Abstract

Cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates (CLIs) are common in routine dermatopathology. However, differentiating a reactive CLI from a malignant lymphocytic infiltrate is often a significant challenge since many inflammatory dermatoses can clinically and/or histopathologically mimic cutaneous lymphomas, coined pseudolymphomas. We conducted a literature review from 1966 to July 1, 2015, at PubMed.gov using the search terms: Cutaneous lymphoma, cutaneous pseudolymphoma, cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia, simulants/mimics/imitators of cutaneous lymphomas, and cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates. The diagnostic approach to CLIs and the most common differential imitators of lymphoma is discussed herein based on six predominant morphologic and immunophenotypic, histopathologic patterns: (1) Superficial dermal T-cell infiltrates (2) superficial and deep dermal perivascular and/or nodular natural killer/T-cell infiltrates (3) pan-dermal diffuse T-cell infiltrates (4) panniculitic T-cell infiltrates (5) small cell predominant B-cell infiltrates, and (6) large-cell predominant B-cell infiltrates. Since no single histopathological feature is sufficient to discern between a benign and a malignant CLI, the overall balance of clinical, histopathological, immunophenotypic, and molecular features should be considered carefully to establish a diagnosis. Despite advances in ancillary studies such as immunohistochemistry and molecular clonality, these studies often display specificity and sensitivity limitations. Therefore, proper clinicopathological correlation still remains the gold standard for the precise diagnosis of CLIs.

Keywords: Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia, cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates, cutaneous lymphoma, cutaneous pseudolymphoma, simulants of cutaneous lymphomas

Introduction

What was known?

Cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates represent a significant diagnostic challenge. A proper diagnosis requires clinicopathological correlation and proper interpretation of ancillary studies.

Cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates (CLIs) can be seen in both benign and malignant disorders, with the latter being primary to the skin or represent secondary cutaneous dissemination.[1] Differentiating benign from malignant infiltrates is one of the most difficult tasks in dermatopathology as considerable histopathological overlap exists among primary and secondary cutaneous lymphomas and between these conditions and some inflammatory dermatoses that clinically and/or histopathologically may mimic cutaneous lymphomas, termed pseudolymphomas.[1,2,3] Accurate distinction between these conditions is critical since it affects prognosis and therapeutic management; misdiagnoses may lead to unwanted medical and psychological consequences. Thus, when approaching a CLI, the pathologist must have considerable expertise in dermatopathology and hematopathology, comfort to properly indicate and explore ancillary techniques, and most importantly, willingness to effectively communicate with the referring physician and thoroughly analyze clinical findings on a case-by-case basis.

The current World Health Organization/European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCLs) recognizes 15 separate neoplasms albeit some are still regarded as provisional entities given their rarity. Less frequently, many types of extracutaneous lymphomas may secondarily affect the skin; thus, a diagnosis of most PCL can only be rendered if a complete staging evaluation to exclude extracutaneous disease is undertaken at the time of diagnosis.[4]

In this paper, the authors provide an approach to the main differential diagnoses posed by CLI, taking as a starting point the primary patterns of infiltration combined with the immunophenotype. The entities described in this paper do not include the entirety of diseases that may present histopathologically as a predominantly CLI; rather, we have included the main cutaneous simulants of lymphoma and compared them to PCL. Moreover, certain entities that are lumped in this review under a certain pattern of infiltration and immunophenotype sometimes show an alternative histopathological pattern. This is particularly the case for drug reactions.[5,6] Furthermore, while the true nature of some disorders discussed in this paper, i.e., reactive versus malignant, remains controversial, in-depth discussion of such controversies is not provided.

The authors performed a literature review from 1966 to July 1, 2015, at PubMed.gov using the search terms cutaneous lymphoma, cutaneous pseudolymphoma, cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (CLH), simulants/mimics/imitators of cutaneous lymphomas, and cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates. The language was not restricted.

In this paper, we discuss the major advantages and limitations of each separate set of criteria when analyzing a CLI and highlight the importance of correlating these factors to render a proper diagnosis. Other practical algorithmic approaches for differentiating between reactive and neoplastic CLI have been published by the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas[7] and by the French National Cancer Institute (INCa).[3]

Diagnostic Approach Based on the Predominant Morphologic and Immunophenotypic Pattern

Superficial dermal T-cell infiltrate

In a patient with discrete erythematous lesions, a superficial T-cell predominant-dermal infiltrate (SDI) can pose the challenge of distinguishing between early patch-stage mycosis fungoides (MF) and inflammatory conditions such as a medication reaction, psoriasiform dermatitis, spongiotic dermatitis, lichenoid dermatitis, and persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis (PPPD) [Table 1 and Figures 1, 2].[3,8,9] In a patient with erythroderma, an SDI poses the differential diagnosis of Sézary syndrome (SS)/erythrodermic MF and a reactive erythroderma secondary to a medication or the worsening of a preexistent dermatosis such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, or pityriasis rubra pilaris.[10,11,12,13,14,15,16]

Table 1.

Superficial dermal T-cell infiltrate

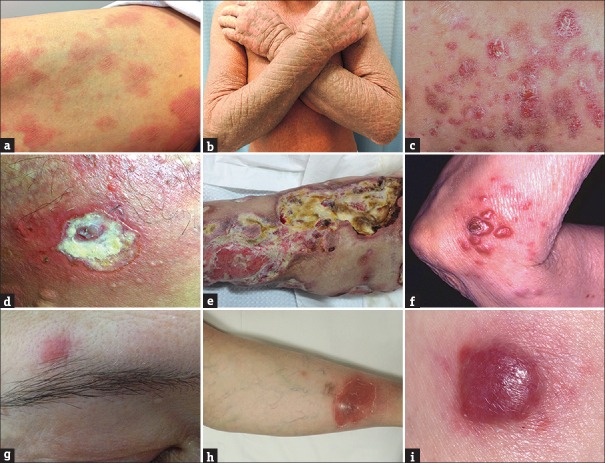

Figure 1.

Clinical examples of inflammatory cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates. (a) Sharply demarcated plaques with thick scale in psoriasis; (b) erythematous scaly patches with lichenification in allergic contact dermatitis; (c) drug-induced morbilliform exanthem; (d) hypopigmented, atrophic plaques in lichen sclerosus; (e) red to golden brown macules on the lower extremities in persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis; (f) hemorrhagic, ulcerated papules in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta; (g) erythematous papules and nodules in persistent arthropod bite reaction; (h) atrophic plaque with adherent scale and pigmentary change in discoid lupus erythematosus; (i) subcutaneous red nodules on the face in lupus profundus

Figure 2.

Clinical examples of neoplastic cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates. (a) Polymorphous erythematous “wrinkly” patches in mycosis fungoides; (b) scaly erythroderma in Sézary syndrome; (c) clustered erythematous papules and nodules in lymphomatoid papulosis; (d) ulcerated plaque in extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma; (e) rapidly-growing, ulcerated plaques in primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma (postmortem image); (f) large, clustered, erythematous nodules in primary cutaneous-anaplastic large cell lymphoma; (g) single erythematous nodule in small-medium pleomorphic CD4+ T-cell lymphoma; (h) large, erythematous, subcutaneous nodule in subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma; (i) rapidly growing, erythematous to violaceous tumor in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Early patch-stage MF is clinically characterized by the insidious onset of polymorphous erythematous “wrinkly” patches, usually ≥5 cm in diameter, on sun-protected sites (buttocks, axilla, upper thighs, breast, and lower abdomen). The patches often have overlying fine white scale and are frequently asymptomatic although occasionally they can be pruritic. Progression of disease is characterized by development of plaques, tumors, erythroderma, blood, and/or visceral involvement.[17,18,19,20] Histopathologically, diagnostic biopsies of patch-stage MF are characterized by a psoriasiform and lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes with epidermotropism, cytologic atypia, and superficial dermal fibrosis [Figure 3].[21,22,23,24,25,26,27]

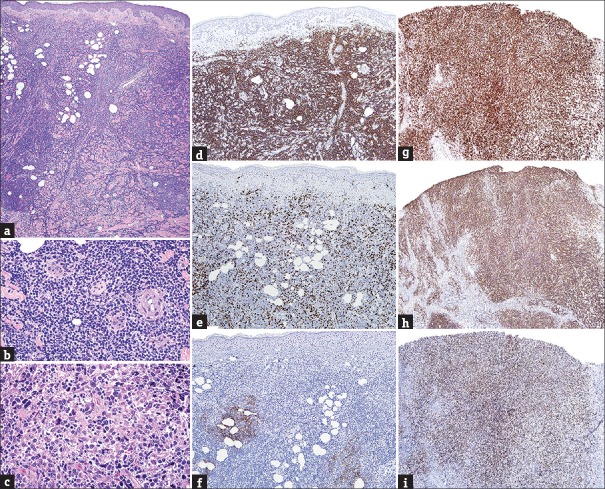

Figure 3.

