Abstract

Motivation: The growing amount of regulatory data from the ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics and other consortia provides a wealth of opportunities to investigate the functional impact of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Yet, given the large number of regulatory datasets, researchers are posed with a challenge of how to efficiently utilize them to interpret the functional impact of SNP sets.

Results: We developed the GenomeRunner web server to automate systematic statistical analysis of SNP sets within a regulatory context. Besides defining the functional impact of SNP sets, GenomeRunner implements novel regulatory similarity/differential analyses, and cell type-specific regulatory enrichment analysis. Validated against literature- and disease ontology-based approaches, analysis of 39 disease/trait-associated SNP sets demonstrated that the functional impact of SNP sets corresponds to known disease relationships. We identified a group of autoimmune diseases with SNPs distinctly enriched in the enhancers of T helper cell subpopulations, and demonstrated relevant cell type-specificity of the functional impact of other SNP sets. In summary, we show how systematic analysis of genomic data within a regulatory context can help interpreting the functional impact of SNP sets.

Availability and Implementation: GenomeRunner web server is freely available at http://www.integrativegenomics.org/.

Contact: mikhail.dozmorov@gmail.com

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

The success of genome-wide association studies (GWASs) in finding causative single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for Mendelian disorders is hindered by their failure to define complex patterns of non-Mendelian inheritance, such as seen in multi-factorial complex diseases (Altmuller et al., 2001). This is in part because ∼88–93% of all SNPs lie outside protein coding regions (Hindorff et al., 2009; Maurano et al., 2012), complicating our understanding of the regulatory mechanisms involved. Furthermore, ∼90% of all SNPs are rare (Nelson et al., 2012), i.e. occurring in a small percentage of individuals (typically 0.05–5%), and generally underemphasized in GWASs. Thus, only a fraction of valuable genetic information is studied.

Recent research has provided evidence that rare SNPs and SNPs outside of protein-coding regions can contribute to disease manifestation (Battle et al., 2014; Bodmer and Bonilla, 2008; Cheung and Spielman, 2009; Corradin et al., 2014; Morley et al., 2004; Reddy et al., 2012) by collectively altering DNA methylation (Gertz et al., 2011), histone modifications (McDaniell et al., 2010; Trynka et al., 2013), enhancers (Corradin et al., 2014), chromatin states (Kasowski et al., 2013; Kilpinen et al., 2013), deoxyribonuclease I (DNAse I) accessibility (Degner et al., 2012) and transcription factor binding (Kasowski et al., 2010; Maurano et al., 2012, 2015; Reddy et al., 2012), leading to gene expression changes (Battle et al., 2014; Cheung and Spielman, 2009; Morley et al., 2004; Stranger et al., 2007) (reviewed in Haraksingh and Snyder, 2013) and disruption of protein–protein interactions (Mosca et al., 2015). Yet exploring SNPs-regulatory relationships in a hypothesis-driven manner is not just time-consuming, but also limited to the regulatory mechanisms an individual researcher can think of. Conversely, using systematically organized publicly available regulatory data offers a data-driven investigation of potential functional mechanisms altered by SNPs. To do this, software is needed to facilitate systematic analysis of such genome-wide data.

Recent years have seen rapid growth of publicly available data on genome organization and functional/regulatory information (Adams et al., 2012; Bernstein et al., 2010; ENCODE Project Consortium, 2004). The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project, the Roadmap Epigenomics program and others (Adams et al., 2012; Bernstein et al., 2010; ENCODE Project Consortium, 2004) have been actively cataloguing functional/regulatory genome annotation datasets, such as cell- and tissue specific histone modification profiles, DNAse I hypersensitive sites, chromatin states, and transcription factor-binding sites (TFBSs). Although many breakthroughs have been made by the analyses of these datasets, these resources remain underutilized by computational biologists for systematic analysis and interpretation of the functional mechanisms associated with, and potentially altered by, experimentally obtained ‘omics’ data.

In this article, we describe the GenomeRunner web server—an automated framework for the statistical analysis and interpretation of the functional impact of SNP sets using regulatory datasets from the ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics and other projects. GenomeRunner prioritizes regulatory datasets most significantly enriched in SNP sets and visualizes the most significant enrichments (Fig. 1), thus suggesting regulatory mechanisms that may be altered by them. In addition to prioritizing SNP set-specific regulatory enrichments (functional impact), GenomeRunner implements three novel approaches: (i) regulatory similarity analysis, aimed at identifying groups of SNP sets having similar functional impact; (ii) differential regulatory analysis, developed to identify functional impact specific for a group of SNP sets; and (iii) cell type regulatory enrichment analysis, designed to identify cell type specificity of the functional impact. We have reviewed 20-related software tools to highlight the novel functionality of GenomeRunner (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1).

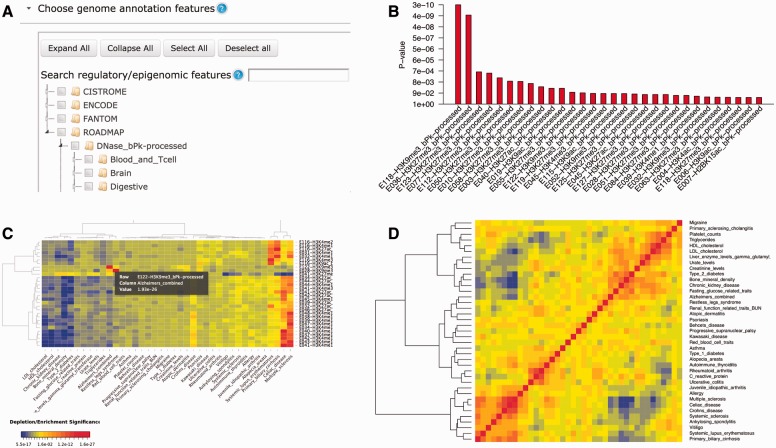

Fig. 1.

