Abstract

A 40-year-old woman with antiphospholipid syndrome presented with a 5-day history of right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain, radiating posteriorly, associated with fever and vomiting. She was admitted 1-week prior with an upper respiratory infection and erythema multiforme. Clinical assessment revealed sepsis with RUQ tenderness and positive Murphy's sign. Laboratory results showed raised inflammatory markers, along with renal and liver impairment. CT showed bilateral adrenal infarction and inferior vena cava thrombus. The patient was managed for sepsis and started on heparin. Further immunological investigations revealed a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematous, an exacerbation of which culminated in lupus myocarditis. This case illustrates the importance of promptly recognising adrenal insufficiency in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome and the possible causative agents, which require careful consideration and exclusion to prevent further thrombotic events. It also highlights the importance of undertaking imaging, namely CT, in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome presenting with abdominal pain as well as considering concomitant autoimmune conditions.

Background

The patient's initial signs and symptoms presented a picture of cholecystitis. She had deranged liver and renal function tests, persistent hypotension and hypoglycaemia requiring fluid resuscitation. A CT abdomen confirmed adrenal infarction, and the true nature of her presentation, adrenal crisis, became apparent. Her symptoms evolved during her hospital stay, resulting in Intensive Therapy Unit (ITU) admission, and a new diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematous (SLE). This case highlights the difficulty in recognising adrenal crisis, with the non-specific nature of the presentation; the complexity of its presentation in individuals with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and concomitant autoimmune conditions; and the value of undertaking a CT scan in all patients with APS presenting with abdominal pain.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old woman presented to Accident and Emergency (A&E) in a District General Hospital (DGH) with a 5-day history of right, upper quadrant abdominal pain, radiating to the back, associated with fever and vomiting. She described a sudden onset, with no exacerbating or alleviating factors and no other associated symptoms.

She had previously attended A&E 2 days prior to this, with similar symptoms, before being discharged after blood investigations showed no obvious abnormality and an ultrasound scan of the abdomen revealed a mildly distended common bile duct (7.5 mm) and gall bladder sludge. Inspection of her hospital records revealed a recent admission 1-week ago with an upper respiratory tract infection and erythema multiforme, for which she received a course of antibiotics.

Her medical history included Sjorgen's syndrome and recurrent deep vein thrombosis (DVT), secondary to APS. She was previously prescribed lifelong warfarin; however, due to attempts to conceive and multiple miscarriages, she was switched to low molecular weight heparin, which she had taken daily for the last 4 months prior to presentation. However, her compliance with anticoagulation therapy prior to hospital admission was questionable.

Examination in A&E revealed a tachycardia (100 bpm), hypotension (96/54) and fever (39°C). Abdomen was soft, with right upper quadrant (RUQ) tenderness on palpation and positive Murphy's sign, but no indication of peritonism. No renal angle tenderness was documented and the remaining system examinations were normal.

Investigations

Bedside investigations included a urine dip that was positive for ketones (4+) and blood (2+). Capillary blood glucose was documented at 3.7. An arterial blood gas taken on admission shows a pH of 7.39 and lactate of 0.4 mmol/L, with no signs of hypoxia (pO2 11.5).

Blood tests confirmed hypoglycaemia with low serum glucose (2.7 mmol/L). Low platelets (103×109/L) were also observed along with raised inflammatory markers (white cell count 10.4×109/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 93 mm/hour, C reactive protein (CRP) 297 mg/L; CRP previously 7 mg/L 2 days ago when she presented to A&E with similar symptoms). Renal function revealed an increased creatinine (98 µmol/L) in context of normal urea (4.5 mmol/L), with estimated glomerular filtration of 57 (baseline >90). Electrolyte abnormalities were noted, with hyponatraemia (125 mmol/L) and hypokalaemia (3.4 mmol/L) being observed. Liver profile showed derangement in alkaline phosphatase (192 iU/L) and albumin (33 g/L), but was otherwise normal. Amylase was within normal limits (75 iU/L).

