Abstract

Objectives

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) are routinely used to elicit patient preferences to improve health outcomes and healthcare services. While many fractional factorial designs can be created, some are more statistically optimal than others. The objective of this simulation study was to investigate how varying the number of (1) attributes, (2) levels within attributes, (3) alternatives and (4) choice tasks per survey will improve or compromise the statistical efficiency of an experimental design.

Design and methods

A total of 3204 DCE designs were created to assess how relative design efficiency (d-efficiency) is influenced by varying the number of choice tasks (2–20), alternatives (2–5), attributes (2–20) and attribute levels (2–5) of a design. Choice tasks were created by randomly allocating attribute and attribute level combinations into alternatives.

Outcome

Relative d-efficiency was used to measure the optimality of each DCE design.

Results

DCE design complexity influenced statistical efficiency. Across all designs, relative d-efficiency decreased as the number of attributes and attribute levels increased. It increased for designs with more alternatives. Lastly, relative d-efficiency converges as the number of choice tasks increases, where convergence may not be at 100% statistical optimality.

Conclusions

Achieving 100% d-efficiency is heavily dependent on the number of attributes, attribute levels, choice tasks and alternatives. Further exploration of overlaps and block sizes are needed. This study's results are widely applicable for researchers interested in creating optimal DCE designs to elicit individual preferences on health services, programmes, policies and products.

Keywords: discrete choice experiment, conjoint analysis, patient preferences, design efficiency

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The statistical efficiency of various fractional factorial designs using full profiles was explored.

The study allows identification of optimal designs with reduced response burden for participants.

The results of this study can be used in designing discrete choice experiments (DCEs) studies to better elicit preferences for health products and services.

Statistical efficiency of partial profile designs was not explored.

Optimal DCE designs require a balance between statistical efficiency and response burden.

Introduction

Determining preferences of patients and healthcare providers is a critical approach to providing high-quality healthcare services. Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) are a relatively easy and inexpensive approach to determining the relative importance of aspects in decision-making related to health outcomes and healthcare services.1–15 DCEs have long been applied in market research,16–21 while health research has more recently recognised their usefulness. With increasing popularity and a wide variety of applications, few studies have investigated the effect of multiple design characteristics on the statistical efficiency of DCEs.

In practice, DCEs are presented as preference surveys where respondents are asked to choose from two or more alternatives. These alternatives are bundles of multiple attributes that describe real-world alternatives.22 They are randomly placed within choice tasks (ie, survey questions) to create a survey where participants are asked to choose their most preferred option. Based on the alternatives chosen, the value of participant preferences on each attribute and attribute level can then be measured using the random utility theory.22 The ratios of these utility measures are used to compare factors with different units.

For DCE designs exploring a large number of variables, where presenting all combinations of alternatives is not feasible, a fractional factorial design can be used to determine participant preferences. For example, Cunningham et al15 investigated the most preferred knowledge translation approaches among individuals working in addiction agencies for women. They investigated 16 different four-level knowledge dissemination variables in a preference survey of 18 choice tasks, three alternatives per choice task, and 999 blocks. Blocks are surveys containing a different set of choice tasks (ie, presenting different combinations of alternatives), where individuals are randomly assigned to a block.15 To create a full factorial design with 16 four-level attributes, a total of 4 294 967 296 (416) different hypothetical alternatives are needed. Cunningham et al created a design with 999 blocks of 18 choice tasks and three alternatives per choice task. In total, this was a collection of 53 946 hypothetical scenarios, <1% of all possible scenarios.

When a small fraction of all possible scenarios is used in a DCE, biased results may occur due to how evenly attributes are represented. A full-factorial design presents all possible combinations of attributes and attribute-levels to participants. Such a design achieves optimal statistical efficiency; however, it is not usually practical or feasible to implement. Fractional factorial designs are pragmatic and present only a fraction of all possible choice tasks, but statistical efficiency is compromised in the process. The goodness of a fractional factorial design is often measured by relative design efficiency (d-efficiency), a function of the variances and covariances of the parameter estimates.23 A design is considered statistically efficient when its variance–covariance matrix is minimised.23 Poorly designed DCEs may lead to poor data quality, potentially leading to less reliable statistical estimates or erroneous conclusions. A less efficient design may also require a larger sample size, leading to increased costs.24 25 Investigating DCE design characteristics and their influence on statistical efficiency will aid investigators in determining appropriate DCE designs.

Previous studies have taken various directions to explore statistical efficiency, either empirically or with simulated data. These approaches (1) identified optimal designs using specific design characteristics,26–28 (2) compared different statistical optimality criteria,29 30 (3) explored prior estimates for Bayesian designs31–34 and (4) compared designs with different methods to construct a choice task (such as random allocation, swapping, cycling, etc).25 29 35–37 Detailed reports have been produced to describe the key concepts behind DCEs such as their development, design components, statistical efficiency and analysis.38 39 However these reports did not address the effect of having more attributes or more alternatives on efficiency.

