Abstract

Spider poisoning is rare in Europe, with very few reported cases in the literature. Recluse spider (genus Loxosceles) bites may lead to cutaneous and systemic manifestations known as loxoscelism. We report the second known case of spider bite poisoning in Malta caused by Loxosceles rufescens (Mediterranean recluse spider). A young adult female presented with localised erythema and pain on her left thigh after a witnessed spider bite. Over a few days, the area developed features of dermonecrosis together with systemic symptoms, including fever, fatigue and a generalised erythematous eruption. She was managed by a multidisciplinary team and the systemic symptoms resolved within 6 days, while the skin lesion healed with scarring within 2 months. A recluse spider bite should be considered in patients with dermonecrosis. Although spider bite poisoning is uncommon in Europe, it is important to diagnose and manage it appropriately since it could lead to potentially serious sequelae.

Background

Spider bite poisoning is relatively uncommon in Europe where the Mediterranean recluse spider (Loxosceles rufescens) (figure 1) is the most dangerous arachnid to humans. The recluse spider is harmful as it can cause both cutaneous and systemic manifestations, referred to as cutaneous and systemic loxoscelism. Loxoscelism may lead to complications, including skin necrosis, acute renal failure, haemolysis, pulmonary oedema and rarely death. Although common in America where different species of Loxosceles exist, there are very few cases of recluse spider bites in Europe reported in the literature.1

Figure 1.

Mediterranean Recluse spider (Loxosceles rufescent) - total body length 6.0–7.5 mm. Photograph courtesy of Albert Gatt Floridia.

To date, there has been only one reported case of spider poisoning in Malta. This was caused by L. rufescens (the Mediterranean recluse spider).2 We report the second case of spider bite poisoning in Malta caused by the same species.

Case presentation

A young adult female presented to her local health centre reporting of pain, swelling and erythema over the lower part of the left thigh. The patient had been for a walk in nearby fields and after returning home suddenly felt a mild burning sensation on the lower part of her left thigh. When she rolled up her trousers she witnessed the live spider crawl away. She also found two spider legs on her trousers. A few hours later, the pain increased in severity with minimal erythema. She visited the local health centre and was given hydrocortisone 200 mg intravenous stat and prescribed levocetirizine 5 mg daily and doxycycline 100 mg two times a day. Results of the blood investigations, including complete blood count, renal profile and coagulation screen, were unremarkable. The following day she noticed increased erythema, and a central bluish discolouration was evident by the evening (figure 2A, B). Over the next few days, the pain, erythema and swelling increased considerably, and the bluish discolouration darkened as time progressed (figure 3). By the second day after the event, the patient developed myalgias, a fever of up to 99°F, and a widespread erythematous skin eruption and facial flushing. This persisted until the fouth day when the patient was seen by an infectious-disease consultant who advised stopping doxycycline. Over the next few days, the lesion developed a black necrotic centre and by day 6, tender erythema had spread below the knee making ambulation difficult. The patient was still febrile up to 100°F and was referred for a dermatological review. She was advised wound care with povidone-iodine dressing along with regular follow-up and analgesia. Over the next few days the lesion blistered and later ulcerated, while the surrounding erythema and pain subsided (figure 4). By day 41, the ulcer had scabbed and after 2 months, it healed with scarring (figure 5). The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon for review.

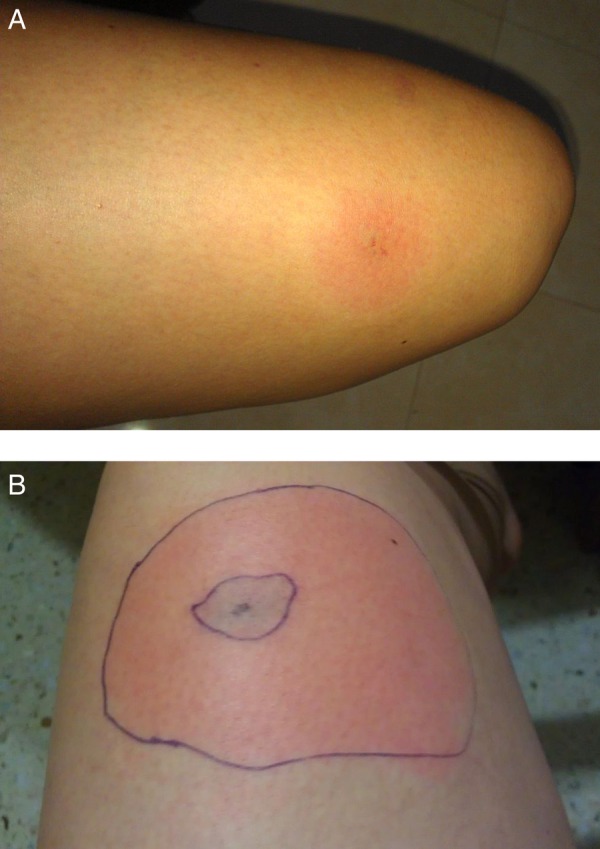

Figure 2.

