [21]. This clustering step was part of a larger concept mapping process leading to the development of a systems-based framework of factors influencing dietary behaviour and physical activity/sedentary behaviour in ethnic minority groups living in Europe. The use of the concept mapping methodology [21] is explored in detail in a separate paper [14]. The concept mapping approach is guided by systems thinking, which can simply be defined as “looking at things in terms of the bigger picture” [22]. This concept mapping approach included steps on generating a list of factors, and sorting and structuring these factors into clusters by consensus based on how they relate to each other [19].

Within the DEDIPAC-KH, an inter-disciplinary group focused on the determinants of dietary and physical activity behaviours. This comprised a team specifically focussing on the factors influencing the behaviours of ethnic minority populations (‘DEDIPAC ethnic minority team’). Other parts of the DEDIPAC-KH focussed on the factors influencing dietary [23, 24] (Condello G, Ling FCM, Bianco A, Chastin S, Cardon G, Ciarapica D, et al. Using Concept Mapping in the Development of the EU-PAD Framework (European Physical Activity Determinants across the Life Course): a DEDIPAC-Study. Submitted) and physical activity behaviours of the general European population (‘DEDIPAC general population team’).

All 63 factors were grouped into seven clusters (Table 1) in two steps - firstly by a meeting of n = 5 members of the DEDIPAC ethnic minority team, followed by a confirmatory workshop of n = 21 members of DEDIPAC general population team. Experts representing a range of disciplines participated in the clustering process: nutrition, public health, epidemiology, anthropology, social demography, economics, sociology, dietetics, psychology, exercise physiology, health promotion and physical activity.

Table 1.

Dietary map of the 63 factors and the 7 clusters that emerged from the systematic mapping review

| Migration context | Social and cultural environment | Food beliefs and perceptions | Accessibility of food | The body | Psychosocial | Social and material resources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of factors | 7 | 16 | 11 | 10 | 5 | 9 | 5 |

| Factors | Region of origin Urban or rural dweller Age at migration Country of birth Length of stay in host country Place of residence in host country Westernization |

Cultural identity Ethnic identity Ethnicity Religious beliefs Equipping children in different social networks Perception of host culture Level of acculturation Religious prescriptions Socialization process in place of residence Conformity to tradition Traditional dietary values/beliefs Gender Age Social networks Social ties Social bonding |

Status of traditional vs convenience foods/diets Familiarization of host foods before migration Familiarization with host country foods Husband's food preferences Children's food preferences Inter-generational influences on diet Parental dietary habits Perception of healthy foods Food beliefs Perception of cost Social role of food |

Availability of traditional foods Accessibility of traditional foods Food prices Food-related life-style Neighbourhood level physical proximity Season Family’s neighbourhood (ethnic enclave) Lack of time for cooking traditional foods Time for food preparation Change in lifestyle (work/school commitments) |

Health consciousness Dieting Tendency BMI Body image perception and preferences for larger body size Child’s health |

Taste preferences Attitudes Subjective norms Perceived behaviour control Perceived behavioural intention Perceived group norms Past behaviour Motivation Food neophobia |

Competency in host language Educational attainment SES Income Nutrition knowledge |

Results

Description of included studies

The characteristics of the 37 included studies are presented in Tables 2 and 3 (19 qualitative; 18 quantitative). Most of the studies were conducted in Northern Europe, i.e.,(UK n = 9, Norway n = 9, The Netherlands n = 6 and Sweden n = 5). The most commonly studied ethnic minority groups were Pakistanis and Bangladeshis. Most of the studies were conducted among adults (n = 31), but studies on children/adolescents (n = 5) and on older adults (n = 1) were found. However, 11 of the studies conducted on adults included participants who were older adults and 3 other studies included children/adolescents. The number of participants ranged from 14 to 83 in the qualitative studies and 100–12,811 in the quantitative studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of quantitative studies on factors influencing dietary behaviour in minority groups

| Author | Country | Study population | Design | Participants | Dietary behaviour measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koochek et al., 2001 [27] | Sweden/Iran | Iranian-born residents of Stockholm/Iranians living in Iran | Cross- -sectional | Elderly ≥60 year Iranians in Sweden (N = 121; F = 66 %) Iranians in Teheran (N = 52; F = 40 %) |

Dietary intake including fruit and vegetables |

| Volken et al., 2013 [28] | Switzerland | Portuguese, German, Italian, Turkish, Serbian, Kosovan residents of Switzerland. | Cross-sectional | Participants aged 17–74 years. M = 5390, F = 6358 |

Fruit and vegetable intake |

| Edwards et al., 2010 [39] | UK | 36 nationalities of international students | Cross-sectional | Participant aged 20–60 year. N = 226 M = 31 %, F = 69 % |

Food neophobia, changes in eating habit |

| Ross et al., 2009 [59] | Sweden | Sami involved in reindeer herding (traditional lifestyle) vs others | Cross-sectional | N = 595 Sami (F = 321, M = 274) | Food and nutrient intake |

| Skreblin, et al., 2003 [29]. | Croatia | Three groups of adolescents: host; immigrant (Bosnia Herzegovina); permanently settled | Cross-sectional | N = 510 adolescents (14–19 years.) | Food intake, dieting practice |

| Brustad et al., 2007 [47] | Norway | SAMI and Norwegian who had childhood in SAMINOR study | Cross-sectional | Participant aged 36–79 years. N = 7614 both M & F |

Dietary patterns in childhood based on clustering of 11 ‘traditional’ Sami food items |

| Brustad et al., 2008 [60] | Norway | SAMI and Norwegian | Cross-sectional | Participant aged 36–79 years. N = 12811 Age: both M & F |

Dietary patterns based on traditional and modern dietary items. |

| Kumar et al., 2004 [26] | Norway | East Asians, Indians, sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East/North Africa- | Cross-sectional | Adolescents resident in Oslo. Mean age 15.6 years.; N = 1659 (M = 48.9 %,F = 51.1 %) |

