Abstract

Biosynthesis of ecdysteroids, the insect steroid hormones controlling gene expression during molting and metamorphosis, takes place primarily in the prothoracic gland (PG). The activity of the PG is regulated by various neuropeptides. In the silkworm Bombyx mori, these neuropeptides utilize both hormonal and neuronal pathways to regulate the activity of the PG, making the insect an excellent model system to investigate the complex signaling network controlling ecdysteroid biosynthesis. Here we report another group of neuropeptides, orcokinins, as neuronal prothoracicotropic factors. Using direct mass spectrometric profiling of the axons associated with the PG, we detected several peptide peaks which correspond to orcokinin gene products in addition to the previously described Bommo-FMRFamides (BRFas). In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry revealed that orcokinins are produced in the prominent neurosecretory cells in the ventral ganglia, as well as in numerous small neurons throughout the central nervous system and in midgut endocrine cells. One of the two pairs of BRFa-expressing neurosecretory cells in the prothoracic ganglion coexpresses orcokinin, and these neurons project axons through the transverse nerve and terminate on the surface of the PG. Using an in vitro PG bioassay, we show that orcokinins have a clear prothoracicotropic activity and are able to cancel the static effect of BRFas on ecdysteroid biosynthesis, whereas the suppressive effect of BRFas on cAMP production remained unchanged in the presence of orcokinins. The discovery of a second regulator of PG activity in these neurons further illustrates the potential importance of the PG innervation in the regulation of insect development.

Keywords: ecdysone, prothoracicotropic hormone, prothoracic gland, FMRFamide, direct mass spectrometry

Insects are an ideal model system for studying how the regulatory mechanisms of developmental timing are coordinated with growth. The developmental transitions of insects (i.e., molting and metamorphosis) are strictly regulated by the steroid hormones known as ecdysteroids. The biosynthesis of ecdysteroids, referred to as ecdysteroidogenesis, occurs predominantly in the prothoracic gland (PG) (Gilbert et al., 2002). The activity of the PG is regulated by various neuropeptides including the prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH), which is produced in cerebral neurosecretory cells (Ishizaki and Suzuki, 1994; Gilbert et al., 2002; Marchal et al., 2010). The loss of PTTH in Drosophila melanogaster, for example, leads to a delay in metamorphosis due to a low ecdysteroid titer, and the extended feeding period gives rise to bigger pupae and adults (McBrayer et al., 2007; Rewitz et al., 2009b). Identification of the regulators of the PG activity and investigation of their functions are thus important for understanding the regulatory mechanisms of growth and developmental timing in insects. Such studies may also shed light on the developmental transition mechanisms of metazoans in general.

The silkworm Bombyx mori, being a large lepidopteran insect, is an excellent model organism for neuropeptide research (Yamanaka et al., 2008; Roller et al., 2008). Using this model insect, we have previously characterized several neuropeptide regulators of the PG activity other than PTTH: prothoracicostatic peptides, Bommo-myosuppressin, and Bommo-FMRFamides (BRFas) (Hua et al., 1999; Yamanaka et al., 2005, 2006, 2007, 2010). Of particular interest are BRFas, which are produced by neurons regulating the cAMP production and ecdysteroidogenesis in the PG by direct innervation, whereas the other neuropeptides seem to act on the PG as hormones (Yamanaka et al., 2006; Truman, 2006; Marchal et al., 2010). Bombyx thus utilizes both neuronal and hormonal pathways to regulate ecdysteroidogenesis. This dual control mechanism makes Bombyx a particularly attractive insect for studying ecdysteroidogenesis, especially in terms of investigating how distinct environmental and internal cues for developmental transition are translated into activity of the PG at the molecular level.

Here we report the identification of the neuropeptide orcokinins as neuronal prothoracicotropic factors in Bombyx. Orcokinin was originally isolated from the nervous system of the spinycheek crayfish Orconectes limosus as a myostimulatory factor (Stangier et al., 1992). Orcokinin-like peptides have subsequently been identified in several insects (Pascual et al., 2004; Hofer et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Christie, 2008; Roller et al., 2008; Clynen and Schoofs, 2009), although their physiological functions remain largely unknown except in a few cases (Hofer and Homberg, 2006). The identification of Bombyx orcokinins as another class of prothoracicotropic factors in the PG-innervating neurons further illustrates the importance of the neuronal regulation of PG activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

Bombyx racial hybrids were fed on the artificial diet Silkmate (Nihon Nosan Kogyo, Yokohama, Japan) at 25°C under a 16L/8D photoperiod and staged after the final larval ecdysis. Most larvae started wandering behavior on day 6 of the last (fifth) instar and pupated on day 10.

Peptide synthesis

Peptides were synthesized on a 9050 Plus PepSynthesizer System (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA) using Fmoc (N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl) chemistry according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The crude synthetic peptides were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to a purity exceeding 95%.

Direct mass spectrometry (direct MS) analysis

Direct MS analysis was performed as previously described (Yamanaka et al., 2006).

Production of antibodies

Details of antibodies used in this study are given in Table 1. The N-terminal octapeptide of Bommo-Orc-I and II with a cysteine residue at its C-terminus (NFDEIDRSC) and the C-terminal nonapeptide of calcitonin (CT)-like diuretic hormone (DH) with a cysteine residue at its N-terminus (CAAANFAGGPamide) were both synthesized. These peptides were conjugated to maleimide-activated bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and injected into mice with an adjuvant, AbISCO-100 (Isconova, Uppsala, Sweden). The titer of antibodies in the blood was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using the immunogen peptides conjugated to maleimide-activated ovalbumin (Pierce) as antigens. Antisera from the immunized mice were heated at 56°C for 30 minutes and partially purified for IgG by salting out with ammonium sulfate.

TABLE 1.

