Abstract

E2F-mediated transcriptional repression of cell cycle–dependent gene expression is critical for the control of cellular proliferation, survival, and development. E2F signaling also interacts with transcriptional programs that are downstream of genetic predictors for cancer development, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Here, we evaluated the function of the atypical repressor genes E2f7 and E2f8 in adult liver physiology. Using several loss-of-function alleles in mice, we determined that combined deletion of E2f7 and E2f8 in hepatocytes leads to HCC. Temporal-specific ablation strategies revealed that E2f8’s tumor suppressor role is critical during the first 2 weeks of life, which correspond to a highly proliferative stage of postnatal liver development. Disruption of E2F8’s DNA binding activity phenocopied the effects of an E2f8 null allele and led to HCC. Finally, a profile of chromatin occupancy and gene expression in young and tumor-bearing mice identified a set of shared targets for E2F7 and E2F8 whose increased expression during early postnatal liver development is associated with HCC progression in mice. Increased expression of E2F8-specific target genes was also observed in human liver biopsies from HCC patients compared to healthy patients. In summary, these studies suggest that E2F8-mediated transcriptional repression is a critical tumor suppressor mechanism during postnatal liver development.

Introduction

The E2F family members form a core transcriptional axis crucial for coordinating cell cycle transitions. Traditionally, E2Fs have been categorized into 3 groups based on their transcriptional activity, expression, and regulation: activators (E2F1–3), canonical repressors (E2F4–6), and atypical repressors (E2F7/8; refs. 1–6). The different categories of E2Fs show distinct expression patterns during the cell cycle. The protein levels of E2F1–3 peak at the G1-S transition, whereas the levels of E2F7/8 peak later in S-G2, and levels of E2F4–6 remain constitutively high throughout all phases of the cell cycle (7). Functional studies in cell culture systems suggest that sequential binding of E2F activators and repressors to target promoters underlies the oscillatory nature of cell cycle–dependent gene expression (8–10), but in vivo data supporting this hypothesis are lacking.

Surprisingly, ablation of individual E2Fs in mice has little consequence for cell proliferation and animal development (7). However, the combined ablation of E2F1–3 or E2F7/8 leads to profound alterations in E2F target expression, severely compromising placental, fetal, and postnatal liver development (11–14), suggesting redundancy within specific E2F subcategories. Importantly, the simultaneous ablation of a single activator (E2F3A in placenta and E2F1 in liver) normalized gene expression and significantly ameliorated developmental phenotypes associated with loss of E2F7/8 atypical repressors (13, 14). These observations suggest that E2F activators and atypical repressors work in opposition to carefully regulate gene expression and promote the timely transition of cells through the cell cycle, which are necessary to maintain proper hepatocyte ploidy in vivo. Interestingly, liver-specific ablation of E2F1–3 or E2F7/8 leads to hepatocyte hyperploidy or hypoploidy, respectively, but with no apparent immediate physiological consequence for liver function (13, 15). Whether these perturbations in the E2F network impact organ physiology in adults is unknown (7).

In contrast with other E2Fs, E2F7/8 bind target promoters independently of physical interactions with dimerization partner proteins, and instead contain 2 tandem DNA binding domains that interact to form a single DNA binding surface that recognizes E2F consensus sequences (1–4). Atypical E2Fs are also unique in their ability to repress E2F-dependent gene expression without direct physical association with retinoblastoma gene product (RB1) and related pocket proteins (16). Thus, there appears to be RB1-dependent and -independent mechanisms to regulate the E2F transcriptional program. Transcription-independent functions have also been described for E2F8, including a cytoplasmic GTPase activity (17), but the physiological context for this novel aspect of E2F biology remains to be determined.

While the exact nature of how the E2F program is coordinated during animal development is only beginning to emerge, it is clear that disruption of the RB-E2F transcriptional network is a critical event downstream of many genetic alterations that promote cancer development, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (18, 19). Liver cancer, HCC being the predominant type, is currently the sixth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, with a strong male predilection (20, 21). Interestingly, elevated E2F8 expression has been observed in a variety of cancer types. Two recent reports implicate E2F8 in the activation of E2F target genes and in promoting the proliferation and tumorigenicity of human-derived lung and liver cancer cell lines (22, 23), suggesting an oncogenic role for this E2F family member.

Here we employed a genetic approach to alter E2F7 and E2F8 activities in the mouse to evaluate the impact of E2F7/8 in adult liver physiology. While liver function was remarkably normal, we observed a striking incidence of HCC in mice with increased E2F transcriptional output caused by either a loss of E2f7 and E2f8 or by a point mutation that disrupts E2F8’s DNA binding activity. Temporal-specific ablation of E2f8 in the liver suggests that E2F8’s tumor suppressor function is restricted to a critical time during early postnatal liver development. Furthermore, mechanistic studies identified a core set of putative direct E2F7/8 target genes whose increased expression is associated with progression to advanced HCC. In summary, gene ablation strategies suggest a cell-autonomous transcriptional repressor role for atypical E2Fs in hepatocytes of young mice that is dispensable for animal development yet critical to prevent HCC later in life.

Results

Increased expression of E2F7 and E2F8 in human HCC.

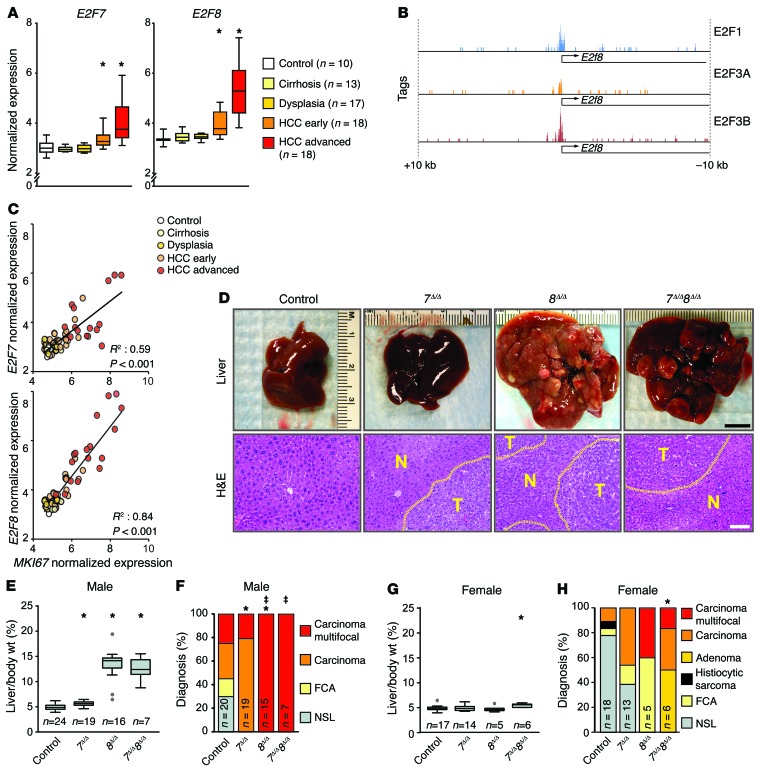

We initially explored the potential role of E2F7/8 signaling in cancer by querying COSMIC, TCGA, and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) databases for genetic and epigenetic alterations in these two E2F family members. Genetic alterations in E2F7 and E2F8 were infrequently observed in most solid tumor types, including HCC (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B; supplemental material available online with this article; doi:10.1172/JCI85506DS1). However, we found that E2F7 and E2F8 mRNA expression was elevated in patients with well-differentiated, early-diagnosed, and advanced HCC (Figure 1A and ref. 24). ChIP followed by next-generation sequencing (ChIP-seq) determined that E2F1 and E2F3A/B activators occupied consensus E2F binding sites on the E2f8 promoter near its transcriptional start site (TSS; Figure 1B), consistent with previous reports showing that atypical E2Fs can be transcriptionally autoregulated by E2Fs (1, 3). These observations indicated that E2F7 and E2F8 expression may be affected by the proliferative status of cells. As suspected, there was a tight correlation between the expression of the proliferative marker MKI67 (which encodes Ki-67) and the levels of E2F7/E2F8 mRNAs (Figure 1C), suggesting that elevated E2F7 and E2F8 expression is associated with hepatocyte proliferation in human HCC.

Figure 1. Loss of atypical E2Fs leads to carcinogen-induced HCC.

(A) Box plots showing the mRNA levels of E2F7 and E2F8 from patients with normal or diseased livers derived from Affymterix Microarrays, Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple tests. *, vs. control: E2F7 HCC-early, P = 0.020; HCC-advanced, P < 0.001; E2F8 HCC-early, P = 0.001; and HCC-advanced, P < 0.001. (B) Promoter occupancy of E2Fs on the E2f8 promoter. E2F1, E2F3A, and E2F3B tags were identified by ChIP-seq conducted in MEFs overexpressing E2F1, E2F3A, or E2F3B. (C) Correlation between expression of E2F7/8 and MKI67 mRNA levels in the data set described in A. P values, linear regression analysis. (D) Representative pictures of livers (top) and H&E-stained liver sections (below) from DEN-treated 9-month-old 7fl/fl 8fl/fl (control), Alb-Cre 7fl/fl (7Δ/Δ), Alb-Cre 8fl/fl (8Δ/Δ), and Alb-Cre 7fl/fl 8fl/fl (7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ) male mice. Areas of HCC are outlined by dotted lines. T and N, tumor and normal liver, respectively. Scale bars: 1 cm (top) and 100 μm (bottom). (E) Box plots showing the ratio of liver vs. body weight (liver/body wt.) of 9-month-old DEN-treated male mice. Outliers are represented by gray dots. Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction. *, vs. control: 7Δ/Δ, P = 0.009; 8Δ/Δ, P < 0.001; and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ, P < 0.001. (F) Histopathological analysis of livers from E. FCA, focal cellular atypia, NSL, no significant lesions. Fisher’s exact tests with Bonferroni’s correction. *, carcinoma (focal/multifocal) vs. control: 7Δ/Δ, P = 0.004; and 8Δ/Δ, P = 0.13. ‡, multifocal carcinoma vs. control: 8Δ/Δ, P < 0.001; and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ, P = 0.015. (G) Box plots showing liver/body wt. of 9-month-old DEN-treated female mice. Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction. *, 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ vs. control, P < 0.001. (H) Histopathological analysis of livers from G. Fisher’s exact tests with Bonferroni’s correction. *P = 0.026, carcinoma vs. control. n, number of mice or patients per group.

Atypical E2F7 and E2F8 are tumor suppressors in the mouse liver.

