Abstract

Objective

Sarcopaenia and physical function impairment may have a greater effect on survival than other clinical characteristics, including multimorbidity. In this study, we evaluated the impact of sarcopaenia on all-cause mortality and the interaction among muscle loss, physical function impairment and multimorbidity on mortality risk over 10 years in older community-dwellers.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Population-based study.

Participants

All persons aged 80+ years living in the community in the Sirente geographic area (L'Aquila, Italy) (n=364). Participants were categorised in the sarcopaenic or non-sarcopaenic group based on the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People criteria.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

(1) All-cause mortality over 10 years according to the presence of sarcopaenia and (2) impact of physical function impairment, assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), and multimorbidity on 10-year mortality risk in persons with sarcopaenia.

Results

Sarcopaenia was identified in 103 participants (29.1%). A total of 253 deaths were recorded over 10 years: 90 among sarcopaenic participants (87.4%) and 162 among non-sarcopaenic persons (65.1%; p<0.001). Participants with sarcopaenia had a higher risk of death than those without sarcopaenia (HR=2.15; 95% CI 1.02 to 4.54). When examining the effect of sarcopaenia and physical function impairment on mortality, participants with low physical performance levels showed greater mortality. Conversely, the mortality risk was unaffected by multimorbidity.

Conclusions

Our findings show that physical function impairment, but not multimorbidity, is predictive of mortality in older community-dwellers with sarcopaenia. Hence, in sarcopaenic older persons, interventions against functional decline may be more effective at preventing or postponing negative health outcomes than those targeting multimorbidity.

Keywords: sarcopenia, physical function, disability, frail elderly, adverse outcome, co-morbidity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The association between sarcopaenia and adverse health outcomes was explored in a well-characterised and relatively large cohort of older persons living in the community.

The association between sarcopaenia and mortality was assessed over a long follow-up and adjusted for several possible confounders.

The observational design of the study allowed the enrolment of community-living older persons without restrictive selection criteria, such as those adopted in randomised clinical trials.

The estimation of muscle mass was based on anthropometric parameters rather than on imaging techniques, such as dual X-ray absorptiometry, computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

Introduction

The age-related loss of muscle mass and function (sarcopaenia) is increasingly recognised as an important risk factor for several negative health-related outcomes.1 Indeed, sarcopaenia is associated with poor endurance, slow gait speed and decreased mobility.1 The muscle decline that accompanies ageing has also been indicated as a major factor in the development of physical frailty and its possible biological substrate.2 3 It is therefore not surprising that sarcopaenia conveys increased risk of incident disability, higher healthcare costs and all-cause mortality.4–6

Remarkably, the association between sarcopaenia and mortality appears to be independent of age, cardiovascular or respiratory diseases, or the comorbidity burden.4 This finding suggests that the physical function impairment intrinsic to sarcopaenia could underlie the link between muscle loss and adverse health outcomes.7 Notably, the functional capacity of an older person is a powerful predictor of negative events, independent of the presence and number of disease conditions.8 As such, the functional status is proposed to be a critical target for interventions to restore robustness, improve the quality of life and (possibly) extend survival in late life.7 Whether the physical function impairment intervenes in the relationship between sarcopaenia and mortality has yet to be clearly established.

The present study was therefore undertaken to assess the impact of sarcopaenia on all-cause mortality over 10 years of follow-up in a population of frail octogenarians and nonagenarians enrolled in the ‘Invecchiamento e Longevità nel Sirente’ (Aging and Longevity in the Sirente geographic area, ilSIRENTE) study. The influence of physical function impairment and multimorbidity on mortality among sarcopaenic participants was also explored.

Methods

The ilSIRENTE study is a prospective cohort study conducted in the mountain community living in the Sirente geographic area (L'Aquila, Abruzzo) in Central Italy. The study was designed by the Department of Geriatrics, Neurosciences and Orthopaedics of the Catholic University of Sacred Heart (Rome, Italy) and developed by the teaching nursing home ‘Opera Santa Maria della Pace’ (Fontecchio, L'Aquila, Italy), in a partnership with local administrators and primary care physicians of Sirente Mountain Community Municipalities.