Properties of the Primary Antibodies Used in This Study

| Name | Immunogen peptides | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Orcokinin | NFDEIDRS | Mouse polyclonal |

| CT-like DH | AAANFAGGPamide | Mouse polyclonal |

| FMRFamide | FMRFamide | Guinea pig polyclonal |

Antibody characterization

Specificity of the antisera was confirmed by immunohistochemistry on the central nervous system (CNS) of Bombyx larva combined with in situ hybridization. The results of immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization were all equivalent for orcokinin, CT-like DH, and FMRFamide, except that FMRFamide antibody also labeled the cells that express the other FMRFamide-related peptides. The specificities of all the antibodies were also confirmed by preabsorption with 1 µM of corresponding immunogen peptides (Table 1), which invariably abolished all immunostainings. The orcokinin antibody appears to recognize more cells in the terminal abdominal ganglion (TAG; Supporting Fig. 1) compared to the orcokinin-expressing cells detected by in situ hybridization (Fig. 2E). However, prolonged staining with in situ hybridization revealed low orcokinin expression in these additional immunoreactive neurons in the TAG (Supporting Fig. 2).

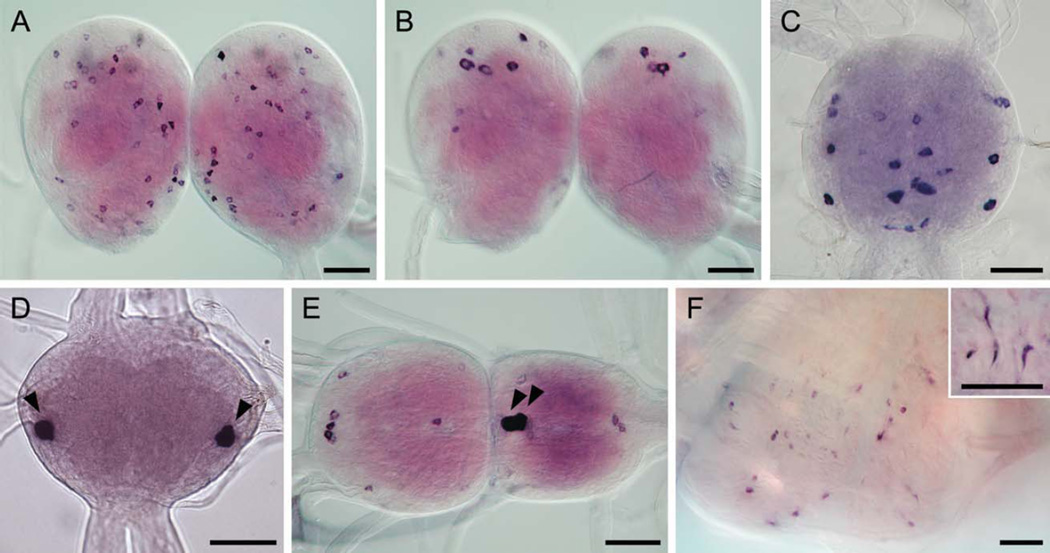

Figure 2.

Orcokinin in situ hybridization. A: Anterior cortex of the brain with numerous small stained neurons. B: Posterior protocerebrum with three pairs of large neurons. C: Subesophageal ganglion showing orcokinin expression in lateral and medial neurons in each of the three neuromeres. D: Mesothoracic ganglion (TG2) showing strong staining in the ventrolateral neurons (arrowheads). E: Terminal abdominal ganglion (TAG) with a pair of posteromedial neurons (arrowheads). The same neurons were also stained in the other abdominal ganglia (AG1-6). F: Endocrine cells in the central midgut region. Inset, a magnified view of the cells with narrow apical cytoplasmic processes. Images are from pharate fifth instar larva (A–E) and fourth instar larva (F). Scale bars = 100 µm.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as previously reported (Roller et al., 2008). Briefly, The 876-bp orcokinin-specific digoxigenin-labeled DNA probe was synthesized by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers as follows: sense primer, 5′-CGATCGCCAACGTCTCTACT-3′; antisense primer, 5′-AACCCTAAACCTCTCTCTCTCC-3′. Dissected tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH7.4), treated with proteinase K (50 µg/mL PBS), and postfixed again with 4% paraformaldehyde before hybridization. After 1–2 hours of prehybridization with hybridization solution (50% formamide, 50 µg/mL heparin, 100 µg/mL salmon testes DNA, 5× SSC and 0.1% Tween 20) at 48°C, hybridization with the DNA probe was performed for 20–24 hours at 48°C. The hybridized tissues were blocked with 1% BSA for 10 minutes and incubated with the alkaline phosphatase-labeled sheep antidigoxigenin (1:1,000; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) overnight at 4°C. Tissues were stained with nitroblue tetrazolium and bromo-chloro-indolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP) solution (Roche) diluted 1:50 in alkaline phosphatase buffer (100 mM Tris, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20; pH 9.5). Stained tissues were either mounted in glycerol and observed under a microscope or further subjected to the immunohistochemical procedure as described below.

