Abstract

Background

Hyponatremia is prognostic of higher mortality in some cancers but has not been well studied in others. We used a longitudinal design to determine the incidence and prognostic importance of euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia in patients following diagnosis with lymphoma, breast (BC), colorectal (CRC), small cell lung (SCLC), or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

Medical record and tumor registry data from two large integrated delivery networks were combined for patients diagnosed with lymphoma, BC, CRC, or lung cancers (2002–2010) who had ≥1 administration of radiation/chemotherapy within 6 months of diagnosis and no evidence of hypovolemic hyponatremia. Hyponatremia incidence was measured per 1000 person-years (PY). Cox proportional hazard models assessed the prognostic value of hyponatremia as a time-varying covariate on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

Hyponatremia incidence (%, rate) was 76 % each, 1193 and 2311 per 1000 PY, among NSCLC and SCLC patients, respectively; 37 %, 169 in BC; 64 %, 637 in CRC, and 60 %, 395 in lymphoma. Hyponatremia was negatively associated with OS in BC (HR 3.7; P = <.01), CRC (HR 2.4; P < .01), lung cancer (HR 2.4; P < .01), and lymphoma (HR 4.5; P < .01). Hyponatremia was marginally associated with shorter PFS (HR 1.3, P = .07) across cancer types.

Conclusions

The incidence of hyponatremia is higher than previously reported in lung cancer, is high in lymphoma, BC, and CRC and is a negative prognostic indicator for survival. Hyponatremia incidence in malignancy may be underestimated. The effects of hyponatremia correction on survival in cancer patients require further study.

Keywords: Hyponatremia, Euvolemic, Hypervolemic, Cancer, Survival

Background

Hyponatremia, the most common electrolyte disturbance in hospitalized patients, results from loss of body sodium or potassium with secondary water retention (hypovolemic); from relative or absolute excess of body water (euvolemic, including syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH)); and from edema formation due to renal sodium and water retention (hypervolemic) [1, 2]. Hypovolemic hyponatremia responds readily to volume repletion, while treatment modalities in euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia are not well standardized [1]. Hyponatremia incidence and prevalence vary greatly depending on the population, the presence and type of malignancy, clinical setting, and serum sodium cutoff point [3–5]. Its prevalence has been reported in 1.7 % of the general United States (US) population and in 3.4 % of respondents who identified themselves as having cancer [2]. Hyponatremia incidence in cancer patients has been reported in as many as 47 % of hospital admissions, [6] and the frequency of moderate to severe hyponatremia in hospitalized patients can range from 24 to 50 %, depending on malignancy type [7].

To date, most studies of hyponatremia in cancer have been performed primarily in hospitalized patients or in patients after the occurrence of another clinical event, eg, surgical resection, chemotherapy initiation [6–9]. These studies have largely been conducted in patients with lung or hematologic cancers or as an analysis of multiple cancer types in studies assessing the prognostic effects of hyponatremia. However, little research has been conducted in other highly prevalent cancers, such as breast or colorectal cancer. Moreover, to our knowledge, no study has examined the frequency and prognostic impact of hyponatremia longitudinally, beginning with the date of cancer diagnosis. The current study assessed the incidence and prognostic importance of euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia on or after diagnosis with breast cancer (BC), colorectal cancer (CRC), small cell lung cancer (SCLC), non-SCLC (NSCLC), and lymphoma (Hodgkins, non-Hodgkins).

Methods

Study design

This retrospective cohort analysis combined medical record and tumor registry data from two large, integrated delivery networks (IDN) serving patients in the Midwest (IDN 1) and MidAtlantic (IDN 2) regions of the US. Both are not-for-profit, physician-led IDNs, which together contain data for more than 7 million patients. Patient anonymity and confidentiality were preserved by de-identification of the database in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. For IDN 1, the protocol was approved by an institutional review board (IRB) and for IDN 2, the production and delivery of de-identified data was deemed exempt from IRB review.

Patients

Patients selected into the study were adults with BC, CRC, SCLC, NSCLC, or lymphoma documented in their respective cancer registry between December 1, 2002 and November 30, 2010 (IDN 1) or January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009 (IDN 2), provided that the cancer stage was known, the patient met analytic case requirements, and had ≥1 administration of radiation or chemotherapy ≤6 months of diagnosis. In addition, patients were required to meet continuous enrollment thresholds in IDN1 (12 months prior to and ≥1 month post cancer diagnosis) or continuous clinical activity thresholds in IDN 2 (≥1 in-system contacts in the 12 months prior to and ≥3 in the 6 months post cancer diagnosis). Patients who had insufficient or conflicting documentation in their medical records, had registration of a non-invasive tumor, received cancer-related therapy outside of the IDN, or had hypovolemic hyponatremia were excluded. Patients were followed until study end, death, clinical trial entry, new primary cancer onset, disenrollment (IDN 1), or end of continuous clinical activity (IDN 2).

