Abstract

Mothers with HIV are at high risk of a range of psychosocial issues that may impact HIV disease progression for themselves and their children. Stigma has also become a substantial barrier to accessing HIV/AIDS care and prevention services. The study objective was to determine the prevalence and severity of postpartum depression (PPD) amongst women living with HIV and to further understand the impact of stigma and other psychosocial factors in 123 women living with HIV attending Prevention of Mother to Child transmission (PMTCT) clinic at Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) located in Nairobi, Kenya. We used the EPDS scale and HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument – PLWHA (HASI – P). Forty-eight percent (N=59) of women screened positive for elevated depressive symptoms. Eleven (9%) of the participants reported high levels of stigma. Multivariate analyses showed that lower education (OR=0.14, 95% CI [0.04 – 0.46], p=0.001) and lack of family support (OR=2.49, 95% CI [1.14 – 5.42], p=0.02) were associated with presence of elevated depressive symptoms. The presence of stigma implied more than 9 fold risk of development of PPD (OR=9.44, 95% CI [1.132–78.79], p=0.04). Stigma was positively correlated with an increase in PPD. PMTCT is an ideal context to reach out to women to address mental health problems especially depression screening and offering psychosocial treatments bolstering quality of life of the mother-baby dyad.

Keywords: Postpartum, Depression, HIV, Stigma, Prevention of Mother–to-Child transmission

Background

Mothers with HIV face a range of psychosocial problems, including postpartum depression (PPD) (Vesga-Lopez, Blanco, Keyes, Olfson, Grant, & Hasin, 2008) which impacts HIV disease progression in the mother and has lasting impacts for child health (Hartley, Pretorius, Mohamed, Laughton, Madhi, Cotton & Seedat, 2010). Depression is a highly prevalent co-morbidity among HIV+ individuals (Owe-Larsson, Sall, Salamon, Allgulander, 2009). It is inversely correlated with self-esteem, infant health status, and years of formal education (Ross, Sawatphanit, Mizuno & Takeo, 2011). High prevalence of depressive symptoms amongst pregnant HIV+ women areassociated with increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes and poor quality of life (Kapetanovic, Dass-Brailsford, Nora & Talisman, 2014). Additionally, women with HIV experience lower levels of emotional support available to them (Bonacquisti, Geller, Aaron, 2014).

Perinatal depression is reported to be as high as 30–50 % in South Africa (Chibanda et al., 2010; Hartley et al., 2011; Rochat, Tomlinson, Barnighausen, Newell, and Stein, 2011; Stewart et al., 2010). InNyanza province of Kenya HIV prevalence is as high as 20.7% in antenatal care settings (Dillabaugh et al., 2012). Stigma is known as a substantial barrier in adhering to and accessing HIV/AIDS care. Furthermore stigma contributes to depressive symptomatology (Rao et al., 2012) compounding the negative impact on women living with HIV.

Methods

Setting and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study with women attending PMTCT clinic at Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH). The clinic serves an average of 160–240 postnatal women every month who are primarily from urban and periurban settlements within Nairobi. Our participants were 18–50 years oldpostnatal women living with HIV recruited at 8-weeks post-delivery. This allowed time for the PCR testing from 6 weeks onwards to ascertain HIV status of their baby. This study was approved by University of Nairobi/Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics and Review Committee (ERC no. P171/03/2014). All postnatal women with severe depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation and alcohol abuse disorder were offered psychosocial support by the researcher and thereafter referred to the Department of Mental health at KNH.

Measurements

We gathered information on participants’ socio-demographics (age, marital status, educational level, occupation, and socio-economic status), clinical information, and psychosocial information. Probes were made on quality of support received from family, significant others on alcohol use and experience with domestic violence. We also assessed presence of STIs, HIV status of the child, and breast/formula feeding practice to understand associated challenges better. On hindsight the response options assessing these associated risks were not as elaborate generating limited information and we do acknowledge this as a limitation of our study. We used the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to screen for and examine severity of depressive symptoms (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987). EPDS is an internationally validated tool for identifying patients at risk for perinatal depression and frequently used in Sub-Saharan Africa (Tsai, Bangsberg, Frongillo, Hunt, Muzoora, Martin, & Weiser, 2013)., Women who scored above 12 were identified as having elevated untreated depressive symptoms. HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument – PLWHA (HASI–P) is a 33-item instrument covering six dimensions of HIV-related stigma: verbal abuse, negative self-perception, and health care neglect, as well as dimensions such as social isolation, fear of contagion, workplace stigma and total perceived stigma (Holzemer et al., 2007). It is built on a four point likert scale with responses ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (mostly). We calculated the median overall stigma and used the median value to categorize the participant to either: 0-never, 1-once or twice, 2-severally, 3-mostly. We found that those with median of 1, 2, and 3 were few and combined them to have a new variable: no stigma and presence of stigma. We found very few responses ranging from once to most options thus we decided to turn stigma from a continuous score into a binary one..