The above observations raised the possibility of an involvement of E2F7 and E2F8 in HCC. Previous work identified a critical role for E2F7 and E2F8 in endoreduplication of hepatocytes of mice (13, 15). Deletion of E2f7 and E2f8 in mouse hepatocytes resulted in altered gene expression programs and decreased ploidy, but the long-term physiological consequences of lacking E2f7 and E2f8 were not evaluated. We thus used the albumin-Cre (Alb-Cre; ref. 25) transgene and conditional alleles of E2f7 and E2f8 (E2f7fl/fl and E2f8fl/fl; ref. 10) to test their role in HCC development. Cohorts of control, Alb-Cre E2f7fl/fl (referred to hereafter as 7Δ/Δ), Alb-Cre E2f8fl/fl (referred to hereafter as 8Δ/Δ), and Alb-Cre E2f7fl/fl E2f8fl/fl (referred to hereafter as 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ) male and female mice were treated with the liver-specific carcinogen diethylnitrosamine (DEN; ref. 26) and examined at 9 months of age. Deletion of E2F7/8 in livers was confirmed by PCR genotyping (Supplemental Figure 1C). Surprisingly, livers from 8Δ/Δ and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ male mice had a striking nodular appearance, whereas livers from control and 7Δ/Δ mice appeared phenotypically normal. Moreover, liver weights were dramatically increased in 8Δ/Δ and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ male mice (>2.5-fold) relative to either 7Δ/Δ or control mice (Figure 1, D and E). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained tissue sections showed that 55% of control and 100% of 7Δ/Δ male mice had single microscopic lesions of well-differentiated HCC, whereas 100% of 8Δ/Δ and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ mice exhibited macroscopic visible multifocal carcinomas (Figure 1, D and F). Female 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ mice also had increased incidence of HCC relative to controls, but consistent with the known gender bias in humans (27), tumor grade and burden were reduced in females relative to males of the same genotype (Figure 1, G and H).

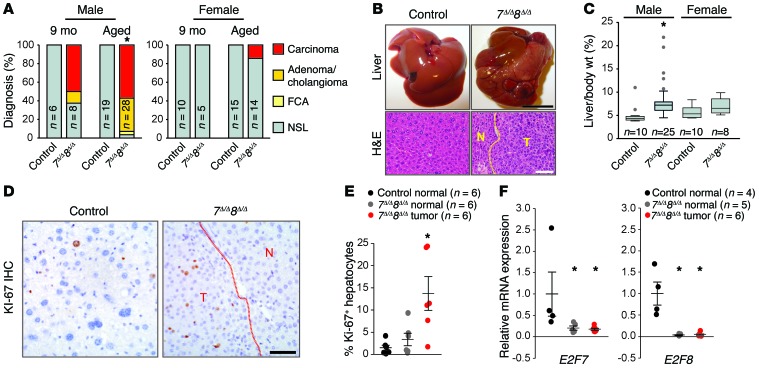

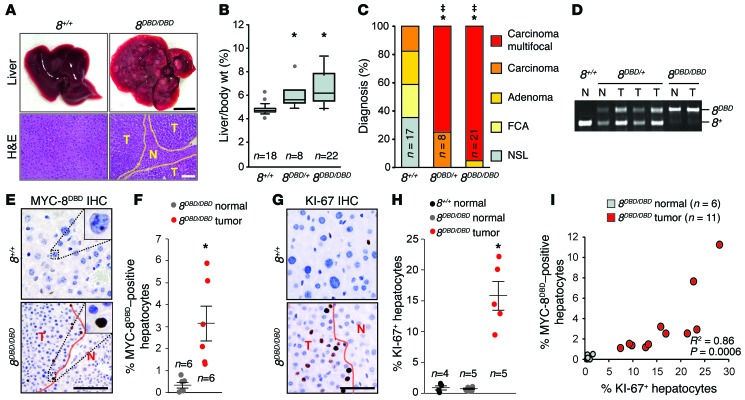

We also evaluated spontaneous development of HCC in cohorts of control and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ male and female mice at 9 months of age and just prior to death (upon reaching early-removal IACUC criteria). At 9 months of age, 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ livers appeared normal except for the occasional presence of small external nodules. Histopathologic analysis revealed microscopic HCC and/or adenoma in 62.5% (5 of 8) of 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ male mice, but no lesions in control littermates (Figure 2A). Control and littermate 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ male and female mice had similar lifespans (Table 1). At time of natural death (aged), 93% of 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ male mice (26 of 28) had HCC/adenoma and increased hepatic weights, whereas all control mice remained tumor free (0 of 34; Figure 2, A–C). Spontaneous tumors were highly proliferative as indicated by increased KI-67 positivity (Figure 2, D and E). RNA expression of E2f7 and E2f8, as measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR), confirmed that liver tumors in 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ males arose from deleted hepatocytes (Figure 2F). Finally, as in DEN-treated mice, there was a higher incidence of spontaneous liver tumors in 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ males than females (Figure 2, A and C). Thus, loss-of-function mouse models show that E2F8, and to a lesser extent E2F7, function as tumor suppressors by protecting mice from both carcinogen-induced and spontaneous HCC.

Figure 2. Loss of atypical E2Fs in hepatocytes leads to spontaneous HCC.

(A) Histopathological analysis of livers at 9 months of age or at time of natural death (aged) of control or 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ mice. Fisher’s exact tests were conducted between control and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ samples comparing carcinoma (focal and multifocal) to no significant lesion (NSL); *P = 0.004. FCA, focal cellular atypia. (B) Representative pictures of livers (top) and H&E-stained liver sections (below) from controls or 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ male mice at time of natural death. Scale bars: 1 cm (top) and 100 μm (bottom). (C) Box plots showing the liver/body wt. from control or 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ male and female mice at time of natural death. 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ males, P < 0.001; Wilcoxon tests. (D) IHC for KI-67 showing proliferating hepatocytes in control normal liver, 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ normal liver, and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ tumor tissue from male mice at time of natural death. Scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Quantification of the KI-67 IHC in D. At least 100 hepatocytes were counted for each liver. Dots represent values for individual mice and lines represent means ± SEM. Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple tests; *P = 0.026 for 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ tumor samples vs. control. (F) mRNA levels of E2f7 and E2f8 in control normal liver and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ tumor and adjacent normal tissue from male mice at time of natural death measured by qPCR. Dots represent values for individual mice and lines represent means ± SEM. Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction. E2F7: 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ normal vs. control, P = 0.04; and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ tumor vs control, P = 0.028. E2F8: 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ normal vs. control, P = 0.04; and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ tumor vs. control, P = 0.028. n, number of mice in each group.

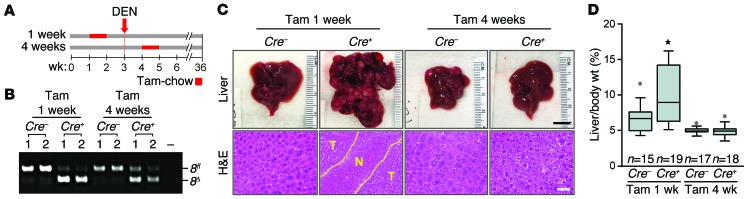

Table 1. Life span of control and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ mice.

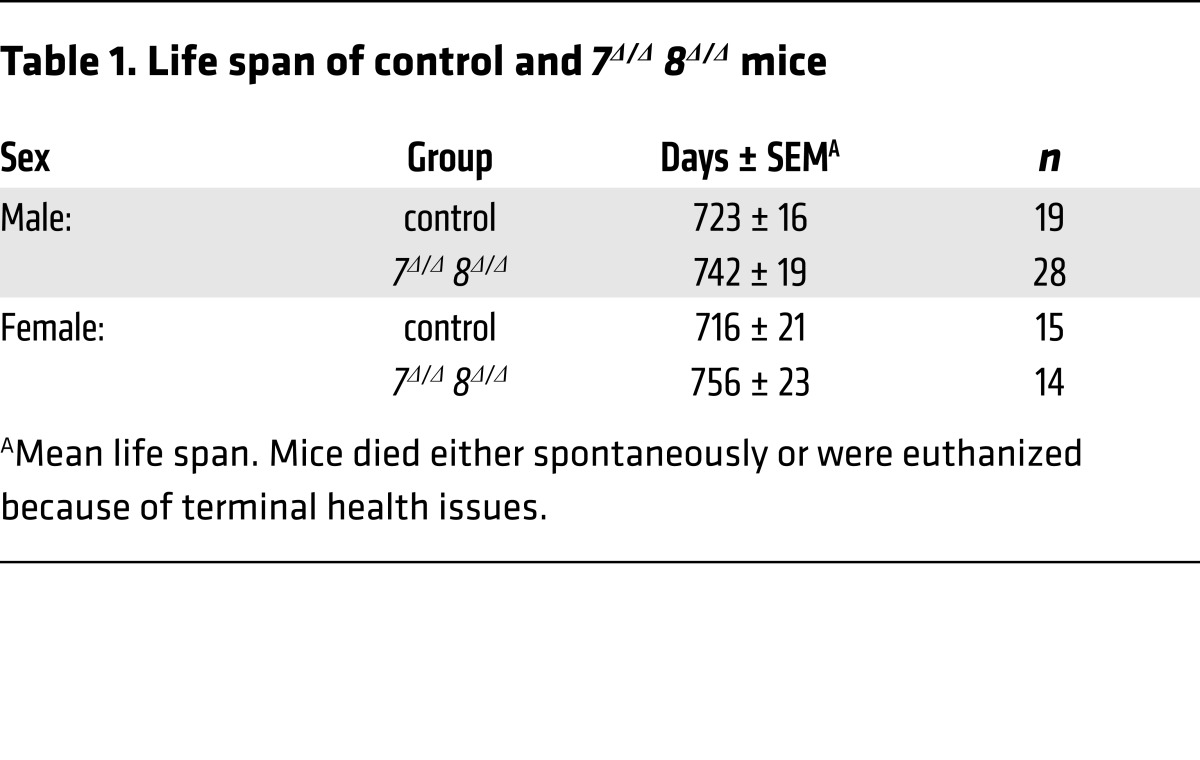

Tumor suppression by E2F8 is confined prior to adolescence.

The expression of E2f8 in livers is relatively high during embryonic development and in newborn pups, but is extinguished by 4 weeks of age (13, 15). This earlier observation prompted us to functionally evaluate E2f8’s tumor suppressive role either early or late during postnatal liver development. To this end, we utilized a tamoxifen-inducible Alb-Cre transgene (Alb-CreERT2; ref. 28) and a tamoxifen-chow diet to delete E2f8 in hepatocytes after 1 week of age, when hepatocytes are rapidly dividing, or after 4 weeks of age, when bulk hepatocytes have exited the cell cycle and become quiescent. The experimental regimen used is depicted in Figure 3A; Alb-CreERT2 E2f8fl/fl mice (Cre+) and control E2f8fl/fl littermates (Cre–) were switched from a standard diet to a tamoxifen-chow diet at either 1 week (in cages with a nursing mother) or 4 weeks of age. All mice were treated with DEN and then harvested at 9 months of age. Deletion of E2f8 was confirmed by PCR genotyping of genomic DNA from nontumor and tumor tissues (Figure 3B). Analysis of livers showed that ablation of E2f8 at 1 to 2 weeks of age, but not at 4 to 5 weeks, resulted in visible multifocal carcinoma and increased hepatic mass (Figure 3, C and D); histopathology confirmed lesions to be HCC (Figure 3C). Together, these analyses defined the tumor suppressor role of E2F8 as occurring at a critical window of time during early postnatal liver development when hepatocytes are highly proliferative.