Overview of the GenomeRunner web server. (A) Hierarchical database organization. The data are organized as a ‘Source/Category/Tier or Cell Type’ hierarchy; (B) Barplot of the enrichment results. Each bar shows most significant enrichment P-values (Y axis) of a SNP set in regulatory datasets (X axis); (C) Heatmap of the enrichment results. Each cell shows color-coded enrichment P-values of the top 30 regulatory datasets (rows) most variably enriched across SNP sets (columns). Blue/red gradient highlights depletion/enrichment significance; (D) Regulatory similarity correlogram showing clustered matrix of pairwise correlation coefficients among SNP set-specific regulatory enrichment profiles, with blue/red gradient highlighting negative/positive correlations, respectively. All results are visualized as sortable tables, and are available for download (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

The article is organized as follows. The Methods part provides a brief overview of GenomeRunner functionality and analytical approaches. The Results part illustrates the application of GenomeRunner to deepen our understanding of the potential functional impact of 39 disease/trait-associated SNP sets. GenomeRunner identified a group of nine immunologic diseases with distinct functional enrichment signature of the corresponding SNP sets, detected cell specificity of the regulatory enrichments relevant to disease pathology, and confirmed known enrichment of the immunologic disease-associated SNP sets in T helper cell-specific enhancers, H3K4me1 and H3K27ac activating histone marks. In summary, we show how GenomeRunner, an open-source web server freely accessible at http://www.integrativegenomics.org/, aids in biological interpretation of the significance of SNP sets in terms of putative functional impact.

2 Methods

2.1 Data source and preprocessing

We used organism- and cell type-specific regulatory datasets from the ENCODE (Rosenbloom et al., 2013) and Roadmap Epigenomics (Bernstein et al., 2010) projects. The hg19/mm9 human/mouse genome annotation data from the ENCODE project were downloaded from the UCSC genome database (Rosenbloom et al., 2013) (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/encodeDCC/and http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/mm9/encodeDCC/, respectively). The Roadmap Epigenomics hg19 human genome annotation data was obtained from the http://egg2.wustl.edu/roadmap/web_portal/index.html web portal (Roadmap Epigenomics et al., 2015). The FANTOM consortium (Carninci et al., 2005) human cell type-specific enhancer data was downloaded from http://enhancer.binf.ku.dk/presets/. The Cistrome (Liu et al., 2011) human/mouse regulatory data were downloaded from http://cistrome.dfci.harvard.edu/NR_Cistrome/index.html. All data were accessed on July 22, 2015.

To automate the use of the regulatory datasets, we convert the data to 0-based BED format (http://genome.ucsc.edu/FAQ/FAQformat.html#format1.7). This conversion keeps genomic coordinates and, if available, strand and score information of regions annotated with regulatory or functional properties. We keep regulatory data across standard chromosome names, e.g. for human, 22 chromosomes, X and Y chromosomes and MT chromosome, if available. To speed up data access, the BED files are compressed and indexed by the bgzip/tabix tools (Li, 2011).

As regulatory regions can be strand-specific and/or differ in the strength/significance of signal detection, we provide an option to filter the regulatory datasets by strand and signal strength. To filter the regulatory datasets by signal strength, we estimate the 25, 50 and 75% percentiles of the full signal range. These percentiles are used as thresholds to filter out regulatory regions with signal strength below the selected percentile threshold. This filtering strategy allows focusing the analyses on regulatory regions with high signal strength.

A total of 20 877 regulatory datasets (GRCh37/hg19 genome assembly) are organized in a hierarchical structure (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table S2). Each category of the regulatory datasets can be selected, as well as the individual datasets. The structured database organization simplifies interpretation of the results by focusing the analysis on a particular category of the regulatory datasets, and further narrowing it to a cell type-specific level.

2.2 Disease- and trait-associated SNP sets

Genomic coordinates (hg19) of the 39 disease- and trait-associated SNP sets were extracted from the Supplementary Table S1 of the Farh et al. article ‘Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants’ (Farh et al., 2014).

2.3 Regulatory enrichment analysis

The regulatory enrichment analysis evaluates whether SNPs in a set are statistically significantly co-localized with the regulatory regions in a datasets. The enrichment of such co-localization is assessed using the Chi-square (default) or Binomial tests, or Monte Carlo simulations (Phipson and Smyth, 2010). We do not employ random sampling from the whole genome, as the distribution of SNPs at any given genomic region is not uniform (Ellegren et al., 2003). Instead, by default, we provide a ‘background’ of all or common (with a minor allele frequency >1%) organism-specific SNPs from the latest dbSNP database. The user has an option to provide a custom background, e.g. a set of all SNPs evaluated in a study. The ‘background’ set of SNPs is used to evaluate co-localizations that occur by chance.

Considering the fact that different types of regulatory regions are not independent (e.g. DNAse I hypersensitive sites may co-localize with H3K27ac activating histone modification mark), the regulatory enrichment P-values are corrected for multiple testing using the false discovery rate (FDR) procedure. We perform the correction on a per-cell-type basis, as each cell type has its own dependencies among different types of regulatory datasets. The enrichment analysis allows mechanistic insight into the functional impact of SNPs by prioritizing regulatory datasets most significantly enriched in user-provided SNP sets.

2.4 Regulatory similarity analysis

In the era of precision medicine, or the tailoring of treatments to patient-specific genetics, classification of patients by comparing patient-specific mutation profiles (Hofree et al., 2013; Tian et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014) is becoming an important clinical goal. GenomeRunner’s regulatory similarity analysis allows classification of multiple SNP sets by estimating similarity of their functional impact by comparing their regulatory enrichment profiles.

We define a SNP set-specific regulatory enrichment profile as a vector of enrichment Z scores obtained by testing a set of SNPs for enrichment in several regulatory datasets (Supplementary Figure S2). If sets of SNPs are co-localized with similar regulatory datasets (i.e. have similar functional impact), their regulatory enrichment profiles will be similar. On the other hand, if sets of SNPs are enriched in different regulatory datasets, their regulatory enrichment profiles will be different. Note that SNPs in the sets do not have to have exact genomic location, but instead may be co-enriched in the same regulatory regions. As such, the regulatory similarity analysis evaluates relationships among SNP sets using regulatory context as a common reference.

