Abstract

Phage-display technology facilitates rapid selection of antigen-specific single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibodies from large recombinant libraries. ScFv antibodies, composed of a VH and VL domain, are readily engineered into multimeric formats for the development of diagnostics and targeted therapies. However, the recombinant nature of the selection strategy can result in VH and VL domains with sub-optimal biophysical properties, such as reduced thermodynamic stability and enhanced aggregation propensity, which lead to poor production and limited application. We found that the C10 anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) scFv, and its affinity mutant, P2224, exhibit weak production from E. coli. Interestingly, these scFv contain a fusion of lambda3 and lambda1 V-region (LV3 and LV1) genes, most likely the result of a PCR aberration during library construction. To enhance the biophysical properties of these scFvs, we utilized a structure-based approach to replace and redesign the pre-existing framework of the VL domain to one that best pairs with the existing VH. We describe a method to exchange lambda sequences with a more stable kappa3 framework (KV3) within the VL domain that incorporates the original lambda DE-loop. The resulting scFvs, C10KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3_LV1DE, are more thermodynamically stable and easier to produce from bacterial culture. Additionally, C10KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3_LV1DE retain binding affinity to EGFR, suggesting that such a dramatic framework swap does not significantly affect scFv binding. We provide here a novel strategy for redesigning the light chain of problematic scFvs to enhance their stability and therapeutic applicability.

Keywords: antibody engineering, EGFR, scFv antibody, stability engineering, thermostability

Abbreviations

- scFv

single-chain variable fragment

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- VH

variable heavy

- VL

variable light

- CDR

complementarity-determining region

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

Introduction

Antibody therapeutics represent a growing class of molecules entering clinical trials.1 Single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibodies are composed of the variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) domains of an immunoglobulin (Ig) tethered by a peptide linker.2 scFvs are highly versatile in their use in basic research, diagnostics, and therapy, and they are easily engineered into higher order formats such as bispecific (including bispecific T-cell engagers) or trispecific antibodies, chimeric antigen receptors, or IgG.3-6 Identification of target-specific scFvs by various display technologies that utilize a genetic library of VH and VL gene segments is rapid and cost-efficient in comparison to conventional immunization-based strategies.7 While these antibodies are highly target specific, they are often limited in their stability and aggregation propensity, which negatively affect expression, purification, concentration, immunogenicity, and function.8-12 This is due in part to the lack of quality control mechanisms that are usually provided by an antibody-producing B cell, and results in selection of scFvs with suboptimal structural stability.13 The impaired stability may be the result of a lack of stabilizing Fab constant regions, incompatible VH/VL pairings, as well as PCR-induced aberrations such as missense mutations and gene fusions. Although the structural integrity of these antibodies may be sufficient for their use in basic research, their biophysical properties must be optimized if they are to be incorporated into clinical diagnostics and therapeutic agents.

The ErbB tyrosine kinases are often over-expressed and the key drivers of tumor promotion in multiple cancer types, particularly head and neck, lung, breast, and gastric cancers.14 This makes ErbB members particularly ideal targets for therapeutic antibody blockade. For example, the monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab block ErbB1/epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling and are approved for use in head and neck and colorectal cancer,15-17 while trastuzumab and pertuzumab bind to domains IV and II of ErbB2, respectively, to block ErbB2 activity and are approved for breast and gastric cancers.18

The anti-EGFR scFv, C10, was previously identified from a phage antibody library and selected for its ability to promote EGFR internalization, a valuable feature that can be utilized for antibody drug delivery.19 However, C10 scFvs and one of its affinity-matured variants, P2224, tend to aggregate.20 Because of their favorable biological properties, it would be desirable to engineer more stable variants of these antibodies prior to further stages of drug development. We examined the C10 framework sequence and determined that the VL domain is likely to be a fusion between λ3 (LV3) and λ1 (LV1) V-region genes, and that the sequence is probably a byproduct of PCR amplification during library construction. Many affinity-matured derivatives of C10 have been generated and all contain this hybrid light chain. Based on the non-native nature of this framework sequence, we propose that the VL λ3-λ1 fused framework negatively affects the overall biophysical characteristics of the C10 scFv and its derivatives. Additionally, we anticipate that the VL λ3-λ1 framework will contribute to suboptimal behavior when engineered into higher order antibody formats.

The mechanisms controlling antibody production, thermostability, and aggregation resistance are not completely understood and various methods have been employed to enhance the biophysical properties of antibodies, including stability engineering of the hydrophobic core, surface-exposed residues, and the VH:VL domain interface.1,8,21-23 Here, we describe a structure-based redesign strategy in combination with our previously described complementarity-determining region (CDR) clustering scheme24 to graft the VL CDRs of C10 and P2224 onto a more stable VL κ3 (KV3) framework. This is the first demonstration that a structure-guided redesign involving a λ to κ switch successfully improves the stability of an scFv while maintaining comparable binding affinity.

Results

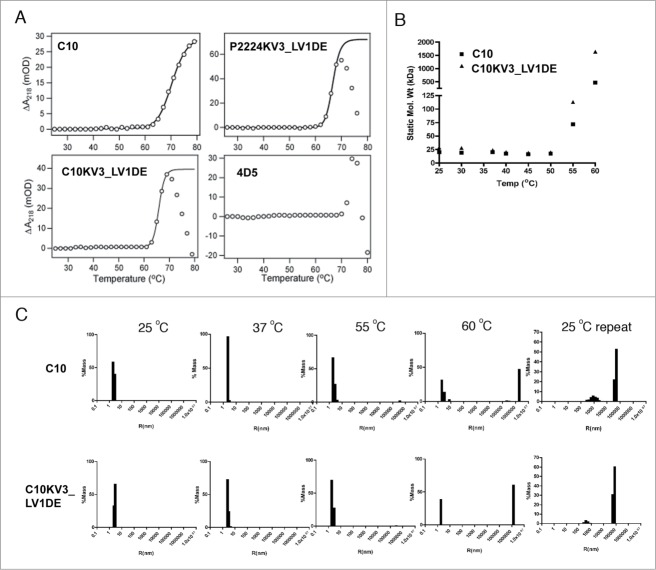

Selection of the Vκ3 framework, C10 homology modeling, and redesign

One potential indicator of scFv stability and propensity to aggregate is total protein yields during production.25 Under the production strategies employed in these studies, increased expression temperatures appeared to negatively affect yields of the parental scFv proteins. Yields of 2.5 mg/L (range: 2.3 – 2.6) and 0.9 mg/L (range: 0.4 – 1.5) of purified C10 scFv protein were obtained when expressions were carried out at 25 and 30 °C, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). Despite differing by only a single framework residue and 3 residues in the VH CDRs, the yields of the affinity matured P2224 were dramatically lower than those obtained with C10 at both temperatures; yields of 0.6 mg/L (range: 0.3 – 1.2) and 0.12 mg/L (range: 0.07 – 0.18) of culture were obtained at 25 and 30 °C, respectively (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). This suggested that the P2224 scFv was, like C10, unstable at higher temperatures and that the affinity maturation process further destabilized P2224 relative to the parental molecule.

Figure 1.

(A-B) Elution of indicated scFv with increasing imidazole from a HisTrap column after loading with 500 ml (A) or 250 ml (B) culture supernatant from TG1 cells induced to produce protein at 30°C (left panel). SDS-page gel of isolated scFv stained with SimplyBlue (right panel). (C) Fold induction of C10 or C10KV3_LV1DE from TG1 cells at 25 or 30 °C relative to C10 production. (D) Fold induction of P2224 or P2224KV3_LV1DE from TG1 cells at 25 or 30 °C relative to P2224 production. (E) Fold induction of C10KV3 or C10KV3_LV1DE. Bars represent the range of fold production from 2 independent experiments.

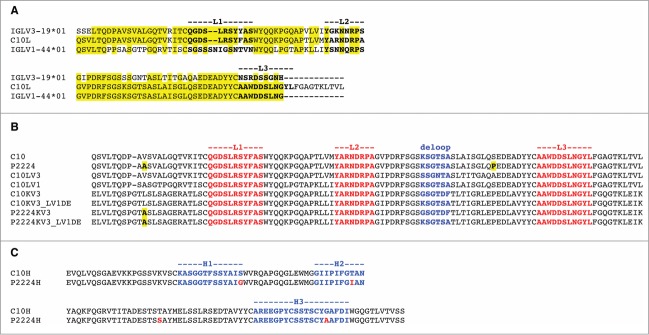

To determine what elements in the protein sequence and structure might lead to low stability, we compared the protein sequences of the parental C10 light and heavy chains to human germline V-region sequences provided by IMGT.26 The C10 heavy chain sequence (through the beginning of CDR H3) is 99% identical to the human IGHV1–69*01 amino acid sequence. The C10 light chain sequence showed the highest sequence identity (87%) to λ light chain V-region gene IGLV3–19*01 through the beginning of CDR L2 but only 66% after L2 (Fig. 2A). By contrast, C10L was 51% identical to λ light chain V-region gene IGLV1–44*01 through the beginning of L2 but 100% identical after L2, including the first 9 residues of L3. The DNA sequences also showed high similarity to IGLV3–19*01 through CDR L2 and high similarity to IGLV1–44*01 after L2. We concluded that the VL sequences of C10 and its derivatives are likely to contain a fusion product of Vλ3 (IGLV3-19*01) and Vλ1 (IGLV1-44*01) V-region genes. Since this fusion is not typically found in nature and Vλ3 (IGLV3-19*01) and Vλ1 (IGLV1-44*01) V-region genes. Since this fusion is not typically found in nature and Vλ domains tend to confer lower production yields from bacteria and a greater propensity to aggregate,27 it was likely that the hybrid Vλ sequence was the source of poor production.

