Abstract

Objectives

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a well-established risk factor for many health outcomes. Recently, we developed an SES measure based on 4 housing-related characteristics (termed HOUSES) and demonstrated its ability to assess health disparities. In this study, we aimed to evaluate whether fewer housing-related characteristics could be used to provide a similar representation of SES.

Study setting and participants

We performed a cross-sectional study using parents/guardians of children aged 1–17 years from 2 US Midwestern counties (n=728 in Olmsted County, Minnesota, and n=701 in Jackson County, Missouri).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

For each participant, housing-related characteristics used in the formulation of HOUSES (assessed housing value, square footage, number of bedrooms and number of bathrooms) were obtained from the local government assessor's offices, and additional SES measures and health outcomes with known associations to SES (obesity, low birth weight and smoking exposure) were collected from a telephone survey. Housing characteristics with the greatest contribution for predicting the health outcomes were added to formulate a modified HOUSES index.

Results

Among the 4 housing characteristics used in the original HOUSES, the strongest contributions for predicting health outcomes were observed from assessed housing value and square footage (combined contribution ranged between 89% and 96%). Based on this observation, these 2 were used to calculate a modified HOUSES index. Correlation between modified HOUSES and other SES measures was comparable to the original HOUSES for both locations. Consistent with the original HOUSES formula, the strongest association with modified HOUSES was observed with smoking exposure (OR=0.24 with 95% CI 0.11 to 0.49 for comparing participants in highest HOUSES vs lowest group; overall p<0.001).

Conclusions

The modified HOUSES requires only 2 readily available housing characteristics thereby improving the feasibility of using this index as a proxy for SES in multiple communities, especially in the US Midwestern region.

Keywords: socioeconomic status, HOUSES, health disparity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Robust performance of the modified HOUSES demonstrates its application to different geographic regions with minimal property data.

The modified HOUSES index does not rely on the quality of imputation of missing housing characteristics.

This study is limited by self-reported health outcomes.

The study is limited by testing the modified index in only two locations.

This study may not work well in other countries where housing data are not routinely collected or not made publically available.

Introduction

The impact of socioeconomic status (SES) on health outcomes has been well documented in the USA and elsewhere and included in assessments of frameworks for health disparities.1–6 Overall, these frameworks for health disparities suggest that distal factors such as individual SES impact human health independently, jointly and interactively with proximal factors (eg, genetic predisposition or biological responses). Thus, SES, its definition and method of calculation can have important consequences on clinical practice, research and health policy concerning health disparities.

SES reflects multifaceted assets or capacities of humans including materialistic, human and social capital, making accurate measurement of SES a potentially formidable task. One of the biggest challenges in health disparities research is the complexity of reporting individual's SES using commonly available data such as information found in medical records and administrative databases. To address this important gap in the ability to operationalise SES using data available to healthcare researchers, our research group developed an individual housing-based SES measure termed HOUSES.7 8 HOUSES is a composite index consisting of assessed housing value, square footage and the numbers of bedrooms and bathrooms available from property data found in the assessor's office of the county government. Using address information documented in medical records or administrative data sets linked to the county assessor's data, we were able to calculate an effective SES proxy without the need for specific educational or income levels, which are rarely available in the medical record or administrative data. The HOUSES index predicts health outcomes in adults and children that have previously been identified to be associated with SES (low birth weight, obesity, smoking exposure, asthma control status, pneumococcal diseases, postmyocardial infarction mortality, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and post-RA mortality).7–13

One of the challenges in calculating the original HOUSES index is the need for complex assessor's real property data generated for US taxation purposes. However, these data often does not include key variables of interest such as the number of bedrooms and bathrooms. For example, the 2013 real property data of Olmsted County, Minnesota (MN), have 3–6% missing data on the number of bedrooms and bathrooms of single family housing units while assessed housing value and square footage is almost complete (<1% missing data). The rates of missing information on the number of bedrooms and bathrooms tend to vary depending on the age of the real property data and/or geographic regions of interest.

