Abstract

We examined the role of intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity on 18F-FDG PET during concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) in predicting survival outcomes for patients with cervical cancer. This prospective study consisted of 44 patients with bulky (≥ 4 cm) cervical cancer treated with CCRT. All patients underwent serial 18F-FDG PET studies. Primary cervical tumor standardized uptake values, metabolic tumor volume, and total lesion glycolysis (TLG) were measured in pretreatment and intra-treatment (2 weeks) PET scans. Regional textural features were analyzed using the grey level run length encoding method (GLRLM) and grey-level size zone matrix. Associations between PET parameters and overall survival (OS) were tested by Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression model. In univariate analysis, pretreatment grey-level nonuniformity (GLNU) > 48 by GLRLM textural analysis and intra-treatment decline of run length nonuniformity < 55% and the decline of TLG (∆TLG) < 60% were associated with significantly worse OS. In multivariate analysis, only ∆TLG was significant (P = 0.009). Combining pretreatment with intra-treatment factors, we defined the patients with a initial GLNU > 48 and a ∆TLG ≤ 60% as the high-risk group and the other patients as the low-risk. The 5-year OS rate for the high-risk group was significantly worse than that for the low-risk group (42% vs. 81%, respectively, P = 0.001). The heterogeneity of intratumoral FDG distribution and the early temporal change in TLG may be an important predictor for OS in patients with bulky cervical cancer. This gives the opportunity to adjust individualized regimens early in the treatment course.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, chemoradiotherapy, 18F-FDG PET, texture analysis

Introduction

In spite of the improvement in survival of cervical cancer after concurrent chemoradiotherapy, the outcomes of patients with locally advanced cervical cancer have been unsatisfactory [1]. Several pretreatment clinical characteristics are used to predict the risk of recurrence [2]. Kang et al. have suggested a combination of nonsquamous cell histology, serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen levels, and nodal positivity along with [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) to estimate the risk of distant metastasis [3]. High FDG uptake in the primary cervical tumor, measured as the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), has been reported to predict for lymph node involvement, treatment response, and overall survival [4]. However, other studies showed that SUVmax was not significantly correlated with post-treatment response [5,6]. There is emerging evidence that intratumoral heterogeneity of FDG uptake could be a better predictor for treatment outcomes. Textural features of tumor metabolic distribution extracted from pretreatment 18F-FDG PET images have been reported to predict response to chemoradiotherapy and survival outcomes in sarcoma, esophageal cancer, head and neck cancer, and lung cancer [7-11]. Similarly, it has been shown in cervical cancer that intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity on pretreatment 18F-FDG PET can predict response to therapy and risk of pelvic recurrence [12,13].

In addition to using pretreatment PET data, several studies suggest that early changes of 18F-FDG PET uptake after initial treatment is an independent outcome predictor [6]. It was reported that changes in textural feature were independently associated with overall survival (OS) and response to target therapy in rectal cancer and non-small cell lung cancer [14,15]. Only one study explored the temporal changes of intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity measured by textural analysis during the course of concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) in cervical cancer. Yang et al. showed that textural features on a regional scale with emphasis on characterizing contiguous regions of high uptake in tumors decreased significantly with time in the complete metabolic response group [16]. However, this study included only 20 patients with stage IB1 to IVA cervical cancer and the end point was the tumor response rather than survival outcome, which is more clinical relevant.

In this study, we aim to investigate the prognostic value of feature parameters extracted from serial 18F-FDG PET scans acquired before treatment, after 2 and 4 weeks of treatments, complete treatment, and 2 months after completion of treatment. Intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity with regional scale texture features was analyzed to predict the OS of patients with bulky cervical cancer.

Materials and methods

Patients

The enrolled patients had clinical FIGO stage IB2 to IVa cervical cancers with tumor diameters larger than 4 cm defined by T2-weighted MRI. Patients who were contraindicated to MRI examinations, such as those with pacemakers, metal objects, or claustrophobia disorder were excluded. The other inclusion criteria in this prospective study were the following: normal renal, hepatic and hematologic function, and no previous chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or surgery for cancer. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital (#98-0740A3) and abided with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration on good clinical practice. All patients signed informed consent.

18F-FDG PET acquisition

All patients underwent FDG PET/CT with standardized procedures. Participants fasted for at least 6 hours prior to examination. Images were obtained 50 min after intravenous injection of 370-555 MBq 18F-FDG [17]. PET/CT scans were acquired using the same protocol as previous report [9]. Baseline pre-CCRT whole-body PET was performed within 2 weeks before the start of treatment. Locoregional PET was performed during CCRT at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks and post-CCRT whole-body PET 2 month after the completion of treatment.

