Abstract

Purpose: Urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder and upper tract is prevalent. By subjecting a documented transcriptome data set of urothelial carcinoma of bladder (GSE31684) to data mining and focusing on genes linked to peptidase activity (GO:0008233), we recognized C1S as the most significantly upregulated gene related to an advanced tumor status and metastasis. We subsequently analyzed the association of both C1S mRNA and its encoded protein expression with the clinical and pathological significance.

Materials and Methods: We used real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction to detect C1S transcription levels in 20 cases each of urothelial carcinoma of bladder and upper tract. An immunohistochemical stain was conducted to determine C1s protein expression levels in patients with urothelial carcinoma of upper tract (n = 340) and urinary bladder (n = 295). Furthermore, we examined the correlation of C1s expression with clinicopathological characteristics, disease-specific survival, and metastasis-free survival.

Results: C1S transcription levels were significantly high in patients with advanced-stage tumors of both groups (all P < .05). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that C1s expression levels were significantly associated with adverse clinicopathological parameters in both groups of urothelial carcinoma (all P < .05). C1s overexpression predicted poor disease-specific and metastasis-free survival rates for both urothelial carcinoma groups in the univariate analysis, and it was also an independent prognostic factor in the multivariate analysis (all P < .05).

Conclusions: C1s may play a pivotal role in urothelial carcinoma progress and can represent a vital prognostic marker and a promising new therapeutic target in urothelial carcinoma.

Keywords: C1S gene, Complement component 1s, Urothelial carcinoma, Prognosis.

Introduction

Urothelial carcinomas (UCs) originate from the urothelial cells, the epithelial lining of the entire urinary tract from the upper urinary tract (UT) to urinary bladder (UB). The former consists of the renal pelvis and ureter. UC is the predominant histopathological type of UT malignancy, constituting >90% cases of UT cancer in developed countries.1 UC of the UB (UCUB) is a relatively common cancer in developed countries. For instance, it is the seventh most prevailing malignancy in the United States.2 In contrast to the relatively high prevalence of UCUB, UC of the UT (UCUT) is uncommon and forms only five to ten percent of all victims of UC.3 Nevertheless, the prevalence of UCUT is exceptionally high in Taiwan, particularly in southern Taiwan and blackfoot-disease-endemic areas.4,5 Etiologically, both UCUB and UCUT are caused by similar carcinogenic factors (e.g., tobacco smoking and occupational hazard of aromatic amines).6-8 However, certain diseases predispose patients to UCUT rather than to UCUB, such as Chinese herb nephropathy,9 Balkan nephropathy,9 and analgesic nephropathy.10 Nonetheless, the gene expression profiling of both UCUTs and UCUBs revealed similar results.11 In addition, the survival rates of patients in both groups were similar, considering the tumor stage and grade.12 These findings indicate that both UCUT and UCUB share a molecular pathway.

The immune system is a double-edged sword to cancer. It can recognize and kill nascent tumor cells through a complex mechanism called cancer immunosurveillance.13 By contrast, chronic inflammation induced by variable etiologies contributes to tumorigenesis in certain cancers.14 The complement system is an essential pathway in immunology and is implicated in cancer development, progression and susceptibility;15-17 the components of the complement system exhibit peptidase activity.18 Recently, various peptidases have been investigated in different cancers, thus revealing their prognostic value.19,20 However, neither genes associated with peptidase activity nor the complement system are comprehensively and systemically evaluated in UC. Therefore, we conducted data mining on a documented transcript expression profile (GSE31684) obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD, USA) repository and focused on peptidase activity (GO:0008233). We found that the transcription level of the complement component 1, s subcomponent (C1S) was most momentously upregulated, which was positively associated with both tumor invasiveness and metastases. This finding indicates that the C1S gene may take an important part in oncogenesis and tumor progression of UC. In the following research, we found C1S transcriptional levels were significantly higher in more advanced tumors. In addition, we firstly demonstrated that C1s protein overexpression was not only significantly associated with adverse clinicopathological features, but also a novel prognostic factor indicating poor outcome in both UCUTs and UCUBs.

Materials and Methods

Data Mining of GSE31684 to Identify the Most Significantly Altered Genes

The transcriptome data set GSE31684 used for data mining was obtained from the GEO repository of NCBI. A GeneChip® Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for analyzing the data set (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE31684) involving radical cystectomy specimens from 93 patients with UCUB. We used Nexus Expression 3 statistical software (BioDiscovery, El Segundo, CA, USA) to analyze all probe sets without filtering or preselection. Furthermore, under supervision, we analyzed the statistical significance of each differently expressed transcript by comparing the primary tumor status (high stage to low stage) and the presence or absence of metastatic events. We performed functional profiling by using transcriptomes of high-stage UCUBs (primary tumor [pT]2-pT4) with metastatic disease and of low-stage UCUBs (pTa and pT1) without metastatic tumor, aiming attention at those associated with peptidase activity (GO:0008233).