Figure 3. E2F8 tumor suppressor function during early postnatal development.

(A) Diagram illustrating the temporal deletion of E2f8 using Alb-CreERT2 E2f8fl/fl (Cre–) and Alb-CreERT2 E2f8fl/fl (Cre+) male littermates were fed tamoxifen chow (Tam) for 7 days, starting at their first and fourth week of life. DEN was administered to all mice at 20 days of age and mice were harvested at 9 months of age. (B) PCR genotyping of liver samples from 9-month-old DEN-treated Cre– and Cre+ male mice. The 8fl (670 bp) and the 8Δ band (500 bp) are noted. (C) Representative pictures of livers (top) and H&E-stained liver sections (below) from 9-month-old DEN treated Cre– and Cre+ male mice. Areas of HCC are outlined by dotted lines. T and N, tumor and normal liver, respectively. Scale bars: 1 cm (top) and 100 μm (bottom). (D) Box plots showing the liver/body wt. of mice from C. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t tests comparing Cre– and Cre+ groups; *P = 0.007. n, number of mice in each group.

E2F8 function in development is dependent on an intact DNA binding domain.

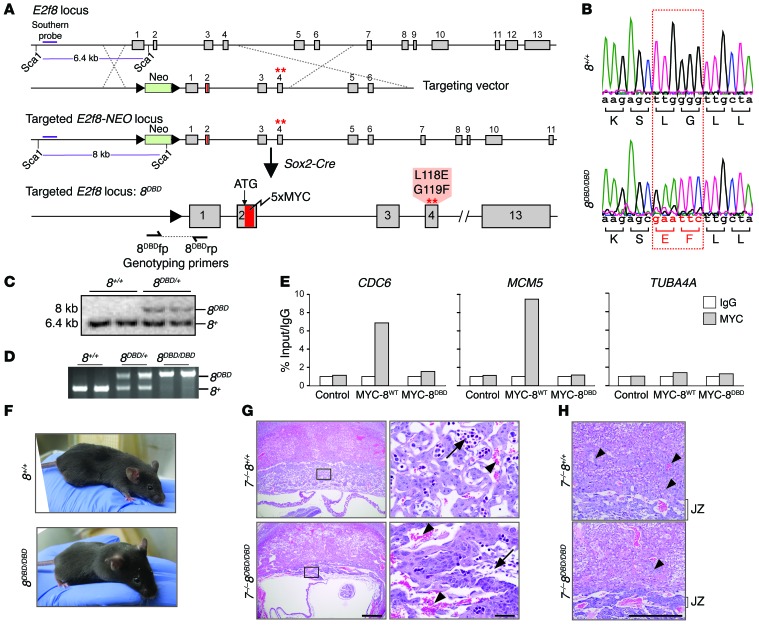

E2F8 is a nuclear factor with DNA binding activity, but may also have cytoplasmic GTPase activity independent of its role as a transcription factor (17). To understand E2F8’s physiological function in vivo, we used standard homologous recombination approaches in mice to introduce 2 missense mutations in the first DNA binding domain (DBD) encoded within exon 4 of E2f8 (Figure 4, A and B). These two missense mutations (L118E and G119F) have been previously shown to disrupt E2F8 DNA binding in vitro (3). Because robust mouse E2F8-specific antibodies were not available for immunohistochemistry (IHC), sequences encoding an N-terminal 5×MYC tag were introduced into the targeting vector. Sequencing of genomic DNA, Southern blot, and PCR genotyping confirmed correct integration of the mutant DBD allele (E2f8DBD, hereafter referred to as 8DBD) into mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells (Figure 4, B–D). Targeted ES cells were then used to generate knockin mice carrying the 8DBD allele, and positive offspring were bred with Sox2-Cre mice to remove the LoxP-flanked neomycin selection cassette. ChIP-qPCR in HepG2 cells demonstrated that the 5×MYC tag does not interfere with the DNA binding activity of wild-type E2F8 protein (MYC-8WT) and that E2F8 protein with missense mutations in the DNA binding domain (MYC-8DBD protein) is incapable of binding to target promoters (Figure 4E and Supplemental Figure 2A).

Figure 4. DNA binding activity is required for E2F8 function during development.

(A) Diagram of the mouse E2f8 locus, targeting vector, and targeted E2f8 locus prior to and after germ line deletion of the neomycin (NEO) cassette using Sox2-Cre. A 5×MYC tag (red) was inserted after the ATG and the first DNA binding domain (DBD1) was mutated; amino acid changes are noted. Dashed lines show homologous recombination between targeting vector and endogenous locus. The purple line represents the Southern probe used to test embryonic stem (ES) cell clones after Sca1 digestion. (B) Sequencing histogram of wild-type (8+/+) and 8DBD/DBD mice showing the mutation in DBD1 of E2f8. Altered nucleotides and resulting amino acid changes are shown in red. (C) Southern blotting for the E2f8+ and E2f8DBD alleles in ES cells. (D) PCR genotyping of DNA from 8+/+, 8DBD/+, and 8DBD/DBD mice using primers flanking the LoxP site shown in A. The 8DBD (320 bp) and 8+ (209 bp) bands are noted. (E) ChIP-qPCR using IgG or MYC antibodies in HepG2 cells (control) or HepG2 cells expressing 5×MYC-tagged wild-type E2F8 (MYC-8wt) or 5×MYC-tagged DBD E2F8 (MYC-8DBD). CDC6 and MCM5 are established E2F targets; TUBA4A is shown as a negative control. Percentage of input values for MYC-tagged E2F8 were normalized to IgG. (F) Pictures of 8+/+ and 8DBD/DBD mice. (G) H&E-stained sections from E10.5 7–/– 8+/+ and 7–/– 8DBD/DBD placentation sites illustrating altered placental architecture with a disruption in fetal capillary formation and pooling of maternal blood in 7–/– 8DBD/DBD placentas. Arrows, fetal blood vessels. Arrowheads, maternal blood sinuses. Scale bars: 500 μm (left) and 50 μm (right). (H) Higher magnification of sections from G illustrating altered placental architecture with compaction of the placental junctional zone (JZ) and limited trophoblast invasion (arrowheads) in 7–/– 8DBD/DBD placentas. Scale bar: 500 μm.