Blood and urine cultures were undertaken on admission; however, no growth was observed in either samples. With respect to imaging, chest X-ray was unremarkable. As an ultrasound abdomen had been performed 2 days prior, a CT abdomen/pelvis was undertaken in order to identify any possible further pathology. This showed a small thrombus located in the suprarenal inferior vena cava (figure 1) along with bilateral adrenal devascularisation and swelling suggestive of non-haemorrhagic venous infarction (figure 2), with small pleural effusions.

Figure 1.

CT scan, frontal section, showing small suprarenal IVC thrombus. IVC, inferior vena cava.

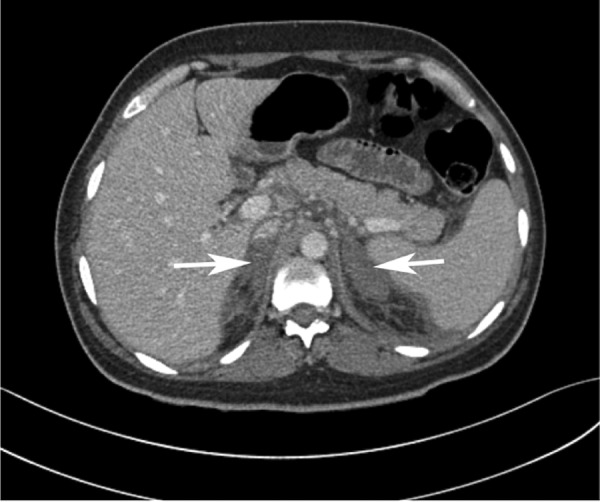

Figure 2.

CT scan, horizontal section, showing bilateral adrenal infarction with no visible haemorrhage.

The risk of adrenal crisis was immediately raised. Subsequent investigations showed serum cortisol <3 mmol/L and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) 84.5 ng/L (a recent ACTH result was normal at 22.8 ng/L).

Differential diagnosis

Fever and RUQ pain with raised inflammatory markers suggested an underlying sepsis, possibly of biliary origin. However, the CT abdomen showing likely adrenal venous infarction and inferior vena cava thrombosis, with no other abnormalities, negated this as a possible cause. The hyponatraemia, hypoglycaemia and hypotension can all be explained by the adrenal insufficiency (AI) resulting from the necrosis. Low potassium, however, is less explainable, perhaps a result of increased vomiting. The elevation in ACTH and lack of buccal pigmentation provide evidence of an acute presentation of AI.

The most likely cause of adrenal infarction in this case is bilateral adrenal vein thrombosis secondary to APS. The question is what precipitated this? Possible causes included:

Sepsis.

Non-compliance with medication or incorrect dosing.

Treatment

Immediate management included treatment of suspected sepsis following national guidelines, starting empirical antibiotics, intravenous fluids and electrolyte replacement for derangements. A catheter was also placed to monitor urine output.

Once adrenal infarction with AI had been diagnosed, she was started on high-dose intravenous hydrocortisone (200 mg), followed by successive doses every 6 hours. This continued for a 24-hour period before switching to oral hydrocortisone along with intravenous pantoprazole 40 mg 12 hourly.

Anticoagulation was started in light of the thrombi on CT. With a low platelet count, this needed to be carried out with care, especially with the consideration that it may have been due to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). HIT was, however, seen to be an unlikely cause due to a low HIT score (3), combined with the fact she had been on heparin since January with no significant drop in platelets. Unfractionated heparin was started, with close monitoring of platelets and clotting factors.