(a) Superficial band-like T-cell infiltrate in early mycosis fungoides (H and E, ×20); (b) epidermotropism and lymphocytic atypia in early mycosis fungoides (H and E, ×200); (c) perivascular superficial dermal T-cell infiltrate with acanthosis in psoriasiform dermatitis (H and E, ×20); (d) hyper-parakeratosis, acanthosis, and tortuous capillaries in psoriasiform dermatitis (H and E, ×200); (e) perivascular superficial dermal T-cell infiltrate in spongiotic dermatitis (H and E, ×20); (f) spongiosis and Langerhans cells collections in spongiotic dermatitis (H and E, ×200); (g) dense band-like superficial dermal T-cell infiltrate in lichenoid dermatitis (H and E, ×20); (h) conspicuous interface changes in lichenoid dermatitis (H and E, ×200)

By contrast, psoriasiform dermatitis can be distinguished from early patch-stage MF by a perivascular (rather than band-like) SDI which includes neutrophils and surrounds tortuous and dilated papillary dermal blood vessels, coupled with regular epidermal hyperplasia, hypogranulosis, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and frequently intracorneal or intraspinous neutrophilic microabscesses.[28,29,30,31,32] Spongiotic dermatitis again displays a perivascular (rather than band-like) SDI and areas of pronounced spongiosis without many lymphocytes. When present, numerous eosinophils and intraepidermal, vase-like shaped, Langerhans cell collections favor the diagnosis of spongiotic dermatitis.[33,34,35,36,37] Lichenoid dermatoses are distinguished by a dense infiltrate obscuring the dermoepidermal junction coupled with interface changes (vacuolar change, alteration in the shape of the rete ridges, dyskeratotic cells/colloid bodies) dominating the histopathological picture as opposed to appearing only in small foci.[38,39] PPPD, which typically only affects the skin of lower extremities, is characterized by a perivascular to dense, band-like SDI, which may be accompanied by dermal fibrosis or edema, erythrocyte extravasation, and accumulation of siderophages. When lymphocytes are present within the epidermis, these typically remain in the basal layer, as opposed to colonization of the upper spinous layers, as seen in MF.[40,41] In an erythrodermic patient, SS can be distinguished from erythroderma due to an inflammatory dermatitis by the following features: Abrupt onset of de novo erythroderma and lymphadenopathy in association with neoplastic peripheral blood lymphocytosis (positive T-cell receptor gene rearrangement polymerase chain reaction [TCR-PCR], ≥1000 lymphocytes/μL, CD4 to CD8 ratio ≥10, loss of CD7 expression in ≥40% of CD4+ lymphocytes, and/or loss of CD26 expression in ≥30% of CD4+ lymphocytes).[10,11,16,42]

Despite these distinguishing features, a definite diagnosis will occasionally be impossible to reach based on the clinical and histopathological features. This is in part due to the subtle findings on biopsies of early MF which may show spongiosis and/or psoriasiform changes with only scant epidermotropism.[7,43,44] In these cases, deciding whether to pursue often-costly ancillary tests becomes challenging, particularly in resource-limited locations. Both immunohistochemistry (IHC) and TCR-PCR have been proposed as ancillary studies to be used in nondiagnostic cases. In particular, some studies have suggested that the detection of an aberrant immunophenotype with loss of pan-T-cell antigens, such as CD2, CD5, and CD7, can be useful since such loss may occur in early MF while reactive infiltrates do not loose expression of these markers.[45,46] However, cases of benign CLI with loss of pan-T-cell markers have been reported; thus, an aberrant immunophenotype is not specific for early MF.[47,48,49] TCR-PCR is useful to differentiate the clonal versus polyclonal nature of a T-cell infiltrate.[50,51,52,53,54,55] However, in early MF, the relative mixture of neoplastic and reactive lymphocytes may yield false-negative results. Conversely, inflammatory dermatoses may demonstrate clonal rearrangements, particularly when performing PCR on sparse infiltrates (oligoclonality), and some inflammatory dermatoses are often clonal albeit exhibiting a benign clinical course (i.e., pityriasis lichenoides [PL], PPPD, medication reactions).[56]

Since the vast majority of patients presenting with early stage MF show an indolent course without disease progression[57,58] and given the aforementioned limitations of ancillary tests, a conservative approach is deemed preferable by the authors in the interpretation of clinically and/or histopathologically equivocal T-cell SDI in the absence of erythroderma. In this setting, it is recommended to explicitly acknowledge uncertainty in the pathology report and advise a “wait and see” approach, or perform a second biopsy either upon presentation or later in time. This strategy helps avoid over-diagnoses of lymphoma and permits a longitudinal clinical and histopathological analysis. If additional biopsies have been performed over time and the diagnosis remains unclear, TCR-PCR can be especially helpful. In particular, the detection of the same clone identified in biopsies from two separate sites is relatively specific for the diagnosis of early patch-MF.[59]

In patients with de novo erythroderma, however, a “wait and see” approach is not appropriate given that SS can be associated with a poor prognosis. Therefore, in this context, there is a need for a timely diagnosis. Patients should be thoroughly inspected and skin biopsy findings interpreted with caution as it is well documented that nonspecific findings are particularly common in biopsies from patients with SS. A comprehensive medication chart review is mandatory and peripheral blood studies to assess for circulating neoplastic lymphocytes. In most centers, this is assessed by a combination of flow cytometry and TCR-PCR.[10,11,12,13,14,15,16]

Superficial to deep-dermal, perivascular, and/or nodular natural killer or T-cell infiltrates

Cutaneous natural killer (NK)/T-cell infiltrates showing a superficial and deep perivascular or nodular pattern of infiltration and displaying attributes suggestive of lymphoma are also observed in dermatoses that range from common inflammatory diseases, such as persistent arthropod bite reactions, to rare but life-threatening forms of lymphoma such as PC aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma (PC-AECD8+ TCL) and extranodal NK/TCL (EN-NKTCL). Between such extremes are infrequent entities such as cutaneous lesions of connective tissue disease (CTD), actinic reticuloid, PL, and closer to the malignant pole are most histopathological subtypes of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) including Types A, D, and E. As for SDI, drug reactions enter the differential diagnosis within this category commonly displaying a combination of one or more patterns of infiltration [Table 2].[1,2,3,60]

Table 2.

Superficial to deep-dermal, perivascular and/or nodular natural killer/T-cell infiltrates

Clinically PC-AECD8+ TCL and EN-NKTCL typically affect middle-aged to older individuals and are characterized by generalized, rapidly growing plaques and tumors, which frequently ulcerate. They can appear in any topography, but EN-NKTCL has a predilection to involve the midline area of the face. Both have a poor prognosis with early extracutaneous dissemination and death from disease progression.[1,18,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] In contrast, all forms of LyP affect younger patients and appear as waxing and waning papules/small nodules typically clustered in one or two body segments, with no risk of disease progression and an excellent prognosis.[70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] Similar to LyP, PL affects young adults but tends to be disseminated to numerous body segments and display a self-limited course.[2,78,79,80,81] Established lesions of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE) are typically limited to sun-exposed skin and are easily recognizable either as atrophic scaly plaques with follicular dilation and pigmentary change (discoid LE) or annular to psoriasiform erythematous scaly plaques (subacute LE).[82] Actinic reticuloid, a rare disease that predominates in elderly men, manifests as extreme photosensitivity, erythema, pruritus, and lichenification, particularly in sun-exposed skin.[1,83,84,85] Finally, persistent arthropod bite reactions predominate in children and young adults as extremely pruritic papules or nodules which show a subacute course with eventual clearing [Figures 1 and 2].[1,86]

Histopathologically, inflammatory dermatoses herein most frequently exhibit evidence of their reactive nature (conspicuous interface alteration in PL and LE, spongiosis in PL and arthropod bite reactions, admixture of neutrophils or eosinophils in PL and arthropod bite reactions respectively, vasculitic changes in CTD and drug reactions).[1,2,79,81,82,86] However, a lack of such features and/or presence of attributes suggestive of lymphoma (epitheliotropism, vasculotropism, cellular pleomorphism) may be seen [Figure 4], but fortunately, such histopathologically atypical cases will often retain enough clinical characteristics to allow their recognition.[1,3,60]