Fruit and vegetable intake, breakfast skipping. |

| Kassam-Khamis et al., 2000 [9] | UK | South Asian Muslims from Bangladesh, Pakistan East Africa (Ismailis) | Cross-sectional | Households include everyone >12 years. N = 291 individuals in 92 households (n = 100 Bangladeshis; n = 108 Pakistanis; n = 83 Ismailis) |

Food intake |

| Harding et al., 2008 [61] | UK | Black Caribbean, Black African, Pakistani, Indian Bangladeshi | Cross-sectional | Children aged 11–13 years. pupils in 51 schools N = 6599 |

Food intake including fizzy drinks, fruit and vegetables, breakfast |

| Nicolaou et al., 2006 [10] | Netherlands | Surinamese of South Asian and African origin, white Dutch | Cross-sectional | Adults aged 35–60 year. N = 1518 |

“Diet Quality” based on the Intake of a number of key foods and breakfast |

| Nielsen et al., 2014 [50] | Denmark | Non Western minorities; Turkish (35 %) Pakistani/Indian background (20 %), “other” covers >100 different countries | Cross-sectional | Parents with children 6 months to 3.5 years. Danish and non-western N = 337 | Dietary intake, dietary pattern (healthy eating) |

| Carrus et al., 2009 [49] | Italy | Indian females | Cross-sectional | Females 18–34 years. living in Rome for ≥ 10 year N = 100 | Purchase of ethnic food |

| Perez-Cueto 2009 [40] | Belgium | International students from 60 nationalities | Cross-sectional | Students aged 19–48 years. N = 235; M = 54 % |

Perceived changes in dietary habits, healthy intake |

| Kjøllesdal et al., 2013 [62] | Norway | Pakistani women with type 2 diabetes | RCT | Participant aged 25–62 years. N = 198 |

Change in food intake |

| Kjollesdal et al., 2010 [63] | Norway | Pakistani women living in Norway and born in Pakistan or born in Norway by two Pakistani parents. | RCT | Women aged 28–62 years. N = 82 |

Healthy dietary intake |

| Khunti et al., 2008 [64] | UK | Schools with a >60 % South Asian population, mainly Indian origin. | Action research | Pupils aged 11–15 years, N = 4763, (77 % South Asian) | Dietary pattern (healthy and unhealthy intake) |

| Johansen et al., 2010 [65] | Norway | Women living in Norway and born in Pakistan or women born in Norway by two Pakistani parents. | RCT | Women aged 25–63 years. N = 198 |

Dietary intake, portion size, intention to change diet |

Table 3.

Characteristics of qualitative studies on factors influencing dietary behaviour in minority groups

| Author | Country | Study population | Design | Participants | Dietary behaviour measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawrence et al., 2007 [43] | UK | African (Somalia, Zimbabwe) South Asian (Pakistani/Bangladeshi) females | 6 Focus groups | Girls and young women aged 12–35 years N = 33 |

Food choice |

| Lawton et al., 2008 [36] | UK | Pakistanis, Indians with type 2 diabetes | In-depth interviews | Adults aged 33–71 year. M = 15, F = 17 N = 32 |

Food and eating practices, dietary change |

| Fargerli et al., 2005 [25] | Norway | Pakistani-born living in Oslo | In-depth interviews | Adults aged 38–66 years. M = 4, F = 11 N = 15 |

Changes in food -habits whilst living in Norway after diabetes diagnosis |

| Garnweidner et al., 2012 [41] | Norway | Female immigrants form 11 African and Asian countries residing in Oslo | In-depth interviews | Participants aged 25–60 year. N = 21 |

Food habits, meal preparation, perception of change in food habits |

| Halkier et al., 2011 [66] | Denmark | Pakistani living in Denmark | Interviews, participant observation |

N = 19 Age = 15–65 years. |

Healthy eating practices |

| Kohinor et al., 2011 [30] | Netherlands | Dutch Surinamese | Semi-structured interviews | N = 32 M = 12, F = 20 | Healthy dietary intake |

| Ahlqvist et al., 2000 [67] | Sweden | Iranian women living in Sweden | Interviews | Women aged 29–85 years. N = 14 |

Food intake |

| Grace et al., 2008 [38] | UK | Bangladeshi adults | 17 focus groups and 8 interviews | Bangladeshis without diabetes (M = 37; F = 43); religious leaders (M = 14, F = 15); health professionals (F = 19; M = 1) |

Dietary intake in relation to the prevention of type 2 diabetes |

| Terrangi et al., 2014 [42] | Norway | Somali, Pakistani,Sri Lanka, Iraq, Turkey, Iran, Egypt, Algeria, Lebanon, Morocco | semi-structured interviews | Women aged 25–70 year. N = 21 |

Shopping, preparation and eating habits, dietary acculturation |

| Jonsson et al., 2002 [31] | Sweden | Somalians | Focus group interviews | 19 women with children <18 years. | Food choice, tradition, meanings attached to ‘feeding the family’ |

| Hendriks et al., 2012 [32] | Netherlands | Surinamese Indians | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | Participants aged 29–83 years. F = 24. M = 3 N = 27 |

Eating habits |

| Rawlins et al., 2013 [37] | UK | African; Caribbean; Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi | Focus groups and interviews | Children aged 8–13 years. and their parents N = 43 parents, N = 70 children |

Perception of healthy eating and shopping practices |

| Tuomaimen 2009 [33] | UK | Ghanaians | Indepth-interview and participant observation | 18 households (N = 41 individuals), 24 key informants |

Meal format, eating pattern, meal cycle, shopping practices, food preferences |

| Nicolaou et al., 2009 [34] | Netherlands | Turkish/Moroccan | 14 Focus groups |

