Abstract

Objectives

To explore whether pharmacokinetic (PK) studies in paediatric patients are becoming less invasive. This will be evaluated by analysing the number of samples and volume of blood collected for each study within four different decades.

Methods

A systematic literature review was performed to identify PK papers describing number of samples and volume of blood collected in studies of children aged 0–18 years. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (1946 to December 2015), EMBASE (1974 to December 2015), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to December 2015), CINAHL and Cochrane Library.

Results

A total of 549 studies were identified between 1974 and 2015. There were 52 studies between 1976 and 1985, 105 between 1986 and 1995, 201 between 1996 and 2005 and 191 between 2006 and 2015. The number of blood samples collected per participant increased between the first two decades (p=0.013), but there was a decrease in the number of samples in the subsequent two decades (p=0.044 and p<0.001, respectively). Comparing the first and last decades, there has been no change in the number of blood samples collected. There were no significant differences in volume collected per sample or total volume per child in any of the age groups. There was however a significant difference in the frequency of blood sampling between population PK studies (median 5 (IQR 3–7)) and non-population PK studies (median 8 (IQR 6–10); p=<0.001).

Conclusions

The number of blood samples collected for PK studies in children rose in 1985–1995 and subsequently declined. There was no overall change in the volume of blood collected over the 4 decades. The usage of population PK methods reduces the frequency of blood sampling in children.

Keywords: Blood, Sampling, Pharmacokinetics, Children

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A systematic literature review of published pharmacokinetic (PK) studies in children.

Comparison of number of blood samples, individual and total blood volume collected.

Some studies did not report the results for different paediatric age groups.

Some studies were limited by the lack of data on weight and volume.

Introduction

Clinical pharmacokinetics is the study of the relationships between drug dosage regimens and concentration–time profiles.1 These studies are essential in paediatric patients as they help determine the correct dose and regimen. While it is important to perform invasive clinical research in children, this should be done in an ethical manner.

Venepuncture is the most common invasive procedure within pharmacokinetic (PK) studies. This procedure has been shown to cause psychological and physical pain in children.2 The expectation of pain is a common psychological problem and may contribute to difficulty in blood sampling in children.3 Physiological implications of blood sampling, especially in preterm neonates, are that excessive blood sampling may compromise circulation and lead to a need for transfusion. Venepuncture may also cause physical risks such as bruising to the child4 and frequent sampling can be associated with infection.5 The choice of sampling site depends on the age, weight and the volume of blood required. Heel prick is usually done for infants <6 months old or between 3 and 10 kg. Finger prick can be used for children over 6 months and more than 10 kg.6

Adult PK studies cannot be used to determine paediatric characteristic; therefore, PK studies in children are essential. Children have a lower total blood volume (TBV) and tend not to tolerate pain. Invasiveness can be minimised by scavenging blood collected for diagnostic purpose and taking samples at the same time as clinical samples. Micro-samples have reduced the volumes of blood required for analysis, and several studies have demonstrated their usefulness in estimating PK parameters in neonates and children.7–9 Similarly, the technique of population-based parametric PK estimation has been used to facilitate fewer samples for each individual child.

Different guidelines on the safe limit for blood sampling have been proposed. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommends that not >3% of TBV of neonates should be withdrawn during a period of 4 weeks and at a single time, drawn blood should not exceed 1% of TBV.10 The US Department of Health and Human Services, on the other hand, recommends that not >3.8% (3 mL/kg) of the TBV should be withdrawn at once.11 The number of samples required for PK studies varies with the research question. There is no standard guideline on the frequency of blood sampling in children.

A review of invasiveness of PK studies in children has not been conducted. Therefore, our aim was to explore whether PK studies in paediatric patients are becoming less invasive. We therefore decided to perform a systematic review of frequency and volume of blood sampling in PK studies in paediatric patients and compare four decades.