18F-FDG PET image analysis

18F-FDG PET lymph node status were interpreted visually and semiquantitatively according to our previous protocol [18]. Evaluation of metabolic response is accomplished by comparing the relative changes in tumor FDG uptake. On the basis of the Positron Emission Tomography Response Criteria in Solid Tumors (PERCIST) guidelines, patients were classified as complete metabolic responders (CMR; complete resolution of tumor FDG uptake), partial metabolic responders (PMR; reduction of a minimum of 30% in target measurable lesion), stable metabolic disease (SMD; not CMR, PMR, or progressive metabolic disease (PMD)), or progressive metabolic disease (PMD; increase of a minimum of 30% in target measurable lesion or presentation of a new lesion) [19].

Tumors were segmented using the PMOD 3.3 software package (PMOD Technologies Ltd, Zurich, Switzerland). The boundaries were drawn to include the primary cervical tumor on the axial 18F-FDG PET images. The lesions were automatically contoured at a threshold 40% of maximum SUV [20], and the voxels within the contouring margin were incorporated to define the metabolic tumor volume (MTV). The total lesion glycolysis (TLG) was calculated according to the following formula: TLG = mean SUV × MTV (cm3) [21].

For texture analysis, we used the same parameters as the Yang’s study to verify the prognostic value of these textural features for survival outcomes [16]. The grey-level run length encoding matrix (GLRLM) and grey-level size zone matrix (GLSZM) were used for assessing the regional textural features [22,23]. A total of 22 different textural features were extracted from the GLRLM and GLSZM (Supplementary Table 1). Besides, changes in these parameters over the course of therapy were also investigated. The textural features were analyzed using a software package (Chang-Gung Image Texture Analysis toolbox, CGITA) implemented under MATLAB 2012a (Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA) [10,24].

Treatment

The pretreatment workup, including pelvic and abdominal MRI and 18F-FDG PET, and radiation treatment, was similar to our previous report [25]. In brief, patients were treated with external-beam radiotherapy (RT) initially delivered with a daily fraction 1.8 Gy in five fractions weekly. Large-field radiation doses to the whole pelvis were 45 Gy via a four-field box technique. When the involvement of common iliac or para-aortic lymph nodes was suspected from imaging studies, irradiation fields were extended to the abdominal para-aortic region. For patients with lower vaginal tumor extension, bladder or rectal invasion, or persistent bulky tumor after 45 Gy RT, who were not undergoing brachytherapy, the primary tumor was treated with total doses of 68-72 Gy. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) was allowed for patients treated with para-aortic irradiation or without brachytherapy. Patients undergoing brachytherapy with six fractions of 4.3 Gy to point A received a parametrial boost dose (5.4-12.6 Gy) by parallel-opposed anterior-posterior fields with a 4-cm-wide midline block. The gross nodal lesions outside the parametrial boost field were treated to a total dose up of 54-57.6 Gy. The chemotherapy protocol included six cycles of weekly intravenous infusions with cisplatin 40 mg/m2 during the radiotherapy course.

Statistical analysis

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to evaluate the accuracy of the PET texture features in predicting post-CCRT response according to PERCIST. The parameters with an area under the curve (AUC) greater than 0.75 as good performance were selected for further analyses [26]. The optimal cutoff values were identified by determining the values where the sum of sensitivity and specificity was maximal. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were constructed and compared using the log-rank test. Cox-regression model with the forward stepwise method was used for multivariate analysis. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to express the results of multivariate analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc.). Two-tailed P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between November 2007 and July 2010, a total of consecutive 48 patients were eligible for this study. Four patients were excluded: one died of GI bleeding during treatment, one had synchronic ovarian cancer, and the other two had corrupted data that could not be analyzed. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 44 participants.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 44)

| Characteristic | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| Median, range | 51.7, 23 to 81 |

| FIGO stage | |

| IB1 | 1 (2) |

| IB2 | 8 (18) |

| IIA | 3 (7) |

| IIB | 17 (39) |

| IIIA | 1 (2) |

| IIIB | 14 (32) |

| Pathology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 5 (11) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 39 (89) |