To assess previous work in this area, we conducted a literature review of DCE simulation studies. Details are reported in box 1. In our search, the type of outcome differed across studies, making it difficult to compare results and identify patterns. We focused on relative d-efficiency (or d-optimality) and also reviewed a couple of studies that reported d-error, an inverse of relative d-efficiency.40 41 Of the studies reviewed, the various design characteristics explored by simulation studies are presented in table 1. Within each study, only two to three characteristics were explored. The number of alternatives investigated ranged from 2 to 5, attributes from 2 to 12, and attribute levels from 2 to 7. Only one study compared different components of blocks.42 To our knowledge, no study has investigated the impact of multiple DCE characteristics with pragmatic ranges on statistical efficiency.

Box 1. Search strategy for reviews on applications of DCEs in health literature.

A systematic search was performed using the following databases and search words. Snowball sampling was also performed in addition to the systematic search.

Databases searched:

JSTOR, Science Direct, PubMed and OVID.

Search words (where possible, given restrictions of each database)

dce,

discrete choice,

discrete-choice,

discrete choice experiment(s),

discrete choice conjoint experiment(s),

discrete choice modelling/modelling,

choice behaviour,

choice experiment,

conjoint analysis/es,

conjoint measurement,

conjoint choice experiment(s),

latent class,

stated preference(s),

simulation(s),

simulation study,

simulated design(s),

design efficiency,

d-efficiency,

design optimality,

d-optimality,

relative design efficiency,

relative d-efficiency,

relative efficiency.

Table 1.

Design characteristics investigated by simulation studies

| First author, year |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design characteristic | Street28 2002 | Kanninen27 2002 | Demirkale42 2013 | Graßhoff47 2013 | Louviere24 2008 | Crabbe40 2012 | Vermeulen48 2010 | Donkers41 2003 | This study |

| Number of choice tasks | 8–1120* | 360 | Varied to achieve optimality | 4,8,16,32* | 16 | 9 | 2–20* | ||

| Number of alternatives | 2 | 2,3,5* | 2,3* | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2–5* |

| Number of attributes | 3–8* | 2,4,8* | 3–12* | 1–7* | 3–7* | 3 | 2,3* | 2 | 2–20* |

| Number of levels | 2 | 2 | 2–7* | 2 | 1,2 | 3 | 2 | 2–5* | |

| Number of blocks | 5 | ||||||||

| Sample size | 38–106* | 25, 250* | 50 | ||||||

| Outcome type | D-efficiency | D-optimality | Number choice sets to achieve d-optimality | D-efficiency | D-efficiency | D-error | Relative d-efficiency | D-error | Relative d-efficiency |

| Comments | Only 38 designs presented. | Attribute levels described by as lower and upper bound | Evaluate different components of blocks | Locally optimal designs created. Compared binary attributes with 1 quantitative attribute, swapped alternatives within choice sets | Variation of levels is referred to as level differences | Authors compared designs with and without covariate information | Compared best-worst mixed designs with designs that were: (1) random, (2) orthogonal, (3) with minimal overlap, (4) d-optimal and (5) utility neutral d-optimal design | Designs compared with a binary attribute with an even distributed vs a skewed distribution | Characteristics were individually varied, holding others constant, to explore their impact on relative d-efficiency |

*Design characteristic has been investigated.

The primary objective of this paper is to determine how the statistical efficiency of a DCE, measured with relative d-efficiency, is influenced by various experimental design characteristics including the number of: choice tasks, alternatives, attributes and attribute levels.

Methods

DCEs are attribute-based approaches that rely on two assumptions: (1) products, interventions, services or policies can be represented by their attributes (or characteristics); and (2) an individual's preferences depend on the levels of these attributes.14 Random allocation was used to place combinations of attributes and attribute levels into alternatives within choice tasks.

Process of creating multiple designs

To create each design, various characteristics of DCEs were explored to investigate their impact on relative d-efficiency. The basis of each characteristic's range was determined by literature reviews and systematic reviews of applications of DCEs (table 2). The reviews covered DCE studies from 1990 to 2013, exploring areas such as economic evaluations, transportation and healthcare. The number of choice tasks per participant was most frequently 20 or less, with 16 or fewer attributes, between two and seven attribute levels, and between two and six alternatives. While the presence of blocks was reported, however, the number of blocks in each study was not.

Table 2.