Patient and Tumor Specimen Selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Chi Mei Medical Center, Tainan, Taiwan (IRB10302015) and E-Da Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan (EMRP-104-123). We enrolled 635 consecutive surgically treated patients diagnosed with UC with curative intent between 1996 and 2004 from the archives of the Department of Pathology. Among the patients, 295 and 340 had UCUB and UCUT, respectively. Other histopathological entities as well as UC variants were excluded from this study. Patients with synchronous UCUT and UCUB were also excluded. Detailed treatment protocol was the same as our previous work.21

Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) for Assessing the Transcription Levels of C1S in UCUBs and UCUTs

For quantifying the transcription level of C1S, we extracted total RNAs from a recently diagnosed, separate cohort of 20 patients with UCUTs and 20 with UCUBs; we quantified the extracted RNAs and subjected them to a real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Both groups comprised 10 low-stage (pTa-pT1) and 10 high-stage (pT2-pT4) tumors. By using predesigned TaqMan assay reagents (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), we assessed the mRNA abundance of C1S (Hs01043795_m1) through the ABI StepOnePlus™ system (Applied Biosystems). We calculated the fold change of C1S gene expression of UC tumors relative to the normal counterparts as previously described.21

Immunohistochemical Study and Evaluation of C1s Expression

Tumor slides were prepared as previously described.21 After that, the slides were subsequently proceeded to incubation with primary antibody against C1s (Rabbit monoclonal, clone: EPR9066 (B), Cat No. ab134943, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) for 1 hour. We scored C1s protein expression levels by combining the intensity and percentage of immunostaining in the cytoplasm of UC cells to create an H score. The equation for evaluating the H score is as follows: H score = ΣPi(i + 1), where Pi represents the percentage of stained tumor cells for each percentage varying from 0% to 100%, and i means the intensity of immunoreactivity (0-3+). This formula yields a score ranging from 100 to 400, where 100 signifies that 100% of the cancer cells are unreactive and 400 signifies that 100% of the cancer cells are strongly immunoreactive (3+).

Statistical Analyses

We used SPSS V.14.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for statistical analysis. The C1s immunoreactivity median H score was applied as the cutoff point to bisect the two groups, UCUTs and UCUBs, into two subgroups, high- and low-C1s expression, respectively. We applied Pearson's χ2 test to compare the association between C1s expression and miscellaneous important clinicopathological parameters. The end-points analyzed included disease-specific (DSS) and metastasis-free survival (MeFS) as described in our previous work.21 Kaplan-Meier plots with log-rank test were used for univariate analyses, in which parameters demonstrating P < .1 were included in multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression. For the above-mentioned tests, two-tailed testing was conducted, and P < .05 was considered to be significant.

Results

C1S Gene was the Most Significantly Upregulated Gene Associated with Tumor Progression in UCUB Transcriptomes

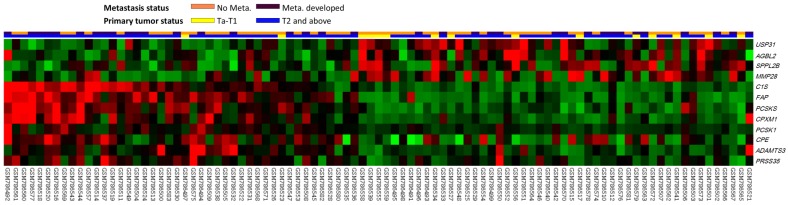

The analyzed transcriptome data set involved specimens from 93 patients with UCUBs; among these patients, 78 exhibited deeply invasive tumors (pT2-pT4) and 15 exhibited non-invasive or superficially invasive (pTa-pT1), of which 28 demonstrated metastases and 49 did not. Through transcriptome profiling, we identified 12 probes covering 12 transcripts associated with peptidase activity (GO:0008233). Fig. 1 shows that tumors with downregulated USP31, AGBL2, SPPL2B, and MMP28 as well as upregulated C1S, FAP, PCSKS, CPXM1, PCSK1, CPE, ADAMTS3, and PRSS35 tended to have a more advanced pT status and more frequent metastatic events compared with other tumors. As shown in Table 1, after the statistical analysis, the C1S transcript was the most significantly upregulated gene, with 1.4602- and 0.9181-fold log2 ratios compared with those of genes in both deeply invasive (pT2-pT4) and non-invasive to superficially invasive (pTa-pT1) tumors with or without metastases, respectively (both P < .005). No study has examined C1S in UC; therefore, we comprehensively investigated both C1S transcriptional and protein expression levels and their clinical significance in UC.

Figure 1.

Analysis of gene expression in urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder by using a published transcriptome data set (GSE31684). Conducting a clustering analysis of genes by focusing on peptidase activity (GO:0008233) revealed that C1S was one of the most significantly upregulated genes associated with a more advanced pT status and metastatic disease. Tissue specimens from cancers with distinct pT statuses are illustrated at the top of the heat map, and the expression levels of upregulated and downregulated genes are represented as a continuum of brightness of red or green, respectively. Specimens with unaltered mRNA expression are in black.

Table 1.

Summary of differentially expressed genes associated with peptidase activity (GO:0008233) and showed positive associations to cancer invasiveness and metastasis in the transcriptome of urothelial carcinoma of urinary bladder (GSE31684).

