Abstract

Objective:

Drug promotional literatures (DPLs) are used as a promotional tool to advertise new drugs entering the market to doctors. The objective of the present study is to evaluate the accuracy of DPLs by using the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.

Methods:

An observational study was conducted from March to August 2014. The DPLs were collected from various departments at R.L. Jalappa Hospital and Research Centre attached to Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College, Kolar, India. The literature was evaluated based on 11 criteria laid down by the WHO.

Findings:

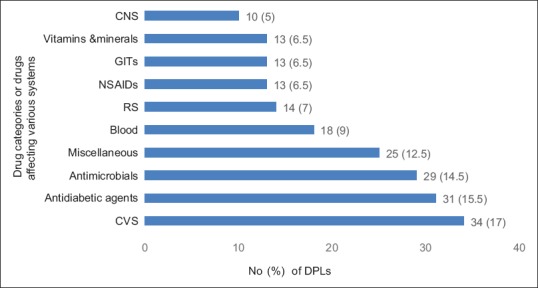

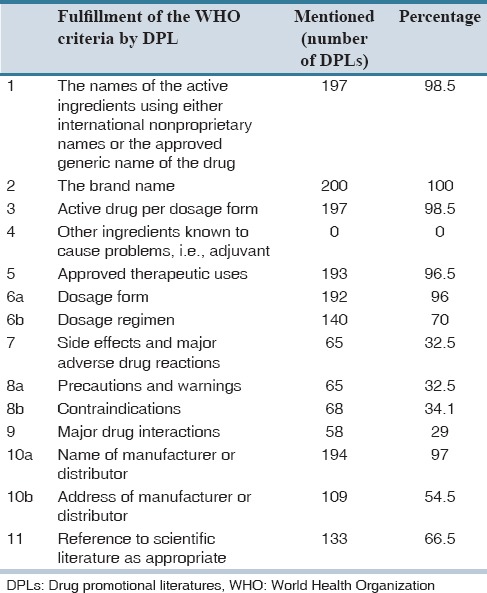

Two-hundred DPLs were evaluated. Cardiovascular drugs (34 [17%]) were promoted the most, followed by antidiabetic drugs (31 [15.5%]) and antimicrobial agents (29 [14.5%]). Single drug was promoted in 134 (67%) and fixed drug combination in 66 (33%) brochures. Manufacturer's name was mentioned in 194 (97%), but their address was mentioned in 109 (54.5%) claims only. Drug cost was revealed only in 12 (6%) DPLs. Each ingredient's generic name, brand name, and dosage form were mentioned in 197 (98%) brochures. Indication for use was stated in 193 (96.5%) claims. Contraindications, adverse effects, precautions, and drug interactions were listed in 68 (34.5%), 65 (32.5%), 65 (32.5%), and 58 (29%) advertisements. References were cited in 133 (66.5%) brochures. Only 63 (31.5%) literatures had relevant pictures of drugs being promoted and 59 (29.5%) had a graphical representation of pharmacological properties. A total of 131 (69%) DPLs followed 50% of the WHO criteria.

Conclusion:

Majority of DPLs satisfied only half of the WHO criteria for rational drug promotion and none of them fulfilled all the specified criteria. Incomplete or exaggerated information in DPLs may mislead and result in irrational prescription. Therefore, physicians should critically evaluate DPLs regarding updated scientific evidence required for quality patient care.

Keywords: Drug brochures, drug promotion, drug promotional literature

INTRODUCTION

Large number of new drugs are introduced into the market every day.[1] Pharmaceutical companies use drug promotional literatures (DPLs) as a major marketing tool to promote their new drugs.[2] DPLs are claimed to provide vital drug information and are being utilized to convince health professionals to prescribe the new drug.[3,4,5] Many a times, it is the only source on which treating physicians depend on for updating their knowledge about the existing and novel drugs.[6] In 2005, a pharmaceutical industry in the USA has spent more than 30 billion dollars in marketing and promoting to enlighten the clinicians about their products.[7] Such marketing influences clinician's prescribing behavior with or without benefitting the patient.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), medicinal drug promotion is defined as “all informational and persuasive activities by manufactures and distributors, the effect of which is to induce the prescription, supply, purchase, and/or use of medicinal drugs.”[8,9] Therefore, for the rational use of drugs, the WHO has laid down ethical criteria for medicinal drug promotion and has recommended pharmaceutical industries to implement these guidelines.[3] Organization of Pharmaceutical Producers of India, a self-regulatory code of pharmaceutical marketing practices, effective from December 2012, stated seven criteria which DPLs should follow.[10] Few studies have observed that information provided in DPLs are varying with the code of ethics.[11,12] This can affect the drug prescription, utilization, and sometimes can be irrational. Hence, this study was conducted to critically assess the accuracy of the promotional drug literature using the WHO guidelines.