Analysis

The cohort was divided into patients who developed one or more episodes of hyponatremia at any time during follow-up and those who never developed hyponatremia during follow-up. Hyponatremia, defined as a serum sodium laboratory result ≤135 mEq/L, was captured as a time-varying covariate since it could resolve and then reoccur. A hyponatremia episode began on the first abnormal test result date and was considered resolved on the first of 2 subsequent normal results. Hyponatremia incidence was measured per 1000 person years (PY) of observation and reported with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs).

Hyponatremia was classified as mild (131–135 mEq/L), moderate (125–130 mEq/L), or severe (<125 mEq/L) based on the lowest observed serum sodium value during the episode and was then further classified as euvolemic, hypervolemic, or hypovolemic based on a multi-stage algorithm using existing electronic laboratory data, medication orders, and ICD-9-CM diagnosis files. The first stage of the algorithm, which has not yet been validated, identified cases of true hyponatremia based on serum osmolality test results of <275 mOsm/kg ≤48 h of the serum sodium result with no evidence of hyperglycemia. The algorithm then divided patients into hypovolemic, hypervolemic or euvolemic hyponatremia decision trees based on ICD 9 CM diagnosis codes, disease history, and urine osmolality values. The algorithm further segmented euvolemia into “SIADH,” largely determined by laboratory values, and “other euvolemic hyponatremia,” assigned to patients that did not meet the criteria for hypervolemic but had a history of hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiencies, psychogenic polydipsia, or diuretic use.

Patient demographics were captured as of the date of cancer diagnosis. Baseline clinical characteristics were captured during the 12 months prior to cancer diagnosis. A 3-point universal performance status score (PS) combined Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scores [10]. Grade 1 PS (good) was comprised of ECOG PS 0–1 and KPS 80–100; Grade 2 PS (fair) of ECOG PS 2 and KPS 60–70; and Grade 3 PS (poor) of ECOG PS 3–4 and KPS 10–60. The statistical significance of between-cohort differences in categorical variables was evaluated using the chi-square test. Continuous data were compared using the t-test. All tests were two-tailed, with a significance level of p < 0.05.

The primary study outcome was overall survival (OS). Mortality was ascertained from registry records and state death records. The secondary study outcome, progression free survival (PFS), was recorded and reported for IDN1 only due to resource constraints. The definition for solid tumor progression, modified from RECIST v1.1., [11] included: recurrence in a disease-free person, stage progression in a patient with active disease, increase in existing lesion size, occurrence of a new lesion, and “other.” Disease progression in lymphoma, using Cheson criteria, [12] included: occurrence of a new lesion, increase in positron emission tomography uptake, increase in lymph node or lesion size, recurrence in a disease free person, and “other.”

Survival in days was calculated separately for OS and PFS, from the date of cancer diagnosis to the date of all cause death (OS) or progression (PFS) in patients with the event and until the first evidence of censoring or study end for patients who were not known to have died or to have experienced progression by the end of the study. Kaplan-Meier life tables were used to estimate survival at 1, 3, and 5 years. A Cox Proportional Hazard model with hyponatremia as a time-varying covariate was employed to identify the independent prognostic factors associated with an increased risk of death across all cancer types and among patients in each individual cancer type.