| 6.5 | Comparing T2-4 to Ta-T1 | Comparing Meta. to Non-Meta.# | Gene Symbol | Gene Title | Molecular Function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log ratio | p-value | log ratio | p-value | ||||

| 1555229_a_at | 1.4602 | 0.0001 | 0.9181 | 0.0013 | C1S | complement component 1; s subcomponent | calcium ion binding, complement component C1s activity, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, peptidase activity, rhodopsin-like receptor activity, serine-type endopeptidase activity, serine-type endopeptidase inhibitor activity, serine-type peptidase activity |

| 201117_s_at | 1.081 | 0.0048 | 0.8652 | 0.0037 | CPE | carboxypeptidase E | carboxypeptidase A activity, carboxypeptidase E activity, carboxypeptidase activity, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, metallopeptidase activity, peptidase activity, zinc ion binding |

| 205825_at | 0.3938 | 0.0087 | 0.3003 | 0.0088 | PCSK1 | proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 | calcium ion binding, hydrolase activity, peptidase activity, proprotein convertase 1 activity, serine-type endopeptidase activity, subtilase activity |

| 209955_s_at | 1.5836 | <0.0001 | 0.5783 | 0.0051 | FAP | fibroblast activation protein; alpha | dipeptidyl-peptidase IV activity, hydrolase activity, metalloendopeptidase activity, peptidase activity, prolyl oligopeptidase activity, protein dimerization activity, protein homodimerization activity, serine-type endopeptidase activity, serine-type peptidase activity |

| 213652_at | 0.5635 | <0.0001 | 0.3841 | 0.0002 | PCSK5 | proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 5 | hydrolase activity, peptidase activity, serine-type endopeptidase activity, subtilase activity |

| 214913_at | 0.2909 | 0.0009 | 0.2036 | 0.0025 | ADAMTS3 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif; 3 | heparin binding, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, metalloendopeptidase activity, metallopeptidase activity, peptidase activity, zinc ion binding |

| 227860_at | 0.6945 | <0.0001 | 0.4549 | 0.0001 | CPXM1 | carboxypeptidase X (M14 family); member 1 | carboxypeptidase A activity, carboxypeptidase E activity, carboxypeptidase activity, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, metallopeptidase activity, peptidase activity, zinc ion binding |

| 235874_at | 0.3376 | 0.0001 | 0.2276 | 0.0007 | PRSS35 | protease; serine; 35 | peptidase activity, serine-type endopeptidase activity |

| 1558117_s_at | -0.5337 | 0.0039 | -0.4279 | 0.0026 | USP31 | ubiquitin specific peptidase 31 | cysteine-type peptidase activity, hydrolase activity, peptidase activity, ubiquitin thiolesterase activity |

| 210693_at | -0.376 | <0.0001 | -0.1507 | 0.001 | SPPL2B | signal peptide peptidase-like 2B | aspartic-type endopeptidase activity, hydrolase activity, peptidase activity |

| 220390_at | -0.1759 | 0.0032 | -0.1536 | 0.0007 | AGBL2 | ATP/GTP binding protein-like 2 | carboxypeptidase A activity, carboxypeptidase activity, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, metallopeptidase activity, peptidase activity, zinc ion binding |

| 239272_at | -1.4769 | <0.0001 | -0.7875 | 0.0022 | MMP28 | matrix metallopeptidase 28 | calcium ion binding, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, metalloendopeptidase activity, metallopeptidase activity, peptidase activity, zinc ion binding |

#, Meta., distal metastasis developed during follow-up; Non-Meta.: no metastatic event developed.

C1S Transcripts were More Abundant in More Advanced Tumors of Both UCUT and UCUB Groups

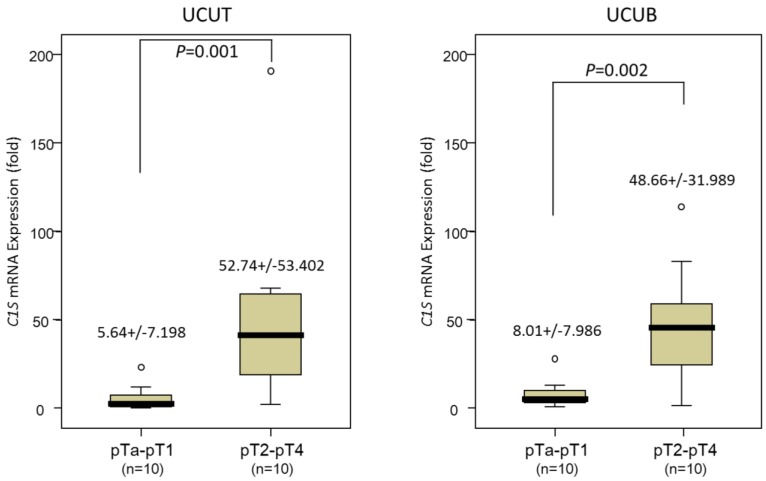

Real-time RT-PCR revealed that the C1S transcripts were significantly more abundant in tumors of a higher pT status (pT2-pT4) than in those of a lower pT status (pTa-pT1) in the 20 patients with UCUTs and 20 with UCUBs (P = .001 and .002 for UCUT and UCUB, respectively; Fig. 2), suggesting that C1S takes an influential part in UC advancement.

Figure 2.

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis. This analysis revealed a significantly higher C1S transcription level in both urothelial carcinomas of the upper urinary tract (left panel) and urinary bladder (right panel), with a more advanced primary tumor aggressiveness, compared with non-invasive and superficially invasive tumors (pTa-pT1) and deeply invasive ones (pT2-pT4), respectively (all P < .005).