All participants signed an informed consent form at the baseline visit. The ilSIRENTE study protocol is fully described elsewhere.9

Study population

A preliminary list of persons living in the Sirente area was obtained at the end of October 2003 from the Registry Offices of the 13 municipalities involved in the study. Potential participants were identified by selecting all persons born in the Sirente area before 1 January 1924 and living locally at the time of the survey. Among the eligible persons (n=429), the prevalence of refusal was very low (16%). Age and gender distribution were not different between people who refused to participate and the enrollees. The overall sample population enrolled in the ilSIRENTE study consisted of 364 persons. The present analysis was conducted in 354 participants, after excluding 10 persons with missing data for the variables of interest.

Data collection

Baseline assessments of participants began in December 2003 and were completed in September 2004. The Minimum Data Set for Home Care (MDS-HC) form was administered to all study participants following the guidelines published in the MDS-HC manual.10 The MDS-HC form contains over 350 data elements, including sociodemographics, physical and cognitive status variables, as well as major clinical diagnoses and an extensive array of signs, symptoms, syndromes and treatments.10 The MDS items have shown excellent inter-rater and test-retest reliability when completed by nurses performing usual assessment duties (average weighted κ=0.8).11 Additional information about lifestyle habits, physical activity and physical function was collected through questionnaires and tests shared with the ‘Invecchiare in Chianti Study’ (InCHIANTI study).12

Identification of sarcopaenia

The presence of sarcopaenia was established according to the criteria released by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP).13 Specifically, the identification of sarcopaenia was based on the documentation of low muscle mass plus either low muscle strength or low physical performance.

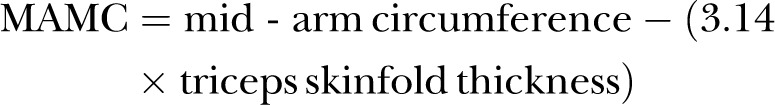

Muscle mass was estimated via the mid-arm muscle circumference (MAMC). MAMC was calculated using the standard formula:14

|

The measurement of triceps skinfold thickness was obtained using a Harpenden Skinfold Caliper, while mid-arm circumference was measured using a standard flexible measuring tape. All measurements were taken on the right arm unless conditions were present that could interfere with the assessment (eg, amputation, lymphoedema, neurological diseases, recent upper extremity fracture, severe osteoarthritis with functional limitation).

In the absence of accepted cut-off values of MAMC for the European population, MAMC tertiles calculated in all ilSIRENTE study participants were considered.15 The lower tertile was considered for identifying participants with low muscle mass. Low muscle mass was therefore defined as an MAMC smaller than 21.1 and 19.2 cm in men and women, respectively.15

Walking speed was evaluated measuring the participant's usual gait speed (m/s) over a 4 m course. As suggested by the EWGSOP,13 a gait speed slower than 0.8 m/s was adopted as the defining criterion for low physical performance. Finally, muscle strength was assessed by using a North Coast handheld hydraulic dynamometer (North Coast Medical, Morgan Hill, CA). Participants performed one familiarisation trial and one measurement trial with each hand, and the result from the stronger side was used for the analyses. According to the EWGSOP,13 low muscle strength was defined as a handgrip strength lower than 30 kg and 20 kg in men and women, respectively.

Physical performance assessment

Physical performance was assessed through the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).16 The battery is composed of three timed tasks: balance, 4 m walk and chair stand tests. The results of each test were rescored from 0 (worst performance) to 4 (best performance), and the summary score (ranging from 0 to 12) was used for the analyses. In previous studies, the SPPB summary score has been shown to be a valid and reproducible parameter able to discriminate small and clinically meaningful differences in physical function and predict different forms of disability in older persons.15–17

Multimorbidity

Clinical diagnoses were recorded by study physicians based on information collected from the participant and his/her general practitioner, physical examination, a careful review of clinical documentation (including laboratory tests and imaging examinations) and medical history. Diagnoses were recorded in the MDS-HC form.10 The presence of multiple conditions was defined as the coexistence of two or more of the following diagnoses: obesity, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral artery disease, hypertension, lung disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema or asthma), osteoarthritis, diabetes, dementia (Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia), Parkinson's disease, renal failure and cancer (non-melanoma skin cancer excluded).

As previously described,18 participants were categorised in three different groups: no multimorbidity (no disease or 1 disease), low multimorbidity (2 clinical conditions) and high multimorbidity (3 or more clinical conditions).