N = 83 aged = 20–40 year. |

Food intake |

| Nicolaou et al., 2013 [8] | Netherlands | South Asian Surinamese | Focus group discussions | N = 5 Adults (N = 4-6 per group); | Food intake, healthy eating |

| Nicolaou et al., 2012 [44] | Netherlands Morocco | Moroccan | 8 focus groups |

N = 53 aged = 16–59 years. |

Changes in and diet |

| Nielsen 2013 [48] | Denmark | Turkish and Pakistani mothers living in Denmark | Focus groups | Mothers aged = 25–35 years with at least one child < 30 months N = 20 |

Food choice, eating behaviour |

| Jonsson 2002 [35] | Sweden | Bosnian Muslim immigrants in Sweden. | Focus groups |

N = 20 Women with children <18 years. |

Food choice |

| Mellin-Olsen et al., 2005 [68] | Norway | Pakistani immigrants in Norway | Focus groups | N = 25 women, | Dietary change in meal pattern, meal preparation, intake of specific foods |

The 12 dietary behaviours (as stated by authors) examined in the included studies (Tables 2 and 3) were food intake, fruit and vegetable intake, changes in food habits, intention to change diet, product purchase, meal preparation, dietary acculturation, dietary intake (healthy/unhealthy intake), eating habits, food neophobia, dieting and diet quality. Dietary behaviour as used in this review encompasses all food related behaviours that are grouped into three main categories [23] 1. Food choice, consists of outcomes preceding the actual consumption (e.g., produce purchase and intentions); 2. Eating behaviour, comprising outcomes to do with the actual act of eating (e.g., dieting and food neophobia); and 3. Dietary intake consisting of all outcomes related to what is consumed (e.g., fruits and vegetable intake and healthy versus unhealthy.

Factors influencing dietary behaviours

There were some commonalities and differences in factors influencing dietary behaviour across different ethnic minority groups. For instance, lack of availability of traditional food, foods meeting religious prescriptions, and preferred foods were identified in all study populations irrespective of the region of origin or country of settlement. Religious beliefs and prescription was a common factor influencing dietary behaviour in all studies conducted among South Asians (Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Indians), African, Middle Eastern and Eastern European immigrants. Taste preference was another frequently reported factor, irrespective of the population or setting of the study. Factors reported by specific populations included fluency in the host language identified in a study conducted among diabetic Pakistani born persons living in Oslo [25] and traditional lifestyle as deduced from occupation, e.g., reindeer herder reported in both papers addressing diet among the Sami and non-Sami groups in Norway (41, 47). Also a number of studies found differential associations between socioeconomic status (SES) and dietary behaviour [9, 10, 26–29]. For instance, SES was not associated with dietary behaviour among populations from East Asia, Indians and African origin in Norway [26], or in a Surinamese population in the Netherlands [10], whilst in a study conducted in the UK, SES influenced dietary intake among South Asians from Bangladesh. All factors are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Emerging factors and their association with dietary behaviours across different populations

| Cluster | Factor | Dietary behaviour | Evidence | Study population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migration context | Region of origin | Eating behaviour | [33] | Ghanaians |

| Urban or rural dweller | Food neophobia | [39] | International students | |

| Fruit and vegetable intake | [28] | Portuguese, German, Italian, Turkish, Serbian, Kosovan residents of Switzerland | ||

| Country of birth | Food neophobia | [39] | International students | |

| Length of stay in host country | Food neophobia | [29, 39] | International students; Immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Place of residence in host country | Food intake | [29] | Immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Age at migration | Diet quality | [10] | Surinamese of South Asian and African origin | |

| Westernization | Changes in diet | [38] | Moroccans | |

| Social and cultural environment | Cultural identity | Food intake | [9, 34] | South Asian, East Africa (Ismailis), Somalian |

| Food choice | [31] | Turkish/Moroccan | ||

| Changes in diet | [44] | Moroccan | ||

| Healthy dietary intake | [30] | Dutch Surinamese | ||

| Eating habits | [32] | Surinamese Indians | ||

| Eating behaviour and food choice | [33] | Ghanaians | ||

| Religious beliefs | Food choice | [35] | Bosnian Muslim immigrants in Sweden | |

| Eating behaviour and dietary change | [36] | South Asians with type 2 diabetes | ||

| Perception of healthy eating and shopping practices | [37] | African Caribbean and South Asian | ||

| Dietary intake in relation to type 2 diabetes | [69] | South Asian | ||

| Perception of host culture | Eating behaviour, meal preparation, perception of change in food habits | [41] | African and Asian | |

| Level of acculturation | Food intake | [29, 34] | Turkish/Moroccan; Immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Religious prescriptions | Shopping, preparation and eating behaviour, dietary acculturation | [42] | Somali, Pakistani, Sri Lanka, Iraq, Turkey, Iran, Egypt, Algeria, Lebanon, Morocco | |

| Socialization process in place of residence | Food intake | [29] | Immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Conformity to tradition | Food choice | [31, 33] | Somalians, Ghanaians | |

| Traditional dietary values/beliefs | Perception of healthy eating and shopping practices | [37] | African Caribbean and South Asian | |

| Gender | Fruit and vegetable intake | [28] | Portuguese, German, Italian, Turkish, Serbian, Kosovan residents of Switzerland. | |

| Food neophobia | [39] | International students | ||

| Dietary intake | [47] | Sami | ||

| Social networks | Changes in diet | [68] | South Asian | |

| Social ties | Food intake | [34] | Turkish/Moroccan | |

| Age | Dietary intake | [27] | Iranian | |

| Fruit and vegetable intake | [28] | Portuguese, German, Italian, Turkish, Serbian, Kosovan residents of Switzerland | ||

| Social bonding | Eating behaviour and dietary change | [36] | South Asians with type 2 diabetes | |

| Taste preferences | Healthy dietary intake | [41, 66] | African and Asian; South Asian | |

| Food choice | [30] | Dutch Surinamese | ||

| Dietary intake (healthy/unhealthy intake) | [31] | Somalian | ||

| Food habits, meal preparation | [64] | South Asian | ||

| Food beliefs and perceptions | Status of traditional vs convenience foods/diets | Healthy dietary intake | [66] | South Asian |