Clinical and pathological Characteristics of UCUTs and UCUBs

Table 2 presents a summary of the clinical and pathological features of both UCUT and UCUB groups. No sex predominance was observed in the UCUT group (M:F = 158:182, 46.5%:53.5%); however, male predominance was observed in the UCUB group (n = 216, 73.2%). Moreover, 159 (46.8%) patients with UCUT and 123 (41.7%) with UCUB had high-stage (pT2-pT4) tumors, whereas 181 (53.2%) patients with UCUTs and 172 (58.3%) with UCUBs had low-stage (pTa-pT1) tumors; 28 (8.2%) patients with UCUTs and 29 (9.8%) with UCUBs had nodal metastases at diagnosis. In both groups, most tumors were of a high histopathological grade (83.5% for UCUT and 81.0% for UCUB, respectively). Vascular invasion and perineural invasion were observed in 106 (31.1%) and 19 (5.6%) patients with UCUT as well as in 49 (16.6%) and 20 (6.8%) patients with UCUB, respectively. Furthermore, 167 (49.1%) patients with UCUT and 156 (52.9%) with UCUB revealed high mitotic activity (10 or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields). In the UCUT group, synchronous multifocal tumors occurred in 62 (18.2%) patients; of these, both renal pelvis and ureter were involved in 49 (14.4%) patients.

Table 2.

Correlations between C1s expression and other important clinicopathological parameters in urothelial carcinomas.

| Parameter | Category | Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma | Urinary Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | C1s Expression | p-value | Case No. | C1s Expression | p-value | ||||

| Low | High | Low | High | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 158 | 74 | 84 | 0.277 | 216 | 112 | 104 | 0.251 |

| Female | 182 | 96 | 86 | 79 | 35 | 44 | |||

| Age (years) | < 65 | 138 | 67 | 71 | 0.659 | 121 | 58 | 63 | 0.587 |

| ≥ 65 | 202 | 103 | 99 | 174 | 89 | 85 | |||

| Tumor location | Renal pelvis | 141 | 64 | 77 | 0.228 | - | - | - | - |

| Ureter | 150 | 77 | 73 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Renal pelvis & ureter | 49 | 29 | 20 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Multifocality | Single | 278 | 135 | 143 | 0.261 | - | - | - | - |

| Multifocal | 62 | 35 | 27 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Primary tumor (T) | Ta | 89 | 64 | 25 | <0.001* | 84 | 70 | 14 | <0.001* |

| T1 | 92 | 67 | 25 | 88 | 50 | 38 | |||

| T2-T4 | 159 | 39 | 120 | 123 | 27 | 96 | |||

| Nodal metastasis | Negative (N0) | 312 | 163 | 149 | 0.006* | 266 | 142 | 124 | <0.001* |

| Positive (N1-N3) | 28 | 7 | 21 | 29 | 5 | 24 | |||

| Histological grade | Low grade | 56 | 40 | 16 | <0.001* | 56 | 45 | 11 | <0.001* |

| High grade | 284 | 130 | 154 | 239 | 102 | 137 | |||

| Vascular invasion | Absent | 234 | 147 | 87 | <0.001* | 246 | 136 | 110 | <0.001* |

| Present | 106 | 23 | 83 | 49 | 11 | 38 | |||

| Perineural invasion | Absent | 321 | 165 | 156 | 0.034* | 275 | 142 | 133 | 0.021* |

| Present | 19 | 5 | 14 | 20 | 5 | 15 | |||

| Mitotic rate (per 10 high power fields) | < 10 | 173 | 96 | 77 | 0.039* | 139 | 82 | 57 | 0.003* |

| >= 10 | 167 | 74 | 93 | 156 | 65 | 91 | |||

* Statistically significant.

C1s Immunostaining and Clinicopathological Correlations in UCUTs and UCUBs

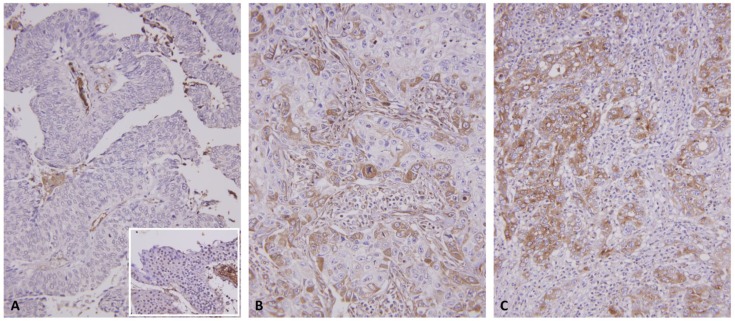

According to the C1s expression levels, both study groups were divided into two subgroups, namely high and low C1s expression, and their association with diverse clinicopathological parameters was analyzed through a chi-squared test (Table 2). A high C1s expression level in both UCUTs and UCUBs was significantly associated with a stepwise advancement of primary tumor status from pTa and pT1 to pT2-pT4 (both P < .001, Fig. 3), metastatic tumors to lymph nodes (P = .006 for UCUT and P < .001 for UCUB), a high histopathological grade (both P < .001), vascular invasion (both P < .001), perineural invasion (P = .034 for UCUT; P = .021 for UCUB), and a high mitotic activity (P = .039 for UCUT; P = .003 for UCUB).

Figure 3.

C1s immunostain on representative sections revealed a stepwise increment in C1s immunoreactivity from the nontumoral urothelial epithelium (inlet) and non-invasive papillary urothelial carcinomas (A) to non-muscle invasive (pT1) (B), and muscle invasive (pT2-pT4) urothelial carcinomas (C).