Results

Patients

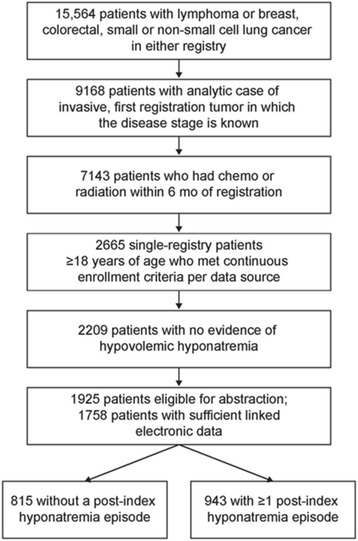

During accrual of the study sample (detailed in Fig. 1), 1758 patients met all study requirements from a pool of 15,564 patients in both IDNs. It should be noted that 456 patients with hypovolemic hyponatremia (3 %) were excluded from the study because this type of hyponatremia generally responds to treatment with intravenous fluids, while hypervolemic and euvolemic hyponatremia tend to be more difficult to diagnose and treat [1, 4, 13]. Additionally, intravenous hydration is often required for many cancer therapies and its use may complicate analysis in patients with hypovolemic hyponatremia [4]. Among study-eligible patients, 71 % were female, with a mean (SD) age of 60 (13.0) years and a mean (SD) follow-up duration of 3.1 (2.7) years. Selected characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Patients who developed hyponatremia on or after cancer diagnosis were more likely to be male, white, and have a shorter follow-up time (Table 1). They were also significantly more likely to have lung cancer or CRC and less likely to have BC. Across tumor types, the hyponatremic cohort was more likely to have metastatic disease and a worse performance status after cancer diagnosis.

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Number of patients | Total | No hyponatremia episode | ≥1 hyponatremia episode | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1758 | n = 815 | n = 943 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Sex, n (%) | <0.01 | |||

| Male | 503 (29) | 145 (18) | 358 (38) | |

| Female | 1255 (71) | 670 (82) | 585 (62) | |

| Age group collapsed, n (%) | 0.06 | |||

| 18–64 | 1108 (63) | 533 (65) | 575 (61) | |

| ≥65 | 650 (37) | 282 (35) | 368 (39) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 60.2 (13) | 59.6 (13) | 60.6 (13) | 0.11 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.09 | |||

| Asian | 18 (1) | 8 (1) | 10 (1) | |

| Black | 340 (19) | 179 (22) | 161 (17) | |

| White | 1393 (79) | 627 (77) | 766 (81) | |

| Median household income, n (%) | 0.16 | |||

| ≤$49,999 | 1030 (59) | 480 (59) | 550 (58) | |

| $50,000–$69,999 | 460 (26) | 197 (24) | 263 (28) | |

| ≥$70,000 | 239 (14) | 123 (15) | 116 (12) | |

| Diagnosis year, n (%) | 0.02 | |||

| 2002–2004 | 270 (15) | 146 (18) | 124 (13) | |

| 2005–2007 | 869 (49) | 386 (47) | 483 (51) | |

| 2008–2010 | 619 (35) | 283 (35) | 336 (36) | |

| Mean length of follow-up, y (SD) | 3.1 (3) | 3.3 (3) | 3.0 (3) | 0.03 |

| Clinical characteristics at baseline | ||||

| Cancer type, n (%) | ||||

| Breast | 839 (48) | 533 (65) | 306 (32) | <0.01 |

| Colorectal | 233 (13) | 84 (10) | 149 (16) | <0.01 |

| Colon | 146 (8) | 50 (61) | 96 (10) | <0.01 |

| Rectal | 87 (5) | 34 (4) | 53 (6) | 0.16 |

| Lung | 485 (28) | 117 (14) | 368 (39) | <0.01 |

| Small cell | 80 (5) | 19 (2) | 61 (7) | <0.01 |

| Non-small cell | 405 (23) | 98 (12) | 307 (33) | <0.01 |

| Lymphoma | 201 (11) | 81 (10) | 120 (13) | 0.07 |

| Hodgkins | 29 (2) | 12 (2) | 17 (2) | 0.59 |

| Non-Hodgkins | 172 (10) | 69 (9) | 103 (11) | 0.08 |

| Distant metastasis, n (%) | 384 (22) | 99 (12) | 285 (30) | <0.01 |

| Any PS within 90 days of diagnosis, n (%) | 864 (49) | 384 (47) | 480 (51) | 0.11 |

| Grade 1: ECOG 0, 1; KPS 80–100a | 747 (87) | 350 (91) | 397 (83) | <0.01 |

| Grade 2: ECOG 2; KPS 60–70a | 78 (9) | 26 (7) | 52 (11) | 0.04 |

| Grade 3: ECOG 3, 4; KPS 10–50a | 39 (5) | 8 (2) | 31 (7) | <0.01 |

| Clinical characteristics during follow-up | ||||

| Distant metastasis, n (%) | 513 (29) | 120 (15) | 393 (42) | <0.01 |

| PS, last observed documentation, n (%) | 1249 (71) | 553 (68) | 696 (74) | <0.01 |

