Abstract

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a benign papulosquamous disorder seen commonly in clinical practice. Despite its prevalence and benign nature, there are still times when this common disorder presents in an uncommon way or course posing diagnostic or management problems for the treating physician. The etiopathogenesis of PR has always been a dilemma, and extensive research is going on to elicit the exact cause. This review focuses mainly on the difficult aspects of this benign common disorder such as etiopathogenesis, atypical manifestations, recurrent cases, differential diagnosis, therapy and pregnancy considerations. Although we could not find a black and white solution to all these problems, we have tried to compile the related literature to draw out some conclusions.

Keywords: Acyclovir, human herpesvirus-6, 7, pityriasis rosea

Introduction

What was known?

Pityriasis rosea (PR) probably has an infective etiology

Drugs such as erythromycin and acyclovir have been tried although symptomatic management remains the best for most patients

Secondary syphilis and dermatophytosis form an important differential diagnoses in cases of PR.

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a papulosquamous disorder first described by Robert Willan in 1798 but under another terminology.[1] Subsequently, various names have been given to this disorder such as pityriasis circinata, roseola annulata, and herpes tonsurans maculosus.[2]

It typically starts with the development of a large erythematous scaly plaque also called the herald patch or mother patch on trunk or neck, which is followed by an eruption of multiple secondary small erythematous scaly lesions located predominantly on the trunk and following the lines of cleavage on the back (Christmas tree or inverted fir tree appearance). Collarette scaling is seen typically. The eruption is usually preceded by a prodrome of sore throat, gastrointestinal disturbance, fever, and arthralgia. However, since the prodrome may be mild and the eruption may occur sometime after the prodrome, the patient may not give a proper history unless elicited. The approximate incidence of PR is 0.5–2% and affects people of both sexes in 15–30 years age group although also seen commonly in elderly and children.[2] The disease is self-limiting and in most cases, the eruption improves in 2–8 weeks/time. Familial clustering has been reported, and the disease is more frequent in winters.

PR is a common condition easily diagnosed and managed by most dermatologists; however, there are certain difficult aspects or less common aspects which are faced in everyday practice. This review has tried to focus mainly on these aspects and also tried to compile the relevant literature to the best possible extent. Instead of going into detail about the known facts of the disease, we will just focus on these aspects under various headings.

Etiopathogenesis of Pityriasis Rosea

Numerous hypotheses have been postulated about the exact cause of PR, incriminating both infective agents such as viruses, bacteria, spirochetes, and noninfective etiologies such as atopy and autoimmunity.

There are various factors which have pointed toward an infectious etiology for this condition such as seasonal variations, presence of a prodrome, familial clustering in some cases and presence of herald patch (which may be correlated with the inoculation point of organism) followed by the secondary eruption and infrequent recurrences. However, despite repeated efforts, there is no definite evidence for a single infectious agent for this disorder. Search for this agent led to evaluation of a number of organisms in this disorder such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein–Barr virus, parvovirus B19, picornavirus, influenza and parainfluenza viruses, Legionella spp., Mycoplasma spp., and Chlamydia spp. infections; however, evidence exists that PR is not associated with them.[3]

There are few reports evaluating the role of streptococcus in PR based on premise that PR is usually preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection. Sharma et al. found raised ASLO titers in 37.7% of their patients and a positive therapeutic effect of erythromycin in the treatment of PR, thus suggesting the involvement of streptococcus in PR.[4] However, Parija and Thappa in a study of 20 cases and controls found that C-reactive protein was negative in all patients, ASLO titers were raised in only two patients, streptococcus hemolyticus could be isolated on throat swab in only two patients, and the results were not statistically significant when compared to controls, thus refuting the role of streptococcus in PR.[5]

Recently, there is an increasing evidence to suggest the role of human herpes virus (HHV) in PR. In 1997, Drago et al. first suggested the role of HHV 7 in etiology of PR by detecting HHV 7 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and plasma of patients with PR and not in controls, thus suggesting a probable causal relationship.[6] Subsequent studies however could not find any association between HHV 7 and PR.[7,8] Yasukawa et al. showed a causal link of HHV 6 and PR.[9] Watanabe et al. performed nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect HHV 6, HHV 7, and CMV DNA in 14 PR patients and found that HHV 7 DNA was present in lesional skin (93%), nonlesional skin (86%), saliva (100%), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (83%), and serum (100%) samples, whereas HHV 6 DNA was detected in lesional skin (86%), nonlesional skin (79%), saliva (80%), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (83%), and serum (88%) samples. By contrast, CMV DNA was not detected in these tissues. Control samples from 12 healthy volunteers and 10 psoriasis patients demonstrated rare positivity for either HHV 7 or HHV 6 DNA in the skin or serum. The results indicated that HHV 6 and 7 are both responsible for systemic active infection in a case of PR, and CMV has no role. Authors also postulated that since the virus was detected in saliva, patients were experiencing a reactivation rather than a primary infection since salivary glands act as a reservoir only in previously infected individuals. Furthermore, the low levels of these viruses in lesional skin led to the hypothesis that these viruses do not infect skin cells directly, and PR is actually a result of a reactive response to systemic viral replication. Authors also postulated that the previous negative studies may be because they did not use nested PCR and/or extracted DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue.[10] Another study by Drago et al. found herpes virus-like particles in PR lesional skin, thus further supporting the role of HHV 6 and 7 in the pathogenesis of PR.[11] Broccolo et al. further provided additional evidence by developing a calibrated quantitative real-time PCR and detecting cell-free HHV 6 and 7 in 16 and 39% of patients, with negative results in healthy controls and patients with other inflammatory diseases.[12] They also suggested like previous studies that the disease is a result of reactivation rather than primary infection. These studies also pointed toward the fact that HHV 7 reactivation might cause reactivation of HHV 6 however vice versa is not true. The role of HHV 8 has also been studied with both positive[13] and negative results.[14]

In light of the above studies, HHV 6 and 7 are the most likely etiologic agents for PR and further studies should be targeted toward establishing their definite role.