METHODS

An observational study was conducted by the Department of Pharmacology at R.L. Jalappa Hospital and Research Centre attached to Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College, Kolar, India, for a period of 6 months from March to August 2014, after the protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. DPLs in the form of flyers, leaflets, and brochures were collected from various outpatient departments which were available in the hospital through medical representatives. Collected DPLs were assessed as per the WHO guidelines. Literature promoting medicinal devices and equipment (insulin pump, blood glucometer, and orthopedic prosthesis), ayurvedic medications, drug monographs, reminder advertisements, drugs’ name list, and literature promoting more than one drug or more than one fixed drug combination were excluded.

The following are the WHO criteria to be followed by pharmaceutical industries for the completeness of DPL:[13]

The names of the active ingredients using either international nonproprietary names or the approved generic names of the drug

The brand name

Content of active ingredient per dosage form or regimen

Name of other ingredients known to cause problems, i.e., adjuvant

Approved therapeutic uses

Dosage form or regimen

Side effects and major adverse drug reaction

Precautions, contraindications, and warnings

Major interactions

Name and address of the manufacturer or distributor

Reference to scientific literature as appropriate.

The DPLs were also analyzed for additional information such as various pictures printed, cost mentioned, and source and year of references used to defend the DPL claims. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. The data were expressed as percentage.

RESULTS

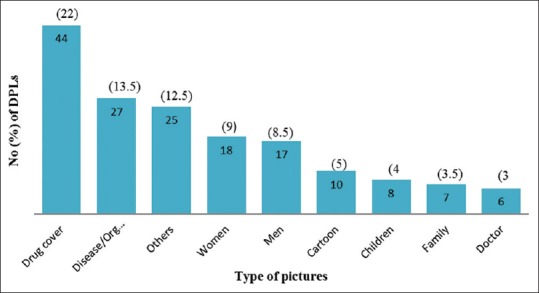

A total of 200 DPLs were collected and analyzed, which revealed 134 (67%) were single drug formulation and 66 (33%) were fixed dose combination. Figure 1 represents the most commonly promoted drug categories/or system wise. The extent to which DPLs followed the WHO criteria is shown in Table 1. Drug cost was revealed only in 12 (6%) brochures. Pictures occupied considerable amount of space on all brochures. DPLs depicted photographs of drug formulation, disease or organ, healthy/depressed men and women, and others as shown in Figure 2. Only 63 (31.5%) DPLs had relevant pictures of drugs being promoted and 137 (68.5%) had irrelevant representation in the form of car, women, men, and cartoons occupying major area. The pharmacological properties were represented in the form of graphs in 59 (29.5%) DPLs. The quality of paper used for DPLs were durable and the text was legible.

Figure 1.

Most commonly promoted drug categories/or system-wise. Miscellaneous: includes hormonal agents, immunomodulators, and antihistamines. CNS: Central nervous system; GITs: Gastrointestinal tract system; NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; RS: Respiratory system; CVS: Cardiovascular system; DPLs: Drug promotional literatures

Table 1.

Analysis of drug promotional literatures according to the World Health Organization criteria (n=200)

Figure 2.

Types of pictures depicted on DPLs. DPLs: Drug promotional literatures

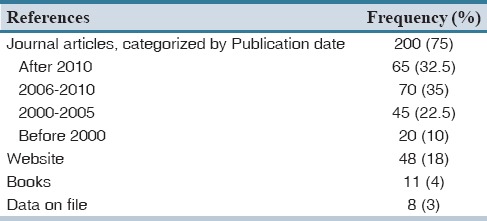

In 133 DPLs, 267 references were mentioned [Table 2]. Majority of references were quoted from journal articles, of which references published after 2010 were only 65 (32.5%) as represented in Table 2. Ten out of 11 criteria of the WHO were followed by 30 (15%) DPLs. A total of 131 (69%) brochures satisfied 50% of the WHO criteria. None of the brochures adhered to all the criteria.

Table 2.

Source of various references in the drug promotional literatures

DISCUSSION

Marketing new drugs to physicians is an important strategy adopted by pharmaceutical companies.[14] DPLs are sometimes the only source about new drugs/new indications for old drugs. In our study, it was observed that none of the DPLs fulfilled all the criteria laid down by the WHO guidelines. A similar finding was reported in other studies.[2,3,6,8] This suggests that drug promotional companies are more involved in establishing a commercial relationship with the treating physicians wherein ethical educational aspect is compromised.[2] In the present study, 33% of DPLs promoted fixed drug combination, hence the physicians should consider the rationality of the drug combination before prescribing.