To address this concern, we explored whether the original HOUSES index could be modified using fewer housing-related characteristics, especially assessed housing value and square footage as these two components are consistently available in most counties and state property databases. Our aim was to evaluate whether a modified HOUSES index would provide an equivalent representation of SES to the original HOUSES index.

Methods

Study participants and design

The original study enrolled parents/guardians of children aged 1–17 years living in Olmsted County, MN (n=746) or Jackson County, Missouri (MO; n=704) in 2006. The present study included those who had both successful geocoding of address with real property data and formulation of HOUSES index (728 participants for Olmsted County, MN, and 701 participants for Jackson County, MO). Detailed description of the study population and methodology for developing and validating the HOUSES index were previously reported by Juhn et al.8 Briefly, participants were originally recruited for the HOUSES derivation and validation study.8 Data collection included sociodemographic characteristics and health-related information obtained through a telephone survey given to the one parent or guardian who answered the phone. This information was then linked to the property data associated with each participant's address. Property data were acquired from the county assessor's offices. For comparison, additional SES measures were included in the survey questionnaire, to describe parental education level (ie, the highest educational level of either parent), family annual income, Hollingshead index (a family's composite index using education, occupation, sex and marital status) and Nakao-Treas index (composite index using educational attainment and income of job incumbents corresponding to the 1980 census).14–16

For formulating the HOUSES index, principal component factor analysis was performed using seven housing-related features obtained in the real property data, including (1) square footage of housing unit, (2) assessed housing value, (3) number of bathrooms, (4) number of bedrooms, (5) ownership of housing unit, (6) residential status (whether a housing unit is in a residential zone) and (7) lot size of housing unit in acres, and six neighbourhood characteristics collected from census tract-level data, including (1) per cent of people speaking English as a second language, (2) per cent of foreign-born people, (3) per cent of households headed by a female, (4) per cent of households that are non-family households, (5) per cent of people with less than a high school education and (6) per cent of families with family income below poverty level. The original HOUSES index was calculated using four housing-related characteristics (assessed housing value, square footage, number of bedrooms and number of bathrooms) included in the first factor, accounting for the largest proportion of total variance. These four housing components were transformed to standardised z-scores, and then summed to formulate the HOUSES index. In the original study, it was demonstrated that a higher four-item HOUSES score was related to a higher level of SES using other SES measures and also inversely associated with outcome measures assessed among participants from both counties. While the HOUSES index developed in Olmsted County, MN, and was validated in Jackson County, MO, in the original study, this index was further validated to a different tax jurisdiction and real property data system in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.12 Correlation of HOUSES with the health-related outcomes of childhood obesity, low birth weight and smoking were evaluated because the association between these outcomes and SES has been well demonstrated.17–19

To assess whether fewer housing-related characteristics could be used, the relative influence (RI) of each characteristic for predicting the health outcomes (obesity, low birth weight and smoking exposure) was estimated using gradient boosting machine (GBM) models under logistic regression model frameworks. The GBM modelling approach is a machine learning technique for building a multivariable prediction model by incorporating all of the variables without variable selection.20–22 RI is a measure of a given variable's importance, relative to that of other variables, in the model prediction process. The measure is based on the number of times a variable is selected for splitting in a decision tree, weighted by the improvement of the model fitting as a result of the split and further standardised, so that the sum of RI from all variables adds up to 100%. The higher the RI value (maximum of 100%) of a characteristic, the more significant its contribution is to the model. Those with the greatest contribution were summed to formulate a modified HOUSES index for each county.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to represent sociodemographic characteristics and health-related outcomes for participants for each county. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for correlations between original HOUSES and the modified HOUSES indices. For further analysis, both original HOUSES and modified HOUSES scores were collapsed into four groups using quartiles (Q1 (lowest)–Q4 (highest)). For each HOUSES index, Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for correlations with other SES measures (parental education, family annual income, Hollingshead index and Nakao-Treas index). To evaluate whether the two non-independent correlation coefficients (original and modified HOUSES indices calculated on the same participants) were similar, a t-test based on Hotelling's test accounting for dependency between two HOUSES indices was used.22 In addition, logistic regression models were used to assess the association of the modified HOUSES with risk for health-related outcomes (obesity (body mass index at or above the 95th centile for children of the same age and gender; yes vs no), low birth weight (<2500 g at birth; yes vs no) and smoking exposure (tobacco smoking status of household member; yes vs no)), using Q1 as a reference category. We used the 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) questions to obtain these dependent variables (‘What was child's birth weight?’, ‘How much does child weight now?’, ‘How tall is child now?’ and ‘Does anyone in the household use cigarettes, cigars or pipe tobacco?’).