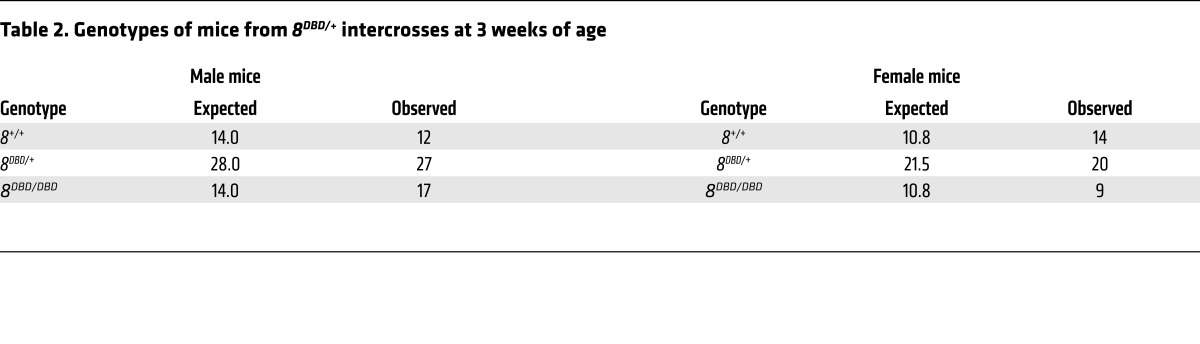

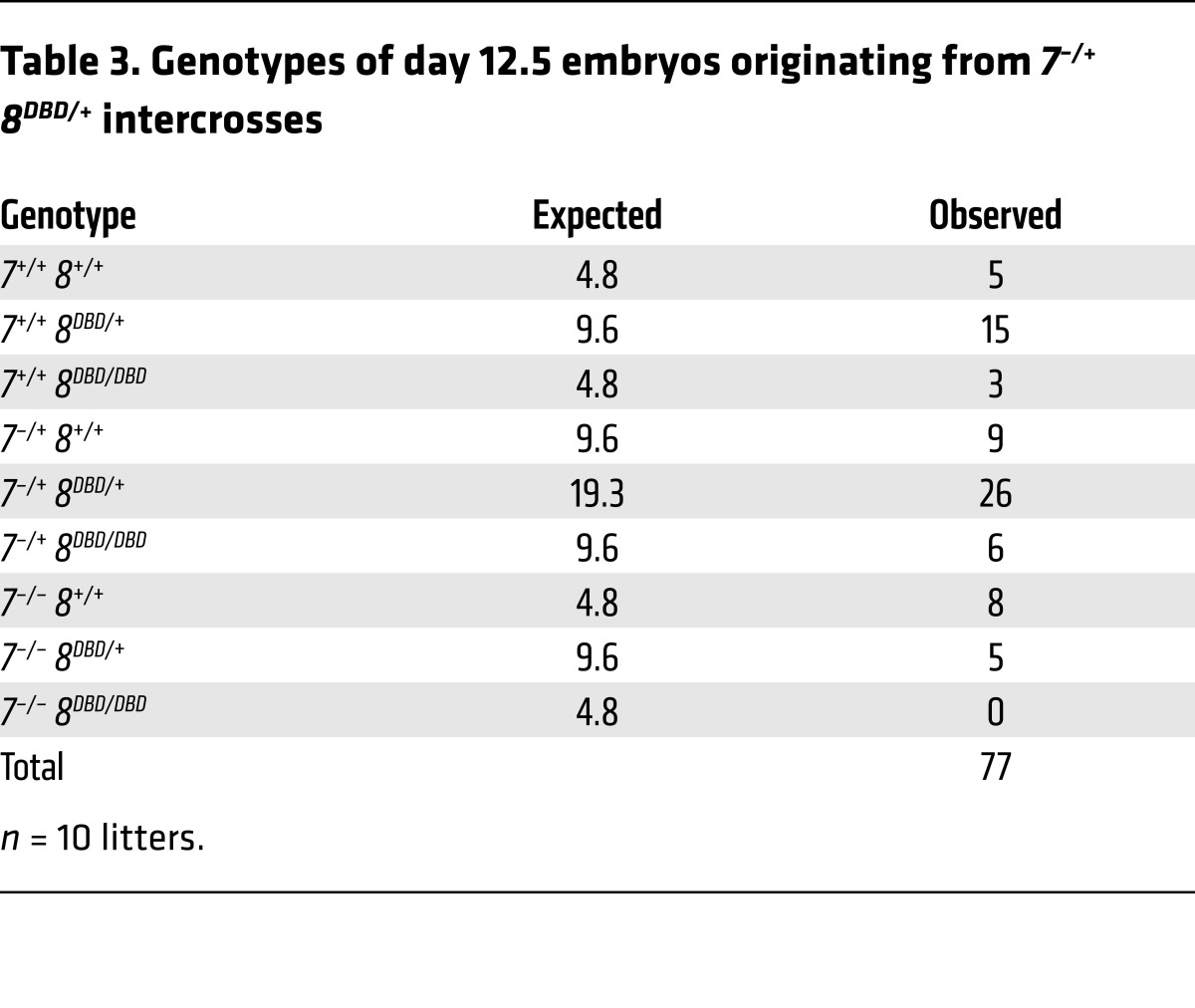

Interbreeding heterozygous 8DBD/+ mice yielded Mendelian ratios of viable, healthy, and fertile 8DBD/DBD males and females (Figure 4F and Table 2). Previous analyses showed that the presence of one atypical E2F is sufficient for embryonic development but loss of both results in embryonic lethality by embryonic day 11.5 (E11.5; ref. 10). When 8DBD mice were bred into an E2f7 null background (E2f7–/–, referred to hereafter as 7–/–), 7–/– 8DBD/DBD embryos died by E11.5 and while some 7–/– 8DBD/+ embryos could be carried to term, these pups had reduced postnatal viability (Table 3 and Supplemental Figure 2B). Assessment of live E10.5 embryos showed that 7–/– 8DBD/DBD placentas were smaller than controls and had a severely compromised architecture, with poorly formed fetal vasculature and densely packed trophoblast cells that failed to effectively invade into the maternal decidua (Figure 4, G and H). Thus, 8DBD/DBD mice phenocopied developmental and cellular defects observed in 8–/– mice.

Table 2. Genotypes of mice from 8DBD/+ intercrosses at 3 weeks of age.

Table 3. Genotypes of day 12.5 embryos originating from 7–/+ 8DBD/+ intercrosses.

E2F8 function in liver development is dependent on an intact DNA binding domain.

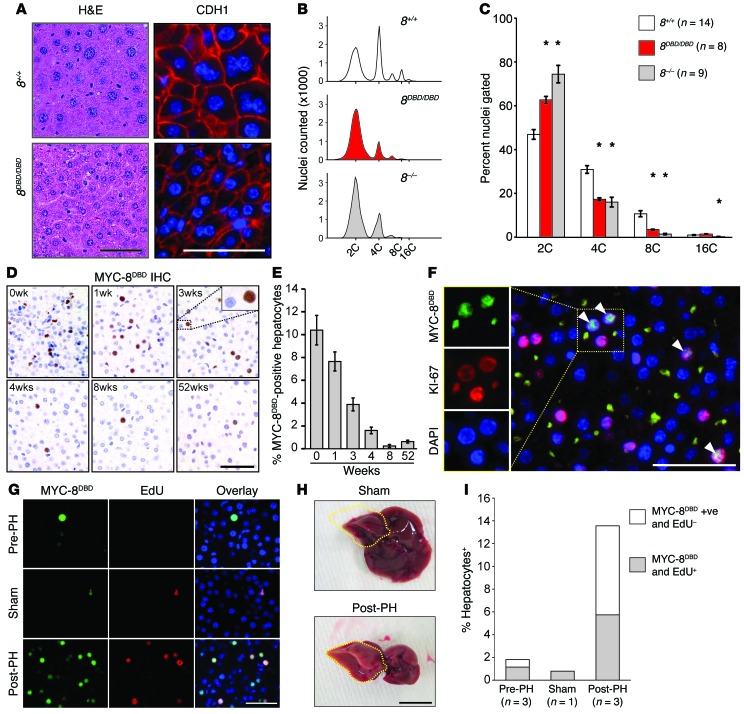

Previous work from our laboratory showed that E2F8 is critical for polyploidy and that its loss from the liver is sufficient to block hepatocyte endoreduplication, resulting in diploid cells (13, 15). Hepatocytes in adult 8DBD/DBD mice also had uniformly smaller nuclei and reduced ploidy relative to wild-type controls (Figure 5, A–C), indicating that endoreduplication was severely compromised. We then used MYC tag–specific antibodies to evaluate the expression of MYC-tagged E2F8DBD protein in hepatocytes of newborn, 1- to 8-week-old, and 1-year-old 8DBD/DBD mice by IHC. This analysis showed that the 8DBD protein was exclusively localized in the nucleus (Figure 5D), suggesting that the 2–amino acid substitution in the DBD did not disrupt subcellular trafficking or overall protein conformation. Importantly, the number of hepatocytes expressing 8DBD protein decreased following birth and by 4 weeks of age was almost undetectable (Figure 5, D and E). Coimmunofluorescence demonstrated that 8DBD was exclusively expressed in KI-67–positive proliferating hepatocytes (Figure 5F). 8DBD protein was also expressed in proliferating hepatocytes following partial hepatectomy (Figure 5, G–I). These findings show that E2F8 protein expression is limited to proliferating cells in developing livers and in response to liver damage.

Figure 5. E2F8 DNA binding activity is essential for endoreduplication.

(A) Histology of livers from 12-month-old 8+/+ and 8DBD/DBD mice. H&E-stained sections (left), immunofluorescence (IF; right) for cadherin 1 (CDH1) (red) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars: 50 μm. (B) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting profiles of propidium iodide–stained liver nuclei from 4-month-old 8+/+, 8DBD/DBD, and 8–/– mice. (C) Nuclear liver ploidy of mice from B. Bars represent means ± SEM. Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple tests. *, 8DBD/DBD and/or 8–/– vs. 8+/+. For 8DBD/DBD: 2C, P = 0.002; 4C, P < 0.001; and 8C, P < 0.001. For 8–/–: 2C, P < 0.001; 4C, P = 0.001; 8C, P < 0.001; and 16C, P = 0.002. (D) IHC using Myc epitope–specific antibodies that recognize the expression of 5×Myc-tagged 8DBD (MYC-8DBD) in livers of 8DBD/DBD mice at the indicated ages. Scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Quantification of MYC-8DBD expression in D. Average percentage of positive hepatocytes per ×40 field ± SEM for 2 livers for 0 to 8 weeks and 1 liver for 52 weeks. At least 640 hepatocytes were counted per liver. (F) IF for MYC-8DBD (green), KI-67 (red), and DAPI (blue) in livers of 3-week-old 8DBD/DBD mice. Colocalization of 8DBD and KI-67 (arrowheads). Scale bar: 50 μm. (G) IF for MYC-8DBD (green), EdU (red), and DAPI (blue) of liver sections from tissue removed during partial hepatectomy (Pre-PH), from sham surgery mice (Sham), or regenerating tissue 32 hours after partial hepatectomy (Post-PH). Scale bar: 50 μm. (H) Representative pictures of Sham- and Post-PH–treated livers. The right lobe (which was not excised) is outlined in yellow. Scale bar: 1 cm. (I) Quantification of MYC-8DBD–positive and EdU-positive hepatocytes from livers described in G. At least 100 hepatocytes were counted per liver. n, number of mice per group.

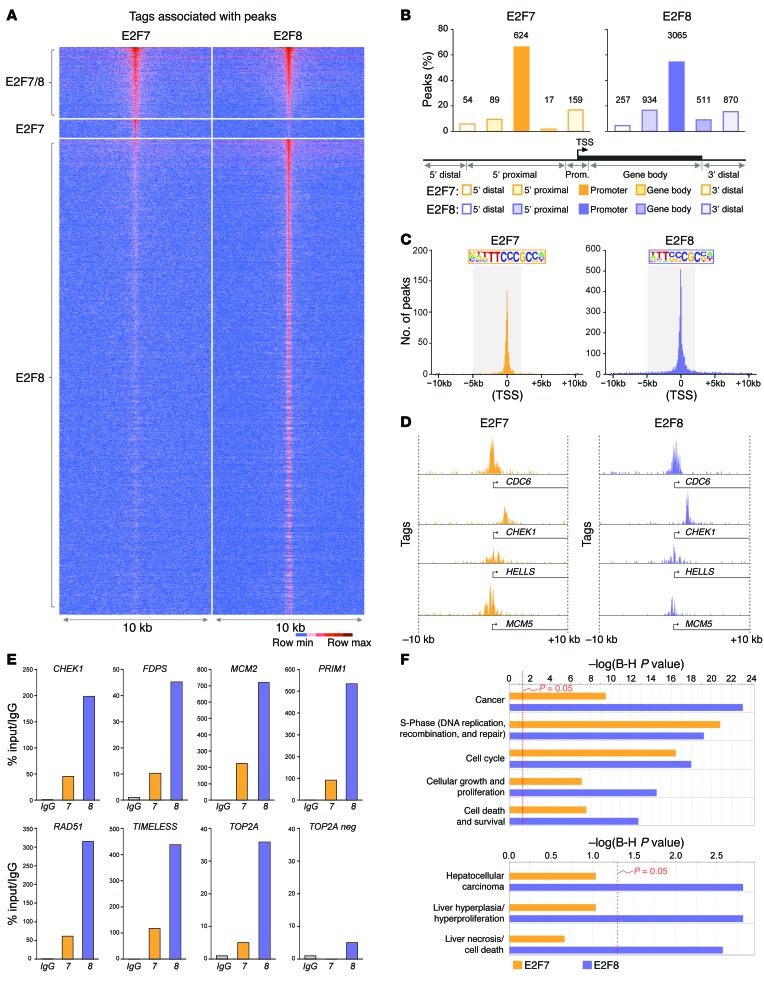

E2F8 DNA binding activity is essential for tumor suppression.

Liver cancer was then evaluated in 8DBD/+, 8DBD/DBD, and wild-type littermate control males treated with DEN. At 9 months of age, 8DBD/DBD mice displayed multiple visible liver tumors characterized as multifocal carcinoma and had increased hepatic mass compared to controls (Figure 6, A–C). Analysis of heterozygous 8DBD/+ mice showed an intermediate burden of liver cancer (Figure 6, B and C). PCR genotyping of genomic DNA showed that 8DBD/+ liver tumors retained a wild-type E2f8 allele (Figure 6D), suggesting haploinsufficiency. These findings demonstrate that intact DNA binding activity is essential for E2F8’s tumor suppressor function in hepatocytes.

Figure 6. E2F8 DNA binding activity is essential for tumor suppression.

