Abstract

The pharmaceutical legal framework is a very important infrastructure in achieving predefined goals in pharmaceutical sector: Accessibility, quality, and rational use of medicine. This study aims to review the current pharmaceutical sector-related legal provisions in Iran where the Food and Drug Organization (FDO) is in charge of regulating all issues related to the pharmaceutical sector. The main laws and regulations enacted by parliament and cabinet and even internal regulations enacted by the Ministry of Health or Iran FDO are reviewed. Different laws and regulations are categorized according to the main goals of Iran national drug policy.

Keywords: Accessibility, availability, counterfeit medicines, pharmaceutical trade-related aspects, rational use of medicine

INTRODUCTION

It is the basic responsibility of the governments to ensure that drugs to be used by the public meet the established standards of quality, safety, and efficacy. Moreover, importing, manufacturing, sales, and distribution of drugs must be investigated, supervised, and regulated by regulatory organizations. As a general principle, the aim of all pharmaceutical laws should be to protect patients. Hence, pharmaceutical system, in contrast with most of other business sectors, has always been exposed to more governmental interferences. These interventions and supervisions have been often justified by the economic theories of market failure in health care and the critical role of medicines in public health.[1,2,3] An independent and expert-based authority to control issues around the pharmaceutical market has also been considered logical due to the particular characteristics of the health-care market that make it distinct from other markets.

The multidimensional structure of the pharmaceutical system and need for a common framework for dealing with existing problems have led to the development of national pharmaceutical policies; moreover, legal frameworks are used to achieve national pharmaceutical policy goals. Although the national policies can be developed and implemented differently among different countries, they have some common goals including “accessibility”, “rational use”, and “quality” of medicines which will be discussed further.[4] To approach political targets, Iran's pharmaceutical market, with a history of around 60 years of domestic production,[5] has evolved in various old and new laws context.

Pharmaceutical legislation system has been developed to ensure the achievement of health and pharmaceutical policies. Governments should pay attention to regular assessment of different parts of the system. Currently, pharmaceutical system in Iran is suffering from many dysfunctions including insufficient industry development, unaffordability of medicines, especially for chronic and life-threatening diseases, controversies around the quality of domestically produced generic medicines, regular shortages of some medicines in the market, unregulated market of medicinal herbs, irrational prescribing by physicians, self-medication by patients, selling medicines by pharmacies without prescription, counterfeit medicines, proliferation of unethical competition between distribution companies, and inefficient structure of current supply chain. The existing challenges in the pharmaceutical system make it necessary to conduct several studies to evaluate strengths and weaknesses of pharmaceutical law and also enforcement system in Iran to solve the potential problems. According to this review and a few other studies around legal aspects of the pharmaceutical system in Iran, several problems could be mentioned including lack of sufficient legislation about conflict of interest,[6] inadequate punishment for counterfeit medicines in relevant laws,[7] and pharmaceutical ethics.[8]

PHARMACEUTICAL LAW SOURCES IN IRAN (LEGAL SYSTEM)

Pharmaceutical legal framework (pharmaceutical legislative system)

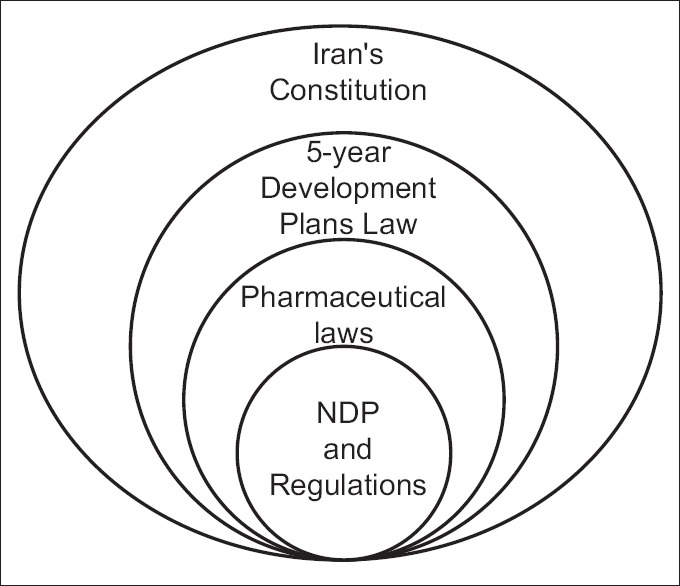

Pharmaceutical legal framework in Iran can be categorized into five discrete types (levels):