Atypical Variants of Pityriasis Rosea

Atypical manifestations of PR are commonly seen in dermatological practice, and it should be remembered that most of these variants are atypical in morphology and not in prognosis, and thus a high sense of clinical suspicion is needed to avoid overtreating a patient. However, it is also important not to ascribe any unusual or atypical skin eruption to atypical PR unless other dermatoses have been excluded. The incidence of atypical PR is 20%.[15] The atypicality may be in morphology, size, distribution, course, or symptoms.[2] Some authors believe that children are more predisposed to atypical variants than adults with atopy playing a facultative role.[16]

The various atypical morphologies described in literature are discussed below:

Vesicular: It presents as a generalized eruption of 2–6 mm vesicles or as a rosette of vesicles. It may be severely pruritic, is most commonly seen in children and young people, and may affect the head, palms, and soles. It needs to be differentiated from varicella and dyshidrosis[17]

Purpuric (hemorrhagic) PR presents as macular purpura on skin and sometimes over the oral mucosa[18]

Urticarial PR (PR urticata) presents with lesions similar to urticarial wheals often accompanied by intense pruritus[19]

Generalized papular PR is a rare form of the disorder that is more common in young children, pregnant women, and Afro-Caribbeans. It presents as multiple small 1–2 mm papules which may occur along with classic patches and plaques[20]

Lichenoid lesions can be observed in the course of atypical PR but is more commonly caused by drugs such as gold, captopril, barbiturates, D-penicillamine, and clonidine[21]

Erythema multiforme (EM)-like PR: They present with targetoid lesions along with the classical lesions of PR. An associated herpetic or dermatophytic infection should be ruled out in such cases. Histopathologically, EM and PR may show similar features except satellite cell necrosis which is a distinguishing feature seen only in EM where lymphocytes are seen attached to scattered necrotic keratinocytes[21]

Follicular: The secondary lesions here are typically follicular and present in groups or isolated fashion; however, associated classical lesions may also be present in the same patient.[16] Differential diagnoses such as follicular lichen planus, keratosis pilaris and atopic dermatitis with a follicular element should be excluded

Giant: Gigantic PR is rarely reported in the literature and was named after Darier. It consists of plaques and circles of very large size ranging from 5 cm to 7 cm wherein the individual lesions may reach the size of the palm of the patient[22]

Exfoliative dermatitis

Atypical herald patch: Herald patch may be absent in 20% of patients or present with secondary eruptions or may occur at unusual sites such as face, scalp, genitalia, or other sites

Sometimes, the two atypical variants may coexist in the same patient as reported by Sinha et al., where a 16-year-old girl presented with two atypical morphological variants-generalized papular and EM-like.[23]

The lesions may present in atypical site or distribution as described:

Inverse: Here, the lesions are predominantly present in acral and flexural areas involving axilla, groin, and face[24]

Acral: Polat reported a 14-year-old male patient who had a palmar herald patch with truncal lesions of PR.[25] Zawar described an infant with the acral distribution of both primary and secondary lesions where classical annular scaly lesions were located on wrists, palms, lower legs, feet, and sole with sparing of trunk and proximal parts of limbs.[26] In such patients, EM, syphilis, necrolytic acral erythema, and drug eruptions should be excluded

Unilateral: This is an extremely rare variant reported in both children and adult where the lesions were located on one side of body and patient had herald patch with classical secondary lesions[27,28]

Blaschkoid pattern: Here, the lesions follow the Blaschko's line[29]

Limb-girdle: Also known as PR of Vidal; here, the eruption is limited to shoulders or pelvic girdle, thus involving axilla and groins. Lesions are usually larger and more annular[2]

Oral mucosa: It may be involved in 16% of patients, and the lesions may be punctuate, erosive, bullous, or hemorrhagic but are usually asymptomatic in nature[2]

Localized: Here, the eruptions are localized to one part of the body. Ahmed and Charles-Holmes reported a 44-year-old woman with an acute onset of a localized eruption on her left breast whose morphology was similar to PR.[30] Zawar reported a case of a child who presented with the onset of PR in scalp, clinically mimicking pityriasis amiantacea.[31]

Atypical symptoms

Pruritus may or may not be present in a patient. PR irritate is a variant in which patient presents with extreme itching, especially on contact with sweat and thus has multiple excoriations over the body.[15]

Pityriasis rosea in dark-skinned

Dark-skinned individuals have been shown to have certain atypical features such as face may be involved frequently, papular lesions are more common, eruption tends to be more itchy, and subsequent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is frequent.[32]

In most of the atypical presentations above, there were some clinical pointers to the disease such as presence of prodrome, occurrence of a primary lesion followed by secondary lesion and in most cases, coexistent classical lesions were also present. Thus, a clinician should always look for these signs to make a diagnosis of PR in atypical cases. In most cases, histopathology is usually needed to rule out other simulating disorders.