Summary of items reported by reviews of DCEs

| First author | Ryan13 | Lagarde49 | Marshall1 | Bliemer44 | de Bekker-Grob3 | Mandeville2 | de Bekker-Grob25 | Clark50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of reviews | ||||||||

| Year reported | 2003 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 |

| Years covered | 1990–2000 | No time limit | 2005–2008 | 2000–2009 | 2001–2008 | 1998–2013 | 2012 | 2009–2012 |

| Literature review (LR) or systematic review (SR) | LR | LR | SR | LR | SR | SR | LR | SR |

| Specialities, areas covered in review | Healthcare, economic evaluations, other (eg, insurance plans) | Health workers | Disease-specific primary health studies | Tier 1 transportation journals | Health economics, QALY | Labour market preferences of health workers/human resources for health | Sample size calculations for healthcare-related DCE studies | Health-related DCEs |

| Total number of studies assessed | 34 | 10 | 79 | 61 | 114 | 27 | 69 | 179 |

| Items reported | ||||||||

| Number of choice tasks given to each participant | <8, 9–16, >16, not reported (mode=9–16) | Only reported mode 16 | 2–35, not reported (mode=7) | 1–20, not reported (mode=8,9) (total across all blocks: 3–46) | <8, 9–16, >16, not reported (mode ≤8) | <10–20 (mode=16–20) | ≤8 to ≥16, not reported (mode=9–16) | <9 to >16 (mode=9–16) |

| Number of attributes | 2–24 (mode=6) | 5–7 | 3–16 (mode=6, 70% between 3 and 7) | 2–30 (mode=5) | 2 to >10 | 5–8 | 2–9, >9 (mode=6) | 2–>10 (mode=6) |

| Number of levels within attributes | 2–6 | 2,3 | 2–7 | 2–4 (mode=2) | ||||

| Number of alternatives | 2, >2 | 2 | 2–6 | 2 | 2–4 | |||

| Number of blocks | Blocking reported, number of blocks not reported | Blocking reported, number of blocks not reported | ||||||

| Reported DCEs using Bayesian methods | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Design type: 1=full-factorial 2=fractional factorial 3=not reported |

1, 2, 3 | 2 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | 2 | 1, 2, 3 | ||

| Sample size | 13–1258 | 20–5829 | 102–3727 | <100 to >1000 | ||||

| Overlaps in alternatives | Yes | |||||||

| Number of simulation studies | ||||||||

| Response rates | <30–100% | 16.8–100% | ||||||

| Comments | Comparison with old SR (an updated SR) | A systematic update of Lagarde et al's49 study | Sample size paper | This is a systematic update of de Bekker- Grob et al's3 study | ||||

Using the modes of design characteristics from these reviews, we simulated 3204 DCE designs. A total of 288 (18×4×4=288) designs were created to determine how relative d-efficiency varied with 2–20 attributes, 2–5 attribute levels, and 2–5 alternatives. Each of the 288 designs had 20 choice tasks. We then continued to explore designs with different numbers of choice tasks. A total of 2916 (18×18×3×3=2916) designs were created that ranged with choice tasks from 2 to 20, attributes from 2 to 20, attribute levels from 2 to 4 and alternatives from 2 to 4.

Generating full or fractional factorial DCE designs in SAS V.9.4

The generation of full and fractional factorial designs was created using generic attributes in V.9.4 SAS software (Cary, North Carolina, USA). Four built-in SAS macros (%MktRuns, %MktEx, %MktLab and %ChoiceEff) are typically used to randomly allocate combinations of attributes and attribute levels to generate optimal designs.43 The %MktEx macro was used to create hypothetical combinations of attributes and attribute levels in a linear arrangement. Alternatives were added with %MktLab, results were assessed and then transformed into a choice design using %ChoiceEff.43

Evaluating the optimality of the DCE design

To evaluate each choice design, the goodness or efficiency of each experimental design was measured using relative d-efficiency. It ranges from 0% to 100% and is a relative measure of hypothetical orthogonal designs. A d-efficient design will have a value of 100% when it is balanced and orthogonal. Values between 0% and 100% indicate that all parameters are estimable, however, will have less precision than an optimal design. D-efficiency measures of 0 indicate that one or more parameters cannot be estimated.43 Designs are balanced when the levels of attributes appear an equal number of times in choice tasks.3 43 Designs are orthogonal when there is equal occurrence of each possible pair of levels across all pairs of attributes within the design.43 Since full factorial designs present all possible combinations of attributes and attribute levels, they are always balanced and orthogonal with a 100% d-efficiency measure. Fractional factorial designs present only a portion of these combinations, creating variability in statistical efficiency.

Results

A total of 3204 simulated DCE designs were created, varying by several DCE design characteristics. Using these designs, we present the impact of each design characteristic on relative d-efficiency by the number of alternatives, attributes, attribute levels and choice tasks in a DCE, respectively.