Whole-mount immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (Yamanaka et al., 2006; Roller et al., 2008). Briefly, tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight (not applicable for the in situ hybridization-stained samples), blocked with 5% normal goat serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 10 minutes, and incubated with antibodies for 2 days at 4°C. The mouse antibodies against orcokinin and CT-like DH were applied to tissue samples at a dilution of 1:2,000. The guinea pig antiserum to FMRFamide (Grimmelikhuijzen, 1983) was used at a dilution of 1:3,000. The primary antibodies were visualized with Alexa Fluor 555-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-rabbit or antiguinea pig IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; diluted to 1:1,000). The preparations were observed and photographed using a Nikon Eclipse 600 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) or a confocal microscope LSM 510 Meta (Carl Zeiss, Germany) imaging system. The contrast and brightness of the images were modified when necessary using Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Ecdysteroid assay and cAMP assay

The ecdysteroid assay was conducted as described previously (Yamanaka et al., 2005). The cAMP assay was performed essentially as described before (Yamanaka et al., 2005) except using Grace’s Insect Medium (Sigma) as incubation medium instead of Ringer’s solution. The extracted cAMP was quantified with the cAMP-Screen Chemiluminescent Immunoassay System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RESULTS

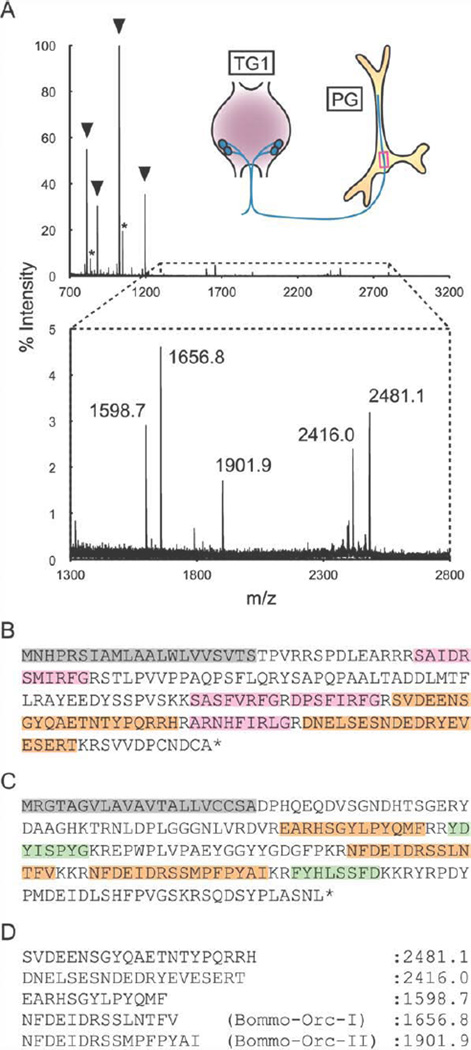

Identification of orcokinins by direct MS of PG-innervating neurons

We have previously used a direct MS technique to detect four BRFa peptides in the axons of PG-innervating neurons (Yamanaka et al., 2006). Closer inspection of the spectra revealed several more peptide signals of larger mass range, albeit much weaker than those of BRFas (Fig. 1A). Two such signals corresponded to peptide fragments from the BRFa precursor flanked by basic amino acid residues (Fig. 1B,D). However, three other signals corresponded to the theoretical masses of peptides predicted to arise from the orcokinin gene product (Fig. 1C,D) (Roller et al., 2008). Among these orcokinin-derived peptides, two were found to contain the conserved N-terminal orcokinin sequence (NFDEIDRS-), which we named Bommo-Orc-I and II (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Direct MS analysis of the PG-innervating axons. A: Illustration shows the anatomical overview of the PG innervation (not to scale), and the red rectangle indicates the piece of the axons applied to the MS analysis. The lower panel is a magnified view of the boxed region of the upper panel. The m/z values of five peaks are shown. Arrowheads indicate the peaks of four BRFa peptides and asterisks denote sodium adducts of two BRFas. B,C: Amino acid sequences of BRFa prepropeptide (B) and orcokinin prepropeptide (C). The signal peptides are highlighted in gray. Four mature BRFas are shown in pink. Five peptide fragments that correspond to the peaks in (A) are highlighted in orange. Two additional putative mature peptides from the orcokinin precursor used in the in vitro assays are given in green. The peptides with C-terminal glycine residues are thought to be amidated. D: Theoretical monoisotopic masses of the five peptide fragments highlighted in orange in (B,C).

Orcokinins are brain-gut peptides

Our MS data prompted us to examine the expression pattern of orcokinin in Bombyx larva. In situ hybridization revealed numerous neurons expressing orcokinin throughout the CNS (Fig. 2A–E). In the head, transcripts for orcokinin were localized in about 60 and 20 somata in the brain and subesophageal ganglion, respectively (Fig. 2A–C). In the ventral ganglia, the maximum level of orcokinin expression was observed in paired ventrolateral neurons in the prothoracic and mesothoracic ganglia (TG1 and 2; Fig. 2D) and in posteromedial neurons in the abdominal neuromeres 1–7 (AG1–7; Fig. 2E). In addition, several paired ventral somata showed weak expression in each thoracic and abdominal ganglion. Transcripts for orcokinin were also detected in endocrine cells (closed and open types) individually scattered throughout the anterior and central midgut (Fig. 2F). In situ hybridization with a sense probe did not show any specific staining (data not shown).

To visualize projections of orcokinin-expressing neurons, we generated an orcokinin antibody. Immunohistochemical analysis in the larval CNS revealed the thoracic ventrolateral neurosecretory cells (NS-VTL1) and the abdominal posteromedial neurosecretory cells (NS-M) projecting into the next posterior transverse nerve (TN; Supporting Fig. 1).