Survival Analyses for the UCUT Group

Table 3 shows the results of the survival analyses for the UCUT group. In the univariate analysis, multifocality, a stepwise advancement of the pT status, nodal metastasis, a high histopathological grade, vascular and perineural invasion were significantly associated with both shorter DSS and MeFS for UCUT tumors (all P < .05). The tumor location was associated with deteriorated DSS rates, but not MeFS rates, in patients with UCUT (P = .0079). In the multivariate analysis, multifocal tumors, nodal metastasis, a high histological grade, and perineural invasion independently predicted both adverse DSS and MeFS rates in patients with UCUT (all P < .05). An advanced pT status was independent prognosticator for the DSS only (P = .015); and vascular invasion was independent one for MeFs only (P = .003).

Table 3.

Univariate log-rank and multivariate analyses for Disease-specific and Metastasis-free Survivals in upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma.

| Parameter | Category | Case No. | Disease-specific Survival | Metastasis-free Survival | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

| No. of event | p-value | R.R. | 95% C.I. | p-value | No. of event | p-value | R.R. | 95% C.I. | p-value | |||

| Gender | Male | 158 | 28 | 0.8286 | - | - | - | 32 | 0.7904 | - | - | - |

| Female | 182 | 33 | - | - | - | 38 | - | - | - | |||

| Age (years) | < 65 | 138 | 26 | 0.9943 | - | - | - | 30 | 0.8470 | - | - | - |

| ≥ 65 | 202 | 35 | - | - | - | 40 | - | - | - | |||

| Tumor side | Right | 177 | 34 | 0.7366 | - | - | - | 38 | 0.3074 | - | - | - |

| Left | 154 | 26 | - | - | - | 32 | - | - | - | |||

| Bilateral | 9 | 1 | - | - | - | 0 | - | - | - | |||

| Tumor location | Renal pelvis | 141 | 24 | 0.0079* | 1 | - | 0.997 | 31 | 0.0659 | - | - | - |

| Ureter | 150 | 22 | 0.859 | 0.462-1.598 | 25 | - | - | - | ||||

| Renal pelvis & ureter | 49 | 15 | 1.334 | 0.370-4.805 | 14 | - | - | - | ||||

| Multifocality | Single | 273 | 48 | 0.0026* | 1 | - | 0.005* | 52 | 0.0127* | 1 | - | <0.001* |

| Multifocal | 62 | 18 | 3.026 | 1.400-6.540 | 18 | 2.517 | 1.453-4.360 | |||||

| Primary tumor (T) | Ta | 89 | 2 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.015* | 4 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.180 |

| T1 | 92 | 9 | 5.281 | 0.834-33.444 | 15 | 2.807 | 0.865-9.110 | |||||

| T2-T4 | 159 | 50 | 7.405 | 1.286-42.636 | 51 | 2.657 | 0.823-8.582 | |||||

| Nodal metastasis | Negative (N0) | 312 | 42 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | <0.001* | 55 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | <0.001* |

| Positive (N1-N3) | 28 | 19 | 5.707 | 3.085-10.558 | 15 | 3.135 | 1.698-5.788 | |||||

| Histological grade | Low grade | 56 | 4 | 0.0215* | 1 | - | 0.029* | 3 | 0.0027* | 1 | - | 0.020* |

| High grade | 284 | 57 | 3.507 | 1.137-10.814 | 67 | 4.259 | 1.251-14.496 | |||||

| Vascular invasion | Absent | 234 | 24 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.160 | 26 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.003* |

| Present | 106 | 37 | 1.531 | 0.845-2.774 | 44 | 2.459 | 1.347-4.487 | |||||

| Perineural invasion | Absent | 321 | 50 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | <0.001* | 61 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.009* |

| Present | 19 | 11 | 4.045 | 1.931-8.476 | 9 | 2.712 | 1.289-5.708 | |||||

| Mitotic rate (per 10 high power fields) | < 10 | 173 | 27 | 0.167 | - | - | 30 | 0.0823 | - | - | ||

| >= 10 | 167 | 34 | - | - | 40 | - | - | |||||

| C1s expression | Low | 170 | 8 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | <0.001* | 18 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.006* |

| High | 170 | 53 | 1.755 | 1.385-2.225 | 52 | 1.482 | 1.117-1.967 | |||||

* Statistically significant

Survival Analyses for the UCUB Group

Table 4 presents the results of the survival analyses for UCUBs. In the univariate analysis, a stepwise advancement of the primary tumor status (pT), nodal metastasis, a increment of histopathological grade, vascular/perineural infiltration, and a high mitotic activity were positively associated with both poorer disease-specific and metastasis-free survival rates (all P < .05). In the multivariate analysis, a stepwise advancement of the pT status and high mitotic activity were significantly associated with poorer disease-specific and metastasis-free survival rates (all P < .05). By contrast, perineural invasion independently predicted only DSS rates, but not MeFS rates, in patients with UCUB (P = .018).

Table 4.