(A) Day 1 (morning). (B) Day 1 (evening).

Figure 3.

Day 2.

Figure 4.

Day 15.

Figure 5.

2 months.

Investigations

Blood investigations, including a complete blood count, coagulation screen and renal profile, together with urinalysis and microscopy were taken to exclude potential life-threatening complications such as renal failure, haemolytic anaemia and disseminated intravascular coagulation. In our case, all the blood results were unremarkable.

Differential diagnosis

Recluse spider bites are rare in Europe. The differential diagnosis of the initial skin lesion included other commoner diagnosis such as herpes simplex, bacterial and fungal skin infections, and pyoderma gangrenosum. In this case, the generalised erythematous rash could have been an adverse reaction to doxycycline, although it was initially thought that the rash was more likely to be a systemic manifestation of the spider bite poisoning.

Treatment

Treatment of the initial systemic symptoms included paracetamol, hydrocortisone, levocetirizine and doxycycline. The patient was later prescribed codeine to control the pain. Cutaneous management was largely conservative and included local wound care with povidone-iodine dressings and regular dermatology follow-up.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient developed both cutaneous and systemic loxoscelism. Luckily the features were not life-threatening and the systemic symptoms resolved over a 2-week period. Cutaneous symptoms resolved within 2 months, leaving a small area of scarring.

Discussion

Recluse spiders of the genus Loxosceles are known as violin or fiddle-back spiders in view of a pigmented pattern present on the dorsal aspect of their cephalothorax. They can be distinguished from other spiders as they have six eyes arranged in pairs (dyads) while others typically contain eight eyes arranged in two rows. The violin or fiddle-shaped pattern is an unreliable way to distinguish them from other spiders as the degree of pigmentation may vary within species.3 The pattern may be completely absent in the European species (figure 1).

There are around 100 different species of the genus Loxosceles, the majority of which are found in temperate and tropical regions of America and Africa, with only one species in Europe. Different species are endemic to each continent. A MEDLINE search of the word ‘Recluse spider’ revealed several case reports of Loxosceles reclusa bites in North and South America, but few from the Mediterranean where L. rufescens is the culprit species.4 These case reports were documented in Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, Turkey, Greece and Israel.1 5–13 L. rufescens has also been reported from Balearic Islands, Corsica, Crete, Croatia and the Netherlands.14

Loxosceles spiders are infamous and unique as the spider bite may lead to ‘loxoscelism’ causing skin necrosis and possibly systemic features. This occurs as the spider venom contains an exclusive enzyme, sphingomyelinase D, which is only found in one other genus of spiders and various other bacteria. This enzyme is the main cause of dermonecrosis that occurs after envenomation.15

Most cases of recluse spider bites are recorded in the summer months when the spider appears to be more active; it generally tends to bite when the patient is either sleeping or putting on clothes. These spiders appear to have a predilection to bite on the trunk, thigh or arms, with the commonest site being the thigh.16 17 Both recorded cases in Malta occurred during the summer months, in June and July. The sites affected were the trunk and thigh.

Initially the spider bite is relatively painless and may go unnoticed; consequently, the culprit spider is only rarely captured. In our case, the patient distinctly remembered seeing the spider and with the help of a local entomologist matched its appearance to the recluse spider. She appeared to be a reliable historian with a tertiary level of education. In Malta, there is only one other spider whose toxin appears to be dangerous to humans, Steatoda paykulliana. However, this spider's bite only causes mild localised pain, and no dermonecrosis or systemic upset; also, this spider's bite morphologically looks very different from the described appearance. In the previous case recorded in Malta, the spider was actually captured and later identified as L. rufescens.2

Recluse spider bites can cause an array of symptoms ranging from a mild urticarial reaction to areas of dermonecrosis (cutaneous loxoscelism), and possibly to more serious systemic symptoms.