Method

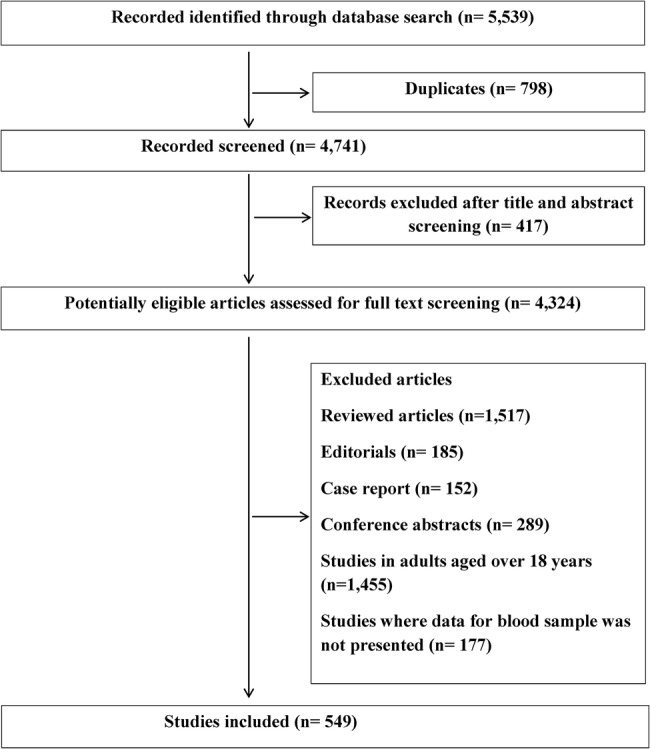

A systematic literature search was performed to identify all papers describing the number of samples and volume of blood collected in paediatric patients of all ages up to 18 years. The following databases were used: MEDLINE (1946 to December 2015), EMBASE (1974 to December 2015), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to December 2015), CINAHL and Cochrane Library (figure 1). The databases were searched separately and combined together to remove duplications. The search strategy included all languages and involved the keywords ‘preterm neonate*’ OR ‘term neonate*’ OR ‘neonate*’ OR ‘new-born*’ OR ‘child*’ OR children OR ‘p*ediatric*’ OR ‘infant*’ OR ‘adolescent*’12 AND ‘pharmacokinetic*’ OR blood OR plasma OR specimen OR serum OR blood sampling OR ‘blood sample*’ (see online supplementary table S1). After screening the abstract for duplicates and irrelevant studies, a further screening of full articles was performed. A manual reference search was conducted to identify previously undetected articles.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the search performed.

Search strategy for Embase 1974 to 2015

bmjopen-2015-010484supp_table.pdf (6.2KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria were original PK studies with documented number of blood samples in children up to the age of 18 years. We excluded review articles, editorials, conference abstracts and studies in adults aged 18 years and over. Studies where data for blood samples were not presented were also excluded. Data such as number of patients, age group, mean weight, number of blood samples, volume of blood per sample, total volume of blood, name of drug and year of study were extracted. One investigator performed the literature search and data extraction (MIA). All studies conducted between 1967 and 2015 were identified and comparison made between the four decades. Paediatric patients were grouped as (1) neonates (<28 days); (2) infants (28 days to under 2 years); (3) children (2–11 years); (4) adolescents (12 to under 18 years).13

Statistical analysis

The samples and volume for each decade under consideration were not normally distributed for some age groups. Therefore, the number of samples and volume for each decade were compared, using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The mean ranks of each column were subsequently compared using Dunn's post hoc tests. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 549 paediatric PK studies, which stated the numbers of blood samples collected, were identified between 1976 and 2015 (figure 1). A total of 177 studies did not state the number of blood samples collected (2 between 1976 and 1985, 55 between 1986 and 1995, 66 between 1996 and 2005, 54 between 2006 and 2015); these studies were excluded. There were 52 studies between 1976 and 1985, 105 between 1986 and 1995, 201 between 1996 and 2005 and 191 between 2006 and 2015 (table 1).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic studies in the four decades

| Age group | Number of studies (number of cannula studies) |

Number of patients |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976–1985 | 1986–1995 | 1996–2005 | 2006–2015 | 1976–1985 | 1986–1995 | 1996–2005 | 2006–2015 | |

| Neonates | 9 (1) | 18 (3) | 18 (4) | 8 (4) | 188 | 385 | 423 | 231 |

| Infants | 12 (3) | 6 (2) | 17 (6) | 11 (3) | 250 | 162 | 376 | 467 |

| Children | 20 (13) | 61 (20) | 102 (36) | 99 (32) | 301 | 1011 | 2826 | 5466 |

| Adolescents | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 11 (4) | 9 | 36 | 107 | 328 |

| Mixed age | 10 (2) | 16 (6) | 61 (17) | 62 (22) | 297 | 376 | 2468 | 3391 |

| Total | 52 (20) | 105 (33) | 201 (64) | 191 (68) | 748 | 1970 | 6200 | 9883 |

In total, 53 of the studies were neonatal studies, 46 involved infants, 282 involved children and 19 were adolescent studies. The per cent of studies that used an indwelling catheter ranged between 31% and 38% in each decade. Other sampling methods included arterial sampling (1%), heel prick (1%) and finger prick (2%). In 50% of studies, the method was not stated. A total of 194 studies involved paediatric patients across the whole age spectrum.