| Level of SCC Ag (ng/mL) | |

| Median, range | 13, 0-165 |

| 18F-FDG PET lymph node status | |

| None | 21 (48) |

| Pelvic | 22 (50) |

| Para-aortic | 6 (14) |

Metabolic response

Locoregional PET during CCRT at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks were performed. PET at 2 weeks revealed that 5 (11%) patients had CMR, 24 (55%) had PMR, and 15 (34%) had SMD. PET at 4 weeks showed 23 (52%) CMR, 18 (41%) PMR, and 3 (7%) SMD. PET at 8 weeks revealed 27 (61%) CMR, 10 (23%) PMR, and 7 (16%) SMD. Post-CCRT whole-body PET demonstrated 27 (61%) had CMR, 10 (23%) had PMR, 3 (7%) SMD, and 4 (9%) PMD. Among the 4 patients with PMD, new lesions were found in two patients with supraclavicular lymph node metastasis, one with lung metastases, and the other with pelvic bone metastasis. Because more than half of patients had no measurable tumor at 4 weeks and 8 weeks, only the results of PET at 2 weeks were used for texture analysis.

Response prediction

Imaging parameters including SUVmax, MTV, TLG, and 22 different textural features acquired at pretreatment and their changes during treatment at 2 weeks were analyzed for response prediction. Nine imaging parameters, including four at pretreatment and five at 2 weeks, were good predictors of post-CCRT CMR with AUC greater than 0.75 and P values less than 0.05. The details are listed in Table 2. Patients with CMR (n = 28) had significantly better overall 5-year survival rates than those with non-CMR (n = 16) (82% vs 50%, respectively, P = 0.002).

Table 2.

Significantly good imaging parameters in ROC analysis

| Area under ROC curve | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment 18F-FDG PET | |||

| Short runs emphasis (SRE) | 0.75 | 0.32-0.68 | 0.006 |

| Long runs emphasis (LRE) | 0.75 | 0.60-0.91 | 0.005 |

| Gray-level nonuniformity (GLNU)* | 0.76 | 0.56-0.88 | 0.005 |

| Large zones emphasis (LZE) | 0.76 | 0.60-0.91 | 0.004 |

| 2nd-week 18F-FDG PET | |||

| ∆SUVmax | 0.75 | 0.56-0.89 | 0.006 |

| ∆MTV | 0.77 | 0.66-0.93 | 0.004 |

| ∆TLG | 0.81 | 0.62-0.92 | 0.001 |

| ∆Run length nonuniformity (RLNU) | 0.75 | 0.61-0.91 | 0.006 |

| ∆Gray-level nonuniformity (GLNU)† | 0.77 | 0.61-0.91 | 0.003 |

ROC receiver operating characteristic, SUVmax maximum standardized uptake value, MTV metabolic tumor volume, TLG total lesion glycolysis.

Derived from grey level run length encoding method.

Derived from grey-level size zone matrix.

Survival prediction

The median follow-up time in the study cohort was 56 months (range 10-83 months). By the end of the follow-up period, 14 patients had died. The nine imaging parameters with good prediction power for CMR were analyzed for survival outcomes. Only one pretreatment factor, grey-level nonuniformity (GLNU) > 48, derived from GLRLM textural analysis, was associated with worse OS in univariate analysis (P = 0.031). As shown in Table 3, other clinical factors such as age, FIGO stage, pathology, cell differentiation, and 18F-FDG PET lymph node status were not significantly associated with OS. For intra-treatment factors, the decline of run length nonuniformity (∆RLNU) < 55% and the decline of TLG (∆TLG) < 60% were associated with worse OS in univariate analysis (P = 0.026 and 0.004, respectively). In multivariate analysis, only ∆TLG was a significant variable (P = 0.009).

Table 3.

Prognostic factors and significant textural parameters in univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of overall survival rate

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (as continuous variable) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.231 | ||

| FIGO stage III-IV | 1.53 (0.53-4.43) | 0.431 | ||

| PLN positive by PET | 1.65 (0.57-4.77) | 0.347 | ||

| PALN positive by PET | 1.50 (0.42-5.40) | 0.533 | ||

| ∆SUVmax decline < 30% | 1.78 (0.61-5.15) | 0.280 | ||

| ∆MTV decline < 60% | 2.29 (0.72-7.34) | 0.150 | ||

| ∆TLG decline < 60% | 4.70 (1.47-15.04) | 0.004 | 4.70 (1.47-15.04) | 0.009 |

| GLNU > 48 | 3.13 (1.05-9.38) | 0.031 | ||

| ∆RLNU decline < 55% | 3.68 (1.07-13.91) | 0.026 | ||

PLN pelvic lymph node, PALN para-aortic lymph node, SUVmax maximum standardized uptake value, MTV metabolic tumor volume, TLG total lesion glycolysis, GLNU gray-level nonuniformity, RLNU Run length nonuniformity.