Survival status

Survival status was obtained from general practitioners and confirmed by the National Death Registry. Time to death was calculated from the date of baseline assessment to that of death. All events that occurred over 10 years from enrolment were considered for the analyses.

Covariates

Cognitive performance was assessed using a 6-item, 7-category scale (Cognitive Performance Scale, CPS).10 The CPS was scored on a 6-point ordinal scale, with higher values corresponding to worse cognitive performance. Disability status was assessed through the basic activities of daily living (ADL)19 and instrumental ADL (IADL)20 scales. The ADL scale explores the following tasks: eating, dressing, personal hygiene, mobility in bed, locomotion, use of the toilet and transfer. The scale ranges between 0 and 7, with higher scores indicating more severe impairment. The IADL scale explores meal preparation, shopping, telephone use, housekeeping, medication intake, handling finance and use of transportation. Similar to the ADL scale, the IADL scale ranges between 0 and 7, with higher scores indicating more severe impairment.

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight in kg divided by the square of height in metres. Alcohol abuse was defined as the consumption of more than half a litre of wine (or equivalent quantity of alcohol) per day. Current smoking was defined as the regular use of tobacco (at least once a week) in the last year.

Blood measurements

Venus blood samples were drawn in the morning after an overnight fast using EDTA commercial collection tubes. Samples were immediately centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant, corresponding to the plasma fraction, was collected, aliquoted and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Plasma levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumour necrosis factor α and C reactive protein (CRP) were measured using commercially available ELISA kits on an Olympus 2700 analyser (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). All samples were measured in duplicate, and the average value was used for the analyses.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the study participants are described according to the sarcopaenia status. Data were analysed to obtain descriptive statistics. The normal distribution of continuous variables was ascertained through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables are presented as mean values±SD or as the median (range); categorical variables are presented as an absolute number (percentage). Differences in categorical variables were assessed using Fisher's exact test, whereas the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous variables. For all tests, statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Time to death was calculated from the date of baseline assessment to the date of death. All events that occurred during 10 years of follow-up were considered. Crude and adjusted HRs and 95% CIs for mortality according to the presence of sarcopaenia were calculated using Cox proportional-hazards models. All variables associated with the presence of sarcopaenia at a significance level of p<0.05 at the univariate analysis were entered in the models. Final analyses were therefore adjusted for age and gender (model 1); age, gender, ADL and IADL scores cognitive impairment and BMI (model 2); age, gender, ADL and IADL scores, CPS score, BMI, CRP and IL-6 (model 3). Age, ADL and IADL scores, CPS score, BMI, CRP and IL-6 were treated as continuous variables.

Survival curves of participants were computed according to the Kaplan-Meier method to explore the impact of sarcopaenia on survival. In participants with sarcopaenia, the combined effect of functional impairment and multimorbidity on the risk of death and their potential interaction was also investigated. According to the procedure suggested by Rothman,21 sarcopaenia and multimorbidity were combined into a 3-level variable: sarcopaenia and no multimorbidity (n=27), sarcopaenia and two diseases (n=34), sarcopaenia and three or more diseases (n=42). Similarly, sarcopaenia and physical function impairment were combined into a 4-level variable according to the SPPB summary score: sarcopaenia and SPPB 9–12 (n=21), sarcopaenia and SPPB 6–8 (n=21), sarcopaenia and SPPB 3–5 (n=25), and sarcopaenia and SPPB 0–2 (n=36). Kaplan-Meier curves were adjusted for age and gender. The log-log survival function was examined to rule out departures from the proportionality assumption for each model. The accuracy of mortality prediction by physical function impairment and multimorbidity was estimated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

All analyses were performed using the SPSS 10.0 package (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