The total number of paediatric patients in PK studies has increased over each decade from 748 in the earliest decade to 9883 in the latest decade (table 1). The number of neonates increased each decade up to 2005. The number in the last decade however fell sharply.

Most studies were conducted in the USA (218), France (41) and the UK (39). There were 59 multinational studies.

The number of blood samples collected per paediatric patient was significantly higher in 1986–1995 than in any other decade (p<0.001; table 2).

Table 2.

Blood samples per paediatric patient

| Age group | Number of blood samples |

Statistical analysis (overall p value) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976–1985 Median [IQR] (range) |

1986–1995 Median [IQR] (range) |

1996–2005 Median [IQR] (range) |

2006–2015 Median [IQR] (range) |

||

| Neonates | 6 [5–7] (1–8) | 7 [6–9]* (1–14) | 4 [3–7]* (1–11) | 5 [3–7] (2–14) | 0.047 |

| Infants | 6.5 [5–7] (2–9) | 9 [6–11] (4–27) | 8 [5–12] (3–12) | 6 [4–8] (4–10) | 0.261 |

| Children | 7 [5–9]Î (4–20) | 9 [8–12]Ά (4–18) | 8 [7–10] (2–19) | 7 [5–9]† (2–20) | <0.001 |

| Adolescents | 5 | 8 [7–9] (7–9) | 9 [8–10] (8–10) | 6 [4–9] (2–11) | 0.300 |

| Mixed age | 8 [5–12] (5–18) | 9 [6–12] (2–15) | 8 [6–10] (1–16) | 7 [6–9] (2–15) | 0.229 |

| Total | 7 [5–8]‡ (1–20) | 9 [6–11]‡xƒ (1–27) | 8 [6–10]x (1–19) | 7 [5–9]ƒ (2–20) | <0.001 |

Only these pairs were significant: *(p=0.043), Î(p=0.039), †(p=<0.001), ‡(p=0.013), x(p=0.044) and ƒ(p=<0.001).

The number of samples collected per participant increased between the first two decades (p=0.013). There was a decrease in the number of samples per participant over the subsequent two decades (p=0.044 and p<0.001, respectively). The number of blood samples collected per child increased between the first two decades (p<0.039). Thereafter, it decreased again. The number of blood samples collected per neonate decreased between the second and third decades (p=0.044).

There were no significant differences in volume collected per sample in any of the age groups (table 3).

Table 3.

Blood volume of each sample taken per paediatric patient

| Age group | Volume of blood samples (mL) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976–1985 Median [IQR] (range) |

1986–1995 Median [IQR] (range) |

1996–2005 Median [IQR] (range) |

2006–2015 Median [IQR] (range) |

Statistical analysis (overall p value) | |

| Neonates | 0.3 [0.2–0.5] (0.2–0.5) | 0.2 [0.2–0.8] (0.2–1) | 0.5 [0.2–1] (0.1–2) | 0.3 [0.2–0.6] (0.2–1) | 0.754 |

| Infants | 0.5 | 1 [0.4–2] (0.4–2) | 2 [1–2] (0.2–5) | 2 [0.8–2] (0.1–2.5) | 0.577 |

| Children | 4 [1–9] (0.5–10) | 2 [1.5–3] (0.2–10) | 2 [1–3] (0.1–10) | 2 [1–3] (0.2–7) | 0.599 |

| Adolescents | 7 | 8 [7–9] (7–9) | 1 [0.7–2] (0.7–2) | 2 [1–3] (1–3) | 0.594 |

| Mixed age | 2 [1–3] (1–3) | 1.5 [1–3] (0.5–3) | 2 [1–3] (0.1–7) | 1 [0.6–2] (0.1–5) | 0.594 |

| Total | 1 [0.5–5] (0.2–10) | 2 [1–3] (0.2–10) | 2 [1–3] (0.1–10) | 1.5 [1–2] (0.1–7) | 0.226 |

Considering all age groups, the median volume per sample ranged from 1 mL in the first decade to 2 mL in the second and third decades. Between 0.2 and 0.5 mL was collected from neonates over four decades, with no significant differences observed between decades.

