ABSTRAT

We recently performed 2 studies viewing the presence of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPVs) types 16, 18, 31, 33 and 35 in human breast cancer in the Syrian population. Herein, we report that EBV and high-risk HPVs are co-present in breast cancer in Syrian women. Therefore, and based on our previous studies and present data, we reveal that 35 (32%) of 108 cancer samples are positive for both EBV and high-risk HPVs and their co-presence is associated with high grade invasive ductal carcinomas (IDCs) with at least one positive lymph nodes, in comparison with EBV and high-risk HPVs-positive samples, which are low to intermediate grade IDCs, respectively. Future studies are needed to confirm the co-presence and the cooperation effect of these onco-viruses in human breast carcinogenesis and metastasis.

KEYWORDS: breast cancer, cancer phenotype, EBV, high-risk HPV, Syrian women

Breast cancer is the most frequent cause of cancer-related death among women. According to the World Health Organization more than 508,000 deaths have been attributed to breast cancer in 2011 (Global Health Estimates, WHO 2013). Actually, it is well known that the majority of cancer deaths are the result of metastasis, either directly due to tumor involvement of critical organs or indirectly due to therapeutic resistance and the inability of available therapy to control tumor progression. It is estimated that approximately 20% of human cancers could be linked to virus infection including Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPV) especially types 16, 18 and 33, which cumulatively infect 80-90% of the population worldwide.1,2 Accordingly, we have recently explored the presence of EBV in a cohort of 108 breast cancer samples from Syrian women by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis using specific primers for LMP1 and EBNA1 genes of EBV and a monoclonal anybody for LMP1. In this context, it is important to mention that PCR and IHC were largely used to detect the presence of onco-viruses, particularly EBV and HPVs, in human cancers.1,2 Our study revealed that 56 (51.85%) of the 108 samples are EBV positive. Additionally, we reported that the LMP1 expression is correlated with invasive breast cancer phenotype in more than 60% of breast cancer samples as opposed to ∼20% of in-situ cancer tissues.3 Several other recent studies, including 3 from the Middle East, showed clearly that EBV is present in 30-50% of human breast cancer.4-8 Overall, these studies demonstrate that EBV is present in human breast cancer; given the biological actions of EBV-derived onco-proteins, it is quite possible that it plays an important role in the initiation and/or progression of this malignancy. This is based on our study as well as recent investigations about the role of LMP1 and EBNA1 onco-proteins of EBV in the initiation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in human nasopharyngeal cancer.9,10

On the other hand, it was pointed out that high-risk HPVs, especially types 16, 18 and 33, can also be found in human breast cancer;2 however, their precise role is not clear. Therefore, we explored the role of E6/E7 onco-proteins of high-risk HPV type 16, which is the most frequent HPV type worldwide. We reported that the E6/E7 of HPV type 16 virus converts non-invasive and non-metastatic breast cancer cells to an invasive and metastatic phenotype; this was accompanied by an overexpression of Id-1 gene,11 which is an important regulator of cell invasion.12 Furthermore, we showed that E6/E7 onco-proteins up-regulate Id-1 promoter activity in these breast cancer cells. In parallel, we found that HPV type 16 is present in all examined invasive and metastatic breast cancer samples, from Canadian women, and less frequently in in situ breast cancer as opposed to normal mammary tissue.11 Therefore and based on this investigation, we explored the incidence of high risk HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33 and 35 in a cohort of 113 breast cancer samples from Syrian women by PCR and tissue microarray analysis. Our study revealed that 69 (61.06%) of the 113 samples are HPV positive, while 24 (34.78%) of them are co-infected with more than one HPV type. Additionally, we showed that the expression of the E6 onco-protein of high-risk HPVs is correlated with Id-1 overexpression in the majority of invasive breast cancer tissue samples.13 Earlier studies reported that high-risk HPVs, especially types 16,18 and 33, are present in human breast cancer worldwide including the Middle East area, and their presences are correlated with more aggressive phenotypes.2,14 However, the presence of high-risk HPVs in human breast cancer is still a subject of controversy since some investigations were unable to detect HPVs in breast cancer as well as normal mammary tissues.15,16