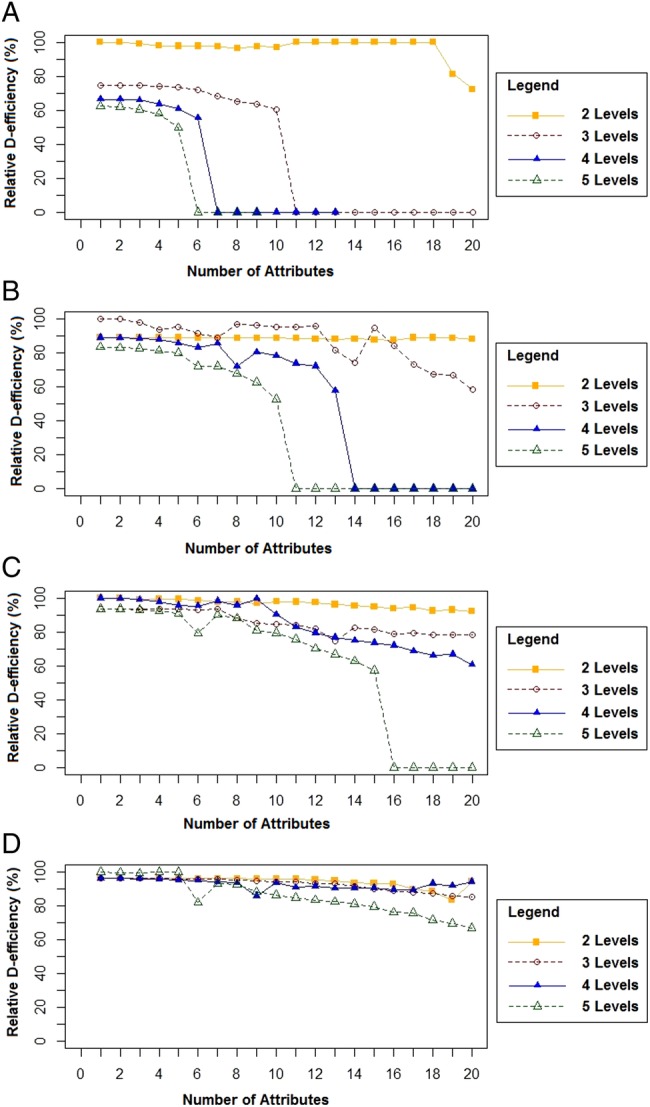

Relative d-efficiency increases with more alternatives per choice task in a design. This was consistent across all designs with various numbers of attributes, attribute levels and choice tasks. Figure 1A–D displays this change in statistical optimality for designs with two, three, four and five alternatives ranging from 2-level to 5-level attributes, 2 to 20 attributes, and a choice set size of 20. The same effect is found on designs across all choice set sizes ranging from 2 to 20.

Figure 1.

(A) Relative d-efficiencies (%) of designs with two alternatives across 2–20 attributes, 2–5 attribute levels and 20 choice sets each. (B) Relative d-efficiencies (%) of designs with three alternatives across 2–20 attributes, 2–5 attribute levels and 20 choice sets each. (C) Relative d-efficiencies (%) of designs with four alternatives across 2–20 attributes, 2–5 attribute levels and 20 choice sets each. (D) Relative d-efficiencies (%) of designs with five alternatives across 2–20 attributes, 2–5 attribute levels and 20 choice sets each.

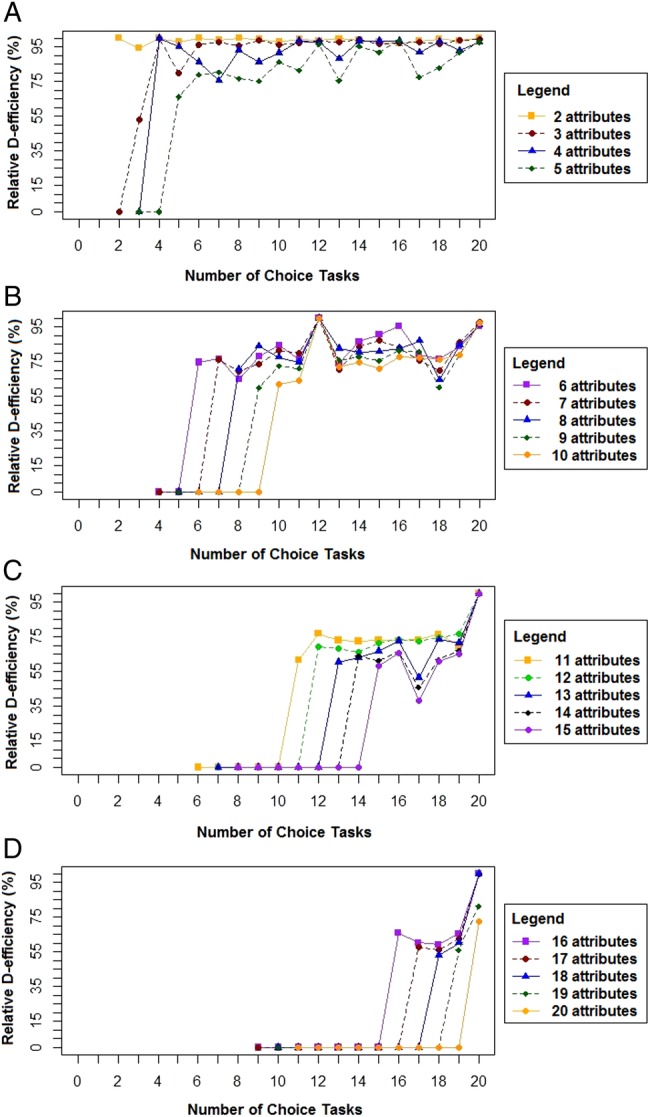

As the number of attributes increases, relative d-efficiency decreases, and in some cases designs were not producible. Designs with a larger number of attributes could not be created with a small number of alternatives or choice tasks. Figure 2A displays the decline in relative d-efficiency with DCEs ranging from two to five attributes across 2 to 20 choice tasks. Figure 2B–D illustrates a larger decline in relative d-efficiency as attribute size increases from 6 to 10, 11 to 15 and 16 to 20, respectively. Designs with choice tasks less than 11 were not possible in these examples.