Univariate log-rank and multivariate analyses for Disease-specific and Metastasis-free Survivals in urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma.

| Parameter | Category | Case No. | Disease-specific Survival | Metastasis-free Survival | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

| No. of event | p-value | R.R. | 95% C.I. | p-value | No. of event | p-value | R.R. | 95% C.I. | p-value | |||

| Gender | Male | 216 | 41 | 0.4446 | - | - | - | 60 | 0.2720 | - | - | - |

| Female | 79 | 11 | - | - | - | 16 | - | - | - | |||

| Age (years) | < 65 | 121 | 17 | 0.1136 | - | - | - | 31 | 0.6875 | - | - | - |

| ≥ 65 | 174 | 35 | - | - | - | 45 | - | - | - | |||

| Primary tumor (T) | Ta | 84 | 1 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.006* | 4 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.019* |

| T1 | 88 | 9 | 2.865 | 1.299-6.329 | 23 | 4.177 | 1.216-14.343 | |||||

| T2-T4 | 123 | 42 | 11.764 | 1.344-100 | 49 | 5.208 | 1.487-18.234 | |||||

| Nodal metastasis | Negative (N0) | 266 | 41 | 0.0002* | 1 | - | 0.859 | 61 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.099 |

| Positive (N1-N3) | 29 | 11 | 1.066 | 0.524-2.169 | 15 | 1.689 | 0.906-3.149 | |||||

| Histological grade | Low grade | 56 | 2 | 0.0013* | 1 | - | 0.886 | 5 | 0.0007* | 1 | - | 0.685 |

| High grade | 239 | 50 | 0.892 | 0.187-4.264 | 71 | 0.799 | 0.269-2.368 | |||||

| Vascular invasion | Absent | 246 | 37 | 0.0024* | 1 | - | 0.119 | 54 | 0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.977 |

| Present | 49 | 15 | 0.574 | 0.286-1.154 | 22 | 0.991 | 0.534-1.838 | |||||

| Perineural invasion | Absent | 275 | 44 | 0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.018* | 66 | 0.0007* | 1 | - | 0.112 |

| Present | 20 | 8 | 2.805 | 1.197-6.574 | 10 | 1.834 | 0.868-3.878 | |||||

| Mitotic rate (per 10 high power fields) | < 10 | 139 | 12 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.011* | 23 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | 0.022* |

| >= 10 | 156 | 40 | 2.379 | 1.220-4.640 | 53 | 1.828 | 1.092-3.059 | |||||

| C1s expression | Low | 147 | 3 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | <0.001* | 16 | <0.0001* | 1 | - | <0.001* |

| High | 148 | 49 | 11.441 | 3.478-37.628 | 60 | 2.984 | 1.661-5.361 | |||||

* Statistically significant

Prognostic Significance of C1s Immunoreactivity in UCUTs and UCUBs

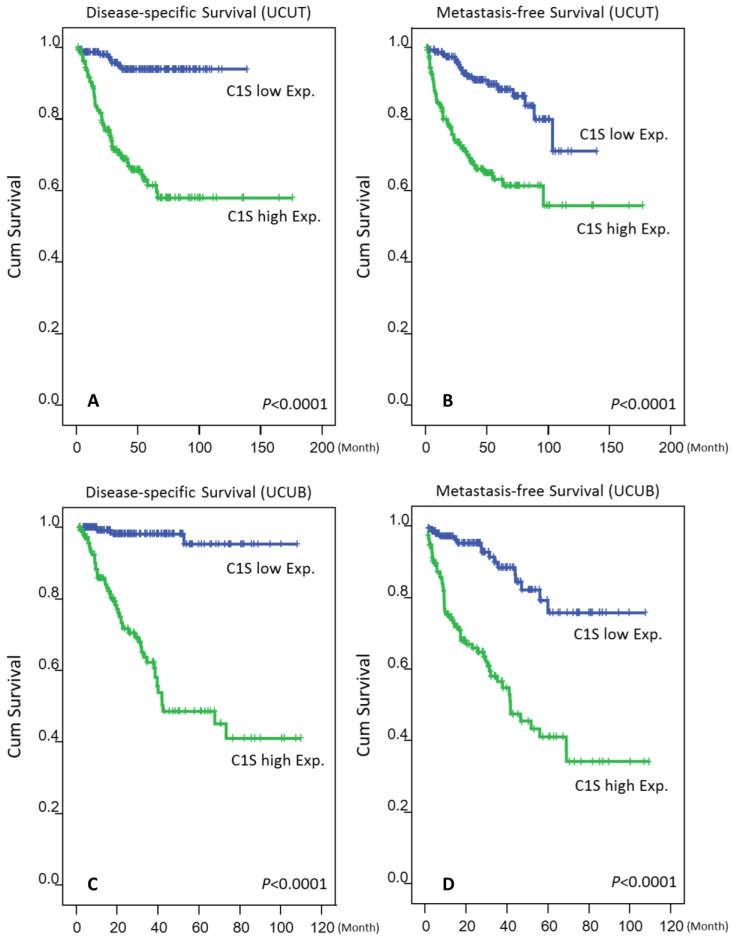

As shown in Tables 3 and 4 and Fig. 4, a high C1s expression level confers significant poor DSS and MeFS for both groups in the univariate analysis (all P < .0001). Moreover, C1s overexpression independently predicted poor DSS and MeFS rates for all UC patients in the multivariate analysis (all P < .01).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier plots revealed the significant prognostic value of C1s expression for disease-specific survival (DSS) and metastasis-free survival (MeFS) rates in the UCUT (A and B for DSS and MeFS, respectively) and UCUB (C and D for DSS and MeFS, respectively) groups (all P < .0001).

Discussion

UC is cancer type of cancer exhibiting high recurrence rates.22 The survival rate is also poor for patients with advanced disease.23,24 Hence, it is imperative for researchers to investigate new treatment targets in high-risk patients. Chronic inflammation participates in the tumorigenesis of certain cancers, including UC,25,26 by inducing cytokines, growth factors, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and others.14 ROS cause oxidative stress and an oxidation-reduction imbalance. The downregulation of certain proteins causing oxidative stress is also associated with poor prognosis in both UCUT and UCUB.27 By subjecting a published transcriptomic database (GSE31684) of UCUBs to data mining and focusing on peptidase activity (GO:0008233), we identified C1S as the most significantly upregulated gene related to advanced disease. In the ex vivo study, we also demonstrated that the upregulation and overexpression of C1S considering both mRNA and protein levels were associated with adverse clinicopathological parameters and also predicted poor prognosis in both UCUT and UCUB.