There was significant variation in the total amount of blood collected from each paediatric patient between studies, ranging from 1 to 50 mL in the first decade to 0.6 to 77 mL in the last decade (table 4).

Table 4.

Total blood volume for all samples per paediatric patient

| Age group | Total volume of blood samples (mL) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976–1985 Median [IQR] (range) |

1986–1995 Median [IQR] (range) |

1996–2005 Median [IQR] (range) |

2006–2015 Median [IQR] (range) |

Statistical analysis (overall p value) | |

| Neonates | 2 [1.5–5] (1–5) | 4 [2–8] (2–14) | 2 [1–4] (0.6–7) | 2 [0.9–4] (0.6–7) | 0.241 |

| Infants | 3 | 6 [3–22] (3–41) | 14 [5–30] (1–60) | 10 [5–16] (0.6–16) | 0.546 |

| Children | 20 [14–40] (9–50) | 23 [10–30] (2–55) | 18 [8–22] (1–60) | 14 [6–20] (2–77) | 0.041 |

| Adolescents | 35 | 32 [21–35] (21–35) | 16 [7–18] (7–18) | 8 [8–11] (8–11) | 0.042 |

| Mixed age | 15 [7–27] (7–27) | 13 [11–24] (5–24) | 12 [5–16] (3–24) | 10 [5–17] (0.6–50) | 0.284 |

| Total | 8 [3–22] (1–50) | 14 [6–25] (2–55) | 12 [5–21] (0.6–60) | 10 [5–18] (0.6–77) | 0.213 |

The median total volume collected increased from 8 to 14 mL over the first two decades. It subsequently fell over the next two decades to 10 mL. These differences however were not statistically significant due to the large interindividual variation. When all decades were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test, total volume was statistically significant for children and adolescents (table 4). However, when the decades were individually compared using Dunn's multiple comparison test, the p values were borderline for children and adolescents in the second and fourth decades (p=0.055 for children and p=0.045 for adolescents).

Fifty-six of the studies used the method of population PK. There was a significant difference in the frequency of blood sampling between population PK studies (median 5, IQR (3–7)) and non-population PK studies (median 8, IQR (6–10); p=<0.001).

Twenty-nine studies collected more than 12 samples. The number of these studies per decade ranged from five in 1976–1985 to nine in 1985–1995 and 2006–2015.The largest number of blood samples collected in children was 27, and this study was performed in Canada in 1995 studying alfentanil.14

One study in 2007, of children aged 6–12 years, involved the collection of 77 mL of blood during the course of PK study of methylphenidate. In this Canadian study, 7 mL was taken 11 times over 24 hours.15 According to the EMA guideline, these volumes exceeded the maximum allowable total draw in lighter weighing children (ie, those 20–23 kg), which is 42 mL assuming a blood volume of 70 mL/kg. Similarly, another study in 2006, involving children aged 4–19 years, collected 5 mL of blood 13 times over 24 hours (total 65 mL).16 Although the weights were not given in this study, an average child aged 4 years will weigh ∼16 kg, so representing about 5% of their TBV in 24 hours and exceeding the EMA guidance of 3% of TBV.17

Discussion

This study evaluated the number and volume of blood collected per paediatric patient in PK studies over four decades. The median number of blood samples collected per paediatric patient varied between seven and nine across all decades. More blood samples were collected per paediatric patient in the second decade than any other decade. Comparing the first and last decades, there has surprisingly been no overall change in the number of blood samples collected in paediatric patients. This trend was observed across all age groups except in neonates. Neonates generally had fewer blood samples than any other age group. The population PK studies were associated with fewer blood samples. Greater use of population PK may result in fewer blood samples being collected.