Results

Characteristics of participants

The results are summarised in table 1. A total of 728 children from Olmsted County, MN, and 701 children from Jackson, MO, were included in the study analysis. The median age of children included in the study was 10 years (25–75th centile: 5–14) with roughly 50% females in both counties (table 1). Residents of Olmsted County, MN, were more likely to have higher levels of education and income than residents of Jackson County, MO. Obesity rates (15% vs 12%) and smoking exposure (27% vs 12%) were higher in Jackson County, while the rate of low birth weight was higher in Olmsted County (11% vs 6.5%). The median HOUSES index was −0.44 (25–75th centile: −1.11 to 0.91) in Olmsted County, MN, and −0.46 (−1.22 to 0.88) in Jackson County, MO.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and health outcomes of the study participants

| Olmsted County, MN (n=728) | Jackson County, MO (n=701) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age (years), median (25–75th centiles) | 10 (5–14) | 10 (5–14) |

| Sex, female N (%) | 358 (49%) | 355 (51%) |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | ||

| Parents' education | ||

| Less than high school education | 4 (0.5%) | 18 (2.6%) |

| High school graduate | 37 (5.1%) | 103 (15%) |

| Some college, no degree | 140 (19%) | 173 (25%) |

| Associate/college degree | 291 (40%) | 229 (33%) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 256 (35%) | 178 (25%) |

| Family annual income | ||

| <$24 999 | 9 (1.3%) | 51 (7.8%) |

| $25 000–$49 999 | 86 (12%) | 139 (21%) |

| $50 000–$74 999 | 144 (20%) | 154 (24%) |

| $75 000–$99 999 | 161 (22%) | 136 (21%) |

| Over $100 000 | 316 (44%) | 175 (27%) |

| Hollingshead index | ||

| 8–19 | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (0.3%) |

| 20–29 | 12 (1.6%) | 35 (5.0%) |

| 30–39 | 54 (7.4%) | 109 (16%) |

| 40–54 | 254 (35%) | 268 (38%) |

| 55–66 | 406 (56%) | 287 (41%) |

| Nakao-Treas index | ||

| 0–12.5 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 12.6–25.1 | 2 (0.3%) | 5 (0.7%) |

| 25.2–37.7 | 53 (7.3%) | 101 (14%) |

| 37.8–50.3 | 79 (11%) | 105 (15%) |

| 50.4–62.9 | 109 (15%) | 105 (15%) |

| 63.0–75.5 | 184 (25%) | 192 (27%) |

| 75.6–88.1 | 230 (32%) | 156 (22%) |

| 88.2–100 | 71 (9.8%) | 37 (5.3%) |

| Health outcomes | ||

| Obesity, N (%) | 71 (12%) | 81 (15%) |

| Low birth weight, N (%) | 78 (11%) | 43 (6.5%) |

| Smoking exposure, N (%) | 89 (12%) | 188 (27%) |

MN, Minnesota; MO, Missouri.