The complement system is a member of the innate immunity and plays a critical role in host defense. It contains a group of circulating glycoproteins that promote inflammation. The complement system comprises three major pathways: the classical, alternative, and mannan-binding lectin pathways.28 The classical pathway is triggered by the binding of the Fc region of antigen-bound antibody molecules to C1 components. The initial enzyme, C1, is a complex protein comprising one C1q molecule, two C1r molecules, and two C1s molecules. The molecular weight of C1s is 85 kDa, and its concentration in human plasma is approximately 50 μg/mL.18 C1s contains serine protease activity, which splits C4 and then C2 to generate C4b2a, also known as C3 convertase. As the cascade proceeds, a membrane attack complex is formed.

Although the complement system has been studied in certain malignant tumors and carcinogenesis,15-17 C1s is seldom investigated in cancers. Sakai et al. reported that when hamster complement C1s cDNA was transfected into BALB/c mouse fibroblast A31 cells, the transfectants formed tumors in BALB/c-nu/nu mice.29 In a subsequent study, the same authors transfected mutant C1s cDNA into A31 cells. However, the transfectants, which produced C1S without enzyme activity, did not form tumors in nude mice.30 In a recent study, the expression of C1S and other genes of the complement system was suppressed in paclitaxel-treated hypopharynx cancer cells.31 Furthermore, conformationally altered hyaluronan (HA) inhibited C1s activation and other components of the complement system in DU145 prostate cancer cells.32 The underexpression of HA synthase 3 (HAS3), one of the three HA synthases, is associated with adverse outcome and advanced disease in both UCUTs and UCUBs.33 These observations imply that C1s plays an essential role in carcinogenesis, and its expression in chemosensitive hypopharyngeal cancer cells can be suppressed through chemotherapy. The association between C1s and HAS3 is also intriguing. The underexpression of HAS3 resulting in a lower production of HA, a potential C1s suppressor, in addition to the overexpression of C1s may exert a synergistic effect on the carcinogenesis and tumor progression of both groups of UCs.

Conclusions

In summary, the present study demonstrated that C1s overexpression was not only indicators of unfavorable clinicopathological parameters but also independent prognostic factors that predict poor DSS and MeFS rates in patients with UCUTs or UCUBs. We have recently presented promising targets for new strategies in UC therapy.34-37 Therefore, additional studies must be conducted to elucidate the details of the biological significance of C1S and its encoded protein in UC oncogenesis for exploring the possible C1s-targeted therapy for both groups of UCs.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

C1s: complement component 1, s subcomponent

DSS: disease-specific survival

GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus

HA: hyaluronan

HAS: hyaluronan synthase

MeFS: metastasis-free survival

IRB: Institutional Review Board

ROS: reactive oxygen species

RT-PCR: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

UB: urinary bladder

UC: urothelial carcinoma

UT: upper urinary tract

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Kaohsiung Medical University “Aim for the Top Universities” (KMU-TP104E31, KMU-TP104G00, KMU-TP104G01, KMU-TP104G04), the health and welfare surcharge of tobacco products, Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW105-TDU-B-212-134007), Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST103-2314-B-037-059-MY3), and Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH-OR41, KMUH101-1R46). This work was also supported by grants from E-DA Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan (EDAHP105062) to I-W Chang

Ethical Standard

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Chi Mei Medical Center and E-DA Hospital, approval number IRB10302015 and EMRP-104-123, respectively. All samples were obtained from the BioBank of Chi Mei Medical Center and had been previously collected following official ethical guidelines. Informed consent has been obtained for those enrolled into BioBank.

Authors' Contributions

Conception and design: I-W Chang, A-C Liao, C-F Li; Development of methodology: V-C Lin, W-M Li, C-F Li; Acquisition of data: W-J Wu, P-I Liang, H-L He; Analysis and interpretation of data: B-W Yeh, C-F Li; Writing and/or revision of the manuscript: I-W Chang, C-F Li; Study supervision: W-J Wu, A-C Liao, C-F Li.

