Abstract

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also known as stress cardiomyopathy, is a syndrome that affects predominantly postmenopausal women. Despite multiple described mechanisms, intense, neuroadrenergic myocardial stimulation appears to be the main trigger. Hyperthyroidism, but rarely hypothyroidism, has been described in association with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Herein, we present a case of stress cardiomyopathy in the setting of symptomatic hypothyroidism.

Key words: Elderly, hypothyroidism, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

INTRODUCTION

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM), also known as stress cardiomyopathy, is a complex entity that can mimic an acute coronary syndrome, particularly when chest pain is present. A common pathophysiologic mechanism involving intense neuroadrenergic myocardial stimulation has been postulated, but the list of its potential causes has increased significantly over the past two decades. Profound hypothyroidism can have a variety of well-described cardiovascular manifestations, including diastolic hypertension, bradycardia, and decreased contractility; herein, we present an unusual acute cardiovascular manifestation of severe hypothyroidism: TCM.

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old female with a history of hypertension, smoking, and gastroesophageal reflux disease came to the emergency department for evaluation of progressive fatigue, weakness, and lightheadedness over the course of weeks. She also reported intermittent, atypical episodes of sharp chest pain, unrelated to exertion, lasting <5 min at a time. On initial assessment, her blood pressure was 146/102 mmHg, with a heart rate of 80 beats/min and regular. Her physical examination was significant for obesity, dry skin, and trace edema of her lower extremities. Her complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and D-dimer were within normal limits. Her initial troponin was <0.01 ng/dL. Her chest X-ray did not reveal any acute abnormality. Initial electrocardiographic (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm with no ischemic signs.

During her evaluation in the Emergency Department where she had an episode of severe chest pain associated with palpitations and lightheadedness. A 30 second run of accelerated junctional rhythm at a rate of 87 beats/min was documented at the time. Troponin levels at 3 h peaked at 0.42 ng/dL and declined to 0.35 ng/dL at 6 h. Repeat ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with new T-wave inversions in anterolateral leads. At that point, the patient was medically managed as a non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Additional laboratory data included a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) of 77 mIU/L with suppressed peripheral thyroid hormones as well a total cholesterol level of 348 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein of 75 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein of 248 mg/dL with triglycerides of 122 mg/dL. Twelve hours later, the patient underwent a left heart catheterization, which showed no evidence of obstructive coronary artery disease [Figure 1]; ventriculogram revealed a mildy depressed ejection fraction, with basal hypercontractility and apical akinesis, consistent with TCM [Figure 2]. She was started on oral levothyroxine, metoprolol, aspirin, and atorvastatin. She was discharged on the day 4 with no recurrence of symptoms.

Figure 1.

Coronary angiogram shows no evidence of significantly obstructive disease in the right (a) and left (b) coronaries

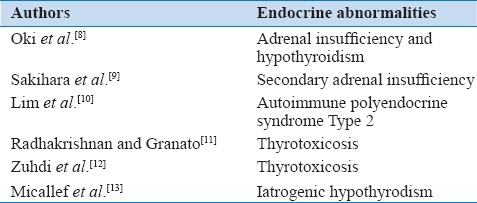

Figure 2.

Ventriculogram during diastole (left) and systole (right), with classic apical ballooning and preserved basal contractility

DISCUSSION

Diagnostic criteria for TCM have been well established,[1] and include the acute onset of transient left ventricular dysfunction following an inciting trigger, variable clinical, and ECG manifestations of myocardial ischemia (including ST segment depression or elevation and/or T-wave inversions), discrete elevation of cardiac enzymes, apical systolic ballooning with preserved or increased contractility at the base, and no evidence of obstructive coronary artery disease on angiography.

As seen in this case, the specific diagnosis is usually made retrospectively, after workup and therapies have been directed toward a suspected acute coronary syndrome. Late prognosis is usually good, but clinicians must be aware of acute complications such as cardiogenic shock, pulmonary edema, and torsade de pointes.[2] Recurrence rates are not negligible and could be higher than 10% when patients are followed prospectively.[3]

There has not been a single unifying mechanism to reconcile the presence of severe segmental ventricular dysfunction, independent of the territory of a single coronary artery, with abnormal metabolism in TCM, and thus, the pathophysiology is likely multifactorial.

The cardinal trigger appears to be excessive, neurogenic sympathetic stimulation during stress, either physical or emotional. These results in neurogenic myocardial stunning with abnormal glucose and fatty acid metabolism, mediated by catecholamine-induced enzymatic and surface receptor changes. This theory is supported by multiple animal models,[4] and indirectly suggested by the significantly impaired uptake of123 I- metaiodobenzylguanidine (a radionuclide analog of norepinephrine) in a distribution that matches the mechanically affected segments.[5]

In addition, neuroadrenergic stimulation of the epicardial or arteriolar coronary arteries can result in transient but intense coronary vasospasm and endothelial dysfunction, which can further impair metabolism and function.[6] In contrast with patients who sustain an acute coronary syndrome such as an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, transient microvascular dysfunction has been demonstrated in patients with TCM, with the use of adenosine and myocardial contrast echocardiography.[7]

Hormonal dysfunction has been implicated in the etiology of multiple cases of TCM [Table 1]. In contrast to several reports related to increased thyroid function, there has only been one description of TCM in association with radioactive iodine-induced hypothyroidism.[13] To best of our knowledge, this is the first description of stress cardiomyopathy in the setting of spontaneous, isolated primary hypothyroidism.