Figure 2.

(A) The effect of 2–5 attributes on relative d-efficiency (%) across different choice tasks for designs with two alternatives and two-level attributes. (B) The effect of 6–10 attributes on relative d-efficiency (%) across different choice tasks for designs with two alternatives and two-level attributes. (C) The effect of 11–15 attributes on relative d-efficiency (%) across different choice tasks for designs with two alternatives and two-level attributes. (D) The effect of 16–20 attributes on relative d-efficiency (%) across different choice tasks for designs with two alternatives and two-level attributes.

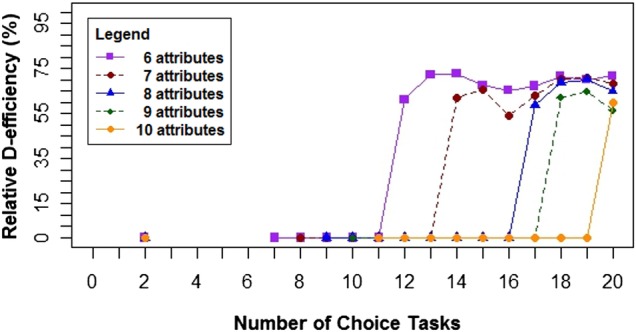

Similarly, from comparing figure 2B with figure 3, as the number of attribute levels increase, relative d-efficiency decreases across all designs with varying numbers of attributes, choice tasks and alternatives. DCEs with binary attributes (figure 2B) consistently performed well with all relative d-efficiencies above 80% except for designs with 18 or more attributes.

Figure 3.

The effect of 6–10 attributes on relative d-efficiency (%) across different choice tasks for designs with two alternatives and three-level attributes.

As the number of choice tasks in a design increases, d-efficiency increases and may plateau, where this plateau may not reach 100% statistical efficiency. This was observed across all attributes and attribute levels. Relative d-efficiency peaked at designs with a specific number of choice tasks, particularly when the number of alternatives was equal to or a multiple of the number of attribute levels and the number of choice tasks. This looping pattern of peaks begins only at large choice set sizes for designs with a large number of attributes. For example, among designs with two alternatives and two-level attributes, peaks were observed for designs with choice set sizes as small as 2 (figure 2A,B). For designs with three alternatives and three-level attributes, this looping pattern appeared at choice set sizes of 3, 9, 12, 15 and 18, depending on how much larger or smaller the number of attributes was.

Discussion

A total of 3204 DCE designs were evaluated to determine the impact of the different numbers of alternatives, attributes, attribute levels, and choice tasks on the relative d-efficiency of a design. Designs were created by varying one characteristic while holding others constant. Relative d-efficiency increased with more alternatives per choice task in a design, but decreased as the number of attributes and attribute levels increased. When the number of choice tasks in a design increased, d-efficiency would either increase or plateau to a maximum value, where this plateau may not reach 100% statistical efficiency. A pattern of peaks in 100% relative d-efficiency occurred for many designs where the number of alternatives was equal to, or a multiple of, the number of choice tasks and attribute levels.

The results of this simulation study are in agreement with other methodological studies. Sandor et al35 showed that DCE designs with a larger number of alternatives (three or four) performed more optimally using Monte Carlo simulations, relabelling, swapping and cycling techniques. Kanninen et al27 emphasise the use of binary attributes and suggest optimal designs, regardless of the number of attributes. We observed a pattern where many designs achieved statistical optimality, and when the number of choice tasks is a multiple of the number of alternatives and attribute levels, relative d-efficiency will peak to 100%. Johnson et al38 similarly discuss how designs require the total number of alternatives to be divisible by the number of attribute levels to achieve balance, a critical component of relative d-efficiency.

