Abstract

Acne vulgaris is usually considered as a skin disorder that primarily affects adolescents reaching a peak at the age of 14–17 years in females and 16–19 years in males. However, recent epidemiologic studies have shown that a significant number of female patients aged >25 years experience acne. As it is regarded as a disease of teenagers, adults are more apprehensive and experience social anxiety. Hence, adult onset acne has become a matter of concern.

Keywords: Adult acne, hirsutism, hormonal acne, oral contraceptive pills

Introduction

What was known?

Prime etiology in causing adult onset acne is known to be a hormonal imbalance. Hormonal therapy is considered as the main treatment modality.

Incidence of adult onset acne (AOA) is increasing, and women comprise the majority of cases.[1,2] AOA is defined as chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous units occurring beyond the age of 25 years.[3] It commonly affects females (14%) between the age of 25 and 50 years.[4]

Clinical Presentation

Two distinct types:

Persistent acne: Continuation of acne from adolescence to adult life or middle age. It is characterized by deep-seated painful inflammatory lesions, mainly papules, and nodules commonly involving jaw line, lower third of face and neck[5]

-

Late-onset acne (chin and sporadic acne are recalcitrant in nature):[1] Acne occurring for the first time after the age of 25 years.

- Chin acne

- Sporadic acne: Etiology may embrace systemic illness or it may be idiopathic.[5]

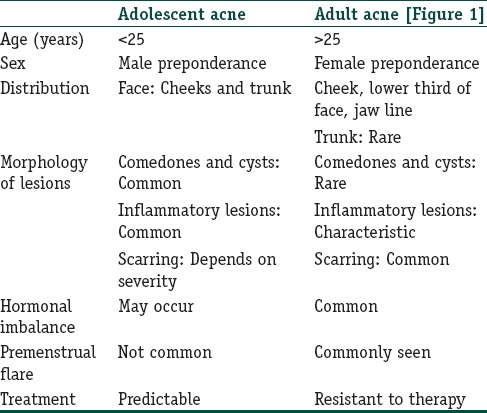

Clinical differences between adolescent acne and adult onset acne are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical difference between adolescent and adult onset acne

Etiology

Genetic

Genetic influence has been established by very high concordance between monozygotic twins. Goulden et al. reported that 50% patients had a first degree relative with AOA, which confirms familial predisposition.[6]

Stress

It is implicated in acne by action on adrenal-pituitary axis leading to increased androgen production, seborrhea, and comedogenesis.[1]

Smoking

Cigarette smoke contains high amounts of arachidonic acid and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which stimulate a phospholipase A2-dependent inflammatory pathway.[7]

Microbial flora

Adult acne have increased tendency of antibacterial resistant Propionibacterium acnes.[1]

Cosmetic products

Ingredients such as lanolin, petrolatum, and vegetable oils have been found to be comedogenic.[1]

Hormones

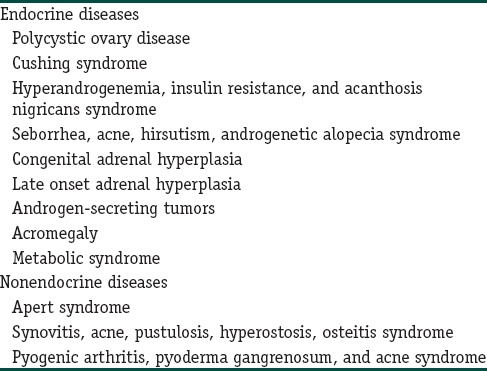

Androgens can be synthesized locally in sebaceous glands from adrenal precursor hormone dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate. Mean serum androgen levels were found to be in higher normal range. This observation suggested that androgens act directly on sebaceous gland, or it may be more sensitive to the effect of androgens.[1] Hyperandrogenism has also been reported in studies by various studies.[3] Higher levels of 5α reductase (enzyme that converts testosterone to more androgenic dihydrotestosterone), 3α-androstanediol glucuronide, and androsterone glucuronide (tissue derived androgens) have been also found to be raised. It is unclear as to whether acne is mediated by serum androgens, locally produced androgens, or a combination of both. Studies have shown the association of polycystic ovarian disease (PCOD) with AOA in 52–82% of patients, reduced activity of 21α hydroxylase (late onset adrenal hyperplasia) in 11.8% patients; adrenal androgens were mildly raised implying end organ hypersensitivity as a central factor in pathogenesis of AOA.[8] List of systemic diseases associated with AOA has been summarized in Table 2.[9]

Table 2.