There are currently no guidelines on the frequency of blood sampling in children; hence, a highly varied number of samples are used in paediatric PK studies as shown in this review. The utility of guidelines however depends on the type of PK study. For population PK studies, it has been suggested that no more than six samples need to be collected18 and for neonates, three samples are thought to be optimal for the estimation of PK parameters.19 In this review, the median frequency of blood sampling in neonates was between five and seven. Despite the recommendations for less frequent blood sampling, Reed showed that the greater the number of blood samples taken, the better the estimation of PK parameters.20 This conclusion was reached after comparing PK parameters obtained from 5 to 12 sampling time points.20 This therefore needs to be balanced against the need to limit the number of samples depending on the patient age and disease.

The available guidelines on the volume of blood samples for PK studies in children are highly varied with most recommendations suggesting a range between 1% and 5% of TBV within 24 hours and not more than 10% of TBV within 8 weeks.21 Children's TBV can be estimated from their weight (70 mL/kg), and preterm neonates have ∼90 mL/kg and term neonates 80 mL/kg. This suggests that a 3 kg neonate will have a TBV of about 240 mL. We found the largest TBV drawn from preterm neonates to be 4 mL, in a PK study of cefoperazone.22 The weights of neonates in this study were not reported; hence, it could not be exactly determined whether the maximum allowable TBV draw based on EMA recommendations was exceeded, but it would have represented ∼1.5% of the TBV of a 3 kg term baby.10 In another study of midazolam in term neonates, a sample volume of 0.5 mL was taken on 14 occasions, total volume 7 mL in 24 hours.23 Therefore, each individual sample and total volume did not exceed 1% and 3%, respectively, per EMA guideline for a 3 kg baby.

The maximum recommended allowable blood draw is a percentage of blood volume per body weight. It is often difficult to ascertain whether the studies involving children and adolescents exceeded these recommendations as they may have wide age ranges and only quote a mean or median weight. Two Canadian studies involved the collection of 77 and 65 mL, respectively, over a 24-hour period in children.15 16 The maximum recommended volumes were exceeded in the lightest children recruited in one of these studies.15 The second study of temozolomide, however, did not specify the patient's weight. It is therefore very important to look at the whole age and weight ranges of children taking part in PK studies when deciding the blood volumes to be collected. Protocols may need to have different regimens for different ages/weights if the population studied is wide.

Blood samples were collected mainly from a catheter or venous sampling. Catheter sampling is the most convenient sampling method when repeated blood collection is required and minimises the distress of repeated blood sampling. However, a catheter requires nursing care and monitoring; also, it may not always last for the whole duration of the study.24 25 The other sampling method identified was arterial sampling. Unlike venous sampling, it requires greater expertise and may result in bleeding. Venous sampling is also generally preferred to heel pricks in neonates, because it is less painful and more likely to provide the required volume.26

The dangers of excessive blood sampling include the increased risk of infection, bruising, pain and higher rates of blood transfusion.27 A correlation between the blood volume sampled and transfusion rate has already been shown in neonates.28 A major limitation of this study is that some studies did not report the results for different paediatric age groups. Additionally, some studies were also limited by the lack of data on weight. Therefore, compliance of these studies with guidelines could not be determined. Furthermore, an accurate comparison within paediatric age groups is difficult because of the wide age range in paediatrics. Also, some studies did not provide information on volume. Finally, only one investigator carried out the literature search and data extraction.

In conclusion, definitive evidence-based guidelines should be developed regarding the maximum volume and number of samples that should be collected in children of various ages. There is presently no guideline on frequency of blood sampling, and the guidelines on volume are variable. More attention needs to be given to reducing the number of blood samples and the total volume of blood collected in an individual patient by using microanalytical techniques and population PK methods. Consideration should be given by researchers to all ages/weights of potential children within the study, as to whether the single volume or total volume of blood exceeds current guidance.

