Abstract

A 32-year-old male presented to Dermatology outpatient Department with complaints of a single nonhealing ulcer on his right thigh. This lesion was there for the last 1 months. It had begun as a small nodule and increased up to the present size of 3 cm with an oozing and ulcerated surface and thickened everted margins. The systemic investigations were normal which included hemogram, biochemistry, including liver and renal function tests, chest X-ray, ultrasonography of abdomen, computed tomography of the thorax, and abdomen. Skin biopsy revealed multiple rounds to oval spores with surrounding halo intracellularly as well as extracellularly. A diagnosis of deep fungal infection as histoplasmosis was made and confirmed on culture.

Keywords: Fungus, histoplasmosis, immunocompetent

Introduction

What was known?

Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis is rare in an immunocompetent individual more so from a non-endemic region. The skin lesions mostly are papulo-nodular.

Histoplasmosis is a systemic mycosis. It is a deep fungal infection endemic in West Bengal and some areas of Southern India.[1] It can present as a mucocutaneous lesion, pulmonary and as a generalized systemic infection. Histoplasmosis is frequently encountered in immunocompromised or patients on immunosuppressants. We report a case who presented to us with a nonhealing ulcer and was subsequently diagnosed as histoplasmosis on histopathological examination, which was further confirmed by culture examination. The case is reported for the following reasons:

The patient was immunocompetent

The patient belonged to a nonendemic zone

The lesion was ulcerated with a punched-out ulcer and mimicked a malignant ulcer.