| Grade 1: ECOG 0, 1; KPS 80–100a | 990 (79) | 499 (90) | 491 (71) | <0.01 |

| Grade 2: ECOG 2; KPS 60–70a | 141 (11) | 34 (6) | 107 (15) | <0.01 |

| Grade 3: ECOG 3, 4; KPS 10–50a | 118 (9) | 20 (4) | 98 (14) | <0.01 |

| Hospice services, n (%) | 129 (7) | 21 (3) | 108 (12) | <0.01 |

| First course surgical resection, n (%) | 1029 (62) | 563 (72) | 466 (52) | <0.01 |

| Any chemo and hormonal therapies, n (%) | 1410 (80) | 595 (73) | 815 (86) | <0.01 |

| Alkylating agentsb | 547 (39) | 269 (45) | 278 (34) | <0.01 |

| Antimetabolitesb | 427 (30) | 113 (19) | 314 (39) | <0.01 |

| Antitumor antibioticsb | 452 (32) | 223 (38) | 229 (28) | <0.01 |

| Hormone therapyb | 594 (42) | 318 (53) | 276 (34) | <0.01 |

| Mitotic inhibitorsb | 761 (54) | 260 (44) | 501 (62) | <0.01 |

| Platinum agentsb | 512 (36) | 114 (19) | 398 (49) | <0.01 |

| Targeted therapiesb | 375 (27) | 124 (21) | 251 (31) | <0.01 |

| Otherc | 175 (10) | 48 (6) | 127 (13) | <0.01 |

Abbreviations: ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, KPS Karnofsky PS, PS performance status, SD standard deviation, y year

aPercent of patients with any PS

bPercent of patients with any chemo or hormonal therapy

cOther treatments including immunotherapies and topoisomerases

Hyponatremia incidence

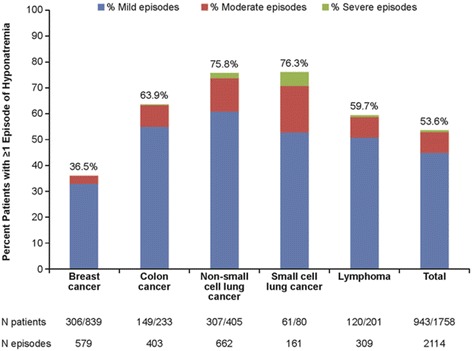

Across cancer types, 54 % had ≥1 episode of euvolemic or hypervolemic hyponatremia episode (Fig. 2). The frequency of hyponatremia was highest among patients with NSCLC and SCLC (76 % each), and lowest among patients with BC (37 %). The majority (84 %) of all hyponatremia episodes were mild. The incidence rate (IR) of hyponatremia per 1000 PY was 385.5 (95 % CI, 369.2–402.2), with individual rates of 169 (BC), 395 (lymphoma), 637 (CRC), 1193 (NSCLC), and 2311 (SCLC). The mean (SD) number of hyponatremia episodes per patient was 2.2 (1.9), ranging from a low of 1.9 in BC to a high of 2.7 in CRC. Median time to first hyponatremia episode was 59 days, ranging from a low of 10 days in SCLC to a high of 194 days in BC. Median duration of each hyponatremia episode was 16 days.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of patients with hyponatremia, by hyponatremia severity and cancer type

Across all cancer types, 284 patients (16 %) had ≥1 moderate or severe episode of hyponatremia. Moderate or severe episodes occurred in 6 % of BC patients, 19 % of both CRC and lymphoma patients, 27 % of NSCLC patients, and 46 % of SCLC patients. Among patients with ≥1 moderate or severe hyponatremia episode, 58 % of hyponatremia episodes were mild, 37 % were moderate, and 6 % were severe. The mean (SD) number of hyponatremia episodes per patient was 2.9 (2.4), ranging from 2.4 for both BC and NSCLC to 3.9 for CRC. Median time to first hyponatremia episode was 19 days, ranging from 4 days for SCLC to 105 days for BC. Mean duration of each hyponatremia episode ranged from 41 days for patients with SCLC to 130 days for patients with BC.