Figure 2.

(A) Alignment of C10 light chain (C10L) with human IGLV1–44*01 and IGLV3-19*01 germline amino acid sequences. Residues in IGLV1–44*01 and IGLV3–19*01 identical with those in C10L are highlighted in yellow. The three CDRs are marked (definitions according to North et al.). (B) Alignment of light chains: C10, P2224, C10LV3, C10LV1, C10KV3, C10KV3_LV1DE, P2224KV3, and P2224KV3_LV1DE, C10KV3 and (C) alignment of heavy chains, C10H and P2224H.

To improve the production of C10 and P2224, we decided to swap the VL framework of C10 with a more stable VL framework that would also likely pair well with the IGHV1–69 domain of C10. Ewert et al. found that Vκ3 frameworks are the most stable VL domains when studied in isolation from the VH domain.27 They also found that the combination of IGHV1–69 (their VH1a) with IGKV3 (their Vκ3) produced the highest soluble yields of all the combinations they tested, except for the VH1b/Vκ3 combination (closest to IMGT IGHV1–2/IGKV3D-7), which was slightly higher.27 More recently, Tiller et al. have determined the usage frequency of each germline V region in the human antibody repertoire as well as the pairing frequency of VH and VL domains.28 Of all VL domains, they found IGKV3–20 to be the most common, followed by IGKV1–39. For pairing with IGHV1–69, these 2 domains were the most common and approximately equal (12 and 14 cases, respectively) followed by IGKV3–11 (8 cases), IGKV3–15 (7 cases), and IGKV1–5 (5 cases). They also find the highest expression levels with IGHV1–69 to be IGKV1–5, IGKV3–11, IGKV3–20, and IGKV3–15, all roughly equal. We recently assigned germline V regions to all structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB)29 and analyzed the pairing frequency of human VH and VL domains in antibodies of known structure. In a non-redundant set of antibodies, the most common pairing with IGHV1–69 was IGKV3–20 (7 cases), followed by IGKV1–39 (4 cases) and IGKV1–33 (4 cases). While the counts in these studies are not high, we chose the IGKV3–20 framework as a promising lead for producing a stable antibody with the IGHV1–69 domain of C10.

We chose the antibody X5 from PDB entry 1RHH30 as a template for grafting the C10 CDRs, since it has been well studied30,31 and is the closest IGHV1–69 domain to C10 VH that is also bound to an IGKV3–20 domain. To guide our design process, we constructed homology models of C10 and C10 with an IGKV3–20 framework based on the sequence of the light chain of PDB entry 1RHH by grafting CDRs from templates with similar sequences onto suitable frameworks. The side chain conformations for the new sequences were optimized with the program SCWRL4 (see Materials and methods). A sequence alignment of C10 and C10KV3 is shown in Figure 2B. Parent and target structures were inspected visually for inconsistencies caused by the CDR grafts.

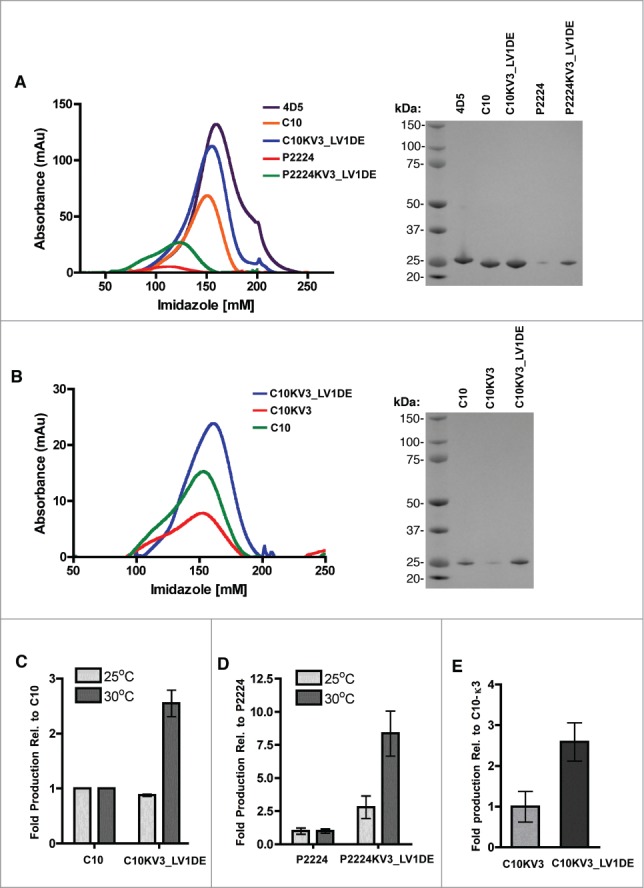

One noticeable problem from this structural inspection was a clash between the grafted λ3 CDR-L1 and the acceptor framework's κ3-typical d-e loop. The d-e loop (nomenclature according to ref.32) is a framework loop of the FR3 region (residues 66–71 in Chothia numbering) between CDR2 and CDR3 that makes extensive contacts with CDR1. A close-up of the L1 and d-e loops of the unrefined models of C10 and C10KV3 is shown in Figure 3A. The d-e loop sequence motifs in κ and λ germline sequences are distinct, i.e., G[SPY]GT[DE][FY] and [KRN]SG[NTK][ST]A, respectively. In C10, the sequence of the d-e loop is KSGTSA, while in C10KV3 sequence is GSGTDF. In Figure 3A, the d-e loop of the C10KV3 model (blue) exhibits a large deviation from the C10 model (magenta).

Figure 3.

(A) Superposition of models of C10 (magenta) and C10KV3 (blue). The d-e loop side chains of K66 of C10 and F71 of C10KV3 are shown in sticks. (B) The L1–11 and d-e loops of 81 human κ and 32 human λ structures. The κ loops are in light-blue (L1) and dark blue (d-e loop) and the λ loops are in magenta (L1) and dark purple (d-e loop). (C) Hydrophobic cluster in κ3 antibodies, including F/Y71 (blue) and residues 6 (green) and 10 (orange) of the length 11 L1 loops. (D) Hydrophobic cluster in λ3 antibodies, including the hydrophobic portion of K/N/I 66 (magenta), A71 (dark purple), and residues 5 (green) and 10 (orange) of the length 11 loops.

We investigated if this clash was an artifact of the particular combination of CDR donor and acceptor framework structures or if this feature is more generally true for λ3-to-κ3 grafts. We performed a structure alignment with the program THESEUS33 of a non-redundant set of 113 κ3 and λ3 light chain variable domains (each with a different CDR L1 sequence of length 11), and the result is shown in Figure 3B When CDR L1 is 11 residues in length, there are 3 predominant clusters.29 The 2 largest are L1–11–1 and L1–11–2, consisting entirely of L1 CDRs from κ light chains.24 In both of these clusters, residue 71 of the d-e loop participates in a hydrophobic cluster of amino acid side chains consisting of residue 71 (Phe or Tyr) and residues 6 and 10 of the 11-amino acid L1 loop (usually Leu, Ile, and Val). This cluster of interactions is shown in Figure 3C. Residue 71 is Phe in nearly all L1–11–1 CDR structures and Tyr in L1–11–2 structures (almost all of which are mouse frameworks29). The Tyr hydroxyl makes a hydrogen bond with the backbone of residue 7 of the L1 loop, flipping the conformation of residues 7 and 8.

By contrast, λ light chains with 11-amino acid L1 CDRs exist almost entirely in cluster L1–11–3, with a distinct sequence pattern compared to L1–11–1 and L1–11–2 CDRs in κ antibodies. In the PDB, these antibodies are all human IGLV3 (except for one hamster structure and one macaque structure) since other λ germlines (including human IGLV1) do not have L1 CDRs of length 11. The structures of L1–11–3 CDRs are quite different from L1–11–1 and L1–11–2, with residues 5 and 10 of the CDR pointing toward each other, inwards into the VL domain core, and participating in a hydrophobic cluster with the side chain of A71 and in some cases the hydrophobic portions of K/N/I66 of the d-e loop, as shown in Figure 3D. Computationally mutating A71 to Phe in λ antibodies results in severe steric conflicts with residues 5 and 10 of the L1 CDR (not shown), indicating that the conformation of L1–11–3 is not consistent with a Phe residue at position 71 in the d-e loop.