As in our case, a typical recluse spider bite starts off with a mild sting that subsides. After a few hours (2–8 hours), the area becomes intensely pruritic and painful, and the area around the bite develops an erythematous ring. Within 48 hours, central necrosis may occur starting off as an area of central cyanosis that may form a blister and ulcerate. This is typically described as the ‘red, white and blue sign’ due to the blue necrotic centre with a surrounding pale white border and erythema (figure 3). This results from the erythema, ischaemia and thrombosis that occur from the periphery to the centre.8

Skin lesions can be graded as mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2) or severe (grade 3). Mild lesions do not develop any necrosis while moderate and severe lesions develop necrosis which are <1 cm2 and >1 cm2, respectively. The commonest are grade 2 lesions, as in our case.

Lesions typically subside within 2–3 months and are very rarely fatal. However, resolution ultimately depends on the size of the lesion, age of the patient and presence of any comorbidities.17

Symptoms of systemic loxoscelism typically appear 2–3 days after the initial bite and may include high fever, malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, generalised non-specific rashes, nausea and vomiting, and possibly thrombocytopenia, haemolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation and renal failure.18 The severity of loxoscelism depends on a number of factors. These include: the amount of venom injected, the type of venom injected (the degree of sphingomyelinase D activity), the sex of the spider (female spiders are known to have more toxic venom), the site of the bite and the host's reaction to the venom.10 15 19

Rare complications of recluse spider bites include intravascular haemolysis and pulmonary oedema, with some rare cases reporting death.20 Despite this, fatalities from recluse spider bites have only been based on circumstantial evidence of a presumptive spider bite, and no fatal cases were reported where the spider was actually caught and identified.21 Furthermore, various case reports have shown that L. rufescens tends to cause milder symptoms compared to the more infamous L. reclusa. The latter may be arguable since recent in vitro and animal studies on the venom from L. rufescens has shown it to be of similar strength to that from other species such as L. reclusa.4,22

In the case described above, despite the fact that the spider was never caught for analysis, the clinical history and progression of the bite (as evidenced by the photographic time line provided) is typical of the recluse spider. The patient also distinctly remembered the spider as being different to other spiders found in Malta. Other factors that fit into the clinical picture of a recluse spider are the seasonality of the bite, the location of the bite and the fact that the similar time line of cutaneous events was also accompanied by systemic symptoms, suggesting that the patient may have developed both cutaneous and systemic loxoscelism. Also, as discussed earlier, in Malta there are only two spider species known to be toxic to humans and these have distinct morphological features; the other species' bite (S. paykulliana) only causes mild localised pain as opposed to the recluse spider bite.

Both recorded cases in Malta were characterised by mild systemic symptoms—fever, malaise and myalgia. Local dermonecrosis was the hallmark in both cases. However, in our case, conservative treatment was sufficient for healing while in the first recorded case, the cutaneous dermonecrosis required both conservative and surgical treatment with debridement. No biochemical disturbance was noted in either of the cases.2

Management of recluse spider bites is initially supportive with elevation, tetanus prophylaxis, local wound care with antiseptic dressing and pain relief. Cool compresses are particularly important in the initial phase as the activity of sphingomyelinase D is temperature dependent. Monitoring for systemic symptoms as well as blood investigations, particularly a complete blood count, renal profile and coagulation screen, and a urinalysis is necessary.

Medical treatment is largely empirical due to lack of human randomised controlled trials, and involves the use of antihistamines, corticosteroids, dapsone, colchicine and diphenydramine. Other treatments, including hyperbaric oxygen, nitroglycerin and antivenom, have been studied in animal models; however, none of these treatments has been shown to be clinically effective.3 18

Surgical excision and skin grafting may be necessary when the area of necrosis is substantial. However, this should not be performed in the acute phase since envenomation may persist for up to 2 weeks after the bite; thus, this should only be considered in severely necrotic wounds, where the necrotic edge is well demarcated.23

Learning points.

Although uncommon, recluse spider bites are potentially harmful and could cause both cutaneous and systemic symptoms known as loxoscelism.

Spider bite poisoning should be kept in mind as a potential cause of dermonecrosis if the other obvious causes are excluded as very often the culprit spider is not seen.

The importance of targeted investigations, such as blood and urine testing, to exclude potentially life-threatening sequelae such as haemolytic anaemia and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Although at present medical care is limited, the management by a multidisciplinary team, including a dermatologist, infectious disease consultant and tissue viability nurse, is recommended.