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed data using the SPSS version 20. We employed descriptive univariate analysis to describe the socio-demographics, psychosocial risk factors and depression prevalence. To test relationships amongst these variables, we performed bivariate analyses using chi-square/Fisher’s exact and Kendall’s tau-b tests. Finally multivariate regression model was fitted with depression as an outcome and predictors such as education, family support and levels of HIV/AIDS stigma that were associated in the bivariate analysis with a p value of 0.05. All relationships were described with their odds ratio (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals..

Results

Prevalence of Postpartum depression

The mean age of women in our study was 31years (N=123, SD= 5.2). The EPDS mean score was 11.53 (SD= 5.7) and fifty nine (48%) of our participants met screening criteria for elevated depressive symptoms. We did find it a matter of concern that 29% (n=36) of our participants had suicidal ideation (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of PPD and Associated features

| PPD and associated features | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total EPDS score | Mean 11.53, SD 5.7 | ||

| EPDS score (Ranges 0–30 for Non-Elevated depressive symptoms and Elevated depressive symptoms) | Non-Elevated depressive symptoms | 64 | 52 |

| Elevated depressive symptoms | 59 | 48 | |

| EPDS suicidal ideation intensity | None | 87 | 70.7 |

| Mild | 7 | 5.7 | |

| Moderate | 23 | 18.7 | |

| Severe | 6 | 4.9 | |

| Suicidal ideation | Absent | 87 | 70.7 |

| Present | 36 | 29.3 | |

| Months since birth of child | 0–3 months | 22 | 17.9 |

| 4–6 months | 32 | 26.0 | |

| 7–9 months | 27 | 22.0 | |

| 10–12 months | 21 | 17.1 | |

| 13–15 months | 8 | 6.5 | |

| 16–18 months | 8 | 6.5 | |

| 19–21 months | 4 | 3.3 | |

| 22–24 months | 1 | 0.8 |

Predictors of PPD among women living with HIV

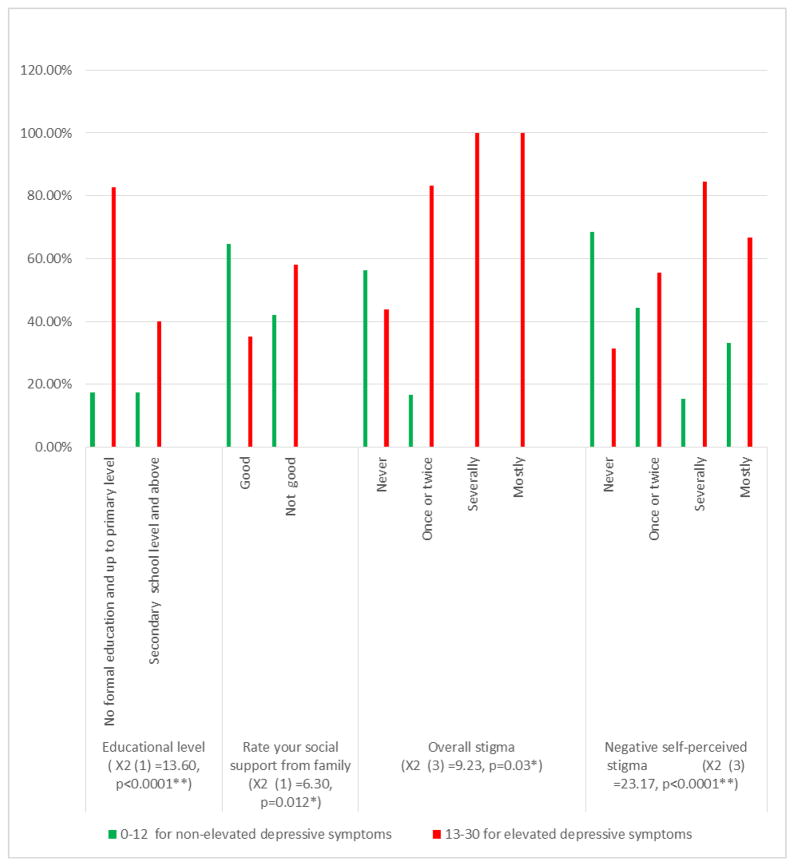

On multivariate analyses (see Figure 1), EPDS score >12 was strongly associated with level of education (χ2(1) =13.60, p<0.0001). Elevated depressive symptoms were also associated with lack of family support (χ2 (1) =6.30, p=0.012). Elevated depressive symptoms were also associated with overall stigma (χ2 (3) =9.23, p=0.03) and particularly with negative self-perceived stigma type (χ2 (3) =23.17, p<0.0001) where poor self-efficacy is co-terminus with the experience of stigma.