G66 of the d-e loop is completely conserved in human κ germline sequences, while this position is never Gly in human λ germline sequences. Glycine is able to access backbone conformations that residues with side chains are not able to achieve, in particular those with backbone dihedral f > 0°.34 G66 has ϕ > 0° (mean = 117°, std = 15°) in 792 or 99% of 807 (redundant) human κ domains in the PDB. As shown in Figures 3A and B, G66 allows the d-e loop to bend inward, toward the L1 loop. In contrast, the λ-typical K/R/N/I side chains at position 66 result in a β-sheet like backbone conformation with f < 0° (mean −141°; std = 21°) in 464 or 99% of 468 human λ domains in the PDB. Visual inspection of λ3 d-e loops shows that the Lys, Arg, and Asn side chains at position 66 usually hydrogen bond to the backbone carbonyls of residues 5 and/or 8 of the L1 loop, stabilizing the λ-like L1–11–3 conformation. The change in backbone conformation at position 66 is evident in Figures 3A and 3B.

It is certainly possible that small adjustments in backbone and side-chain conformations could remove the clash shown in Figure 3A, resulting in a stable C10KV3 molecule. To investigate this, we utilized RosettaAntibody to build models of C10, C10KV3, and C10KV3 with a d-e loop with C10's λ1 sequence (C10KV3_LV1DE). For comparison, we also built models of all-λ3 and all-λ1 variants of C10 (C10LV3 and C10LV1). The sequences of these constructs are given in Figure 2B.The initial model of C10KV3_LV1DE from RosettaAntibody utilized a κ-like structure of the d-e loop, because the program used a κ3 template. To produce a better model, we grafted a d-e loop with the sequence KSGTSA (as in C10) from the IGLV1–44*01 antibody in PDB entry 4GXV35 into the RosettaAntibody model of C10KV3_LV1DE.

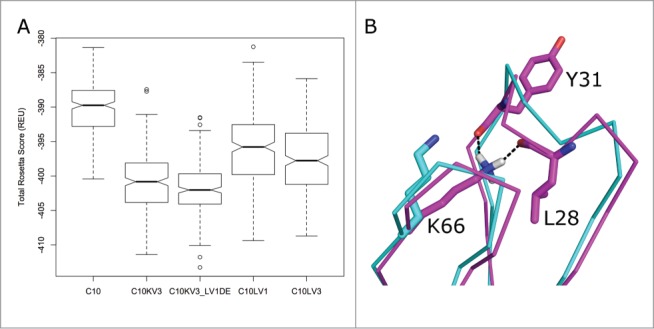

To obtain structural scores that might be correlated roughly with stability, we applied a refinement strategy in the program Rosetta that allows for changes in bond lengths and bond angles (“Cartesian minimization”)36 during extensive repacking of side chains with our backbone-dependent rotamer library37 and local optimization of both side-chain and main-chain dihedral angles. Each run consists of optimization moves in a random order so each resulting model (or decoy) is different. Starting from the RosettaAntibody models (including the d-e loop grafted C10KV3_LV1DE), we generated 250 decoys for each target with the Cartesian minimization protocol. A box and whiskers plot of these scores is shown in Figure 4A, demonstrating that the distribution of scores for C10KV3_LV1DE is a little lower than C10KV3, and that the κ3 constructs are predicted to be more stable than the λ1 and λ3 variants and the original C10. Notably, the refinement of C10KV3_LV1DE moved K66 of the grafted d-e loop into a position with hydrogen bonds to the backbone carbonyl oxygens of residues 5 and 8 of CDR L1, shown in Figure 4B. Consistent with the Rosetta results, we chose to construct C10KV3_LV1DE and C10KV3 as well as the similar variants of the affinity-matured antibody P2224, i.e., P2224KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3.

Figure 4.

(A) Box-and-whiskers plot of the distributions of Rosetta scores for 250 models (decoys) of refined structures of potential C10 antibody constructs derived by running the dual-space relax protocol of the program Rosetta to models built with RosettaAntibody. The box covers the range from the first (Q1) to the third quartiles (Q3) of the data, and the horizontal line is the median. The whiskers are at Q3+1.5*IQR and Q1–1.5*IQR, where IQR is the interquartile range (Q3-Q1). Outliers beyond the whiskers are marked. (B) Refinement of C10KV3_LV1DE from its initial model (cyan) to a structure with the lowest Rosetta score, which forms a hydrogen bond of the side chain of Lys66 to the backbone carbonyls of the 5th and 8th residues of the CDR L1. This is a common hydrogen bond in λ antibodies when residue 66 is Asn or Lys.

The redesigned VL CDR framework confers enhanced production of C10 and P2224 scFvs

As described above, increasing the culture temperature from 25 to 30 °C during expression of C10 and P2224 resulted in an apparent decrease in absolute yields, and led to our efforts to enhance stability of the proteins. Although absolute yields of proteins varied between production runs, trends related to yields were observed. Despite the differences in amino acid composition and codon usage associated with the redesign process C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE were expressed and purified to approximately the same level (average: 2.5 vs 2.2 mg/L culture) when experiments were performed at 25 °C (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, C10KV3_LV1DE was purified to approximately 2.5-fold higher levels than C10 at 30 °C, a temperature that deleteriously affected expression of the parental C10 scFv. Incorporating the redesigned KV3_LV1DE light chain into P2224 had a similar effect on increasing yields. Yields of P2224KV3_LV1DE, as compared to P2224, were increased by approximately 2.5-fold when expressions were carried out at 25 °C. The effect of the redesigned P2224KV3_LV1DE was even more dramatic when expressions were carried out at 30 °C, with the yields of P2224KV3_LV1DE being approximately 8-fold greater than those obtained with P2224 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). In support of our hypothesis that incorporation of the λ1 d-e loop into C10KV3_LV1DE would be a critical structure determinant, the presence of the κ3 d-e loop in C10KV3 decreased production of the scFv by approximately 2.5 fold (Fig. 1B and E)

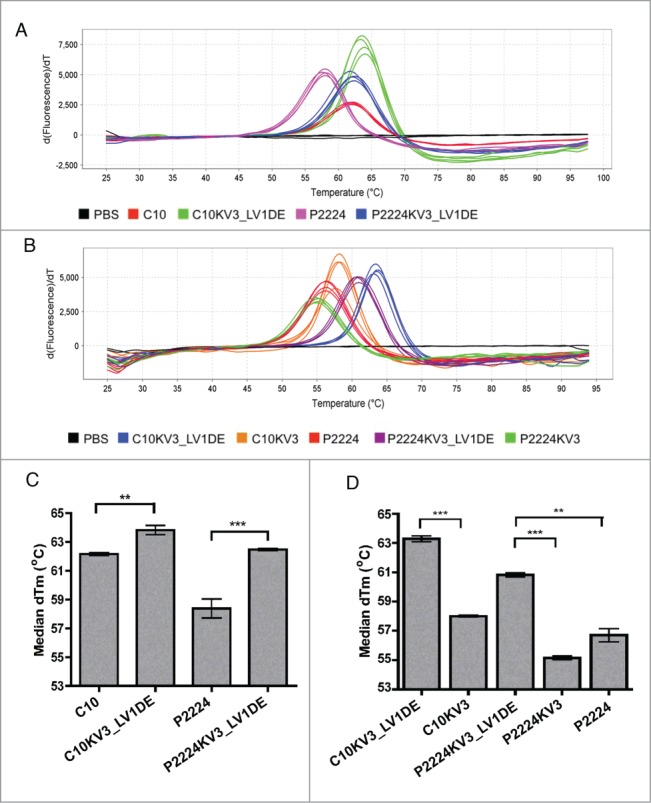

The C10KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3_LV1DE variants exhibit enhanced thermostability

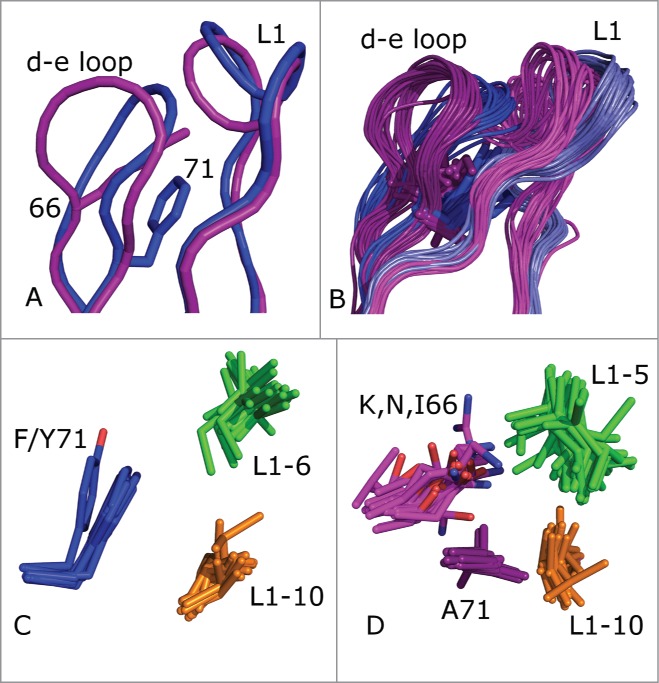

Since enhanced production of the KV3_LV1DE-redesigns is a promising indicator that the reformatted framework provides greater structural stability, we utilized differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) to examine the thermostability of C10 and its derivatives. As shown in Figure 5, C10KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3_LV1DE exhibit a greater derivative Tm (approx. 64°C and 62°C, respectively) than C10 and P2224 (approx. 62°C and 58°C, respectively). Although the Tm is enhanced by only 2–4°C, the difference between the parental and redesigned mutants is significant (Fig. 5C), and demonstrates that the κ3-based framework enhances the thermostability of these scFvs. Additionally, maintaining the original λ d-e loop of C10 proved to be critical in enhancing the thermostability of C10KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3_LV1DE as evidenced by a 5–6°C decrease in Tm of C10KV3 and P2224KV3, which contain the κ3 d-e loop (Fig. 5B and D).