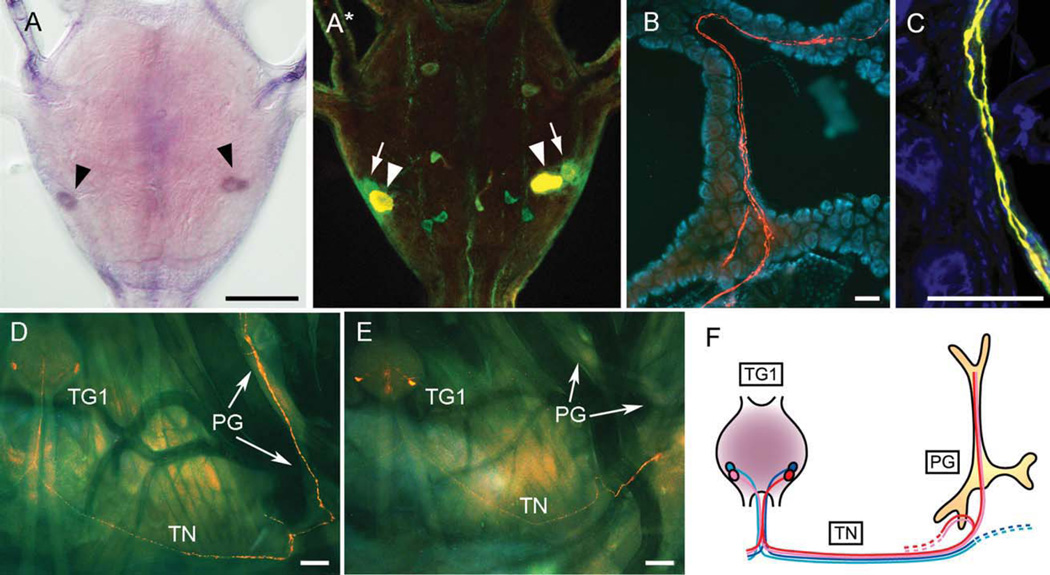

Orcokinins are produced in the PG-innervating BRFa neurons

The expression of orcokinin in one pair of the BRFa neurons (NS-VTL1) of the TG1 is consistent with the detection of orcokinin peptides in the PG surface axons (Fig. 1) (Yamanaka et al., 2006). Indeed, BRFa/orcokinin coexpression in NS-VTL1 was confirmed by double-immunohistochemistry along with in situ hybridization analysis (Fig. 3A). Orcokinin immunostaining also clearly stained the axons that run through the TN to the surface of the PG (Fig. 3B–D). Interestingly, despite the fact that orcokinins are produced only in one of the two pairs of the BRFa neurons in the TG1, the orcokinin antibody stained both of the two BRFa-immunoreactive axons on the PG (Fig. 3C). This result suggests that orcokinin/BRFa-producing NS-VTL1 are the only PG-innervating neurons in the TG1, prompting us to investigate the innervation patterns of the other BRFa neurons (NS-VTL2). We recently found that NS-VTL2 express CT-like DH, along with BRFa and CCHamide (Roller et al., 2008, and data not shown). The immunohistochemistry with CT-like DH antibody was therefore performed to visualize the innervation pattern of NS-VTL2. Axons of both NS-VTL1,2 exit the TG1 via medial nerve and bifurcate extended processes along the TN as described in Manduca (Wall and Taghert, 1991) but terminate in different areas in the periphery (Fig. 3D,E). Axons of NS-VTL1 neurons form a loop around longitudinal or spiracular tracheal trunks as clearly shown in the axons from the TG2 (Supporting Fig. 1B). Axonal processes of NS-VTL1 in TG1 probably bifurcate in the TN near the prothoracic spiracle and give rise to branches with many neurohemal varicosities. Two main branches terminate on the PG surface and the other two branches project back to the proximal part of TN (Fig. 3D). In contrast, axonal projections of NS-VTL2 terminate in the vicinity of the prothoracic spiracle, but do not innervate the PG (Fig. 3E). This result is also consistent with the absence of peaks corresponding to CT-like DH or CCHamide in the direct MS profile (Fig. 1A). Taken together, we conclude that NS-VTL1 producing orcokinins and BRFas are the only peptidergic neurons innervating the PG from the TG1 (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Orcokinin production in the PG-innervating BRFa neurons. A,A*: In situ hybridization of the TG1 with orcokinin probe (A, arrowheads) followed by immunohistochemical double staining of the same ganglion with FMRFamide antibody (green) and orcokinin antibody (red, which looks yellow when colocalized with green, A*). Orcokinin-producing NS-VTL1 are indicated by arrowheads and NS-VTL2 are highlighted by arrows. These FMRFamide-immunoreactive neurons do not express any other known Bombyx FMRFamide-related peptides according to our in situ hybridization analyses (Roller et al., 2008, and data not shown). B: Orcokinin-immunoreactive axons (red) on the surface of the PG. DAPI nuclear staining (blue) shows large nuclei of the PG cells. C: Colocalization (yellow) of the orcokinin (red) and FMRFamide (green) immunoreactivities in the NS-VTL1 axons on the PG counterstained with DAPI (blue). D: Innervation pattern of NS-VTL1 visualized with orcokinin antibody. E: Innervation pattern of NS-VTL2 visualized with CT-like DH antibody. F: Schematic illustration of the differential innervation patterns of the two pairs of the BRFa neurons in the TG1. The orcokinin-producing NS-VTL1 (red) bifurcate and send their axons both ipsilaterally and contralaterally through the transverse nerve (TN) to the surface of the PG. CT-like DH-producing NS-VTL2 (blue) show a similar axonal projections but do not reach to the surface of the PG. Images are from feeding fifth instar larva (A–C) and fourth instar larva (D,E). BRFa and orcokinin-immunoreactive cells in the TG1 were also observed in spinning larvae and throughout pupal stages (data not shown). Scale bars = 100 µm.