These atypical variants may not fulfill the diagnostic criteria (discussed below) completely, but it should be understood that since most patients do not need specific treatment modalities, a good clinical acumen to rule out the differentials, and identify a case of atypical PR is more important than to put a case of atypical PR to the test of a diagnostic criterion.

Pityriasis Rosea and Vaccination

PR like eruptions has been reported after vaccinations such as Bacillus Calmette–Guerin, influenza, H1N1, diphtheria, smallpox, hepatitis B and pneumococcus.[2,33,34] Papakostas et al. postulated that vaccine-induced PR may be a result of reactivation of HHV virus secondary to immune stimulation by the vaccine or due to molecular mimicry with a viral epitope triggering a T-cell mediated response.[34]

Recurrent Pityriasis Rosea

Recurrences of PR are believed to be rare and studies have reported the second episode in 1-3% of patients.[35,36] Multiple recurrences (>2) are considered a very rare presentation of this very common condition. However, there are case reports of patients with more than two episodes, with a maximum of five episodes reported so far in the literature.[19,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] The exact etiology is not known but it is postulated that like other HHV viruses (varicella zoster virus and Epstein-Barr virus) which are associated with reactivation; reactivation of HHV6 and 7 (postulated in etiopathogenesis of PR) may be responsible for recurrent episodes.[40]

On literature review of these recurrent cases, it can be concluded that recurrences present in a varied fashion, i.e., the eruption may or may not be similar in morphology, severity, and distribution to the first episode; herald patch may be absent or present at a different site; there is no seasonal predominance, no particular age group or sex that gets affected, and the time interval between the episodes is variable.

Thus, the incidence of recurrent PR may just be an underestimation of the actual incidence as the cases may be seen by different physicians at different times or due to the benign nature of the condition, patient may not visit the physician or may not give a proper history of recurrence.

However, we suggest that following things should always be kept in mind before labeling a patient as a case of recurrent PR:

Venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) should be performed to rule out secondary syphilis

KOH should be performed to rule out dermatophytosis

Ideally, a biopsy should be taken to rule out other conditions that may mimic PR and present with recurrences such as guttate psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC), erythema annulare centrifugum, and nummular eczema. Eslick reported a patient who presented with a skin condition which was initially diagnosed as PR; however, due to the persistence and change in appearance of the lesions, the diagnosis was later altered to guttate psoriasis[42]

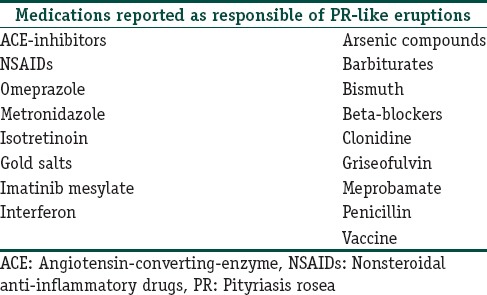

Drug-induced PR like rashes may be an important cause of recurrent PR, and thus, a proper history of drug intake must be elicited as some of the very commonly used drugs such as omeprazole and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are implicated in causing drug-induced PR. A detailed list of drugs causing PR is tabulated below [Table 1].[2,43] Clinically, drug-induced PR may not present with herald patch or typical collarette of scale and does not resolve completely until the drug is withdrawn. Histologically, these show interface dermatitis with eosinophils.

Table 1.

Drugs responsible for pityriasis rosea-like eruptions

Zawar reported a patient with recurrent PR like eruptions secondary to mustard oil application.[44] This patient was initially diagnosed as recurrent PR, but after patch testing and on proper history, it was realized that instead of atypical PR, it was just a case of contact reaction to mustard oil, thus further stressing the role of proper history of drugs or some chemical use in a case of recurrent PR.

Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Relevant Investigations in a Case of Pityriasis Rosea

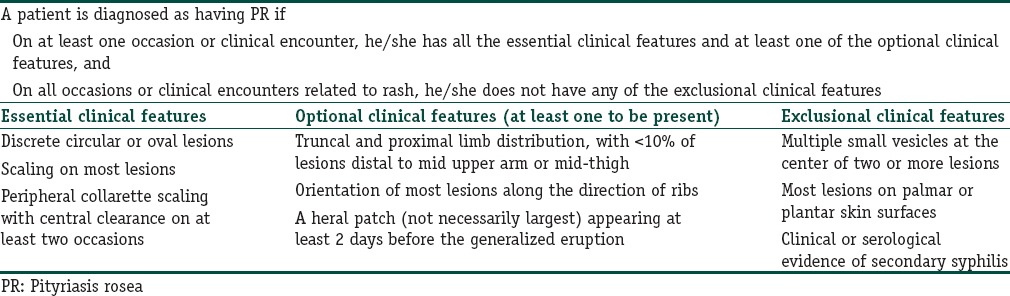

A case of PR is diagnosed mainly on clinical grounds. Chuh[45] proposed diagnostic criteria for PR [Table 2]. Zawar and Chuh studied its acceptability and validity in Indian population and found it to be 100% specific and sensitive thus establishing its validity in Indian population.[46]

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria of pityriasis rosea

However, although the criteria have been verified in Indian population, its validity in atypical cases still needs to be established as most of the atypical presentations described in literature may not strictly comply with the diagnostic criteria given by Zawar et al.