Type-1: It expresses the major goals and insights. At this level, there is a constitution that is the base for all other legal decisions in different parts of legislation system

Type-2: Long- and middle-term plans and laws which are approved and declared by the parliament or Iran's Supreme Leader to be presumed as a base for shorter plans

Type-3: The pharmaceuticals laws approved by the parliament

Type-4: The regulations (acts and bylaws) approved by the cabinet (government)

Type-5: International regulations and agreements [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The structure of pharmaceutical legislative system in Iran

Health in constitution

In the Islamic Republic of Iran's constitution, as the most superior law, public health issues, and supports for patients are highly accentuated. In the 12th clause of Article 3 of the constitution, the government is obligated to establish a fair and authentic economic environment with reference to the Islamic rules and apply all its capacities to provide social welfare, remove poverty, and deprivation in the terms of nutrition, housing, labor, public health, and to implement universal coverage of health insurance. Moreover, in Article 29 of the constitution, the provision of social security by health-care services has been considered as one of its components. In addition, the 1st clause of Article 43 discusses the fulfillment of vital needs of people including public health as well as housing, feeding, clothing, and education.

Considering the complexity of pharmaceutical issues, sharing the experiences between countries could help to overcome the potential weaknesses. In this study, we aimed to overview Iran's legal pharmaceutical framework and its major topics regarding the National Development Plan goals to provide a broad image of legal infrastructures in the Iranian pharmaceutical market.

ACCESSIBILITY-RELATED REGULATION

Availability of pharmaceuticals

According to the law of medical, pharmaceutical, edibles and potables (1995), and subsequent amendments, which is among the oldest integrated laws related to medicines in Iran, importing, exporting, selling, and purchasing medicines without acquiring a license from the Ministry of Health (MOH) is considered as a crime (3rd clause). Furthermore, the fourth chapter of this law discusses the requirements for manufacturing and importing biological and laboratory products. In Article 14, it is specified that a permit from MOH is required for the following: Importing any form of biological products such as serum, vaccine, pediatric nutrition, or medicines from foreign countries either by private or public sector; medicine clearance; manufacturing any type of medicines or biological products; and medicine supply and sell or export. Moreover, according to Article 20 of this law, to import and/or produce any type of medicines and biological products, qualification assessment is authorized to “Recognition Committee” which consists of the following:

A pharmacologist

Two faculty members from pharmacy schools

Either a pharmacist from pharmaceutical industry or an expert in biology or an herbal expert familiar with the subject

One faculty member from medicine schools

Director of control laboratories of the MOH

Director of pharmaceutical regulatory affairs of the Food and Drug Organization (FDO).

Based on this law, all pharmaceutical products must be registered in national drug list (NDL) to be authorized for the market. However, the legislator has allowed some products out of the NDL to be limitedly available for some patients in critical situations. According to the Act of Emergency Pharmaceutical Centers (EPCs) (2008), the pharmaceutical products that are not registered in the NDL could be imported by institutions called EPCs, whenever a shortage or crisis happens or available alternatives are not supposed by a physician to be sufficient for a specific patient.

According to Article 1 of this Act, these medicines must be only procured from the qualified international wholesalers approved by the FDO; moreover, only the generic forms of the medicines manufactured in the UK, France, Germany, Sweden, Canada, the USA, and Switzerland are allowed to be imported.

As these products are not registered in the NDL and their profiles of efficacy, safety, and quality have not been assessed by the FDO, physician and patients have to consent undertaking the responsibility of probable side effects or lack of efficacy, based on Article 2. Moreover, according to this Act, any marketing, advertisement, and promotional activities about these products are prohibited.

The EPCs are obliged to keep at least 1% of each batch series of imported products as a sample to be assessed in case of any problem. In addition, these centers are directly and stealthy controlled by the FDO through both regular and random inspections.