References

- 1.Lopez-Beltran A, Sauter G, Gasser T, et al. Infiltrating urothelial carcinoma. In: Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, et al., editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs, 3rd ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) press; 2004. p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z. et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raman JD, Messer J, Sielatycki JA. et al. Incidence and survival of patients with carcinoma of the ureter and renal pelvis in the USA, 1973-2005. BJU Int. 2011;107:1059–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan LB, Chen KT, Guo HR. Clinical and epidemiological features of patients with genitourinary tract tumour in a blackfoot disease endemic area of Taiwan. BJU Int. 2008;102:48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang MH, Chen KK, Yen CC. et al. Unusually high incidence of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma in Taiwan. Urology. 2002;59:681–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01529-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin JK, Silverman DT, Hsing AW. et al. Cigarette smoking and cancers of the renal pelvis and ureter. Cancer Res. 1992;52:254–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pommer W, Bronder E, Klimpel A. et al. Urothelial cancer at different tumour sites: role of smoking and habitual intake of analgesics and laxatives. Results of the Berlin Urothelial Cancer Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2892–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.12.2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinka T, Miyai M, Sawada Y. et al. Factors affecting the occurrence of urothelial tumors in dye workers exposed to aromatic amines. Int J Urol. 1995;2:243–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1995.tb00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debelle FD, Vanherweghem JL, Nortier JL. Aristolochic acid nephropathy: a worldwide problem. Kidney Int. 2008;74:158–69. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart JH, Hobbs JB, McCredie MR. Morphologic evidence that analgesic-induced kidney pathology contributes to the progression of tumors of the renal pelvis. Cancer. 1999;86:1576–82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991015)86:8<1576::aid-cncr27>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z, Furge KA, Yang XJ. et al. Comparative gene expression profiling analysis of urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis and bladder. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:58. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catto JW, Yates DR, Rehman I. et al. Behavior of urothelial carcinoma with respect to anatomical location. J Urol. 2007;177:1715–20. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vesely MD, Kershaw MH, Schreiber RD. et al. Natural innate and adaptive immunity to cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:235–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y, Antony S, Meitzler JL. et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying chronic inflammation-associated cancers. Cancer Lett. 2014;345:164–73. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suryawanshi S, Huang X, Elishaev E. et al. Complement pathway is frequently altered in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6163–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imamura T, Yamamoto-Ibusuki M, Sueta A, Influence of the C5a-C5a receptor system on breast cancer progression and patient prognosis. Breast Cancer; 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI 10.1007/s12282-015-0654-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao L, Zhang Z, Lin J. et al. Complement receptor 1 genetic variants contribute to the susceptibility to gastric cancer in Chinese population. J Cancer. 2015;6:525–30. doi: 10.7150/jca.10749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massey HD, McPherson RA. Mediators of Inflammation: Complement, Cytokines, and Adhesion Molecules. In: McPherson RA, Pincus MR, editors. Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods, 21st ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 849–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larrinaga G, Perez I, Sanz B. et al. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV activity is correlated with colorectal cancer prognosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papagerakis P, Pannone G, Zheng LI. et al. Clinical significance of kallikrein-related peptidase-4 in oral cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1861–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan EW, Li CC, Wu WJ. et al. FGF7 Over Expression is an Independent Prognosticator in Patients with Urothelial Carcinoma of the Upper Urinary Tract and Bladder. J Urol. 2015;194:223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodríguez-Alonso A, Pita-Fernández S, González-Carreró J. et al. Multivariate analysis of survival, recurrence, progression and development of mestastasis in T1 and T2a transitional cell bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:1677–84. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitra AP, Quinn DI, Dorff TB. et al. Factors influencing post-recurrence survival in bladder cancer following radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2012;109:846–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HS, Piao S, Moon KC. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy correlates with improved survival after radical cystectomy in patients with pT3b (macroscopic perivesical tissue invasion) bladder cancer. J Cancer. 2015;6:750–8. doi: 10.7150/jca.12259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng DF, Hu TL, Soutto M. et al. Glutathione peroxidase 7 suppresses bile salt-induced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in Barrett's carcinogenesis. J Cancer. 2014;5:510–7. doi: 10.7150/jca.9215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nesi G, Nobili S, Cai T. et al. Chronic inflammation in urothelial bladder cancer. Virchows Arch. 2015;467:623–33. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1820-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang IW, Lin VC, Hung CH. et al. GPX2 underexpression indicates poor prognosis in patients with urothelial carcinomas of the upper urinary tract and urinary bladder. World J Urol. 2015;33:1777–89. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merle NS, Church SE, Fremeaux-Bacchi V. et al. Complement System Part I - Molecular Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Front Immunol. 2015;6:262. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakai N, Kusunoki M, Nishida M. et al. Tumorigenicity of BALB3T3 A31 cells transfected with hamster-complement-C1s cDNA. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:309–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakiyama H, Nishida M, Sakai N. et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of hamster complement C1S: characterization with an active form-specific antibody and possible involvement of C1S in tumorigenicity. Int J Cancer. 1996;66:768–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960611)66:6<768::AID-IJC10>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu CZ, Shi RJ, Chen D. et al. Potential biomarkers for paclitaxel sensitivity in hypopharynx cancer cell. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2745–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong Q, Kuo E, Schultz L. et al. Conformationally altered hyaluronan restricts complement classical pathway activation by binding to C1q, C1r, C1s, C2, C5 and C9, and suppresses WOX1 expression in prostate DU145 cells. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19:173–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang IW, Liang PI, Li CC. et al. HAS3 underexpression as an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract and urinary bladder. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:5441–50. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3210-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang IW, Wang YH, Wu WJ. et al. Necdin overexpression predicts poor prognosis in patients with urothelial carcinomas of the upper urinary tract and urinary bladder. J Cancer. 2016;7:304–13. doi: 10.7150/jca.13638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang IW, Wu WJ, Wang YH. et al. BCAT1 overexpression is an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with urothelial carcinomas of the upper urinary tract and urinary bladder. Histopathology. 2016;68:520–32. doi: 10.1111/his.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang IW, Lin VC, He HL. et al. CDCA5 overexpression is an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with urothelial carcinomas of the upper urinary tract and urinary bladder. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:710–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma LJ, Wu WJ, Wang YH. et al. SPOCK1 overexpression confers a poor prognosis in urothelial carcinoma. J Cancer. 2016;7:467–76. doi: 10.7150/jca.13625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]