Outcome and follow-up

There was a question as to whether or not the patient had poor compliance with her tinzaparin, having refused warfarin previously due to wanting to conceive. The patient was placed on unfractionated heparin in order to prevent further clot formation. Unfortunately, her platelet count continued to drop, the lowest being 44×109/L, but recovered even while heparin treatment continued. Her HIT screen was weakly positive for PF4–heparin antibodies (Abs) (0.950 ELISA Optical Density); however, HIT was excluded as she had low clinical suspicion in combination with a low–moderate titre of her antigen assay.1 Long-term anticoagulation is the recommended management for patients with APS with unprovoked venous thrombosis events, with warfarin historically being the safest treatment.2 She decided to resume warfarin therapy in light of her three previous miscarriages, risk of DVTs and HIT, understanding that further pregnancies would not be advised while on this treatment.

Throughout her admission, the patient was persistently febrile with elevated inflammatory markers, despite no obvious source of infection and escalation of antibiotics to intravenous piperacillin/taobactam and meropenem. A repeat CT chest/abdomen/pelvis was undertaken which showed no change in adrenal glands or pleural effusions. She subsequently developed left-sided pleuritic pain accompanied with a sinus tachycardia (105/min), tachypnoea (24/min) and hypoxia (9.0 kPa on 28% oxygen). Further investigation showed a troponin of 1242 ng/mL. A transthoracic echocardiogram was undertaken, showing an ejection fraction of 20% with severely impaired left ventricular function and normal right ventricle. In light of these findings, she underwent a coronary angiography, which showed normal coronary vessels. With no obvious cause identified for either the persistent or acute symptoms, further autoimmune investigations were undertaken.

Analysis of the patient's previous autoimmune profile revealed APS with lupus anticoagulant (LAC) antibody positivity. It was also uncovered that while anti-dsDNA negative, she was anti-Sm positive. On questioning, the patient reported a history of lethargy, depression, as well as intermittent and multiple joint pains. She also had objectively tender multiple proximal interphalangeal joints on examination. Her recent admission with an erythema multiforme-like rash could have been a cutaneous manifestation of SLE. In light of these symptoms, a diagnosis of SLE was made using the SLICC criteria (table 1). Her symptoms were subsequently attributed to a SLE ‘flare’ causing myocarditis. She was started on intravenous methylprednisolone, hydoxychloroquinine and intravenousIg.

Table 1.

Clinical and immunological criteria in SLICC classification criteria3

| Present | |

|---|---|

| Clinical criteria | |

| Acute cutaneous lupus | ? ✓ |

| Chronic cutaneous lupus (including classical discoid rash) | |

| Oral ulcers | |

| Nonscarring alopecia | |

| Synovitis involving 2+ joints | ✓ |

| Serositis | ✓ |

| Renal | |

| Neurological | |

| Haemolytic anaemia | |

| Leucopenia or lymphopenia | ✓ |

| Thrombocytopenia | ✓ |

| Immunological criteria | |

| ANA | ✓ |

| Anti-dsDNA | |

| Anti-Sm | ✓ |

| Antiphospholipid antibody | ✓ |

| Low complement | |

| Direct coombs | ✓ |

Four or more clinical and immunological required with at least one clinical and one immunological or biopsy confirmed nephritis compatible with lupus (ANA or anti-dsDNA antibodies).

She required an ITU admission due to persistent hypotension (systolic blood pressure 78) after the angiography and was referred from the DGH to a specialist centre after a 3-week admission due to the complexities of managing APS and SLE in this case. She was subsequently discharged with lifelong steroid replacement therapy and warfarin with a target international normalised ratio (INR) of 3–4. She was followed-up as an outpatient with cardiology, endocrinology, rheumatology and haematology involvement.

Discussion

APS is a prothrombotic autoimmune disorder characterised by medium-to-large vessel thrombosis and/or pregnancy complications. As APS can affect veins and arteries, as well as virtually any organ in the body, it has a variety of clinical features. AI is an infrequent complication of APS; however, it may also be the first clinical presentation of the syndrome.4

The clinical presentation of AI in this patient is fairly typical of the reported cases of haemorrhagic infarction of the adrenals due to APS, with abdominal pain shown to be the commonest symptom, occurring in 55% of cases. Other presentations include: hypotension (54%), fever (40%), nausea or vomiting (31%), weakness/fatigue (31%) and altered mental state (19%).4 The patient in this case presented with pain localised specifically to the RUQ. Although there are some cases of RUQ pain in adrenal insults, there are no reported cases of RUQ pain as a presenting feature with APS.5 Nonetheless, it is important to have a high level of clinical suspicion of AI in any patient with a background of APS who presents with abdominal pain. Alongside blood tests such as a random cortisol, or short synacthen test, imaging such as a CT abdomen should also be undertaken.