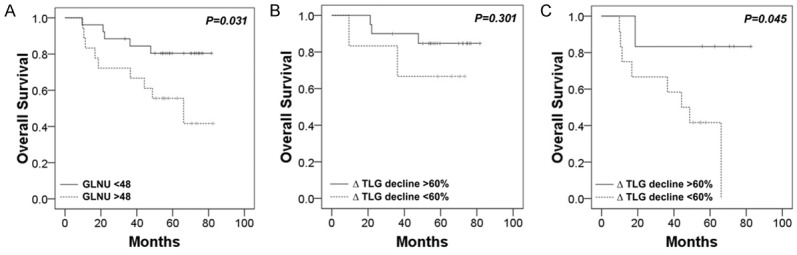

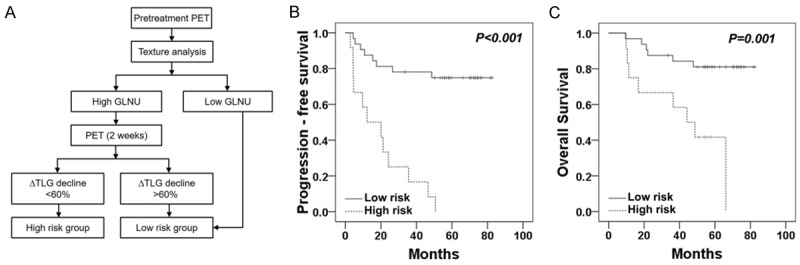

In order to better stratify the risk of disease progression before the end of treatment, we combined the pretreatment factor GLNU with intra-treatment factor ∆TLG for risk assessment. In the low GLNU (≤ 48) group, ∆TLG could not further stratify disease risk. However, in the high GLNU (> 48) group, patients with a lesser ∆TLG decline (≤ 60%) had significantly worse survival outcomes than those with a higher ∆TLG decline (> 60%) (P = 0.045) (Figure 1). Therefore, we defined the patients with a high initial GLNU (> 48) and a lower ∆TLG decline (≤ 60%) as a high risk group (n = 12). The patients with low GLNU (≤ 48) or high GLNU (> 48) with a higher ∆TLG decline (> 60%) as a low risk group (n = 32) (Figure 2A). For high risk group, 83% (10/12) patients became non-CMR after CCRT. The progression free survival rate for the high risk group was significantly worse than that for the low risk group (17% vs. 78% for 3-year and 8% vs. 75% for 5-year, respectively, P < 0.001) (Figure 2B). Similarly, the OS rate for the high risk group was significantly worse than that for the low risk group (67% vs. 88% for 3-year and 42% vs. 81% for 5-year, respectively, P = 0.001) (Figure 2C).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival according to the textural feature gray-level nonuniformity (GLNU) extracted from pretreatment 18F-FDG PET in study cohort (n = 44) (A). Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival according to the change of total lesion glycolysis (ΔTLG) based on 2nd-week 18F-FDG PET in patients with low GLNU (n = 26) (B) and high GLNU (n = 18) (C). In the high GLNU group, patients with poor treatment response (lesser ∆TLG decline) had significantly worse survival outcomes.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of two-step risk-stratification strategy based on pretreatment and intra-treatment PET imaging parameters (A). Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival (B) and overall survival (C) according to the risk group of patients.

Patterns of failure

Of 12 patients defined as the high risk group, 11 (92%) experienced disease recurrence. Two patients had isolated local failure, and 9 patients developed distant metastasis, including 3 patients who had both local and distant failures. For 32 patients defined as the low risk group, 8 patients (25%) had distant failures, including 1 combined local plus distant failure (Table 4). In the high risk group, one patient with supraclavicular lymph node recurrence and one patient with para-aortic lymph node relapse were salvaged. Another patient with cervical and para-aortic lymph node recurrence was salvaged by surgery and CCRT. In the low risk group, one patient with supraclavicular lymph node relapse was salvaged, while one patient with lung metastasis was still alive with disease.

Table 4.

Patterns of failure in low risk group and high risk group patients

| Low risk group (n = 32) | High risk group (n = 12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Local | 2 | |

| Both local and distant | ||

| Local+PALN | 1 | 2 |

| Local+PALN+ScLN | 1 | |

| Distant | ||

| PALN only | 1 | |

| ScLN only | 1 | 1 |

| Solid organs ± LN | 6 | 4 |

| Total | 8 | 11 |

PALN para-aortic lymph node, ScLN supraclavicular lymph node.