The results of the regulatory similarity analysis are visualized as an interactive heatmap of pairwise Spearman correlation coefficients among the SNP set-specific regulatory enrichment profiles. The heatmap is clustered to highlight groups of SNP sets with distinct regulatory signatures. The user can adjust clustering parameters, and define groups of SNP sets for the subsequent differential regulatory analysis.

2.5 Differential regulatory analysis

The differential regulatory analysis defines which regulatory signatures are associated with each group of SNP sets. For each pair of groups, the distributions of the enrichment Z-scores are compared for statistically significant differences using the Wilcoxon test. This comparison is performed for each regulatory dataset used for the enrichment analysis, and an FDR-corrected vector of P-values is collected. The differential regulatory analysis identifies regulatory datasets significantly enriched in one group but not in the other.

2.6 Cell type regulatory enrichment analysis

The cell type specific bias of the functional enrichments of a SNP set can be assessed with the cell type regulatory enrichment analysis. This analysis identifies the cell type specificity of the regulatory datasets most frequently and most significantly enriched in SNPs in this set. For each cell type, the distribution of cell type-specific regulatory enrichment Z-scores is compared with the overall distribution of the enrichment Z-scores using the Wilcoxon test.

The cell type regulatory enrichment analysis, by nature, requires a SNP set to be tested in more than five cell type-specific regulatory datasets. This is best achieved by selecting several categories of cell type-specific regulatory datasets, e.g. DNAse- and histone modification regulatory datasets from the Roadmap Epigenomics project.

2.7 Literature similarity and disease ontology analyses

To establish similarity between two disease terms, the literature-based approach uses information from public databases, such as disease-phenotype data from Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, disease-associated genes (Entrez Gene), chemical compounds (CHEMID), pharmaceuticals (FDA drug list), and Gene Ontology (GO) terms. Let A and C represent the two diseases being compared and Bn represents the set of n relationships they share. The first literature-based similarity metric is the number of shared relationships between A and C, normalized to the highest number of shared relationships A and C share with any other disease besides themselves (sharedRels). The second metric represents the number of A–C shared relationships weighted by the number of expected relationships based on the connectivity of each entity (Bn) in the shared network (obsExp). Third is the minimum mutual information between A–Bn and Bn–C terms (minMim). Fourth metric is the strength of the literature connections between them (0.8 for every sentence co-mention, 0.5 for every abstract) (directStr). Fifth is the relative overlap between A and C in terms of the number of shared relationships (relOverlap). And finally, the minimum implicit strength normalized (misn), which ranks each A−Bn and Bn–C relationship as a function of the total area under the curve for all their relationships and calculates the minimum overlap they share. This misn method will weight highly correlated diseases whose overlapping relationships tend to be comparable in strength (e.g. if ‘cell growth’ is an important concept in both A and C literatures, then it will raise their misn. If it is very important to one but minimally important to the other, then it will not contribute much to the score).

The disease ontology (DO)-based similarity method uses ‘Wang’, ‘Resnik’, ‘Rel’, ‘Jiang’ and ‘Lin’ metrics, implemented in the DOSim R package (Li et al., 2011, and references therein).

2.8 Performance optimization and assessment

GenomeRunner performs a large number of statistical calculations to obtain regulatory enrichments. We optimized statistical calculations by precalculating overlaps between each default ‘background’ SNP set and each regulatory dataset. These precalculated values represent overlaps that can occur by chance and are subsequently used in the Fisher’s exact test calculations.

To quantify the performance of GenomeRunner, we evaluated three parameters for their impact on run time: (i) the number of regulatory datasets; (ii) the number of SNP sets; (iii) the size of a SNP set. Each run time evaluation included comparing the optimized versus non-optimized statistical calculations. To evaluate the effect of the number of regulatory datasets on run time, a set of 1000 randomly selected SNPs was run for the enrichment analysis using from 100 to 1000 randomly selected regulatory datasets. To evaluate how the number of SNP sets affects run time, 10–100 sets of random SNPs, each with 1000 SNPs, were analyzed for enrichment against 1000 randomly selected regulatory datasets (Supplementary Figure S1).

2.9 Implementation and availability

The GenomeRunner web server is implemented in Python 2.7. It uses CherryPy for the web framework, Mako for web pages templating, and Celery for parallelizing analyses jobs. The enrichment analysis is built upon Kent utilities (Kuhn et al., 2013), BedTools (Quinlan and Hall, 2010), pybedtools (Dale et al., 2011), bedops (Neph et al., 2012), tabix (Li, 2011) and R (Team, 2013). The front-page interface is implemented using the Bootstrap framework and jQuery UI. The interface of the results page is implemented using the shiny R package. The heatmaps are created using D3, R/Bioconductor functionality (Team, 2013), and the dendextend R package (Galili, 2015). The GenomeRunner web server is available at http://www.integrativegenomics.org, and can be run as a command line version. It runs best in Google Chrome 29+, Firefox 26+, Safari 6+. The source code and documentation for the GenomeRunner web server is available at https://github.com/mdozmorov/genomerunner_web. The quick start guide is available at https://github.com/mdozmorov/genomerunner_web/wiki. The R/Bioconductor scripts used to perform the analysis of the 39 disease/trait associated SNP sets are available at https://github.com/mdozmorov/gwas2bed/tree/master/autoimmune/R.GR.autoimmune.

3 Results

3.1 Defining regulatory mechanisms of complex diseases

To illustrate how GenomeRunner can help to better understand regulatory mechanisms that may be altered in complex diseases, and their cell type specificity, we analyzed disease- and trait-associated SNP sets from 39 well-powered GWASs (Farh et al., 2014). These include 21 immunologic diseases, four neurologic disorders, seven metabolic traits and seven other traits (Supplementary Table S3). Our analysis of the corresponding SNP sets was aimed to answer the following questions: (i) How well can relationships among the diseases be captured by the similarity of their functional impact? (ii) Are there groups of diseases with different functional impact, and what are these regulatory differences? (iii) What is the cell specificity of the functional impact of each disease?