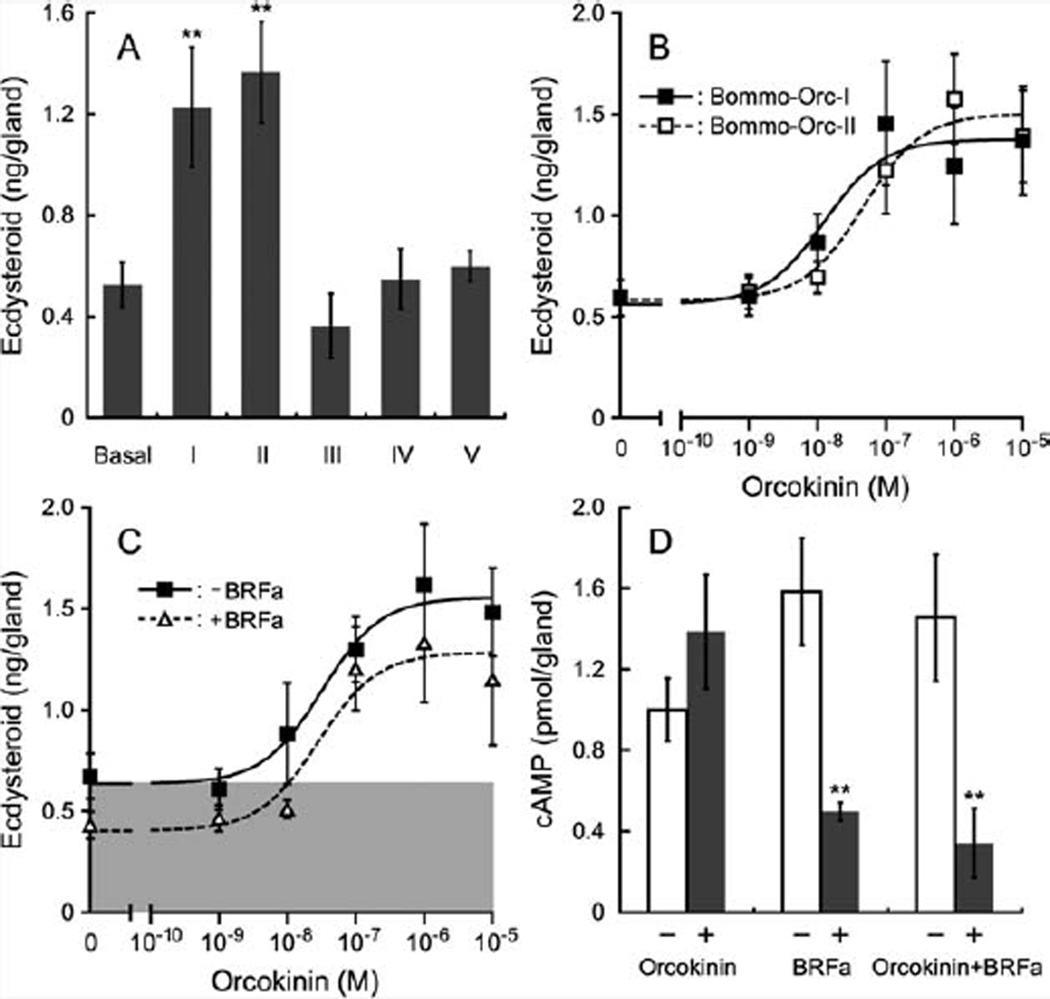

Orcokinins have a prothoracicotropic activity

Having confirmed that orcokinins are produced in PG-innervating neurons, we next investigated their activity on the PG. Based on the direct mass spectra and putative posttranslational processing sites in the precursor, five peptides were synthesized for the in vitro assay (Fig. 1C). Among these peptides, only Bommo-Orc I and II showed a clear prothoracicotropic activity in the ecdysteroid assay using in vitro PG culture (Fig. 4A), suggesting that their conserved sequence at the N termini is responsible for this activity. Bommo-Orc I and II stimulated ecdysteroidogenesis in a dose-dependent manner, with EC50 values of 12.6 and 46.8 nM, respectively (Fig. 4B). Although this activity is much weaker than PTTH, the effective concentrations of orcokinins are lower than BRFas, which are only effective at micromolar concentrations (Yamanaka et al., 2006). As discussed in our previous work (Yamanaka et al., 2006), because these neuronal regulators of PG activity are released directly onto the surface of the gland, their local concentrations can be much higher than hormones like PTTH. Indeed, orcokinins at a concentration of 10 −7 M was sufficient to completely reverse the prothoracicostatic activity of 10 −5 M BRFas (Fig. 4C). This result clearly demonstrates the importance of orcokinins as co-mediators of the regulatory activity in these neurons. Interestingly, this antagonistic effect of orcokinins was not detected at the cAMP level, where even 10 −5 M orcokinins showed no effect on the static effect of 10 −5 M BRFas (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Prothoracicotropic activities of orcokinins in vitro. A: Ecdysteroidogenic activities of five peptides from the orcokinin precursor. Day-4 fifth-instar larval PGs were incubated with 10 −5 M of orcokinin peptides. Basal, no peptide; I, Bommo-Orc-I; II, Bommo-Orc-II; III, EARHSGYLPYQMF; IV, YDYISPYamide; V, FYHLSSFD. n = 7–8. Error bars indicate SEM. **P < 0.01. B: Dose–response relationship of the two ecdysteroidogenic orcokinins. Day-4 fifth-instar larval PGs were incubated with various amounts of each orcokinin. n = 7–8. Error bars indicate SEM. C: Effect of BRFa on the prothoracicotropic activity of orcokinins. Day-4 fifth-instar larval PGs were incubated with various amounts of a mixture of two prothoracicotropic orcokinins (equal amount of Bommo-Orc-I and II; total concentrations of the two peptides are indicated), either in the absence or presence of 10−5 M BRFa mixture (2.5 × 10−6 M each of four BRFas). Although BRFas shifted the dose-response curve of orcokinins downward, 10−7 M of orcokinins was sufficient to stimulate ecdysteroidogenesis above the basal level (indicated by shaded area) even in the presence of BRFas. n = 7–8. Error bars indicate SEM. D: cAMP assay. Day-4 fifth-instar larval PGs were incubated either without (open bars) or with (filled bars) 10−5 M orcokinin mixture (5.0 × 10−6 M each of Bommo-Orc-I and II) and/or 10−5 M BRFa mixture. n = 4. Error bars indicate SEM. **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Bombyx orcokinins are neuronal prothoracicotropic factors