Geographic accessibility

Geographic accessibility to pharmacies in different parts of the country (as a factor of accessibility to medicines) has been mentioned in Pharmacy Act (2006). Article 11 of this Act discusses the number of pharmacies to be established. Based on this article, for areas with up to 300,000 urban or rural populations, with at least one active physician's office or public clinic, one pharmacy is permitted for every 7000 population, and for areas with more than 300,000 population, one pharmacy is allowed for every 6000 population. Moreover, according to the 12th Article of this Act, one 24 h active pharmacy can be established for every 65,000 urban or rural populations. Due to several issues such as fair geographical access to pharmacies in different cities, a minimum distance between pharmacies is considered in this Act. According to the 18th Article, the distance between daily pharmacies and 24 h active pharmacies can be summarized as below:

Fifty meters in cities with up to 250,000 population

Seventy-five meters in cities with up to 500,000 population

One hundred and fifty meters in cities with up to 1,000,000 population

Three hundred meters in cities with more population.

In addition, based on the law of pharmaceutical supply in deprived regions and to ensure accessibility to medical services in these areas, if there are no volunteers from private or cooperative sectors for investing to establish pharmacies, the MOH is obligated to provide such services through its own health-care units.

Although the geographic accessibility to pharmacy is a vital factor in population's accessibility to medicines, it would not be sufficient criteria without a functioning distribution system. In order to organize drug distribution companies all around the country, Pharmaceutical Distribution Act (2006) was approved by the cabinet. By definition, new product development cares those which distribute pharmaceuticals across the country. The National Pharmaceutical Distribution Companies should establish their own branches in at least one-third of the provinces (31 provinces in 2014) and contract with provincial distribution companies in states. According to this Act, distribution companies must also employ a responsible pharmacist and introduce him/her to the FDO.

Affordability of pharmaceuticals

The affordability of medicine for all people has been considered by both health insurance mechanisms and pharmaceutical pricing regulations.

Health insurance

The universal health coverage has been emphasized in the universal health insurance law (1994) to cover all population against health-care expenditures. The health insurance system in Iran has a very fragmented structure. There are dozens of public health insurance organizations as well as many private ones covering small proportions of population. Before 2004, the main policies of these organizations and funds had been determined by the MOH and via a supreme council of health insurance, but after enacting the law of welfare and social security (2004), the responsibility and the council were transferred to the Ministry of Welfare and Social Security.

The reform in health insurance structure has also been mentioned in mid-term plan laws. In the 38th Article of the law of the fifth 5-year development plan (2010), the integration of several health insurances has been discussed, and the government is bound to provide the obligatory and general health insurance mechanisms. According to this law, the current fragmented structure of health insurance is planned to become integrated into a new organization called “Iranian health insurance organization.” The 5-year development plans are the codified programs drafted by the government and presented to the national parliament every 5 years. In case of authorization, it would be accounted for the macro plans with a mid-term vision to be considered by the government in annual programming, budgeting, and some other special decision-makings.

Pricing regulation

In June 2011, the new Pharmaceutical Pricing Act was introduced by the FDO, which addresses some general goals including quality assurance, safety, efficiency improvement, and assured accessibility. Prior to this time, the pricing strategy for medicines was based on a “cost-plus” approach.

According to the new regulation, the price of original medicines in their patent protection period would be calculated by considering their prices in either exporter or reference countries; moreover, the price of a particular medicine in Iran's market must be lower than its price in all those countries. The price setting for patent-expired original medicines would be calculated based on either reference countries’ prices or at least via calculating 20% reduction from their under patent prices, whichever is lower.

The price of domestic or imported generic medicines would be calculated either at least 60% lower than the least price of original product in reference countries (for orphan medicines, it would be 40% lower) or by considering the lowest price of that generic medicine (by the same producer) in reference countries, whichever is lower. The reference countries in this Act are Greece, Turkey, Spain, Saudi Arabia, and Aljazeera.

It is worth mentioning that the “cost-plus” method is still used only for the generic medicines without any trade mark or brand name.