3.2 Genomic similarity among disease-associated SNP sets correlates with knowledge-based disease similarity

The goal of the regulatory similarity analysis is to identify similarity among diseases based on patterns of the regulatory enrichments of their corresponding SNP sets (e.g. as determined by GWAS studies). Because the regulatory similarity analysis is a novel idea, we utilized several metrics to benchmark its performance in elucidating disease similarity.

To establish a reference measure of similarity among the diseases, we used the shared genomic loci method introduced in the original publication by Farh et al. (2014). This method measures similarity by calculating the number of overlapping disease-associated loci, defined as 500 bp regions surrounding disease-associated SNPs. Larger number of overlaps suggests higher similarity between a pair of diseases. We also employed literature- and DO-based approaches to measure disease similarity (Li et al., 2011; Wren et al., 2004). Both approaches offer several metrics to measure disease similarity (see ‘Methods’ section). Although each metric has been designed to measure different aspects of disease–disease relationships, they utilize the same framework of knowledge databases and DO hierarchy. Therefore, we expected each metric to perform similarly in capturing disease similarities. The literature- and DO-based approaches can help to elucidate how well the shared genomic loci and the regulatory similarity measures reflect current knowledge about disease relationships.

The literature-based and the shared genomic loci-based measures of disease similarity were highly correlated (median Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.46, Supplementary Table S4), with the misn metric best correlating with the shared genomic loci measure (Spearman = 0.49, P-value < 1.00E-16). The DO-based similarity measures were also positively correlated with the shared genomic loci-based measures, although to a lesser extent (median Spearman correlation 0.30). These results suggest that the shared genomic loci method can capture similarity among diseases analogous to known relationships and serve as a reference to evaluate the performance of the regulatory similarity analysis.

3.3 Imputed DNAse hypersensitive sites and histone marks best capture genomic disease similarity

The regulatory similarities may be obtained by selecting different categories of regulatory datasets, e.g. histone modification marks, DNAse hypersensitive sites etc. (Supplementary Table S2). As each category answers different biological questions about the regulatory mechanisms involved, we tested each category separately. We compared regulatory similarities obtained with each category vs. those obtained using the shared genomic loci method. This approach was aimed at identifying categories of regulatory datasets that provide regulatory similarities best correlated with the shared genomic loci similarity used as a reference.

Among the ENCODE regulatory datasets, regulatory similarities based on the 161 regulatory datasets containing TFBSs were the most similar to the shared genomic loci similarities (Spearman’s r = 0.36, P-value = 4.80E-12). Regulatory similarities based on histone modification marks and DNAse hypersensitive site datasets correlated less with the shared genomic loci similarities (Spearman’s r = 0.29 and 0.16, respectively). Surprisingly, regulatory similarities based on chromatin states that encapsulate combinations of other regulatory marks (Ernst and Kellis, 2015) showed even less correlation with the shared genomic loci similarities (median Spearman’s r = 0.12). These results suggest selecting regulatory datasets is an essential step in measuring regulatory similarity among SNP sets, and highlights the importance of data-driven approach to analysis.

The Roadmap Epigenomics project provides experimentally and computationally obtained regulatory datasets (‘processed’/‘imputed’ datasets, respectively, Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, the regulatory regions were obtained using either ‘broad peak’, or ‘gapped peak’, or ‘narrow peak’ peak calling algorithms (Roadmap Epigenomics et al., 2015). We used each category of Roadmap Epigenomics datasets to identify regulatory datasets providing regulatory similarity best correlated with the shared genomic loci similarities.

The imputed regulatory data captured the relationships among the diseases better than the processed data (median Spearman’s r = 0.61 versus 0.48, respectively, Supplementary Table S4). Furthermore, regulatory similarities obtained using histone marks and DNAse hypersensitive sites defined by the ‘gapped peaks’ algorithm showed the best correlation with the shared genomic loci similarities (median Spearman’s r = 0.66 and 0.54, respectively, Supplementary Table S4). Notably, gapped peaks, which are broad domains that include at least one narrow peak, have been recommended for use by the Roadmap Epigenomics consortium (Roadmap Epigenomics et al., 2015), confirming our observations. Interestingly, using all regulatory data did not improve correlations of regulatory similarities with the shared genomic loci similarities (Spearman’s r = 0.55). These results indicate that computationally imputed regulatory datasets, in particular those with regulatory regions defined using the ‘gapped peak’ algorithm, perform best to measure regulatory similarity among the disease/trait-associated SNP sets.

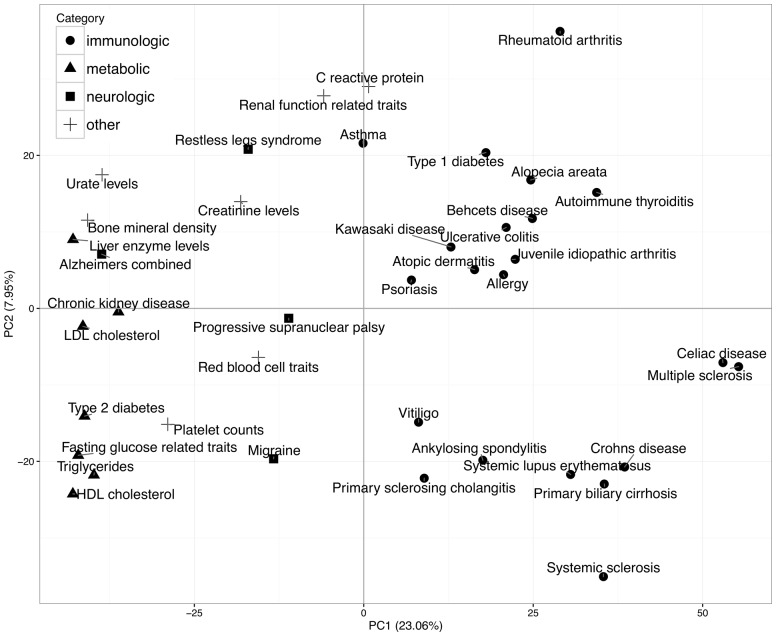

3.4 Autoimmune disease-associated SNP sets show distinct regulatory enrichments from other disease/trait-associated SNP sets