| Familiarization of host foods before migration | Eating behaviour and food choice | [33] | Ghanaians | |

| Familiarization with host country foods | Food choice | [35] | Bosnian Muslim immigrants in Sweden | |

| Husband's food preferences | Changes in diet | [44] | Moroccan | |

| Children's food preferences | Changes in diet | [44, 68] | Moroccan; South Asian | |

| Inter-generational influences on diet | Food intake | [67] | Iranian | |

| Parental dietary habits | Food intake | [29] | Immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Perception of healthy foods | Healthy dietary intake | [40] | International students | |

| Food beliefs | Healthy dietary intake | [30] | Dutch Surinamese | |

| Food intake | [67] | Iranian | ||

| Perception of healthy eating and shopping practices | [37] | African Caribbean and South Asian | ||

| Perception of cost | Perception of healthy eating and shopping practices | [37] | African Caribbean and South Asian | |

| Dietary intake (healthy and unhealthy intake) | [64] | South Asian | ||

| Food choice | [43] | African, South Asian | ||

| Social role of food | Healthy dietary intake | [63] | South Asian | |

| Accessibility of food | Availability of traditional foods | Food intake; Food choice | [9, 43] | South Asian, East Africa (Ismailis); African south Asian |

| Food prices | Perception of healthy eating and shopping practices | [37] | African Caribbean and South Asian | |

| Food choice | [43] | African, South Asian | ||

| Neighbourhood level physical proximity | Perception of healthy eating and shopping practices | [37] | African Caribbean, South Asian | |

| Accessibility | Dietary intake | [38] | South Asian | |

| Changes in diet | [68] | South Asian | ||

| Season | Food intake | [9] | South Asian, East Africa (Ismailis) | |

| Changes in diet | [68] | South Asian | ||

| Food-related life-style | Shopping, preparation and eating habits, dietary acculturation | [42] | Somali, Pakistani, Sri Lanka, Iraq, Turkey, Iran, Egypt, Algeria, Lebanon, Morocco | |

| Lack of time for cooking traditional foods | Food habits, meal preparation | [41] | African and Asian | |

| Healthy dietary intake | [66] | South Asian | ||

| Time for food preparation | Dietary intake (healthy and unhealthy intake) | [64] | South Asian | |

| Food choice | [43] | African, South Asian | ||

| Change in lifestyle (work/school commitments) | Changes in diet | [44] | Moroccan | |

| Food choice | [31] | Somalian | ||

| Food intake | [34] | Turkish/Moroccan | ||

| Changes in diet | [44] | Moroccan | ||

| The body | Health consciousness | Food choice | [43] | African, south Asian |

| Changes in diet | [68] | South Asian | ||

| Dieting Tendency | Breakfast skipping | [26] | East Asians, Indians, sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East/North Africa | |

| Body image perception and preferences for larger body size | Dieting practice | [29] | Immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Child’s health | Food choice | [48] | Turkish and Pakistani mothers | |

| Psychosocial | Taste preferences | Dietary intake (healthy and unhealthy intake) | [64] | South Asian |

| Food habits, meal preparation | [41] | African and Asian | ||

| Healthy dietary intake | [66] [30] | South Asian, Dutch Surinamese | ||

| Food choice | [31] | Somalian | ||

| Attitudes | Purchase of ethnic food | [49] | South Asian | |

| Subjective norms | Purchase of ethnic food | [49] | South Asian | |

| Perceived behavioural intention | Purchase of ethnic food | [49] | South Asian | |

| Perceived group norms | Purchase of ethnic food | [49] | South Asian | |

| Past behaviour | Purchase of ethnic food | [49] | South Asian | |

| Motivation | Dietary intake (healthy and unhealthy intake) | [64] | South Asian | |

| Social and material resources | Competency in host language | Changes in diet; Dietary intake | [25, 38] | South Asian |

| Educational attainment | Dietary intake | [60] | Sami | |

| SES | Food intake | [9, 28, 29] | Immigrants from Bosnia Herzegovina; Portuguese, German, Italian, Turkish, Serbian, Kosovan residents of Switzerland; South Asian Muslims from Bangladesh, Pakistan East Africa (Ismailis) | |

| Income | Diet quality | [10] | Surinamese of South Asian and African origin | |

| Nutrition knowledge | Dietary intake | [38] | South Asian | |

| Changes in diet | [62] | South Asian |

Emerging clusters

Sixty-three individual factors resulted from the first step of the analysis and seven clusters emerged from the brainstorming and structuring process: social and cultural environment (16 factors), food beliefs and perceptions (11 factors), psychosocial (9 factors), accessibility of food (10 factors), social and material resources (5 factors), migration context (7 factors), and the body (5 factors). As shown in Table 1, the ‘social and cultural environment’ cluster contained the highest number of factors influencing dietary behaviours. These factors include cultural identity and desire to maintain traditional food identity [9, 30–34], religious beliefs and prescriptions [25, 35–38], social networks [10], social bonding [36], level of acculturation and socialization processes [10, 29, 34], social norms/social role of food [38] and gender [28, 39, 40]. Another set of factors was grouped under the cluster ‘accessibility of food’. This cluster includes factors relating to: availability of food in new environments and workplaces and included specific foods, such as traditional, ‘halal’, healthy or preferred foods [25, 35–38, 40–42], accessibility of food (e.g., physical access to traditional foods) [33, 37, 38, 43] and food price [37, 43]. Several factors were also grouped in the ‘food beliefs and perceptions’ cluster: beliefs regarding traditional foods and convenience foods [9, 31], family member preferences (husband/children) [31, 41, 44, 45], parental dietary habits [29], familiarisation of host foods before migration [33], familiarisation of food in new environments [35] and new ways of shopping [42], beliefs and perceptions of healthy food [30, 37, 43], and perception of cost [37]. The ‘migration context’ cluster consists of factors influencing dietary behaviour such as region of origin [33, 46] and country of origin [29, 47] length of stay [29, 39] and age [10]. The ‘body’ cluster includes factors such as health [35, 38, 48], dieting [26], BMI [27] and body size preferences [23]. The ‘psychosocial’ cluster included factors such perceived behavioural control, perceived grouped norms [49, 50], taste preference [41], motivation [50] and past behaviours [49]. This cluster of factors seems relevant to the South Asian population as shown in Table 4. The last set of factors was grouped under the ‘social and material resources’ cluster, which includes education [27], SES (index of income and education) [9, 10, 37, 49], competency in host language [25, 38], nutritional knowledge [35, 38], change in lifestyle (lifestyle referring to work/school commitments) and time for food preparation [37, 41].

