Abstract

Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction, although rare in children, is a significant cause of portal hypertension (PHT) leading to life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding in the pediatric age group. PHT may also lead to other complications such as hyperesplenism, cholangyopathy, ascites, and even hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension that may require organ transplantation. Herein we report the case of an asymptomatic 11-month-old infant wherein a hepatomegaly and cavernous transformation of the portal vein was detected by liver ultrasound. Neither signs of thrombosis in arteriovenous system, nor affectation of biliary tract were identified in the magnetic resonance imaging study. A significant enlargement of the caudate lobe of the liver was reported. No risk factors were detected. The differential diagnosis performed was extensive. Inherited thrombophilia and storage disorders were especially considered. Liver biopsy was normal. Upper gastrointestinal esophagogastroduodenoscopy detected two small varicose cords on the distal third of the esophagus. Finding a cavernous transformation of the portal vein with evidence of collateral circulation in such an early age is a challenging condition for professionals, since PHT may lead to severe complications during childhood and can compromise growth and development. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of PHT in adults have been published. However, follow-up and treatment of pediatric patients have not yet been standardized. Moreover, management of PHT in infants faces particular difficulties such as technical restrictions that could hinder their treatment.

Keywords: Cavernous transformation of portal vein, Esophageal varices, Infant, Follow-up guidelines

Introduction

Portal hypertension (PHT) and its complications during childhood represent important clinical problems that lead to significant morbidity and mortality [1]. The differential diagnosis in pediatric PHT is quite heterogeneous. Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) is one of the most common causes of PHT in children. In the prehepatic obstruction of portal vein, collaterals attempt to bypass the blockage and enter directly into the liver at the porta hepatis shaping a cavernous transformation. The obstructed portal vein is replaced by a network of hepatopetal collateral veins that connect the patent portion of the vein upstream to the patent portion downstream. Despite the formation of a significant collateral network, PHT persists as a result of increased cardiac output and decreased splanchnic arteriolar tone. Neonatal omphalitis, catheterization of the umbilical vein, pylephlebitis related to appendicitis or other intra-abdominal infections should be assessed when an EHPVO is detected. However, its etiology remains obscure in more than 65% of cases [2].

Cirrhosis, either of hepatocellular or biliary origin, is the most common cause of intrahepatic PHT. Hepatocellular causes of cirrhosis include α1-antitrypsin deficiency, autoimmune hepatitis, infectious hepatitis, metabolic diseases and toxins. Biliary causes include biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, congenital hepatic fibrosis, Caroli's disease and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Budd-Chiari syndrome results from the obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow including the inferior vena cava and/or hepatic veins. This can be due to webs of thrombi in these vessels, although it has also been associated with tumors and myeloproliferative or hypercoagulable states.

Case Report

An asymptomatic 11-month-old female infant presented with a moderate enlargement of the left lobe of the liver in a routine medical examination.

The child was born at term from Spanish, non-consanguineous and healthy parents. No choluria, acholia or pruritus was referred. The infant's anthropometry was normal. Examination showed no jaundice, bruising, petechiae or vascular spiders. Congestion of the hemorrhoid plexus was not detected. There were no signs of heart insufficiency.

An urgent liver ultrasound with Doppler study was performed showing a hepatomegaly with a significant growth of the caudate lobe and tortuous vessels in the porta hepatis with hepatopetal flow (fig. 1), congruent with a cavernous transformation of the portal vein. Ultrasonography did not uncover liver echoestructure abnormalities or ascites. Hepatic and splenic arteries, suprahepatic veins and biliary tract showed normal structure and flow, without signs of thrombosis, arteriovenous fistulas or biliary ectasia. The spleen was mildly enlarged for her age (8 cm), and a patency of the spleen-portal axis was detected. Magnetic resonance imaging techniques confirmed the cavernous transformation of the portal vein and showed peripancreatic and perisplenic collateral circulation (fig. 2), suggesting PHT. Neither signs of thrombosis in the arteriovenous system nor affectation of the biliary tract were identified.