Systemic diseases associated with adult onset acne

Insulin-like growth factor-1

Insulin-like growth factor-1 stimulates adrenal androgen production and also inhibits hepatic sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance contribute to high prevalence of acne in women with PCOD.[4]

Follicular pore diameter increases with age

Allam[10] observed that patients with late-onset acne have larger pores than individuals of the same age who do not have acne.

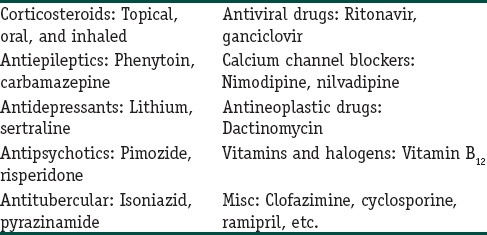

Drugs

Drugs are listed in Table 3.[1]

Table 3.

Drugs implicated in causing adult onset acne

Management

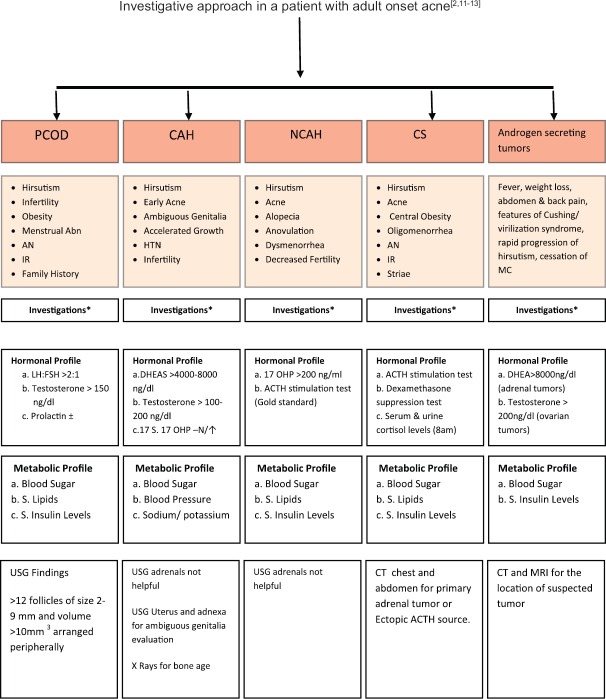

The history should be followed by clinical examination and then relevant investigations [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Investigative approach in a patient with adult onset acne. Abn: Abnormality, AN: Acanthosis nigricans, IR: Insulin resistance, HTN: Hypertension, MC: Menstrual cycle, DHEAS: Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, 17OHP: 17 hydroxyprogesterone, ACTH: Adrenocorticotropic hormone, PCOD: Polycystic ovarian disease, CAH: Congenital adrenal hyperplasia, NCAH: Nonclassical CAH, CS: Cushing syndrome, N/↑: Normal or increased, CT: Computed tomography, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

Figure 1.

Inflammatory acne and excessive hair growth over cheeks and chin in a 30-year-old female patient

Important history points include the following:[1,8,11,12]

Age of onset (sudden or late onset) – favors PCOD

Family history

Medical history of associated comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or recent systemic illness

History of any drug intake

Obstetric/gynecological history including menstrual history (age of menarche, regular cycles), infertility, oral contraceptive pills (OCP), and hormonal intrauterine devices (progestogen) and pregnancy

-

History of any precipitating cause:

- Sun exposure

- Seasonal variation

- Use of cosmetics and pomades

- Stress

- Premenstrual flare.