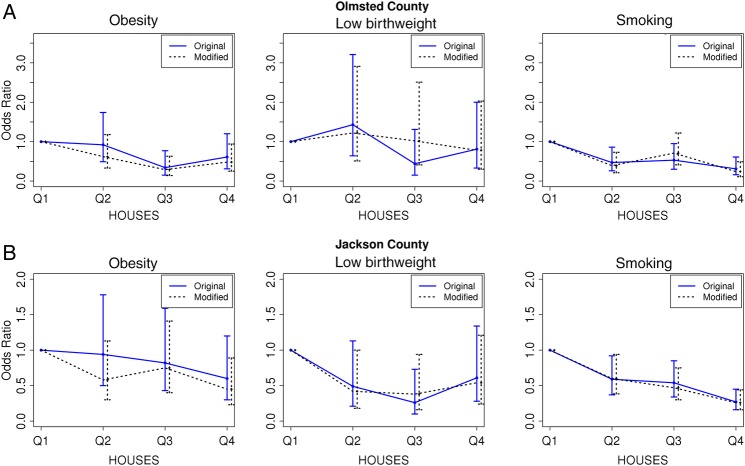

Identification of housing characteristics with most significant contributions for health outcomes

The results are summarised in figure 1A (for Olmsted County) and figure1B (for Jackson County). Simultaneously considering all four housing characteristics used in the original HOUSES formula, assessed housing value and square footage had the greatest contribution to all three health outcomes in both counties (figure 1A, B). The combined contribution of assessed housing value and square footage ranged between 89% and 96% depending on health outcome evaluated. The contribution of number of bedrooms and bathrooms is negligible in the presence of assessed housing value and square footage (<10% for all three outcomes). Therefore, assessed housing value and square footage were transformed to standard z-scores and then summed to formulate a modified HOUSES index.

Figure 1.

Relative influence (per cent) of four housing features (assessed housing value, square footage, number of bedrooms and number of bathrooms) for risk of obesity, low birth weight and smoking exposure among participants from Olmsted County (panel A) and Jackson County (panel B).

The modified HOUSES index for presenting SES

The results are summarised in tables 2 and 3 and figure 2. The modified HOUSES index was highly correlated with original HOUSES based on four housing components (0.87 in Olmsted County, and 0.93 in Jackson County). Correlations between the modified HOUSES index with other SES measures were comparable or slightly higher to the original HOUSES index for both counties (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the correlation coefficients of two HOUSES indices with other SES measures

| Olmsted County, MN |

Jackson County, MO |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original HOUSES | Modified HOUSES | p Values* | Original HOUSES | Modified HOUSES | p Values* | |

| Parents’ education | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.07 |

| Family annual income | 0.43 | 0.49 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.06 |

| Hollingshead index | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.24 |

| Nakao-Treas index | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.56 |

*Each p value represents statistical significance for the difference between the two Spearman correlation coefficients (r1 and r2): (r1: the correlation coefficient between the original HOUSES index and each individual SES measure) and (r2: the correlation coefficient between the modified HOUSES index and each individual SES measure). Lack of statistical significant difference (p>0.05) means no difference between r1 and r2.

MN, Minnesota; MO, Missouri; SES, socioeconomic status.

Table 3.

Associations (unadjusted OR and 95% CI) between modified HOUSES and risk of childhood obesity, low birth weight and smoking exposure

| Obesity, OR (95% CI) | Low birth weight, OR (95% CI) | Smoking exposure, OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olmsted County | (overall p=0.01) | (overall p=0.82) | (overall p<0.001) |

| Q1 (lowest SES) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Q2 | 0.62 (0.33 to 1.18) | 1.22 (0.51 to 2.91) | 0.39 (0.21 to 0.73)** |

| Q3 | 0.29 (0.14 to 0.63)** | 1.02 (0.41 to 2.51) | 0.71 (0.41 to 1.22) |

| Q4 (highest SES) | 0.48 (0.25 to 0.94)* | 0.78 (0.30 to 2.03) | 0.24 (0.11 to 0.49)** |

| Jackson County | (overall p=0.11) | (overall p=0.08) | (overall p<0.001) |

| Q1 (lowest SES) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Q2 | 0.58 (0.30 to 1.13) | 0.42 (0.18 to 1.00)* | 0.60 (0.38 to 0.94)* |

| Q3 | 0.75 (0.40 to 1.41) | 0.38 (0.16 to 0.94)* | 0.47 (0.30 to 0.75)** |

| Q4 (highest SES) | 0.45 (0.23 to 0.89)* | 0.54 (0.34 to 1.21) | 0.26 (0.16 to 0.44)** |

*p<0.05.