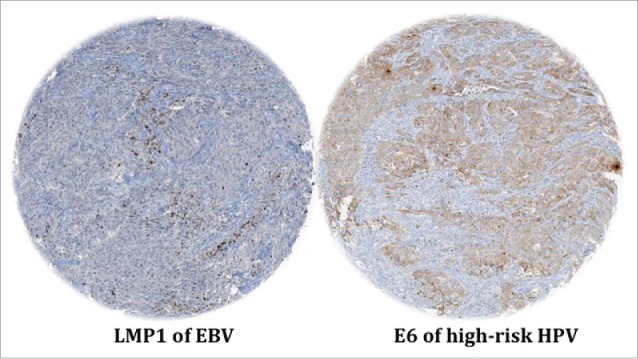

In this study, we explored the presence of EBV and high-risk HPV (types 16, 18, 31, 33 and 35) together in breast cancer in Syrian women by PCR and tissue microarray methodologies using specific primers and monoclonal antibodies with all the necessary controls, as described previously by our group.3,11,13 The use of these specimens and data in research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Aleppo University.3,13 We report that 35 (32%) of the 108 samples are positive for both EBV and high-risk HPVs (Table 1A). Based on these data and our 2 earlier studies, we assessed the association between the co-presence of these viruses and tumor aggressiveness in our samples. We reveal that the co-expression of the LMP1 and E6 onco-proteins of EBV and high-risk HPVs, respectively, is associated with grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) phenotypes (Table 1B and Fig. 1) with one or more positive lymph nodes, in comparison with positive cases of EBV alone or HPVs alone as well as negatives cases for both, EBV and HPVs.3,11,13 while, it is important to mention that EBV and HPVs positive cases were found to be low to intermediate grade IDC, respectively. In parallel, normal mammary tissue and epithelial cells, which were used as controls, were revealed negative for both EBV and HPVs.3,11,13

Table 1B.

Presence of EBV and high-risk HPVs and their associations with high-grade invasive ductal carcinomas. The co-presence of EBV and high-risk HPVs is associated with grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma and one or more positive lymph nodes but not with In Situ breast cancer tissues (P = 0.0013). While, it is important to highlight that EBV and HPVs positive cases were found to be low to intermediate IDC, respectively. On the other hand, the co-presence of EBV and high-risk HPVs was assessed by PCR for LMP1 and EBNA1 and E6/E7 genes and confirmed by IHC analysis of LMP1 and E6 expression using Tissue Microarray (TMA) methodology, as illustrated by our team;3,11,13 Two cores for TMA and 4 cores for DNA extraction and PCR analysis were used from each samples; Normal mammary epithelial cells and EBV and high-risk HPV-infected cells were employed as negative and positive controls in our analysis.3,13

High grade Invasive ductal carcinomas

EBV+ alone or HPVs+ alone are low to intermediate grade Invasive ductal carcinomas

Table 1A.

EBV and high-risk HPVs detection in human breast carcinomas. The co-incidence of these viruses was found in 35 (32%) samples out of 108 examined by PCR and IHC using specific primers for LMP1, EBNA1 and E6/E7 genes of EBV and high-risk HPVs types (16, 18, 31, 33 and 35) as well as monoclonal antibodies for E6 and LMP1, as described by our group.3,11,13 On the other hand, we noted that EBV alone and high-risk HPVs alone are present in 56 and 66 of our samples, respectively. The source of our samples is the pathology department of the Faculty of Medicine of Aleppo University. These samples are collected from 2000 to 2007, and they were chosen based on the pathology report, as breast cancer cases. All the samples are paraffin embedded tissue blocks stored at the pathology department.

| Tested cases | Detection method | EBV+ & HPVs+ | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Paraffin samples) | 108 | PCR/IHC* | 35 | 32 |

These 2 methodologies, PCR and IHC, were used to detect the presences of EBV and high-risk HPVs.

Figure 1.

Representative IHC revealing LMP1 and E6 expression of EBV and high-risk HPVs, respectively, in the same breast cancer sample which is high grade invasive ductal carcinoma. Magnification is 100X. This analysis was performed using TMA methodology with all the necessary controls. Co-presence of EBV and high-risk HPVs was confirmed by PCR using specific primers for LMP1, EBNA1 and E6/E7 genes.3,11,13