Survival analysis

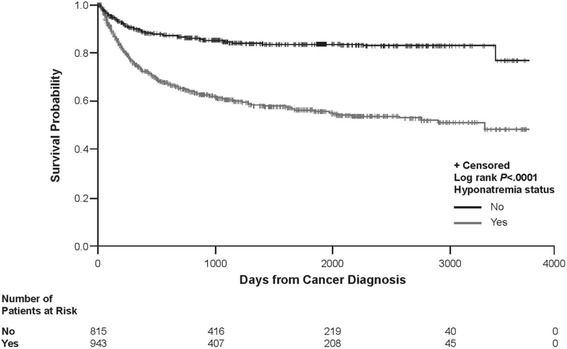

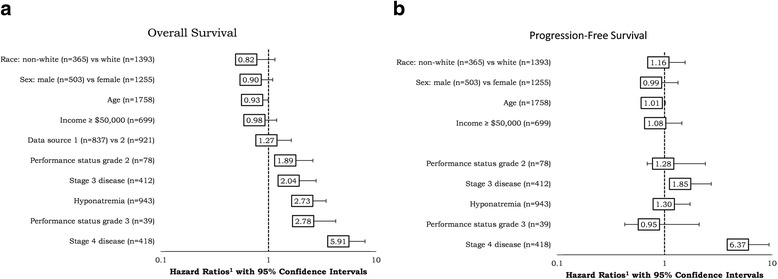

Across the studied cancer types, 27 % of patients died during follow-up. SCLC patients had the highest proportion of deaths at 86 % whereas BC patients had the lowest at 5 %. Life table data presented in Table 2 characterizes OS, by cancer type, at 1, 3, and 5 years. The Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves, across all cancer types, are shown in Fig. 3. Cox model results are presented graphically in Fig. 4a and 4b. Experiencing one or more episodes of hyponatremia was associated with a significant increase in the likelihood of death (HR 2.7, 95 % CI, 2.2–3.4; P < 0.01), as was having stage 3 (HR 2.0, 95 % CI, 1.5–2.7; P < 0.01) or stage 4 disease at diagnosis (HR 5.9, 95 % CI, 4.4–7.9; P < 0.01), having a fair/poor PS score at diagnosis (HR 2.8, 95 % CI, 1.8–4.2; P < 0.01), or having an unknown PS at the time of diagnosis (HR 1.5, 95 % CI, 1.2–1.8; P < 0.01). Developing hyponatremia was associated with significantly increased likelihood of death in each cancer specific model, except for SCLC: BC (HR 3.7, 95 % CI, 1.9–7.2; P < 0.01), CRC (HR 2.4, 95 % CI, 1.3–4.7; P < 0.01), lung cancer (HR 2.4, 95 % CI, 1.8–3.2; P < 0.01), SCLC (HR 1.5, 95 % CI 0.82–2.8; P = 0.19), NSCLC (HR 2.8, 95 % CI 2.0–3.9; P < 0.01) and lymphoma (HR 4.5, 95 % CI, 1.8–11.5; P < 0.01) (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Life tables depicting overall survival at 1, 3, and 5 years

| Cancer type | 1 year | 3 year | 5 year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS, % | All | HN | No HN | All | HN | No HN | All | HN | No HN |

| All cancer types | 81 | 64 | 87 | 72 | 49 | 81 | 69 | 45 | 79 |

| Breast cancer | 98 | 95 | 99 | 97 | 92 | 97 | 94 | 89 | 95 |

| Colorectal cancer | 86 | 79 | 90 | 73 | 65 | 78 | 68 | 56 | 76 |

| Colon cancer | 85 | 78 | 88 | 69 | 62 | 72 | 63 | 53a | 72 |

| Rectal cancer | 87 | 80 | 92 | 81 | 68 | 89 | 75 | 62a | 85a |

| Lung cancer | 45 | 39 | 51 | 22 | 16 | 29 | 17 | 11a | 24 |

| Non-small cell | 49 | 39 | 56 | 26 | 18 | 32 | 19 | 12a | 27 |

| Small cell | 30 | 40 | 18a | 6a | 6a | 8a | 6a | 6a | 8a |

| Lymphoma | 87 | 79 | 92 | 84 | 71 | 91 | 82 | 67 | 91 |

| Hodgkins | 100 | 100a | 100 | 96 | 88a | 100 | 96a | 88a | 100a |

| Non-Hodgkins | 85 | 76 | 91 | 82 | 68 | 89 | 80 | 64 | 89 |

Abbreviation: HN hyponatremia

aEffective sample size for the year in question is ≤10 patients

Fig. 3.

Kaplan Meier plot of overall survival across cancer types

Fig. 4.

Overall survival and progression-free survival across cancer types

Twenty-five percent (n = 228) of patients in IDN 1 experienced disease progression during follow-up, ranging from a low of 10 % in BC to a high of 65 % in SCLC. Mean (SD) time to progression was 395 (512) days, shortest in SCLC patients at 160 days and longest in patients with BC at 763 days. PFS at 1, 3, and 5 years was 87, 81, and 78 %, respectively. Cox model results are presented in Fig. 3. Experiencing one or more episodes of hyponatremia was not associated with a significant change in PFS (HR 1.3, 95 % CI, 0.98–1.7; P = 0.07); however, patients with stage 3 (HR 1.8 95 % CI, 1.3–2.7; P < 0.01), or stage 4 cancer at diagnosis (HR 6.4 95 % CI, 4.3–9.4; P < 0.01) were at increased likelihood to experience disease progression.