To compare regulatory similarities among the diseases represented by the corresponding SNP sets, we performed principal components analysis (PCA) of the disease-specific regulatory enrichment profiles. To obtain disease-specific regulatory enrichment profiles, we used imputed histone and DNAse ‘gapped peak’ regulatory data, although using combinations of other regulatory datasets yielded comparable results (data not shown). The PCA shows the immunologic diseases as the most regulatory distinct from the other diseases/traits (Fig. 2). Hierarchical clustering of the disease-specific regulatory enrichment profiles also grouped the immunologic disease-associated SNP sets as the most distinct from metabolic, neurologic and other diseases/traits (Supplementary Figure S3). We also visualized pairs of diseases with maximum regulatory similarity, and observed a similar grouping of immunologic diseases (Supplementary Table S6 and Supplementary Figure S4). This visualization highlighted known relationships among the diseases, e.g. ulcerative colitis and ankylosing spondylitis (Acheson, 1960), and strengthened disease similarities currently under question, e.g. multiple sclerosis and celiac disease (Mormile, 2015). These results demonstrate that SNP sets of the diseases with similar pathologies are enriched in similar regulatory datasets, potentially altering similar regulatory mechanisms.

Fig. 2.

Principal Component analysis of regulatory similarities among disease/trait-associated SNP sets. Shape-coding of the diseases/traits-specific categories highlights a group of immunologic diseases regulatory distinct from others

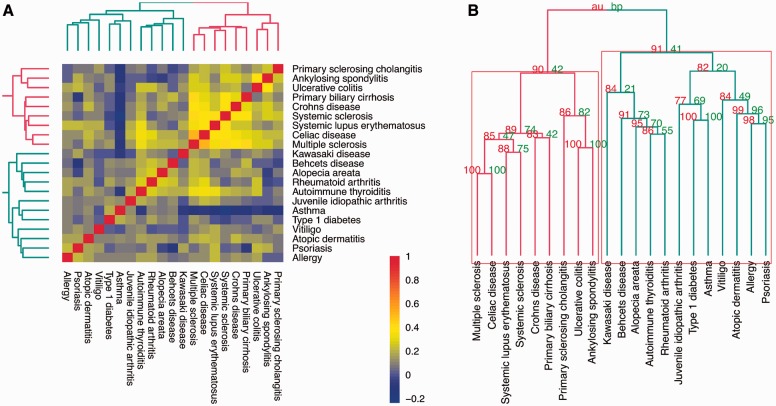

3.5 Two regulatory distinct groups of immunologic disease-associated SNP sets

We noted two subgroups of immunologic diseases formed distinct regulatory clusters (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Figure S3). Evaluating clustering stability of the regulatory enrichment profiles of 21 immunologic diseases with the pvclust R package (Suzuki and Shimodaira, 2006) identified two stable groups supported by the regulatory similarity data, each containing 12 and 9 diseases, respectively (α = 0.90, Fig. 3B). These clusters were stable irrespectively of combinations of the regulatory datasets used for regulatory enrichment analysis (data not shown). These results suggest that there are at least two groups of immunologic diseases with SNP sets enriched in distinct regulatory datasets.

Fig. 3.

Regulatory similarity among 21 immunologic diseases. (A) Correlogram of regulatory similarity among the diseases. Blue/yellow/red highlights negative/positive similarity between the disease-specific regulatory enrichment profiles, respectively, measured by Spearman correlation coefficients. Hierarchical clustering is performed using ‘ward’ metric. (B) Stability of the dendrogram of regulatory similarity among the diseases. ‘AU/P’, approximately unbiased/bootstrap probabilities, respectively (see pvclust R package; Suzuki and Shimodaira, 2006 for details). Red rectangles highlight two clusters of immunologic diseases supported by the data at α = 0.90 for AU probability. Red/green dendrograms further highlights the two clusters (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

3.6 T helper cell regulatory features are strongly enriched in a group of nine immunologic disease-associated SNP sets

Having defined the two groups of immunologic diseases, we focused on identifying regulatory differences between them. We compared regulatory enrichments between the two groups for statistically significant differences, i.e. identifying regulatory datasets significantly enriched in one but not the other group. Focusing on the regulatory data from 14 types of T cells and 9 types of B cells, we analyzed categories of histone modification marks, DNAse I hypersensitive sites and chromatin states. When using Roadmap Epigenomics data, we also investigated whether regulatory datasets defined using ‘broad-’, ‘narrow-’and ‘gapped’ peak calling algorithms will identify the same differential regulatory features. This analysis of individual categories of regulatory datasets simplifies interpretation of the observed regulatory differences.

Similar to Farh et al., we observed nearly all immunologic diseases-associated SNP sets showing some degree of enrichment in the regulatory datasets obtained from T helper cell subpopulations. However, our differential regulatory analysis placed nine immunologic diseases, ‘Multiple sclerosis’, ‘Celiac disease’, ‘Systemic lupus erythematosus’, ‘Systemic sclerosis’, ‘Crohns disease’, ‘Primary biliary cirrhosis’, ‘Ulcerative colitis’, ‘Ankylosing spondylitis’, ‘Primary sclerosing cholangitis’ as being significantly stronger enriched in the T helper cell-specific regulatory datasets (Supplementary Table S5). These results demonstrate how the regulatory similarity and differential regulatory analyses can refine our understanding of the SNP-regulatory associations. In summary, these observations position the aforementioned immunologic diseases, referred hereafter as ‘group 2’, as preferentially driven by the regulatory changes in T helper cell subpopulations, and suggest they may be best responsive to T helper cell targeting therapies.