While fewer attributes and attribute levels were found to yield higher relative d-efficiency values, there is a lot of variability among applications of DCE designs (table 2). In our assessment of literature and systematic reviews from 2003 to 2015, some DCEs evaluated up to 30 attributes or 7 attribute levels.44 De Bekker-Grob et al3 observed DCEs within health economics literature between two time periods: 1990–2000 and 2001–2008. The total number of applications of DCEs increased from 34 to 114, while the proportions among design characteristics were similar. A majority of designs used 4–6 attributes (55% in 1990–2000, 70% in 2001–2008). In the 1990s, 53% used 9–16 choice tasks per design. This reduced to 38% in the 2000s with more reporting only eight or less choice tasks per design. While d-efficiency is advocated as a criterion for evaluating DCE designs,45 it was not commonly reported in the studies (0% in 1990–2000, 12% in 2001–2008). Other methods used to achieve orthogonality were single profiles (with binary choices), random pairing, pairing with constant comparators, or a fold-over design. Following this study, de Bekker-Grob performed another review in 2012 of 69 healthcare-related DCEs, where 68% used 9–16 choice tasks and only 20% used 8 or less.25 Marshall et al's review reported many DCEs created designs with six or fewer attributes (47/79), 7–15 choice tasks (54/79), with two-level (48/79) or three-level (42/79) attributes. Among these variations, de Bekker-Grob et al3 mention 37% of studies (47/114) did not report sufficient detail of how choice sets were created, which leads us to question if there is a lack of guidance in the creation and reporting of DCE designs.

This simulation study explores the statistical efficiency of a variety of both pragmatic and extreme designs. The diversity in our investigation allows for an easy assessment of patterns in statistical efficiency that is affected by specific characteristics of a DCE. We found that designs with binary attributes or a smaller number of attributes had better relative d-efficiency measures, which will also reduce cognitive burden, improve choice consistency and overall improve respondent efficiency. We describe the impact of balance and orthogonality on d-efficiency by the looping pattern observed as the number of choice tasks increase. We also link our findings with what has been investigated among other simulation studies and applied within DCEs. This study's results complement the existing information on DCE in describing the role each design characteristic has on statistical efficiency.

There are some key limitations to our study that are worth discussing. Multiple characteristics of a DCE design were explored, however, further attention is needed to assess all influences on relative d-efficiency. First, the number of overlaps, where the same attribute level is allowed to repeat in more than one alternative in a choice task, was not investigated. The presence of overlaps helps participants by reducing the number of comparisons they have to make. In SAS, the statistical software we used in creating our DCE designs, we were only able to specify whether or not overlaps were allowed. We were not able to specify the number of overlaps within a choice task or design so we did not include it in our analysis. Second, sample size was not explored. A DCE's statistical efficiency is directly influenced by the asymptotic variance–covariance matrix, which also affects the precision of a model's parameter estimates, and thus has a direct influence on the minimum sample size required.25 Sample size calculations for DCEs need several components including the preferred significance level (α), statistical power level (1-β), statistical model to be used in the DCE analysis, initial belief about the parameter values and the DCE design.25 Since the aim of this study was to identify statistically optimal DCE designs, we did not explore the impact of relative d-efficiency on sample size. Third, attributes with different levels (ie, asymmetric attributes or mixed-attribute designs) were not explored to compare with Burgess et al's26 findings. Best–worst DCEs were also not investigated. Last, we did not assess how d-efficiency may change when specifying a partial profile design to present only a portion of attributes within each alternative.

Several approaches can be made to further investigate DCE designs and relative d-efficiency. First, while systematic reviews exist on what designs are used and reported, none provide a review of simulation studies investigating statistical efficiency. Second, comparisons of optimal designs determined by different software and different approaches are needed to ensure there is agreement on statistically optimal designs. For example, the popular Sawtooth Software could be used to validate the relative d-efficiency measures of our designs. Third, further exploring the trade-off between statistical and informant (or respondent) efficiency will help tailor simulation studies to assess more pragmatic designs.46 Informant efficiency is a measurement error caused by participants' inattentiveness when choosing alternatives, or by other unobserved, contextual influences.38 Using a statistically efficient design may result in a complex DCE, increasing the cognitive burden for respondents and reducing the validity of results. Simplifying designs can improve the consistency of participants' choices which will help yield lower error variance, lower choice variability, lower choice uncertainty and lower variance heterogeneity.24 For investigators, it is best to consider balancing both statistical and informant efficiency when designing DCEs. Given our results, one approach to reduce design complexity we propose is to reduce the number of attributes and attribute levels, where possible, to identify an efficient and less complex design. Fifth, there is limited discussion of blocked DCEs among the simulation studies and reviews we explored. One study explored three different experimental designs (orthogonal with random allocation, orthogonal with blocking, and an efficient design), and found that blocking should be included in DCEs to improve the design.36 Other studies either mentioned that blocks were used with no additional details2 44 or only used one type of block size.42 In SAS, a design must first be created before it can be sectioned into blocks. From our investigation, varying the number of blocks, therefore, had no impact on relative d-efficiency since designs were sectioned into different blocks only after relative d-efficiency was measured. More information can be provided from the authors upon request. A more meaningful investigation is to explore variations in block size (ie, the number of choice tasks within a block). This will change the number of total choice tasks required and impact the relative d-efficiency of a DCE. Last, investigating other real-world factors that drive DCE designs are critical in ensuring DCEs achieve optimal statistical and respondent efficiency.