Discussion

This study combined administrative and medical record data from two large healthcare delivery systems in the US to ascertain the incidence of hypervolemic or euvolemic hyponatremia after cancer diagnosis and to assess its prognostic importance on OS and PFS. Study findings suggest that the incidence of hyponatremia among patients with NSCLC and SCLC is higher than previously reported, that the incidence of hyponatremia in BC, CRC, and lymphoma is high, and that the occurrence of hyponatremia in all 4 types of cancer is a negative prognostic indicator.

The incidence of hyponatremia in cancer patients varies greatly depending on cancer type, clinical setting, and the serum sodium threshold employed [3–5, 14]. Malignancy-related SIADH due to ectopic secretion of arginine vasopressin manifesting as euvolemic hyponatremia is most commonly seen in patients with SCLC, but can also be associated with other malignancy types [3–5]. In addition, antineoplastic and cancer therapy palliative drugs are also known to cause hyponatremia and many are directly associated with SIADH [3–5]. Other underlying conditions, such as pain and nausea, or routine hospital treatments may also cause hyponatremia, contributing to disease complexity.

Study findings suggest that the hyponatremia incidence among patients with lung cancer is higher than previous reported. Hyponatremia occurred in 76 % of lung cancer patients in the current study, considerably higher than 20–50 %, as previously reported [7, 15–18]. This difference in incidence may be greater than observed because the current study excluded patients with hypovolemic hyponatremia, while previously published studies did not. However, previous studies also characterized hyponatremia incidence upon the occurrence of a specific clinical event such as hospitalization, surgical resection or chemotherapy. As such, the measurement of hyponatremia in these studies did not include hyponatremia in patients who did not experience the study-qualifying event (eg resection), or who experienced hyponatremia prior to the qualifying event. Differences in incidence between SCLC and NSCLC subgroups did exist in the current study. Forty-six percent of SCLC patients experienced an episode of moderate/severe hyponatremia (vs 27.4 % NSCLC) with the IR per thousand PY almost twice as high among SCLC patients (2311 vs 1193).

Results from the current study also suggest that hyponatremia incidence in patients with CRC, lymphoma, and BC is noteworthy, occurring in 64, 60, and 36 % of patients at an IR per 1000 PY of 637, 395, and 169, respectively. While most hyponatremia episodes in these patients were mild, moderate to severe hyponatremia occurred in 19 % of CRC and lymphoma patients and in 6 % of BC cases. As was observed in lung cancer, hyponatremia incidence is higher in this study than has been previously reported, ie, 24 % of BC, 27 % of lymphoma and 28 % of CRC patients [7, 19].

Hyponatremia has been correlated with shorter survival in a number of studies, although too few studies have been conducted in a given cancer type to support meta-analyses [3, 7, 17–21]. The current study adds to the growing body of literature in lung cancer and lymphoma, and helps to establish preliminary results in CRC and BC. Current study findings confirm the prognostic importance of hyponatremia in lung cancer. The hazard ratio (95 % CI, P value) associated with hyponatremia in the OS lung cancer model was 2.4 (1.8–3.2, P < 0.01). Findings in the SCLC specific model did not reach statistical significance, but these were constrained by sample size. Findings in the NSCLC-specific model were significant and are generally higher than those previously reported [3, 21]. The current study is also one of the first to establish the prognostic importance of hyponatremia on OS in lymphoma, CRC, and BC. A recent CRC study concluded that patients with mild (HR 1.7), moderate (HR 2.2), and severe (HR 2.2) hyponatremia upon hospitalization had significantly shorter survival (P < 0.001) [19]. These findings are also consistent with a recent meta-analysis which evaluated the prognostic importance of the correction of hyponatremia across a variety of clinical conditions, including all forms of malignancy [22].

Study findings also suggest that hyponatremia may impact PFS. However, PFS was collected only at a single research site and model development, across cancer types, was constrained by sample size and number of events. However, our results are consistent with a study by Tiseo et al. of hyponatremia in SCLC, in which PFS in the univariate model did not meet significance, but did show a trend of correlation between hyponatremia and PFS (HR = 1.23, 95 % CI 0.97–1.55; P = 0.085) [21].