Other strategies

In addition to these two strategies, the government is about to use other measures to make pharmaceutical and other health services more affordable. According to the law of the fifth 5-year development plan (2010), Article 34, in order to achieve health equity, reduce out of pocket expenditure to a maximum of 30% of total health expenses, provide fair public access to health-care services, and provide financial aids to cover the catastrophic costs, the government is bound to add up to 10% of the net total income resulting from the law of subsidiary targeting, to the health sector budget.

QUALITY-RELATED REGULATION

The Act of production and importation of pharmaceuticals and subsequent amendments (1989) provide one set of regulations to assure the quality of pharmaceutical products in the market. According to Article 12 of this Act, the establishment of a pharmaceutical manufacturing company must be licensed by both the ministry of industry and the MOH. Moreover, all pharmaceutical companies are obligated to introduce a responsible officer (qualified pharmacist with an experience in the industry). The importation of products also must be under the authorization of MOH.

According to this Act, the first batch of each new pharmaceutical or biological product (domestically manufactured or imported) must be analyzed in MOH laboratories; they can be distributed in the market only after being approved. Furthermore, the marketed products should be randomly sampled regularly and sent to the laboratories for postmarketing quality evaluation. According to this Act, the importation of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (APIs) by domestic manufacturers must be also under the supervision and approval of the MOH.

Regarding the regulation of the responsibilities of responsible officer in pharmaceutical industry (1996), the responsible officer in a pharmaceutical company has some responsibilities monitored by the MOH including:

Supervising the preparation of data about all products for each product series including quality control process

Assessing and approving all processes related to the acquisition of a production license for a new product

Communicating regularly with the MOH about formulations and packaging of products and preparing two reports annually about the good manufacturing practices status of the company for the FDO

Considering all the MOH regulations about formulation and packaging and informing the MOH about any changes in the API, formulation, packaging, and production process.

In addition, the Iranian pharmaceutical legislative system presents all issues around contract manufacturing and under license manufacturing of pharmaceutical products.

Counterfeit medicines

The counterfeit medicines have also been mentioned in the law of medical, pharmaceutical, edibles and potables (1955), and subsequent amendments. In Article 18 of this law discusses the punishments for importing, producing, and dispensing counterfeit medicines. It should be mentioned that in Iran, counterfeit medicine is defined as any pharmaceutical product without passing the FDO regulatory process regardless of their common problems associated with their active ingredients or impurities.

REGULATIONS ON RATIONAL USE OF MEDICINE

Monitoring rational prescription

Following the Prescription Survey Committee Act (1996), several committees have been established in each province with the aim of improving the quality of medical services, reducing the irrational drug use, and facilitating medical and pharmaceutical planning. Each committee monitors the prescriptions and uses audit measures to improve prescription patterns of physicians. In case of negligence and repeating the faults, transgressions will be reported to legal institutions. These committees are under the supervision of a Central Committee in the FDO.

Regulations of marketing and promotional practices

According to the 5th clause of the law of medical, pharmaceutical, edibles and potables (1955) and subsequent amendments, medical and pharmaceutical institutions, practitioners, and other institutions are not permitted to announce deceptive advertisements or those which are considered to be against technical rights, medical dignities, or public chastity by the MOH.

In addition, by the Act of Marketing and Advertisement for pharmaceuticals and biologics (2007), Iran's MOH tries to organize marketing and promotional activities of domestic and multinational companies in Iran's pharmaceutical market. This regulation has been enforced for all other classes of pharmaceuticals and biologics; however, the herbal and natural medicines are exempted.

Regarding Article 5 of this Act, introducing medicines is only permitted in scientific medical journals and websites. Moreover, introducing medicines to medical professionals is permitted via providing free samples, brochures, catalogs, giving a speech in scientific seminars, E-mails, and also detailing.

In Article 6 of this Act, the pharmaceutical institutions are allowed to employ medical representatives for introducing their products to medical professionals. These institutions are responsible for all professional activities of their medical representatives. This regulation states the bonus and incentives during the practices of presentation must be set in a way that does not motivate the target groups to violate professional principles. The medical representatives also are obliged to behave in accordance with legal, religious, scientific, and professional principles while introducing the products. However, this part of Article 6 does not seem to be sufficiently clarified and controllable.