**p<0.01.

SES, socioeconomic status.

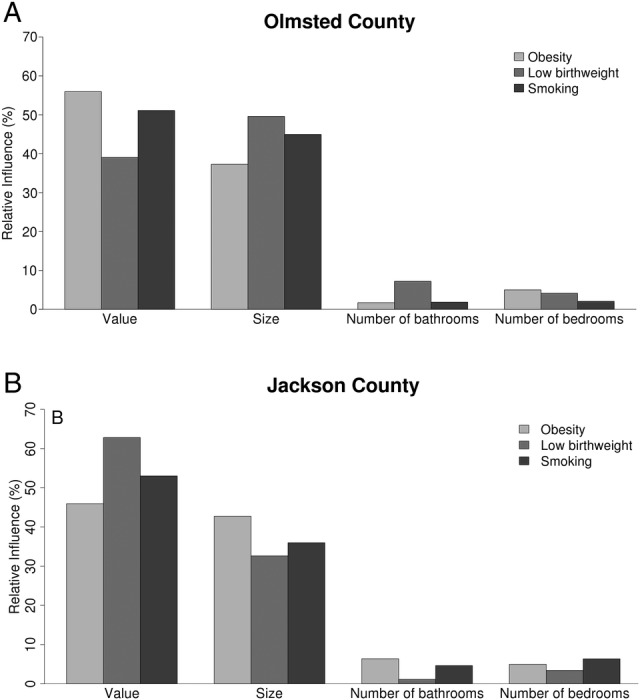

Figure 2.

Association comparisons between modified HOUSES (OR and 95% CIs with dotted line) and original HOUSES (OR and 95% CIs with solid line) for three health-related outcomes (obesity, low birth weight and smoking exposure) among participants from Olmsted County (panel A) and Jackson County (panel B).

Overall, the modified index performs similar to the original HOUSES index in inverse associations with health outcomes (table 3 and figure 2). Figure 2 depicted ORs and their 95% CIs for association between the modified HOUSES (using Q1 as a reference group) and each of three health outcomes (panel A for Olmsted County and panel B for Jackson County). In addition, figure 2 includes the association results with the original HOUSES for comparison. The 95% CIs for the modified HOUSES were overlapped with those for the original HOUSES for all three outcomes and both counties, which implied that the association results between two HOUSES measures were similar. The strongest health-related outcome association with the modified HOUSES Index was observed for smoking exposure (OR 0.24 with 95% CI 0.11 to 0.49 in Olmsted County and OR 0.26 with 95% CI 0.16 to 0.44 in Jackson County, comparing participants in highest (Q4) vs lowest (Q1) group; overall p<0.001 for both locations). The risk of childhood obesity was also inversely associated with the modified HOUSES, although not statistically significant in Jackson County (overall p=0.01 in Olmsted County; p=0.11 in Jackson County). The association for the risk of low birth weight was inconsistent between two counties (table 3). We postulate that the lack of significant association in Olmsted County might be partly due to unique characteristics of the Olmsted County population, such as a relatively high prevalence of recent Somali immigrants with low SES. As mentioned in the original paper describing the HOUSES index, the incidence of low birth weight in Somali population was lower than the US average.8 In addition, a high incidence of multiple gestations (associated with low birth weight) from in vitro fertilisation participants among a relatively higher SES group in Olmsted County might also contribute to the results.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the utility of the ‘modified’ HOUSES index as a suitable tool for health disparities research. The modified HOUSES relies on only two housing-related variables (assessed housing value and square footage), data usually publicly available. We made four main observations, providing reliability, validity, predictability and generalisability of the modified HOUSES index as an alternative SES measure. First, the modified HOUSES was strongly correlated with the original four component HOUSES (assessed housing value, square footage, number of bedrooms and bathrooms) index in both counties evaluated and the correlation coefficients between two HOUSES indices was similar in both counties (ie, reliability across different geographic settings). Second, the correlation coefficients between the modified HOUSES index with other SES measures (eg, parental education) were comparable to the original HOUSES index for both counties (ie, validity). Third, the associations of this modified HOUSES index with health outcomes or related known risk factors linked to SES, such as smoking exposure, were consistent with those of the original HOUSES (ie, predictability). Finally, the modified HOUSES index used two housing features commonly captured in real property data throughout diverse communities within the USA, and provided consistent results in the two geographically different regions (ie, generalisability).