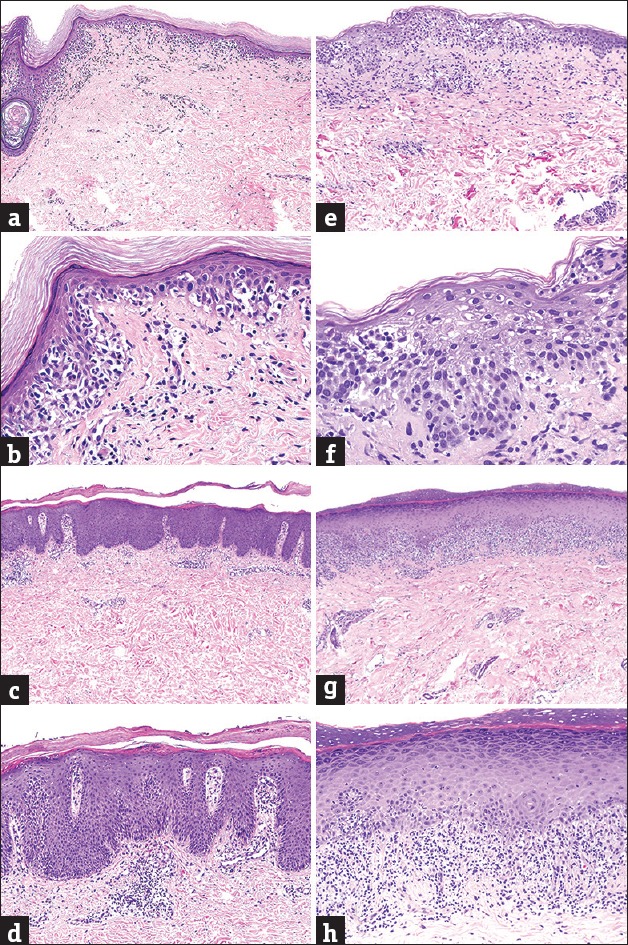

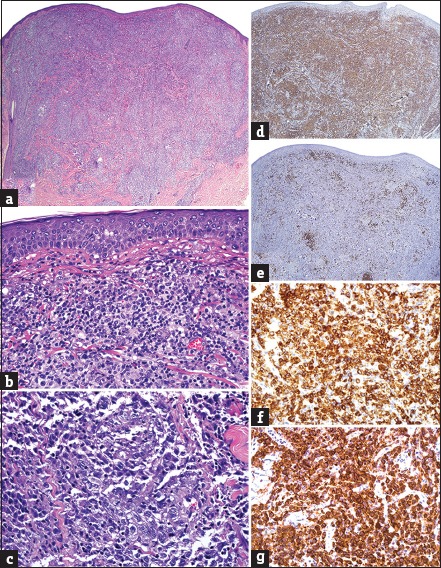

Figure 4.

(a) Superficial to deep-dermal, perivascular and/or nodular natural killer/T-cell infiltrate (H and E, ×20); (b) atypical lymphocytes with prominent angiocentricity/ angiodestruction in extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (H and E, ×400); (c) strong expression by neoplastic lymphocytes in extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (CD3 epsilon IHC, ×200); (d) strong immunoreactivity in extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (CD56 IHC, ×400); (e) strong nuclear expression of Epstein–Barr virus-encoded small RNA's in extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (EBER-ISH, ×400)

The use of IHC and molecular ancillary tests in this category is required when the clinical picture is suspicious for cytotoxic lymphomas (positivity for CD3ε, CD56, TIA-1, and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-encoded RNA in EN-NKTCL [Figure 4]; and positivity for CD8, βF1, and TIA-1 in PC-AECD8+TCL), and rarely necessary for the other entities where clinical information and histopathology are generally enough to render a specific diagnosis [Table 2].[1,63,64,67] Furthermore, certain reactive dermatoses within this group (mostly PL) may show positive TCR-PCR; thus, clinicopathological correlation remains the gold standard for diagnosis.[1,56,82]

Pan-dermal diffuse T-cell infiltrates

Dense and diffuse T-cell infiltrates occupying the totality or near-totality of the dermis have a narrower differential diagnosis [Table 3].[1,3,87] Within the benign pole, there are cases of drug-induced or idiopathic-T-cell pseudolymphoma, followed by clonal lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) that display an excellent prognosis but consensus is lacking regarding their true nature (i.e., lymphomatous vs. reactive), in particular small-medium pleomorphic CD4+ TCL (SMPTCL)[1,88,89,90,91,92] and indolent CD8+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder (ICD8+ CLPD).[93,94,95] PC-AECD8+TCL and EN-NKTCL, described under the former category, can also display this pattern of infiltration.[1,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] Among PC CD30+ LPDs, both LyP Type C and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) fall under this group, as does tumor stage MF.[73,74,75,76,77,96]

Table 3.

Pan-dermal diffuse T-cell infiltrates

As for previous categories, the clinical scenario helps to narrow the differential diagnosis. Both SMPTCL and ICD8+LPD are clinically characterized by a unilesional or oligolesional presentation with lesions usually <5 cm in diameter, and an indolent clinical course with a preferential distribution in the head and neck regions, although some cases of ICD8+ LPD may occur on distal extremities.[1,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95] PC ALCL also most frequently presents as a single nodule (or a few lesions restricted to a single region) but tends to ulcerate and occur on the extremities. LyP Type C, histopathologically identical to PC-ALCL, often affects younger patients and shows the classical chronic, recurrent, and self-healing course.[74,75,76,77,96] In contrast, patients with tumor stage MF have a history or clinical background of the typical patches/plaques of MF distributed in sun-shielded skin or less commonly erythroderma [Figures 1 and 2].[17,18,19,20]

Histopathologically, the cell size is additionally helpful for distinguishing the entities herein. A stark predominance of large cells, often representing over 75% of the infiltrate, is most commonly indicative of ALCL or LyP Type C; distinguishing these two closely-related entities relies entirely upon their clinical scenario after confirming (by IHC) the CD30+ nature of neoplastic lymphocytes.[74,75,76,77,96] In some cases, tumors of MF can also be composed of large cells, in particular in the context of large cell transformation, which is a phenomenon associated with a poor prognosis and is characterized by the presence of over 25% large cells.[97] In contrast, SMPTCL, ICD8+ LPD, and some cases of tumor stage MF are comprised by a predominance of small and medium lymphocytes with <30% of their cellularity being of the large size [Figure 5].[1,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]

Figure 5.

(a) Pan-dermal diffuse T-cell infiltrate (H and E, ×20); (b) mixture of small and medium, nonepidermotropic lymphocytes in small-medium pleomorphic CD4+ T-cell lymphoma (H and E, ×200); (c) large atypical cells with prominent nucleoli in anaplastic large cell lymphoma (H and E, ×400); (d) strong expression amongst small and medium T-cells in small-medium pleomorphic CD4+ T-cell lymphoma (CD4 IHC, ×20); (e) positivity restricted to admixed reactive B-cells in small-medium pleomorphic CD4+ T-cell lymphoma (CD20 IHC, ×20); (f) strong expression by sheets of large cells in anaplastic large cell lymphoma (CD30 IHC, ×400); (g) strong immunoreactivity by large cells in extracutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALK-1 IHC, ×400)

IHC is required when approaching these infiltrates. Tumor stage MF and SMPTCL show a T-helper (CD4+) cell predominance and occasionally lose pan-T-cell antigens. SMPTCL and cases of pseudolymphoma more commonly show a conspicuous background of reactive B-cells and strong expression of follicular helper T-cell markers (programmed death-1, CXCL13, etc.,) among infiltrating T-cells. However, interpretative caution is required as expression of follicular helper T-cell markers is now known to be prevalent among many PCL (including MF) and some reactive dermatoses and is not restricted to angioimmunoblastic TCL and SMPTCL.[98,99,100] CD30 expression, positive in the majority of cells in ALCL and LyP Type C, can also be found in some examples of tumor stage MF. In these latter entities, the percentage of CD30 labeling cells is typically limited to a minority of lymphocytes (<30%). Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1 (ALK-1), an antibody indicative of the 2;5 chromosomal translocation, is present in most nodal cases of ALK-positive ALCL and usually not in PC-ALCL and LyP. It should be noted that lack of labeling with ALK-1 does not exclude secondary cutaneous involvement of nodal lymphoma since some forms of nodal ALCL are ALK-1 negative. Therefore, any patient diagnosed with ALCL is required to undergo complete staging to exclude extracutaneous disease.[97] Predominance of small and medium CD8+ lymphocytes is the hallmark of ICD8+ CLPD.[95] However, some cases of MF may show an aberrant immunophenotype with a CD8+ CD4− or CD4/CD8 co-expression, thus stressing the need for clinical correlation.[100,101]

TCR-PCR in most entities described above will yield monoclonal results. Nonetheless, ordering such test is debatable since these are usually diagnosed without difficulty after compiling clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical information. Molecular studies in SMPTCL, however, have reported polyclonality in up to 40% of cases, reigniting the discussion about its true neoplastic versus reactive nature, and reinforcing the notion that what was previously designated as “pseudolymphomatous folliculitis” may in fact be the same disease as SMPTCL.[91,102]

Panniculitic T-cell infiltrates

Among predominantly lymphocytic panniculitis [Table 4], considerable overlap is seen especially between lupus panniculitis/lupus profundus (lupus erythematosus panniculitis [LEP]) and subcutaneous panniculitis-like TCL (SPLTCL).[1,103,104,105] Moreover, gamma-delta TCL (GDTCL) needs to be carefully excluded in any worrisome looking panniculitic infiltrate, given the poor prognosis it conveys and the high risk of potentially life-threatening secondary hemophagocytic syndrome.[106,107,108,109,110]

Table 4.