Article 8 of this regulation discusses the pharmaceutical firms’ bonuses to physicians. The characteristics of bonuses are somehow stated by the regulator:

Bonuses have to be related to treatments and could be used in favor of patients

Bonuses must have signs of that medicine or firm

Their values must not be extraordinary from a social point of view and should not motivate physicians to prescribe it irrationally

Moreover, all pharmaceutical bonuses have to be declared by the companies to the MOH every 3 months.

Article 9 of this Act focuses on the payments by pharmaceutical firms for health-care professionals who travel within or out of the country. By this article, this type of payment is allowed under some legal consideration and only for the promotion of scientific level (for example traveling to a scientific course or seminar). The invitation to professionals has to be sent from scientific institutions or medical universities; furthermore, this Act does not allow payment for their families and other companions.

PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES REGULATION

Pharmacy practice

Pharmacies are health-care centers that dispense medicines and provide pharmaceutical services to people. According to the law of medical, pharmaceutical, edibles and potables (1955) and subsequent amendments, the establishment of pharmacies as well as all other medical institutions must be authorized only by the MOH via obtaining necessary certificates. Upon this law's 2nd clause, technical affairs of the pharmacy should only be supervised by a responsible officer (a licensed pharmacist) recognized by the MOH.

The separation of prescription from dispensing is addressed in the first section of this article. It has been mentioned that pharmacists cannot interfere specialized medical affairs, except for the primary cares before the arrival of a physician. In addition, although Article 5 of this law says that manipulation of medical prescriptions by a pharmacist, without physician's consent is prohibited, in the third-waver, generic substitution is exempted. (It is legal in Iran.)

In 2006, the most comprehensive regulation for pharmacies was enacted by the cabinet as Pharmacy Act, illustrating the general issues related to retail pharmacies. According to Article 2 of this Act, a retail pharmacy is considered as a medical institute which is active officially to provide pharmaceuticals, dietary supplements, infant nutrition, medical equipment, cosmetics, and sanitary products. To establish a pharmacy, a valid license from a legitimate committee of the MOH is needed, and a qualified pharmacist should be nominated as the technical officer. Upon Article 4 of this Act, each qualified pharmacist is only permitted to receive one pharmacy license.

According to this Act's third article, obligated working time of daily pharmacies is 12 h between 8 a.m. and 10 p.m.

Upon the 25th Article of this Act, the duties of responsible pharmacist can be listed as below:

Active presence in the pharmacy during defined hours

Checking the prescription upon regulations

Providing over-the-counter drugs according to their list and regulations

Conducting the practice of repacking based on regulations and providing medicines with necessary explanation to customers

Checking the probable ambiguities and errors, and substitution of prescribed medicines after consulting with the physician, if needed

Supervising the storage conditions, appearance, physical quality, and expiration date of medicines

Preparing and offering galenical and compounding medicines in a way that does not prevent him/her from other its own duties as a responsible pharmacist

Filling out questionnaires and sending them back to research centers

Declaring medication's errors according to standard models

Reporting transgressions to the responsible university of medical science.

In this Act, the physical requirements of the pharmacies have been considered too. For instance, in Article 33, the minimum physical space for daily and 24 h active pharmacies and warehouse conditions are mentioned.

Disciplinary investigation of professional violation

According to the Act of Medical Council of Iran,[9] in each strict, a disciplinary investigating committee consisted of a judge, representative of forensic medicine organization, five physicians, one dentist, one pharmacist, one laboratory medicine expert, one licensed expert, one nurse, and one midwife are responsible for investigating and judging the complaints of patients from guilt and professional violation of health-care providers.

REGULATION OF PHARMACEUTICAL TRADE-RELATED ASPECT

Pharmaceutical-related internal property rights

The enforcement of internal property rights (IPR) (patent law) in pharmaceutical market has been a controversial issue because it has some threats for the accessibility of poor population to essential medicines; nevertheless, it is considered as one of the innovation-driven factors which help innovative companies to compensate their R and D investment via a 20-year monopoly for a product.