Histopathology

A biopsy is needed in atypical cases, and it mainly helps in excluding other differentials rather than diagnosing PR as the histopathological examination in a case of PR is relatively nonspecific and resembles a subacute or chronic dermatitis. Epidermal changes include focal parakeratosis, diminished granular layer, and spongiosis. Small spongiotic vesicles, although infrequently seen, are a characteristic feature. Papillary dermis shows edema with mild perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Exocytosis of infiltrate into epidermis may be seen. Studies have revealed that dyskeratotic cells in the epidermis and extravasated erythrocytes in the dermis are characteristic histopathological findings in a case of PR and are seen in approximately 60% of patients.[2,21,47,48] Herald patch shows less spongiosis, more hyperplasia, and both superficial and deep perivascular infiltration.

There are numerous conditions which need to be excluded while diagnosing a case of PR and have been discussed below:

Secondary syphilis: This is important, especially in sexually active adults. A detailed sexual history followed by examination to look for signs of healed chancre, lymphadenopathy, mucosal lesions, and lesions on palms and soles should be done. Patient should be subjected to a VDRL testing or any of the specific or nonspecific treponemal tests available for confirmation. Histopathology will show the presence of plasma cells in a case of secondary syphilis

Dermatophytosis: The herald patch may mimic tinea corporis, and thus, a KOH examination should be performed

Guttate psoriasis: It presents as scaly erythematous plaques and can be differentiated by the lack of herald patch, typical rain drop appearance of lesions rather than Christmas tree appearance, the presence of Auspitz sign and finally a biopsy

Pityriasis lichenoides chronica: The secondary lesions of PR might be confused with PLC, however, in a case of PLC, the herald patch is absent, and course of diseases is prolonged and may last from months to years. Thus, it is an important differential in a case of PR which does not resolute

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE): It can be differentiated by history of photosensitivity, other signs of LE, photodistribution of lesions, and histopathology, which in case of SCLE will show epidermal atrophy and basal vacuolar change

Nummular eczema: The lesions do not show a predominance for trunk, are itchy, may show oozing, and respond rapidly to topical steroids

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: Initial patch stage shows predominance for trunk, is mildly pruritic, and does not respond to topical steroids, thus closely mimicking PR. Multiple serial biopsies are needed for final diagnosis.

Other rare differentials that might need to be excluded are lichen planus, erythema annulare centrifugum, pityriasis versicolor, pigmentary purpuric dermatoses (in case of purpuric PR), drug eruptions, vasculitis, and pityriasis versicolor.

Treatment of Pityriasis Rosea

As PR is a self-limiting disorder, most patients just need to be counseled regarding the natural course of the disease instead of putting them on an aggressive treatment protocol. Most patients would just need emollients, antihistaminics, and sometimes topical steroids to control pruritus. There are a lot of concerns with therapeutics in this disorder:

Since the disease is self-limiting, it is always difficult to determine if the disease improved with medications or followed its natural course

Since the etiopathogenesis is not clearly known, therapeutics aimed to a particular etiologic agent cannot be relied upon

Most of the treatments tried are based on few reports and thus anecdotal in nature

There are conflicting results for almost all the therapies that have been tried

Benefit-risk ratio will always be biased toward risk in a disease which follows a natural course of resolution and thus, the concern of adverse effect with any treatment used

Use of antibiotics may increase the chances of resistance in the individual and society as a whole

It is usually not clear whether the treatment being used is directed to control the symptoms or alter the natural course of disease or to hasten resolution of skin lesions or to improve the quality of life, because in this disease, the symptomatology and the extent of rash are not directly correlated.

Numerous therapies have been tried in various studies [Table 3], but the Cochrane review did not find adequate evidence for the efficacy of any of these.[49] Cochrane review on interventions in PR excluded 13 out of 16 studies due to lack of proper randomization. Thus, it was suggested that better-randomized studies should be performed, and since there is no well-proven intervention, all studies evaluating any particular modality should be placebo controlled. Furthermore, the outcome measures with any treatment should not be evaluated beyond 2 weeks as spontaneous remission is likely at 2–12 weeks.

Table 3.

Treatments tried for pityriasis rosea

There are no significant studies regarding the use of antihistamines and emollients on an extensive literature search. The rest of the therapies used have been discussed in detail below.

Steroids

Though topical and systemic steroids are sometimes used in cases of PR, there is a lack of substantial evidence supporting or refuting their use. There is not much of published literature on the use of corticosteroids (CS) in PR. Leonforte published an article reporting exacerbation of PR on CS administration. They included 18 patients, in which 13 patients were already treated with CS and 5 were given steroids to assess its efficacy. Most of the patients experienced a mild or severe exacerbation in the form of increased pruritus, irritation, or number of lesions, and it was more common and severe in patients in whom CS was started in the initial stage of the disease.[50] Hence, considering the viral etiology of the disease, oral steroids may not be a good option, and use of topical preparations should be limited to patients experiencing severe pruritus. However, further studies are needed to establish the role of CS in PR.