Discussion

Europe has a growing population of ethnic minority groups whose dietary behaviours are potentially of public health concern and the factors driving these behaviours need to be understood. This review identified a broad range of factors and clusters influencing dietary behaviour and identified gaps in the literature to guide future research. The evidence from this review will feed into developing a framework for the study of factors influencing dietary behaviours in ethnic minority populations in Europe.

This review extracted 63 individual factors that were grouped in seven clusters. Two clusters, ‘social and cultural environment’ and ‘food beliefs and perceptions’ had the highest number of factors shown to shape dietary behaviours of ethnic minority populations. These findings corroborate those of earlier reviews on ethnic minority populations [11, 5], in the sense that like other reviews, most factors identified are related to the socio-cultural environment, cultural beliefs and perceptions around food. In our review, factors are clustered in a way that cut across the more traditionally used socio-ecological levels (individual, family, community and society, see for example [51, 52]). The socio-ecological model presents different layers of influence, with an underlying assumption that the layers operate in linearity. Thus community factors are presumed to influence the individual via the family, whereas certain community factors may directly influence dietary choices, bypassing the family. In addition, the socio-ecological model depicts reality as artificially separating individual and social experiences. Clustering factors into systems may provide a more adequate means of depicting interrelationships between the factors. For example, in our analysis, social norms and identity were clustered together but would have been classified as ‘community’ and ‘individual’ factors using the socio-ecological model. By analysing data in this way, we aimed to explore the underlying mechanisms that shape dietary behaviours, in a holistic, systems-based approach. This is in line with recent work that seeks to understand dietary choice as a social practice [53].

Our review identified some factors that have also been shown to influence dietary behaviours of majority populations. These include food price, income [54], social networks [54], time constraints and food availability [55], although these factors are often reported in low income groups [54]. However, many of the factors known to influence diet among majority populations were not identified in our review. For instance, a recent umbrella review among adults [56] of studies conducted in Europe, Australia and North America, identified political environments, food advertising, late-shift work, behavioural regulation and sedentary behaviour as important correlates of dietary behaviour but these factors were absent in our review. This might be due to a bias in studies amongst ethnic minority groups, as there is a tendency by researchers to focus on socio-cultural factors. Factors that were identified as unique to immigrant origin groups included all factors within the ‘migration context’ cluster, and some from other clusters, e.g.; level of acculturation, cultural identity, availability of traditional foods, familiarity with host country foods, competency in host language, perception of host culture and religious prescriptions. While the majority of studies explored ‘differences’ across ethnic groups, this review found a need for research exploring ‘similarities’. This would be useful in adapting mainstream interventions for ethnic minority groups.

It is important to note that although dietary behaviour is generally considered to be associated with SES [54], in our review SES was inconsistently related to dietary behaviour. For instance, a study conducted among adolescents in Oslo [26] reported that SES using a composite measure of parental occupation, mother’s education, employment status and social security status was not associated with diet quality across the study sample of South Asian and African adolescents. In contrast, in other studies [27–29], education was identified to be a determinant of selected food intakes, including fruit and vegetables among elderly Iranian-born residents of Stockholm. The inconsistencies in the relationship between SES and diet corroborates previous studies that have observed differences between SES and metabolic outcomes in different migrant populations [57]. It has been hypothesised that these groups might be in another stage of epidemiological transition, where diet-related NCDs (and risk factors) are still more prevalent (or equally so) in higher SES groups, as was the case among European populations in the 1950s and 60s.

Almost half the studies (44 %) included in this review were focused on South Asians, which is not surprising given that this group forms the largest ethnic minority group in some countries in northern Europe, where most of the studies were conducted [11]. The ‘psychosocial’ cluster of factors seems relevant only to the South Asian population in our review, however, this is a reflection of only one study, therefore, there is insufficient evidence to be able to conclude that these factors are only important to South Asian populations. The findings should be interpreted with caution as not all factors may be applicable to all ethnic minority groups, as they are heterogeneous populations in terms of their acculturation level, ethnicity, socio-demographic status and religion.

Factors that were included in the ‘social and cultural environment’ and ‘food beliefs and perceptions’ clusters appeared to influence dietary behaviours amongst almost all minority groups. Among studies conducted with South Asians (Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Indians) and other migrants from predominantly Muslim countries, religious beliefs and prescriptions were identified as important factors.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This is the first systematic mapping review that has mapped out factors influencing dietary behaviour among a diverse population of minority groups living in Europe. One difference between this review and others is in the method used in synthesizing the findings. Most reviews have used existing frameworks for this purpose [52, 58]. The approach used in this review has resulted in clustering of factors that transcends existing models, aiming to better capture the complexity of the system of factors influencing dietary behaviour. Another strength of this review was the inclusion of indigenous groups and Eastern Europe migrants to Western Europe in the search strategy, recognising that these groups are potentially disadvantaged and marginalized and may be more vulnerable to NCDs. However, only three studies were identified that reported factors influencing dietary behaviours among the Sami [47, 59, 60] and minority groups from the former Eastern Bloc European countries who commonly migrate to other parts of Europe [28]. We found no studies on Roma populations.