Figure 5.

(A-B) The Boltzmann derivative melt profiles of indicated scFv generated from differential scanning fluorimetry. Data were generated on an Applied Biosystems® 7500 Real-Time PCR System using continuous ramp mode at 0.5% ramp rate from 25 °C through 99 °C. (C) Graph of the median derivative Tm calculated from (A). (C-D) Graph of the median derivative Boltzmann Tm (A). Error bars represent standard error of the mean of 4 (n = 4) (D) or 5 (n = 5) (C) independent experiments run in quadruplicate. P values were calculated using a one-sample t test. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

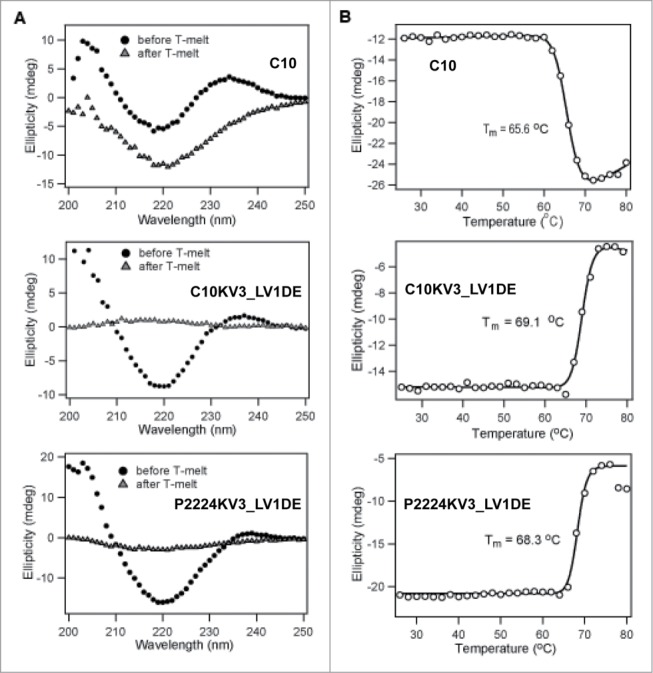

To further confirm that the framework mutants are indeed more thermodynamically stable, we analyzed C10, C10KV3_LV1DE, and P2224KV3_LV1DE by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Of note, the P2224 scFv was not analyzed in this assay because it consistently demonstrated a resistance to concentration above 1 μM, a property that has been remedied by the κ3 swap. For the rest, thermal melt scans were performed at a fixed wavelength of 218 nm to monitor β-sheet unfolding. Under this set of parameters, the ellipticity of the protein solution was recorded and C10KV3_LV1DE was deemed more thermodynamically stable (Tm = 69.1°C) than C10 (Tm = 65.6°C) due to enhanced melting temperature (Fig. 6). While the concentration of P2224 was too low to accurately calculate a Tm, P2224KV3_LV1DE also demonstrated higher thermostability (Tm = 68.3°C) than C10 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

CD analysis of 20 μM scFv. (A) Wavelength scan of scFv at 25°C pre-heat and post-heating at 80°C. (B) Ellipticity (CD signal) during thermal scan of scFv at 218nm. All data is representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

In addition to measuring the ellipticity, the dynode voltage, which can be used to calculate absorbance, was concurrently recorded to measure the heat-induced aggregation of the scFvs (Fig. 7A). Increasing absorbance is caused by variations in light scattering due to increasing particle size as a result of aggregation of the unfolded protein at elevated temperature.38 Interestingly, C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE appear to have different modes of aggregation (Fig. 7A). With increasing temperature up to 80°C, C10 demonstrates a steady increase in soluble protein aggregates, while C10KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3_LV1DE exhibit aggregation at higher temperatures that results in precipitation of insoluble protein (Fig. 7A, bell shaped curve).

Figure 7.

(A) Absorbance change derived from dynode voltage during thermal scan of 20 μM scFv at 218 nm derived from data in Figure 5. (B–C) Dynamic light scattering of 10 μM of C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE at various temperatures. (B) Averaged static molecular weight calculated over increasing temperature. (C) % mass graphed as a function of hydrodynamic radius. Data represents 20 scans of 30 secs (for a total of 10 min) at the set temperature. C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE were calculated to be >99% monomeric at 25°C. The plots are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

This different mode of protein aggregation is also reflected in the CD-detected thermal unfolding curves (Fig. 6), where C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE both appear to irreversibly unfold, while their resulting spectral signatures are qualitatively different. After heating to 80°C and cooling back to 25°C, C10 does not completely regain its native structure. In fact, C10 appears to lose signal at 205 nm back to baseline while gaining a more negative signal at 218 nm, which may reflect an increase in β like-structure or aggregation. In contrast, C10KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3_LV1DE show little or no residual CD signal after cooling back to 25°C (Fig. 6A), indicating that both proteins are completely precipitated at 80°C (Fig. 6B). The fact that the κ3 variants precipitate out of solution upon heating is not that surprising and is similar to the mode of heat-induced aggregation and precipitation of the single chain version of trastuzumab, 4D5, which is a VH3/Vκ1 antibody (Fig. 7). Overall, the measured increases in Tm for C10KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3_LV1DE compared to C10 further reinforce the idea that the newly introduced κ3 framework increases the inherent thermostability of C10 and provides support for the use of our structure-based strategy for antibody redesign.

Both C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE form large heat-induced aggregates

Since both C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE exhibit heat-induced irreversible unfolding, while the κ3 variants form visible aggregates and C10 and P2224 do not, we examined whether the κ3-redesign resulted in a change in the size and solubility of the aggregates. To do this, C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE were heated to 60°C for 10 min, cooled to room temperature, and analyzed for changes in hydrodynamic radius (or mass of an equivalent sphere) by dynamic light scattering. As shown in Figures 7B and C, the majority of C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE are predominantly monomeric at 25°C. Upon heating to 60°C, very large aggregates can be seen in both C10 and C10KV3_LV1DE preparations. This unfolding and aggregation appears to be irreversible since only large aggregates are observed when samples are cooled to 25°C and no detectable levels of monomer are present. It is interesting that solubility is maintained even for the large aggregates produced by C10. Overall the collective data suggests that the κ3 redesign improves protein production, thermostability, and, although both C10 and the C10KV3_LV1DE will form large heat-induced products, the aggregated products are qualitatively different with C10, generating large soluble products, while the C10KV3_LV1DE, like 4D5, precipitates upon heat-induced unfolding and aggregation.

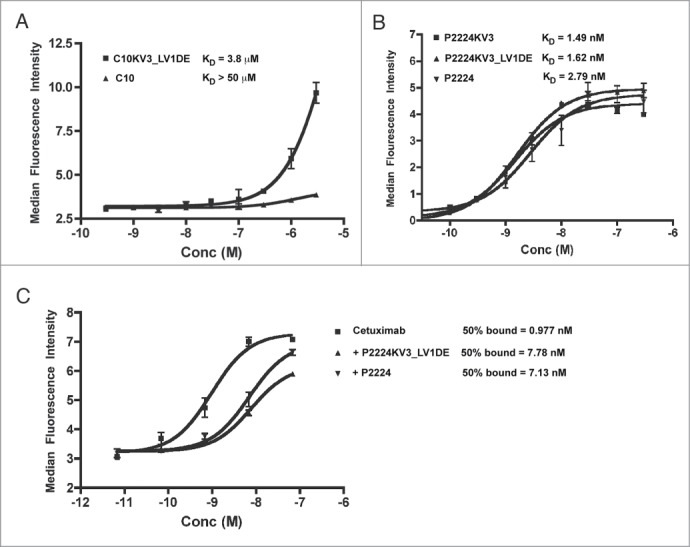

The κ3 redesigns exhibit both similar binding affinities and cetuximab blocking ability as the parental λ3-λ1 scFvs

Although the κ3 variants are more stable, it is possible that the CDR grafting altered the scFv target binding by changing the orientation of the CDRs. Therefore, we compared the abilities of the parental and redesigned scFv to bind to EGFR+ cells. Under the conditions employed in our assays C10KV3_LV1DE bound weakly to EGFR+ cells with a KD of approximately 3.8 μM. However, this binding was better than that detected for the parental C10, which failed to bind sufficiently to allow for determination of a KD (Fig. 8A). As shown in Figure 8B, the KDs for P2224, P2224KV3, and P2224KV3_LV1DE were calculated to be 2.79 nM, 1.49 nM, and 1.62 nM, respectively, thus indicating that the κ3-derived framework and d-e loop do not appear to alter affinity. Together these data demonstrate that the redesigned VL framework does not reduce the ability of the C10 and P2224 CDRs to bind cell surface EGFR.