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first report on the co-presence of EBV and high-risk HPVs in human breast cancer and the relation of this co-incidence with cancer phenotype in the Middle East area using 2 methodologies, PCR and IHC (Table 1A and 1B). In fact, there are only 6 investigations worldwide regarding the co-presence of EBV and high-risk HPVs in human breast cancer: one from Australia,7 one from Chile,17 one from China,18 2 from Taiwan19,20 and one from the USA.21 Five among these studies confirmed the presence of both EBV and HPVs in breast cancer using mainly PCR analysis;7,17,18,19,20 however one study could not confirm this statement in which the authors used RNA-Sequencing analysis to detect the presence of these viruses.21 The presences of these viruses vary from 2% to approximately 50% in breast cancer with far lower frequency in benign and normal mammary tissues. Regarding the relation between the presence of these viruses and histopathological parameters as well as survival, 2 studies found that the presence of EBV and HPVs could enhance the grade of breast cancer and relapse-free survivals of cancer patients.7,20 In our study, we demonstrated that the co-presence of EBV and high-risk HPVs is associated with high-grade invasive ductal carcinomas, with one or more positive lymph nodes, in the Syrian women. We believe that LMP1 and/or EBNA1 genes of EBV could cooperate with E5 and E6/E7 genes of high-risk HPVs to transform human mammary epithelial cell and consequently initiate cancer development and ultimately cancer metastasis via the EMT event, as mentioned above and suggested in human oral cancer by our group;22 this hypothesis is under investigation by our group. However, we consider that further studies are necessary to elucidate the role and pathogenesis of the co-presence of EBV and HPVs in human breast malignancy; especially since EBV vaccine and second-generation HPVs vaccine (nonavalent vaccine)23 are presently under clinical trial studies and available, respectively. Therefore, it is of great interest to gain a better understanding of the association between EBV and HPVs co-infection and breast cancer initiation and progression. This great advancement could potentially limit breast cancer initiation as well as its progression to a metastatic form thereby decreasing cancer-related deaths. Ultimately, these data suggest that, for at least some populations, breast cancer incidence and biology could be eventually altered using public health programs that include antiviral vaccines and therapies.

Finally, it is important to highlight that our investigation, in the Syrian population, is limited to a small number of cases located in a single region of Syria; therefore, it is essential to perform other studies of large number of cases from different regions of this country and ultimately several studies from the Middle-East in general.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mrs. A. Kassab for her critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) and the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ- Réseau du Cancer). The new research lab of Dr. Al Moustafa is supported by the College of Medicine at Qatar University.

