Abstract

End-user involvement in HIV guidelines development is often little, late or absent. Other disciplines have long advocated ‘handing over the stick’ (i.e. power and control), as both ethical and strategic. Women HIV activists have called this respectful engagement with, and learning from, communities ‘MIWA’ (meaningful involvement of women living with HIV and AIDS).

Keywords: meaningful involvement of women living with HIV and AIDS (MIWA), participation, participatory research, women's rights, HIV, sexual and reproductive health, global consultation, World Health Organization (WHO), ethics

End-user involvement in HIV guidelines development is often little, late or absent. Other disciplines have long advocated ‘handing over the stick’ (i.e. power and control), as both ethical and strategic. Women HIV activists have called this respectful engagement with, and learning from, communities ‘MIWA’ (meaningful involvement of women living with HIV and AIDS). Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned a global values and preferences consultation, led by user-investigators [1] prior to starting a sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and human rights of women living with HIV guidelines update [2].

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 27, articulates the ethics of engaging individuals in advancement of science [3]. MIWA [4] has three other key antecedents: Hart's 1989 UNICEF ‘ladder of participation’ for children [5]; the 1983 ‘GIPA Principles’ (Greater Involvement of People with HIV and AIDS) [6]; and the 1970s feminist manual ‘Our Bodies Ourselves’ [7,8]. Community-based participatory principles, promoted by these and other academics were followed [9–12]. Feeling involved in an effective response to a traumatic experience is an important coping strategy [13]. Thus policy-makers’ engagement with women living with HIV throughout guidelines’ development alone is a positive strategic outcome. Furthermore, research processes grounded in lived experiences form a firmer base for global policy guidelines [14,15].

Three MIWA principles are participation, diversity and ethics. Thus, the competitively appointed core research team, led by Salamander Trust, with ATHENA Network, formed a Global Reference Group (GRG) of 14 women living with HIV as its key advisory group throughout. Reflecting a diversity of geography, ages, identities and HIV-acquisition routes, they connected with other women with HIV in all their diversities as respondents.

GRG pre-survey discussions elicited that women with HIV have felt bombarded by intrusive surveys, conducted by salaried researchers who expect time-consuming unpaid responses. Questions often feel negative or irrelevant. Results are rarely shared. Respondents thus feel further disempowered, producing survey fatigue. Instead, the user-investigators adopted an ‘appreciative inquiry’ approach [16], rooted ethically in positive informed language [17], replacing problems with visions. This offers opportunities for pro-active engagement in a creative, future-oriented process, thereby reducing past trauma [16].

To ascertain priority themes, GRG members conducted small pre-consultation exercises with their peers. Next, all members helped draft and pilot a survey before promoting it widely. The anonymous, confidential online survey explained its purposes, structure and definitions and ran for 6 weeks in seven languages. Before they could proceed, respondents confirmed that they were women living with HIV and that their anonymised responses could be published. Focus-group discussion (FGD) participants (for women without internet) gave similar prior written or verbal consent. Participants could choose not to answer any question or discontinue at any time.

The core team and 13 GRG members subsequently met around 30 UN staff and Guidelines Development Group members in Geneva to present and discuss the survey findings [1,18–21], and share personal experiences of the issues.

To ascertain whether the MIWA principles of participation, diversity and ethics outlined above were successfully achieved, narrative process observations were examined from survey respondents and meeting participants. Many answers indicated that respondents felt involved in the process, a positive outcome in itself. There was evidence that respondents felt confidence in the authenticity of questions, some using the survey to explore experiences never previously shared.

Even though there were questions about violence and trauma that could have felt difficult, the fact that the survey was written by and for women living with HIV in a tone that is empowering rather than victimising, made my participation feel good.

(Respondent, USA)

This was the largest, most diverse global survey to date of women living with HIV, with 945 responses from 94 countries (832 women responded in seven languages online and 113 women responded through 11 FGDs). Through GRG members, women with many backgrounds engaged, including women who: use drugs; do or who have done sex work; are lesbians, bisexual or transgender; have experienced rape or other sexual violence or conflict; are migrants, homeless or have been incarcerated; are indigenous women; are young; are mothers or have no children – and women with HIV who identified with several or none of these experiences. Some described the survey as an important, informative community advocacy tool, presenting a comprehensive picture of how SRH and human rights reciprocally affect all life's facets – physical, psychosocial, material, sexual and spiritual. The GRG learned about guideline development, describing the experience as empowering, engaging and a refreshing affirmation of MIWA. Other meeting participants also found the process informative and valuable.