Different insects seem to use distinct signaling networks to control ecdysteroidogenesis. For example, we have previously shown that the PG-innervating neurons in Bombyx produce prothoracicostatic factors named BRFas, and these neurons appear to downregulate the expression of some ecdysteroidogenic enzymes during development (Yamanaka et al., 2006, 2007). By contrast, the only PG-innervating neurons in Drosophila produce PTTH, which functions as a hormone in many other insects, to upregulate ecdysteroidogenesis (Siegmund and Korge, 2001; McBrayer et al., 2007). Positive regulation of ecdysteroidogenesis by direct innervation of the PG has also been reported in the American cockroach (Richter and Gersch, 1983; Richter and Bohm, 1997). These reports from different insects clearly indicate a more complex role of the innervation of the PG than initially thought. Indeed, these findings even suggest interplay between multiple factors within a given set of PG-innervating neurons of the same species.

Here we identified neuropeptides named orcokinins in Bombyx as a second neuronal regulator of ecdysteroidogenesis. To our surprise, orcokinins have a clear prothoracicotropic activity contrary to BRFas, which are produced in the same PG-innervating neurons (Fig. 3). The signals that correspond to orcokinins in direct MS profiles were weaker than those of BRFas (Fig. 1A), but this is probably caused by reduced sensitivity of the technique for larger peptide fragments (Wegener et al., 2006). Moreover, the ecdysteroid assay using in vitro PG cultures suggests lower effective concentrations of orcokinins than those of BRFas (Fig. 4). Combined with the clear immunohistochemical staining of orcokinins (Fig. 3), we conclude that this class of peptides is involved in the neural regulation of ecdysteroidogenesis together with BRFas.

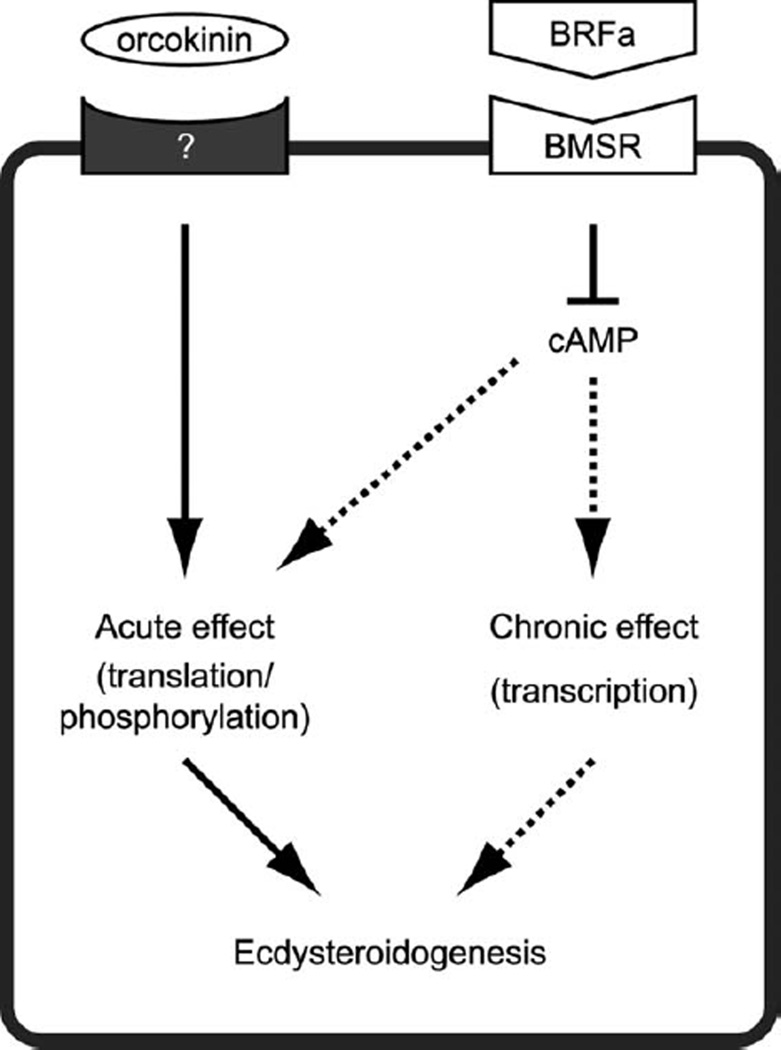

What is the role of orcokinins in this regulatory pathway? Although the prothoracicotropic effect of orcokinins was strong enough to reverse the prothoracicostatic effect of BRFas at the level of secreted amounts of ecdysteroids, the inhibitory effect of BRFas on the production of cAMP persisted even in the presence of orcokinins (Fig. 4). Therefore, the prothoracicotropic effect of orcokinins, which becomes manifest during short-term in vitro incubation of the PG, is mediated by a cAMP-independent pathway (Fig. 5). At the molecular level, such an acute regulation of ecdysteroidogenesis is mainly mediated by translation and phosphorylation of the molecules involved in ecdysteroidogenesis (Gilbert et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2008; Rewitz et al., 2009a). On the other hand, a cAMP-mediated pathway is also involved in the transcriptional regulation of some genes encoding ecdysteroidogenic enzymes, most likely mediated by Protein kinase A (Gilbert et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2008) and pharmacologically separable from the acute regulation of ecdysteroidogenesis (Yamanaka et al., 2007). Orcokinins might specifically eliminate the acute prothoracicostatic effect of BRFas while maintaining the chronic inhibitory effect of BRFas on ecdysteroidogenesis (Fig. 5). This is consistent with our previous observation that the expression levels of some ecdysteroidogenic enzymes seem to be negatively regulated by the PG-innervating neurons (Yamanaka et al., 2007).