The median age of the 354 participants was 84.2 (range 80–102) years, with 236 (67.0%) women. The main characteristics of the study population according to the presence of sarcopaenia are listed in table 1. Compared with sarcopaenic participants, those without sarcopaenia were younger, had a lower prevalence of cognitive impairment and functional disabilities and showed higher BMI. Among the inflammatory biomarkers assayed, CRP and IL-6 showed higher plasma concentrations among participants with sarcopaenia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population according to the presence of sarcopaenia

| Characteristics | Total sample n=354 |

Sarcopaenia n=103 |

No sarcopaenia n=251 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 84.2 (80–102) | 87.5 (800–100) | 83.2 (80–102) | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Women | 236 (67) | 71 (30) | 165 (70) | 0.32 |

| Men | 118 (33) | 32 (27) | 86 (73) | |

| Education (years), mean±SD | 5.1±1.6 | 5.2±1.7 | 5.0±1.6 | 0.29 |

| CPS score, median (range) | 0.4 (0–6) | 0.7 (0–6) | 0.3 (0–6) | 0.001 |

| ADL score, median (range) | 0.4 (0–7) | 0.9 (0–7) | 0.2 (0–7) | <0.001 |

| IADL score, median (range) | 2.5 (0–7) | 4.0 (0–7) | 1.9 (0–7) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 25.6±4.5 | 23.1±3.9 | 26.6±4.3 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse, n (%) | 43 (12) | 11 (11) | 32 (13) | 0.36 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 6 (2) | 1 (0) | 5 (3) | 0.26 |

| Diseases, n (%) | ||||

| Ischaemic heart disease | 42 (12) | 11 (11) | 31 (12) | 0.40 |

| CHF | 20 (6) | 9 (9) | 11 (4) | 0.09 |

| Hypertension | 257 (72) | 68 (67) | 189 (76) | 0.07 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 103 (29) | 35 (34) | 68 (27) | 0.12 |

| COPD | 49 (14) | 19 (18) | 30 (12) | 0.07 |

| Parkinson's disease | 6 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (1) | 0.23 |

| Cancer | 17 (5) | 4 (4) | 13 (5) | 0.41 |

| Osteoarthritis | 69 (19) | 20 (19) | 49 (19) | 0.55 |

| Depression | 90 (25) | 30 (29) | 60 (24) | 0.18 |

| Number of diseases, mean±SD | 2.1±1.2 | 2.2±1.1 | 2.1±1.3 | 0.44 |

| Haematological parameters | ||||

| CRP (mg/dL), mean±SD | 4.1±3.4 | 4.7±4.0 | 3.8±3.1 | 0.04 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL), mean±SD | 2.9±2.5 | 3.5±2.8 | 2.6±2.4 | 0.002 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) mean±SD | 1.9±2.2 | 2.2±1.9 | 1.8±2.3 | 0.09 |

ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPS, Cognitive Performance Scale; CRP, C reactive protein; IADL, instrumental ADL; IL-6, interleukin 6; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor α.

A total of 253 deaths (93 men and 160 women) were recorded during the 10-year follow-up. Ninety (87.4%) participants died among those with sarcopaenia, relative to 162 persons (65.1%) without sarcopaenia (p<0.001). Results from unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazard models are shown in table 2. In the unadjusted model, a direct association was determined between sarcopaenia and mortality (HR 3.67; 95% CI 1.94 to 6.95). The association remained statistically significant after adjusting for a number of potential confounders (age, gender, ADL and IADL scores, CPS score, BMI, and plasma CRP and IL-6) (table 2). In the fully adjusted model, participants with sarcopaenia had a higher risk of death for all causes compared with those without sarcopaenia (HR 2.15; 95% CI 1.02 to 4.54).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted HR of death and 95% CIs in the whole study population

| Unadjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Sarcopaenia | 3.67 (1.94 to 6.95) | 2.91 (1.50 to 5.67) | 2.06 (1.01 to 4.25) | 2.15 (1.02 to 4.54) |

| Age | 1.18 (1.10 to 1.27) | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.20) | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.19) | |

| Gender (female) | 0.48 (0.27 to 0.85) | 0.45 (0.25 to 0.83) | 0.54 (0.29 to 1.00) | |

| ADL impairment | 1.13 (0.86 to 1.48) | 1.08 (1.81 to 1.43) | ||

| IADL impairment | 1.29 (1.06 to 1.56) | 1.28 (1.04 to 1.57) | ||

| Cognitive impairment | 1.16 (0.82 to 1.64) | 1.18 (0.83 to 1.68) | ||

| BMI | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.99) | ||

| CRP | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.11) | |||

| IL-6 | 1.31 (1.00 to 1.57) |

Model 1: adjusted for age and gender.

Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, ADL impairment, IADL impairment, cognitive impairment and BMI.