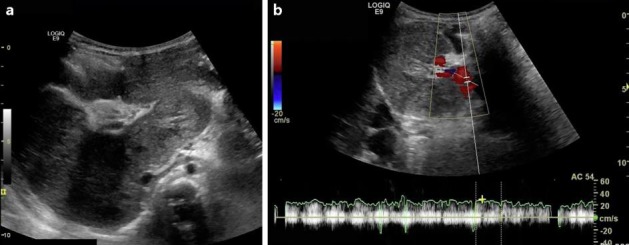

Fig. 1.

Abdominal ultrasound revealed hepatomegaly with hypertrophy of caudate lobe and a cavernous transformation of portal vein (a). The Doppler study confirmed the patency of portal vein and its hepatopetal flow (b).

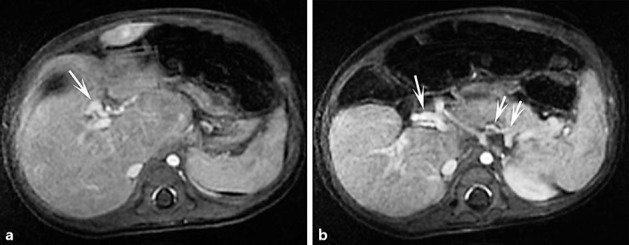

Fig. 2.

Dynamic MRI study at early portal phase displaying a heterogeneous enhancement of hepatic parenchyma, together with intrahepatic vascular prominences corresponding to portal cavernomatosis (arrow; a). Dynamic MRI study at late phase showing collateral peripancreatic and perisplenic circulation (arrows; b).

Laboratory tests showed no signs of hypersplenism, such as cytopenia. A slight hypertransaminasemia (GPT/ALT 59 U/l, GOT/AST 82 U/l) and cholestasis (GGT 92 IU/l), but normal bilirubin and alkaline phosphatases were detected. Glucose, clotting test, total proteins, albumin and lipids were normal. Alphafetoprotein remained unaltered. Protein C and S and antithrombin III deficiencies, G20210A and factor V Leiden mutations, methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase and lupus anticoagulant were discarded.

Intrahepatic disorders such as autoimmune hepatitis and infections by hepatotropic viruses (hepatitis virus A, B and C, toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, human herpesvirus 6 and Epstein-Bar virus) were assessed. Serological surveys showed normal results. The Mantoux test was negative. Cystic fibrosis and α1-antitrypsin deficiency were discarded; the α1-antitrypsin phenotype was MM. In order to assess inborn errors of metabolism, especially hepatorenal tyrosinemia, different studies were performed. Ammonia was repeatedly normal, as well as serum and urine amino acid and urine organic acid profile. Eye examination did not detect red cherry spot on the retina, lens opacities or back embryotoxon.

Given the size of the liver and the slight increase in transaminases, storage diseases (glycogenosis VI and IX, hemochromatosis and Wilson disease) were especially considered. Iron, serum copper and ceruloplasmin as well as 24-hour urine copper excretion were assessed. In order to evaluate liver damage and the presence of abnormal storage of glycogen, iron or copper, an ultrasound-guided liver biopsy was performed. No signs of cirrhosis were observed. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid Schiff, diastase periodic acid Schiff and Gomori trichrome stains were performed obtaining normal results.

An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed in order to evaluate the extension of collateral circulation. Two small varices were detected on the distal third of the esophagus. They flattened with insufflation, and no red wale markings were observed (fig. 3).

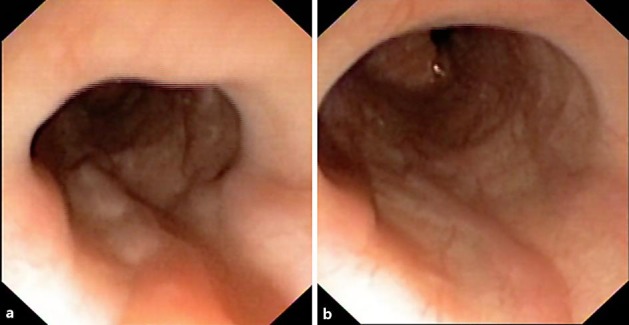

Fig. 3.