Although hyponatremia is associated with a poorer prognosis in cancer patients, as in other diseases, there are still questions as to whether hyponatremia is a marker of disease severity, as evidenced in studies in palliative-care patients, [8, 23] or if correction of hyponatremia can lead to overall patient benefits, including survival [24–26]. A recent meta-analysis has suggested that correction of hyponatremia improves survival, particularly in patients who are corrected >130 mEq/L [22]. Additionally, findings from a subsequent study suggest that correction of sodium level in cancer patients with severe hyponatremia facilitates additional treatment, and results in significantly greater OS, although the authors note that a causal relationship could not be established [20]. Little is known about the actual mechanism by which hyponatremia influences a poorer prognosis. Underlying renal and/or endocrine dysfunction, more aggressive biological behavior of cancer cells that produce antidiuretic hormone (ADH), and the effects of higher than normal levels of ADH overall are all plausible potential explanations. Although our study suggests that hyponatremia is an adverse prognostic factor in a multivariate statistical analysis, it is unclear if hyponatremia is the result of multiple pathophysiological effects, or an independent biological factor. Additional research is needed to further elucidate these theories.

While the study sample was comparatively large, it was not a random sample and the sources of the data are worth reviewing. Although IDN1 and IDN2 each represent geographically constrained areas, they represent care delivered by some of the largest and best delivery networks within the US. Results, as such, may not generalize to care provided in other areas of the US, from smaller delivery networks or those not associated with academic medical centers. The IDN1 sample only included members of their wholly owned insurance plan and excluded Medicaid patients and the uninsured. While IDN2 patients were not restricted based on payer, it is possible that data capture may have been incomplete if out of network care was not documented. In addition, the classification of hyponatremia type was assigned using a multi-stage algorithm, which has not yet been validated. Accordingly, it is possible that patients excluded from the analysis due to hypovolemic hyponatremia may have been erroneously excluded. It should be further noted that assignment of disease progression was based on modified RECIST 1.1 and Cheson criteria and study results may vary from clinical − trial-based protocols.

Conclusion

It has been shown that the incidence of hyponatremia is high, not only in lung cancer, but also in patients with lymphoma, BC, and CRC. Additionally, the occurrence of hyponatremia in all four types of cancer is associated with poorer OS. An awareness of hyponatremia in cancer is important as it is commonly underestimated by oncologists due to the difficulty of its interpretation [4]. Further studies are warranted to explore the effects of correction of hyponatremia on survival in cancer patients.

Abbreviations

BC, breast cancer; CRC, colorectal cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HR, hazard ratio; IDN, integrated delivery network; IR, incidence rate; IRB, institutional review board; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, performance status; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; SD, standard deviation; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

Acknowledgements

Medical writing and editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript were provided by Scientific Connexions, Inc., Lyndhurst, NJ, USA, an Ashfield Company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, funded by Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA.

Availability of data and materials

The data for this report cannot be shared publically due to the integrated delivery network confidentiality rules as mandated by Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and Health Information Technology for Economic and clinical Health regulations.

Authors’ contributions

JJC, IG, SB, JC, BT, LL, and KS were involved in the conception and design of the study. JJC, BT, LL, and KS collected and assembled study data and BT and LL provisioned study materials and patients. JJC, IG, SB, JC, BT, LL and KS provided data analysis and interpretation. BT, LL, and KS provisioned study materials and patients. JJC, SB, JC, BT, and KS contributed to manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Jorge Castillo is a consultant to Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc, and has received grants from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Pharmacyclics, Inc. and Gilead Sciences. Ilya Glezerman is a consultant to Otsuka and Amgen, Inc.; his spouse is an employee of and owns stock in Pfizer. Joseph Chiodo is an employee of Otsuka and Susan Boklage was an employee at the time of the study. Beni Tidwell and Kathy Schulman are employees of Outcomes Research Solutions, Inc, which received funds from Otsuka to conduct this study. Lois Lamerato is an employee of Henry Ford who received funds from Outcomes Research Solutions to conduct this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Medical record and tumor registry data from two large, integrated delivery networks (IDN) were used for this study. Patient anonymity and confidentiality were preserved by de-identification of the database in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. For IDN 1, the protocol was approved by an institutional review board (IRB) from the Henry Ford Health System and for IDN 2, the production and delivery of de-identified data was deemed exempt from IRB review because access to the data was through a previously prepared commercial dataset. Patient consent was deemed unnecessary because the dataset was sold by a subsidiary of the IDN and as such, has already met HIPAA/Health Information Technology for Economic and clinical Health regulations.