Figure 1.

Predictors of PPD among women living with HIV

*Association is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed) **Association is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Eleven (9%) of the participants reported high levels of stigma. Multivariate analyses showed that lower education (OR=0.14, 95% CI [0.04 – 0.46], p=0.001) and lack of family support (OR=2.49, 95% CI [1.14 – 5.42], p=0.02) were associated with presence of elevated depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the presence of stigma implied more than 9 fold risk of development of PPD (OR=9.44, 95% CI [1.132–78.79], p=0.04).

Discussion

We found a large proportion of postpartum women living with HIV experience elevated depressive symptoms. Family social support, educational level, and stigma are common set of risk factors aggravating distress in PPD (Fisher, Mello, Patel, Rahman, Tran, Holton & Holme, 2012; Rao et al., 2012).

PPD was shown to be as high as 30–50 % in multiple studies in Africa (Hartley et al., 2011; Chibanda et al., 2010; Rochat et al., 2011; Stewart et al., 2010). High prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation reported by women in our study is consistent with studies conducted in the region (Gavin, Tabb, Melville, Guo, & Katon, 2011). Our findings can be situated along the following themes.

Depression as a significant challenge in HIV positive women in perinatal spectrum: Fewer studies have been conducted on PPD among women living with HIV. A Ugandan study found 39% of their 447 HIV positive participants from ages 18–49 years screened positive for probable depression (Kaida et al., 2012). Higher levels of HIV-related stigma were significantly associated with elevated depressive symptoms (Endeshaw, Walson, Rawlins, Dessie, Alemu, Andrews, & Rao, 2014). Thus intervening at the PMTCT level itself might reduce psychiatric morbidity and improve adherence and engagement in the program (Abrams, Myer, Rosenfield, & El-Sadr, 2007).

Addressing disempowerment and the absence of support at familial and social levels: Our study participants experienced elevated depressive symptoms and a veritable lack of social support. Social support is known as a strong protective factor against PPD (Robertson, Grace, Wallington. & Stewart, 2004) and support from family members acts as a buffer against depression in women in LMIC settings (Broadhead, Abas, Khumalo, Sakutukwa, Chigwanda, & Garura, 2001). Education was positively associated with PPD in that women who report low rates of depressive symptoms comparatively have higher education (Rao et al., 2012; Prachakul, Grant & Keltner, 2007; Bennetts et al., 1999).

Stigma as a strong determinant of depression in women with HIV: Our results reconfirm that stigma has a strong association with PPD especially in Kenyan cultural context (Dlamini et al., 2007). Both experienced stigma and internalized stigma were strong predictors of PPD among HIV positive South African women (Peltzer & Shikwane, 2011). Other studies in the region too have found that women who had primary education or less have greater adjusted odds of substantial stigma (Cuca et al., 2012).

Study Limitations

EPDS is a screening instrument and not a clinical tool as such limiting our scope. As a pilot project we did not use elaborate psychometric tools to assess risk factors such as social support, alcohol consumption and intimate partner violence in greatrigor.

Caveats and Conclusion

PPD, if left untreated, has adverse effects on mothers and their infants. For the mother, the episode can be the precursor of chronic recurrent depression and for her children PPD can impede their social, emotional, cognitive and physical development (Logsdon, Wisner & Pinto-Foltz, 2006). A concern we noted in our study was select participants’ alcohol abuse despite being on ARVs. Substance use is one of the known barriers to HIV treatment adherence apart from medication side effects and depression (Berg, Michelson, & Safren, 2007) and is also a correlate of PPD (Rubin et al., 2011). Our findings point to the high prevalence of PPD in HIV context. We think that PMTCT might be an ideal context to reach out to women to address mental health problems especially depression screening and offering psychosocial treatments benefitting the mother-baby dyad.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics of the sample (N=123)

| Characteristic | Category | N (N %) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M 31.2, SD 5.2, Median 32 Range 19–48 years |