Esophagoscopy revealed two minimally protruding and slightly tortuous small varices. They showed no red wale signs (a) and were partially flattened with insufflation (b).

Discussion

While clinical guidelines for follow-up and treatment of PHT in adults have been published [3, 4], similar directives for pediatric patients are lacking, and most recommendations are based on opinions by pediatric experts, case series or cohorts [2, 5].

Flores-Calderón et al. [2] state that esophagogastroduodenoscopy should be performed in every suspected case of PHT in children to screen for esophageal and gastric varices. Data about risk factors for bleeding in children with esophageal varices are lacking [6]. In consequence, the proper time when a new upper endoscopy should be repeated before first bleeding is not well defined. The selection of high-risk patients represents a clinical challenge for the hepatologist in order to reduce futile examinations, related costs and patients’ burden. In this regard, different studies have attempted to identify ultrasonographic predictors of esophageal varices in children and adolescents with EHPVO. Additionally, the role of capsule endoscopy as a minimally invasive tool for the screening of esophageal varices in children is under evaluation. Extrapolating from adults and taking the natural course of the disease into consideration, it should be carried out every 1–2 years in children with small varices without history of bleeding [2].

Adult patients with small varices with red wale marks or Child C class have an increased risk of bleeding and should be treated with nonselective β-blockers [4]. Since there are no randomized trials assessing the efficacy of nonselective β-blockers (such as propranolol) in children, there is not enough information to recommend their use in this group as a prevention of first bleeding episode [2]. In adult patients with medium-large varices, nonselective β-blockers or endovariceal ligation is recommended for the prevention of the first variceal bleeding. The choice of treatment should be based on local resources and expertise, characteristics, side effects and contraindications [4]. Because of lack of trials, the role of prophylactic endovariceal ligation is still controversial in children. Those with large varices should be considered for a prophylactic endoscopic procedure on a case-by-case basis. Below 1 year of age, endoscopic variceal ligation is not feasible because the devices available cannot be used with small pediatric endoscopes. Therefore, although sclerotherapy has been abandoned worldwide as a prophylactic endoscopic procedure, it should be considered in these patients [7].

With respect to the meso-Rex bypass procedure, controversy exists with regard to the legitimacy of its utilization in an asymptomatic child, including those who have not yet had a variceal bleed. One approach suggests the assessment of the feasibility of surgery in all children with EHPVO and PHT [8], while another defers surgery until clear and significant associated disease is established.

In conclusion, there is paucity of data to guide the follow-up and management of complications of PHT in children. Special emphasis should be placed on the management of PHT in infants in whom a steady damage may lead to great morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, the available tools are scarce in this group of age.

Statement of Ethics

The authors state that the patient's family has given consent for this publication.

Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Grimaldi C, de Ville de Goyet J, Nobili V. Portal hypertension in children. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:260–261. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores-Calderón J, Morán-Villota S, Solange-Heller R, Nares-Cisneros J, Zárate-Mondragón F, González-Ortiz B, Chávez-Barrera JA, Vázquez-Frías R, Martínez-Marín EJ, Marín-Rentería N, Bojórquez-Ramos MC, Castillo-De León YA, Ortiz-Galván RC, Varela-Fascinetto G. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) in children. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:1.s3–s24. doi: 10.1016/S1665-2681(19)31403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W, Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922–938. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Franchis R, Baveno V Faculty Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shneider BL, Bosch J, de Franchis R, Emre SH, Groszmann RJ, Ling SC, Lorenz JM, Squires RH, Superina RA, Thompson AE, Mazariegos GV, Expert Panel of the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC Portal hypertension in children: expert pediatric opinion on the report of the Baveno V Consensus Workshop on Methodology of Diagnosis and Therapy in Portal Hypertension. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:426–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alcantara RV, Yamada RM, De Tommaso AM, Bellomo-Brandão MA, Hessel G. Non-invasive predictors of esophageous varices in children and adolescents with chronic liver disease or extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. J Pediatr. 2012;88:341–346. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Antiga L. Medical management of esophageal varices and portal hypertension in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012;21:211–218. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Ville de Goyet J, D'Ambrosio G, Grimaldi C. Surgical management of portal hypertension in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012;21:219–232. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]