Clinical assessment incorporates:[1,8,11,12]

Type of lesions

Distribution of lesion

Severity and grading of acne

-

Features of cutaneous hyperandrogenism (CH):

- Hirsutism (modified Ferriman and Gallwey method)

- Androgenetic alopecia

- Seborrhea

- Acanthosis nigricans.

-

Signs of virilization:

- Clitoromegaly

- Deepening of voice

- Reduced muscle mass

- Decreased breast size.

Features of Cushing syndrome enumerated in Figure 2.

Appropriate investigations are mentioned in Figure 2.[2,11,12,13] Hormone profile should ideally be performed on day 1–3 of menstrual cycle. Fasting sample should be preferred if the patient has amenorrhea. As hormones exhibit diurnal variation, these should be measured in the early morning. Oral contraceptive pills should be discontinued 4–6 weeks before hormone evaluation.[11]

Treatment

The general principles of treatment of adult acne are essentially the same as acne in younger age group except for some minor differences that should be considered.[1]

Topical therapy

Topical retinoids should be considered as a first-line therapy for mild to moderate inflammatory acne as well as comedonal acne. When used in combination with topical or oral antimicrobial agent, apparently attain more rapid efficacy. However, since retinoids can irritate the older skin, shorter duration of application should be recommended.[1]

Systemic therapies

Systemic antibiotics

The preferred agents are second-generation tetracyclines (oxytetracycline, minocycline, and lymecycline) and erythromycin group of drugs.[1] These may show a slow response in AOA, and even treatment failure has been reported in 82% of adult women.[6] Patient should be warned regarding drug interactions if she is on concomitant oral contraceptives (OCs) and oral antibiotics should be stopped as soon as inflammatory lesions subside.

Oral retinoids

Seukeran and Cunliffe used low-dose systemic isotretinoin (0.25 mg/kg/day) for a period of 6 months which helped in resolution and remission of acne.[14]

Hormonal therapy

Hormonal therapy may even be beneficial in patients with normal serum androgen levels.[11] Excellent candidates for hormonal therapy are:[12]

AOA

Recalcitrant acne

PCOD, presence of anovulation (<9 cycles per year or cycles >40 days apart)

SAHA syndrome: Seborrhea, acne, hirsutism, and androgenetic alopecia

HAIR-AN syndrome: Hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans

CH.

Hormone agents comprise two groups.[12]

-

Drugs acting by decreasing androgen synthesis from adrenals and ovaries

- OCs and glucocorticoids

-

Drugs acting by blocking androgen receptors

- Cyproterone acetate (CPA), spironolactone, drospirenone, and flutamide.

Cyproterone acetate

It acts by blocking androgen receptors. It is often used in combination with estrogens in the OCP, with ethinyl estradiol (EE) 35 ug. When used as monotherapy, it is given from day 1 to 10 of the menstrual cycle.[11] Common side effects include menstrual abnormalities, breast tenderness, nausea, vomiting, fluid retention, leg edema, headache, and liver dysfunction.[15]

Spironolactone

It is an aldosterone and 5α receptor antagonist. It decreases androgen levels by increasing SHBG. It is given in a dose of 50–100 mg after food, but response can be seen with a lower dose of 25 mg once or twice daily.[11] It is cost effective and well tolerated.[12] Side effects include irregular menstrual cycles, breast tenderness, hypotension, and hyperkalemia.

Flutamide

It is a nonsteroidal androgen receptor blocker and is used in a dose of 250 mg twice daily. Liver functions should be monitored.[15] Bicalutamide, a new derivative, is less hepatotoxic than flutamide.[12]

Oral contraceptives

Mechanism of action:

Decrease ovarian androgen production

Increase SHBG production

Inhibit 5α reductase activity.

Common combinations used:

CPA 2 mg + EE 0.035 mg

Drospirenone 3 mg + EE 0.03 mg

Desogestrel 0.15 mg + EE 0.03 mg

Desogestrel 0.15 mg + EE 0.02 mg.

Started on day 1 of menstrual cycle (if contraception is required) or day 5 (if date of menstruation is to be maintained).[11,12,15]

Side effects

Weight gain, breast tenderness, breakthrough bleeding, stroke, myocardial infarction, melasma and mood changes.