It's been a privilege. Humanising the issue as a methodology.

(WHO staff member)

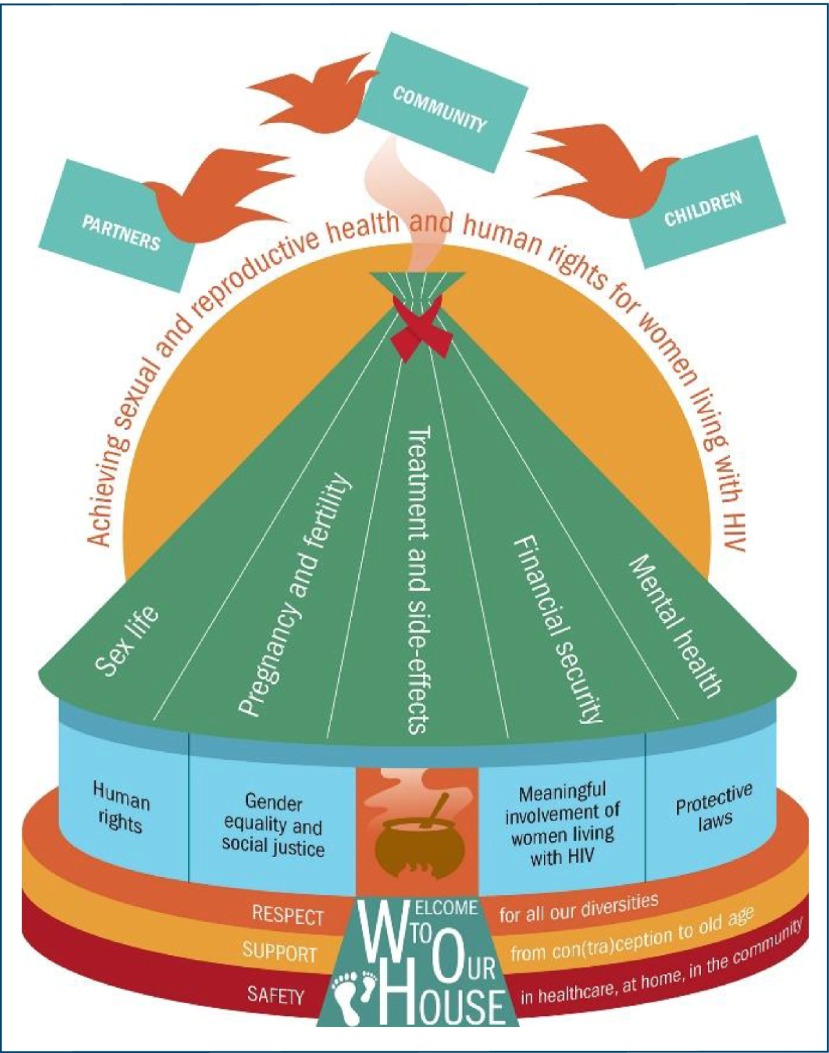

To structure and share research results widely, for and with respondents and policy-makers, the survey report employed the commonly recognisable metaphor of a house (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Image used in the survey report to reflect the inter-connectedness of findings

This snowball sample survey cannot claim representation of 15 million women with HIV globally and there were inevitable limitations: although promoted widely, time-limited online surveys exclude many, with gender a key factor [22]. Respondents need to feel hopeful enough to engage and unknown numbers chose not to respond. Most respondents were aged 30–50 and women in detention and conflict areas were absent. The $70,000 budget, whilst helpful, enabled only 11 FGDs; most translations and article writing were voluntary.

None the less, the biggest global survey yet was a welcomed first for WHO [1]. The breadth and depth of engagement, with comprehensive research results and detailed positive feedback, suggest MIWA was achieved. This user-led consultation sets new standards for a principled process of meaningful involvement from the outset, which may even be cost-saving. We speculate that by appointing a GRG with diverse membership, seeking their close engagement in the study development, and upholding ethical format and content principles, the study engaged diverse respondents through speaking to their lived experiences and enabling them to feel respected as change agents.