Model 3: adjusted for age, gender, ADL, IADL impairment, cognitive impairment, BMI, CRP and IL-6.

ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C reactive protein; IADL, instrumental ADL; IL-6, interleukin 6.

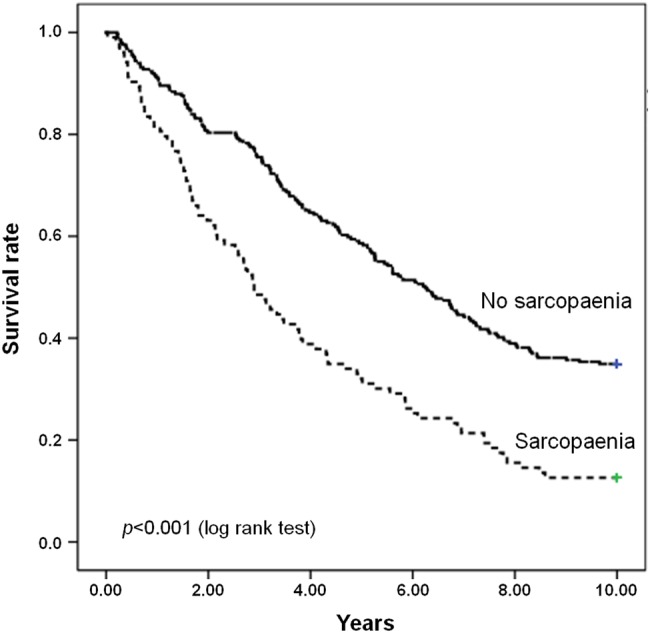

The impact of sarcopaenia on 10-year mortality was also tested by comparing the survival curves according to the presence of sarcopaenia. As depicted in figure 1, survival curves differed significantly at the log-rank test (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Survival curves for participants according to the presence of sarcopaenia at baseline.

