Abstract

Background:

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) is a debilitating disease in orthopedics, frequently progressing to femoral head collapse and osteoarthritis. It is thought to be a multifactorial disease. ONFH ultimately results in femoral head collapse in 75–85% of untreated patients. Total hip arthroplasty (THA) yields satisfactory results in the treatment of the end stage of the disease. However, disease typically affects males between the ages of 20 and 40 years and joint replacement is not the ideal option for younger patients. Recently, mesenchymal stem cells and platelet rich plasma (PRP) have been used as an adjunct to core decompression to improve clinical success in the treatment of precollapse hips.

Materials and Methods:

A prospective study of 40 hips in 30 patients was done. There were 19 males and 11 females with a mean age 36.7 ± 6.93 years. The indication for the operation was restricted primarily to modified Ficat stages IIb and III. 16 hips (40%) had stage IIb and 24 hips (60%) had stage III ONFH. The period of follow up ranged between 36–50 months with a mean 41.4 ± 3.53 months. All patients were assessed clinically during pre- and post-operative period according to the Harris Hip Score (HHS), Visual Analog Score (VAS) and radiologically by X-rays. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done preoperatively to confirm the diagnosis and every 6 months postoperatively for assessment of healing. The operative procedure include removal of necrotic area with drilling then the cavity was filled with a composite of bone graft mixed with PRP.

Results:

The mean HHS improved from 46.0 ± 7.8 preoperatively to 90.28 ± 19 at the end of followup (P < 0.0001). The mean values of VAS were 78 ± 21 and 35 ± 19 at preoperatively period and final followup, respectively, with an average reduction of 43 points.

Conclusion:

We found that the use of PRP with collagen sheet can increase the reparable capacity after drilling of necrotic segment in stage IIb and III ONFH.

Keywords: Collagen sheet, core decompression, osteonecrosis, platelet rich plasma

MeSh terms: Osteonecrosis, femur head, platelet-derived growth factor, visual analog pain scale

INTRODUCTION

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) is a debilitating disease.1,2,3 The etiology of the disease is unknown.4,5 However, it is thought to be multifactorial.6,7,8 It results in femoral head collapse in 75–85% of untreated patients.9,10,11,12,13,14 The current trend in the treatment of ONFH aims to preserve the joint in the initial stages and to delay the replacement surgery in advanced cases.14,15,16,17,18,19 Recently, mesenchymal stem cells and PRP have been used as an adjunct to core decompression to improve clinical success in the treatment of precollapse hips.20,21,22,23 PRP was first described by Whitman et al. in 1997,24 it is an autologous preparation that concentrates platelets in a small volume of plasma. It contains multiple growth factors and has been shown to have positive effects on the stimulation of bones, blood vessels and the formation of chondrocytes.24,25

This study describes early results of treatment ONFH by replacement of the necrotic segment after multiple drilling with bone graft and PRP covered by collagen sheet to augment healing process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

30 patients (40 hips) with modified Ficat stages IIb and III ONFH [Table 1].26 underwent surgery between December 2009 and March 2014. There were 19 males and 11 females with a mean age 36.7 ± 6.93 years (range 20–48 years). The causes of osteonecrosis in this series were steroid intake (n = 15, 37.5%), post traumatic (n = 5, 12.5%), idiopathic (n = 20, 50%). In 10 patients, the procedure was performed bilaterally with average 3.5 months interval (2.8–4.6 months). 16 hips (40%) had stage IIb and 24 hips (60%) had stage III ONFH. The mean followup was 41.4 ± 3.53 months (range 36–50 months). All the patients were assessed clinically during pre- and postoperative period according to the HHS,14 VAS27 and radiologically by X-rays. MRI was done preoperatively to confirm the diagnosis and every 6 months postoperatively for assessment of healing. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Stage IIb or III ONFH as evidenced radiologically (2) age between 20 and 50 years (3) disabling pain that interfered with daily activity. The exclusion criteria were (1) active endocrine disorder (e.g. hypothyroidism) (2) active neurological disorder that might affect the patient's pain (e.g. peripheral neuropathy and multiple sclerosis) (3) any active disease requiring continuous use of corticosteroids (e.g., rheumatoid and systemic lupus erythematosis).