(A) Representative pictures of livers (top) and H&E-stained sections (bottom) from 8+/+ and 8DBD/DBD DEN-treated 9-month-old male mice. Areas of HCC are outlined by dotted lines. T and N, tumor and normal liver, respectively. Scale bars: 1 cm (top) and 100 μm (bottom). (B) Box plots showing the liver/body wt. of mice from A. Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple tests. *, vs. 8+/+ livers. 8DBD/+, P = 0.002; 8DBD/DBD, P < 0.001. (C) Histopathological analysis of livers from A. Fisher’s exact tests with Bonferroni’s correction. *, carcinoma (focal and multifocal) vs. 8+/+. 8DBD/+, P = 0.001 and 8DBD/DBD, P < 0.001. ‡, multifocal carcinoma vs. 8+/+. 8DBD/+, P < 0.001; 8DBD/DBD, P < 0.001. FCA, focal cellular atypia, NSL, no significant lesions. (D) Genotyping PCR of normal and tumor liver samples from A. (E) IHC using Myc epitope–specific antibodies that recognize the expression MYC-8DBD in livers from A. Scale bar: 50 μm. (F) Quantification of MYC-8DBD expression from E. At least 180 hepatocytes were counted per liver. Dots indicate values for individual mice and lines indicate mean ± SEM. Student’s t tests comparing 8DBD/DBD normal vs. 8DBD/DBD tumor samples. *P = 0.016. (G) IHC for KI-67 in livers from A. Scale bar: 50 μm. (H) Quantification of KI-67 expression from G. At least 210 hepatocytes were counted per liver. Dots indicate values for individual mice and lines indicate mean ± SEM. Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction. *P = 0.04 for 8DBD/DBD tumor vs. 8+/+ normal. (I) Correlation between the percentage of cells expressing MYC-8DBD and KI-67 in normal and tumor areas. Each circle represents the percentage of positive hepatocytes in one ×40 field. R2 = Spearman’s rho P values were used to determined correlation between MYC-8DBD and KI-67 expression. n, number of mice per group.

Importantly, we found a strong positive correlation between 8DBD and KI-67 protein levels in these mouse tumor samples (Figure 6, E–I). Furthermore, the immunostaining intensity of 8DBD protein was similar in proliferating hepatocytes of normal livers (3-week-old) and tumor bearing livers (9-month-old; Supplemental Figure 3). Together, these observations suggest that the ‘apparent increase’ in E2F8 expression observed in a number of cancer types, including HCC, may simply reflect increased numbers of proliferating cells present in tumors and not a cancer-driving event as previously suggested (22, 23).

ChIP-seq defines overlapping E2F7/8 chromatin binding landscapes.

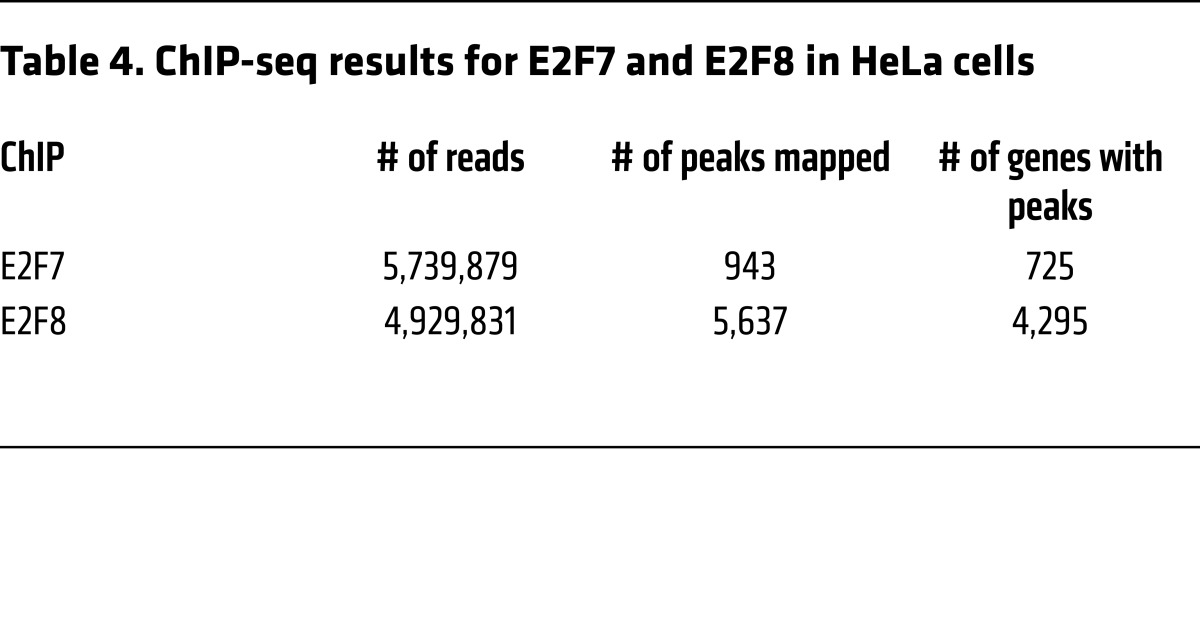

Given the established role of atypical E2Fs as transcriptional repressors and our findings above that E2F8 DNA binding activity was critical for tumor suppression, we sought to determine the chromatin binding landscapes of E2F7 and E2F8 by ChIP-seq. ChIP-seq with E2F7-specific antibodies was performed previously (ref. 29; GEO: GSE32673) in asynchronously proliferating HeLa cells. We thus employed a similar protocol to immunoprecipitate E2F8-bound genomic DNA and prepare libraries for next-generation sequencing. DNA sequencing tags were mapped to the human genome and peak summits were identified using MACS algorithms (Table 4). Genome-wide E2F7 and E2F8 unique and shared peaks are illustrated in Figure 7A. Most peaks were positioned within promoter regions (defined as –5 kb to +2 kb from the transcriptional start site [TSS]; Figure 7B and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). E2F-binding consensus sequences were enriched within peaks at promoter regions (Figure 7, C and D; Supplemental Figure 4A; and ref. 29). Binding of E2F7 and E2F8 to selected target promoters in HeLa cells was validated by ChIP-qPCR in an HCC-derived tumor cell line (HepG2) and an established hepatocyte cell line (THLE-2) (Figure 7E and Supplemental Figure 4B). Functional annotation using ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) revealed that E2F7 and E2F8 putative target genes are enriched for functions related to cell cycle, cell growth, S phase, and cell death and survival (Figure 7F and Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Remarkably, when liver-specific functions were queried, only E2F8 targets were significantly involved in HCC, liver proliferation, and necrosis, consistent with E2F8’s prominent role in tumor suppression.

Table 4. ChIP-seq results for E2F7 and E2F8 in HeLa cells.

Figure 7. Identification of HCC-relevant E2F targets by ChIP-seq.

(A) Tag-intensity heat map showing the distribution of tags for all E2F7 and E2F8 peaks identified by ChIP-seq. Peaks were centered on E2F8-specific samples except for peaks that were specific to E2F7. (B) Percentage of E2F7- and E2F8-specific peaks in different gene regions. Gene regions were defined by distance from the transcriptional start site (TSS) as follows: 5′ distal (–50 Gb to –50 kb), 5′ proximal (–50 kb to –5 kb), promoter (–5 kb to +2 kb), gene body (+2 kb to end of transcript), 3′ distal (end of transcript to +30 Gb). Number of peaks for each gene region is indicated above bars. (C) Graph depicting the frequency of E2F7 and E2F8 tags relative to the TSS (0). The promoter region (–5 kb to +2 kb from the TSS) is highlighted and the consensus binding sequence at the promoter identified by HOMER is depicted. (D) Examples of E2F7 and E2F8 occupancy at selected promoters. (E) ChIP-qPCR validation using IgG, E2F7, or E2F8 antibodies in HepG2 cells. Selected target promoters are shown (CHEK1, FDPS, MCM2, PRIM1, RAD51, TIMELESS, and TOP2A). A nonpromoter region of TOP2A (TOP2A neg) was used as a negative control. % input values were normalized to IgG. Primers were designed to amplify ChIP-seq–identified peak regions. (F) Gene ontology using ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) software depicts the estimated contribution of gene functions associated with E2F7- or E2F8-bound promoters. Functional categories related to cell cycle, cancer, and liver disease with the lowest P values are shown. Bars indicate the Benjamini-Hochberg–adjusted (B-H) P value; the threshold of P = 0.05 is shown.

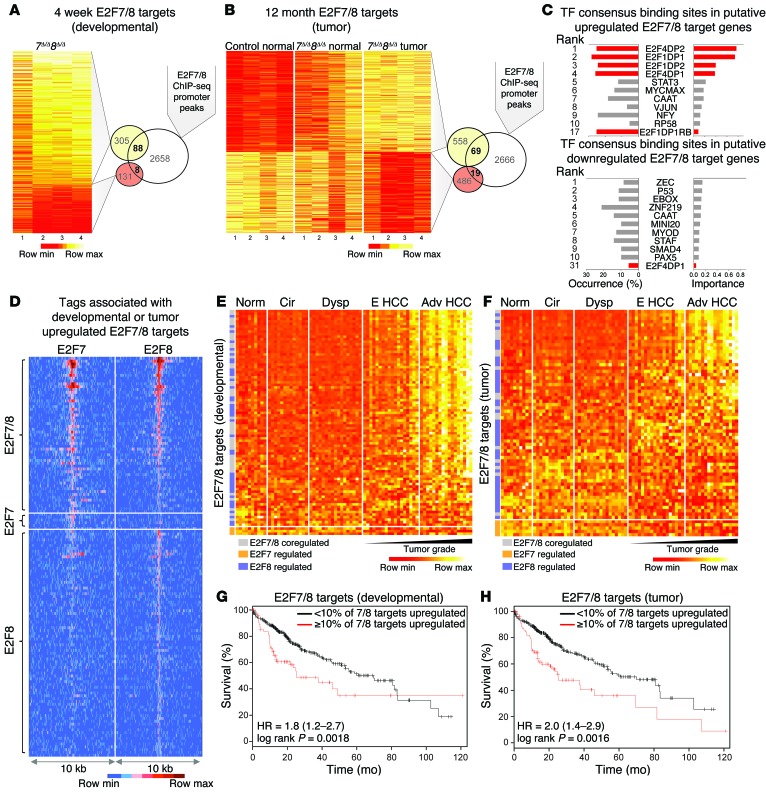

Increased expression of E2F7/8 coregulated targets is associated with human HCC.

We hypothesized that increased E2F transcriptional output due to ablation of E2F7/8 may drive HCC development. Thus, we profiled mRNA expression in livers from 4-week-old control and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ mice (15) and in 12-month-old control (normal) and 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ mice (normal and tumor tissue). Differentially expressed genes at 4 weeks (developmental) and 12 months of age (tumor) are presented as heat maps in Figure 8, A and B, respectively (≥ 1.5-fold vs. control and FDR ≤ 0.05; Supplemental Table 5). We overlapped gene expression and ChIP-seq data sets to identify putative direct targets of E2F7/8 (Figure 8, A and B, and Supplemental Tables 6 and 7). Interestingly, sequence analysis of putative direct-target promoters showed that upregulated but not downregulated targets contained bona fide E2F consensus binding sequences (Figure 8C). These observations are consistent with E2F7 and E2F8 functioning primarily as transcriptional repressors of E2F target genes.

