Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, pruritic skin disease often complicated by bacterial superinfection affecting 10.7% of American children. The pathogenesis involves a skin barrier breakdown in addition to dysfunctional innate and adaptive immune response, including an unbalanced increase in T-helper 2 cells and hyperimmunoglobulinemia E. The increased numbers of T-helper 2 cells are involved in stimulating the production of immunoglobulin E and eosinophilia by releasing interleukin-4, -5, and -13 as well as in decreasing protection against bacterial superinfection by releasing interleukin-10. The current Food and Drug Administration-approved symptomatic treatment for AD includes topical ointments, topical and systemic corticosteroids, topical immunomodulant therapy, antibiotics, and phototherapy, but there are not approved targeted therapies or cures. By presenting a case of an 8-year-old African-American boy, this case report supports novel therapy of moderate-to-severe AD with apremilast, a phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibitor. Apremilast has recently completed the phase 2 clinical trial (NCT02087943) for treatment of AD in adults. This case report illustrates the potential for apremilast as a treatment for AD in children, where there is a great need for safe and effective medications.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Atopic eczema, Atopy, Pediatric dermatology, Apremilast

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, pruritic skin disease often complicated by bacterial superinfection affecting 10.7% of American children [1]. The pathogenesis involves a skin barrier breakdown in addition to dysfunctional innate and adaptive immune response, including an unbalanced increase in T-helper 2 (Th2) cells and hyperimmunoglobulinemia E [2]. The increased numbers of Th2 cells are involved in stimulating the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) and eosinophilia by releasing interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13 and in decreasing protection against bacterial superinfection by releasing IL-10. The current Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved symptomatic treatment for AD includes topical ointments, topical and systemic corticosteroids, topical immunomodulant therapy, antibiotics, and phototherapy, but there are not FDA-approved targeted therapies or cures [2]. Many physicians resort to off-label use of systemic immunomodulating therapy such as cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and azathioprine. There is a large unmet need for safe medications to treat severe, recalcitrant AD, especially in children.

Apremilast is a phosphodiesterase type 4 (PDE4) inhibitor indicated for treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis [3]. Apremilast has recently completed the phase 2 clinical trial (NCT02087943) for use in treatment of AD in adults. Patients with AD were demonstrated to have increased activity of phosphodiesterase in their leukocytes compared to controls, which is an important mechanism of inflammation in AD [4, 5, 6, 7]. Here, we describe a child with severe AD who failed traditional therapy but had a favorable response to apremilast therapy.

Case Presentation

An 8-year-old African-American male with a past medical history of asthma and environmental and food allergies presented for follow-up appointment to the dermatologist with a persistent rash located on the upper and lower extremities, trunk, neck, and scalp. The rash was pruritic, lichenified, and crusting and had been present and severe in quality for years despite therapy escalation by the dermatologist as described below. Two years prior, when he first presented to the dermatologist, he was adhering to a regimen of tacrolimus ointment and desonide topical cream from his allergist, which showed only minimal improvement in the lesions and pruritus. His laboratory data included an IgE level of 11,769 IU/ml (normal range 0–90) and an eosinophil percentage of leukocytes relatively increased at 8.1% (normal range 0–7) but absolutely normal at 0.44 × 103/μl (normal range 0.0–0.5). He also had a strong family history of AD since both of his parents had been diagnosed with atopic dermatitis as children. At that time, the dermatologist clinically diagnosed the child with AD based on his erythematous, eczematous patches, and lichenification that covered 60% of his body surface area (table 1). No biopsies were performed because they are not recommended for diagnosis of AD. At the time of first presentation, there were also honey-colored crusting suggesting bacterial superinfection and abscesses on the neck (fig. 1a). He was prescribed trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 2 weeks. With these signs of infection, systemic immunosuppression for AD control was deferred until the infection cleared. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% topical ointment b.i.d. and advised to continue using desonide on his face, groin, and armpit. Two months later, when the infection had resolved, more aggressive treatment was prescribed, including prednisone 20 mg, myophenolate mofetil 200 mg/ml topical for his body, and tacrolimus topical for his face.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for AD

| American Academy of Dermatology [13] | Hanifin's and Rajka's criteria [14] |

|---|---|

| Essential features (must be present) | Major criteria (must have 3) |

| Pruritus | Pruritus |

| Eczema (acute, subacute, chronic) | Dermatitis affecting flexural surfaces in adults or face and extensor surfaces in infants |