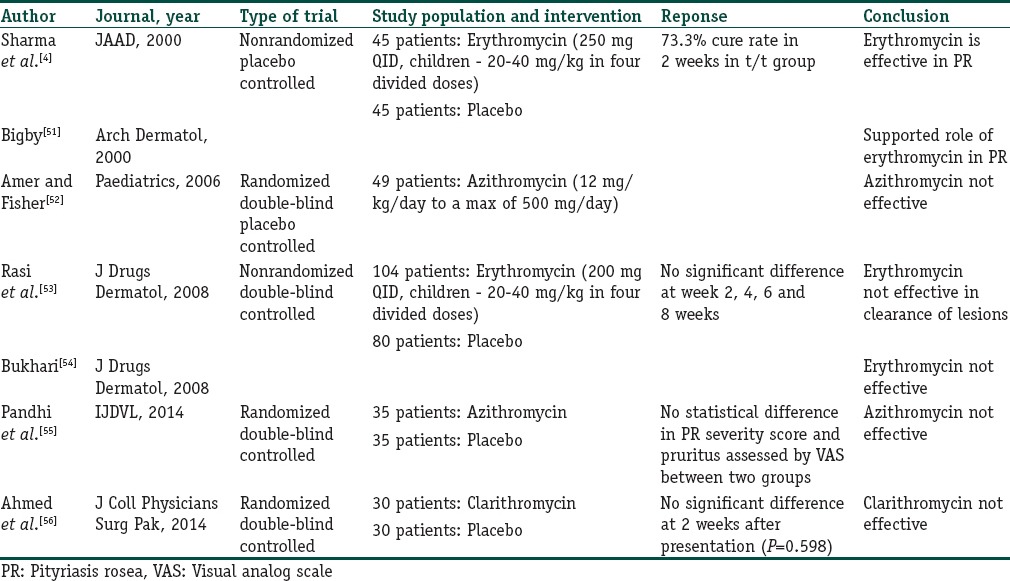

Macrolides

The mechanism of action of macrolides in PR is not known; however, it is believed that they act more through their anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions rather than the antibiotic effect. The various studies evaluating the role of macrolides in PR have been tabulated below [Table 4].

Table 4.

Studies evaluating the role of macrolides in pityriasis rosea

As can be concluded from Table 4, although the initial study showed a favorable response to erythromycin, subsequent studies found macrolides to be ineffective and comparable to placebo treatment. Thus, there is no rationale of using these antibiotics until further large-scale randomized controlled studies are done since the risk of developing resistance to these antibiotics may outweigh the probable benefit they may offer.

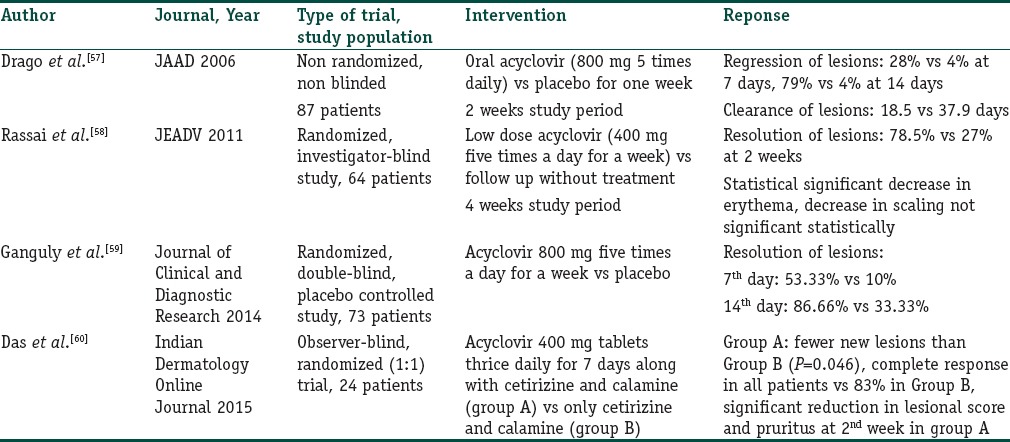

Antivirals

The rationale behind the use of antivirals in PR is that the course of the disease follows that of a viral exanthem, i.e., seasonal occurrence, presence of prodromal symptoms, self-resolution, and also probable involvement of HHV 6 and 7 in its etiopathogenesis. Acyclovir is the only antiviral that has been tried and various studies assessing its efficacy have been tabulated [Table 5]. However, a note should be made of the fact that although acyclovir has been shown to be effective against HHV 6, it is not very effective against HHV 7 as this virus lacks thymidine kinase gene, on which the action of acyclovir is dependent. Thus, other antivirals such as foscarnet, cidofovir and ganciclovir which have activity against HHV might be effective in PR, however, in view of serious side effects such as myelosuppression and nephrotoxicity associated with them, there is no rationale of their use in a benign disorder like PR and thus they have not been tried as yet.

Table 5.