Figure 8.

(A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of C10 and mutants. (A) A431-NS cells were stained with scFv overnight at 4°C, fixed, and detected with a mouse anti-His-FITC antibody. (C) Cells were pre-blocked with indicated scFv overnight at 4°C, stained with FITC-labeled cetuximab, fixed and analyzed. Error bars represent +/− SD of duplicate wells and the data is representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Previous studies demonstrated that P2224 elicits therapeutic activity, at least in part, by binding to domain III of EGFR's extracellular domain and competing with ligand (e.g., EGF) binding.20 Its epitope on domain III is sufficiently close to the epitope bound by cetuximab that P2224 can also compete with cetuximab for binding to EGFR.39 To confirm that the κ3 redesign did not dramatically alter the binding epitope, we examined whether P2224 and its κ3 derivatives retained the ability to block cetuximab binding. As demonstrated in Figure 8C, both P2224 and P2224CKV3_LV1DE block cetuximab binding in equivalent concentration-dependent manners. Collectively, these data demonstrate that our rational redesign of C10 and P2224 enhances protein production and thermostability without altering the antibodies' abilities to bind their target antigen.

Discussion

Our previous work took advantage of the large diversity of crystal structures available in the PDB to expand upon the original findings of Chothia40 and allowed us to delineate a sequence/structure relationship between CDRs.24 Here, we demonstrate that combining this CDR clustering24 with an analysis of CDR/framework interactions correctly guides the stability engineering of the C10 series of anti-EGFR scFvs. Molecular modeling and extensive refinement with Rosetta of C10 and λ1, λ3, and κ3 variants indicated that the κ3 variants with and without the λ1 d-e loop were the most promising candidates for engineering a stable platform for the P2224 series of antibodies.

Many properties, including affinity, effector function, and pharmacokinetics, must be considered while engineering a therapeutic antibody.41 Display techniques coupled with advances in antibody engineering have led to rapid, robust methods for both isolating antibodies against targets of interest and tailoring their behavior.42 Significant effort has been devoted to understanding the effect of affinity on biological activity and developing methods to tailor affinity for desired purposes.43-47 This is exemplified by the ability of the C10 series of anti-EGFR scFv antibodies to block EGFR signaling and inhibit cell growth in a manner that correlates with increased binding affinity.20,39 These types of data, developed across a large array of antibody/antigen pairs, have led to incorporation of affinity maturation as a critical step in therapeutic antibody development.48 As observed with C10 and P2224, altering the amino acid sequence of an antibody with the defined goal of improving binding affinity can affect other biophysical properties, such as stability, expression level, and propensity to aggregate, which are also critical for moving antibodies toward clinical development.41 Although formulation can be used to overcome poor biophysical characteristics (e.g. cetuximab's propensity to aggregate upon mechanical manipulation was addressed by a late-stage change in formulation49), it is sometimes insufficient on its own. Therefore, steps to either identify an alternative lead with similar biologic activity and better biophysical characteristics or protein engineering approaches to develop more stable, aggregation-resistant variants of the lead agent, are undertaken early in the development process.

As mentioned above, data from the Plückthun group demonstrating the superior production and stability of VH1-Vκ3 scFv50 and the subsequent work by Tiller and colleagues28 expanding this finding to IgG production and stability led us to generate CDR-grafted κ3 versions of C10 and P2224. Additionally, Honegger et al. examined to what extent the choice of “hydrophobic core” affects stability compared with the influence of the CDR/framework pairing.22 To this end, they constructed and evaluated scFv comprising one of 3 HuCAL VH3 variants that differed in their hydrophobic “lower cores,” but had unchanged CDRs, “upper cores,” and exteriors, paired with the same stable and unchanged HuCAL consensus Vκ3 chain. The authors demonstrated that switching from a VH3-Vκ1 (such as hu4D5–8,51) to a VH3-Vκ3 dramatically improved expression levels as well as thermostability.22 Of most relevance here, the authors concluded that intrinsic stability of a framework pairing is insufficient on its own to fully stabilize an scFv, highlighting that fit between the CDRs and framework is a major component of overall stability.22 This finding is consistent with a large body of literature focused on humanization of murine antibodies for the purpose of decreasing immunogenicity of therapeutic candidates (for review see ref. 52).

Humanization, pioneered by Winter and colleagues,53 takes advantage of the conserved nature of the antibody frameworks that allow for grafting of the murine CDRs onto a human acceptor framework. Strategies to select a human acceptor framework include using a well-behaved “fixed framework” or using the human germline gene that is most closely related to the parent murine antibody. Implicit in the humanization process is the need for the CDRs to retain their conformation, and thus the ability to bind antigen. As exemplified by generation of trastuzumab from mu4D5, framework residues within the parental murine antibody are often required to correctly orient the CDRs.54 Straight grafting of mu4D5 CDRs onto consensus VH3 and Vκ1 frameworks to generate hu4D5–1 resulted in an 80-fold loss of binding activity and concomitant loss of anti-proliferative activity. Creation of hu4D5–8 through back-mutation of a series of VH (amino acids 71, 73, 78, 93) and VL (amino acid 56) framework residues and 2 CDR residues (CDR-H3 residue 102 and CDR-L2 residue 55), identified via molecular modeling, improved antigen binding 250-fold over hu4D5–1 and restored anti-proliferative activity. A λ to κ framework switch has been attempted previously for an anti-GCN4 intrabody.55 Wörn et al. started with an anti-GCN4 antibody consisting of variants of IMGT mouse germline V-regions IGHV2–6–7*02 (88% identity) and IGLV1*01 (97% identity). To graft the mouse anti-GCN4 CDRs onto Vκ and VH frameworks, Wörn et al. created two mutants: one labeled κ-graft and one labeled λ-graft.55 The κ-graft was produced by replacing the VH and VL CDR sequences of another scFv (“hybrid”), consisting of the VL domain of mu4D5 (94% identical to mouse IGKV6–17*01) and the VH domain of A48++(H2) (93% identical to mouse IGHV4–1*02), with the anti-GCN4 CDRs. In addition, the κ-graft contained the d-e loop of the original mouse λ anti-GCN4 antibody and the six residues following CDR H2 plus 2 additional back mutations in the heavy chain at positions 71 and 78. Thus this design is significantly more complicated than our P2224VK3_LV1DE design, which changes only the light chain CDRs and d-e loop and does not change the heavy chain at all. The anti-GCN4 κ-graft was significantly more stable than the original anti-GCN4 antibody, but lost binding by 3 orders of magnitude.

The “λ-graft” of Wörn et al. differed from the κ-graft by only 7 amino acids at the VH/VL interface, and these changes were generated to aid in proper orientation of the domains, which successfully enhanced solubility, expression, and structural stability.55 However, the l-graft still lost an order of magnitude in KD from the anti-GCN4 mouse antibody, suggesting that other residues within the κ framework were important for maintaining CDR orientation, and thus antibody affinity.55 Our design is therefore both simpler and more effective than the approach of Wörn et al.

As mentioned above, we hypothesized that the only change required to facilitate the grafting of the Vλ3-like CDRs was the retention of the framework d-e loop, an “upper core” change that was within the range considered necessary by Plückthun et al. for successful grafting. We stabilized the upper core of C10KV3 and P2224KV3 by back-mutating the d-e loop to the λ-like sequence found in the original C10 to produce C10KV3_LV1DE and P2224KV3_LV1DE. In this process, we actually removed the bulky aromatic F71 from the upper core of the Vκ3 to make room for the probable λ-like conformation of the L1 loop, including interactions of A71 with L28 and A33, and added back the side chain of residue 66 (Gly in κ3 antibodies; Lys in C10), which affects the conformation and position of the whole d-e loop. We demonstrate that these changes enhance thermostability and expression while maintaining affinity. Interestingly, the d-e loop of the native Vκ3 version in C10KV3 and P2224KV3 decreased thermal stability and production yields, consistent with the proposed role in stabilizing the VL domain, but did not affect antigen binding. While Rosetta predicted that both κ3 variants might produce more stable antibodies than C10, it was not able to distinguish C10KV3_LV1DE from C10KV3 from an energetic standpoint, reinforcing the utility of careful structural analysis.

An increased aggregation propensity for an antibody results in reduced biological activity, increased clearance, and decreased safety, since aggregate formation can lead to aberrant immunogenic reactions. Notably, although we improved upon thermostability, the mode of aggregation between the parental and redesigned mutants drastically changed. Based on CD spectra and dynamic light scattering, C10 and P2224 demonstrate temperature-dependent irreversible unfolding with enhanced β structure, which may be caused by increased formation of large, soluble oligomers. However, the κ3 variants exhibit thermal unfolding that is more characteristic of the hu4D5 scFv (VH3/Vκ1), which demonstrates irreversible unfolding and results in aggregate precipitation.