Panniculitic T-cell infiltrate

Distinction between LEP and SPLTCL may be particularly challenging; both occur most commonly in adult women as subcutaneous erythematous nodules/plaques, mainly in the extremities and trunk (albeit facial involvement is more common in LEP) and are characterized histopathologically by a lobular lymphocytic infiltrate.[1,103,104,105,111,112] Relying on serological tests to differentiate these entities is not particularly helpful, since only a minority of patients with LEP shows serological aberrations indicative of LE, and if present they are not unequivocal evidence of the reactive nature of the process.[1,103,113] Furthermore, rare clear-cut cases of LEP eventually progressing to SPLTCL have been described, suggesting that these may represent two poles within a spectrum of disease rather than independent entities [Figures 1 and 2].[113,114]

Notwithstanding these asseverations, several histopathological features have been proposed as helpful in favoring LEP over SPLTCL, including presence of conspicuous interface changes (50% of LEP cases), broadened fibrotic septa, hyalinized fat necrosis, and lymphoid follicles with or without germinal centers (GC).[111,112,115,116] As opposed to LEP, where a relative mixture of B-cells, plasma cells, and histiocytes is commonly seen on the background of the CD8 predominant infiltrate,[112,117] SPLTCL is composed mainly of CD8+ lymphocytes.[118,119] Neoplastic lymphocytes in SPLTCL are medium to large pleomorphic cells, have pronounced tropism for adipocytes, and commonly display circumferential “rimming” around such cells. This phenomenon can be observed in LEP, but constituent cells comprise a mixture of inflammatory cells along with small CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells, in contrast to the almost exclusively CD8+ rimming seen in SPLTCL.[120] Furthermore, in SPLTCL, rimming lymphocytes show a high Ki-67 labeling index as opposed to LEP where the lymphocytes that rim adipocytes display a low to moderate proliferation rate as assessed by Ki-67 IHC [Figure 6].[1,103]

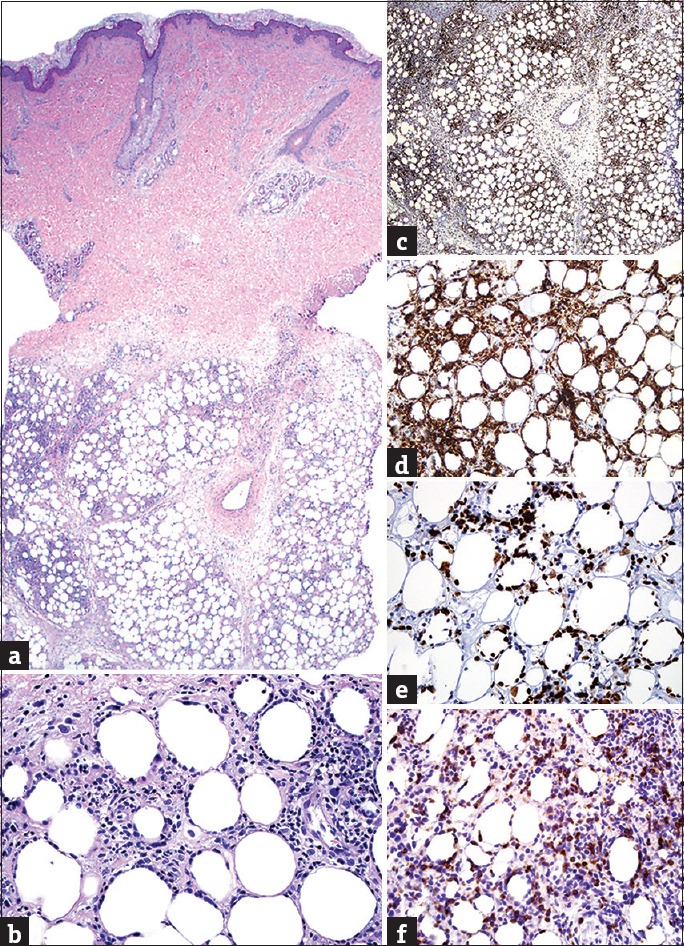

Figure 6.

(a) Panniculitic T-cell infiltrate (H and E, ×20); (b) rimming of adipocytes by atypical lymphocytes in subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (H and E, ×400); (c) prominent expression in subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (βF1 IHC, ×20); (d) strong immunoreactivity in subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (CD8 IHC, ×400); (e) high labeling index, especially among rimming lymphocytes in subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (Ki-67 IHC, ×400); (f) strong nuclear expression in gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma (TCRγ IHC, ×400)

GDTCL is characterized by rapid-onset of disease, generalized skin involvement, and a polymorphous appearance with rapidly growing patches, plaques, and tumors, all commonly present from the onset. Lesions commonly ulcerate (unlike LEP or SPLTCL) and may involve mucosal sites.[106,108,110] As in LEP, GDTCL may show noticeable interface changes and/or papillary dermal edema. However, GDTCL typically also demonstrates prominent epidermotropism along with angiocentricity/angiodestruction, which are features typically absent in LEP. Furthermore, GDTCL is mainly composed of a double negative (CD4−, CD8−) CLI (CD4−, CD8+ in approximately 40% of cases) with frequent expression of CD56 and cytotoxic proteins. Modern IHC easily discriminates the alpha-beta versus gamma-delta lineage of CLI; thus, screening for βF1 and GM1, the former present in LEP/SPLTCL and the latter in GDTCL, should be performed on every panniculitic lymphoma [Figure 6].[108,110,120,121,122]

Both SPLTCL and GDTCL are characterized by a clonal TCR-PCR.[110] Unfortunately, genotyping may be misleading if used to differentiate LEP from SPLTC since the former may show clonal rearrangements in a small proportion of cases.[113]

Small-cell predominant, B-cell infiltrates

Nodular or diffuse CLIs composed predominantly of small B-cells are the hallmark of B-cell pseudolymphoma (CLH) and low-grade PC-B-cell lymphoma (BCL), i.e., marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) and follicle center lymphoma (FCL) [Table 5].[4,123,124] As for TCL, BCL originating from extracutaneous sites may disseminate to the skin and display a small-cell pattern of infiltration, most commonly seen in follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Some of these entities can be histopathologically indistinguishable from their PC counterparts, in particular, FCL and MZL.[124,125,126,127,128,129,130] Therefore, a staging evaluation is mandatory after a diagnosis of BCL detected in the skin to exclude secondary cutaneous involvement.

Table 5.

Small-cell predominant, B-cell infiltrate

The differential diagnosis between indolent forms of PC-BCL and CLH can be challenging. CLH is defined as a benign reactive CLI, likely arising from continued antigenic stimulation. Its former nomenclature varied (cutaneous pseudolymphoma, lymphocytoma cutis, lymphadenosis benigna cutis, etc.,) and the term CLH has been used by some authors to include both B- and T-cell cutaneous pseudolymphomas.[131] In an effort to avoid confusion, the authors herein restrict the term CLH for cutaneous pseudolymphomas composed predominantly of small B-cells.

CLH shows striking clinical similarities to low-grade PC-BCL and identifying the antigenic trigger is rarely possible. Furthermore, relying on the identification of a specific trigger to favor a diagnosis of CLH versus MZL, or FCL is not particularly helpful as bona fide low-grade PC-BCL has also been described following chronic antigenic stimulation, particularly in response to Borrelia infection.[132,133] Both CLH, MZL, and FCL appear as single or multiple, red to violaceous, slow-growing cutaneous nodules, predominantly affecting face, trunk, or upper extremities, with only slight differences in their clinical morphology and topographic predilection (perilesional annular erythema and scalp or forehead involvement favoring FCL), thus making clinical features rarely discriminatory [Figure 2]. CLH may affect all ages while both FCL and MZL most commonly occur in middle-aged to older individuals.[133,134,135] In contrast to PC-BCL, CLH by definition follows a self-limited course and/or a prompt resolution after discontinuation/treatment of the inciting agent. However, identifying the responsible agent(s) may prove impossible, and in some cases, a longitudinal follow-up of the patient is required to achieve a definitive diagnosis.[1,136]