Figure 5.

Model for the mode of action of two neuronal regulators of ecdysteroidogenesis. BRFa activates the Bommo-myosuppressin receptor (BMSR) expressed in the PG. The activated BMSR inhibits the production of cAMP, which is involved both in the acute and chronic regulation of ecdysteroidogenesis. Orcokinin activates an as-yet-unknown orcokinin receptor, which in turn exerts an acute effect on ecdysteroidogenesis via a cAMP-independent pathway.

What is the functional significance of such a complex feature of the Bombyx PG-innervating neurons? It is known that a low level of ecdysteroid titer during the intermolt period has a complex effect on the regulation of tissue growth and proliferation (Champlin and Truman, 1998; Nijhout and Grunert, 2002; Colombani et al., 2005; Nijhout et al., 2007). Therefore, orcokinins might maintain a low ecdysteroid titer while BRFas suppress full potentiation of the gland prior to the ecdysteroid pulse generated by PTTH (Mizoguchi et al., 2001). The counteracting neural inputs might also act during the wandering stage, when BRFas seem to suppress the transcript level of some ecdysteroidogenic enzymes to regulate the timing or duration of the ecdysteroid pulse (Yamanaka et al., 2007). During this period, orcokinins are probably masking the acute static effect of BRFas. In a previous study, the recording of the neural activity was performed on both of the two pairs of the BRFa neurons in the TG1 (Yamanaka et al., 2006). Because we now know that only one out of these two pairs of BRFa neurons innervates the PG, more refined analysis of the firing activity of these neurons is required to investigate the above possibilities.

The molecular identity of the orcokinin receptor is unknown. We have tested all the neuropeptide G protein-coupled receptors significantly expressed in the PG (Yamanaka et al., 2008, 2010) for their putative function as an orcokinin receptor, but none of them responded to any orcokinins in our heterologous expression system (data not shown). This result might indicate that the orcokinin receptor is not a typical neuropeptide GPCR, although we cannot rule out the possibility that the receptor needs cofactor(s) or accessory protein(s) to activate downstream signaling (Johnson et al., 2005; Mertens et al., 2005). Future identification of the orcokinin receptor should provide important information concerning the mode of action of these neuropeptides.

Distribution pattern of orcokinins suggests their role as pleiotropic brain-gut peptides

Although there is growing evidence that orcokinins are present in a variety of insects, cells producing these peptides have only been identified in the brains of the silverfish and three polyneopteran species (Hofer et al., 2005). To our knowledge, this is the first description of the cells expressing orcokinin in a holometabolous (endopterygote) insect. In Bombyx larva, about 190 neurons expressing orcokinin were recognized by in situ hybridization. Subsequent immunohistochemical analysis revealed that these cells include numerous interneurons projecting axons within the CNS and neurosecretory cells in the ventral ganglia. Although fine projections of the former group of neurons could not be traced in the whole-mount preparations, it is evident that orcokinins play a role as neuromodulators and/or cotransmitters within the CNS. Bombyx orcokinin was also expressed in a subpopulation of the endocrine cells in the midgut, but we did not detect orcokinin-immunoreactive fibers in the retrocerebral complex. This latter finding is in contrast to a previous study in dicondylian insects (Hofer et al., 2005). The antibody used in the previous study did not recognize any antigens in the brains of endopterygote species (Hofer et al., 2005), probably due to its specificity against the C-terminal region of the crustacean orcokinin isoform (Bungart et al., 1994). Here we developed a new antiserum directed against the N-terminal region that is well conserved in all known isoforms of orcokinin (NFDEIDRS). We believe this antibody will be useful for studying the distribution of orcokinins in a wide spectrum of arthropods.