Although migration is a phenomenon that is found in all European countries, most studies were conducted in Northern Europe, and predominantly among populations of South Asian origin. Few studies were conducted among children and older adults. Findings need to be interpreted with caution as factors might differ across age groups. Many studies excluded in the reviewing process focused on describing dietary differences and did not present findings on the factors driving behaviour, which partly accounts for the limited number of relevant studies included in the review. The inclusion of mainly cross-sectional quantitative studies in this review reflects the types of studies available, which also means that we cannot establish causal relationships between the factors identified and dietary behaviours. Whilst there was no limitation for language during the search strategy, our review consists of articles published entirely in English. This could be due to the fact that other relevant articles may not have been indexed in the electronic databases used for this review.

Implications of the findings

Future research is needed to further deepen our understanding of the interrelationships between identified factors both within and between clusters. In addition, future studies need to make direct comparisons between minority and majority populations to understand differences and commonalities in factors underlying dietary behaviours and food choice. We also recommend studies into a broader range of more ‘mainstream’ factors (as with the majority population). There is also a need for more studies including longitudinal data of factors influencing dietary behaviours across the life course, particularly of young people and older adults among ethnic minority groups. Finally, a gap was identified for studies comparing the drivers of dietary behaviours across a wide range of ethnic minority groups living in different contexts in Europe (including central and southern Europe) and including groups that are under-represented in national surveys such as the Roma, asylum seekers and refugees, which are increasingly relevant groups in Europe.

Conclusions

This review identified a broad range of factors and clusters of factors potentially influencing dietary behaviour among ethnic minority populations. Gaps in the literature included a need for researchers to explore the underlying mechanisms that shape dietary behaviours, which can be gleaned from more holistic, systems-based studies exploring relationships between factors and clusters. The dominance of studies exploring ‘differences’ between ethnic minority groups and the majority population in terms of the socio-cultural environment and food beliefs suggests a need for research exploring ‘similarities’, that is the relative importance of factors influencing dietary behaviour in the general population in ethnic minority populations. This review shows that the range of factors that influence dietary behaviours among ethnic minority groups is broad. The evidence from this review will feed into the development of a framework for the study of factors driving influencing dietary behaviours in ethnic minority populations in Europe.

Abbreviations

BMI, body mass index; DEDIPAC-KH, DEterminants of DIet and Physical Activity Knowledge Hub; NCDs, non-communicable diseases; SES, socioeconomic status

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this paper was supported by the Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity Knowledge Hub (DEDIPAC-KH. This work is supported by the Joint Programming Initiative ‘Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life’. The funding agencies supporting this work are (in alphabetical order of participating Member State in this paper): Belgium: Research Foundation – Flanders; Norway: The Research Council of Norway; The Netherlands: The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw); The United Kingdom: The Medical Research Council (MRC). The authors will like to thank the information specialist, Maxine Johnson from the University of Sheffield and Faridi van Etten-Jamaludin, Medical library, AMC for their help in defining our search strategy and the entire DEDIPAC ethnic minorities team of the DEDIPAC project.

Availability of data and supporting materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contribution

All authors conceptualised and designed the study. HO, MN, KP, LT, MH screened and extracted the data. HO drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed draft versions of the manuscript and provided suggestions and critical feedback. All authors have made a significant contribution to this manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

HO is a PhD student of Public Health Nutrition, School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, UK. MN (PhD) is a Researcher at Academic Medical Centre, Department of Public Health, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. KP (PhD) is a Research Fellow and University Teacher in Public Health, School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, UK. LT (PhD) is an Associate Professor at Oslo and Akershus University College, Norway. LM (PhD) is a Professor at Ghent University. KS (PhD) is a Professor at the Academic Medical Centre, Department of Public Health, Amsterdam. NL (PhD) is a Professor at the Department of Nutrition, University of Oslo. MH (PhD, RD, RNutr) is a Professor of Public Health, School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, UK.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional files

Systematic search strategy in Medline. (DOCX 15 kb)

Contributor Information

Hibbah Araba Osei-Kwasi, Email: hasaeed1@sheffield.ac.uk.

Mary Nicolaou, Email: m.nicolaou@amc.uva.nl.

Katie Powell, Email: k.powell@sheffield.ac.uk.

Laura Terragni, Email: laura.terragni@hioa.no.

Lea Maes, Email: lea.maes@ugent.be.

Karien Stronks, Email: k.stronks@amc.uva.nl.

Nanna Lien, Email: nanna.lien@medisin.uio.no.

Michelle Holdsworth, Phone: (0044)114-222-0723, Email: michelle.holdsworth@sheffield.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Faskunger J, Eriksson U, Johansson S-E, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Risk of obesity in immigrants compared with Swedes in two deprived neighbourhoods. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):304. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel J, Vyas A, Cruickshank J, Prabhakaran D, Hughes E, Reddy K, et al. Impact of migration on coronary heart disease risk factors: comparison of Gujaratis in Britain and their contemporaries in villages of origin in India. Atherosclerosis. 2006;185(2):297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sjölander P. What is known about the health and living conditions of the indigenous people of northern Scandinavia, the Sami? Glob Health Action. 2011;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gatineau M, Mathrani S. Ethnicity and Obesity in the UK. Perspect Public Health. 2011;131(4):159–60. doi: 10.1177/1757913911412478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung G, Stanner S. Diets of minority ethnic groups in the UK: influence on chronic disease risk and implications for prevention. Nutr Bull. 2011;36(2):161–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-3010.2011.01889.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satia-Abouta J, Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Elder J. Dietary acculturation: applications to nutrition research and dietetics. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(8):1105–18. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earland J, Campbell J, Srivastava A. Dietary habits and health status of African-Caribbean adults. Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics. 2010;23(3):264–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2009.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicolaou M, Stronks K, van Dam R. Nutritional intake of Surinamese residents of Amsterdam South East: the role of acculturation. Ethn Health. 2004;9:S92–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassam-Khamis T, Judd PA, Thomas JE. Frequency of consumption and nutrient composition of composite dishes commonly consumed in the UK by South Asian Muslims originating from Bangladesh, Pakistan and East Africa (Ismailis) J Hum Nutr Diet. 2000;13(3):185–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277x.2000.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolaou M, van Dam RM, Stronks K. Acculturation and education level in relation to quality of the diet: a study of Surinamese South Asian and Afro-Caribbean residents of the Netherlands. Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics. 2006;19(5):383–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2006.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert PA, Khokhar S. Changing dietary habits of ethnic groups in Europe and implications for health. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(4):203–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darmon N, Khlat M. An overview of the health status of migrants in France, in relation to their dietary practices. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(2):163–72. doi: 10.1079/phn200064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Butland B, Jebb S, Kopelman P, McPherson K, Thomas S, Mardell J, Parry V. Tackling obesities: future choices-project report. Vol. 10. London: Department of Innovation, Universities and Skills; 2007.