3.7 H3K4me1, histone acetylation marks and DNAse I hypersensitive sites from T helper cells are enriched in nine immunologic disease-associated SNP sets

Using regulatory datasets defined with ‘broad-’, ‘narrow-’ and ‘gapped peak’ algorithms, we noted that the analysis with ‘broad peaks’ datasets identified more significant enrichment differences (e.g. 74 differential enrichments using processed ‘broad peak’ Histone marks data versus 67 ‘gapped peak versus 39 ‘narrow peak’ data). We also observed that the computationally imputed data provides more differential enrichments than the processed data (e.g. 428 imputed ‘gapped peak’ Histone marks versus 67 processed data). These observations corroborate our previous note that the computationally imputed regulatory marks are better suited for the regulatory enrichment analysis, and further suggest the use of imputed data defined using the ‘gapped peak’ algorithm. We describe enrichment results using the imputed ‘gapped peak’ regulatory data throughout the rest of the manuscript unless noted otherwise, and providing the results obtained with the other data types in the Supplementary Table S5.

In addition to the enhancer H3K4me1 mark, we observed the enrichment of several histone acetylation marks in the T helper cell subpopulations. H3K27ac, a mark associated with transcription initiation and open chromatin structure, was the most frequently enriched, followed by H4K12ac, H2BK120ac, H4K91ac (marks of transcription start sites), H3K14ac (critical for the recruitment of TFIID at the IFN-gamma locus) and other marks (Supplementary Table S5). Consistently, the ‘group 2’-associated SNP sets are enriched in DNAse hypersensitive sites in the primary T helper PMA-I stimulated cells (P-value = 1.62E-6 versus 9.32E-2 in the ‘group 1’ diseases) and other subpopulations of T helper cells. Taken together, these observations suggest that the ‘group 2’ diseases are associated with SNPs that may alter enhancers in the promoters of actively transcribed T helper cell-specific genes.

3.8 Enhancers in T helper cells subpopulations are enriched in the nine immunologic disease-associated SNP sets

To summarize combinatorial interactions of the regulatory marks into well-defined chromatin states, we used chromatin state data obtained using the ChromHMM learning system (Ernst and Kellis, 2012). Using data containing 15 chromatin states, we identified enhancers (‘7Enh’) as the most significantly enriched in the ‘group 2’-associated SNP sets. Enhancers from the primary T helper cells from peripheral blood were the most significantly enriched in the ‘group 2’ SNP sets (P-value = 2.72E-5 versus 1.35E-1 in the ‘group 1’ diseases, difference P-value = 5.20E-2). The ‘group 2’ SNP sets were also significantly enriched in enhancers of other T helper cell subpopulations, and depleted in quiescent regions (‘15Quies’, Supplementary Table S5). Analysis of 18 and 25 chromatin states identified similar enrichment differences and suggested involvement of enhancers in the Primary T CD8+ naïve and memory cells from peripheral blood (Supplementary Table S5). These results position the nine immunologic diseases from ‘group 2’ as likely to be driven by the regulatory changes in enhancers of T helper cells.

3.9 Cell type regulatory enrichment analysis identifies known cell specificity of the diseases

Numerous groups have reproducibly demonstrated that disease-associated variants are enriched within regulatory regions in phenotypically relevant cell types (Ernst et al., 2011; Gusev et al., 2014; Karczewski et al., 2013; Maurano et al., 2012; McVicker et al., 2013; Schaub et al., 2012; Thurman et al., 2012; Trynka et al., 2013; Ward and Kellis, 2012). Having established T helper cell subpopulations as potentially being affected in the nine immunologic diseases, we aimed to identify cell type specificity of all 39 disease/trait-associated SNP sets. The goal of the cell type regulatory enrichment analysis is to identify cell specificity of the regulatory datasets most frequently and most significantly associated with a SNP set. Under the hypothesis that disease-associated SNPs are disproportionally enriched in regulatory features in the cell types most relevant to the disease, GenomeRunner’s cell type regulatory enrichment analysis aims to identify these cell types.

As there’s no de facto standard definition of cell types specific for any of the diseases and traits analyzed in our study, we used common knowledge about disease pathology and compared our results with observations made by Farh et al. (2014). Similar to their observations, SNP sets associated with neurologic diseases were highly enriched in brain-specific regulatory datasets (Supplementary Table 7). Similarly, SNP sets associated with metabolic traits, such as ‘Fasting blood glucose’, ‘HDL/LDL cholesterol’, were the most frequently enriched in regulatory datasets from pancreatic islets, adipose tissue, liver. Notably, we observed ‘Fasting blood glucose’ and ‘Type 2 diabetes’ as being enriched in ‘Fetal heart’-specific regulatory datasets (P-values 3.24E-22 and 4.65E-28, respectively), confirming well-known link between diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (reviewed in Stolar and Chilton, (2003). Other trait-associated SNP sets also showed relevant cell type specificity of the regulatory enrichments, such as ‘creatine levels’ association with lung fibroblast primary cells (P-value 1.57E-21) and muscle cells, ‘bone mineral density’ association with chondrodyte cells (P-value 1.95E-22) and other similar observations (Supplementary Table S7). These results strengthen our observation that the disease-specific genomic changes are enriched in the regulatory datasets from relevant cell and tissue types.

Although we did not restrict cell type regulatory enrichment analysis to any particular cell type, we observed predominant association of T helper cell subpopulations and other immune cell types with the immunologic SNP sets. Similar to Farh, et al. (2014), we observed association of a few diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Kawasaki disease and primary biliary cirrhosis with B cell-specific regulatory datasets (Supplementary Table S7). We also observed significant enrichment of the ‘ulcerative colitis’ SNP set in the regulatory datasets from rectal mucosa, colon and intestine tissues (P-value = 5.23E-14), consistent with its bowel pathology. Other notable observations include ‘type 1 diabetes’ association with cells from placenta, adrenal gland, and pancreas (P-value = 5.28E-19). Concurrent with Farh et al. (2014) we ascertain that the cell type regulatory enrichment analysis allows a more focused insight into the cell type-specific effect of genetic variants upon regulatory context.