In summary, we have identified orcokinins as a second neural regulator of ecdysteroidogenesis in Bombyx. Moreover, the wide distribution of orcokinin-producing cells indicates that these neuropeptides possess multiple functions. This study provides a solid basis for studying pleiotropic actions of orcokinins, the elucidation of which may shed light on unexpected features in the development and physiology of a variety of arthropod species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Grant number: Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 21380040 (to Y.T. and A.M.) 19380034 (to H.K.), research fellowship (to N.Y.); Grant sponsor: Biooriented Technology Research Advancement Institution (Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences to H.K.); Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: GM 67310; Grant sponsor: Slovak grant agencies; Grant numbers: VEGA2/0132/09, APVV-51-039105 and SAV-FM-EHP-2008-02-06.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bungart D, Dircksen H, Keller R. Quantitative determination and distribution of the myotropic neuropeptide orcokinin in the nervous system of astacidean crustaceans. Peptides. 1994;15:393–400. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(94)90194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champlin DT, Truman JW. Ecdysteroids govern two phases of eye development during metamorphosis of the moth, Manduca sexta. Development. 1998;125:2009–2018. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie AE. In silico analyses of peptide paracrines/hormones in Aphidoidea. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2008;159:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clynen E, Schoofs L. Peptidomic survey of the locust neuroendocrine system. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39:491–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombani J, Bianchini L, Layalle S, Pondeville E, Dauphin-Villemant C, Antoniewski C, Carre C, Noselli S, Leopold P. Antagonistic actions of ecdysone and insulins determine final size in Drosophila. Science. 2005;310:667–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1119432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LI, Rybczynski R, Warren JT. Control and biochemical nature of the ecdysteroidogenic pathway. Annu Rev Entomol. 2002;47:883–916. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmelikhuijzen CJ. FMRFamide immunoreactivity is generally occurring in the nervous systems of coelenterates. Histochemistry. 1983;78:361–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00496623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer S, Homberg U. Evidence for a role of orcokinin-related peptides in the circadian clock controlling locomotor activity of the cockroach Leucophaea maderae. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:2794–2803. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer S, Dircksen H, Tollback P, Homberg U. Novel insect orcokinins: characterization and neuronal distribution in the brains of selected dicondylian insects. J Comp Neurol. 2005;490:57–71. doi: 10.1002/cne.20650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua YJ, Tanaka Y, Nakamura K, Sakakibara M, Nagata S, Kataoka H. Identification of a prothoracicostatic peptide in the larval brain of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31169–31173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Warren JT, Gilbert LI. New players in the regulation of ecdysone biosynthesis. J Genet Genomics. 2008;35:1–10. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki H, Suzuki A. The brain secretory peptides that control moulting and metamorphosis of the silkmoth, Bombyx mori. Int J Dev Biol. 1994;38:301–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EC, Shafer OT, Trigg JS, Park J, Schooley DA, Dow JA, Taghert PH. A novel diuretic hormone receptor in Drosophila: evidence for conservation of CGRP signaling. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1239–1246. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Baggerman G, D’Hertog W, Verleyen P, Schoofs L, Wets G. In silico identification of new secretory peptide genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:510–522. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400114-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal E, Vandersmissen HP, Badisco L, Van de Velde S, Verlinden H, Iga M, Van Wielendaele P, Huybrechts R, Simonet G, Smagghe G, Vanden Broeck J. Control of ecdysteroidogenesis in prothoracic glands of insects: a review. Peptides. 2010;31:506–519. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBrayer Z, Ono H, Shimell M, Parvy JP, Beckstead RB, Warren JT, Thummel CS, Dauphin-Villemant C, Gilbert LI, O’Connor MB. Prothoracicotropic hormone regulates developmental timing and body size in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2007;13:857–871. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens I, Vandingenen A, Johnson EC, Shafer OT, Li W, Trigg JS, De Loof A, Schoofs L, Taghert PH. PDF receptor signaling in Drosophila contributes to both circadian and geotactic behaviors. Neuron. 2005;48:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi A, Ohashi Y, Hosoda K, Ishibashi J, Kataoka H. Developmental profile of the changes in the prothoracicotropic hormone titer in hemolymph of the silkworm Bombyx mori: correlation with ecdysteroid secretion. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;31:349–358. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(00)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout HF, Grunert LW. Bombyxin is a growth factor for wing imaginal disks in Lepidoptera. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15446–15450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242548399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout HF, Smith WA, Schachar I, Subramanian S, Tobler A, Grunert LW. The control of growth and differentiation of the wing imaginal disks of Manduca sexta. Dev Biol. 2007;302:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual N, Castresana J, Valero ML, Andreu D, Belles X. Orcokinins in insects and other invertebrates. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:1141–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewitz KF, Larsen MR, Lobner-Olesen A, Rybczynski R, O’Connor MB, Gilbert LI. A phosphoproteomics approach to elucidate neuropeptide signal transduction controlling insect metamorphosis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009a;39:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewitz KF, Yamanaka N, Gilbert LI, O’Connor MB. The insect neuropeptide PTTH activates receptor tyrosine kinase torso to initiate metamorphosis. Science. 2009b;326:1403–1405. doi: 10.1126/science.1176450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter K, Bohm GA. The molting gland of the cockroach Periplaneta americana: secretory activity and its regulation. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;29:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00521-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter K, Gersch M. Electrophysiological evidence of nervous involvement in the control of the prothoracic gland in Periplaneta americana. Experientia. 1983;39:917–918. [Google Scholar]

- Roller L, Yamanaka N, Watanabe K, Daubnerova I, Zitnan D, Kataoka H, Tanaka Y. The unique evolution of neuropeptide genes in the silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:1147–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund T, Korge G. Innervation of the ring gland of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 2001;431:481–491. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010319)431:4<481::aid-cne1084>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangier J, Hilbich C, Burdzik S, Keller R. Orcokinin: a novel myotropic peptide from the nervous system of the crayfish, Orconectes limosus. Peptides. 1992;13:859–864. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(92)90041-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truman JW. Steroid hormone secretion in insects comes of age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8909–8910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603252103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall JB, Taghert PH. Segment-specific modifications of a neuropeptide phenotype in embryonic neurons of the moth, Manduca sexta. J Comp Neurol. 1991;309:375–390. doi: 10.1002/cne.903090307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener C, Reinl T, Jansch L, Predel R. Direct mass spectrometric peptide profiling and fragmentation of larval peptide hormone release sites in Drosophila melanogaster reveals tagma-specific peptide expression and differential processing. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1362–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N, Hua YJ, Mizoguchi A, Watanabe K, Niwa R, Tanaka Y, Kataoka H. Identification of a novel prothoracicostatic hormone and its receptor in the silkworm Bombyx mori. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14684–14690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N, Zitnan D, Kim YJ, Adams ME, Hua YJ, Suzuki Y, Suzuki M, Suzuki A, Satake H, Mizoguchi A, Asaoka K, Tanaka Y, Kataoka H. Regulation of insect steroid hormone biosynthesis by innervating peptidergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8622–8627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511196103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N, Honda N, Osato N, Niwa R, Mizoguchi A, Kataoka H. Differential regulation of ecdysteroidogenic P450 gene expression in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71:2808–2814. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N, Yamamoto S, Zitnan D, Watanabe K, Kawada T, Satake H, Kaneko Y, Hiruma K, Tanaka Y, Shinoda T, Kataoka H. Neuropeptide receptor transcriptome reveals unidentified neuroendocrine pathways. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N, Hua YJ, Roller L, Spalovska-Valachova I, Mizoguchi A, Kataoka H, Tanaka Y. Bombyx prothoracicostatic peptides activate the sex peptide receptor to regulate ecdysteroid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2060–2065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907471107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.