Contributor Information

Jorge J. Castillo, Phone: 617-632-6045, Email: jorgej_castillo@dfci.harvard.edu

Ilya G. Glezerman, Email: glezermi@mskcc.org

Susan H. Boklage, Email: Susan.boklage@gmail.com

Joseph Chiodo, III, Email: Joseph.ChiodoIII@otsuka-us.com.

Beni A. Tidwell, Email: Beni.tidwell@orsolutionsinc.com

Lois E. Lamerato, Email: LLAMERA1@hfhs.org

Kathy L. Schulman, Email: Kathy.schulman@orsolutionsinc.com

References

- 1.Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenburg A, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatremia: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2013;126:S1–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohan S, Gu S, Parikh A, Radhakrishnan J. Prevalence of hyponatremia and association with mortality: results from NHANES. Am J Med. 2013;126(12):1127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castillo JJ, Vincent M, Justice E. Diagnosis and management of hyponatremia in cancer patients. Oncologist. 2012;17:756–65. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Platania M, Verzoni E, Vitali M. Hyponatremia in cancer patients. Tumori. 2015;101(2):246–8. doi: 10.5301/tj.5000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosner MH, Dalkin AC. Electrolyte disorders associated with cancer. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21:7–17. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doshi SM, Shah P, Lei X, et al. Hyponatremia in hospitalized cancer patients and its impact on clinical outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:222–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abu Zeinah GF, Al-Kindi SG, Hassan AA, Allam A. Hyponatraemia in cancer: association with type of cancer and mortality. Eur J Cancer Care. 2014;24(2):224–31. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsunuma R, Tanbo Y, Asai N, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with terminal stage lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:189–94. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hampshire PA, Welch CA, McCrossan LA, et al. Admission factors associated with hospital mortality in patients with haematological malignancy admitted to UK adult, general critical care units: a secondary analysis of the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care. 2009;13:R137. doi: 10.1186/cc8016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M. Karnofsky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: a prospective, longitudinal study of 536 patients from a single institution. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(7):1135–41. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: The Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De las Penas R, Escobar Y, Henao F, et al. SEOM guidelines on hydroelectric disorders. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16:1051–9. doi: 10.1007/s12094-014-1234-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis MA, Hendrickson AW, Moynihan TJ. Oncologic emergencies: pathophysiology, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:287–314. doi: 10.3322/caac.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermes A, Waschki B, Reck M. Hyponatremia as a prognostic factor in small cell lung cancer--a retrospective single institution analysis. Respir Med. 2012;106:900–4. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sengupta A, Banerjee SN, Biswas NM, et al. The incidence of hyponatremia and its effect on the ECOG performance status among lung cancer patients. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(8):1678–82. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5900.3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarzecka M, Kubicki P, Kozielski J. Hyponatremia- evaluation of prevalence in patients hospitalized in the pulmonary department and prognostic significance in lung cancer patients. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;81:18–24. doi: 10.5603/PiAP.2014.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berardi R, Caramanti M, Castagnani M, et al. Hyponatremia is a predictor of hospital length and cost of stay and outcome in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(10):3095–101. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2683-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi JS, Bae EH, Ma SK, et al. Prognostic impact of hyponatremia in patients with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:409–16. doi: 10.1111/codi.12878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balachandran K, Okines A, Gunapala R, et al. Resolution of severe hyponatremia is associated with improved survival in patients with cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:163. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiseo M, Buti S, Boni L, et al. Prognostic role of hyponatremia in 564 small cell lung cancer patients treated with topotecan. Lung Cancer. 2014;86:91–5. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corona G, Giuliani C, Verbalis JG, et al. Hyponatremia improvement is associated with a reduced risk of mortality: evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon J, Ahn SH, Lee YJ, Kin C-M. Hyponatremia as an independent prognostic factor in patients with terminal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1735–40. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schrier RW, Sharma S, Shchekochikhin D. Hyponatraemia: more than just a marker of disease severity? Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:37–50. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chawla A, Sterns RH, Nigwekar SU, Cappuccio JD. Mortality and serum sodium: Do patients die from or with hyponatremia? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(5):960–5. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10101110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fakhouri F, Lavainne F, Karras A. Hyponatremia and mortality in patients with cancer: the devil is in the details. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:168–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this report cannot be shared publically due to the integrated delivery network confidentiality rules as mandated by Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and Health Information Technology for Economic and clinical Health regulations.