Recluse spider bites in the Mediterranean have been rarely reported, and in most cases there were no serious consequences. Thus, it is important to note that there is no cause for unnecessary alarm among the medical community and general public.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr David Dandria, a local entomologist, for his valuable advice, and Mr Albert Gatt Floridia for giving us a photograph of the Mediterranean recluse spider (Loxosceles rufescens)-figure 1.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

References

- 1.Rubenstein E, Stoebner PE, Herlin C et al. Documented cutaneous loxoscelism in the south of France: an unrecognized condition causing delay in diagnosis. Infection 2016;44:383–7. 10.1007/s15010-015-0869-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dandria D, Mahoney P. First record of spider poisoning in the Maltese Islands. The Central Mediterranean Naturalist 2002;3:173–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swanson DL, Vetter RS. Bites of brown recluse spiders and suspected necrotic arachnidism. N Engl J Med 2005;352:700–7. 10.1056/NEJMra041184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Planas E, Zobel-Thropp PA, Ribera C et al. Not as docile as it looks? Loxosceles venom variation and loxoscelism in the Mediterranean Basin and the Canary Islands. Toxicon 2015;93:11–19. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribuffo D, Serratore F, Famiglietti M et al. Upper eyelid necrosis and reconstruction after spider byte: case report and review of the literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012;16:414–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Entrambasaguas M, Plaza-Costa A, Casal J et al. Labial dystonia after facial and trigeminal neuropathy controlled with a maxillary splint. Mov Disord 2007;22:1355–8. 10.1002/mds.21488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coutinho I, Rocha S, Ferreira ME et al. [Cutaneous loxoscelism in Portugal: a rare cause of dermonecrosis]. Acta Med Port 2014;27:654–7. 10.20344/amp.4891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubiche T, Delaunay P, del Giudice P. A case of loxoscelism in southern France. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013;88:807–8. 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akdeniz S, Green JA, Stoecker WV et al. Diagnosis of loxoscelism in two Turkish patients confirmed with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and non-invasive tissue sampling. Dermatol Online J 2007;13:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yigit N, Bayram A, Ulasoglu D et al. Loxosceles spider bite in Turkey (Loxosceles rufescens, Sicariidae, Araneae). J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis 2008;14:178–87. 10.1590/S1678-91992008000100016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stefanidou MP, Chatzaki M, Lasithiotakis KG et al. Necrotic arachnidism from Loxosceles rufescens harboured in Crete, Greece. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:486–7. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01486.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen N, Sarafian DA, Alon I et al. Dermonecrotic Loxoscelism in the Mediterranean Region. J Toxicol: Cutan Ocul Toxicol 1999;18:75–83. 10.3109/15569529909049325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidovici BB, Pavel D, Cagnano E et al. , EuroSCAR; RegiSCAR study group. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis following a spider bite: report of 3 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:525–9. 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Peru A. The spiders of Europe Vol 1. Mémoires de la Societé Linéenne de Lyon No 2, 2011:110–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanson DL, Vetter RS. Loxoscelism. Clin Dermatol 2006;24:213–21. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gremski LH, Trevisan-Silva D, Ferrer VP et al. Recent advances in the understanding of brown spider venoms: from the biology of spiders to the molecular mechanisms of toxins. Toxicon 2014;83:91–120. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyachenko P, Ziv M, Rozenman D. Epidemiological and clinical manifestations of patients hospitalized with brown recluse spider bite. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:1121–5. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01749.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen RJ, Campoli J, Johar SK et al. Suspected brown recluse envenomation: a case report and review of different treatment modalities. J Emerg Med 2011;41:e31–7. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.08.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDade J, Aygun B, Ware RE. Brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) envenomation leading to acute hemolytic anemia in six adolescents. J Pediatr 2010;156:155–7. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatti AZ, Adeniran A, Salam S et al. Brown recluse spider bite to the leg. Injury Extra 2006;37:45–8. 10.1016/j.injury.2005.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sams HH, Dunnick CA, Smith ML et al. Necrotic arachnidism. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:561–73; quiz 73-6 10.1067/mjd.2001.112385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene A, Breisch NL, Boardman T et al. The Mediterranean Recluse Spider, Loxosceles rufescens (Dufour): an Abundant but Cryptic Inhabitant of Deep Infrastructure in the Washington DC. Area (Arachnida: Araneae: Sicariidae). Am Entomol 2009;55:158–69. 10.1093/ae/55.3.158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunnelee JD. Brown recluse spider bites: a case report. J Perianesth Nurs 2006;21:12–15. 10.1016/j.jopan.2005.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]