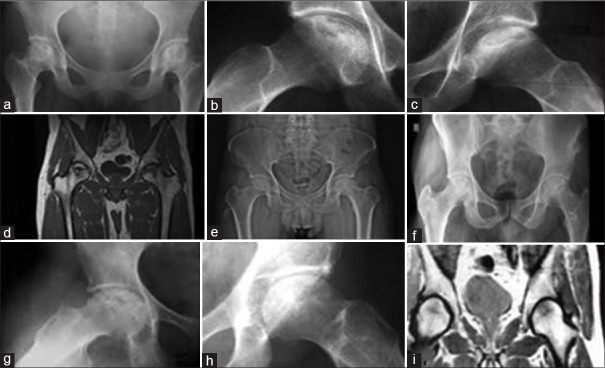

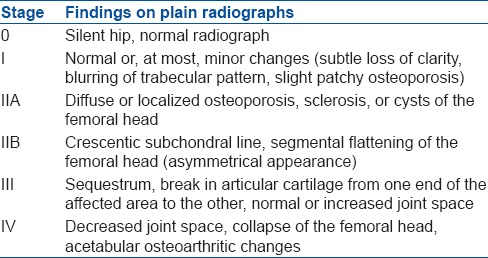

Table 1.

Modified Ficat classification

Operative procedure

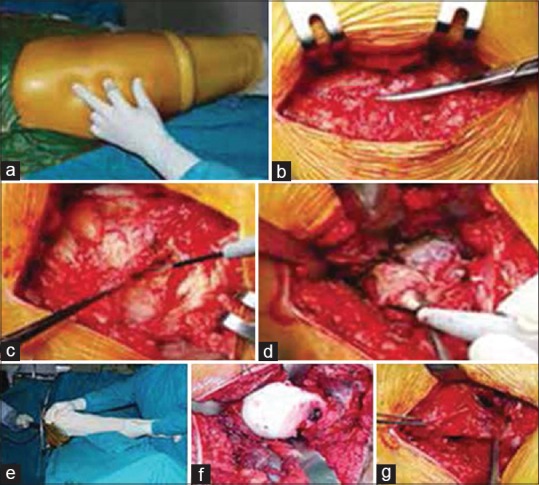

Under general or regional anesthesia, the patient was placed on a standard operating table in a supine position with the buttock of the affected side sticks a few centimeters out of the border of the table. The skin incision began about 2 cm proximal to the tip of the greater trochanter and extended for 7–8 cm distally. The incision was angled about 25° with respect to the axis of the femoral shaft. After dissection of subcutaneous tissues, the fascia of the muscles was dissected in line of incision. The anterior margin of the gluteus medius was cut for about 4–5 cm at its insertion onto the greater trochanter. The gluteus minimus was then identified below the gluteal medius and was separately dissected, taking care to maintain about 0.5 cm of tissue distally to allow an easier reconstruction. Three Hohmann retractors were used to expose the hip capsule. Two were placed at 11 and 2 o’clock, while the third was placed at 9 o’clock for the right hip and at 3 o’clock for the left one. These retractors proximally and superiorly shifted the glutei and medially shift the rectus femoris and iliopsoas. The hip capsule was then tensioned by forcing the hip in flexion, adduction and external rotation and then a reversed T-shaped incision was performed. The hip was dislocated anteriorly, with care not to damage the posterior capsule [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Surgical approach, (a) patient positioning, (b) iliotibial band incision, (c and d) incision of anterior fibers of gluteus medius, minimus and capsule, (e and f) anterior dislocation of the hip joint, (g) repair of the gluteus medius and minimus at the end of the procedure