Common histopathological features in CLH, MZL, and FCL are the presence of a nonepidermotropic, nodular/diffuse, bottom-heavy or top-heavy CLI, with or without reactive follicles (GC).[137,138,139] Both CLH and low-grade PC-BCL may show a monotonous or mixed cellular infiltrate, with admixed eosinophils, histiocytes, and/or neutrophils. However, when inflammatory cells are present in conspicuous amounts or accompanied by reactive epidermal changes, a diagnosis of CLH is favored on morphological grounds.[131] By contrast, confluent sheets of plasma cells or lymphoplasmacytoid cells (sometimes with intranuclear inclusions) commonly distributed at the margins of the infiltrate, coupled with an expansion of pale-staining, medium-sized cells with indented nuclei (marginal zone cells or centrocyte-like cells), which surround aggregates of small and dark-staining lymphocytes, favor a diagnosis of MZL.[133] In FCL, neoplastic cells are chiefly centrocytes, admixed with a few centroblasts, small monotonous lymphocytes, inflammatory cells and occasional immunoblasts. When lymphoid follicles are present, aberrancies in the architecture of GC (variable sizes and shapes, follicular confluence, reduced/absent mantle zone, lack of polarization, paucity of tangible body macrophages) and aggregates of centrocytes and/or centroblasts outside or between GC favor the diagnosis of FCL [Figure 7].[135,140]

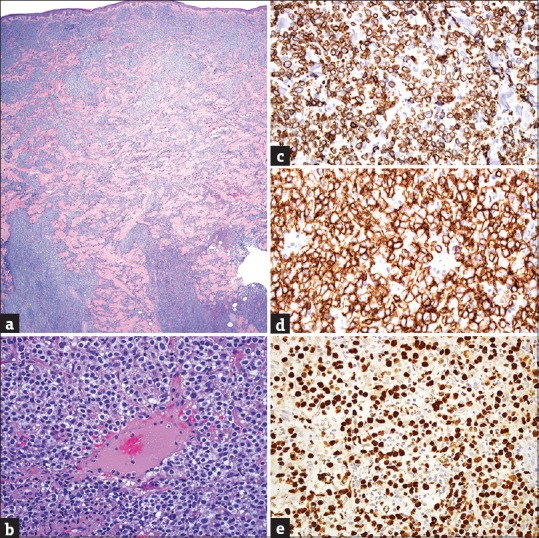

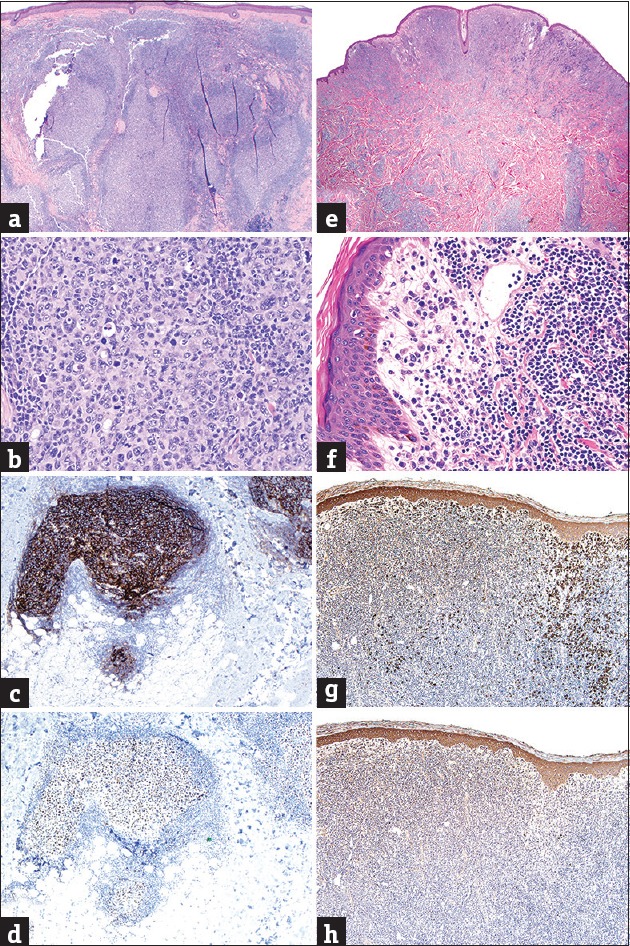

Figure 7.

(a) Small-cell predominant B-cell infiltrate with germinal centers in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (H and E, ×20); (b) tingible body macrophages in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (H and E, ×200); (c) follicular-dendritic networks in germinal centers of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (CD21 IHC, ×40); (d) immunoreactivity inside a germinal center in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (BCL6 IHC, ×40); (e) superficial and deep small-cell predominant B-cell infiltrate in marginal zone lymphoma (note periadnexal accentuation) (H and E, ×20); (f) peripheral plasma cells and cleaved lymphocytes in marginal zone lymphoma (H and E, ×400); (g) Kappa immunoglobulin light chain restriction in marginal zone lymphoma (Kappa ISH, ×20); (h) absence of lambda expression in marginal zone lymphoma (Lambda ISH, ×20)

IHC analyses are required to define the phenotype of small-cell predominant, B-cell infiltrates. A mixture of T-cells amid the predominantly B-cell infiltrate is commonly encountered in both CLH and low-grade PC-BCL. Nonetheless, a near-equal mixture is more common to CLH while MZL and FCL typically display a ratio of neoplastic B-cells versus reactive T-cells ≥3:1.[137] In MZL, the most important IHC criterion for diagnosis is monoclonal restriction of immunoglobulin light chains (either k or λ) in lymphoplasmacytoid and plasma cells; this finding is absent in CLH and FCL and can more reliably be addressed by means of in situ hybridization (ISH).[133,141] Neoplastic lymphocytes in FCL show reactivity with GC-cell markers (BCL6, CD10) and such antibodies often highlight the aberrant localization of clusters of centrocytes/centroblasts outside GC. This finding can be substantiated with CD21, a marker of dendritic reticulum cells, useful in identifying the presence of often-indiscernible residual follicles; it also highlights their normal versus abnormal architecture. When attempting to differentiate FCL with a follicular pattern from CLH, the proliferation rate within GC may be additionally evaluated with Ki-67, being typically very high within reactive GC of CLH (>90%) and pathologically reduced (<50%) in approximately half the cases of FCL.[135,140,142] In contrast to extracutaneous FCL, neoplastic B-cells in PC-FCL rarely express BCL2 since such cases typically lack the chromosomal translocation t(14:18). Expression of this protein should be interpreted with caution since reactive T-cells are commonly BCL2+. Nonetheless, its true co-expression by BCL6 or CD10+ B-cells is essentially diagnostic of lymphoma incompatible with CLH and should trigger an evaluation for extracutaneous FCL. Typically, when BCL2 is expressed in FCL in the skin, the FCL represents extracutaneous involvement of a systemic lymphoma. Nevertheless, there are rare cases of PC-FCL that express BCL2.[135,140,143]

Molecular genotyping of FCL reveals a monoclonal rearrangement of immunoglobulin heavy chain genes (IgH) in over 50% of cases;[135] this contrasts with typical polyclonal results in IgH gene rearrangement studies for MZL,[144,145] thus having to rely on light chain restriction analysis to confirm the monoclonal nature of B-cells in this entity.[1,135] CLH shows a nonrestricted light chain expression and the vast majority of cases polyclonal PCR bands upon IgH rearrangement studies. Nonetheless, a small proportion of archetypical CLH (approx 10%) displays monoclonality. For such cases, some authors favor the nomenclature of “clonal CLH,” acknowledging the possibility of progression into bona fide low-grade PC-BCL and the need for close clinical follow-up.[146,147,148,149,150]

Large-cell predominant, B-cell infiltrates

Diffuse dermal and/or subcutaneous infiltrates, composed mainly of large B-cells, usually indicate lymphoma, either primary to the skin [Table 6] or originating at extracutaneous sites. The PC archetype within this category is diffuse large BCL (DLBCL) of the leg (DLBCL-LT).[151] However, FCL displaying an absence of GC and a diffuse or nodular pattern of infiltration may occasionally show predominance of large cells and thus, must be considered in the differential diagnosis together with rare examples of DLBCL associated with immunosuppression and EBV infection. Distinguishing these categories is paramount for prognostic and therapeutic implications; while clinical findings are important to narrow the differential diagnosis, thorough cytomorphological and immunophenotypical analyses are indispensable.[1,152]

Table 6.

Large-cell predominant, B-cell infiltrate

DLBCL most often occurs in elderly patients as a rapidly growing tumor on the lower extremities (DLBCL-LT),[152,153] or elsewhere in immunocompromised patients, often in association with genomic EBV integration into the nuclei of neoplastic lymphocytes (DLBCL-not otherwise specified [NOS]).[154,155] FCL usually affects younger patients, with slow-growing clustered nodules/plaques in the scalp or upper back, often-displaying peripheral erythema [Figure 2].[134,135,140]

The morphology of infiltrating lymphocytes aids in narrowing the differential diagnosis. DLBCL chiefly displays large cells with prominent central nucleoli (immunoblasts) while the diffuse variant of FCL is composed of medium-sized lymphocytes with cleaved nuclei (centrocytes) and/or large cells with peripheral nucleoli (centroblasts) with a scarcity of immunoblasts [Figure 8]. In some cases, a mixture of both immunoblasts and centrocyte/centroblasts is present, and thus, it may be impossible to define the predominant cellular morphology. Such cases are often nonclassifiable and best fit with DLBCL-NOS if IHC fails to discern the origin of neoplastic B-cells.[134,135,140,152]

Figure 8.