- 14.Holdsworth M, Nicolaou M, Osei-Kwasi HA, Langøien LJ, Powell K, Terragni L, et al. Developing a framework map of the major determinants of dietary behaviour and physical activity/sedentary behaviour in minority ethnic groups living in Europe. Edinburgh: International Society for Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, International Society for Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity; 2015. p. 107. abstract book, S6.73. www.isbnpa2015.org.

- 15.Lakerveld J, Van Der Ploeg HP, Kroeze W, Ahrens W, Allais O, Andersen LF, et al. Towards the integration and development of a cross-European research network and infrastructure: the DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity (DEDIPAC) Knowledge Hub. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2009;26(2):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slater L. PubMed PubReMiner. Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association/Journal de l'Association des bibliothèques de la santé du Canada. 2014;33(2):106–7. doi: 10.5596/c2012-014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirsch ED, Kett JF, Trefil JS. The new dictionary of cultural literacy: What Every American Needs to Know. Bosston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2002.

- 19.Blais R, Maïga A. Do ethnic groups use health services like the majority of the population? A study from Quebec, Canada. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(9):1237–45. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. Edmonton: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR). HTA Initiative; 2004.

- 21.Trochim WM. An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann. 1989;12(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(89)90016-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Homer J, Hirsch G. Opportunities and demands in public health systems. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):452–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stok FM, Renner B, Hoffmann S, Volkert D, Boeing H, Ensenauer R, et al. The DONE framework: Creating, evaluating and updating of an interdisciplinary, dynamic framework 2.0 of determinants of nutrition and eating. 2016. (Manuscript under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Chastin SF, Buck C, Freiberger E, Murphy M, Brug J, Cardon G, et al. Systematic literature review of determinants of sedentary behaviour in older adults: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:127. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0292-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fagerli RA, Lien ME, Wandel M. Experience of dietary advice among Pakistani-born persons with type 2 diabetes in Oslo. Appetite. 2005;45(3):295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar BN, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Lien N, Wandel M. Ethnic differences in body mass index and associated factors of adolescents from minorities in Oslo, Norway: a cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(8):999–1008. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koochek A, Mirmiran P, Sundquist K, Hosseini F, Azizi T, Moeini AS, Johansson SE, Karlström B, Azizi F, Sundquist J. Dietary differences between elderly Iranians living in Sweden and Iran a crosssectional comparative study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Volken T, Ruesch P, Guggisberg J. Fruit and vegetable consumption among migrants in Switzerland. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(1):156–63. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012001292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Škreblin L, Sujoldžić A. Acculturation process and its effects on dietary habits, nutritional behavior and body-image in adolescents. Collegium Antropologicum. 2003;27(2):469-77. [PubMed]