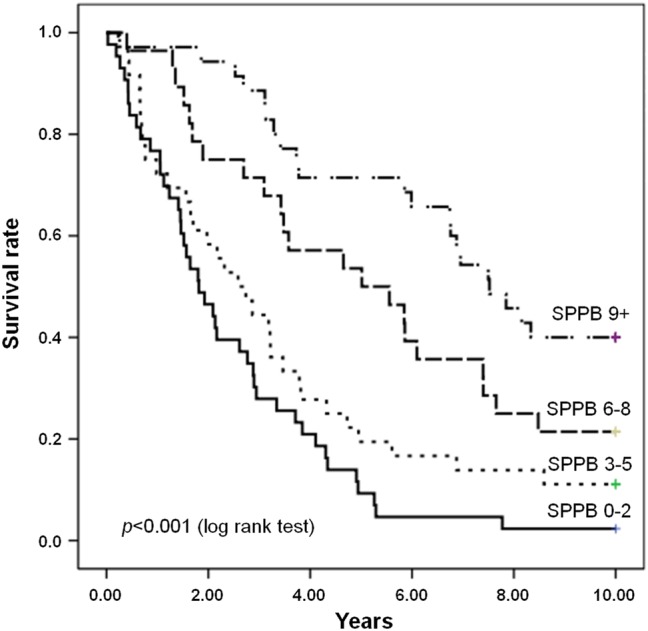

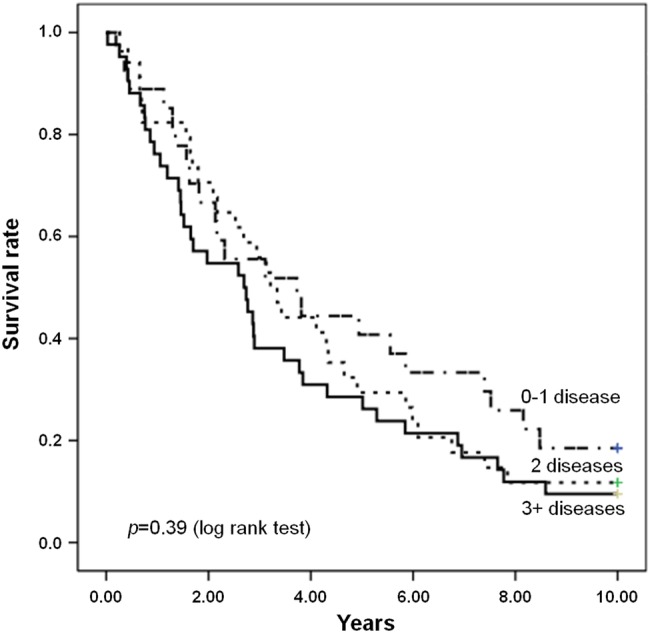

Figures 2 and 3 show the survival curves for participants with sarcopaenia according to the level of physical performance (SPPB score) and multimorbidity status, respectively. As depicted in figure 2, the survival curves differed significantly depending on the SPPB score (p<0.001). Conversely, no significant differences in survival were observed according to multimorbidity (p=0.39) (figure 3). On the basis of ROC curve analysis, physical function impairment showed better predictive accuracy of mortality (area under the ROC curve (AUC) 0.697; 95% CI 0.639 to 0.755) relative to multimorbidity (AUC 0.633; 95% CI 0.572 to 0.695).

Figure 2.

Survival curves for participants with sarcopaenia according to the level of physical function, as indicated by the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) summary score, at baseline.

Figure 3.

Survival curves for participants with sarcopaenia according to the multimorbidity status at baseline.

Discussion

The evaluation of the impact of sarcopaenia on survival among frail older persons is an important and intricate issue. In this study, we explored the association between sarcopaenia and 10-year mortality in a sample of community-dwelling persons aged 80 years or older. We further investigated the specific effects of physical performance and multimorbidity on the relationship between sarcopaenia and 10-year mortality. Our findings show that sarcopaenia, as elaborated by the EWGSOP, is associated with higher mortality rates in older adults living in the community, independent of age, gender and several clinical and biochemical parameters.

Results from this study also show that physical function impairment, not multimorbidity, intervenes in the relationship between sarcopaenia and mortality. Specifically, sarcopaenic participants with poor physical performance, as indicated by lower scores at the SPPB, showed higher mortality rates relative to their well-functioning peers. In contrast, the presence of two or more disease conditions did not impact 10-year mortality of older community-dwellers with sarcopaenia. This finding was further confirmed by the ROC curve analysis that revealed a higher accuracy in predicting mortality of physical function impairment as compared with multimorbidity. This observation is in line with the proposition that physical performance may be a more reliable indicator of a person’s health status than the comorbidity burden.8 18 22

Our results support and extend findings by Arango-Lopera et al,23 who reported a prevalence of sarcopaenia of 33.6% in 345 community-living older adults (mean age 78.5 years; 53.3% females) and an adjusted mortality HR of 2.39 over a 3-year follow-up. As in the present study, the identification of sarcopaenia was based on the EWGSOP criteria, using anthropometry for estimating muscle mass. In contrast, in a community-based study, Hirani et al5 found a much lower prevalence of sarcopaenia (5.3%) among 1705 older men (mean age: 77 years), with an adjusted mortality HR of 1.50 over a median follow-up of 7 years. These contrasting findings can be partially explained by the different criteria adopted for operationalising sarcopaenia (EWGSOP versus Foundation for the National Institute of Health (FNIH) criteria). Indeed, as reported by Dam et al,24 the FNIH criteria will result in a more conservative operationalisation of sarcopaenia, with lower prevalence rates as compared with the EWGSOP definition.

Findings from the present investigation support the proposition that sarcopaenia and physical function impairment are intimately linked with one another in determining adverse health outcomes, including mortality. The evidence that physical function impairment has a greater effect on survival than multimorbidity among sarcopaenic older persons is significant for the clinical practice. Indeed, as highlighted by several geriatric researchers,2 25 26 it is becoming increasingly clear that a substantial ‘re-shaping’ of healthcare systems is necessary to provide programmes and services tailored to the specific needs of our ageing society. In this regard, a fundamental step implies the development models of care focused on the functional status rather than on single diseases.27 Based on the results of this study, the implementation of interventions aimed at preserving or improving physical function (eg, physical exercise and nutrition) may be necessary to extend survival and reduce the demand for long-term care among older persons with sarcopaenia. Hence, the prevention and management of sarcopaenia and physical function decline should represent a major priority for healthcare providers and policymakers.3 27