4 Discussion

The GenomeRunner web server is a significant improvement of our work on automating and simplifying the search for biologically interpretable relationships among high-throughput data (Dozmorov, 2015; Dozmorov et al., 2012, 2013, 2014; Sawalha and Dozmorov, 2015). Designed to be intuitive and fast, its downstream analyses enable interpretation of a wide range of biological problems, such as defining subgroups of patients by the regulatory similarity of the patient-specific SNP sets. We illustrate novel insights that can be obtained with GenomeRunner by analyzing 39 disease/trait associated SNP sets. Using regulatory datasets as a common reference, GenomeRunner was able not only detect known relationships among the diseases, but also identify a subgroup of immunologic diseases with SNPs strongly enriched in enhancers of T helper cell subpopulations. We further identified cell types relevant to disease pathology, with regulatory mechanisms likely to be altered by the corresponding SNPs.

To our knowledge, only three studies have investigated the use of similarity of patient-specific genomic information for classification purposes (Bakir-Gungor and Sezerman, 2011; Hofree et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). However, these studies use gene-centric reference to map SNPs to pathways and gene interaction networks, the idea we have also independently explored (https://github.com/mdozmorov/PathwayRunner). The regulatory similarity approach implemented in GenomeRunner is gene agnostic in that it uses regulatory datasets across the whole genome as a reference. This approach is expected to be especially useful in interpreting the functional impact of rare and non-coding genomic variants identified from whole genome sequencing.

Despite being a powerful tool for genomic data interpretation, GenomeRunner has some limitations. For example, its statistical model currently accommodates analysis of SNPs (point mutations) only. Although SNPs comprise ∼95% of genomic variants (Genomes Project et al., 2012), contribution of InDels (Ribeiro-Dos-Santos et al., 2015), Copy Number Variants (CNVs) (Curtis et al., 2012), structural variants (Kasowski et al., 2010) should also be considered as they are responsible for a much greater percentage of altered base pairs (Genomes Project, et al., 2012). Our future work includes accommodating genomic variants other than point mutations into the statistical framework of GenomeRunner.

The other feature of GenomeRunner is that SNPs are considered as independent. Our goal here was to keep the structure of GenomeRunner maximally simple, speed up statistical calculations, and put minimal requirements on the user-provided input files. Consequently, the interpretation-oriented analyses of GenomeRunner may be the final step in bioinformatics pipelines that preprocess the data, impute poorly genotyped regions and account for linkage disequilibrium (LD) depending on study prerequisites. If considering LD is crucial, we refer the user to the GoShifter enrichment tool (Trynka et al., 2015) that uses LD information from the Phase I 1000 genomes data release and estimates enrichments by local permutations. However, regulatory similarities among the 39 disease/trait-associated SNP sets obtained with GoShifter correlated less well with the shared genomic loci similarities (Supplementary Table S4). With the release of Phase III 1000 Genomes data (Genomes Project et al., 2015), we plan to include optional LD filtering for different populations.

The current version of GenomeRunner does not integrate other types of ‘omics’ information, such as mRNA and microRNA expression, and DNA methylation, shown to be well suited for the patient classification (Curtis et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). Our future application of GenomeRunner to the analysis of patient-specific mutation profiles includes integrating these layers of information and connecting the results with phenotype information. This integration will allow better understanding of the regulatory changes leading to disease manifestation.