| Typical morphology and age-specific patternsa | Chronic or relapsing dermatitis |

| Chronic or relapsing history | Personal or family history of cutaneous or respiratory allergy |

| Important features | Minor criteria (must have 3) |

| Early age of onset | Facial features (infraorbital darkening, etc.) |

| Atopy | Triggers (environmental factors, etc.) |

| Personal and/or family history | Complications (susceptibility to skin infections, etc.) |

| IgE reactivity | Other (early age of onset, dry skin, etc.) |

| Xerosis |

Patterns include: facial, neck, and extensor involvement in infants and children; current or prior flexural lesions in any age group, and sparing of groin and axillary regions.

Fig. 1.

Clinical appearance before and during therapy with apremilast. a Neck abscesses on presentation at 6 years of age. b Patient after treatment with topical immunosuppressant medications and systemic corticosteroids. c Patient before apremilast treatment. d Patient 8 weeks after apremilast use.

Seven months after treatment escalation with immunosuppressive therapy, 50% of the body surface was still covered with the same extremely pruritic rash (fig. 1b). The patient was started on omalizumab 300-mg injections for asthma every 2 weeks with the hope that these injections might also improve his other atopic conditions, including AD. Five months after these injections at 8 years of age, the patient was prescribed off-label treatment with apremilast 30 mg daily, half the adult dose of 30 mg twice daily, because his skin was still exhibiting excoriation, hyperpigmentation, and intense pruritus (fig. 1c). Apremilast provided quick and long-lasting relief of his intense pruritus in as little as 2 weeks with no adverse effects. His hair has started growing back over his scalp lesions, and the lesions over the rest of his body demonstrated significantly less inflammation and excoriation (fig. 1d).

Discussion

Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases are a group of eleven isoenzymes that break down the second messengers cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) into inactive molecules, decreasing the intracellular levels. In AD specifically, the increased activity of phosphodiesterase creates a proinflammatory state by further decreasing cyclic nucleotides [4,5,6,7,8]. Abnormally low levels of cyclic nucleotides may lead to elevated levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which reduces interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and also may lead to increased IL-4, which simulates Th2 cells [9, 10]. Th2 cells release IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which are involved in stimulating the production of IgE and eosinophilia. The release of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, also involved in the Th2 immune response is thought to increase the frequency of bacterial superinfection of AD lesions.