- 30.Kohinor MJ, Stronks K, Nicolaou M, Haafkens JA. Considerations affecting dietary behaviour of immigrants with type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study among Surinamese in the Netherlands. Ethn Health. 2011;16(3):245–58. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.563557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonsson IM, Hallberg LRM, Gustafsson IB. Cultural foodways in Sweden: repeated focus group interviews with Somalian women. Int J Consum Stud. 2002;26(4):328–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1470-6431.2002.00247.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hendriks A-M, Gubbels J, Jansen M, Kremers S. Health Beliefs regarding Dietary Behavior and Physical Activity of Surinamese Immigrants of Indian Descent in The Netherlands: A Qualitative Study. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Tuomainen HM. Ethnic identity,(post) colonialism and foodways: Ghanaians in London. Food, Culture and Society: An International Journal of MultidisciplinaryResearch. 2009;12(4):525–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolaou M, Doak CM, van Dam RM, Brug J, Stronks K, Seidell JC. Cultural and social influences on food consumption in Dutch residents of Turkish and Moroccan origin: a qualitative study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(4):232–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jonsson IM, Wallin AM, Hallberg LR, Gustafsson IB. Choice of food and food traditions in pre-war Bosnia-Herzegovina: focus group interviews with immigrant women in Sweden. Ethn Health. 2002;7(3):149–61. doi: 10.1080/1355785022000041999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawton J, Ahmad N, Hanna L, Douglas M, Bains H, Hallowell N. ‘We should change ourselves, but we can't’: accounts of food and eating practices amongst British Pakistanis and Indians with type 2 diabetes. Ethn Health. 2008;13(4):305–19. doi: 10.1080/13557850701882910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rawlins E, Baker G, Maynard M, Harding S. Perceptions of healthy eating and physical activity in an ethnically diverse sample of young children and their parents: the DEAL prevention of obesity study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26(2):132–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grace C, Begum R, Subhani S, Kopelman P, Greenhalgh T. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in British Bangladeshis: qualitative study of community, religious, and professional perspectives. Br Med J. 2008;337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Edwards JSA, Hartwell HL, Brown L. Changes in food neophobia and dietary habits of international students. Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics. 2010;23(3):301–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez-Cueto F, Verbeke W, Lachat C, Remaut-De Winter AM. Changes in dietary habits following temporal migration. The case of international students in Belgium. Appetite. 2009;52(1):83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garnweidner LM, Terragni L, Pettersen KS, Mosdøl A. Perceptions of the host country’s food culture among female immigrants from Africa and Asia: Aspects relevant for cultural sensitivity in nutrition communication. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(4):335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terragni L, Garnweidner LM, Pettersen KS, Mosdøl A. Migration as a Turning Point in Food Habits: The Early Phase of Dietary Acculturation among Women from South Asian, African, and Middle Eastern Countries Living in Norway. Ecol Food Nutr. 2014;53(3):273–91. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2013.817402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawrence JM, Devlin E, Macaskill S, Kelly M, Chinouya M, Raats MM, et al. Factors that affect the food choices made by girls and young women, from minority ethnic groups, living in the UK. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2007;20(4):311–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicolaou M, Benjelloun S, Stronks K, van Dam R, Seidell J, Doak C. Influences on body weight of female Moroccan migrants in the Netherlands: a qualitative study. Health Place. 2012;18(4):883–91. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helland-Kigen KM, Råberg Kjøllesdal MK, Hjellset VT, Bjørge B, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Maintenance of changes in food intake and motivation for healthy eating among Norwegian-Pakistani women participating in a culturally adapted intervention. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(01):113–22. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar BN, Meyer HE, Wandel M, Dalen I, Holmboe-Ottesen G. Ethnic differences in obesity among immigrants from developing countries, in Oslo, Norway. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;30(4):684–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brustad M, Parr C, Melhus M, Lund E. Childhood diet in relation to Sami and Norwegian ethnicity in northern and mid-Norway–the SAMINOR study. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(02):168–75. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nielsen A, Krasnik A, Holm L. Ethnicity and children's diets: the practices and perceptions of mothers in two minority ethnic groups in Denmark. Maternal & child nutrition. 2015;11(4):948-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Carrus G, Nenci AM, Caddeo P. The role of ethnic identity and perceived ethnic norms in the purchase of ethnical food products. Appetite. 2009;52(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen A, Krasnik A, Vassard D, Holm L. Opportunities for healthier child feeding. Does ethnic position matter?–Self-reported evaluation of family diet and impediments to change among parents with majority and minority status in Denmark. Appetite. 2014;78:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. What can be done about inequalities in health? Lancet. 1991;338(8774):1059–63. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91911-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson T. Applying the socio-ecological model to improving fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African Americans. J Community Health. 2008;33(6):395–406. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blue S, Shove E, Carmona C, Kelly MP. Theories of practice and public health: understanding (un) healthy practices. Crit Pub Health. 2016;26(1):36-50.

- 54.Roberts K, Cavill N, Hancock C, Rutter H. Social and economic inequalities in diet and physical activity. London: Public Health England; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pollard J, Kirk S, Cade J. Factors affecting food choice in relation to fruit and vegetable intake: a review. Nutr Res Rev. 2002;15(02):373–87. doi: 10.1079/NRR200244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sleddens EF, Kroeze W, Kohl LF, Bolten LM, Velema E, Kaspers P, et al. Correlates of dietary behavior in adults: an umbrella review. Nutr Rev. 2015;73(8):477–99. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agyemang C, van Valkengoed I, Hosper K, Nicolaou M, van den Born B-J, Stronks K. Educational inequalities in metabolic syndrome vary by ethnic group: evidence from the SUNSET study. Int J Cardiol. 2010;141(3):266–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mehtälä MA, Sääkslahti AK, Inkinen ME, Poskiparta ME. A socio-ecological approach to physical activity interventions in childcare: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2014;11(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Ross AB, Johansson A, Vavruch-Nilsson V, Hassler S, Sjölander P, Edin-Liljegren A, et al. Adherence to a traditional lifestyle affects food and nutrient intake among modern Swedish Sami. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009;68(4):372–85. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i4.17371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brustad M, Parr CL, Melhus M, Lund E. Dietary patterns in the population living in the Sami core areas of Norway--the SAMINOR study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(1):82–96. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v67i1.18240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harding S, Teyhan A, Maynard MJ, Cruickshank JK. Ethnic differences in diet, physical activity and obesity. Manchester. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(1):162–72. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Råberg KM, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Does the "stages of change" construct predict cross-sectional and temporal variations in dietary behavior and selected indicators of diabetes risk among Norwegian-Pakistani women? J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;15:85–92. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9580-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kjøllesdal MK, Hjellset VT, Bjørge B, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Barriers to healthy eating among Norwegian-Pakistani women participating in a culturally adapted intervention. Scand J Pub Health. 2010;38(5 suppl):52-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Khunti K, Stone MA, Bankart J, Sinfield P, Pancholi A, Walker S, et al. Primary prevention of type-2 diabetes and heart disease: action research in secondary schools serving an ethnically diverse UK population. J Public Health. 2008;30(1):30–7. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johansen KS, Bjorge B, Hjellset VT, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Raberg M, Wandel M. Changes in food habits and motivation for healthy eating among Pakistani women living in Norway: results from the InnvaDiab-DEPLAN study. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(6):858–67. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009992047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Halkier B, Jensen I. Doing ‘healthier’food in everyday life? A qualitative study of how Pakistani Danes handle nutritional communication. Critical Public Health. 2011;21(4):471–83. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2011.594873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ahlqvist M, Wirfalt E. Beliefs concerning dietary practices during pregnancy and lactation. A qualitative study among Iranian women residing in Sweden. Scand J Caring Sci. 2000;14(2):105–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mellin-Olsen T, Wandel M. Changes in food habits among Pakistani immigrant women in Oslo, Norway. Ethnicity and Health. 2005;10(4):311-39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Grace C. Nutrition-related health management in a Bangladeshi community. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011;70(01):129–34. doi: 10.1017/S0029665110004003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]