Conclusion

From the various designs evaluated, DCEs with a large number of alternatives and a small number of attributes and attribute levels performed best. Designs with binary attributes, in particular, had better statistical efficiency in comparison with other designs with various design characteristics. This study demonstrates that a fractional factorial design may achieve 100% statistical efficiency when the number of choice tasks is a multiple of the number of alternatives and attribute levels, regardless of the number of attributes. Further research needs to include investigation of the impact of overlaps, mixed attribute designs, best-worst DCEs and varying block sizes. These results are widely applicable in designing studies for determining individual preferences on health services, programmes and products. Clinicians can use this information to elicit participant preferences of therapies and treatments, while policymakers can identify what factors are important in decision-making.

Acknowledgments

Warren Kuhfeld from the SAS Institute Inc. provided programming guidance for DCE design creation.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors provided intellectual content for the manuscript and approved the final draft. TV contributed to the conception and design of the study; performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript; approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in relation to accuracy or integrity. LT contributed to the conception and design of the study; provided statistical and methodological support in interpreting results and drafting the manuscript; approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in relation to accuracy or integrity. CEC contributed to the conception and design of the study; critically assessed the manuscript for important intellectual content; approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in relation to accuracy or integrity. GF contributed to the interpretation of results; critically assessed the manuscript for important intellectual content; approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in relation to accuracy or integrity.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf. CEC's participation was supported by the Jack Laidlaw Chair in Patient-Centered Health Care.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: As this is a simulation study, complete results are available by emailing TV at thuva.vanni@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Marshall D, Bridges JF, Hauber B et al. . Conjoint Analysis Applications in Health—How are Studies being Designed and Reported? An Update on Current Practice in the Published Literature between 2005 and 2008. Patient 2010;3:249–56. 10.2165/11539650-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandeville KL, Lagarde M, Hanson K. The use of discrete choice experiments to inform health workforce policy: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:367 10.1186/1472-6963-14-367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ 2012;21:145–72. 10.1002/hec.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C et al. . Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1–186. 10.3310/hta5050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spinks J, Chaboyer W, Bucknall T et al. . Patient and nurse preferences for nurse handover-using preferences to inform policy: a discrete choice experiment protocol. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008941 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baji P, Gulácsi L, Lovász BD et al. . Treatment preferences of originator versus biosimilar drugs in Crohn's disease; discrete choice experiment among gastroenterologists. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016;51:22–7. 10.3109/00365521.2015.1054422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veldwijk J, Lambooij MS, van Til JA et al. . Words or graphics to present a Discrete Choice Experiment: does it matter? Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:1376–84. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCaffrey N, Gill L, Kaambwa B et al. . Important features of home-based support services for older Australians and their informal carers. Health Soc Care Community 2015;23:654–64. 10.1111/hsc.12185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veldwijk J, van der Heide I, Rademakers J et al. . Preferences for vaccination: does health literacy make a difference? Med Decis Making 2015;35:948–58. 10.1177/0272989X15597225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Böttger B, Thate-Waschke IM, Bauersachs R et al. . Preferences for anticoagulation therapy in atrial fibrillation: the patients’ view. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2015;40:406–15. 10.1007/s11239-015-1263-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams J, Bateman B, Becker F et al. . Effectiveness and acceptability of parental financial incentives and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing uptake of vaccinations in preschool children: systematic review, qualitative study and discrete choice experiment. Health Technol Assess 2015;19:1–176. 10.3310/hta19940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brett Hauber A, Nguyen H, Posner J et al. . A discrete-choice experiment to quantify patient preferences for frequency of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist injections in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;7:1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2003;2:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan M. Discrete choice experiments in health care: NICE should consider using them for patient centred evaluations of technologies. BMJ 2004;328:360–1. 10.1136/bmj.328.7436.360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham CE, Henderson J, Niccols A et al. . Preferences for evidence-based practice dissemination in addiction agencies serving women: a discrete-choice conjoint experiment. Addiction 2012;107:1512–24. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03832.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lockshin L, Jarvis W, d'Hauteville F et al. . Using simulations from discrete choice experiments to measure consumer sensitivity to brand, region, price, and awards in wine choice. Food Qual Preference 2006;17:166–78. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2005.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louviere JJ, Woodworth G. Design and analysis of simulated consumer choice or allocation experiments: an approach based on aggregate data. J Mark Res 1983;20:350–67. 