With laboratory findings, Espinosa et al reviewed all reported cases of primary AI associated with APS between 1983 and 2002. They found that hyponatraemia and/or hyperkalaemia were the commonest laboratory abnormalities, with only 2 of 86 cases reporting hypoglycaemia.4 While our patient presented with hypoglycaemia, they also presented with hypokalaemia, not hyperkalaemia, which is commonly shown in other cases of AI. This further supports the necessity of maintaining a high level of suspicion of AI in patients with APS who do not necessarily conform to biochemical investigation.

When considering the underlying mechanism that resulted in adrenal necrosis, there are multiple causes that could underlie our patient's presentation. While the exact pathogenesis of adrenal infarction is not known in APS, it has been hypothesised that the hypercoaguable state leads to adrenal vein thrombosis, which results in haemorrhagic infarction of the adrenal gland. Unlike other previously reported cases, however, infarction in this instance did not result in haemorrhage. Nonetheless, the infarctions are often bilateral, and thought to localise to this area partly due to the unique and peculiar anatomical structure of the adrenal vasculature. This comprises a rich arterial supply with a single vein limiting blood drainage which, when thrombosed, can result in progressive increase in arterial blood pressure.6 There is a predisposition to intraglandular haemorrhage due to an intrinsically vulnerable network; this results from a ‘vascular dam’ that is created from the sharp transition from the artery to capillary system around the zona reticularis.7 In certain circumstances, adrenal infarction can be due to local stasis of blood rather than thrombosis. In Waterhouse-Friederichsen syndrome (WFS), for example, sepsis causes a stress response that results in an increase in ACTH. This in turn increases arterial blood flow exceeding the limited venous drainage.

While WFS is often triggered by bacterial sepsis, viral infections are a common precipitating factor for thrombosis resulting in AI with APS.4 Possible reasons for the resultant thrombosis include the fact that repeated infections have been shown to increase the level of antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies, with viral infections more frequently causing thrombus than bacterial.8

Immunological investigation revealed our patient to be LAC positive, a type of aPL antibody that shows the closest association with thrombus formation.8 In the presence of LAC antibody, thrombosis can occur spontaneously, or be precipitated by insults such as infection.2 Blood cultures were, however, negative and no identifiable source of infection was identified.

Lack of compliance with anticoagulation medication can allow for thrombus formation. Long-term anticoagulation is the recommended management for patients with APS with unprovoked venous thrombosis events, with warfarin historically being the safest treatment in non-pregnant women.2 The patient was started on anticoagulation therapy due to recurrent DVTs; possible compliance issues in combination with the high-risk LAC antibody may have caused the thrombosis resulting in her initial presentation.

In regards to the patient's persisting features throughout her hospital stay, there was a question as to whether another autoimmune condition may have been a factor. The patient was subsequently found to be SLE positive, a differential that was not considered on her initial presentation. SLE is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterised by multisystem, microvascular inflammation. It has many non-specific clinical features and can have a variety of different presentations. SLE has a relapsing and remitting course, and exacerbations (or ‘flares’) can also be triggered by infections. SLE commonly coexists with APS, in which the syndrome is then termed ‘secondary’; however, SLE is itself a risk factor for thrombosis.