The observed relatively minimal influence of not including bedroom and bathroom count in the modified HOUSES has several potential explanations. First, the variances of assessed housing values and square footage, continuous variables, are larger than those for number of bedrooms and bathrooms, discrete variables with smaller ranges. Therefore, it is possible that the impact of bedroom and bathroom counts may be minimal once assessed housing value and square footage are considered. Second, as missing information for bedroom and bathroom count were imputed with the mean value in the original HOUSES index, their impact (variance) might have been reduced, compared with assessed housing value and square footage, for which there were few missing values. Finally, while positive correlations exist among number of bedrooms, square footage, number of bathrooms and assessed housing value, we found that assessed housing value and square footage better correlate with other SES measures than the number of bedrooms and bathrooms. For example, assessed housing value (r=0.52) and square footage (r=0.48) are more closely correlated with income, compared with the self-reported number of bedrooms (r=0.18) and bathrooms (r=0.37). Thus, the number of bedrooms and bathrooms conceptually seems to only add a finer granularity in capturing housing-based SES. Therefore, based on these conceptual and methodological aspects of the housing features, the modified HOUSES index performed as well as the original HOUSES index.

The paucity of readily accessible SES-related data is a common but major challenge for existing large-scale data sets (eg, disease registry, administrative data sets) rendering them less valuable for conducting health disparities research. Therefore, use of housing-based SES (ie, both original and modified HOUSES) is promising as address information, is almost routinely collected in healthcare settings (eg, medical records) and is directly linked or geocoded to real property data. Considering that there are high missing rates of number of bedrooms and bathrooms in assessor's real property data, our study findings provide important evidence supporting use of the modified HOUSES index as a potential alternative to the original HOUSES index in studying and addressing health disparities. Overall, the modified HOUSES index provides an alternative approach for measuring SES when conventional data for characterising SES is not available.

One strength of the current study is that it was conducted in two study settings with diverse socioeconomic characteristics (external validity). The robust performance of modified HOUSES in these communities demonstrates that this approach to characterising SES is feasible and generalisable. Although it is not a strength of the current study, using the modified HOUSES index minimises effort for imputing missing information in the real property data set.

A limitation of the study is that self-reported health outcomes are subject to reporting bias. The associations between self-reported health outcomes and SES, however, have been well demonstrated in multiple independent investigations. Furthermore, these same health outcomes, defined by physician diagnosis or predetermined criteria, were also significantly associated with our original HOUSES index.7–13 The performance of modified HOUSES for objective measure-based health outcomes can be expected to be similar to these findings. HOUSES, which is developed based on real property data for US taxation purposes, may not work well in other countries where housing data are not routinely collected or made publicly available in databases, or even in communities within the USA where housing assessments are infrequent or of poor quality. Furthermore, the formulation of modified HOUSES was performed relying on the relationship among four housing characteristics observed in the two Midwestern counties. Therefore, it is possible that the modified HOUSES may not work as well as the original HOUSES in communities where the relationship among those four characteristics is drastically different compared with the two counties used in this study. Additionally, the use of assessed values without other more objective measures for housing features may make the modified HOUSES index more susceptible to a potential bias when comparisons are made among communities in which widely different assessment procedures are used. Further research might focus on assessing and reducing any potential biases. The modified HOUSES index is likely to be more robust when used in a single community for determining SES of individuals and families.