10.2307/3151440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louviere JJ, Hensher DA. Using discrete choice models with experimental design data to forecast consumer demand for a unique cultural event. J Consum Res 1983:348–61. 10.1086/208974 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haider W, Ewing GO. A model of tourist choices of hypothetical Caribbean destinations. Leisure Sci 1990;12:33–47. 10.1080/01490409009513088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore WL. Levels of aggregation in conjoint analysis: an empirical comparison. J Mark Res 1980:516–23. 10.2307/3150504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darmon RY. Setting sales quotas with conjoint analysis. J Mark Res 1979;16:133–40. 10.2307/3150884 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Carson RT. Discrete choice experiments are not conjoint analysis. J Choice Model 2010;3:57–72. 10.1016/S1755-5345(13)70014-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhfeld WF, Tobias RD, Garratt M. Efficient Experimental Design with Marketing Research Applications. J Marketing Res 1994;31:545–57. 10.2307/3151882 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louviere JJ, Islam T, Wasi N et al. . Designing discrete choice experiments: do optimal designs come at a price? J Consumer Res 2008;35:360–75. 10.1086/586913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF et al. . Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient 2015;8:373–84. 10.1007/s40271-015-0118-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgess L, Street DJ. Optimal designs for choice experiments with asymmetric attributes. J Stat Plann Inference 2005;134:288–301. 10.1016/j.jspi.2004.03.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanninen BJ. Optimal design for multinomial choice experiments. J Marketing Res 2002;39:214–27. 10.1509/jmkr.39.2.214.19080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Street DJ, Burgess L. Optimal and near-optimal pairs for the estimation of effects in 2-level choice experiments. J Stat Plann Inference 2004;118:185–99. 10.1016/S0378-3758(02)00399-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose JM, Scarpa R. Designs efficiency for non-market valuation with choice modelling: how to measure it, what to report and why. Aus J Agricul Res Econ 2007;52:253–82. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessels R, Goos P, Vandebroek M. A comparison of criteria to design efficient choice experiments. J Marketing Res 2006;43:409–19. 10.1509/jmkr.43.3.409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandor Z, Wedel M. Designing conjoint choice experiments using managers’ prior beliefs. J Marketing Res 2001;38:430–44. 10.1509/jmkr.38.4.430.18904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrini S, Scarpa R. Designs with a priori information for nonmarket valuation with choice experiments: a Monte Carlo study. J Environ Econ Manag 2007;53:342–63. 10.1016/j.jeem.2006.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arora N, Huber J. Improving parameter estimates and model prediction by aggregate customization in choice experiments. J Consum Res 2001;28:273–83. 10.1086/322902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sándor Z, Wedel M. Heterogeneous conjoint choice designs. J Marketing Res 2005;42:210–18. 10.1509/jmkr.42.2.210.62285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sándor Z, Wedel M. Profile construction in experimental choice designs for mixed logit models. Mark Sci 2002;21:455–75. 10.1287/mksc.21.4.455.131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hess S, Smith C, Falzarano S et al. . Measuring the effects of different experimental designs and survey administration methods using an Atlanta managed lanes stated preference survey. Transportation Res Rec 2008;2049:144–52. 10.3141/2049-17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber J, Zwerina K. The importance of utility balance in efficient choice designs. J Marketing Res 1996;33:307–17. 10.2307/3152127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson F, Lancsar E, Marshall D et al. . Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health 2013;16:3–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li W, Nachtsheim CJ, Wang K et al. . Conjoint analysis and discrete choice experiments for quality improvement. J Qual Technol 2013;45:74. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crabbe M, Vandebroek M. Improving the efficiency of individualized designs for the mixed logit choice model by including covariates. Comput Stat Data Anal 2012;56:2059–72. 10.1016/j.csda.2011.12.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donkers B, Franses PH, Verhoef PC. Selective sampling for binary choice models. J Mark Res 2003;40:492–7. 10.1509/jmkr.40.4.492.19395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demirkale F, Donovan D, Street DJ. Constructing D-optimal symmetric stated preference discrete choice experiments. J Stat Plann Inference 2013;143:1380–91. 10.1016/j.jspi.2013.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuhfeld WF. Experimental design, efficiency, coding, and choice designs. Marketing Research methods in sas: Experimental design, choice, conjoint, and graphical techniques. Iowa State University: SAS Institute Inc 2005:53–241.

- 44.Bliemer MC, Rose JM. Experimental design influences on stated choice outputs: an empirical study in air travel choice. Transportation Res Part A Policy Pract 2011;45:63–79. 10.1016/j.tra.2010.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zwerina K, Huber J, Kuhfeld WF. A general method for constructing efficient choice designs. Durham, NC: Fuqua School of Business, Duke University, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patterson M, Chrzan K. Partial profile discrete choice: what's the optimal number of attributes. The Sawtooth Software Conference: 2003. Sequim, WA; 2003:173–85. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graßhoff U, Großmann H, Holling H et al. . Optimal design for discrete choice experiments. J Stat Plann Inference 2013;143:167–75. 10.1016/j.jspi.2012.06.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vermeulen B, Goos P, Vandebroek M. Obtaining more information from conjoint experiments by best–worst choices. Comput Stat Data Anal 2010;54:1426–33. 10.1016/j.csda.2010.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lagarde M, Blaauw D. A review of the application and contribution of discrete choice experiments to inform human resources policy interventions. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:62 10.1186/1478-4491-7-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S et al. . Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics 2014;32:883–902. 10.1007/s40273-014-0170-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]