Studies evaluating the role of acyclovir in PR

As can be deciphered from Table 5, acyclovir does lead to a faster resolution of lesions as compared to placebo, and thus may be an effective treatment modality. Furthermore, it is important to note that the response is significantly better even at the 7th day when spontaneous resolution is unlikely, thus pointing toward the therapeutic effectiveness of acyclovir. Drago et al. postulated that earlier the treatment is started, better is the response with better clearance (17.2 days vs. 19.7 days) and fewer new lesions in patients treated in the 1st week than in those treated later.[57] Ganguly however found no significant difference in clearance if the treatment was started earlier.[59] Since most of the herpes virus infections need an early institution of antiviral agents; in light of above findings, we believe that this aspect needs to be studied in further detail with respect to PR, and till then, institution of acyclovir therapy should not be withheld even if patients present later than 1 week. This is also because cases which prompt an aggressive treatment from the caregiver are those which do not improve on symptomatic treatment and thus present more than a week after the onset. Regarding dose of acyclovir, both high and low doses have been seen to be beneficial; thus, a comparative study needs to be done to know if one is better than other. Despite the probable therapeutic effectiveness, there is a single report of PR occurring in a patient on suppressive acyclovir therapy for herpes genitalis.[61]

Comparison Between Acyclovir and Erythromycin

There are two studies which have compared the above two modalities, i.e., high dose acyclovir and erythromycin and both have found acyclovir to be more effective than erythromycin. In the study by Ehsani et al., 30 patients were recruited and at the end of 8 weeks, 13 versus 6 patients achieved complete cure in acyclovir and erythromycin group, respectively with a P < 0.05. Resolution of pruritus was also faster with acyclovir although the results were not significant statistically.[62] In another study by Amatya et al., 42 patients were enrolled, and results with acyclovir were again found to be better at 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks.[63]

Thus, acyclovir seems to be a promising therapy for treatment of PR leading to faster resolution of lesions and also helping in relieving pruritus.

Phototherapy

There are few studies evaluating the role of phototherapy in PR. This might work by altering the immunology in the skin and has been used on the premise of its usefulness in various other inflammatory disorders. Merchant and Hammond did first controlled study in 1974 using quartz lamp in 66 patients and found better results on treated site.[64] Subsequently, Arndt et al. did a controlled study on 20 patients using ultraviolet B (UVB) therapy (0.8 Minimal erythema dose (MED) dose on day 1 with 17% increase daily for 5 days) on the right side with shielding of the left side. The extent of disease and pruritus control was better on treated side (50% and 47% respectively).[65] Leenutaphong and Jiamton did a bilateral comparison study by giving UVB (80% of MED followed by 10–20% increase if no erythema in 10 daily doses) on the right side and 1 J of UVA radiation on the left side as placebo. Ten daily erythemogenic doses of UVB exposure significantly decreased the disease severity score with significant difference seen after the third sitting. However, in the follow-up period at 2 and 4 weeks, there was no difference in severity score or pruritus; thus, the authors concluded that UVB decreased the severity scores during treatment but did not alter the course of disease or pruritus.[66] Castanedo-Cazares et al.[67] reported worsening of a patient after phototherapy with UVB thus raising doubts of its therapeutic effectiveness in PR. Recently, Lim et al.[68] have used low dose UVA1 phototherapy (starting with 10–20 J/cm2 and increasing to 30 J/cm2 given 2–3 times a week till improvement) to treat PR with significant improvement in severity score after 2–3 treatments. There was also improvement in pruritus. Based on the results of above studies, phototherapy has a conflicting role in PR and thus, further studies are needed to fully establish its role.

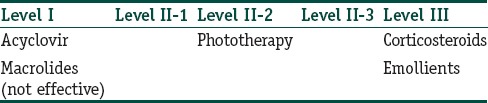

The following table enlists the level of evidence for various interventions tried in PR [Table 6].

Table 6.

Level of evidence for treatment options in pityriasis rosea

Pregnancy and Pityriasis Rosea

This topic needs special mention as lately, there are conflicting reports about adverse pregnancy outcomes in females developing PR during pregnancy, and most of the clinicians are unaware about this fact. The incidence of PR in pregnancy has been reported to be 18% versus 6% in general population.[69] Drago et al. studied 38 women who developed PR during pregnancy out of which 9 had premature delivery and 5 miscarried. They found the rate of abortion was 62% in women who developed PR within 15 weeks of gestation. Six cases showed neonatal hypotonia, weak motility, and hyporeactivity; however, all neonates eventually followed normal growth trends. All patients showed high immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody titers for HHV 6 and 7 and negative IgM antibodies. Embryonic tissue obtained from one female showed signs of viral cytopathic damage pointing toward the fact that PR is actually a systemic HHV infection leading to intraplacental transmission of virus. Thus, authors postulated that PR occurring in pregnancy, especially in the first trimester, may be a marker of possible adverse pregnancy outcome.[70] Authors further extended their study to include 61 pregnant patients with PR and found similar results.[71] However, this has been refuted by other authors.[72] Chuh et al. reported two pregnant patients with PR whose pregnancies and delivery were uneventful and bore healthy normal children.[73] Thus, further studies are needed to establish the causal relation between PR and adverse pregnancy outcome and till then, all pregnant females developing PR should be kept under strict follow-up. All pregnant females with PR, however, should undergo serological screening for syphilis. They should be managed with emollients and antihistaminics, and systemic therapy should be avoided.