Some methodological issues may have influenced our results. As in all cohort studies, selective survival before entry into the cohort has to be taken into account. Furthermore, in our longitudinal observational study, results may be confounded by unmeasured factors. In the absence of randomisation, it is cannot be ruled out that differences between groups might have biased the study results. For instance, persons with more severe multimorbidity might have received a higher level of medical care relative to those with milder disease burden, but functionally impaired. However, our homogeneous population of older persons born and living in a well-defined geographical area minimises the possibility that persons with multimorbidity had substantially better healthcare or health knowledge than those without multimorbidity. Another limitation of this study resides in the lack of documentation concerning the cause of death. However, the aim of this investigation was to characterise the impact of sarcopaenia, physical function impairment and multimorbidity on all-cause mortality, rather than identifying the specific cause of death.

The estimation of muscle mass based on anthropometric measures deserves further discussion. While anthropometry is not considered to be the gold standard for measuring body composition,28 previous investigations have shown that MAMC is a suitable proxy of muscle mass in community-based studies,10 29 30 such as the ilSIRENTE. The procedure adopted for muscle strength assessment involved one familiarisation and one measurement trial for each hand. Although it is possible that better performances might have been achieved at a second measurement trial, the procedure was consistent across the study population. Hence, it is unlikely that results at the handgrip strength test could have biased the identification of sarcopaenia. Finally, the study population was composed of persons aged 80 years or older; hence, findings may not be generalisable to other age groups.

In conclusion, our results, obtained from a representative sample of very old and frail persons, provide robust support to the association between sarcopaenia and mortality, suggested by previous investigations.4 5 22 30 31 Furthermore, higher levels of physical function were associated with longer survival in sarcopaenic older adults. As a whole, these observations lend support to the proposition that sarcopaenia and physical function impairment are major determinants of negative health outcomes in advanced age.32 It follows that interventions specifically targeting physical function may provide preventive and therapeutic advantages against the detrimental consequences of sarcopaenia. Future studies should elucidate if the implementation of strategies focusing on the early detection and management of sarcopaenia and physical function decline would result in survival gains at very old age.

Acknowledgments

The ‘Invecchiamento e Longevità nel Sirente’ (ilSIRENTE) study was supported by the ‘Comunità Montana Sirentina’ (Secinaro, L'Aquila, Italy). The authors thank all the participants for their enthusiasm in participating to the project and their patience during the assessments. They are grateful to all the persons working as volunteers in the ‘Protezione Civile’ and in the Italian Red Cross of the Abruzzo Region for their support. They sincerely thank the ‘Comunità Montana Sirentina’ and, in particular, its president who promoted and strongly supported the development of the project. The ilSIRENTE Study Group is composed as follows: Steering Committee: R Bernabei, F Landi. Coordination: A Russo, M Valeri, G Venta. Writing panel: C Barillaro, E Capoluogo, M Cesari, P Danese, L Ferrucci, R Liperoti, G Onder, M Pahor, V Zamboni. Participants: Comune di Fontecchio: P Melonio, G Bernabei, A Benedetti; Comune di Fagnano: N Scarsella, A Fattore, M Fattore; Comune di Tione: M Gizzi; Comune di Ovindoli: S Angelosante, E Chiuchiarelli; Comune di Rocca di Mezzo: S Pescatore; Comune di Rocca di Cambio: G Scoccia; Comune di Secinaro: G Pizzocchia; Comune di Molina Aterno: P Di Fiore; Comune di Castelvecchio: A Leone; Comune di Gagliano Aterno: A Petriglia; Comune di Acciano: A Di Benedetto; Comune di Goriano Sicoli: N Colella; Comune di Castel di Ieri: S Battista; RSA Opera Santa Maria della Pace: A De Santis, G Filieri, C Gobbi, G Gorga, F Cocco, P Graziani.

Footnotes

Contributors: FL is the principal investigator of the ilSIRENTE Study and conducted the statistical analysis. RC and AMM assisted with data interpretation. MT and EM drafted the manuscript. RB and GO assisted with reviewing.