Discussion

18F-FDG PET has proved to predict the outcome for cervical cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy [27-32]. However, most of the predictions were based on the post-therapy metabolic response, which is too late to modify the treatment for patients with potentially poor outcome. In this study, a high risk group of patients with bulky cervical cancer was identified by the texture analysis of the pretreatment and week 2 18F-FDG PET examinations. Our findings have significantly practical implications to help tailor the treatment for individual patients, particularly if the tumor is not responding well to a standard CCRT in the early treatment course.

18F-FDG PET is now widely used in oncological imaging for diagnosis and staging, and increasingly to determine early response to treatment by employing semiquantitative measures of lesion activity such as SUV. However, using SUVs from a baseline scan to predict the behavior of a tumor in terms of future therapy response or prognosis is of limited value [5]. Post-therapy 18F-FDG PET could provide valuable long-term prognostic information in cervical cancer [27]. Our results showed that patients with CMR 2 months after CCRT had a 82% 5-year survival rate, compared to 50% for those without CMR. This information may be used to select patients for salvaged therapy, but it is too late to select patients for more aggressive treatment.

The measurement of texture indices from tumor PET images has also been recently proposed as an adjunct to predict tumor response to therapy. Heterogeneity of FDG uptake within tumor could be associated with more aggressive behavior and poorer response to treatment [8,11,14]. Although some suggested that FDG heterogeneity by taking the derivative of the volume-threshold function were not predictive of disease outcome [33], we adopted the methods reported by Yang et al. using regional textural features calculated from GLRLM and GLSZM analysis [16]. These parameters represent runs and zones with different gray-level values to describe contiguous regions of constant intensity in a tumor.

In this study, we found that intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity depicted by regional textural features could predict tumor response to CCRT and survival outcomes in patients with bulky cervical cancer. GLNU provides further information for survival prognosis in addition to clinical characteristics, such as tumor volume and nodal status. This result is similar to Aerts et al. who showed that GLNU by CT scan is the top performing feature for the survival of patients with lung cancer and head and neck cancer [34]. It is interesting to show the translational capability of radiomics in different cancer types and image modalities.

Treatment response during the course of therapy can enable risk-adapted management. Clinical examinations [35] and tumor markers in the blood [36] have been used previously to evaluate treatment response of cervical cancer. Serial PET imaging has the advantage of being able to measure therapy response early in the course of treatment in a number of cancers [37,38] but the appropriate time to acquired PET information during treatment is still undetermined. In cervical cancer, Yang et al. demonstrated that neither the SUV indices nor the textural features investigated before the treatment initiation was able to predict treatment response, but suggested that changes in tumor heterogeneity during therapy may serve as a better predictor of response than a single measurement prior to treatment [16]. In our study, more than half of the primary tumors became unmeasurable at 4 weeks. In addition, many of the regressed tumors at 4 weeks became too small to be assessed because of the requirement being for a reasonable number of adjacent pixels to be present to be able to measure some of the texture features [39]. In this study, several imaging parameters at pretreatment and some at 2 weeks were identified as good predictors of post-CCRT CMR. Interestingly, both pretreatment GLNU derived from GLRLM analysis and ∆GLNU at 2 weeks derived from GLSZM analysis were predictors of tumor response while only pretreatment GLNU was prognosticator of survival.

Pre-treatment TLG had been shown to be a prognostic factor in cervical cancer [40] and ∆TLG was reported to be predictive for response to CCRT at the second week for lung cancer patients [41]. Combination of textural feature and TLG could serve as a risk-stratification strategy in oropharyngeal cancer [9]. In the present study, the combination of pretreatment GLNU > 48 and ∆TLG decline < 60% (the high risk group) predicted a recurrent risk of 92% (11/12), compared to 72% (13/18) when using ∆TLG alone. Therefore, the combination of pretreatment GLNU and ∆TLG were more powerful than ∆TLG alone to define the patients at high risk. Identifying the patients with a high risk of treatment failure as early as 2 weeks during CCRT offers the opportunity to pursue more aggressive treatment in this subgroup of patients with bulky cervical cancer.