Conclusion

Although lot is known about PR, there are still a lot of gray areas which need to be addressed in future studies. Through this article, we have tried to bring together the literature published for the same. We conclude that viral etiology is probably the most likely cause of PR, and thus, antivirals should be given in early stages of PR itself. All recurrent cases should be worked up properly, and all pregnant females developing PR should be kept under close follow-up.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Human herpes virus is the most likely etiological agent causing PR

Although the diagnostic criteria are available and verified in Indian population, its validity in atypical cases still needs to be established

Erythromycin is ineffective in PR whereas acyclovir is a promising therapy

A careful history of drugs or chemical exposure should be taken in all cases of recurrent PR

All pregnant females developing PR should be kept under strict follow-up.

References

- 1.Weiss L. Pityriasis rosea – An erythematous eruption of internal origin. JAMA. 1903;41:20–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zawar V, Jerajani H, Pol R. Current trends in pityriasis rosea. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2010;5:325–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuh A, Chan H, Zawar V. Pityriasis rosea – Evidence for and against an infectious aetiology. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132:381–90. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804002304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma PK, Yadav TP, Gautam RK, Taneja N, Satyanarayana L. Erythromycin in pityriasis rosea: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 Pt 1):241–4. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parija M, Thappa DM. Study of role of streptococcal throat infection in pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:171–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.44787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drago F, Ranieri E, Malaguti F, Battifoglio ML, Losi E, Rebora A. Human herpesvirus 7 in patients with pityriasis rosea. Electron microscopy investigations and polymerase chain reaction in mononuclear cells, plasma and skin. Dermatology. 1997;195:374–8. doi: 10.1159/000245991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kempf W, Adams V, Kleinhans M, Burg G, Panizzon RG, Campadelli-Fiume G, et al. Pityriasis rosea is not associated with human herpesvirus 7. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1070–2. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.9.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe T, Sugaya M, Nakamura K, Tamaki K. Human herpesvirus 7 and pityriasis rosea. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:288–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasukawa M, Sada E, MacHino H, Fujita S. Reactivation of human herpesvirus 6 in pityriasis rosea. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:169–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe T, Kawamura T, Jacob SE, Aquilino EA, Orenstein JM, Black JB, et al. Pityriasis rosea is associated with systemic active infection with both human herpesvirus-7 and human herpesvirus-6. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:793–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drago F, Malaguti F, Ranieri E, Losi E, Rebora A. Human herpes virus-like particles in pityriasis rosea lesions: An electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:359–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broccolo F, Drago F, Careddu AM, Foglieni C, Turbino L, Cocuzza CE, et al. Additional evidence that pityriasis rosea is associated with reactivation of human herpesvirus-6 and -7. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1234–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prantsidis A, Rigopoulos D, Papatheodorou G, Menounos P, Gregoriou S, Alexiou-Mousatou I, et al. Detection of human herpesvirus 8 in the skin of patients with pityriasis rosea. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:604–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuh AA, Chan PK, Lee A. The detection of human herpesvirus-8 DNA in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in adult patients with pityriasis rosea by polymerase chain reaction. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:667–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.González LM, Allen R, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA. Pityriasis rosea: An important papulosquamous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:757–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zawar V, Chuh A. Follicular pityriasis rosea. A case report and a new classification of clinical variants of the disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:36–9. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2012.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia RL. Letter: Vesicular pityriasis rosea. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierson JC, Dijkstra JW, Elston DM. Purpuric pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:1021. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80661-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuh A, Zawar V, Lee A. Atypical presentations of pityriasis rosea: Case presentations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:120–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardin RM, Ritter SE, Murchland MR. Papular pityriasis rosea. Cutis. 2002;70:51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Relhan V, Sinha S, Garg VK, Khurana N. Pityriasis rosea with erythema multiforme – Like lesions: An observational analysis. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:242. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.110855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klauder JV. Pityriasis rosea with particular reference to its unusual manifestations. JAMA. 1924;82:178–83. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg VK. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: A case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibney MD, Leonardi CL. Acute papulosquamous eruption of the extremities demonstrating an isomorphic response. Inverse pityriasis rosea (PR) Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:651–654. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polat M, Yildirim Y, Makara A. Palmar herald patch in pityriasis rosea. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:e64–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2011.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zawar V. Acral pityriasis rosea in an infant with palmoplantar lesions: A novel manifestation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2010;1:21–3. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.73253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brar BK, Pall A, Gupta RR. Pityriasis rosea unilateralis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:42–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zawar V. Unilateral pityriasis rosea in a child. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:54–6. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2010.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ang CC, Tay YK. Blaschkoid pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:906–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed I, Charles-Holmes R. Localized pityriasis rosea. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:624–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zawar V. Pityriasis amiantacea-like eruptions in scalp: A novel manifestation of pityriasis rosea in a child. Int J Trichology. 2010;2:113–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.77524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amer A, Fischer H, Li X. The natural history of pityriasis rosea in black American children: How correct is the “classic” description? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:503–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh CW, Yoon J, Kim CY. Pityriasis rosea-like rash secondary to intravesical Bacillus calmette-guerin immunotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:360–2. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papakostas D, Stavropoulos PG, Papafragkaki D, Grigoraki E, Avgerinou G, Antoniou C. An atypical case of pityriasis rosea gigantea after influenza vaccination. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:119–23. doi: 10.1159/000362640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjornberg A, Hellgren L. Pityriasis rosea. A statistical, clinical, and laboratory investigation of 826 patients and matched healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1962;42(Suppl 50):1–68. doi: 10.2340/0001555542168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chuang TY, Ilstrup DM, Perry HO, Kurland LT. Pityriasis rosea in Rochester, Minnesota, 1969 to 1978. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:80–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halkier-Sørensen L. Recurrent pityriasis rosea. New episodes every year for five years. A case report. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70:179–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Recurrent pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1998;64:237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zawar V, Kumar R. Multiple recurrences of pityriasis rosea of Vidal: A novel presentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e114–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drago F, Broccolo F, Rebora A. Pityriasis rosea: An update with a critical appraisal of its possible herpesviral etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:303–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sankararaman S, Velayuthan S. Multiple recurrences in pityriasis rosea – A case report with review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:316. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.131457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eslick GD. A typical pityriasis rosea or psoriasis guttata?. Early examination is the key to a correct diagnosis. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:788–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atzori L, Pinna AL, Ferreli C, Aste N. Pityriasis rosea-like adverse reaction: Review of the literature and experience of an Italian drug-surveillance center. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zawar V. Pityriasis rosea-like eruptions due to mustard oil application. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:282–4. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.16625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chuh AA. Diagnostic criteria for pityriasis rosea: A prospective case control study for assessment of validity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:101–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00519_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zawar V, Chuh A. Applicability of proposed diagnostic criteria of pityriasis rosea: Results of a prospective case-control study in India. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:439–42. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.119950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ackerman AG. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1978. Histological Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Diseases; pp. 233–5. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okamoto H, Imamura S, Aoshima T, Komura J, Ofuji S. Dyskeratotic degeneration of epidermal cells in pityriasis rosea: Light and electron microscopic studies. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:189–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chuh AA, Dofitas BL, Comisel GG, Reveiz L, Sharma V, Garner SE, et al. Interventions for pityriasis rosea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD005068. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005068.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leonforte JF. Pityriasis rosea: Exacerbation with corticosteroid treatment. Dermatologica. 1981;163:480–1. doi: 10.1159/000250220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bigby M. A remarkable result of a double-masked, placebo-controlled trial of erythromycin in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:775–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amer A, Fischer H. Azithromycin does not cure pityriasis rosea. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1702–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rasi A, Tajziehchi L, Savabi-Nasab S. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bukhari IA. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pandhi D, Singal A, Verma P, Sharma R. The efficacy of azithromycin in pityriasis rosea: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:36–40. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.125484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahmed N, Iftikhar N, Bashir U, Rizvi SD, Sheikh ZI, Manzur A. Efficacy of clarithromycin in pityriasis rosea. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2014;24:802–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drago F, Vecchio F, Rebora A. Use of high-dose acyclovir in pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:82–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rassai S, Feily A, Sina N, Abtahian S. Low dose of acyclovir may be an effective treatment against pityriasis rosea: A random investigator-blind clinical trial on 64 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:24–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ganguly S. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy of oral acyclovir in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:YC01–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8140.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Das A, Sil A, Das NK, Roy K, Das AK, Bandopadhyay D. Acyclovir in pityriasis rosea: An observer blind, randomized controlled trial of effectiveness, safety and tolerability. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:181–4. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.156389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mavarkar L. Pityriasis rosea occurring during acyclovir therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:200–1. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.32752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ehsani A, Esmaily N, Noormohammadpour P, Toosi S, Hosseinpour A, Hosseini M, et al. The comparison between the efficacy of high dose acyclovir and erythromycin on the period and signs of pitiriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:246–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.70672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Amatya A, Rajouria EA, Karn DK. Comparative study of effectiveness of oral acyclovir with oral erythromycin in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2012;10:57–61. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v10i1.6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Merchant M, Hammond R. Controlled study of ultraviolet light for pityriasis rosea. Cutis. 1974;14:548–9. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arndt KA, Paul BS, Stern RS, Parrish JA. Treatment of pityriasis rosea with UV radiation. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:381–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leenutaphong V, Jiamton S. UVB phototherapy for pityriasis rosea: A bilateral comparison study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:996–9. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Castanedo-Cazares JP, Lepe V, Moncada B. Should we still use phototherapy for pityriasis rosea? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:160–1. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lim SH, Kim SM, Oh BH, Ko JH, Lee YW, Choe YB, et al. Low-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy for treating pityriasis rosea. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:230–6. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Corson EF, Luscombe HA. Coincidence of pityriasis rosea with pregnancy. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:562–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530170088012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drago F, Broccolo F, Zaccaria E, Malnati M, Cocuzza C, Lusso P, et al. Pregnancy outcome in patients with pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5 Suppl 1):S78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Drago F, Broccolo F, Javor S, Drago F, Rebora A, Parodi A. Evidence of human herpesvirus-6 and -7 reactivation in miscarrying women with pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:198–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bianca S, Ingegnosi C, Ciancio B, Gullotta G, Randazzo L, Ettore G. Pityriasis rosea in pregnancy. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24:277–8. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chuh AA, Lee A, Chan PK. Pityriasis rosea in pregnancy – Specific diagnostic implications and management considerations. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;45:252–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]