Funding: The study was also partly supported by grants from the Innovative Medicines Initiative—Joint Undertaking (IMI-JU #115621) and intramural research grants from the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart (D3.2 2013 and D3.2 2015).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki on medical protocol and ethics and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available by emailing the corresponding author at francesco.landi@rm.unicatt.it

References

- 1.Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. BMJ 2010;341:c4097 10.1136/bmj.c4097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cesari M, Landi F, Vellas B et al. Sarcopenia and physical frailty: two sides of the same coin. Front Aging Neurosci 2014;6:192 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landi F, Calvani R, Cesari M et al. Sarcopenia as the biological substrate of physical frailty. Clin Geriatr Med 2015. 31:367–74. 10.1016/j.cger.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landi F, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Liperoti R et al. Sarcopenia and mortality risk in frail older persons aged 80 years and older: results from ilSIRENTE study. Age Ageing 2013;42:203–9. 10.1093/ageing/afs194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirani V, Blyth F, Naganathan V et al. Sarcopenia is associated with incident disability, institutionalization, and mortality in community-dwelling older men: the CONCORD health and ageing in men project. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:607–13. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT et al. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:80–5. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Working Group on Functional Outcome Measures for Clinical Trials. Functional outcomes for clinical trials in frail older persons: time to be moving. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:160–4. 10.1093/gerona/63.2.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.St John PD, Tyas SL, Menec V et al. Multimorbidity, disability, and mortality in community-dwelling older adults. Can Fam Physician 2014;60:e272–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landi F, Russo A, Cesari M et al. The ilSIRENTE study: a prospective cohort study on persons aged 80 years and older living in a mountain community of Central Italy. Aging Clin Exp Res 2005;17:486–93. 10.1007/BF03327416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris JN, Fries BE, Steel K et al. Comprehensive clinical assessment in community setting: applicability of the MDS-HC. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:1017–24. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02975.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landi F, Tua E, Onder G et al. Minimum data set for home care: a valid instrument to assess frail older people living in the community. Med Care 2000;38:1184–90. 10.1097/00005650-200012000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E et al. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:1618–25. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03873.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010;39:412–23. 10.1093/ageing/afq034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antonelli Incalzi R, Landi F, Cipriani L et al. Nutritional assessment: a primary component of multidimensional geriatric assessment in the acute care setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996;44:166–74. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landi F, Russo A, Liperoti R et al. Midarm muscle circumference, physical performance and mortality: results from the aging and longevity study in the Sirente geographic area (ilSIRENTE study). Clin Nutr 2010;29:441–7. 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the Short Physical Performance Battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55A:M221–31. 10.1093/gerona/55.4.M221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landi F, Russo A, Liperoti R et al. Anorexia, physical function, and incident disability among the frail elderly population: results from the ilSIRENTE study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2010;11:268–74. 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.12.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A et al. Disability, more than multimorbidity, was predictive of mortality among older persons aged 80 years and older. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:752–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW et al. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963;185:914–19. 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179–86. 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Concepts of interaction. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, eds. Modern epidemiology. 2nd edn Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1998:329–42. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 2011;305:50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arango-Lopera VE, Arroyo P, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM et al. Mortality as an adverse outcome of sarcopenia. J Nutr Health Aging 2013;17:259–62. 10.1007/s12603-012-0434-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dam TT, Peters KW, Fragala M et al. An evidence-based comparison of operational criteria for the presence of sarcopenia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69:584–90. 10.1093/gerona/glu013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R, Mortality Review Group; FALCon and HALCyon Study Teams . Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c4467 10.1136/bmj.c4467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue QL, Walston JD, Fried LP et al. Prediction of risk of falling, physical disability, and frailty by rate of decline in grip strength: the women's health and aging study. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1119–21. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cesari M, Marzetti E, Thiem U et al. The geriatric management of frailty as paradigm of “The end of the disease era”. Eur J Intern Med 2016;31:11–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cesari M, Fielding RA, Pahor M et al. Biomarkers of sarcopenia in clinical trials-recommendations from the International Working Group on Sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2012;3:181–90. 10.1007/s13539-012-0078-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landi F, Onder G, Russo A et al. Calf circumference, frailty and physical performance among older adults living in the community. Clin Nutr 2014;33:539–44. 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L et al. Decreased muscle mass and increased central adiposity are independently related to mortality in older men. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:1339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing 2014;43:748–59. 10.1093/ageing/afu115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landi F, Liperoti R, Fusco D et al. Sarcopenia and mortality among older nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:121–6. 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myint PK, Welch AA. Healthier ageing. BMJ 2012;344:e1214 10.1136/bmj.e1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]