In summary, we describe the GenomeRunner web server for identifying regulatory mechanisms potentially affected by the functional impact of SNP sets. Furthermore, we provide a means to compare different SNP sets by similarity of their regulatory enrichments. Used in connection with other tools, we hope the GenomeRunner web server will aid in understanding the epigenomic alterations associated with pathogenic genomic changes in complex genomics-driven diseases.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the Virginia Commonwealth University start-up fund (to M.G.D.), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (a subaward from P30 AR053483 to M.G.D.), an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (a subaward from P30 GM103510 to M.G.D.), and the National Science Foundation (ACI-1345426 to J.D.W.) for partial funding of this work. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Acheson E.D. (1960) An association between ulcerative colitis, regional enteritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Q. J. Med., 29, 489–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D. et al. (2012) BLUEPRINT to decode the epigenetic signature written in blood. Nat. Biotechnol., 30, 224–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmuller J. et al. (2001) Genomewide scans of complex human diseases: true linkage is hard to find. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 69, 936–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakir-Gungor B., Sezerman O.U. (2011) A new methodology to associate SNPs with human diseases according to their pathway related context. PLoS One, 6, e26277.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle A. et al. (2014) Characterizing the genetic basis of transcriptome diversity through RNA-sequencing of 922 individuals. Genome Res., 24, 14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein B.E. et al. (2010) The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat. Biotechnol., 28, 1045–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer W., Bonilla C. (2008) Common and rare variants in multifactorial susceptibility to common diseases. Nat. Genet., 40, 695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carninci P. et al. (2005) The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science, 309, 1559–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung V.G., Spielman R.S. (2009) Genetics of human gene expression: mapping DNA variants that influence gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet., 10, 595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradin O. et al. (2014) Combinatorial effects of multiple enhancer variants in linkage disequilibrium dictate levels of gene expression to confer susceptibility to common traits. Genome Res., 24, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis C. et al. (2012) The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature, 486, 346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale R.K. et al. (2011) Pybedtools: a flexible Python library for manipulating genomic datasets and annotations. Bioinformatics, 27, 3423–3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner J.F. et al. (2012) DNase I sensitivity QTLs are a major determinant of human expression variation. Nature, 482, 390–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozmorov M.G. (2015) Polycomb repressive complex 2 epigenomic signature defines age-associated hypermethylation and gene expression changes. Epigenetics, 10, 484–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozmorov M.G. et al. (2012) GenomeRunner: Automating genome exploration. Bioinformatics, 28, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozmorov M.G. et al. (2013) Systematic classification of non-coding RNAs by epigenomic similarity. BMC Bioinformatics, In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozmorov M.G. et al. (2014) Epigenomic elements enriched in the promoters of autoimmunity susceptibility genes. Epigenetics, 9, 276–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren H. et al. (2003) Mutation rate variation in the mammalian genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Develop., 13, 562–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENCODE Project Consortium. (2004) The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project. Science, 306, 636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J., Kellis M. (2012) ChromHMM: automating chromatin-state discovery and characterization. Nat. Methods, 9, 215–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J., Kellis M. (2015) Large-scale imputation of epigenomic datasets for systematic annotation of diverse human tissues. Nat Biotechnol, 33, 364–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J. et al. (2011) Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature, 473, 43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farh K.K. et al. (2014) Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature, 518, 337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili T. (2015) dendextend: an R package for visualizing, adjusting and comparing trees of hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics, 31, 3718–3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genomes Project, C. et al. (2012) An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature, 491, 56–65. [TQ2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genomes Project,C. et al. (2015) A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature, 526, 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz J. et al. (2011) Analysis of DNA methylation in a three-generation family reveals widespread genetic influence on epigenetic regulation. PLoS Genet., 7, e1002228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusev A. et al. (2014) Partitioning heritability of regulatory and cell-type-specific variants across 11 common diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 95, 535–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraksingh R.R., Snyder M.P. (2013) Impacts of variation in the human genome on gene regulation. J. Mol. Biol., 425, 3970–3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindorff L.A. et al. (2009) Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 9362–9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofree M. et al. (2013) Network-based stratification of tumor mutations. Nat. Methods, 10, 1108–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski K.J. et al. (2013) Systematic functional regulatory assessment of disease-associated variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 9607–9612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasowski M. et al. (2010) Variation in transcription factor binding among humans. Science, 328, 232–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasowski M. et al. (2013) Extensive variation in chromatin states across humans. Science, 342, 750–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpinen H. et al. (2013) Coordinated effects of sequence variation on DNA binding, chromatin structure, and transcription. Science, 342, 744–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R.M. et al. (2013) The UCSC genome browser and associated tools. Brief. Bioinformatics, 14, 144–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (2011) Tabix: fast retrieval of sequence features from generic TAB-delimited files. Bioinformatics, 27, 718–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. et al. (2011) DOSim: an R package for similarity between diseases based on Disease Ontology. BMC Bioinformatics, 12, 266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. et al. (2011) Cistrome: an integrative platform for transcriptional regulation studies. Genome Biol., 12, R83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurano M.T. et al. (2015) Large-scale identification of sequence variants influencing human transcription factor occupancy in vivo. Nat. Genet., 47, 1393–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurano M.T. et al. (2012) Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science, 337, 1190–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniell R. et al. (2010) Heritable individual-specific and allele-specific chromatin signatures in humans. Science, 328, 235–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVicker G. et al. (2013) Identification of genetic variants that affect histone modifications in human cells. Science, 342, 747–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley M. et al. (2004) Genetic analysis of genome-wide variation in human gene expression. Nature, 430, 743–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormile R. (2015) Multiple sclerosis and susceptibility to celiac disease: an osteopontin gene haplotypes affair? Immunol. Lett., 163, 132–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca R. et al. (2015) dSysMap: exploring the edgetic role of disease mutations. Nat. Methods, 12, 167–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M.R. et al. (2012) An abundance of rare functional variants in 202 drug target genes sequenced in 14,002 people. Science, 337, 100–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neph S. et al. (2012) BEDOPS: high-performance genomic feature operations. Bioinformatics, 28, 1919–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipson B., Smyth G.K. (2010) Permutation P-values should never be zero: calculating exact P-values when permutations are randomly drawn. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol., 9, Article39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A.R., Hall I.M. (2010) BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics, 26, 841–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy T.E. et al. (2012) Effects of sequence variation on differential allelic transcription factor occupancy and gene expression. Genome Res, 22, 860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-Dos-Santos A.M. et al. (2015) Populational landscape of INDELs affecting transcription factor-binding sites in humans. BMC Genomics, 16, 536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roadmap Epigenomics,C. et al. (2015) Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature, 518, 317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom K.R. et al. (2013) ENCODE data in the UCSC Genome Browser: year 5 update. Nucleic Acids Res., 41, D56–D63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawalha A.H., Dozmorov M.G. (2015) Epigenomic functional characterization of genetic susceptibility variants in systemic vasculitis. J. Autoimmun., 67, 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub M.A. et al. (2012) Linking disease associations with regulatory information in the human genome. Genome Res., 22, 1748–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolar M.W., Chilton R.J. (2003) Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular risk, and the link to insulin resistance. Clin. Ther., 25(Suppl B), B4–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranger B.E. et al. (2007) Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat. Genet., 39, 1217–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki R., Shimodaira H. (2006) Pvclust: an R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics, 22, 1540–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team, R.D.C. ( 2013) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Thurman R.E. et al. (2012) The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature, 489, 75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F. et al. (2014) Functional characterization of breast cancer using pathway profiles. BMC Med. Genomics, 7, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trynka G. et al. (2013) Chromatin marks identify critical cell types for fine mapping complex trait variants. Nat. Genet., 45, 124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trynka G. et al. (2015) Disentangling the effects of colocalizing genomic annotations to functionally prioritize non-coding variants within complex-trait loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 97, 139–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B. et al. (2014) Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nat. Methods, 11, 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward L.D., Kellis M. (2012) Evidence of abundant purifying selection in humans for recently acquired regulatory functions. Science, 337, 1675–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren J.D. et al. (2004) Knowledge discovery by automated identification and ranking of implicit relationships. Bioinformatics, 20, 389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.