Figure 8. Identification of putative direct targets of E2F7/8 and evaluation of their relevance to human disease.

(A) Fold-change heat map of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in livers from 4-week-old 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ and control mice measured by Agilent Microarrays. DEGs are defined as having ≥ 1.5-fold change vs. control (P ≤ 0.05). Overlap of DEGs and E2F7/8-occupied promoters (ChIP-seq) represent putative ‘developmental’-associated direct targets. (B) Expression heat map of DEGs in livers or tumors from 12-month-old mice as measured by RNA-seq. DEGs were identified using CuffDiff (≥ 1.5-fold change and FDR < 0.5 between 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ tumor vs. normal control samples). Overlap of DEGs and E2F7/8-occupied promoters represent putative ‘tumor’-associated direct targets. (C) Transcription factor (TF) binding site analysis of putative E2F7/8 targets showing the occurrence and estimated importance of the top 10 TF sites as well as all E2F sites (red). (D) Tag-intensity heat map showing the distribution of tags for all E2F7 and E2F8 promoter peaks identified by ChIP-seq that were associated with DEGs. Peaks were centered on E2F8-specific samples except for peaks that were specific to E2F7. (E) Heat map showing the expression of the 88 developmental-associated E2F7/8 target genes (from A) in normal (Norm) and diseased human patient samples. Cirrhosis (Cir), dysplasia (Dysp), early (E HCC), or advanced HCC (Adv HCC) human livers. (F) Heat map showing the expression of the 69 tumor-associated E2F7/8 target genes (from B) in normal and diseased human patient samples. (G) Kaplan-Meier plots showing % survival of patients that have low (<10%; black line) or high (≥10%; red line) expression of the 88 ‘developmental’-associated target genes. (H) Kaplan-Meier plots showing % survival of patients that have low (<10%; black line) or high (≥10%; red line) expression of the 69 ‘tumor’-associated target genes. HR, hazard ratio (G and H).

Thus, we focused our subsequent analysis on upregulated transcripts. The ‘sequence tag-intensity map’ shown in Figure 8D illustrates the 136 upregulated E2F7 and E2F8 unique and shared targets (67 developmental only, 48 tumor only, and 21 upregulated in both developmental and in tumor data sets). This analysis shows that the majority of target promoters are bound by E2F8, with very few target promoters bound only by E2F7. Gene ontology analysis revealed targets in several cell cycle, DNA damage repair, and checkpoint pathways with functions related to cell cycle, DNA replication, cell survival, cancer, and hepatic system development, function, and disease (Supplemental Figure 5, A and B, and Supplemental Tables 8 and 9).

To determine the relevance of these findings to human HCC, we used the 88 developmental- or 69 tumor-related targets (from Figure 8, A and B, respectively) to query human liver–derived mRNA profiles from normal healthy individuals and patients with cirrhosis, dysplasia, early HCC, or advanced HCC (24). The resulting heat maps show that the majority of shared or E2F8-specific target genes have increased expression in patients with early and advanced HCC (Figure 8, E and F, and Supplemental Tables 10 and 11). Interestingly, the expression of a subset of target genes (derived from the 12-month cohort of mice) was increased in cirrhotic and dysplastic human samples (Figure 8F). Importantly, high expression of developmental-related or tumor-related targets was also evaluated in TCGA data sets and correlated with decreased survival (Figure 8, G and H, and Supplemental Figure 6, A and B), consistent with previous reports documenting a similar association for many of these genes in HCC (Supplemental Table 12). Based on these observations, we suggest that increased E2F transcriptional output in preneoplastic and neoplastic livers of E2F7/8 mutant mice (7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ, 8Δ/Δ, and 8DBD/DBD) is associated with HCC development in humans.

Discussion

Disruption of the CDK/RB/E2F pathway leading to increased E2F transcriptional activity is believed to be a universal requirement for tumor cell proliferation (30). Using a series of E2f7 and E2f8 alleles we show, to our knowledge for the first time, that increased E2F transcriptional output caused by loss of atypical E2F repressors leads to HCC development in mice. Remarkably, loss of tumor suppression early during postnatal liver development, but not later when hepatocytes cease to proliferate (unless injured), was sufficient to predispose to HCC in aging mice. Mechanistic studies employing knockin mice showed that DNA binding activity is required for E2F8’s tumor suppressor function. Genome-wide ChIP and mRNA expression profiling revealed that E2F8 regulates a core set of target genes during early mouse liver development and in liver tumors that are involved in cell cycle, checkpoint regulation, DNA repair, and metabolism. Importantly, these targets were progressively upregulated in early and advanced human HCC. We propose that increased E2F transcriptional output early in postnatal liver development sets up an environment that drives HCC later in life.

Tumor suppressive function of E2F8.

Analysis of TCGA data sets revealed that E2F7 and E2F8 are highly expressed in a number of cancer types. Our findings explain why E2F8 expression appears to be elevated in patients with HCC. E2F8 is under tight transcriptional autoregulation by E2Fs (1, 3, 10). Indeed, we measured strong E2F1 and E2F3A/B occupancy on E2F consensus sites near E2f8’s TSS (Figure 1), which is consistent with peak E2F8 expression levels in late S phase. Thus, like other E2F targets, including the BRCA1, RAD51, and FANCD2 tumor suppressors, E2F8 is highly expressed in proliferating cells of developing and regenerating tissues (3). Not surprisingly, we observed that high E2F8 expression in human liver tumors correlated strongly with expression of the proliferation marker MKI67 and that E2F8 protein in mouse livers exclusively colocalized with KI67 positivity (Figures 1C and 5F). Importantly, the mutant 8DBD protein, despite lacking DNA binding activity, was expressed at similar levels in proliferating hepatocytes of normal and neoplastic livers (Supplemental Figure 3). Thus, we conclude that increased E2F8 expression in cancer, like that of BRCA1 and other tumor suppressors involved in homologous recombination–mediated DNA repair, such as RAD51 and FANCD2, simply reflects the high percentage of proliferating cells present in tumors.

Here we show a specific tumor suppressor role for the atypical E2F8 repressor in vivo. The targeted deletion of E2f8 promoted DEN-induced HCC, and in combination with loss of E2f7, led to spontaneous HCC formation in mice (Figures 1 and 2). Furthermore, the inactivation of E2F8’s DNA binding activity by a 2–amino acid substitution in 8DBD mice was sufficient to promote HCC in vivo (Figure 6). Thus, based on several knockout and knockin mouse models described here, we conclude that E2F8 is a nuclear factor that suppresses the initiation of HCC via a cell-autonomous mechanism involving binding to specific genomic DNA sequences on target promoters. The role of E2F8 in tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis remains to be determined.

Two recent reports suggested that, in contrast to our findings, increased levels of E2F8 in tumor cell lines activate E2F target genes and promote cellular proliferation, whereas knockdown of E2F8 expression retarded cell proliferation (22, 23). The reported decrease in the tumorigenicity of E2F8-knockdown tumor cells may be attributed to increased apoptosis rather than decreased cell proliferation per se, since E2F8 loss has been shown to also sensitize cells to programmed cell death (10). Alternatively, it is entirely possible that E2F8 may have context-dependent functions, protecting against cancer initiation in developing livers (as shown here) but enhancing cancer progression in already transformed cells (as shown by these previous studies). However, the oncogenic properties of E2F8 described by others may be limited to selected cell lines or tissue types. Past studies have shown that overexpression of E2F8 in normal primary (or established) cell lines results in severe growth inhibition (3, 4). Notably, we also observed here that overexpression of wild-type E2F8, but not a DNA binding–defective mutant of E2F8, inhibited the proliferation of a human HCC–derived cell line (HepG2; data not shown). Indeed, our results clearly demonstrate that normal hepatocytes lacking E2F8 proliferate avidly (13, 15). Moreover, 8Δ/Δ mice develop large, highly proliferative, multifocal, and aggressive liver tumors. We suggest that targeting E2F8 as a therapeutic approach in cancer, as proposed recently by others (22, 23), needs further consideration.

Mechanisms of E2F8-mediated tumor suppression.

The observation that either the complete loss of E2F8 expression or the specific inactivation of E2F8’s DNA binding activity leads to HCC strongly suggests that transcriptional deregulation is at the heart of its tumor suppression function. The intersection of chromatin occupancy and expression profiling identified a core set of E2F7/8 target genes (Figure 8) highly enriched for DNA repair or checkpoint activities (Brip1, Chek1, Clspn, Exo1, Fancd2, Rad51, Rad51ap1, Rad54l, Stil, and Timeless), proteins involved in maintaining optimal levels of nucleotide pools (Rrm2), and key components of DNA methylation machineries (Ezh2, Hells, and Uhrf1). While the precise biochemical mechanism underlying the regulation of these targets remains to be determined, we speculate that E2F-mediated activation (in late G1-S) and E2F7/8-mediated repression (in late S-G2) at temporally distinct phases of the cell cycle is critical to coordinate their oscillatory expression and foster the timely progression through the cell cycle. Disruption of coordinated E2F target gene expression by the ablation of E2F8 may lead to increased E2F transcriptional output at inappropriate phases of the cell cycle (10) and hamper the ability of cells to accurately replicate and repair the genome during peak periods of hepatocyte proliferation. Thus, increased genomic instability may be driving tumorigenesis in E2f8-deficient cells.

The work here identifies a critical window of time during early liver development in which control of E2F activity is essential for tumor suppression (Figure 9). While E2Fs are not required for hepatocyte proliferation per se, as our loss-of-function models show, the quality of DNA replication may be compromised when E2F transcriptional output is increased beyond normal physiological levels. Normally, cells with increased DNA damage would be eliminated by programmed cell death; however, hepatocytes lacking E2F7/8 failed to display increased activation of apoptotic programs (Supplemental Figure 5B and data not shown). Thus, we propose that the untimely increase in E2F output during critical periods of hepatocyte proliferation, during development and possibly at times of stress and liver damage, in the absence of apoptosis may lead the accumulation of cells with DNA damage. This interpretation may help explain the evolutionary investment in restricting E2F activity during key phases of the cell cycle via multiple transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms, including silencing by miRs, acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and protein degradation (31). Future studies will be needed to evaluate how E2F protein modifications geared to repress, degrade, or modulate E2F activities impact animal physiology.