In conclusion, a modified HOUSES calculation, using two housing-related characteristics (assessed housing value and square footage) instead of four, highly correlates with the ability of the original HOUSES index to represent SES, especially in US Midwestern communities. The two modified HOUSES components are commonly captured in assessor's housing data. As a result, the modified HOUSES improves the feasibility of comprehensively assessing SES, expanding the application of this tool into different geographic regions that do not routinely collect the real property data needed for the original HOUSES index.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Kelly Okeson and Ms Elizabeth Krusemark for their editorial peer review for the manuscript. Collection and validation of the Jackson County data was facilitated by Joan Pu, City of Kansas City, Missouri, and Mark Funkhouser, PhD, then Mayor of Kansas City, Missouri.

Footnotes

Contributors: ER, C-IW and YJJ were responsible for the study design, initial manuscript drafting and interpretation of the results. The original study design for and formulation of HOUSES was done by ARW and YJJ. C-IW, PHW, JAS, BPY, TJB, ARW and YJJ were responsible for procedures used to collect the data for the original HOUSES. SSC and PHW contributed critically for manuscript drafting. ER and SMA conducted the statistical analysis in this paper. Earlier statistical analyses for the basis of HOUSES were done by ARW. All the authors had approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01 HL126667), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R21 AI101277, R21 AI116839), and T. Denny Sanford Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Boards at the University of Northern Iowa (for conducting telephone interviews) and Mayo Clinic approved the consent and study procedures.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Diez Roux AV. Conceptual approaches to the study of health disparities. Annu Rev Public Health 2012;33:41–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N et al. Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: the National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1608–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:167–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005;365:1099–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oakes JM, Rossi PH. The measurement of SES in health research: current practice and steps toward a new approach. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:769–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Neighborhoods and Health: Oxford University Press, Inc, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butterfield MC, Williams AR, Beebe T et al. A two-county comparison of the HOUSES index on predicting self-rated health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juhn YJ, Beebe TJ, Finnie DM et al. Development and initial testing of a new socioeconomic status measure based on housing data. J Urban Health 2011;88:933–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson MD, Urm SH, Jung JA et al. Housing data-based socioeconomic index and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease: an exploratory study. Epidemiol Infect 2013;141:880–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bang DW, Manemann SM, Gerber Y et al. A Novel Socioeconomic Measure Using Individual Housing Data in Cardiovascular Outcome Research. Int J Env Res Pub He 2014;11:11597–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juhn Y, Krusemark E, Rand-Weaver J et al. A novel measure of socioeconomic status using individual housing data in health disparities research for asthma in adults. Allergy 2014;69:327–27. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris MN, Lundien MC, Finnie DM et al. Application of a novel socioeconomic measure using individual housing data in asthma research: an exploratory study. Npj Prim Care Resp M 2014;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghawi H, Crowson CS, Rand-Weaver J et al. A novel measure of socioeconomic status using individual housing data to assess the association of SES with rheumatoid arthritis and its mortality: a population-based case-control study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollingshead A. Four Factor Index of Social Status: New Haven, CT: Yale University Department of Psychology, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rieppi R, Greenhill LL, Ford RE et al. Socioeconomic status as a moderator of ADHD treatment outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:269–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakao K. The 1989 Socioeconomic index of occupations: Construction from the 1989 Occupational Prestige Scores (General Social Survey Methodological Report No 74): Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, National Opinion Research Center, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y. Cross-national comparison of childhood obesity: the epidemic and the relationship between obesity and socioeconomic status. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:1129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker JD, Schoendorf KC, Kiely JL. Associations between measures of socioeconomic status and low birth weight, small for gestational age, and premature delivery in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 1994;4:271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitlock G, MacMahon S, Vander Hoorn S et al. Association of environmental tobacco smoke exposure with socioeconomic status in a population of 7725 New Zealanders. Tob Control 1998;7:276–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reidgeway G. Generalized Boosted Models. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkinson EJ, Therneau TM, Melton LJ et al. Assessing fracture risk using gradient boosting machine (GBM) models. J Bone Miner Res 2012;27:1397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natekin A, Knoll A. Gradient boosting machines, a tutorial. Front Neurorobot 2013;7:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]