The mechanisms governing the different unfolding properties of C10 and C10KV3 are unclear at this time. Since we observed a gain in β-signature in CD spectra, it is possible C10 and P2224 are generating soluble pre-fibrillar structures. This property is demonstrated by Bence-Jones proteins, which are over-produced light chain byproducts of multiple myeloma cells that cause light chain amyloidosis leading to insoluble amyloid fiber accumulation and vital organ failure.56,57 The specific germline genes that are over-represented in Bence-Jones proteins are predominantly of λ origin (λ1, λ2, λ3, λ4 and κ1).58 However, it should be noted that large soluble aggregates are just as toxic to cells as precipitated aggregates.59 Whether C10 and P2224 are generating soluble pre-fibrillar structures that are remedied by the κ3 swap requires further investigation.

Overall, we present here a novel method for switching a problematic Vl framework with more stable κ3 sequences. Based on structural analysis, we made rational decisions to back-mutate the flanking framework to the conserved λ residues and demonstrate that the swap created mutants with enhanced production from E. coli, reduced resistance to concentration, increased thermostability, and altered. We anticipate that the strategy we have employed will be useful in many design applications governing scFv and multispecific antibodies and provide a tool to enhance the biophysical properties of these potential therapeutics early in the engineering and selection process.

Materials and Methods

Homology modeling of C10 and designed antibodies

Sequence alignments of C10 with human germline and PDB sequences were performed with PSI-BLAST.60 C10's CDRs were grafted into the sequence of human κ3, λ3, and λ1 germline sequences by replacing the CDRs with the C10 sequences, according to the CDR definitions of North et al.,24 which are longer than the standard Chothia definitions.40 In our definitions, CDR1 and CDR3 both begin immediately after the cysteines of the disulfide bond and end just before the tryptophan or phenylalanine motifs immediately across from the cysteine, typically WV[QR]Q after L1 and H1 and [WF]G[QG]G after L3 and H3. Our L2 definition is 3 residues longer than the Chothia definition on the C-terminus and our L2 definition is 2 residues longer on each end of the CDR.

We built a homology model of the C10 scFv, consisting of a human IGHV1–69 domain and of a likely human IGLV3–19/IGLV1–44 fusion product, and for the C10 VL-CDRs grafted onto an IGKV3–20 framework (referred to as C10KV3). The C10 mutations giving rise to P2224, which are predominantly located in the VH1 heavy chain, were added to the models of C10 and C10KV3 to produce models of P2224 and P2224KV3, respectively. Seeking to minimize the number of templates used in our C10 homology model, templates for framework and CDRs were not selected sequentially, but were considered simultaneously because we aimed to select framework templates that already contain CDRs in the correct conformations. We focused on CDRs H1 and L1 first, in conjunction with the framework choice. CDRs L2 and H2 were modeled directly on their donor framework loops as these loops in many cases preserve a common backbone structure and only display sequence variability. Choices for H3 and L3 were made together as we found an antibody structure with high homologies in both loops that provided a good model for the L3-H3 interaction.

We chose PDB entry 2G7561 as the C10 wild-type template because it consists of an IGHV1/IGLV3 variable domain pair like the C10 antibody. As a λ3/λ1 fusion, the Vλ3 chain still contains approximately 2/3 of the λ3 light chain, so 2G75 represents this antibody well. The CDRs of 2G75 represent the most likely conformations of H1 (H1–13–10), H2 (H2–10–1), L1 (L1–11–3), and L2 (L2–8–1).24,29 The C10 model based on 2G75 requires grafting the L3-H3 coordinates from another structure, since the CDR3 lengths in 2G75 are not the same as those in C10. We chose PDB entry 2FB4,62 an IGHV3–30/IGLV1–44 framework, for both grafts. The grafted 2FB4 L3 backbone was left unchanged, while the grafted 2FB4 H3 was in part remodeled using the UCSF Chimera package and its interface to Modeler.63 In the partial remodeling of the H3, we preserved the disulfide-bonded loop in 2FB4 (sequence CSSASC) to model the same segment in C10 (sequence CSSTSC) and most of the interface with L3.

The H1, L1, H3, and L3 CDRs from the C10 model were grafted onto the structure of an IGHV1–69/IGKV3–20 antibody (PDB 1RHH30) in order to model C10KV3. The acceptor H2 (H2–10–1) and L2 (L2–8–1) backbones were left unchanged because they belong to identical clusters for parent and acceptor frameworks, respectively. The side-chain packing of all models was optimized using the program SCWRL4.64

We also modeled C10 and the C10LV1, C10LV3, and C10KV3 variants with the RosettaAntibody webserver65 with standard parameters but without the option of extensive modeling of H3. A model of C10KV3_LV1DE was constructed by manually grafting the d-e loop from PDB entry 4GXV35 with the same sequence as the d-e loop of C10 (KSGTSA). Structures were analyzed and examined in Pymol (Schrödinger, Inc.). Clusters of the CDRs in the models were determined with our PyIgClassify website.29

The RosettaAntibody models were refined in a 2-stage procedure using the program Rosetta (version 3.6, release May 11, 2015). The first step was to idealize the bond lengths and bond angles of all of the models with the command line:

idealize.linuxgccrelease –s filename.pdb

The second step was to generate 250 decoys by running the mixed dihedral-angle/Cartesian-coordinate minimization protocol referred to as “dual-space relax”,36 starting from the idealized structures. The protocol runs 3 cycles of “fast relax” in dihedral angle space and 2 cycles of Cartesian minimization, which allows bond angles and bond lengths to change. The FastRelax protocol consists of 5 rounds of the following: multiplying the repulsive van der Waals parameters by a scale factor C (0<C≤1 ), several rounds of replacement of all side chains with random rotamers from our library36 with Metropolis criterion acceptance, and then continuous energy minimization of the backbone and side chains. The factor C is ramped up from 0.02 to 1.0 in each round. The lowest energy structure when C=1 is saved as a decoy, and passed to the next cycle of minimization. The dual-space relax command line is given here:

relax.linuxgccrelease -dual_space -non_ideal -shapovalov_lib_fixes_enable -nstruct 250 -s filename.pdb

The flag “-shapovalov_lib_fixes_enable” instructs Rosetta to use updated Ramachandran scoring functions (rama and P_aa_pp), which we have recently developed based on kernel density estimates of the backbone conformations of the 20 amino acids.37]

Cloning, expression, and purification of scFvs

The C10 and P2224 scFv genes, kindly provided by Dr. James Marks (University of California San Francisco), were previously described19,20,39 and the C10KV3_LV1DE coding sequence was constructed by gene synthesis. All three gene were cloned into the pSyn2 bacterial expression plasmid.66 To create P2224KV3_LV1DE, the P2224 affinity mutations were introduced into C10KV3_LV1DE by site-directed mutagenesis in a 2-step process using the Quikchange II site-directed mutagenesis kit and the following primers: FWD P24 G113A 1RHH, REV P24 G113A 1RHH, FWD P22 ST GI 1RHH, and REV P22 ST GI 1RHH (Supplementary Table 2). The kappa DE-loop back-graft mutations (to generate C10KV3 and P2224KV3 were generated by conventional site-directed mutagenesis (Quikchange II) using the following primers: FWD C10k3_deGDF and REV C10k3_deGDF. (Supplementary Table 2).

For protein production, TG-1 cells were transformed with sequence-verified clones of pSyn2 scFv-expressing constructs and induced to produce soluble scFv under conditions of osmotic pressure as previously reported.67 In short, bacterial cultures grown to OD600 = 0.8 in 2 L flasks, were pelleted and resuspended in 0.5 L of 2XYT media containing 0.5 mM IPTG, 0.4 M sucrose, and 100 mg/ml carbenicillin and cultured for 16 hr at 25°C or 30°C, as appropriate. Following dialysis into Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the soluble scFv fraction was recovered from the culture supernatant by IMAC affinity chromatography as previously described.68 Initial preparations were further analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography over a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl 100 column at a flow rate of 1 ml/min using an AKTA Prime+ (GE Healthcare). Resulting chromatographs were compared to known protein standards as previously described69 and deemed predominantly monomeric. Following IMAC purification, the preps were confirmed to be > 99% monomeric by dynamic light scattering (described below).

Circular dichroism, turbidity, and Tm measurements

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra, thermal unfolding curves, and turbidity (dynode voltage) were recorded using an Aviv 62DS spectropolarimeter using thermostatted cells with an optical path length of 1 mm. Ellipticity readings were time averaged for up to 10 sec at 60 points/s. The bandwidth was set to 2 nm and the dynode voltage was initially kept below 400 V at 25°C. CD spectra over the range from 195 to 250 nm were recorded on indicated scFv in 20 mM potassium phosphate at neutral pH.

To calculate derivative Tm by differential scanning fluorimetry, each scFv was analyzed at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL in a 20 ml volume plated in quadruplicate in MicroAmp fast optical 96-well titer plates using the Protein Thermal Shift™ (Applied Biosystems) assay. PBS was used as a baseline control. Data were generated on an Applied Biosystems® 7500 Real-Time PCR System using continuous ramp mode at 0.5% ramp rate from 25°C through 95°C. Data were analyzed using the Protein Thermal Shift™ Software.