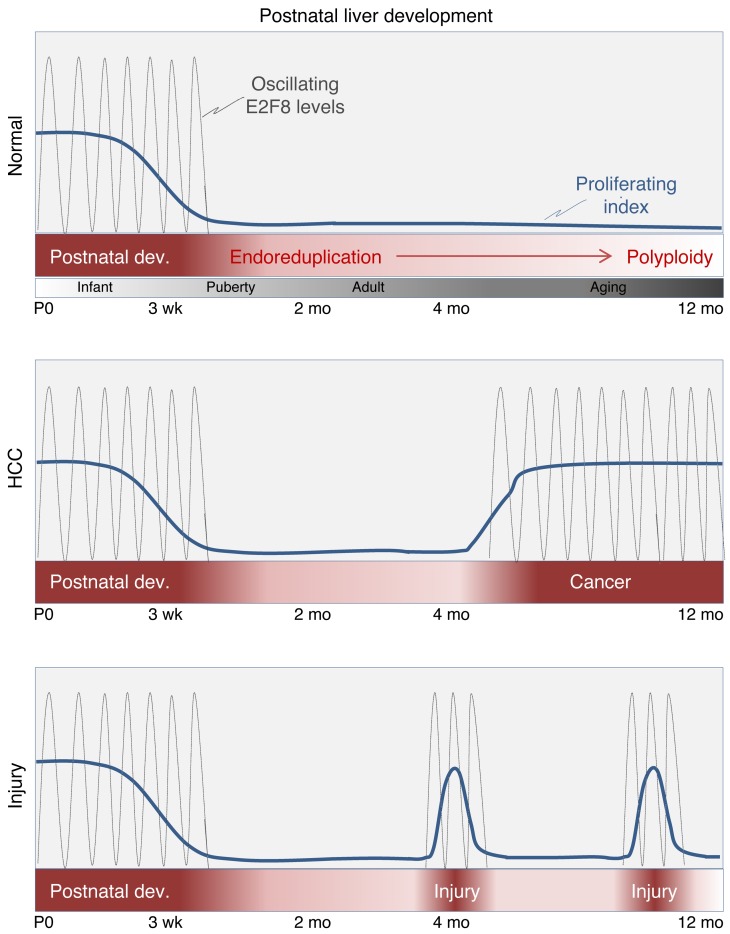

Figure 9. Schematic diagram of hepatocyte proliferation during mouse development, liver injury, and cancer.

Summary diagram illustrating the timing of hepatocyte proliferation and the oscillatory nature of E2F8 protein expression during mouse postnatal liver development, cancer, and liver injury. Mouse hepatocyte proliferation during the first weeks of life is a critical time period when the liver is most susceptible to the initiation of HCC. E2F8 plays a critical role in suppressing HCC during this early developmental stage. We also suggest that E2F8-mediated transcriptional repression in cycling hepatocytes may be critical to suppress carcinogenesis following acute (depicted in the bottom panel) or chronic liver injury.

Why is the developing liver particularly sensitive to increased E2F transcriptional output?

Why immature proliferating hepatocytes may be uniquely sensitive to altered levels of E2F target gene expression is a matter of speculation. Cellular proliferation in a persistently toxic environment is a key feature of developing livers that may explain the cancer susceptibility of mice lacking E2F8. Postnatal livers go through a rapid phase of hepatocyte proliferation immediately following birth, which quickly subsides after 3 weeks of age. Acute liver damage leading to hepatocellular death can also restimulate hepatocyte proliferation in adults in an attempt to compensate for liver-mass loss. Because the liver is the main site for detoxification, a process that exposes hepatocytes to persistent DNA-damaging insults and stimulates repeated rounds of apoptosis and hepatocyte proliferation, the liver may be more sensitive than other organs to increased E2F transcriptional output.

Our current observations have significant implications for understanding development and treatment of HCC in humans. For example, the findings described here raise the possibility that aberrantly high E2F transcriptional output during early liver development in infants and children may alter the genetic and epigenetic integrity of hepatocytes and predispose to HCC later in life. In summary, we identified a novel role for atypical E2Fs in hepatocytes of young mice that is largely dispensable for normal liver function yet critical to prevent HCC later in life.

Methods

Further information can be found in Supplemental Methods.

Database analysis and data mining.

Human HCC gene expression analysis was performed on a public data set (GSE6764; ref. 24) downloaded from the GEO. Raw Affymetrix HGU113plus2 (.CEL) files were analyzed using Flexarray 1.6.1. software (University of Quebec, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Data were normalized using the Just RMA algorithm, and normalized expression values of transcripts were tested for significant differences using Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple tests or Wilcoxon method with Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) correction.

Mouse care and models.

Mice were housed under normal conditions. Alb-Cre, Alb-CreERT2, E2f7fl/fl, and E2f8fl/fl mouse lines were described previously (10, 25, 28). 8DBD mice were generated using standard homologous recombination techniques to introduce the targeted allele into mouse ES cells and generate chimeric mice by the Genetically Engineered Mouse Modeling Core Shared Resources at Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (OSUCCC). Alb-Cre E2f7fl E2F8fl mice were fifth-generation FVB/NT. All other lines were on a mixed background (FVB/NT, 129v/Sv, C57BL/6NT). Genotyping was performed on tail or liver DNA using standard PCR techniques; primer sets used are listed in Supplemental Table 13. Two-third partial hepatectomies were performed as described in ref. 32 wherein the left lateral and median lobes are removed. Mice were harvested 32 hours after partial hepatectomy. Mice that were in distress or had sustained injuries were evaluated by veterinary staff. Removal criteria included presence of non-healing wounds, weight loss, dehydration, or overall failure to thrive. Dissected livers were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C for further analysis or fixed in 10% formalin (Fisher Scientific) for histological analyses.

DEN and tamoxifen treatment of mice.

Mice received DEN (Sigma-Aldrich) by intraperitoneal injection (20 mg/kg body mass) at 20 days of age (27, 33). For inducible deletion of E2f8 using Alb-CreERT2, mice were fed tamoxifen chow (Harlan Laboratories; Sigma-Aldrich) ad libitum for 7 days starting at either 1 week (administered to dam) or 4 weeks of age. Mice were fed normal chow at all other times (13).

Histology.

Formalin-fixed mouse tissue was processed and stained with H&E using standard protocols. For immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence, slides were processed as previously described (15) or stained using a BOND RX autostainer (Leica) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Primary antibodies against KI-67 (Biogenex MU297-UC or Abcam 16667) or MYC-Tag (Abcam 9132 or Cell Signaling Technology 2278) were used. DNA replication was detected by injecting mice with 5 mg/kg body weight of EdU (Life Technologies; C10337) dissolved in sterile PBS 30 minutes prior to harvesting. EdU incorporation was visualized using a Click-iT EdU AlexaFluor 594 Imaging Kit (Life Technologies). HCC was determined by pathologists using standard histopathological analysis based on cellular morphology (34).

qPCR.

Total RNA was isolated and DNase treated using the QIAGEN RNeasy Kit. cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers (Fermentas). qPCR was performed on a Bio-Rad MyiQ Cycler using SYBRgreen Supermix (Bio-Rad). Reactions were normalized to Gapdh expression using the ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences for the indicated genes are included in Supplemental Table 14.

Southern blotting for 8DBD.

Mouse ES cells transfected with the 8DBD targeting vector and then screened for correct homologous recombination using Southern blotting. Genomic DNA from ES cells was digested with Sca1 and probed with a labeled fragment binding 5′ to the recombined E2f8 locus, resulting in a 6.4-kb wild-type band and an 8-kb band if recombination occurred.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Nuclei suspensions were obtained from frozen liver tissue as previously described (35). Total DNA content of a minimum of 40,000 nuclei per liver sample was analyzed by the OSUCCC Analytical Cytometry Shared Resource using an LSR II (BD Biosciences). Cell cycle profiles were generated using FlowJo (Tree Star).

Cell culture and ChIP-qPCR.

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from day 13.5 embryos and immortalized using the 3T3 method (36). MEFs, HepG2 (ATCC), and HeLa cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. THLE-2 cells (ATCC) were cultured in modified bronchial epithelial growth media (BEGM Bullet Kit: CC3170, Lonza, without gentamycin/amphotericin and epinephrine, but supplemented with 5 ng/ml EGF, 70 ng/ml phosphoethanolamine, and 10% FBS. E2F1, E2F3A, and E2F3B proteins were overexpressed in MEFs using the pBABE-hygro retroviral system. MYC-8wt and MYC-8DBD were subcloned into the pLenti expression plasmid and overexpressed in HepG2 cells using a lentiviral system. ChIP-qPCR for MYC-8wt and MYC-8DBD (Abcam, 9132) and endogenous E2F7 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, H-300), and E2F8 (Abcam, 109596) in THLE-2 were performed as previously described (13). Endogenous E2F7 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, H-300) and E2F8 (Abcam 109596) in HepG2 cells were performed as previously described in ref. 29 using a double-IP protocol. Primer sequences are included in Supplemental Table 15.

ChIP-seq.

E2F1, E2F3A, and E2F3B ChIPs were performed in MEFs stably overexpressing the proteins and in E2f1–/– and E2f3–/– MEFs. α-E2F1 (clone c20), α-E2F3 (clone C18), or normal rabbit IgG (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used to pull down chromatin. E2F- ChIP DNA was processed to generate libraries using a TruSeq ChIP DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina). Library quality was confirmed using a High Sensitivity DNA assay (Agilent) and then sequenced by the OSUCCC Genomics Shared Resource with a HiSeq 2000 (Illumina). ChIP-seq reads were mapped against the reference genome mm9 using Bowtie2 (37). Peaks were called used Macs1.4 (38) with defaults to gauge peaks. Peaks from the E2f1–/– MEFs were subtracted from the E2F1 ChIP, while E2f3–/– peaks were subtracted from the E2F3A and E2F3B ChIPs.

E2F8 ChIP was performed on endogenous protein in HeLa cells using α-E2F8 (Abcam, ab109596) as previously described for E2F7 (29). The newly generated E2F8 ChIP-seq reads, and the original E2F7 ChIP-seq reads, were mapped against the reference genome (hg19 assembly, NCBI37) using BWA package (-c, –l 25, -k 2, -n 10; ref. 39). Multiple reads mapping to the same location and strand were collapsed to a single read and only uniquely placed reads were used for peak calling using MACS2 (v2.0.10). Peaks were categorized into 5 regions (Promoter: –5 kb to +2 kb from TSS; Enhancer: –50 kb to –5 kb from TSS; Gene Body: +2 kb from TSS to transcription end site [TES]; 3 prime: TES to +30 Mb from TES; 5 prime: –50 kb to –50 Mb from TES). Motif finding was performed using the HOMER motif-finding tool (Salk Institute). IPA (QIAGEN) was used for functional analysis of genes. Reads for individual genes were visualized using the Integrative Genome Viewer (http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv/home).

RNA sequencing.

Total RNA was isolated from livers using the RNeasy Kit (QIAGEN). mRNA was isolated using a Poly(A)Purist MAG Kit (Life Technologies, AM 1922) and additionally purified with an mRNA-ONLY Eukaryotic mRNA Isolation Kit (Epicentre). Transcriptome libraries were then constructed using an Applied Biosystems SOLiD Total RNA-seq Kit (Life Technologies). Library cDNA was amplified, barcoded, and sequenced using a 5500 W Series Genetic Analyzer (Fisher Scientific) to produce 40-bp-long reads. Sequencing reads were mapped against the reference genome (mm9, NCBI37) using BWA (-c –l 25 –k 2 –n 10) software. CuffDiff (v2.2.1; ref. 40) was used to call differentially expressed genes with a fold change between control and 7Δ/Δ8Δ/Δ tumor samples of at least 1.5 and a cutoff of FDR less than 0.5. Heat maps were generated using R (www.r-project.org).