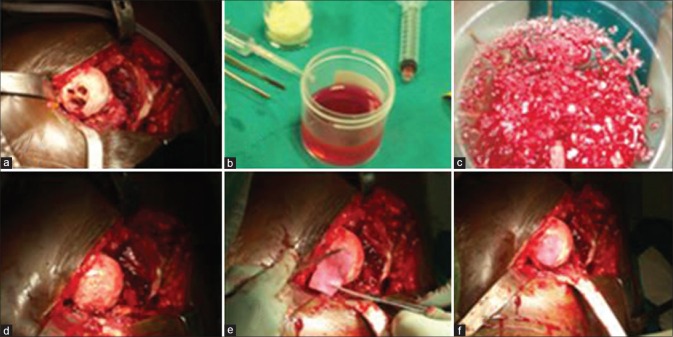

The necrotic area of the femoral head was identified and approached through the damaged articular surface, then curetted with the removal of all necrotic bone. Multiple drilling was done with a 4.5 mm drill bit for 1-5 cm depth. The cavity was filled with a composite of iliac bone graft mixed with PRP. The PRP must be used within 6 h of preparation. Finally, the cavity was covered with collagen sheet made of porcine collagen type I membrane. It consisted of 4.8 mg/ml rat tail collagen type I gel, the diameter of the samples was 9 mm with a height of 3 mm and stored at 4°C until implanted. (A Biocollagen MeRG® Collagen Membrane, Bioteck, Vicenza, Italy) and fixed with fibrin glue to the articular surface [Figure 2]. Gentle reduction was done and the anterior capsule was repaired.

Figure 2.

Operative technique, (a) stage III osteonecrosis of the femoral head after curettage and multiple drilling, (b) platelet rich plasma (c) composite of platelet rich plasma and bone graft (d) femoral head after impaction of bone graft and platelet rich plasma (e and f) coverage with collagen sheet

The procedure for preparation of PRP consisted of 150-ml venous blood sample that was centrifuged twice for 10 and 15 min, respectively, to concentrate and produce 20 ml of PRP.28

Postoperatively, skin traction was applied for 3 days, with the functional training of the hip. Partial weight bearing with crutches was allowed after 6 weeks. Full weight bearing started at the beginning of the 3rd months and heavy physical activity up to 1 year postoperatively. All patients completed the followup till the end of the study. They were followed up at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and at 1 year then every 6 months. At each followup, clinical evaluation was done according to VAS27 and HHS.14 In addition to radiological evaluation by X-rays (anteroposterior and lateral views), MRI study was done every 6 months. Each hip of patients with bilateral hip involvement was examined separately.

Statistical analysis

The following tests were used: (1) The nonparametric Wilcoxon test - To compare the average of the subjective pain difference (difference between preoperative and postoperative followup as determined by the visual analog score [VAS]) and the joint function (as measured by HHS comparing preoperative function with function at followup). (2) The Kruskal–Wallis test - this test was used to study the difference between the subjective pain and HHS parameters based on the length of followup. Clinical success was defined as a good or excellent HHS score, improvement in VAS and no revision surgery.

RESULTS

There were no significant complications in any patient who underwent this procedure. Two patients were noted to have postoperative trochanteric bursitis at immediate followup and one case of deep venous thrombosis, however, these were managed nonoperatively.

The average values of VAS were 78 ± 21 and 35 ± 19 at preoperative and final followup, respectively, with an average reduction of 43 points. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). Significant pain relief was reported in 34 hips (85%), while the rest of patients reported little or no pain relief. As regards improvement in VAS, there was no significant difference between stage IIb and III ONFH, risk factors, age, gender, or bilateral treatment. HHS improved from 46.0 ± 7.8 preoperatively to 90.28 ± 19 at the end of followup. The comparison between average scores showed statistical significant difference (P < 0.0001) [Figures 3 and 4].

Figure 3.

Stage IIb (a and b) subchondral collapse is indicated by the appearance of a crescent sign without flattening of the femoral head. The lateral radiograph shows a typical crescent sign, (c and d) preoperative magnetic resonance imaging showing avascular necrosis changes (e) immediate postoperative X-ray showing adequate curettage and filling with composite of pla telet rich plasma and bone graft, (f) 6 months followup postoperative x-ray showing healing (g) 25 months followup postoperative x-ray showing healing of lesion

Figure 4.

(a) Preoperative x-ray pelvis showing both hips anteroposterior view showing bilateral stage III osteonecrosis of the femoral head (b and c) preoperative frog lateral view of both hips showing bilateral avascular necrosis changes (d) preoperative magnetic resonance imaging showing avascular changes (e) immediate postoperative x-ray pelvis anteroposterior view showing curettage and filling with composite of platelet rich plasma, 30 months postoperative followup anteroposterior (f) and frog leg lateral views of (g,h) both hips showing healing changes (i) 30 months followup postoperative magnetic resonance imaging showing healing changes

Twenty seven hips (67.5%) had excellent results and nine hips (22.5%) had a good result. Four hips (10%) had fair results. These patients walked with a painful limp and were prepared for THA. Patients with stage IIb has better improvement in HHS than stage III, but this was statistically insignificant.