Dynamic light scattering

Dynamic light scattering experiments were performed on a DynaPro Molecular Sizing Instrument with Dynamics V6 data analysis software (Protein Solutions, Inc.) on 80 μl of a 10 μM solution of purified scFv in PBS. Autocorrelation curves were acquired for a total acquisition time of 600 s at each temperature.

Flow cytometric analysis

A431-NS cells (ATCC #CRL-2592) were grown to sub-confluence and harvested in Ca2+/Mg2+ free PBS containing 1 mM EDTA. Cells were washed, resuspended in FACS buffer (1% BSA, 0.1% sodium azide, PBS), and plated at 2 × 105 cells/well in 96-well round-bottom tissue culture plates. To evaluate scFv binding to the cells under conditions of equilibrium, the reaction took place overnight at 4°C. The next day cells were washed and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, and cell-bound scFv was detected with 1 mg/ml FITC-labeled Penta-His antibody (Qiagen) for 1 hour on ice. Cells were washed, fixed again, and analyzed. To determine whether P2224 or P2224KV3_LV1DE blocked cetuximab binding, cells were pre-bound with 3 μM of the indicated scFv overnight at 4°C. The next day, cetuximab was pre-labeled with equimolar concentrations of FITC-conjugated donkey anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 30 min on ice. The cetuximab:FITC conjugate was applied to the scFv pre-blocked cells for 1 hour on ice. Cells were washed again and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. All fluorescently labeled cells were acquired using a FACScan instrument (Becton Dickinson) and the data were analyzed by FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark Andrake for aid in dynamic light scattering acquisition and to the Spectroscopy Support Facility for providing access to CD spectroscopy.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the NIH Cancer Center Support Grant CA06927 to Fox Chase Cancer Center, as well as NIH grants T32 CA009035 to J.F.W., R01 GM084453 and R01 GM111819 to R.L.D., and R21 CA181868 to M.K.R. was partially supported by a grant from the Rosetta Commons (rosettacommons.org).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1.Nelson AL, Dhimolea E, Reichert JM. Development trends for human monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010; 9:767-74; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20811384; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrd3229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad ZA, Yeap SK, Ali AM, Ho WY, Alitheen NB, Hamid M. Scfv antibody: Principles and clinical application. Clin Dev Immunol 2012; 2012:980250; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22474489; PMID:22474489; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2012/980250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riethmuller G. Symmetry breaking: Bispecific antibodies, the beginnings, and 50 years on. Cancer Immun 2012; 12:12; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22896757; PMID:22896757 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrne H, Conroy PJ, Whisstock JC, O'Kennedy RJ. A tale of two specificities: Bispecific antibodies for therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Trends Biotechnol 2013; 31:621-32; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24094861; PMID:24094861; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castoldi R, Jucknischke U, Pradel LP, Arnold E, Klein C, Scheiblich S, Niederfellner G, Sustmann C. Molecular characterization of novel trispecific erbb-cmet-igf1r antibodies and their antigen-binding properties. Protein Eng Des Sel 2012; 25:551-9; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22936109; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/protein/gzs048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maus MV, Grupp SA, Porter DL, June CH. Antibody-modified t cells: Cars take the front seat for hematologic malignancies. Blood 2014; 123:2625-35; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24578504; PMID:24578504; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2013-11-492231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazan J, Calkosinski I, Gamian A. Phage display–a powerful technique for immunotherapy: 1. Introduction and potential of therapeutic applications. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2012; 8:1817-28; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22906939; PMID:22906939; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.21703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowe D, Dudgeon K, Rouet R, Schofield P, Jermutus L, Christ D. Aggregation, stability, and formulation of human antibody therapeutics. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2011; 84:41-61; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21846562; PMID:21846562; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-12-386483-3.00004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee CC, Perchiacca JM, Tessier PM. Toward aggregation-resistant antibodies by design. Trends Biotechnol 2013; 31:612-20; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23932102; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jefferis R. Aggregation, immune complexes and immunogenicity. mAbs 2011; 3:503-4; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22123066; PMID:22123066; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/mabs.3.6.17611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baneyx F, Mujacic M. Recombinant protein folding and misfolding in escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol 2004; 22:1399-408; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15529165; PMID:15529165; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bondos SE, Bicknell A. Detection and prevention of protein aggregation before, during, and after purification. Anal Biochem 2003; 316:223-31; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12711344; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0003-2697(03)00059-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu ZJ, Deng SJ, Huang DG, He Y, Lei M, Zhou L, Jin P. Frontier of therapeutic antibody discovery: The challenges and how to face them. World J Biol Chem 2012; 3:187-96; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23275803; PMID:23275803; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4331/wjbc.v3.i12.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arteaga CL, Engelman JA. Erbb receptors: From oncogene discovery to basic science to mechanism-based cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell 2014; 25:282-303; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24651011; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, Remenar E, Kawecki A, Rottey S, Erfan J, Zabolotnyy D, Kienzer HR, Cupissol D, et al.. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1116-27; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18784101; PMID:18784101; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D'Haens G, Pinter T, Lim R, Bodoky G, et al.. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1408-17; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19339720; PMID:19339720; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham D, Jassem J, et al.. Final results from prime: Randomized phase iii study of panitumumab with folfox4 for first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2014; 25:1346-55; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24718886; PMID:24718886; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/annonc/mdu141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roskoski R., Jr The erbb/her family of protein-tyrosine kinases and cancer. Pharmacol Res 2014; 79:34-74; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24269963; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heitner T, Moor A, Garrison JL, Marks C, Hasan T, Marks JD. Selection of cell binding and internalizing epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies from a phage display library. J Immunol Methods 2001; 248:17-30; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11223066; PMID:11223066; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0022-1759(00)00340-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Goenaga AL, Harms BD, Zou H, Lou J, Conrad F, Adams GP, Schoeberl B, Nielsen UB, Marks JD. Impact of intrinsic affinity on functional binding and biological activity of egfr antibodies. Mol Cancer Ther 2012; 11:1467-76; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22564724; PMID:22564724; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dudgeon K, Rouet R, Christ D. Rapid prediction of expression and refolding yields using phage display. Protein Eng Des Sel 2013; 26:671-4; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23690626; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/protein/gzt019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honegger A, Malebranche AD, Rothlisberger D, Pluckthun A. The influence of the framework core residues on the biophysical properties of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable domains. Protein Eng Des Sel 2009; 22:121-34; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19136675; PMID:19136675; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/protein/gzn077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichols P, Li L, Kumar S, Buck PM, Singh SK, Goswami S, Balthazor B, Conley TR, Sek D, Allen MJ. Rational design of viscosity reducing mutants of a monoclonal antibody: Hydrophobic versus electrostatic inter-molecular interactions. mAbs 2015; 7:212-30; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25559441; PMID:25559441; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/19420862.2014.985504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.North B, Lehmann A, Dunbrack RL Jr. A new clustering of antibody cdr loop conformations. J Mol Biol 2011; 406(2):228-56; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21035459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung S, Pluckthun A. Improving in vivo folding and stability of a single-chain fv antibody fragment by loop grafting. Protein Eng 1997; 10:959-66; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9415446; PMID:9415446; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/protein/10.8.959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V, Ginestoux C, Jabado-Michaloud J, Folch G, Bellahcene F, Wu Y, Gemrot E, Brochet X, Lane J, et al.. Imgt, the international immunogenetics information system. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:D1006-1012; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18978023; PMID:18978023; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkn838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ewert S, Honegger A, Pluckthun A. Structure-based improvement of the biophysical properties of immunoglobulin vh domains with a generalizable approach. Biochemistry 2003; 42:1517-28; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12578364; PMID:12578364; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi026448p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tiller T, Schuster I, Deppe D, Siegers K, Strohner R, Herrmann T, Berenguer M, Poujol D, Stehle J, Stark Y, et al.. A fully synthetic human fab antibody library based on fixed vh/vl framework pairings with favorable biophysical properties. mAbs 2013; 5:445-70; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23571156 https://http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/mabs/2012MABS0336R.pdf; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/mabs.24218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adolf-Bryfogle J, Xu Q, North B, Lehmann A, Dunbrack RL Jr. Pyigclassify: A database of antibody cdr structural classifications. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43:D432-438; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25392411 http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/43/D1/D432.full.pdf; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gku1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darbha R, Phogat S, Labrijn AF, Shu Y, Gu Y, Andrykovitch M, Zhang MY, Pantophlet R, Martin L, Vita C, et al.. Crystal structure of the broadly cross-reactive hiv-1-neutralizing fab x5 and fine mapping of its epitope. Biochemistry 2004; 43:1410-7; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14769016; PMID:14769016; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi035323x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moulard M, Phogat SK, Shu Y, Labrijn AF, Xiao X, Binley JM, Zhang MY, Sidorov IA, Broder CC, Robinson J, et al.. Broadly cross-reactive hiv-1-neutralizing human monoclonal fab selected for binding to gp120-cd4-ccr5 complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002; 99:6913-8; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11997472; PMID:11997472; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.102562599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bork P, Holm L, Sander C. The immunoglobulin fold. Structural classification, sequence patterns and common core. J Mol Biol 1994; 242:309-20; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7932691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theobald DL, Wuttke DS. Theseus: Maximum likelihood superpositioning and analysis of macromolecular structures. Bioinformatics 2006; 22:2171-2; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16777907; PMID:16777907; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ting D, Wang G, Shapovalov M, Mitra R, Jordan MI, Dunbrack RL Jr. Neighbor-dependent ramachandran probability distributions of amino acids developed from a hierarchical dirichlet process model. PLoS Computat Biol 2010; 6:e1000763; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20442867; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsibane T, Ekiert DC, Krause JC, Martinez O, Crowe JE Jr., Wilson IA, Basler CF. Influenza human monoclonal antibody 1f1 interacts with three major antigenic sites and residues mediating human receptor specificity in h1n1 viruses. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1003067; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23236279; PMID:23236279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conway P, Tyka MD, DiMaio F, Konerding DE, Baker D. Relaxation of backbone bond geometry improves protein energy landscape modeling. Protein Sci 2014; 23:47-55; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24265211; PMID:24265211; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/pro.2389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shapovalov MV, Dunbrack RL Jr. A smoothed backbone-dependent rotamer library for proteins derived from adaptive kernel density estimates and regressions. Structure 2011; 19:844-58; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21645855; PMID:21645855; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.str.2011.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benjwal S, Verma S, Rohm KH, Gursky O. Monitoring protein aggregation during thermal unfolding in circular dichroism experiments. Protein Sci 2006; 15:635-9; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16452626; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1110/ps.051917406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Y, Drummond DC, Zou H, Hayes ME, Adams GP, Kirpotin DB, Marks JD. Impact of single-chain fv antibody fragment affinity on nanoparticle targeting of epidermal growth factor receptor-expressing tumor cells. J Mol Biol 2007; 371:934-47; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17602702; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Lazikani B, Lesk AM, Chothia C. Standard conformations for the canonical structures of immunoglobulins. J Mol Biol 1997; 273:927-48; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9367782; PMID:9367782; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Igawa T, Tsunoda H, Kuramochi T, Sampei Z, Ishii S, Hattori K. Engineering the variable region of therapeutic igg antibodies. mAbs 2011; 3:243-52; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21406966; PMID:21406966; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/mabs.3.3.15234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weaver-Feldhaus JM, Miller KD, Feldhaus MJ, Siegel RW. Directed evolution for the development of conformation-specific affinity reagents using yeast display. Protein Eng Des Sel 2005; 18:527-36; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16186140; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/protein/gzi060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Y, Guo Q, Xia M, Li Y, Peng X, Liu T, Tong X, Xu J, Guo H, Qian W, et al.. Generation and characterization of a target-selectively activated antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor with enhanced anti-tumor potency. mAbs 2015; 7:440-50; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25679409; PMID:25679409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rudnick SI, Adams GP. Affinity and avidity in antibody-based tumor targeting. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2009; 24:155-61; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19409036; PMID:19409036; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/cbr.2009.0627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams GP, Schier R, Marshall K, Wolf EJ, McCall AM, Marks JD, Weiner LM. Increased affinity leads to improved selective tumor delivery of single-chain fv antibodies. Cancer Res 1998; 58:485-90; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9458094; PMID:9458094 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schier R, McCall A, Adams GP, Marshall KW, Merritt H, Yim M, Crawford RS, Weiner LM, Marks C, Marks JD. Isolation of picomolar affinity anti-c-erbb-2 single-chain fv by molecular evolution of the complementarity determining regions in the center of the antibody binding site. J Mol Biol 1996; 263:551-67; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8918938; PMID:8918938; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wittrup KD, Thurber GM, Schmidt MM, Rhoden JJ. Practical theoretic guidance for the design of tumor-targeting agents. Methods Enzymol 2012; 503:255-68; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22230572; PMID:22230572; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-12-396962-0.00010-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prassler J, Steidl S, Urlinger S. In vitro affinity maturation of hucal antibodies: Complementarity determining region exchange and rapmat technology. Immunotherapy 2009; 1:571-83; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20635988; PMID:20635988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lahlou A, Blanchet B, Carvalho M, Paul M, Astier A. Mechanically-induced aggregation of the monoclonal antibody cetuximab. Ann Pharm Fr 2009; 67:340-52; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19695370; PMID:19695370; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pharma.2009.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ewert S, Huber T, Honegger A, Pluckthun A. Biophysical properties of human antibody variable domains. J Mol Biol 2003; 325:531-53; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12498801; PMID:12498801; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01237-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eigenbrot C, Randal M, Presta L, Carter P, Kossiakoff AA. X-ray structures of the antigen-binding domains from three variants of humanized anti-p185her2 antibody 4d5 and comparison with molecular modeling. J Mol Biol 1993; 229:969-95; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8095303 http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0022283683710995/1-s2.0-S0022283683710995-main.pdf?_tid=c457f9de-11e1-11e4-8422-00000aab0f26&acdnat=1406062389_b5802c5bea05162f9e5b0d04ca8d4ac5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lo BK. Antibody humanization by cdr grafting. Methods Mol Biol 2004; 248:135-59; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=14970494; PMID:14970494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winter G, Harris WJ. Humanized antibodies. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1993; 14:139-43; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8212307; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90197-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carter P, Fendly BM, Lewis GD, Sliwkowski MX. Development of herceptin. Breast Dis 2000; 11:103-11; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15687596; PMID:15687596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Worn A, Auf der Maur A, Escher D, Honegger A, Barberis A, Pluckthun A. Correlation between in vitro stability and in vivo performance of anti-gcn4 intrabodies as cytoplasmic inhibitors. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:2795-803; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10644744; PMID:10644744; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: Clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol 1995; 32:45-59; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7878478; PMID:7878478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poshusta TL, Katoh N, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Ramirez-Alvarado M. Thermal stability threshold for amyloid formation in light chain amyloidosis. Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14:22604-17; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24248061; PMID:24248061; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms141122604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poshusta TL, Sikkink LA, Leung N, Clark RJ, Dispenzieri A, Ramirez-Alvarado M. Mutations in specific structural regions of immunoglobulin light chains are associated with free light chain levels in patients with al amyloidosis. PLoS One 2009; 4:e5169; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19365555; PMID:19365555; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0005169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shin TM, Isas JM, Hsieh CL, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Langen R, Chen J. Formation of soluble amyloid oligomers and amyloid fibrils by the multifunctional protein vitronectin. Mol Neurodegener 2008; 3:16; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18939994; PMID:18939994; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1750-1326-3-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped blast and psi-blast: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:3389-402; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9254694; PMID:9254694; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prabakaran P, Gan J, Feng Y, Zhu Z, Choudhry V, Xiao X, Ji X, Dimitrov DS. Structure of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with neutralizing antibody. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:15829-36; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16597622; PMID:16597622; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M600697200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kratzin HD, Palm W, Stangel M, Schmidt WE, Friedrich J, Hilschmann N. [the primary structure of crystallizable monoclonal immunoglobulin igg1 kol. Ii. Amino acid sequence of the l-chain, gamma-type, subgroup i]. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler 1989; 370:263-72; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2713105; PMID:2713105; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1515/bchm3.1989.370.1.263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang Z, Lasker K, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Webb B, Huang CC, Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Meng EC, Sali A, Ferrin TE. Ucsf chimera, modeller, and imp: An integrated modeling system. J Struct Biol 2012; 179:269-78; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21963794; PMID:21963794; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krivov GG, Shapovalov MV, Dunbrack RL Jr. Improved prediction of protein side-chain conformations with scwrl4. Proteins 2009; 77:778-95; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19603484; PMID:19603484; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/prot.22488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sircar A, Kim ET, Gray JJ. Rosettaantibody: Antibody variable region homology modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:W474-479; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19458157; PMID:19458157; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkp387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yuan QA, Simmons HH, Robinson MK, Russeva M, Marasco WA, Adams GP. Development of engineered antibodies specific for the mullerian inhibiting substance type ii receptor: A promising candidate for targeted therapy of ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2006; 5:2096-105; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16928831; PMID:16928831; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kipriyanov SM, Moldenhauer G, Little M. High level production of soluble single chain antibodies in small-scale escherichia coli cultures. J Immunol Methods 1997; 200:69-77; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9005945; PMID:9005945; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0022-1759(96)00188-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Horak E, Heitner T, Robinson MK, Simmons HH, Garrison J, Russeva M, Furmanova P, Lou J, Zhou Y, Yuan QA, et al.. Isolation of scfvs to in vitro produced extracellular domains of egfr family members. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2005; 20:603-13; http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/abs/10.1089/cbr.2005.20.603?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dncbi.nlm.nih.gov http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16398612; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/cbr.2005.20.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robinson MK, Doss M, Shaller C, Narayanan D, Marks JD, Adler LP, Gonzalez Trotter DE, Adams GP. Quantitative immuno-positron emission tomography imaging of her2-positive tumor xenografts with an iodine-124 labeled anti-her2 diabody. Cancer Res 2005; 65:1471-8; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15735035; PMID:15735035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.