Data mining, heat maps, and HCC patient survival analysis.

E2f7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ 4-week-old liver data sets were downloaded from Array Express (E-MEXP-3384; ref. 15). Upregulated transcripts (P ≤ 0.05) with a greater than or equal to 1.5-fold increase of expression in 7Δ/Δ 8Δ/Δ livers compared to control livers were used for further analysis. The human mRNA expression data sets from normal and diseased liver tissues were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE6764; ref. 22). Data were processed using Expression and Transcriptome Analysis Consoles (Affymetrix). Expression heat maps were generated using R and ordered by the highest median expression in the following order: advanced HCC, early HCC, dysplasia, cirrhotic, and control. Distant regulatory elements (DiRE) analysis was conducted using the DiRE website (http://dire.dcode.org; ref. 41) searching 3′ evolutionary conserved regions (ECRs) and promoter ECRs for genes on the mouse (mm9) genome. Kaplan-Meier plots showing HCC patient survival were produced by R package survplot (ref. 42; http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/~eklund/survplot/). Patient data from the Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) project with RNA-seq v2 were downloaded from cbioportal (http://www.cbioportal.org/). Patients with upregulated expression (Z score > 2) of at least 10% E2F7/8 target genes in patient tumor samples were grouped and compared to patients with less than 10% of E2F7/8 target genes being upregulated; a log-rank test was performed to show significance between different patient groups.

Data deposition.

All data were deposited in the GEO with the following accession numbers: E2F1, E2F3A, and E2F3B ChIP-seq (GSE71383), E2F7 and E2F8 ChIP-seq (GSE32673), and RNA sequencing data (GSE71574).

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed after consultation with the Ohio State University Center for Biostatistics using Sigmaplot (Systat Software Inc.) or JMP (SAS institute) software. Values were found to be significant if P was less than or equal to 0.05. Individual P values and tests used are described in the figure legends. Briefly, 2-tailed Student’s t tests were used for comparisons between 2 groups. When more than 2 groups were compared, Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple tests were used. Fisher’s exact tests with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple tests were used to analyze categorical data. For gene ontology analysis, a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P value was calculated by the IPA software. Significance for ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data was calculated by the analysis software as explained above. Significant changes in gene expression between control and diseased human liver samples were determined by the Wilcoxon method with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Log-rank tests were used to determine significant changes in patient survival depicted in the Kaplan-Meier plots.

Study approval.

Mouse protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at the Ohio State University or Utrecht University.

Author contributions

LNK, JBR, HC, SKP, BW, JTH, SB, AdB, and GL designed the experiments. All authors performed the experiments and collected and analyzed data. GL and AdB supervised the studies. LNK and GL wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Bice and D. Bryant for assistance with histology and Dana LeMoine for assistance with the partial hepatectomies. We also thank J. McElroy for suggestions in the statistical analysis of data and B. Bolon for assistance with assessment of placental pathology. This work was supported by the OSUCCC Genetically Engineered Mouse Modeling, Comparative Pathology and Mouse Phenotyping, Genomics and Analytical Cytometry Core Shared Resources and the Dutch Molecular Pathology Center at Utrecht University. We are thankful to Mike Ostrowski, Denis Guttridge, Lawrence Kirschner, and Christin Burd for critical suggestions. This work was funded by NIH grants to G. Leone (R01CA121275 and CA097189), NIH grant to J.M. Pipas (R01CA098956) and by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (UU 2013-5777) to B. Westendorp and A. de Bruin. L.N. Kent, J.T. Huntington, and S. Bae were recipients of an NCI T32 in “Cancer Genetics”. C. Koivisto was a recipient of an NCI T32 in “Mouse Models of Human Disease”. C.K. Martin and A. Perez-Castro were recipients of Pelotonia Postdoctoral Fellowships; C. Koivisto and H. Chen were recipients of Pelotonia Graduate Fellowships; and J.M. Clouse and V. Chokshi were recipients of Pelotonia Undergraduate Fellowships.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Reference information:J Clin Invest. 2016;126(8):2955–2969. doi:10.1172/JCI85506.

Contributor Information

Bart Westendorp, Email: B.Westendorp@uu.nl.

Hui-Zi Chen, Email: Hui-Zi.Chen@osumc.edu.

Xing Tang, Email: Xing.Tang@osumc.edu.

Sooin Bae, Email: SooIn.Bae@osumc.edu.

Arunima Srivastava, Email: arunima2@vt.edu.

Shantibhusan Senapati, Email: drsantibhusan@yahoo.com.

Christopher Koivisto, Email: christopher.koivisto@osumc.edu.

Veda Chokshi, Email: vedachokshi@gmail.com.

Neelam Shinde, Email: Neelam.Shinde@osumc.edu.

Raleigh Kladney, Email: Raleigh.Kladney@osumc.edu.

Daokun Sun, Email: Daokun.Sun@osumc.edu.

Antonio Perez-Castro, Email: Antonio.Perez-Castro@osumc.edu.

Sathidpak Nantasanti, Email: S.Nantasanti@uu.nl.

Michal Mokry, Email: m.mokry@umcutrecht.nl.

Kun Huang, Email: Kun.Huang@osumc.edu.

Raghu Machiraju, Email: machiraju.1@osu.edu.

Soledad Fernandez, Email: Soledad.Fernandez@osumc.edu.

Vincenzo Coppola, Email: vincenzo.coppola@osumc.edu.

Alain de Bruin, Email: a.debruin@uu.nl.

Gustavo Leone, Email: gustavo.leone@osumc.edu.

References

- 1.de Bruin A, Maiti B, Jakoi L, Timmers C, Buerki R, Leone G. Identification and characterization of E2F7, a novel mammalian E2F family member capable of blocking cellular proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(43):42041–42049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Stefano L, Jensen MR, Helin K. E2F7, a novel E2F featuring DP-independent repression of a subset of E2F-regulated genes. EMBO J. 2003;22(23):6289–6298. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maiti B, et al. Cloning and characterization of mouse E2F8, a novel mammalian E2F family member capable of blocking cellular proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(18):18211–18220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logan N, et al. E2F-8: an E2F family member with a similar organization of DNA-binding domains to E2F-7. Oncogene. 2005;24(31):5000–5004. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iaquinta PJ, Lees JA. Life and death decisions by the E2F transcription factors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19(6):649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lammens T, Li J, Leone G, De Veylder L. Atypical E2Fs: new players in the E2F transcription factor family. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(3):111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen HZ, Tsai SY, Leone G. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(11):785–797. doi: 10.1038/nrc2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frolov MV, et al. Functional antagonism between E2F family members. Genes Dev. 2001;15(16):2146–2160. doi: 10.1101/gad.903901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giangrande PH, et al. A role for E2F6 in distinguishing G1/S- and G2/M-specific transcription. Genes Dev. 2004;18(23):2941–2951. doi: 10.1101/gad.1239304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, et al. Synergistic function of E2F7 and E2F8 is essential for cell survival and embryonic development. Dev Cell. 2008;14(1):62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, et al. The E2F1-3 transcription factors are essential for cellular proliferation. Nature. 2001;414(6862):457–462. doi: 10.1038/35106593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenzel PL, et al. Cell proliferation in the absence of E2F1-3. Dev Biol. 2011;351(1):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen HZ, et al. Canonical and atypical E2Fs regulate the mammalian endocycle. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(11):1192–1202. doi: 10.1038/ncb2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouseph MM, et al. Atypical E2F repressors and activators coordinate placental development. Dev Cell. 2012;22(4):849–862. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandit SK, et al. E2F8 is essential for polyploidization in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(11):1181–1191. doi: 10.1038/ncb2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aksoy O, et al. The atypical E2F family member E2F7 couples the p53 and RB pathways during cellular senescence. Genes Dev. 2012;26(14):1546–1557. doi: 10.1101/gad.196238.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagemann IS, Narzinski KD, Baranski TJ. E2F8 is a nonreceptor activator of heterotrimeric G proteins. J Mol Signal. 2007;2: doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vooijs M, Berns A. Developmental defects and tumor predisposition in Rb mutant mice. Oncogene. 1999;18(38):5293–5303. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laurent-Puig P, Zucman-Rossi J. Genetics of hepatocellular tumors. Oncogene. 2006;25(27):3778–3786. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferlay J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng Q, et al. E2F8 contributes to human hepatocellular carcinoma via regulating cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):782–791. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park SA, Platt J, Lee JW, López-Giráldez F, Herbst RS, Koo JS. E2F8 as a novel therapeutic target for lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(9): doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wurmbach E, et al. Genome-wide molecular profiles of HCV-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;45(4):938–947. doi: 10.1002/hep.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Postic C, Magnuson MA. DNA excision in liver by an albumin-Cre transgene occurs progressively with age. Genesis. 2000;26(2):149–150. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1526-968X(200002)26:2<149::AID-GENE16>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayhew CN, et al. RB loss abrogates cell cycle control and genome integrity to promote liver tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(3):976–984. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vesselinovitch SD. Certain aspects of hepatocarcinogenesis in the infant mouse model. Toxicol Pathol. 1987;15(2):221–228. doi: 10.1177/019262338701500216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuler M, Dierich A, Chambon P, Metzger D. Efficient temporally controlled targeted somatic mutagenesis in hepatocytes of the mouse. Genesis. 2004;39(3):167–172. doi: 10.1002/gene.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westendorp B, Mokry M, Groot Koerkamp MJ, Holstege FC, Cuppen E, de Bruin A. E2F7 represses a network of oscillating cell cycle genes to control S-phase progression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(8):3511–3523. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(3):153–166. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munro S, Carr SM, La Thangue NB. Diversity within the pRb pathway: is there a code of conduct? Oncogene. 2012;31(40):4343–4352. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell C, Willenbring H. A reproducible and well-tolerated method for 2/3 partial hepatectomy in mice. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(7):1167–1170. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vesselinovitch SD. Infant mouse as a sensitive bioassay system for carcinogenicity of N-nitroso compounds. IARC Sci Publ. 1980;(31):645–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoolen B, et al. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse hepatobiliary system. Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38(7 ):5S–81S. doi: 10.1177/0192623310386499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayhew CN, et al. Liver-specific pRB loss results in ectopic cell cycle entry and aberrant ploidy. Cancer Res. 2005;65(11):4568–4577. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J. Preparation, culture, and immortalization of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2005;Chapter 28: doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2801s70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9(9): doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trapnell C, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Goff L, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(1):46–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gotea V, Ovcharenko I. DiRE: identifying distant regulatory elements of co-expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W133–W139. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Eklund A. Survplot. http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/~eklund/survplot/ R Web site. Updated April 4, 2012. Accessed June 15, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.