Radiologically, one hip at stage IIb progressed to stage III and one hip at stage III progressed to stage IV. Unchanged radiological appearance over the followup period was observed in three hips (7.5%), but with improvement in functional score and patient satisfaction. All other hips showed evident radiological signs of regeneration and sound healing.

DISCUSSION

Although options to halt the progression of ONFH are available (e.g. core decompression, osteotomy, vascularized fibular graft and medical treatments), the results have been disappointing, with up to 40% of patients progressing to THA. There is no agreement on the best surgical method for ONFH. Conceptually, the best option is removal of the necrotic bone from the femoral head and replacement with a viable and structurally-sound bone, thus restoring vitality to the femoral head, preventing collapse of the articular surface and delaying THA.29,30 Of the various treatment options available to avoid THA, core decompression, as described originally by Ficat et al.31 and later by Mont et al.2 is one of the most commonly used surgical treatments for ONFH.2,31 Core decompression may be a suitable option for stage I or IIA but the main problem is with more advanced stages, especially in young active patients. Most literatures about management of ONFH try to preserve the hip joint in early stages of the disease, but there is a debate on the efficacy of this treatment in advanced stages, especially with articular damage.32,33,34

The effectiveness of core decompression alone in preventing collapse in ONFH has been a major source of controversy.35,36,37,38,39 A wide range of success rates has been reported for core decompression according to Mont et al.40 63.5% of 1166 hips achieved a satisfactory clinical result after core decompression.40 A retrospective review described a technique that utilized a trephine approach to enter the area of necrosis under fluoroscopy and then inject concentrated bone-marrow directly into this area. It found excellent results in patients who were precollapse (stage I or II). However, in patients who had already collapsed (stage III or IV), 25 out of 44 hips required a THA.23 Keizer et al.41 described the long term results of core decompression and placement of a nonvascularized bone graft with 44% revision rate at a mean of 4 years.41 These results were less satisfactory compared to the results of our technique who reported good to excellent results in 90% with a revision rate of 10% (four hips). On the other hand, our results may be comparable to some reported results with the use of vascularized fibular graft as reported by Zhao et al.34 The procedure was successful in 90% at Ficat III. He also described a modified technique of tantalum rod implantation combined with vascularized iliac grafting for the treatment of ONFH stage II–IV. Their overall success rate of the entire group was 87.5%.34 However, contrast of the others, Chen et al.42 reported that the use of vascularized iliac bone grafting may not be as promising as originally suggested resulting 76% required THA.42

Since progenitor cells may be lacking in the lesion area, newer treatment modalities have been developed to introduce biologically active cells to the areas of necrosis in an attempt to prevent fracture and collapse by restoring the architecture of the femoral head. Hernigou and Beaujean23 first described a technique for injecting mesenchymal stem cells combined with standard core decompression to introduce biological active cells into an area of necrosis, 23 patients with early (precollapse) disease had excellent results, only nine of 145 hips requiring THA. However, among patients who had stage III or greater (25 of 44) hips required THA.23 This may clarify better results we obtained because of direct attacking of the pathology and removal of all necrotic segment as it has been demonstrated that biologically active cells may not be able to survive in the necrotic lesions, in addition to the use of collagen sheet as a scaffold that may increase the repairable capacity of PRP.

Gangji et al.20 reported that the addition of mesenchymal stem cell to core decompression was found to improve its results; he observed that the level of pain was significantly decreased from 37.8 ± 8.4 to 18.5 ± 6.2. This was comparable to our work, in which the average values were 78 ± 21 and 35 ± 19 at preoperative and final followup, respectively, with an average reduction of 43 points. Daltro et al.43 assessed the efficacy and safety of autologous bone-marrow mononuclear cells implantation in necrotic lesions with a significant postoperative increase in the HHS (98.3 ± 2.5 points) compared to preoperative HHS (78.5 ± 6.2 points) (P < 0.001).43 Our results found significant improvement in hip function with success rate 90% [27 hips (67.5%) had excellent results and nine hips (22.5%) had a good result] with improvement of HHS from 46.0 ± 7.8 preoperatively to 90.28 ± 19 postoperatively after 4 years followup.