It is hoped that the guideline will fulfil most of the respondents’ desires.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Dr Manjulaa Narasimhan of WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Rights, who commissioned the consultation on which this article is based. Many thanks also to all the Global Reference Group members and to all the respondents who contributed so richly to the consultation findings.

Conflict of interests

Angelina Namiba, Marijo Vazquez and Alice Welbourn are women living with HIV. We declare no other conflicting interests.

Funding

The consultation on which this article is based was commissioned and funded by WHO.

Disclaimer

The content of the paper is the responsibility of the authors alone. WHO may not necessarily agree.

References

- 1. Orza L, Welbourn A, Bewley S, Crone E, Vazquez M. Building a safe house on firm ground: key findings from a global values and preferences survey regarding the sexual and reproductive health and human rights of women living with HIV [Internet]. Salamander Trust; 2015. Available from: http://salamandertrust.net/resources/BuildingASafeHouseOnFirmGroundFINALreport190115.pdf ( accessed February 2016).

- 2. World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund Sexual and reproductive health of women living with HIV/AIDS: Guidelines on care, treatment and support for women living with HIV and their children in resource-constrained settings. 2006. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/924159425X_eng.pdf ( accessed Febraury 2016).

- 3. United Nations The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948.

- 4. MIWA Participation Tree: Is your organisation bearing fruit? ICW, 2004. Available at: http://wecareplus.net/resources/Policybriefing_ENGJuly2011.pdf

- 5. Hart R. Children's Participation: From tokenism to citizenship. UNICEF, 1992. Available at: http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/childrens_participation.pdf ( accessed February 2016).

- 6. The Denver Principles The People with AIDS Advisory Committee; 1983. Available at: www.actupny.org/documents/Denver.html ( accessed February 2016).

- 7. Boston Women's Health Collective Our Bodies Ourselves: A Book by and for Women. 2nd edn Touchstone, New York; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strub S. Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics, Sex, AIDS and Survival. Scribner, New York; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cornwall A, Welbourn A. Realizing Rights: Participatory Approaches to Sexual and Reproductive Well-Being. Zed Books, London; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guijt I, Shah M. The Myth of Community. Intermediate Technology Publications, London; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization Putting Women First: Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence Against Women. 2001. Available at: http://www.who.int/gender/violence/womenfirtseng.pdf ( accessed February 2016).

- 12. International Community of Women living with HIV/AIDS Guidelines on ethical participatory research with HIV positive women. 2004. Available at: www.icw.org/files/EthicalGuidelinesICW-07-04.pdf ( accessed February 2016).

- 13. Minogue V, Boness J, Brown A, Girdlestone J. The impact of service user involvement in research. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 2005; 18: 103– 112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization Handbook for Guideline Development. 2nd edn 2014. Available at: www.who.int/kms/handbook_2nd_ed.pdf ( accessed February 2016).

- 15. Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co.; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reid K, Flowers P, Larking M. Exploring lived experience. The Psychologist 2005; 18: 20– 23. [Google Scholar]

- 17. McAdam E, Mirza K. Drugs, hopes and dreams: appreciative inquiry with marginalized young people using drugs and alcohol. J Family Therapy 2009; 31: 175– 193. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dilmitis S, Edwards O, Hull B et al. Language, identity and HIV: why do we keep talking about the responsible and responsive use of language? Language matters. J Int AIDS Soc 2012; 15 ( Suppl 2): 17990. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Narasimhan M, Orza L, Welbourn A et al. Ensuring users values and preferences in WHO guidelines: Sexual and reproductive health and human rights of women living with HIV. ( Accepted for publication by WHO Bulletin)

- 20. Orza L, Bewley S, Chung C et al. ‘ Violence. Enough already’: findings from a global participatory survey among women living with HIV. J Int AIDS Soc 2015; 18( Suppl 5): 20285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Orza L, Bewley S, Logie C et al. How does living with HIV impact on women's mental health? Voices from a global survey. J Int AIDS Soc 2015; 18( Suppl 5): 20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cooper J. The digital divide: the special case of gender. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 2006; 22: 320– 334. [Google Scholar]