Table 1.

Endocrine abnormalities implicated in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

The relationship between abnormal coronary circulation and hypothyroidism has been the subject of investigation. The Rotterdam study, a large epidemiological cohort from The Netherlands,[14] found that subclinical hypothyroidism is independently associated with a greater prevalence of aortic atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction in elderly women. Coronary flow reserve, which represents the ability of the coronary circulation to dilate in response to increased metabolic demands, has been found to be significantly impaired in both subclinical and overt hypothyroid patients, independently of abnormal lipid parameters.[15] The degree of microvascular dysfunction seems to be inversely proportional to the levels of TSH; consistent improvement of impaired coronary flow reserve has been demonstrated after levothyroxine replacement therapy.[16] Animal models have shown dramatic reductions in myocardial arterioles in hypothyroid rats,[17] leading to impairment of both resting and adenosine-induced maximum blood flow.

The most appealing hypothesis is a significant reduction in endothelial nitric oxide synthase, which could not only lead to arteriolar rarefaction but also predispose to vasospasm and abnormal vasodilatation. Coronary vasospasm has been previously described in patients with hypothyroidism.[18] Furthermore, thyroid hormones are known to down-regulate the expression of myocardial alpha 1-adrenergic receptors, and hormone deprivation could be related with increased expression of these,[19] predisposing to myocardial stunning in the setting of intense adrenergic stimulation.

CONCLUSIONS

The list of potential causes of TCM continues to grow, and severe hypothyroidism should be included as well. Coronary microcirculatory dysfunction and abnormal myocardial expression of adrenergic receptors have been demonstrated in hypothyroidism, and this hormonal preconditioning might serve as a substrate for neuroadrenergic myocardial stunning. This association merits further investigation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. Todd Miller for his kind suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, Lerman A, Barsness GW, Wright RS, et al. Systematic review: Transient left ventricular apical ballooning: A syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:858–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelini P. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning: A unifying pathophysiologic theory at the edge of Prinzmetal angina. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;71:342–52. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elesber AA, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Wright RS, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Four-year recurrence rate and prognosis of the apical ballooning syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:448–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorfman TA, Iskandrian AE. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: State-of-the-art review. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009;16:122–34. doi: 10.1007/s12350-008-9015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cimarelli S, Sauer F, Morel O, Ohlmann P, Constantinesco A, Imperiale A. Transient left ventricular dysfunction syndrome: Patho-physiological bases through nuclear medicine imaging. Int J Cardiol. 2010;144:212–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angelini P. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: What is behind the octopus trap? Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37:85–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galiuto L, De Caterina AR, Porfidia A, Paraggio L, Barchetta S, Locorotondo G, et al. Reversible coronary microvascular dysfunction: A common pathogenetic mechanism in apical ballooning or Tako-Tsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1319–27. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oki K, Matsuura W, Koide J, Saito Y, Ono Y, Yanagihara K, et al. Ampulla cardiomyopathy associated with adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:391–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakihara S, Kageyama K, Nigawara T, Kidani Y, Suda T. Ampulla (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy caused by secondary adrenal insufficiency in ACTH isolated deficiency. Endocr J. 2007;54:631–6. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k07-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim T, Murakami H, Hayashi K, Watanabe H, Sasaki H, Muto H, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome II. J Cardiol. 2009;53:306–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radhakrishnan A, Granato JE. An association between Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and thyroid storm. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:126–30. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.05.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuhdi AS, Yaakob ZH, Sadiq MA, Ismail MD, Undok AW, Ahmad WA. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in association with hyperthyroidism. Medicina (Kaunas) 2011;47:219–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Micallef T, Gruppetta M, Cassar A, Fava S. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and severe hypothyroidism. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2011;12:824–7. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283403454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hak AE, Pols HA, Visser TJ, Drexhage HA, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Subclinical hypothyroidism is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction in elderly women: The Rotterdam study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:270–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-4-200002150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baycan S, Erdogan D, Caliskan M, Pamuk BO, Ciftci O, Gullu H, et al. Coronary flow reserve is impaired in subclinical hypothyroidism. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30:562–6. doi: 10.1002/clc.20132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oflaz H, Kurt R, Sen F, Onur I, Cimen AO, Elitok A, et al. Coronary flow reserve after L-thyroxine therapy in Hashimoto's thyroiditis patients with subclinical and overt hypothyroidism. Endocrine. 2007;32:264–70. doi: 10.1007/s12020-008-9037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang YD, Kuzman JA, Said S, Anderson BE, Wang X, Gerdes AM. Low thyroid function leads to cardiac atrophy with chamber dilatation, impaired myocardial blood flow, loss of arterioles, and severe systolic dysfunction. Circulation. 2005;112:3122–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.572883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawson WE, Sodums MT, Lense L, Cohn PF. Coronary artery spasm in hypothyroidism. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:223–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metz LD, Seidler FJ, McCook EC, Slotkin TA. Cardiac alpha-adrenergic receptor expression is regulated by thyroid hormone during a critical developmental period. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:1033–44. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]