References

- [1].Saha A, Kaul R, Murakami M, Robertson ES. Tumor viruses and cancer biology: Modulating signaling pathways for therapeutic intervention. Cancer Biol Ther 2010; 10:961-78; PMID:21084867; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cbt.10.10.13923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Al Moustafa A-E. Role of high-risk human papillomaviruses in breast carcinogenesis In: Gupta SP, editor. Breast Carcinogenesis; Oncoviruses and Their Inhibitors, Boca Raton: CRC, Taylor and Francis Group; 2014. p. 245-62. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Aboulkassim T, Yasmeen A, Akil N, Batist G, Al Moustafa AE. Incidence of Epstein-Barr virus in Syrian women with breast cancer: A tissue microarray study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015;11:951-5; PMID:25933186; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/21645515.2015.1009342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kalkan A, Ozdarendeli A, Bulut Y, Yekeler H, Cobanoglu B, Doymaz MZ. Investigation of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in formalin-fixed and paraffin- embedded breast cancer tissues. Med Princ Pract 2005; 14:268-71; PMID:15961939; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000085748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lorenzetti MA, De Matteo E, Gass H, Martinez Vazquez P, Lara J, Gonzalez P, Preciado MV, Chabay PA. Characterization of Epstein Barr virus latency pattern in Argentine breast carcinoma. PLoS One 2010; 5:e13603; PMID:21042577; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0013603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hachana M, Amara K, Ziadi S, Romdhane E, Gacem RB, Trimeche M. Investigation of Epstein-Barr virus in breast carcinomas in Tunisia. Pathol Res Pract 2011; 207:695-700; PMID:22024152; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.prp.2011.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Glenn WK, Heng B, Delprado W, Iacopetta B, Whitaker NJ, Lawson JS. Epstein-Barr virus, human papillomavirus and mouse mammary tumour virus as multiple viruses in breast cancer. PLoS One 2012; 7:e48788; PMID:23183846; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0048788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zekri AR, Bahnassy AA, Mohamed WS, El-Kassem FA, El-Khalidi SJ, Hafez MM, Hassan ZK. Epstein-Barr virus and breast cancer: epidemiological and molecular study on Egyptian and Iraqi women. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 2012; 24:123-31; PMID:22929918; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jnci.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Horikawa T, Yoshizaki T, Kondo S, Furukawa M, Kaizaki Y, Pagano JS. Epstein-Barr Virus latent membrane protein 1 induces Snail and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2011; 104:1160-7; PMID:21386845; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2011.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wang L, Tian WD, Xu X, Nie B, Lu J, Liu X, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) protein induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cancer 2014; 120:363-72; PMID:24190575; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.28418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yasmeen A, Bismar TA, Kandouz M, Foulkes WD, Desprez PY, Al Moustafa AE. E6/E7 of HPV type 16 promotes cell invasion and metastasis of human breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle 2007; 6:2038-42; PMID:17721085; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.6.16.4555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ling MT, Wang X, Zhang X, Wong YC. The multiple roles of Id-1 in cancer progression. Differentiation 2006; 74:481-7; PMID:17177845; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Akil N, Yasmeen A, Kassab A, Ghabreau L, Darnel AD, Al Moustafa AE.High-risk human papillomavirus infections in breast cancer in Syrian women and their association with Id-1 expression: a tissue microarray study. Br J Cancer 2008; 99:404-7; PMID:18648363; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Al Moustafa AE, Al-Awadhi R, Missaoui N, Adam I, Durusoy R, Ghabreau L, Akil N, Ahmed HG, Yasmeen A, Alsbeih G. Human papillomaviruses-related cancers. Presence and prevention strategies in the Middle east and north African regions. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10:1812-21; PMID:25424787; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.28742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].de Cremoux P, Thioux M, Lebigot I, Sigal-Zafrani B, Salmon R, Sastre-Garau X, Institut Curie Breast Group . No evidence of human papillomavirus DNA sequences in invasive breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008; 109:55-8; PMID:17624590; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10549-007-9626-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hedau S, Kumar U, Hussain S, Shukla S, Pande S, Jain N, Tyagi A, Deshpande T, Bhat D, Mir MM, et al.. Breast cancer and human papillomavirus infection: no evidence of HPV etiology of breast cancer in Indian women. BMC Cancer 2011; 11:27; PMID:21247504; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2407-11-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Aguayo F, Khan N, Koriyama C, González C, Ampuero S, Padilla O, Solís L, Eizuru Y, Corvalán A, Akiba S. Human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus infections in breast cancer from chile. Infect Agent Cancer 2011; 6:7; PMID:21699721; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1750-9378-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Peng J, Wang T, Zhu H, Guo J, Li K, Yao Q, Lv Y, Zhang J, He C, Chen J, et al.. Multiplex PCR/mass spectrometry screening of biological carcinogenic agents in human mammary tumors. J Clin Virol 2014; 61:255-9; PMID:25088618; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tsai JH, Tsai CH, Cheng MH, Lin SJ, Xu FL, Yang CC. Association of viral factors with non-familial breast cancer in Taiwan by comparison with non-cancerous, fibroadenoma, and thyroid tumor tissues. J Med Virol 2005; 75:276-81; PMID:15602723; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jmv.20267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tsai JH, Hsu CS, Tsai CH, Su JM, Liu YT, Cheng MH, Wei JC, Chen FL, Yang CC. Relationship between viral factors, axillary lymph node status and survival in breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2007; 133:13-21; PMID:16865407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00432-006-0141-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Khoury JD, Tannir NM, Williams MD, Chen Y, Yao H, Zhang J, Thompson EJ, TCGA Network, Meric-Bernstam F, Medeiros LJ, et al.. Landscape of DNA virus associations across human malignant cancers: analysis of 3,775 cases using RNA-Seq. J Virol 2013; 87:8916-26; PMID:23740984; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.00340-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Al Moustafa A-E. E5 and E6/E7 of high-risk HPVs cooperate to enhance cancer progression through EMT initiation. Cell Adh Migr 2015; 9(5):392-3; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/19336918.2015.1042197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Riethmuller D, Jacquard AC, Lacau St Guily J, Aubin F, Carcopino X, Pradat P, Dahlab A, Prétet JL. Potential impact of a nonavalent HPV vaccine on the occurrence of HPV-related diseases in France. BMC Public Health 2015; 15:453; PMID:25934423; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/s12889-015-1779-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]