NS | |

| Number of children | M 2, SD 1, Median 2 | ||

| Religion | Christian | 121(98.4) | NS |

| Muslim | 2(1.6) | ||

| Others | 0(0.0) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 29(23.6) | NS |

| Married | 84(68.3) | ||

| Divorced | 2(1.6) | ||

| Separated | 7(5.7) | ||

| Co-habiting | 1(0.8) | ||

| Educational level | No formal education | 1(0.8) | <0.0001** |

| Primary | 22(17.9) | ||

| Secondary | 38(30.9) | ||

| Diploma courses/Midlevel colleges | 56(45.5) | ||

| UG/PG University | 6(4.9) | ||

| Occupation | Unemployed | 41(33.3) | NS |

| Employed | 26(21.1) | ||

| Self employed | 56(45.5) | ||

| Income in KES | Up to 10,000 | 68(55.3) | NS |

| 10,000–20,000 | 25(20.3) | ||

| 20,000–30,000 | 8(6.5) | ||

| 30,000–40,000 | 10(8.1) | ||

| 40,000–50,000 | 3(2.4) | ||

| above 50,000 | 9(7.3) | ||

| HIV and PMTCT related factors | NS | ||

| When were you diagnosed as HIV positive | Before pregnancy | 64(52.0) | |

| Antenatal clinic | 50(40.7) | ||

| During delivery | 5(4.1) | ||

| After delivery | 4(3.3) | ||

| Where did you deliver the child | Hospital | 123(100.0) | NS |

| Home | 0(0.0) | ||

| Did your child cry immediately after delivery | Yes | 113(91.9) | 0.034* |

| No | 10(8.1) | ||

| Do you know HIV status of child | Positive | 4(3.3) | NS |

| Negative | 107(87.0) | ||

| not sure | 12(9.8) | ||

| Does your child experience frequent sickness | Yes | 14(11.4) | NS |

| No | 109(88.6) | ||

| How do you feed your child at the moment | Exclusive breastfeeding | 64(52.0) | NS |

| Formula feeding | 10(8.1) | ||

| Mixed feeding | 49(39.8) | ||

| Have you been treated from STI in the past one month | Yes | 12(9.8) | NS |

| No | 111(90.2) | ||

| Rate your social support from family | Good | 54(43.9) | 0.012* |

| Not good | 69(56.1) | ||

| Rate your social support from friends | Good | 37(30.1) | NS |

| Not good | 86(69.9) | ||

| Rate your social support from significant others | Good | 19(15.4) | NS |

| Not good | 104(84.6) | ||

| Did you drink alcohol (beer, wine, home-brewed beer or spirits) in the past one month | Yes | 20(16.3) | NS |

| No | 103(83.7) | ||

| Has your male partner abused you since the delivery of this child? | Physically | 9(8.4) | NS |

| Emotionally | 21(19.6) | ||

| None (supportive) | 77(72.0) | ||

| Does your male partner engage in extramarital sexual affairs? | Yes | 25(23.6) | NS |

| No | 78(73.6) | ||

| Not sure | 3(2.8) | ||

chi-square and kendell’s tau b significant at the 0.05 level

significant at the 0.01 level

Acknowledgments

Thanks to staff at KNH-PMTCT clinic staff and participants. We also thank Francis Njiri, University of Nairobi for his data analytic support. This project was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health grant R25-MH099132.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Obadia Yator, Email: obadiayator@gmail.com.

Dr. Muthoni Muthoni, Email: mathai@web.de.

Ann Van der Stoep, Email: annv@uw.edu.

Deepa Rao, Email: deeparao@uw.edu.

Manasi Kumar, Email: manni_3in@hotmail.com.