A thorough review of the literatures, we found an old technique of treatment that may be similar to ours done by Merle D’Aubigné et al.10 who used cancellous bone graft harvested from the iliac crest, have been used to fill the defect in the femoral head after complete evacuation of the necrotic bone.10 These bone graft can be introduced through a cortical window in the femoral neck or via a “trapdoor” through the articular cartilage of the femoral head, after dislocating the femur head and exposing the flap from the chondral surface of the femur head. The necrotic segment is removed with curette and burr. The void is then filled with iliac crest bone graft. This was first performed in conjunction with an osteotomy by Ganz and Büchler.44 Mont et al.45 had reported their observations with this procedure in 24 Ficat stage III and six stage IV hips. With an average followup of 56 months, 73% their patients had good to excellent results.45 Our results were much better than that recorded by Mont et al.,45 although the similarity of both techniques that can be explained by the improvement of healing and positive reparable effect of PRP with collagen sheet scaffold that was used in our research.

There are some limitations to our study including small sample size and short term of followup. Accordingly, prospective, randomized, controlled studies with large sample size are necessary to verify the therapeutic effects of PRP. However, according to our present results, we are optimistic that this novel approach may lead to a successful outcome in the treatment of advanced stages of ONFH.

To conclude, in young active adult, the use of PRP with collagen sheet scaffold can increase the reparable capacity after adequate curettage and drilling of necrotic segment with the addition of bone graft in stage IIb and III ONFH.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Castro FP, Jr, Harris MB. Differences in age, laterality, and Steinberg stage at initial presentation in patients with steroid-induced, alcohol-induced, and idiopathic femoral head osteonecrosis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:672–6. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(99)90221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mont MA, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: Ten years later. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1117–32. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaulé PE, Campbell PA, Hoke R, Dorey F. Notching of the femoral neck during resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: A vascular study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:35–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B1.16682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldridge JM, 3rd, Urbaniak JR. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head: Etiology, pathophysiology, classification, and current treatment guidelines. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2004;33:327–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao D, Cui D, Wang B, Tian F, Guo L, Yang L, et al. Treatment of early stage osteonecrosis of the femoral head with autologous implantation of bone marrow-derived and cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Bone. 2012;50:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones LC, Jr, Ramirez S, Doty SB. Procoagulants and osteonecrosis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:783–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Osteonecrosis: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:443–9. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000127829.34643.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson ML, Larson AN, Moran SL, Cooney WP, Amrami KK, Berger RA. Clinical comparison of arthroscopic versus open repair of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:675–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mont MA, Hungerford DS. Non-traumatic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:459–74. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199503000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merle D’Aubigné R, Postel M, Mazabraud A, Massias P, Gueguen J, France P. Idiopathic necrosis of the femoral head in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47:612–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei SY, Esmail AN, Bunin N, Dormans JP. Avascular necrosis in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieberman JR, Berry DJ, Mont MA, Aaron RK, Callaghan JJ, Rajadhyaksha AD, et al. Osteonecrosis of the hip: Management in the 21 st century. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:337–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flóris I, Bodzay T, Vendégh Z, Gloviczki B, Balázs P. Short-term results of total hip replacement due to acetabular fractures. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi. 2013;24:64–71. doi: 10.5606/ehc.2013.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: Treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrigliano FA, Lieberman JR. Osteonecrosis of the hip: Novel approaches to evaluation and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465:53–62. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3181591c92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenschenk A, Lautenbach M, Schwetlick G, Weber U. Treatment of femoral head necrosis with vascularized iliac crest transplants. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;386:100–5. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200105000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lieberman JR. Core decompression for osteonecrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:29–33. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scully SP, Aaron RK, Urbaniak JR. Survival analysis of hips treated with core decompression or vascularized fibular grafting because of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1270–5. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199809000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yen YM, Kocher MS. Chondral lesions of the hip: Microfracture and chondroplasty. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2010;18:83–9. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181de1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gangji V, Toungouz M, Hauzeur JP. Stem cell therapy for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5:437–42. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gangji V, Hauzeur JP, Matos C, De Maertelaer V, Toungouz M, Lambermont M. Treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head with implantation of autologous bone-marrow cells. A pilot study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1153–60. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernigou P, Poignard A, Manicom O, Mathieu G, Rouard H. The use of percutaneous autologous bone marrow transplantation in nonunion and avascular necrosis of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:896–902. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.16289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernigou P, Beaujean F. Treatment of osteonecrosis with autologous bone marrow grafting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;405:14–23. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitman DH, Berry RL, Green DM. Platelet gel: An autologous alternative to fibrin glue with applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1294–9. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beltran J, Knight CT, Zuelzer WA, Morgan JP, Shwendeman LJ, Chandnani VP, et al. Core decompression for avascular necrosis of the femoral head: Correlation between long term results and preoperative MR staging. Radiology. 1990;175:533–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.2.2326478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ficat RP. Idiopathic bone necrosis of the femoral head. Early diagnosis and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:3–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B1.3155745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warden V, Hurley AC, Volicer L. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4:9–15. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000043422.31640.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filardo G, Kon E, Pereira Ruiz MT, Vaccaro F, Guitaldi R, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma intraarticular injections for cartilage degeneration and osteoarthritis: Single- versus double-spinning approach. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:2082–91. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1837-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soucacos PN, Beris AE, Malizos K, Koropilias A, Zalavras H, Dailiana Z. Treatment of avascular necrosis of the femoral head with vascularized fibular transplant. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;386:120–30. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200105000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urbaniak JR, Coogan PG, Gunneson EB, Nunley JA. Treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head with free vascularized fibular grafting. A long term followup study of one hundred and three hips. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:681–94. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199505000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ficat P, Arlet J, Vidal R, Ricci A, Fournial JC. Therapeutic results of drill biopsy in primary osteonecrosis of the femoral head (100 cases) Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1971;38:269–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rijnen WH, Gardeniers JW, Buma P, Yamano K, Slooff TJ, Schreurs BW. Treatment of femoral head osteonecrosis using bone impaction grafting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:74–83. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096823.67494.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pavlovcic V, Dolinar D, Arnez Z. Femoral head necrosis treated with vascularized iliac crest graft. Int Orthop. 1999;23:150–3. doi: 10.1007/s002640050334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao D, Xu D, Wang W, Cui X. Iliac graft vascularization for femoral head osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;442:171–9. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000181490.31424.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Camp JF, Colwell CW., Jr Core decompression of the femoral head for osteonecrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:1313–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warner JJ, Philip JH, Brodsky GL, Thornhill TS. Studies of nontraumatic osteonecrosis. The role of core decompression in the treatment of nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;225:104–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hopson CN, Siverhus SW. Ischemic necrosis of the femoral head. Treatment by core decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:1048–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Learmonth ID, Maloon S, Dall G. Core decompression for early atraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:387–90. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B3.2341433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones JP., Jr . In: Osteonecrosis. Arthritis and Allied Conditions: A Textbook of Rheumatology. 12th ed. McCarty DJ, Koopmann WJ, editors. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1993. pp. 1677–96. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mont MA, Carbone JJ, Fairbank AC. Core decompression versus nonoperative management for osteonecrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;324:169–78. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199603000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keizer SB, Kock NB, Dijkstra PD, Taminiau AH, Nelissen RG. Treatment of avascular necrosis of the hip by a non-vascularised cortical graft. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:460–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B4.16950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen CC, Lin CL, Chen WC, Shih HN, Ueng SW, Lee MS. Vascularized iliac bone-grafting for osteonecrosis with segmental collapse of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2390–4. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daltro GC, Fortuna VA, de Araújo SA, Lessa PI, Sobrinho UA, Borojevic R. Femoral head necrosis treatment with autologous stem cells in sickle cell disease. Acta Orthop Bras. 2008;16:44–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ganz R, Büchler U. Overview of attempts to revitalize the dead head in aseptic necrosis of the femoral head – Osteotomy and revascularization. Hip. 1983:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mont MA, Einhorn TA, Sponseller PD, Hungerford DS. The trapdoor procedure using autogenous cortical and cancellous bone grafts for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:56–62. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b1.7989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]