Tumor size, as a surrogate of local tumor extension, is a very important prognostic factor to local control and survival in cervical cancer [42]. Recent report in cervical cancer patients from NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group randomized trials showed that tumor size was the most significant clinical factor by nomogram analysis [2]. Since all patients enrolled in this study were MRI-defined bulky tumor, the other clinical prognostic factors might not be able to reach statistical significance due to the limited patient number. The measurement of the tumor volume by PET images is MTV, which represents the size of highly viable tumor cells and excludes necrotic tissues. MTV has been suggested as a prognostic factor in few studies [20,43]. However, Yoo et al. showed that TLG was a more significant predictor than MTV for the recurrence of cervical cancer in multivariate analysis. Our study also supports that both MTV and ∆MTV were not significant prognostic factors in patients with bulky cervical cancer. Interestingly, Hatt et al. reported that volume and heterogeneity were independent prognostic factors and suggested that textural features and MTV may provide valuable complementary information [44].

One strength of this study is the prospective data collection and complete long-term follow up with a strong clinical relevant endpoint, overall survival. Since most of patients with recurrence died of disease, the result of progression-free survival was similar to overall survival. The success of salvage treatment was dependent on the location of recurrent tumors. Three of four salvaged patients (3 high risk and 1 low risk) had recurrent disease limited to supraclavicular or para-aortic lymph nodes, in accordance to our previous report [45]. In this study, eleven of 12 patients in the high risk group suffered from disease relapse; 81% with distant metastasis. This result implies that the heterogeneity of the primary tumor could represent tumor aggressiveness, increasing the chance of distant metastasis. For high risk group, 83% (10/12) patients became non-CMR after CCRT. Patients with non-CMR had significantly worse 5-year OS rate (50%) than those with CMR (P = 0.002). Similarly, the 5-year OS rate (42%) for the high risk group was significantly worse than that for the low risk group (P = 0.001). Therefore, risk stratification by GLNU and TLG decline shows similar prognostic prediction as post-CCRT response but much earlier. This provides the opportunity to adjust individualized regimens early in the treatment course.

Our study had several limitations. Firstly, although the sample size of this prospective study was large compared to the other similar studies, it was still small and lacked a verification group. Secondly, glucose metabolism is only one aspect of tumor phenotype. Intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity cannot represent the whole picture of tumor heterogeneity. In addition, only primary tumors were selected for imaging analysis to predict survival outcomes. The prognostic value of adding the texture features of nodal metastases was not undertaken. The applications of this texture analysis in other disease status or different levels of metastasis are required further studies. Nevertheless, our study demonstrated that it was feasible to evaluate the change of tumor heterogeneity by means of molecular imaging in the course of therapy. More comprehensive assessment of the molecular features of patients based on tumor specimen characterization and noninvasive molecular imaging approaches are required for clinical trials in the era of precision medicine [46].