(a) Pandermal large-cell predominant B-cell infiltrate (H and E, ×20); (b) medium-sized cleaved lymphocytes (centrocytes) in follicle center lymphoma (H and E, ×400); (c), large round cells with central nucleoli (immunoblasts) in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (H and E, ×400); (d) expression in follicle center lymphoma (CD20 IHC, ×20); (e) immunoreactivity by most cells in follicle center lymphoma (BCL6 IHC, ×20); (f) atypical follicular dendritic networks in follicle center lymphoma (CD21 IHC, ×20); (g) expression by neoplastic cells in an ulcerated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (CD20 IHC, ×20); (h) expression by most cells in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (BCL2 IHC, ×20); (i) high percentage (>50%) of nuclear immunoreactivity in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (MUM1 IHC, ×20)

All lymphomas in this category display an abundance of B-cells. However, a background of small reactive T-cells is frequently observed; identifying such T-cells is important since BCL2 (normally expressed in reactive T-cells) is invariably used as a tool in their subclassification.[134,152,156] As mentioned, neoplastic B-cells in most PC-FCL are BCL6+/BCL2− with a relatively low Ki-67 proliferation rate. Furthermore, the MUM1 expression is absent or present in a minority of tumor cells, and CD21 may occasionally highlight residual follicular dendritic networks.[135,140,142] By contrast, DLBCL-LT is strongly BCL2+, IgM+, MUM1+ (in at least 30% of the infiltrate), and the proliferation index is markedly high. GC B-cell markers are occasionally present, but remnants of CD21+ follicular dendritic cells are absent.[156,157] Cases displaying a mixture of morphological or immunophenotypical features of both FCL and DLBCL-LT are currently classified as DLBCL-NOS; in these cases, ISH screening for EBV-encoded RNA may clarify the diagnosis, particularly in elderly or immunocompromised patients.[154,155]

Monoclonal rearrangements of IgH genes are most often identifiable within the lymphomas herein. However, their diagnostic value is limited given the lack of inflammatory imitators within this category. Nonetheless, the presence or absence of specific genomic aberrations and or mutations is growingly recognized, among extracutaneous DLBCL as potentially holding relevant prognostic and therapeutic implications.[158] Their relevance in PC-DLBCL is still unclear, and further studies to address their utility are warranted.

Conclusions

CLIs are common to numerous neoplastic and inflammatory dermatoses and encompass some of the most challenging entities in dermatopathology. Immunophenotypic and molecular techniques have improved their proper classification. However, due to specificity and sensitivity limitations of ancillary techniques, the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphomas and simulants continues to rest on clinicopathological correlation with IHC and clonality studies serving as adjunctive tools in some cases. In equivocal or challenging cases, acknowledging uncertainty is important; these cases may ultimately benefit from referral to dedicated cutaneous lymphoma centers for expert evaluation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Authors provide a practical approach to CLIs based on six morphologic and immunophenotypic histopathological patterns.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Judith Dominguez-Cherit M. D. and Juan Ruiz-Matta M. D. for their contributions with clinical images and John G. Williams for his technical advice on “image processing.”