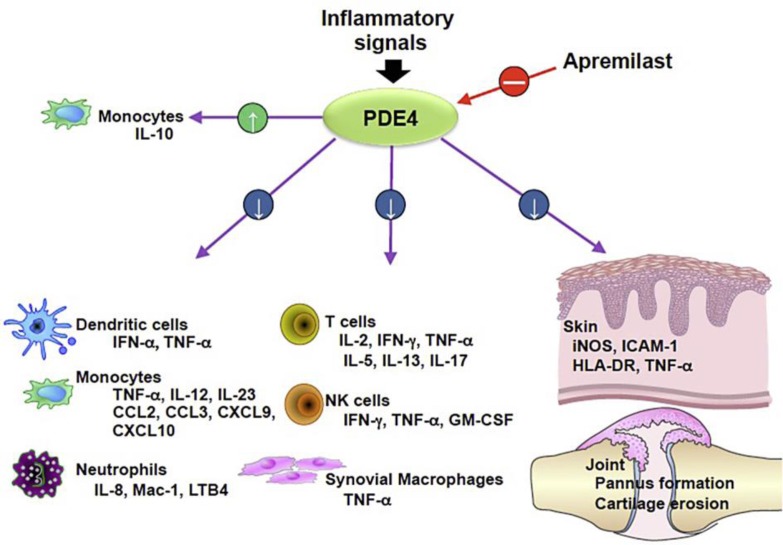

The exact mechanism of how apremilast works for AD patients is unknown, but by inhibiting the increased activity of phosphodiesterase, perhaps the hyperactivity of the immune system in AD can be dialed back to baseline [4]. Apremilast specifically inhibits PDE4, which is found in keratinocytes and a variety of leukocytes of the innate and adaptive immune system, including Langerhans cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, T helper cells, and eosinophils [4, 8, 11]. Inhibiting PDE4 increases levels of cAMP in leukocytes, which decreases the number of proinflammatory cytokines and augments the activity of an anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 [4, 8]. By targeting a wide variety of cells, apremilast has been found in in vivo and in vitro studies to modulate levels of important mediators of inflammatory reactions (fig. 2). Apremilast decreases IL-12 and IL-23 release from monocytes, which normally stimulate the T-helper 1 and T-helper 17 cells, respectively [4, 11, 12]. In addition, it decreases PGE2, which may decrease the Th2 cell response. Thus, the mediators of inflammation released by T helper cells are suppressed, including IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) from Th1 cells, IL-4 and IL-13 from Th2 cells, and IL-17 and IL-22 from Th17 cells [11]. These cytokines, most notably IL-4 and IL-17, go on to stimulate keratinocytes to produce IL-31, which stimulates pruritus [12]. Thus, by decreasing the Th2 and Th17 immune response, pruritus is also decreased.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of PDE4 by apremilast affects leukocytes and keratinocytes by modulating the release of inflammatory mediators thought to trigger the inflammatory reaction of AD. Figure reproduced with permission from Celgene Corporation.

The value of apremilast over currently available oral medications for moderate-to-severe AD is that it is safe with diarrhea, nausea, upper respiratory infection, and headache being the most frequently reported side effect and no known end-organ damage [4, 12]. In addition, as was demonstrated in clinical trials for psoriasis with apremilast, pruritus and quality of life greatly improve with use in AD [4]. Of note, another biologic with similar targeted treatment of AD named dupilumab is a monocolonal antibody that binds the alpha subunit of the IL-4 receptor and inhibits the promotion of the Th2 response by IL-4 and IL-13 [12]. Currently in phase 3 clinical trial (NCT02277769), dupilumab shows promise of being the first FDA-approved targeted therapy for treating the symptoms of moderate-to-severe AD in adults [12]. With more targeted therapies, the aim is that the adverse effects of therapy for moderate-to-severe AD will be diminished and compliance and efficacy will be increased.

Conclusion

AD is a chronic disease with no cure and ineffective FDA-approved treatments for moderate-to-severe disease. Clinicians are in need of safe treatment options to ameliorate the symptoms of AD, especially for children. With future clinical studies and feedback from dermatologists in the pediatric population, apremilast could prove to be an effective medication to decrease the intense pruritus and inflammation of skin lesions.

Statement of Ethics

The patient's parent gave written informed consent.

Disclosure Statement

Rachael Saporito has no relevant relationships to disclose with industry. David Cohen, MD, is an Advisor, Speaker, and Clinical Researcher for Celgene Corporation.

References

- 1.Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children's Health. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:67–73. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung TN, Hon KL. Eczema therapeutics in children: what do the clinical trials say? Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21:251–260. doi: 10.12809/hkmj144474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdulrahim H, Thistleton S, Adebajo AO, Shaw T, Edwards C, Wells A. Apremilast: a PDE4 inhibitor for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:1099–1108. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1034107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samrao A, Berry TM, Goreshi R, Simpson EL. A pilot atudy of an oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor (apremilast) for atopic dermatitis in adults. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:890–897. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grewe SR, Chan SC, Hanifin JM. Elevated leukocyte cyclic AMP-phosphodiesterase in atopic disease: a possible mechanism for cyclic AMP-agonist hyporesponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982;70:452–457. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(82)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan SC, Reifsnyder D, Beavo JA, Hanifin JM. Immunochemical characterization of the distinct monocyte cyclic AMP-phosphodiesterase from patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;91:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanifin JM, Chan SC. Monocyte phosphodiesterase abnormalities and dysregulation of lymphocyte function in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105((suppl)):84S–88S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12316116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moustafa F, Feldman SR. A review of phosphodiesterase-inhibition and the potential role for phosphodiesterase 4-inhibitors in clinical dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams M, Horan G, Schafer PH. 24th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress; 7–11 October; Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 10.Chan SC, Kim JW, Henderson WR, Jr, Hanifin JM. Altered prostaglandin E2 regulation of cytokine production in atopic dermatitis. J Immunol. 1993;151:3345–3352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schafer PH, Parton A, Gandhi AK, et al. Apremilast, a cAMP phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, demonstrates anti-inflammatory activity in vitro and in a model of psoriasis. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:842–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notaro ER, Sidbury R. Systemic agents for severe atopic dermatitis in children. Paediatr Drugs. 2015;17:449–457. doi: 10.1007/s40272-015-0150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1980;92:44–47. [Google Scholar]