References

- Abrams EJ, Myer L, Rosenfield A, El-Sadr WM. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission services as a gateway to family-based human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment in resource-limited settings: rationale and international experiences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:S101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.068. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetts A, Shaffer N, Manopaiboon C, Chaiyakul P, Siriwasin W, Mock P, … Clark L. Determinants of depression and HIV related worry among HIV-positive women who have recently given birth, Bangkok, Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(6):737–749. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Michelson SE, Safren SA. Behavioral aspects of HIV care: Adherence, depression, substance use, and HIV transmission Behaviors. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:181–200. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacquisti A, Geller PA, Aaron E. Rates and predictors of prenatal depression in women living with and without HIV. AIDS Care. 2014;26(1):100–6. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.802277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead J, Abas M, Khumalo Sakutukwa G, Chigwanda M, Garura E. Social support and life events as risk factors for depression amongst women in an urban setting in Zimbabwe. Soc Psychiatr Epidemio. 2001;36:115–22. doi: 10.1007/s001270050299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Mangezi W, Tshimanga M, Woelk G, Rusakaniko P, Stranix-Chibanda L, … Shetty AK. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale among women in a high HIV prevalence area in urban Zimbabwe. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13:201–6. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. B J Psych. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuca Y, Onono M, Bukusi E, Turan J. Factors Associated with Pregnant Women’s Anticipations and Experiences of HIV-related Stigma in Rural Kenya. AIDS Care. 2012;24(9):1173–1180. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.699669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35:73–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillabaugh LL, Lewis-Kulzer J, Owuor K, Ndege V, Oyanga A, Ngugi E, … Makoae LN. Verbal and physical abuse and neglect as manifestations of HIV/AIDS stigma in five African countries. Public Health Nursing. 2007;24(5):389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endeshaw M, Walson J, Rawlins S, Dessie A, Alemu S, Andrews N, Rao D. Stigma in Ethiopia: Association with depressive symptoms in people with HIV. AIDS Care. 2014;26:8, 935–939. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.869537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Mello MC, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, Holmes W. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90(2):139–149. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.091850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin AR, Tabb KM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Katon W. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2011;14(3):239–246. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0207-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley C, Pretorius K, Mohamed A, Laughton B, Madhi S, Cotton MF, … Seedat S. Maternal postpartum depression and infant social withdrawal among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive mother-infant dyads. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15(3):278–287. doi: 10.1080/13548501003615258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, Comulada W, Stewart J, le Roux I, Mbewu N, Rotheram-Borus M. Depressed mood in pregnancy: prevalence and correlates in two Cape Town peri-urban settlements. Reprod Health. 2011;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL, Uys LR, Chirwa ML, Greeff M, Makoae LN, Kohi TW, … Durrheim K. Validation of the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument - PLWA(HASI-P) AIDS Care. 2007;19(8):1002–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540120701245999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida A, Matthews L, Ashaba S, Tsai A, Kanters S, Robak M, … Bangsberg D. Depression During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Among HIV-Infected Women on Antiretroviral Therapy in Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;67(4):S179–187. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S, Dass-Brailsford P, Nora D, Talisman N. Mental health of HIV-seropositive women during pregnancy and postpartum period: a comprehensive literature review. AIDS & Behavior. 2014;18:1152–1173. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0728-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten-Alvarez LE, Hosman CM, Riksen-Walraven JM, Van doesum KT, Smeekens S, Hoefnagels C. Early school outcomes for children of postpartum depressed mothers: comparison with a community sample. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43(2):201. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0257-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotze M, Visser M, Makin J, Sikkema K, Forsyth B. The coping strategies used over a two-year period by HIV-positive women who had been diagnosed during pregnancy. AIDS Care. 2013;25(6):695–701.18. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0257-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon MC, Wisner KL, Pinto-Foltz MD. The impact of postpartum depression on mothering. Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing. 2006;35(5):652–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owe-Larsson B, Sall L, Salamon E, Allgulander C. HIV infection and psychiatric illness. Afr J Psychiatry. 2009;12(2):115–28. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v12i2.43729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Shikwane ME. Prevalence of postnatal depression and associated factors among HIV-positive women in primary care in Nkangala district, South Africa. South Afr J HIV Med. 2011;12(4):24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Prachakul W, Grant JS, Keltner NL. Relationships among functional social Support, HIV-related stigma, social problem solving, and depressive symptoms in people living with HIV: A Pilot Study. AIDS Care. 2007;18(6):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.08.002. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Chen WT, Pearson CR, Simoni J, Fredriksen-Goldsen K, Nelson K, … Zhang F. Social support mediates the relationship between HIV stigma and depression/quality of life among people living with HIV in Beijing, China. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(7):481–4. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart R. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Barnighausen T, Newell ML, Stein A. The prevalence and clinical presentation of antenatal depression in rural South Africa. J Affect Disorders. 2011;135(1):362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R, Sawatphanit W, Mizuno M, Keiko T. Depressive symptoms among HIV-positive postpartum women in Thailand. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2011;25(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin Cook J, Grey D, Weber K, Wells C, Golub E, … Maki P. Perinatal depressive symptoms in HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected women: An AIDS Behav 123 prospective study from preconception to postpartum. J Womens Health. 2011;20(9):1287–95. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R, Bunn J, Vokhiwa M, Umar E, Kauye F, Fitzgerald M, … Creed F. Common mental disorder and associated factors amongst women with young infants in rural Malawi. Soc Psych Epid. 2010;45(5):551–559. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, Hunt PW, Muzoora C, Martin JN, Weiser SD. Reliability and validity of instruments for assessing perinatal depression in African settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2008;65(7):805–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]