Not being fully joined to the World Trade Organization, the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights agreement is not signed by Iran,[10] but the World Intellectual Property Organization agreement has been accepted. The patent, industrial designs, and trademarks registration law[11] has also been approved by parliament in 2008 encompassing many issues around IP and is currently under revision process. Domestic pharmaceutical companies however are enjoying the production of new Food and Drug Administration-approved and under patent products.

The electronic commerce act in pharmaceutical market

According to the E-commerce Act,[12] in the sale of pharmaceuticals and medical products to end customers, written document could not be replaced by data message; therefore, any types of pharmaceutical sale to patients and customers through the internet including online pharmacy are prohibited.

Antitrust and antidumping legislation

Although there is no unique antitrust law in Iran, but the related regulations are included in different articles of general policies of 44th principles of the constitution. According to these policies, a competition committee is authorized to monitor the market environment and interfere in any case of monopoly formation. In addition, the antidumping act was approved and implemented by the government in 2007.

Foreign investment in pharmaceutical industry

According to the Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Act (2002)[13] approved by the parliament, to promote the attendance of foreign investors in Iran's market, the total value of goods and services provided by foreign investment must be limited to 25% of the total values in that economic sector and 35% of subsector. Nevertheless, the foreign investments for export purposes (for industries other than oil) are exempted from this limitation.

CONCLUSION

Pharmaceutical legislation in Iran properly encompasses many aspects including the role of all stakeholders, registration process for both imported and domestic products, pricing, marketing and promotional activities, distribution channels, rational use of medicines, counterfeit medicines, national formulary and emergency centers, pharmacy practice, and even foreign investment in pharmaceutical industry. Nevertheless, some other legislative aspects of the pharmaceutical system have not received enough attention including the pharmacovigilance structure, remuneration and fee system for practical pharmacists, the balance between industrial and health objectives, substandard and low-quality medicines, and IPR rules and electronic health in the area of cyber medicine, online pharmacy, and public education.

To update the regulatory process, the MOH and FDO should try to assess the current legislation system to find out how much it has been effective to accomplish the goals of the national pharmaceutical policy and constitution and if needed, try to revise and develop new laws.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

PZ: Study design and manuscript writing and data collection, AHM: Study design and manuscript writing, MV: Checking the manuscript, HGH: Study design analysis, and data collection, IV: Study design analysis, HSZ: Study design analysis, SHE: Supervision on all study process, AK: Study idea and supervision on all study process.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fisk NM, Atun R. Market failure and the poverty of new drugs in maternal health. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trouiller P, Torreele E, Olliaro P, White N, Foster S, Wirth D, et al. Drugs for neglected diseases: A failure of the market and a public health failure? Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:945–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin S, Scott JT. The nature of innovation market failure and the design of public support for private innovation. Res Policy. 2000;29:437–47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. How to Design and Implement a National Drug Policy. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotfi K. Iran's drug industry in the past 80 years (Part 1) Chem Dev. 2000;4:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milanifar A, Akhondi MM, Paykarzadeh P, Larijani B. Assessing of conflict of interest in Iran's health legal system. Iran J Med Ethics. 2011;5:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osseini SA, Darbooy SH, Tehranibanihashemi SA, Naseri SM. Counterfeit medicines: Report of a cross-sectional retrospective study in Iran. Public Health. 2011;125:165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharif PS, Javadi M, Asghari F. Pharmacy ethics: Evaluation pharmacists’ ethical attitude. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2011;4:5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medical Council Law; 2004. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 09]. Available from: http://irimc.org/FileManager/IRIMCLaw.pdf?Lang=EN .

- 10.Hashemi Meshkini A, Kebriaeezadeh A, Dinarvand R, Nikfar S, Habibzadeh M, Vazirian I. Assessment of the vaccine industry in Iran in context of accession to WTO: A survey study. Daru. 2012;20:19. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-20-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patents, Industrial Designs and Trademarks Registration Act. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 15]. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details.jsp?id=7706 .

- 12.Electronic Commerce Law of the Islamic Republic of Iran. [Last accessed on 2014 May 23]. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/ir/ir008en.pdf .

- 13.Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Act (FIPPA) [Last accessed on 2014 May 21]. Available from: http://www.iran-investment.org/fippaen.pdf .