Case Report

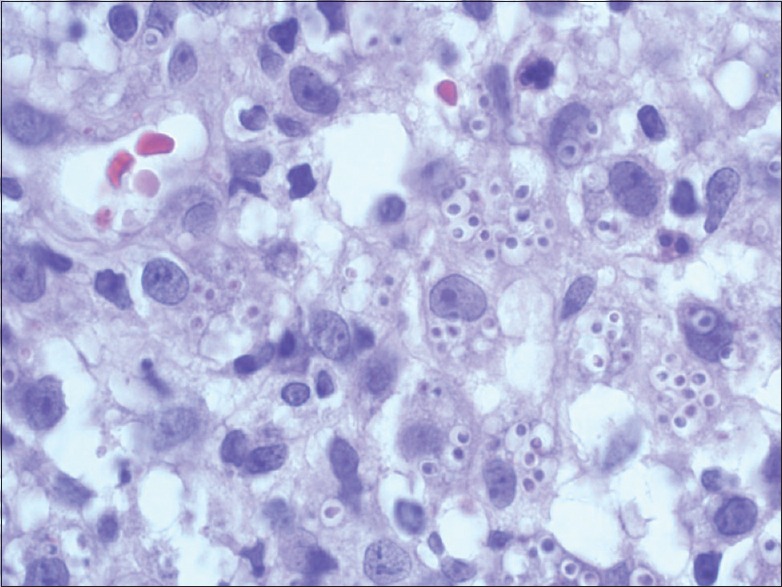

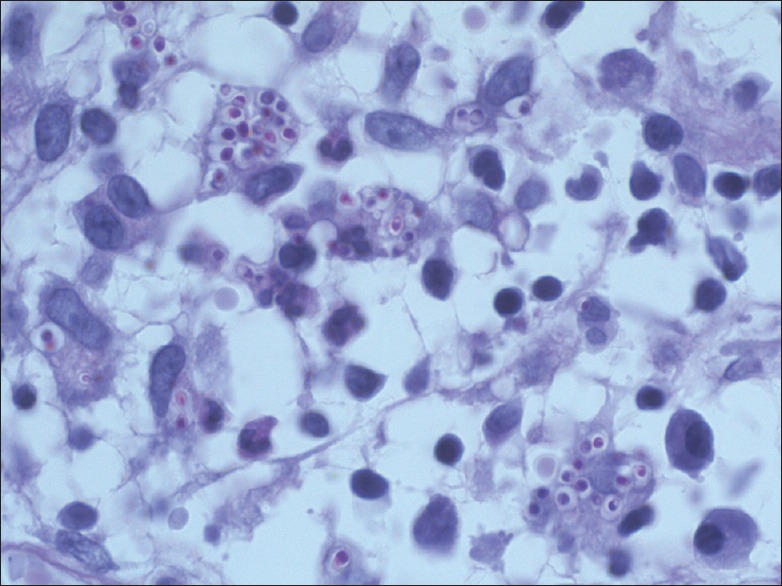

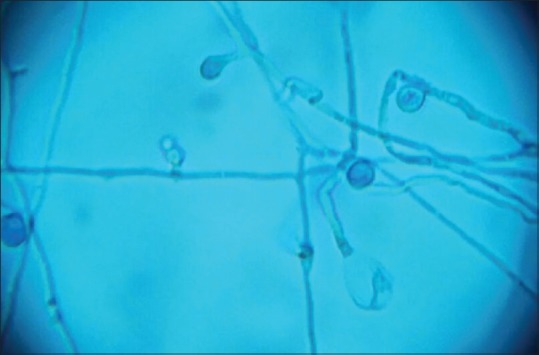

A 32-year-old male presented to the Department of Dermatology with the complaint of a single ulcerated lesion on the right thigh [Figure 1]. He gave the history that it began as a nodule about 0.5 cm in size, 1½ months back which was discolored and nonitching. It remained so for 15–20 days. The patient then developed pain and induration at the site of the lesion that now increased to the size of 3 cm. Soon after, an abscess developed at the site if the lesion that ruptured. Further, he revealed that 6 months back, he met with an accident while riding a motorcycle. The patient did not remember any history of thorn manipulation. The patient is a public health worker and is not associated with laboratory work. On local examination, a single well-defined noduloplaque lesion of size 3 cm × 3 cm was observed. The lesion had a central punched-out ulcer of size 1.5 cm × 1 cm and depth 1.5 cm with surrounding healthy granulation tissue. The lesion had well-defined raised margins that were firm in consistency and tender. No regional lymphadenopathy was present. The hemogram was unremarkable. The patient was not on immunosuppresants, and his HIV status was negative. A malignant ulcer was suspected and the tissue biopsy sent to the Department of Pathology for confirmation. A diffuse dermal infiltrate comprising predominantly of histiocytes admixed with plasma cells and few lymphocytes and eosinophils characterized the lesion. The majority of the histiocytes revealed intracellular small (2–3 μm) sized eosinophilic round to ovoid bodies. A clear halo around those organisms was observed [Figure 2]. These bodies were found extracellularly also. Periodic acid-Schiff reaction revealed magenta colored round to oval bodies surrounded with a halo, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous histoplasmosis. The organism took 3 weeks to grow and form colonies on the culture [Figure 3]. On naked eye examination, white cottony growth was obtained on Sabouraud's dextrose agar (plain) at 25°C after a period of 15–20 days. The reverse of the colony was white with yellowish tinge. At 37°C, whitish granular yeast like colony was obtained, which was inhibited by cycloheximide. On microscopy at 25°C, septate hyphae were seen, which bore round smooth macroconidia (7–15 μm in size) arising from conidiophores, sparse microconidia (2–4 μm) could also be seen arising directly from hyphae. At 37°C, 2–4 μm small round budding yeast cells were seen. The microscopic morphology of Histoplasma capsulatum at 25° centigrade showed tuberculate macroconidia (wall showing tiny spiny projections) [Figure 4]. No systemic involvement was detected on further investigations. The patient was put on broad-spectrum antifungals, liposomal amphotericin-B in the dosage of 3 mg/kg body weight daily for 3 weeks. The patient after completion of the treatment was found apparently well with healing of the lesion. The lesion had been excised completely, leaving a scar only. Further, the patient was lost in follow-up. This is probably the 1st time in the literature that a primary cutaneous manifestation of histoplasmosis is being described in an immunocompetent individual.

Figure 1.

Clinical photograph showing an ulcer on the right thigh

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing sheets of macrophages with intracellular and extracellular small (2–3 μm) sized eosinophilic round to ovoid bodies. (HPE, ×1000)

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph showing periodic acid Schiff positive magenta colored ovoid bodies. (PAS, ×1000)

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of culture on Sabaraud's dextrose agar showing whitish mycelial growth. The microscopic morphology of Histoplasma capsulatum at 25° centigrade shows tuberculate macroconidia (wall showing tiny spiny projections) (×400)

Discussion

Histoplasmosis is an endemic mycosis, which is most prevalent in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys of North America though there are rare reports of this myoses from nonendemic regions too.[1,2] There are reports of this disease in both immuno-suppressed as well as immunocompetent host.[3] The causative agent H. capsulatum is found globally in soil, especially in soil containing high concentrations of bird and bat droppings.[4] It occurs mainly in immunocompromised individuals, more so in HIV-infected persons and usually with a CD4 counts <75 cells/μL. The clinical spectrum is variable, ranging from a severe multisystem illness involving the bone marrow, liver, spleen and lungs, to an indolent infection localized to the gastrointestinal tract, skin, adrenal glands, brain, meninges, or other extrapulmonary tissue. It has two variants: H. capsulatum var. duboisii found in Africa and H. capsulatum var capsulatum found in Latin America and other tropical countries. Lesions of the skin and bones predominate in the African form while pulmonary changes dominate the picture in the other form.[5] Although Panja and Sen first reported histoplasmosis from India in 1959, case reports of the disease have been few and far between.[6] Clinical manifestations of histoplasmosis are of three main types: Pulmonary, progressive disseminated, and chronic cavitary forms.[7] On initial exposure to the fungus, the infection is self-limiting and restricted to lungs in 99% of the individuals while the remaining 1% progress to either disseminated or chronic disease involving the lungs, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow and sometimes the skin and mucous membranes.[8] Skin lesions may occur with all the three forms of histoplasmosis or, rarely, as primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Cutaneous lesions occur in up to 17% of patients with disseminated histoplasmosis and can manifest as papules, pustules, plaques, ulcers, molluscum or wart-like lesions and, rarely, erythema nodosum.[9] Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis is very rare and can present with nodules, ulcers, abscesses or molluscum contagiosum-like lesions.[10] The route of infection is through direct inoculation of spores through the skin and mucous membranes, and thorn pricks are the most common mode of acquiring this variant of histoplasmosis. Systemic antifungal treatment is indicated for severe acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, progressive disseminated histoplasmosis, and any manifestation in an immunocompromised patient.