References

- 1.Cerroni L. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014. Skin Lymphoma: The Illustrated Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, Kinney MC, Swerdlow SM, Willemze R, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma: Report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology workshop. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:536–51. doi: 10.1309/AJCPX4BXTP2QBRKO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laban É, Beylot-Barry M, Ortonne N, Battistella M, Carlotti A, de Muret A, et al. Cutaneous lymphoproliferations: Proposal for the use of diagnostic algorithms based on 2760 cases of cutaneous lymphoproliferations taken from the INCa networks (LYMPHOPATH and GFELC) over a two-year period. Ann Pathol. 2015;35:131–47. doi: 10.1016/j.annpat.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, Swerdlow SH, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magro CM, Crowson AN. Drug-induced immune dysregulation as a cause of atypical cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates: A hypothesis. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:125–32. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90365-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magro CM, Crowson AN, Kovatich AJ, Burns F. Drug-induced reversible lymphoid dyscrasia: A clonal lymphomatoid dermatitis of memory and activated T cells. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:119–29. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, Vonderheid E, Haeffner AC, Stevens S, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotta AC, Cintra ML, de Souza EM, Magna LA, Vassallo J. Reassessment of diagnostic criteria in cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates. Sao Paulo Med J. 2004;122:161–5. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802004000400006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arps DP, Chen S, Fullen DR, Hristov AC. Selected inflammatory imitators of mycosis fungoides: Histologic features and utility of ancillary studies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1319–27. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0298-CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olek-Hrab K, Silny W. Diagnostics in mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2013;19:72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moriarty B, Whittaker S. Diagnosis, prognosis and management of erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2015;8:159–71. doi: 10.1586/17474086.2015.984681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernengo MG, Quaglino P. Erythrodermic CTCL: Updated clues to diagnosis and treatment. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2012;147:533–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubica AW, Davis MD, Weaver AL, Killian JM, Pittelkow MR. Sézary syndrome: A study of 176 patients at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1189–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mistry N, Gupta A, Alavi A, Sibbald RG. A review of the diagnosis and management of erythroderma (generalized red skin) Adv Skin Wound Care. 2015;28:228–36. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000463573.40637.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen EA, Rook AH, Zic J, Kim Y, Porcu P, Querfeld C, et al. Sézary syndrome: Immunopathogenesis, literature review of therapeutic options, and recommendations for therapy by the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium (USCLC) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:352–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, Willemze R, Kim Y, Knobler R, et al. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: A proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Blood. 2007;110:1713–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-055749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: An updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933–48. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Kerl K. Cutaneous lymphomas: An update. Part 1: T-cell and natural killer/t-cell lymphomas and related conditions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:105–23. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318289b1db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamashita T, Abbade LP, Marques ME, Marques SA. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: Clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical review and update. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:817–28. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962012000600001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho-Vega JH, Tschen JA, Duvic M, Vega F. Early-stage mycosis fungoides variants: Case-based review. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010;14:369–85. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez JL, Ackerman AB. The patch stage of mycosis fungoides. Criteria for histologic diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:5–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krajewski AS, Myskow MW, Cachia PG, Salter DM, Sheehan T, Dewar AE. T-cell lymphoma: Morphology, immunophenotype and clinical features. Histopathology. 1988;13:19–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1988.tb02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoppe RT, Wood GS, Abel EA. Mycosis fungoides and the Sézary syndrome: Pathology, staging, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 1990;14:293–371. doi: 10.1016/0147-0272(90)90018-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abel EA, Wood GS, Hoppe RT. Mycosis fungoides: Clinical and histologic features, staging, evaluation, and approach to treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 1993;43:93–115. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.43.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smoller BR, Santucci M, Wood GS, Whittaker SJ. Histopathology and genetics of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2003;17:1277–311. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(03)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith BD, Wilson LD. Management of mycosis fungoides. Part 1. Diagnosis, staging, and prognosis Oncology (Williston Park) 2003;17:1281–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kazakov DV, Burg G, Kempf W. Clinicopathological spectrum of mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:397–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barr RJ, Young EM., Jr Psoriasiform and related papulosquamous disorders. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:412–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1985.tb00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Champion RH. Psoriasis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:1693–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6537.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox BJ, Odom RB. Papulosquamous diseases: A review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:597–624. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christophers E, Mrowietz U. The inflammatory infiltrate in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:131–5. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)93819-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prens E, Debets R, Hegmans J. T lymphocytes in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:115–29. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)93818-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalton SR, Chandler WM, Abuzeid M, Hossler EW, Ferringer T, Elston DM, et al. Eosinophils in mycosis fungoides: An uncommon finding in the patch and plaque stages. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:586–91. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31823d921b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Candiago E, Marocolo D, Manganoni MA, Leali C, Facchetti F. Nonlymphoid intraepidermal mononuclear cell collections (pseudo-Pautrier abscesses): A morphologic and immunophenotypical characterization. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:1–6. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200002000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Houck G, Saeed S, Stevens GL, Morgan MB. Eczema and the spongiotic dermatoses: A histologic and pathogenic update. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2004;23:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(03)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LeBoit PE, Epstein BA. A vase-like shape characterizes the epidermal-mononuclear cell collections seen in spongiotic dermatitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:612–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ackerman AB, Breza TS, Capland L. Spongiotic simulants of mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:218–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guitart J, Peduto M, Caro WA, Roenigk HH. Lichenoid changes in mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(3 Pt 1):417–22. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Hoqail IA, Crawford RI. Benign lichenoid keratoses with histologic features of mycosis fungoides: Clinicopathologic description of a clinically significant histologic pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:291–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toro JR, Sander CA, LeBoit PE. Persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis and mycosis fungoides: Simulant, precursor, or both?. A study by light microscopy and molecular methods. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:108–18. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199704000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crowson AN, Magro CM, Zahorchak R. Atypical pigmentary purpura: A clinical, histopathologic, and genotypic study. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1004–12. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh NM, Prokopetz R, Tron VA, Sawyer DM, Watters AK, Murray S, et al. Histopathology in erythroderma: Review of a series of cases by multiple observers. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:419–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1994.tb00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ming M, LeBoit PE. Can dermatopathologists reliably make the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides?. If not, who can. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:543–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.4.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zackheim HS, McCalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: The great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914–8. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.124696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michie SA, Abel EA, Hoppe RT, Warnke RA, Wood GS. Discordant expression of antigens between intraepidermal and intradermal T cells in mycosis fungoides. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:1447–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knowles DM. Immunophenotypic and antigen receptor gene rearrangement analysis in T cell neoplasia. Am J Pathol. 1989;134:761–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moll M, Reinhold U, Kukel S, Abken H, Müller R, Oltermann I, et al. CD7-negative helper T cells accumulate in inflammatory skin lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:328–32. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12371791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu L, Abken H, Pföhler C, Rappl G, Tilgen W, Reinhold U. Accumulation of CD4+CD7- T cells in inflammatory skin lesions: Evidence for preferential adhesion to vascular endothelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:94–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alaibac M, Pigozzi B, Belloni-Fortina A, Michelotto A, Saponeri A, Peserico A. CD7 expression in reactive and malignant human skin T-lymphocytes. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2707–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lessin SR, Rook AH, Rovera G. Molecular diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: Polymerase chain reaction amplification of T-cell antigen receptor beta-chain gene rearrangements. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:299–302. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12465108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volkenandt M, Soyer HP, Kerl H, Bertino JR. Development of a highly specific and sensitive molecular probe for detection of cutaneous lymphoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:137–40. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12479308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lorenzen J, Jux G, Zhao-Höhn M, Klöckner A, Fischer R, Hansmann ML. Detection of T-cell clonality in paraffin-embedded tissues. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1994;3:93–9. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199406000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mielke V, Staib G, Boehncke WH, Duller B, Sterry W. Clonal disease in early cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:351–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood GS, Haeffner A, Dummer R, Crooks CF. Molecular biology techniques for the diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:231–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terhune MH, Cooper KD. Gene rearrangements and T-cell lymphomas. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1484–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holm N, Flaig MJ, Yazdi AS, Sander CA. The value of molecular analysis by PCR in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:447–52. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim YH, Jensen RA, Watanabe GL, Varghese A, Hoppe RT. Clinical stage IA (limited patch and plaque) mycosis fungoides. A long-term outcome analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1309–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim YH, Liu HL, Mraz-Gernhard S, Varghese A, Hoppe RT. Long-term outcome of 525 patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: Clinical prognostic factors and risk for disease progression. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:857–66. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.7.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thurber SE, Zhang B, Kim YH, Schrijver I, Zehnder J, Kohler S. T-cell clonality analysis in biopsy specimens from two different skin sites shows high specificity in the diagnosis of patients with suggested mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:782–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu V, McKee PH. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: Approach for the surgical pathologist: Recent advances and clarification of confused issues. Adv Anat Pathol. 2002;9:79–100. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berti E, Tomasini D, Vermeer MH, Meijer CJ, Alessi E, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous CD8-positive epidermotropic cytotoxic T cell lymphomas. A distinct clinicopathological entity with an aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:483–92. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65144-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Ortiz-Romero PL, Monsalvez V, Tomás IE, Almagro M, Sevilla A, et al. TCR-g expression in primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:375–84. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318275d1a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kempf W, Rozati S, Kerl K, French LE, Dummer R. Cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas, unspecified/NOS and rare subtypes: A heterogeneous group of challenging cutaneous lymphomas. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2012;147:553–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, Salah E. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+T-cell lymphoma: Proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:748–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gormley RH, Hess SD, Anand D, Junkins-Hopkins J, Rook AH, Kim EJ. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:300–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chuang SS, Ko YH. Cutaneous nonmycotic T- and natural killer/T-cell lymphomas: Diagnostic challenges and dilemmas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:724–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Willemze R. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: Epidemiology, etiology, and classification. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44(Suppl 3):S49–54. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001623766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Win KT, Liau JY, Chen BJ, Takata K, Chen CY, Li CC, et al. Primary cutaneous extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma misdiagnosed as peripheral T-cell lymphoma: The importance of consultation/referral and inclusion of EBV in situ hybridization for diagnosis. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2016;24:105–11. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kato N, Yasukawa K, Onozuka T, Kikuta H. Nasal and nasal-type T/NK-cell lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5 Pt 2):850–6. doi: 10.1053/jd.1999.v40.a94087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Plaza JA, Feldman AL, Magro C. Cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders with CD8 expression: A clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:236–47. doi: 10.1111/cup.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saggini A, Gulia A, Argenyi Z, Fink-Puches R, Lissia A, Magaña M, et al. A variant of lymphomatoid papulosis simulating primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma. Description of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1168–75. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e75356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kempf W, Mitteldorf C. Cutaneous lymphomas: New entities and rare variants. Pathologe. 2015;36:62–9. doi: 10.1007/s00292-014-2017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martinez-Escala ME, Sidiropoulos M, Deonizio J, Gerami P, Kadin ME, Guitart J. gd T-cell-rich variants of pityriasis lichenoides and lymphomatoid papulosis: Benign cutaneous disorders to be distinguished from aggressive cutaneous gd T-cell lymphomas. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:372–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bertolotti A, Pham-Ledard AL, Vergier B, Parrens M, Bedane C, Beylot-Barry M. Lymphomatoid papulosis type D: An aggressive histology for an indolent disease. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1157–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Calzado-Villarreal L, Polo-Rodríguez I, Ortiz-Romero PL. Primary cutaneous CD30+lymphoproliferative disorders. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:119–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guitart J, Querfeld C. Cutaneous CD30 lymphoproliferative disorders and similar conditions: A clinical and pathologic prospective on a complex issue. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2009;26:131–40. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kempf W. CD30+lymphoproliferative disorders: Histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(Suppl 1):58–70. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, Kihiczak G, Lambert WC. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: A disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khachemoune A, Blyumin ML. Pityriasis lichenoides: Pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:29–36. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200708010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bowers S, Warshaw EM. Pityriasis lichenoides and its subtypes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:557–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Patel DG, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, Lambert WC. Pityriasis lichenoides. Cutis. 2000;65:17–20, 23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Magro CM, Crowson AN, Harrist TJ. Atypical lymphoid infiltrates arising in cutaneous lesions of connective tissue disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:446–55. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199710000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.O’Gorman SM, Murphy GM. Photoaggravated disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:385–98, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paek SY, Lim HW. Chronic actinic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:355. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Engin B, Songür A, Kutlubay Z, Serdaroglu S. Lymphocytic infiltrations of face. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hwong H, Jones D, Prieto VG, Schulz C, Duvic M. Persistent atypical lymphocytic hyperplasia following tick bite in a child: Report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:481–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.1861992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bekkenk MW, Vermeer MH, Jansen PM, van Marion AM, Canninga-van Dijk MR, Kluin PM, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphomas unspecified presenting in the skin: Analysis of prognostic factors in a group of 82 patients. Blood. 2003;102:2213–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodríguez Pinilla SM, Roncador G, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Mollejo M, García JF, Montes-Moreno S, et al. Primary cutaneous CD4+small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma expresses follicular T-cell markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:81–90. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31818e52fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grogg KL, Jung S, Erickson LA, McClure RF, Dogan A. Primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma: A clonal T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder with indolent behavior. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:708–15. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Williams VL, Torres-Cabala CA, Duvic M. Primary cutaneous small- to medium-sized CD4+pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma: A retrospective case series and review of the provisional cutaneous lymphoma category. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:389–401. doi: 10.2165/11590390-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Beltraminelli H, Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous CD4+small-/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma: A cutaneous nodular proliferation of pleomorphic T lymphocytes of undetermined significance?. A study of 136 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:317–22. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31819f19bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Leinweber B, Beltraminelli H, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Solitary small- to medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell nodules of undetermined significance: Clinical, histopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 26 cases. Dermatology. 2009;219:42–7. doi: 10.1159/000212118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wobser M, Petrella T, Kneitz H, Kerstan A, Goebeler M, Rosenwald A, et al. Extrafacial indolent CD8-positive cutaneous lymphoid proliferation with unusual symmetrical presentation involving both feet. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:955–61. doi: 10.1111/cup.12213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Swick BL, Baum CL, Venkat AP, Liu V. Indolent CD8+lymphoid proliferation of the ear: Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:209–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Suchak R, O’Connor S, McNamara C, Robson A. Indolent CD8-positive lymphoid proliferation on the face: Part of the spectrum of primary cutaneous small-/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma or a distinct entity? J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:977–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Massone C, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Kerl H, Cerroni L. The morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma: A histopathologic study on 66 biopsy specimens from 47 patients with report of rare variants. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:46–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vergier B, de Muret A, Beylot-Barry M, Vaillant L, Ekouevi D, Chene G, et al. Transformation of mycosis fungoides: Clinicopathological and prognostic features of 45 cases. French Study Group of Cutaneious Lymphomas. Blood. 2000;95:2212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ally MS, Prasad Hunasehally RY, Rodriguez-Justo M, Martin B, Verdolini R, Attard N, et al. Evaluation of follicular T-helper cells in primary cutaneous CD4+small/medium pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma and dermatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:1006–13. doi: 10.1111/cup.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cetinözman F, Jansen PM, Willemze R. Expression of programmed death-1 in primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous pseudo-T-cell lymphoma, and other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:109–16. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318230df87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bekel L, Chaby G, Lok C, Dadban A, Chatelain D, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma presenting as mycosis fungoides with a T-/null-cell phenotype: Report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1637–41. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hodak E, David M, Maron L, Aviram A, Kaganovsky E, Feinmesser M. CD4/CD8 double-negative epidermotropic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: An immunohistochemical variant of mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Arai E, Okubo H, Tsuchida T, Kitamura K, Katayama I. Pseudolymphomatous folliculitis: A clinicopathologic study of 15 cases of cutaneous pseudolymphoma with follicular invasion. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1313–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199911000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pincus LB, LeBoit PE, McCalmont TH, Ricci R, Buzio C, Fox LP, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma with overlapping clinicopathologic features of lupus erythematosus: Coexistence of 2 entities? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:520–6. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a84f32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Arps DP, Patel RM. Lupus profundus (panniculitis): A potential mimic of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1211–5. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0253-CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bosisio F, Boi S, Caputo V, Chiarelli C, Oliver F, Ricci R, et al. Lobular panniculitic infiltrates with overlapping histopathologic features of lupus panniculitis (lupus profundus) and subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma: A conceptual and practical dilemma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:206–11. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Salhany KE, Macon WR, Choi JK, Elenitsas R, Lessin SR, Felgar RE, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: Clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic analysis of alpha/beta and gamma/delta subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:881–93. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199807000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Berti E, Cerri A, Cavicchini S, Delia D, Soligo D, Alessi E, et al. Primary cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma presenting as disseminated pagetoid reticulosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:718–23. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12470953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, Sorbara L, Raffeld M, Steinberg SM, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3407–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, Berti E, Santucci M, Assaf C, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: Definition, classification, and prognostic factors: An EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group Study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111:838–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Guitart J, Weisenburger DD, Subtil A, Kim E, Wood G, Duvic M, et al. Cutaneous gd T-cell lymphomas: A spectrum of presentations with overlap with other cytotoxic lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1656–65. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826a5038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Crowson AN, Magro C. The cutaneous pathology of lupus erythematosus: A review. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:1–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.280101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Massone C, Kodama K, Salmhofer W, Abe R, Shimizu H, Parodi A, et al. Lupus erythematosus panniculitis (lupus profundus): Clinical, histopathological, and molecular analysis of nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:396–404. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Magro CM, Crowson AN, Kovatich AJ, Burns F. Lupus profundus, indeterminate lymphocytic lobular panniculitis and subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma: A spectrum of subcuticular T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:235–47. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028005235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hoque SR, Child FJ, Whittaker SJ, Ferreira S, Orchard G, Jenner K, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: A clinicopathological, immunophenotypic and molecular analysis of six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:516–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. Part II. Mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325–61. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ng PP, Tan SH, Tan T. Lupus erythematosus panniculitis: A clinicopathologic study. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:488–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liau JY, Chuang SS, Chu CY, Ku WH, Tsai JH, Shih TF. The presence of clusters of plasmacytoid dendritic cells is a helpful feature for differentiating lupus panniculitis from subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Histopathology. 2013;62:1057–66. doi: 10.1111/his.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cerroni L, Kerl H. Diagnostic immunohistology: Cutaneous lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18:64–70. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(99)80010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Cerroni L, Kerl H. The clinicopathologic spectrum of cytotoxic lymphomas of the skin. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:118–23. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(00)80008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lozzi GP, Massone C, Citarella L, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic lymphocytes: A histopathologic feature not restricted to subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:9–12. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000187933.87103.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Heald P, Buckley P, Gilliam A, Perez M, Knobler R, Kacinski B, et al. Correlations of unique clinical, immunotypic, and histologic findings in cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5 Pt 2):865–70. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70125-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ralfkiaer E, Wollf-Sneedorff A, Thomsen K, Geisler C, Vejlsgaard GL. T-cell receptor gamma delta-positive peripheral T-cell lymphomas presenting in the skin: A clinical, histological and immunophenotypic study. Exp Dermatol. 1992;1:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1992.tb00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cerroni L, Zöchling N, Pütz B, Kerl H. Infection by Borrelia burgdorferi and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:457–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1997.tb01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Franco R, Fernández-Vázquez A, Mollejo M, Cruz MA, Camacho FI, García JF, et al. Cutaneous presentation of follicular lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:913–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Guitart J. Rethinking primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma: Shifting the focus to the cause of the infiltrate. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:600–3. doi: 10.1111/cup.12509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bastion Y, Berger F, Bryon PA, Felman P, Ffrench M, Coiffier B. Follicular lymphomas: Assessment of prognostic factors in 127 patients followed for 10 years. Ann Oncol. 1991;2(Suppl 2):123–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-7305-4_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fink-Puches R, Zenahlik P, Bäck B, Smolle J, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: Applicability of current classification schemes (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, World Health Organization) based on clinicopathologic features observed in a large group of patients. Blood. 2002;99:800–5. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Senff NJ, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Willemze R. Results of bone marrow examination in 275 patients with histological features that suggest an indolent type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:52–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sen F, Medeiros LJ, Lu D, Jones D, Lai R, Katz R, et al. Mantle cell lymphoma involving skin: Cutaneous lesions may be the first manifestation of disease and tumors often have blastoid cytologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1312–8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Geerts ML, Busschots AM. Mantle-cell lymphomas of the skin. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:409–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bergman R, Khamaysi K, Khamaysi Z, Ben Arie Y. A study of histologic and immunophenotypical staining patterns in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:112–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Picken RN, Strle F, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Maraspin V, Lotric-Furlan S, Cimperman J, et al. Molecular subtyping of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates from five patients with solitary lymphocytoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:92–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cerroni L, Signoretti S, Höfler G, Annessi G, Pütz B, Lackinger E, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: A recently described entity of low-grade malignant cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1307–15. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199711000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kerl H, Kodama K, Cerroni L. Diagnostic principles and new developments in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;34:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Leinweber B, Colli C, Chott A, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Differential diagnosis of cutaneous infiltrates of B lymphocytes with follicular growth pattern. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:4–13. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, Chott A, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated lymphocytoma cutis: Clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Baldassano MF, Bailey EM, Ferry JA, Harris NL, Duncan LM. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia and cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma: Comparison of morphologic and immunophenotypic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:88–96. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Arai E, Shimizu M, Hirose T. A review of 55 cases of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: Reassessment of the histopathologic findings leading to reclassification of 4 lesions as cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and 19 as pseudolymphomatous folliculitis. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:505–11. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rijlaarsdam JU, Meijer CJ, Willemze R. Differentiation between lymphadenosis benigna cutis and primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphomas. A comparative clinicopathologic study of 57 patients. Cancer. 1990;65:2301–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900515)65:10<2301::aid-cncr2820651023>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kim BK, Surti U, Pandya A, Cohen J, Rabkin MS, Swerdlow SH. Clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular cytogenetic fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of primary and secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:69–82. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146015.22624.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Schafernak KT, Variakojis D, Goolsby CL, Tucker RM, Martínez-Escala ME, Smith FA, et al. Clonality assessment of cutaneous B-cell lymphoid proliferations: A comparison of flow cytometry immunophenotyping, molecular studies, and immunohistochemistry/in situ hybridization and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:781–95. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bryant RJ, Banks PM, O’Malley DP. Ki67 staining pattern as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of lymphoproliferative disorders. Histopathology. 2006;48:505–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Goteri G, Lucarini G, Zizzi A, Costagliola A, Giantomassi F, Stramazzotti D, et al. Comparison of germinal center markers CD10, BCL6 and human germinal center-associated lymphoma (HGAL) in follicular lymphomas. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:97. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]