Footnotes

Contributors: MIA did the literature search, extracted the data and wrote the manuscript. HS reviewed and validated the extracted data. IC edited the initial draft and subsequent drafts. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Thomson AH. Introduction to clinical Pharmacokinetics. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther 2000;4:3–11. 10.1185/1463009001527660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith M. Taking blood from children causes no more than minimal harm. J Med Ethics 1985;11:127–31. 10.1136/jme.11.3.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodenough B, Kampel L, Champion GD et al. An investigation of the placebo effect and age-related factors in the report of needle pain from venipuncture in children. Pain 1997;72:383–91. 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00062-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith M, Delves T, Lansdown R. The effects of lead exposure on urban children: the Institute of Child Health/Southampton study. Dev Med Child Neurol 1983;47:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saeed MA, Gatens PF. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome: unusual etiologies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1983;64:182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation. WHO guidelines on drawing blood: best practices in phlebotomy. 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel P, Tanna S, Mulla H et al. Dexamethasone quantification in dried blood spot samples using LC–MS: the potential for application to neonatal pharmacokinetic studies. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2010;878:3277–82. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel P, Mulla H, Tanna S,et al. Facilitating pharmacokinetic studies in children: a new use of dried blood spots. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:484–7. 10.1136/adc.2009.177592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO, Wade JR. Nonlinearity detection: advantages of nonlinear mixed-effects modeling. AAPS PharmSci Tech 2000;2:114–23. 10.1208/ps020332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agency EM. Guideline on the Investigation of medicinal products in the term and preterm neonate. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003750.pdf (accessed 5 Apr 2016).

- 11.Categories of research that may be reviewed by the institutional review board (IRB) through an expedited review procedure. US Health and Human Services Office for Human Research Protections. http://www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/RunningClinicalTrials/ucm119074.htm (accessed 5 Apr 2016).

- 12.Kastner M, Wilczynski NL, Walker-Dilks C et al. Age-specific search strategies for Medline. J Med Internet Res 2006;8:e25 10.2196/jmir.8.4.e25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rose K, Stötter H. ICH E 11: Clinical investigation of medicinal products in the paediatric population. Guide to paediatric clinical research. Basel: Karger, 2007:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiset P, Mathers L, Engstrom R et al. Pharmacokinetics of computer-controlled alfentanil administration in children undergoing cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 1995;83:944–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn D, Bode T, Reiz JL et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of multilayer-release methylphenidate and immediate-release methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Pharmacol 2007;47:760–6. 10.1177/0091270007299759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baruchel S, Diezi M, Hargrave D et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of temozolomide using a dose-escalation, metronomic schedule in recurrent paediatric brain tumours. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:2335–42. 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali K, Sammy I, Nunes P. Is the APLS formula used to calculate weight-for-age applicable to a Trinidadian population? BMC Emerg Med 2012;12:9 10.1186/1471-227X-12-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheiner LB, Beal SL. Evaluation of methods for estimating population pharmacokinetic parameters II. Biexponential model and experimental pharmacokinetic data. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1981;9:635–51. 10.1007/BF01061030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long D, Koren G, James A. Ethics of drug studies in infants: how many samples are required for accurate estimation of pharmacokinetic parameters in neonates? J Pediatr 1987;111:918–21. 10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80219-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed MD. Optimal sampling theory: an overview of its application to pharmacokinetic studies in infants and children. Pediatrics 1999;104(Suppl 3):627–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howie SR. Blood sample volumes in child health research: review of safe limits. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:46–53. 10.2471/BLT.10.080010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenfeld WN, Evans HE, Batheja R et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefoperazone in full-term and premature neonates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1983;23:866–9. 10.1128/AAC.23.6.866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahsman MJ, Hanekamp M, Wildschut ED et al. Population pharmacokinetics of midazolam and its metabolites during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in neonates. Clin Pharmacokinet 2010;49:407–19. 10.2165/11319970-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seemann S, Reinhardt A. Blood sample collection from a peripheral catheter system compared with phlebotomy. J Intraven Nurs 2000;23:290–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herr RD, Bossart PJ, Blaylock R et al. Intravenous catheter aspiration for obtaining basic analytes during intravenous infusion. Ann Emerg Med 1990;19:789–92. 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)81705-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogawa S, Ogihara T, Fujiwara E et al. Venepuncture is preferable to heel lance for blood sampling in term neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2005;90:F432–6. 10.1136/adc.2004.069328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy JE, Ward ES. Elevated phenytoin concentration caused by sampling through the drug-administration catheter. Pharmacotherapy 1991;11:348–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obladen M, Sachsenweger M, Stahnke M. Blood sampling in very low birth weight infants receiving different levels of intensive care. Eur J Pediatr 1988;147:399–404. 10.1007/BF00496419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategy for Embase 1974 to 2015

bmjopen-2015-010484supp_table.pdf (6.2KB, pdf)