Conclusion

Our results propose a two-step strategy by 18F-FDG PET to stratify the risk of patients with bulky cervical cancer. Patients with high pretreatment GLNU, which represents higher intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity, can be identified. If these patients have a poor treatment response shown by a small TLG decline at 2 weeks during CCRT, they are identified as a high risk group with worse survival outcomes. This gives the opportunity to adjust individualized regimens early in the treatment course. Based on our preliminary results, further independent validation study should be conducted to justify a change of treatment in high risk group patients.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants CMRPG340692 and CMRPG380671 from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-Analysis Collaboration. Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 18 randomized trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:5802–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose PG, Java J, Whitney CW, Stehman FB, Lanciano R, Thomas GM, DiSilvestro PA. Nomograms Predicting Progression-Free Survival, Overall Survival, and Pelvic Recurrence in Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer Developed From an Analysis of Identifiable Prognostic Factors in Patients From NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group Randomized Trials of Chemoradiotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:2136–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.7122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang S, Nam BH, Park JY, Seo SS, Ryu SY, Kim JW, Kim SC, Park SY, Nam JH. Risk Assessment Tool for Distant Recurrence After Platinum-Based Concurrent Chemoradiation in Patients With Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer: A Korean Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:2369–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.5923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidd EA, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. The standardized uptake value for F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose is a sensitive predictive biomarker for cervical cancer treatment response and survival. Cancer. 2007;110:1738–44. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidd EA, Thomas M, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. Changes in Cervical Cancer FDG Uptake During Chemoradiation and Association with Response. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh D, Lee JE, Huh SJ, Park W, Nam H, Choi JY, Kim BT. Prognostic Significance of Tumor Response as Assessed by Sequential 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography During Concurrent Chemoradiation Therapy for Cervical Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87:549–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eary JF, O’Sullivan F, O’Sullivan J, Conrad EU. Spatial heterogeneity in sarcoma 18F-FDG uptake as a predictor of patient outcome. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1973–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.053397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tixier F, Le Rest CC, Hatt M, Albarghach N, Pradier O, Metges JP, Corcos L, Visvikis D. Intratumor Heterogeneity Characterized by Textural Features on Baseline 18F-FDG PET Images Predicts Response to Concomitant Radiochemotherapy in Esophageal Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:369–78. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.082404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng NM, Dean Fang YH, Tung-Chieh Chang J, Huang CG, Tsan DL, Ng SH, Wang HM, Lin CY, Liao CT, Yen TC. Textural Features of Pretreatment 18F-FDG PET/CT Images: Prognostic Significance in Patients with Advanced T-Stage Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1703–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.119289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng NM, Fang YH, Lee LY, Chang JC, Tsan DL, Ng SH, Wang HM, Liao CT, Yang LY, Hsu CH, Yen TC. Zone-size nonuniformity of 18F-FDG PET regional textural features predicts survival in patients with oropharyngeal cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:419–28. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2933-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook GJ, Yip C, Siddique M, Goh V, Chicklore S, Roy A, Marsden P, Ahmad S, Landau D. Are Pretreatment 18F-FDG PET Tumor Textural Features in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Associated with Response and Survival After Chemoradiotherapy? J Nucl Med. 2013;54:19–26. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.107375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidd EA, Grigsby PW. Intratumoral Metabolic Heterogeneity of Cervical Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14:5236–41. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung HH, Kang SY, Ha S, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Cheon GJ. Prognostic value of preoperative intratumoral FDG uptake heterogeneity in early stage uterine cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27:e15. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook GJ, O’Brien ME, Siddique M, Chicklore S, Loi HY, Sharma B, Punwani R, Bassett P, Goh V, Chua S. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Erlotinib: Heterogeneity of F-FDG Uptake at PET-Association with Treatment Response and Prognosis. Radiology. 2015;276:883–93. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015141309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bundschuh RA, Dinges J, Neumann L, Seyfried M, Zsótér N, Papp L, Rosenberg R, Becker K, Astner ST, Henninger M, Herrmann K, Ziegler SI, Schwaiger M, Essler M. Textural Parameters of Tumor Heterogeneity in 18F-FDG PET/CT for Therapy Response Assessment and Prognosis in Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:891–7. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.127340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang F, Thomas MA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. Temporal analysis of intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity characterized by textural features in cervical cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:716–27. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2332-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delbeke D, Coleman RE, Guiberteau MJ, Brown ML, Royal HD, Siegel BA, Townsend DW, Berland LL, Parker JA, Hubner K, Stabin MG, Zubal G, Kachelriess M, Cronin V, Holbrook S. Procedure Guideline for Tumor Imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT 1.0. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:885–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chou HH, Chang HP, Lai CH, Ng KK, Hsueh S, Wu TI, Chen MY, Yen TC, Hong JH, Chang TC. 18F-FDG PET in stage IB/IIB cervical adenocarcinoma/adenosquamous carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:728–35. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA. From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving Considerations for PET Response Criteria in Solid Tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:122S–50S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller TR, Grigsby PW. Measurement of tumor volume by PET to evaluate prognosis in patients with advanced cervical cancer treated by radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:353–9. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02705-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larson SM, Erdi Y, Akhurst T, Mazumdar M, Macapinlac HA, Finn RD, Casilla C, Fazzari M, Srivastava N, Yeung HW, Humm JL, Guillem J, Downey R, Karpeh M, Cohen AE, Ginsberg R. Tumor Treatment Response Based on Visual and Quantitative Changes in Global Tumor Glycolysis Using PET-FDG Imaging: The Visual Response Score and the Change in Total Lesion Glycolysis. Clin Positron Imaging. 1999;2:159–71. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(99)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horng-Hai L, Jia-Guu L, Luo RC. The analysis of natural textures using run length features. IEEE T Ind Electron. 1988;35:323–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chicklore S, Goh V, Siddique M, Roy A, Marsden P, Cook GR. Quantifying tumour heterogeneity in 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging by texture analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:133–40. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang YH, Lin CY, Shih MJ, Wang HM, Ho TY, Liao CT, Yen TC. Development and evaluation of an open-source software package “CGITA” for quantifying tumor heterogeneity with molecular images. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:248505. doi: 10.1155/2014/248505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai CS, Lai CH, Chang TC, Yen TC, Ng KK, Hsueh S, Hsueh S, Lee SP, Hong JH. A Prospective Randomized Trial to Study the Impact of Pretreatment FDG-PET for Cervical Cancer Patients With MRI-Detected Positive Pelvic but Negative Para-Aortic Lymphadenopathy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:477–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundberg M, Grimby-Ekman A, Verbunt J, Simmonds MJ. Pain-related fear: a critical review of the related measures. Pain Res Treat. 2011;2011:494196. doi: 10.1155/2011/494196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. Association of posttherapy positron emission tomography with tumor response and survival in cervical carcinoma. JAMA. 2007;298:2289–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siva S, Herschtal A, Thomas JM, Bernshaw DM, Gill S, Hicks RJ, Narayan K. Impact of post-therapy positron emission tomography on prognostic stratification and surveillance after chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:3981–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beriwal S, Kannan N, Sukumvanich P, Richard SD, Kelley JL, Edwards RP, Olawaiye A, Krivak TC. Complete metabolic response after definitive radiation therapy for cervical cancer: Patterns and factors predicting for recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:303–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. Metabolic Response on Post-therapy FDG-PET Predicts Patterns of Failure After Radiotherapy for Cervical Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:185–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onal C, Reyhan M, Guler OC, Yapar AF. Treatment outcomes of patients with cervical cancer with complete metabolic responses after definitive chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:1336–42. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onal C, Guler OC, Reyhan M, Yapar AF. Prognostic value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in pelvic lymph nodes in patients with cervical cancer treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.01.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brooks FJ, Grigsby PW. Current measures of metabolic heterogeneity within cervical cancer do not predict disease outcome. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, Parmar C, Grossmann P, Carvalho S, Bussink J, Monshouwer R, Haibe-Kains B, Rietveld D, Hoebers F, Rietbergen MM, Leemans CR, Dekker A, Quackenbush J, Gillies RJ, Lambin P. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4006. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong JH, Chen MS, Lin FJ, Tang SG. Prognostic assessment of tumor regression after external irradiation for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:913–7. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90787-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrandina G, Macchia G, Legge F, Deodato F, Forni F, Digesù C, Carone V, Morganti AG, Scambia G. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma undergoing preoperative radiochemotherapy: association with pathological response to treatment and clinical outcome. Oncology. 2008;74:42–9. doi: 10.1159/000138979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juweid ME, Cheson BD. Positron-emission tomography and assessment of cancer therapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:496–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ben-Haim S, Ell P. 18F-FDG PET and PET/CT in the evaluation of cancer treatment response. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:88–99. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.054205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks FJ, Grigsby PW. The Effect of Small Tumor Volumes on Studies of Intratumoral Heterogeneity of Tracer Uptake. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:37–42. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.116715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoo J, Choi JY, Moon SH, Bae DS, Park SB, Choe YS, Lee KH, Kim BT. Prognostic significance of volume-based metabolic parameters in uterine cervical cancer determined using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:1226–33. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318260a905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Usmanij EA, de Geus-Oei LF, Troost EG, Peters-Bax L, van der Heijden EH, Kaanders JH, Oyen WJ, Schuurbiers OC, Bussink J. 18F-FDG PET early response evaluation of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with concomitant chemoradiotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1528–34. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.116921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Nene SM, Camel HM, Galakatos A, Kao MS, Lockett MA. Effect of tumor size on the prognosis of carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with irradiation alone. Cancer. 1992;69:2796–806. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920601)69:11<2796::aid-cncr2820691127>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim BS, Kim IJ, Kim SJ, Nam HY, Pak KJ, Kim K, Yun MS. The Prognostic Value of the Metabolic Tumor Volume in FIGO stage IA to IIB Cervical Cancer for Tumor Recurrence: Measured by F-18 FDG PET/CT. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;45:36–42. doi: 10.1007/s13139-010-0062-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatt M, Majdoub M, Vallieres M, Tixier F, Le Rest CC, Groheux D, Hindié E, Martineau A, Pradier O, Hustinx R, Perdrisot R, Guillevin R, El Naqa I, Visvikis D. 18F-FDG PET Uptake Characterization Through Texture Analysis: Investigating the Complementary Nature of Heterogeneity and Functional Tumor Volume in a Multi-Cancer Site Patient Cohort. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:38–44. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.144055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ho KC, Wang CC, Qiu JT, Lai CH, Hong JH, Huang YT, Huang KG, Chao A, Lin G, Yen TC. Identification of prognostic factors in patients with cervical cancer and supraclavicular lymph node recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:253–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seoane J, De Mattos-Arruda L. The challenge of intratumour heterogeneity in precision medicine. J Nucl Med. 2014;276:41–51. doi: 10.1111/joim.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.