Cardiovascular agents, antidiabetic drugs, and antimicrobials were among the top three groups of drugs being promoted, indicating that pharmaceutical companies are targeting diseases which are widely prevalent. This finding was in concordance with a study conducted in Mumbai.[1] Treating physicians should be highly cautious while prescribing the drugs based on information given in DPLs to avoid irrational prescription, higher incidence of drug resistance, adverse effects, and to reduce the cost incurred by patients.[1,15]

It was observed that most of the DPLs had mentioned brand name, approved generic name, and active ingredient per dosage form, which is similar to a study conducted in Nepal.[11] In our study, none of the brochures had mentioned other ingredients that are known to cause problems. We observed that majority of DPLs quoted dosage schedule and therapeutic indications, but did not stress on adverse drug reactions, precautions, contraindications, and interactions. The above criteria are certainly necessary for the care of the patient and also manage physician time from looking into other source of information. Similar findings were observed in other studies.[2,3,6,12,16,17]

All the brochures were colorful and attractive, but had irrelevant pictures related to the drugs being promoted. DPLs had used nonspecific representations occupying major area, which could have been utilized appropriately for listing various properties of drugs, other studies have reported similar finding.[2,3,8] In this study, it was observed that unsubstantiated claims were made in the brochures regarding efficacy and safety. Recent references were mentioned in very few DPLs, but this is essential for updating the clinicians so as to expand their existing knowledge and practice evidence-based medicine.

In view of this study, it is of utmost importance for the treating physician to critically evaluate any source of drug information based on the established guidelines before accepting them as scientific piece of information. Regional Ethics Committee in various metropolitan cities in India collect complaints about unethical drug promotion and report the same to the Drug Controller General of India to take necessary legal steps to regulate pharmaceutical companies to publish DPLs fulfilling the WHO criteria.[2,3,8,9]

Sixty-nine percent of the advertisements satisfied only half of the WHO criteria for rational drug promotion. Hence, the treating physicians should learn the art of analyzing DPL to provide quality care for the patients.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

P. Ganashree: Reviewing of literature, Data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. K. Bhuvana: Study design, Reviewing of literature and manuscript editing. N. Sarala: Data analysis and Manuscript review.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shetty VV, Karve AV. Promotional literature: How do we critically appraise? J Postgrad Med. 2008;54:217–21. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.41807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mali SN, Dudhgaonkar S, Bachewar NP. Evaluation of rationality of promotional drug literature using World Health Organization guidelines. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42:267–72. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.70020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khakhkhar T, Mehta M, Sharma D. Evaluation of drug promotional literatures using WHO guidelines. J Pharm Negative Results. 2013;4:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saxena D, Yadav P, Kantharia DN. Metaphors and symbols in drug promotional literature distributed by pharmaceutical companies. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;1:32–4. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.83288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zetterqvist AV, Mulinari S. Misleading advertising for antidepressants in Sweden: A failure of pharmaceutical industry self-regulation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phoolgen S, Kumar SA, Kumar RJ. Evaluation of the rationality of psychotropic drug promotional literatures in Nepal. J Drug Discov Ther. 2012;2:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornfield R, Donohue J, Berndt ER, Alexander GC. Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers and providers, 2001-2010. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadav SS, Dumatar CB, Dikshit RK. Drug promotional literatures (DPLs) evaluation as per World Health Organisation (WHO) criteria. J App Pharm Sci. 2014;4:84–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohra DK, Gilani AH, Memon IK, Perven G, Khan MT, Zafar H, et al. Critical evaluation of the claims made by pharmaceutical companies in drug promotional material in Pakistan. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2006;9:50–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Organization of Pharmaceutical Producers of India (OPPI) 2012. [Last cited on 2016 Feb 03]. Available from: http://www.indiaoppi.com/OPPI%20%Code%20of%20Marketing%202012.pdf .

- 11.Alam K, Shah AK, Ojha P, Palaian S, Shankar PR. Evaluation of drug promotional materials in a hospital setting in Nepal. South Med Rev. 2009;2:2–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper RJ, Schriger DL. The availability of references and the sponsorship of original research cited in pharmaceutical advertisements. CMAJ. 2005;172:487–91. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garje YA, Ghodke BV, Lalan HN, Senpaty S, Kumar R, Solunke S. Assessment of promotional drug literature using World Health Organization guidelines. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2014;4:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardarelli R, Licciardone JC, Taylor LG. A cross-sectional evidence-based review of pharmaceutical promotional marketing brochures and their underlying studies: Is what they tell us important and true? BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villanueva P, Peiró S, Librero J, Pereiró I. Accuracy of pharmaceutical advertisements in medical journals. Lancet. 2003;361:27–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlassov V, Mansfield P, Lexchin J, Vlassova A. Do drug advertisements in Russian medical journals provide essential information for safe prescribing? West J Med. 2001;174:391–4. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.6.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikhael EM. Evaluating the reliability and accuracy of the promotional brochures for the generic pharmaceutical companies in Iraq using World Health Organization guidelines. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7:65–8. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.148781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]