Although reports mention bilateral adrenal haemorrhage in patients with comorbid SLE and APS, the literature does not attribute this solely to SLE.4 SLE also causes thrombocytopenia and could explain the patients’ persistent abdominal pain, fever and the cardiac features. The heart is frequently involved in SLE, with all three layers (pericardium, myocardium and endocardium) affected.9 Although lupus myocarditis is uncommon, it would explain the symptoms she later suffered, with the accompanied rise in troponin and hypokinesia on echocardiography, in light of a normal angiography. Endomyocardial biopsy can give a definitive diagnosis but has limited sensitivity and specificity.10 It is more than likely that her persisting symptoms throughout admission were the result of an SLE ‘flare’, with complete resolution upon commencement of aggressive SLE treatment.

Overall, this case highlights the difficulty faced by clinicians in diagnosing AI, especially in the context of APS. While uncommon, adrenal infarction can occur and the numerous possible causative agents need careful consideration and exclusion to ensure prevention of further thrombotic events or exacerbations. There was either concurrent activation of APS and SLE or the AI may have been solely due to SLE. Both possible cases are not widely represented in the literature. Also not previously reported is adrenal infarction without haemorrhage. While those with adrenal infarction can often recover adrenal function, in this case, it is unlikely. Successive CT has shown no change in the adrenal glands and the thrombotic infarction is likely to have caused permanent necrosis. With such a short time frame between presentations, this case also highlights the importance of biochemically investigating for AI and considering further imaging, namely CT, in any patient with a background history of APS presenting with abdominal pain.

Learning points.

The presentation of adrenal infarction in antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and sepsis can often mimic one another.

Imaging, such as CT abdomen, should be considered in all patients presenting with abdominal pain and a background of APS.

While not traditionally reported, adrenal infarction can occur without haemorrhage in patients with APS, as this case highlights.

Prompt recognition, appropriate management and steroid replacement, along with multidisciplinary team involvement, are crucial in managing patients with adrenal insufficiency.

Concomitant autoimmune conditions must be considered in anyone with APS, particularly in those with persisting symptoms refractory to conventional treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Mr Kaiyumars Contractor, Dr Sanjeev Mehta and Dr Mamta Sohal for their expert opinion and advice in managing the patient during her hospital stay.

Footnotes

Contributors: HS headed up the case report. NMB helped manage the patient during her initial presentation. MH diagnosed adrenal infarction and provided senior support. DM summarised the patient's notes and wrote the manuscript with the help of NMB. NMB monitored patient follow-up. DM analysed and revised the paper. HS provided senior support and review of the paper with DM.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Raschke RA, Curry SC, Warkentin TE et al. . Improving clinical interpretation of the anti-platelet factor 4/heparin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia through the use of receiver operating characteristic analysis, stratum-specific likelihood ratios, and Bayes theorem. Chest 2013;144:1269–75. 10.1378/chest.12-2712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keeling D, Mackie I, Moore GW et al. . Guidelines on the investigation and management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol 2012;157:47–58. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarćon GS et al. . Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2677–86. 10.1002/art.34473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espinosa G, Santos E, Cervera R, et al.. Adrenal involvement in the antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic characteristics of 86 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:106–18. 10.1097/00005792-200303000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdullah KG, Stitzlein RN, Tallman TA. Isolated adrenal hematoma presenting as acute right upper quadrant pain. J Emerg Med 2012;43:215–17. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox B. Venous infarction of the adrenal glands. J Pathol 1976;119:65–89. 10.1002/path.1711190202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Presotto F, Fornasini F, Betterle C, et al.. Acute adrenal failure as the heralding symptom of primary antiphospholipid syndrome: report of a case review of the literature. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;153:507–14. 10.1530/eje.1.02002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cervera R, Asherson RA, Acevedo ML, et al.. Antiphospholipid syndrome associated with infections: clinical and microbiological characteristics of 100 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1312–17. 10.1136/ard.2003.014175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tincani A, Rebaioli CB, Taglietti M, et al.. Heart involvement in systemic lupus erythematous, anti-phospholipid syndrome and neonatal lupus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(Suppl 4):8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman A, McNamara D. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1368–98. 10.1056/NEJM200011093431908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]