Diagnostic modalities include cultures, fungal stains of tissue or body fluids and tests for antigens and antibodies. Serologic tests for antibodies provide the basis for diagnosis in patients with mild infections, but require at best a month to appear after the initial exposure. Histoplasmin skin testing is not recommended for diagnostic purposes because of the high rate of positive reactions in endemic areas and variable duration of responses to the skin test. Antibody detection tests such as complement fixation, DNA probes and radioimmunoassays are successful, but can be performed only in very few sophisticated centers. Detection of polysaccharide antigen in serum, urine, or bronchoalveolar lavage in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis is a rapid and specific diagnostic method. Culture can be made from infective material such as blood, bone marrow or sputum, and they should be observed for 6–8 weeks before they may be considered negative. When a biopsy is possible, sections of enlarged lymph nodes or tissues from splenic or hepatic puncture may show endothelial cells packed with histoplasma capsulatum.

A skin biopsy can prove to be useful in establishing the diagnosis especially in set up like ours where facilities for serodiagnosis are not readily available. Also, most of these tests would be of little or no use in cases of pure cutaneous histoplasmosis.

Although excellent laboratory methods are available, histoplasmosis in nonendemic regions, might pose a diagnostic challenge. Physicians must be aware of the clinical syndromes and take advantage of the epidemiologic clues, namely activities or occupations that expose the patient to sites contaminated that expose the patient to sites contaminated with bat or bird droppings. Also, clinicians must be familiar with the uses and limitations of the diagnostic tests for fungal diseases.

The various drugs employed in treatment are amphotericin, ketoconazole, itraconazole and terbinafine, of which itraconazole is the drug of choice, except in severe systemic involvement, where amphotericin is preferred.[11]

Our patient had many unique characteristics. First, primary cutaneous histoplasmosis in immunocompetent individuals is itself extremely rare. Second, the skin lesions mimicked a malignant ulcer with raised everted margins which further added to the diagnostic dilemma. Another interesting fact was that the lesion was solitary with no systemic involvement. Such a condition in an immunocompetent individual has probably not been reported in the literature earlier.

Conclusion

Histoplasmosis is an opportunistic fungal infection occurring more commonly in immune-suppressed individuals. It has varied presentations, including pulmonary, progressive disseminated, chronic cavitary, and primary cutaneous forms. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis is a very rare condition, and we have hereby reported such a case in an immunocompetent individual.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

We have seen a case of primary cutaneous histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent individual from a nonendemic region which presented as an ulcerated skin lesion having raised everted margins thus mimicking a malignant ulcer.

References

- 1.O’Hara CD, Allegretto MW, Taylor GD, Isotalo PA. Epiglottic histoplasmosis presenting in a nonendemic region: A clinical mimic of laryngeal carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:574–7. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-574-EHPIAN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minamoto GY, Rosenberg AS. Fungal infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:381–409. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70523-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf J, Blumberg HM, Leonard MK. Laryngeal histoplasmosis. Am J Med Sci. 2004;327:160–2. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cano MV, Hajjeh RA. The epidemiology of histoplasmosis: A review. Semin Respir Infect. 2001;16:109–18. doi: 10.1053/srin.2001.24241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singhi MK, Gupta L, Kacchawa D, Gupta D. Disseminated primary cutaneous histoplasmosis successfully treated with itraconazole. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:405–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panja G, Sen S. A unique case of histoplasmosis. J Indian Med Assoc. 1954;23:257–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cirillo-Hyland VA, Gross P. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 1995;55:161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sood N, Gugnani HC, Batra R, Ramesh V, Padhye AA. Mucocutaneous nasal histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent young adult. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:182–4. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.32743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sayal SK, Prasad PS, Mehta A, Sanghi S. Disseminated histoplasmosis: Cutaneous presentation. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:90–1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair SP, Vijayadharan M, Vincent M. Primaty cutaneous histoplasmosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2000;66:151–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer RD. Treatment of fungal infections in patients with HIV-infection or AIDS. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1994;281:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80630-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]