Corticosteroids

These are reserved for the patients with congenital or nonclassical adrenal hyperplasia.[11]

Insulin-sensitizing agents

Metformin and thiazolidinediones (rosiglitazone/pioglitazone)

These agents act by improving insulin sensitivity, and subsequently, decrease circulating androgen levels. In addition, these agents have a role in the treatment of PCOD. Metformin is given in a dose of 500 mg- 2000mg/day. Its side effects are diarrhea, nausea, taste changes, and lactic acidosis.[11] Upcoming drugs with controversial role: Ketoconazole, lymecycline, oral zinc, and cimetidine: these newer drugs seem to have antiandrogenic role.[11,12]

For cyproterone acetate and flutamide, periodic monitoring of liver function tests is required. Spironolactone has a tendency to cause hyperkalemia and ECG changes. So S. potassium and ECG should be checked. For newer generation OCs, no specific monitoring is warrented unless patient is in high risk group. Glucocorticoids warrants monitoring of blood pressure, blood sugar and electrolytes.[11,12]

Blue light therapy

It has a significant role in reducing mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne. Porphyrin (coproporphyrin III) produced within P. acnes releases free radicals on irradiation by 420 nm and shorter wavelengths of light; these free radicals effectively kill the bacteria.[16]

Treatment of acne in pregnant, lactating women, or those who wish to conceive

Topical medication is the first-line treatment for acne vulgaris in this group. These include antibiotics (erythromycin and clindamycin), azelaic acid, and salicylic acid. Second-line treatment consists of oral macrolides (erythromycin azithromycin). Blue-violet or red light phototherapy may be used in addition to topical and/or oral therapies. Hormonal therapy, antibiotics consisting of tetracyclines, and both oral and topical retinoids should be avoided.[17]

Conclusion

AOA is generally considered refractory to the treatment. A proper history and clinical assessment aids in reaching to a correct diagnosis and hence management accordingly.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Adult onset acne is a multifactorial disease. Thus, investigative and therapeutic approach is needed to avoid resistance to therapy. Low-dose isotretinoin and new emerging modalities such as blue light therapy are proven to have a beneficial role.

References

- 1.Williams C, Layton AM. Persistent acne in women: Implications for the patient and for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:281–90. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: Practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seirafi H, Farnaghi F, Vasheghani-Farahani A, Alirezaie NS, Esfahanian F, Firooz A, et al. Assessment of androgens in women with adult-onset acne. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1188–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balta I, Ekiz O, Ozuguz P, Ustun I, Karaca S, Dogruk Kacar S, et al. Insulin resistance in patients with post-adolescent acne. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:662–6. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks R. Acne and its management beyond the age of 35 years. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:459–62. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200405060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goulden V, Clark SM, Cunliffe WJ. Post-adolescent acne: A review of clinical features. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Layton AM. Disorders of the sebaceous glands. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. USA: Wiley Blackwell; 2010. p. 4234. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khunger N, Kumar C. A clinico-epidemiological study of adult acne: Is it different from adolescent acne? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:335–41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.95450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uzuncakmak TK, Karadag AS, Akdeniz N. Acne and systemic diseases. EMJ Dermatol. 2015;3:73–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allam SG. Cardiff: University of Wales; 1991. Acne Vulgaris in the Sixth Decade and Beyond [MSc Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakshmi C. Hormone therapy in acne. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:322–37. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.110765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubba R, Bajaj AK, Thappa DM, Sharma R, Vedamurthy M, Dhar S, et al. Acne in India: Guidelines for management – IAA consensus document. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75(Suppl 1):1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witchel SF. Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012;19:151–8. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283534db2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seukeran DC, Cunliffe WJ. Acne vulgaris in the elderly: The response to low-dose isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:99–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebede TL, Arch EL, Berson D. Hormonal treatment of acne in women. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold MH, Andriessen A, Biron J, Andriessen H. Clinical efficacy of self-applied blue light therapy for mild-to-moderate facial acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:44–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73:779–87. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]