ABSTRACT

We previously described 4Dm2m, an exceptionally potent broadly neutralizing CD4-antibody fusion protein against HIV-1. It was generated by fusing the engineered single human CD4 domain mD1.22 to both the N and C termini of the human IgG1 heavy chain constant region and the engineered single human antibody domain m36.4, which targets the CD4-induced coreceptor binding site of the viral envelope glycoprotein, to the N terminus of the human antibody kappa light chain constant region via the (G4S)3 polypeptide linkers. However, therapeutic use of 4Dm2m was limited by its short in vivo half-life. Here, we show that a combination of three approaches have successfully increased the persistence of 4Dm2m in mice. First, to stabilize the scaffold, we enhanced heterodimerization between the heavy chain constant domain 1 (CH1) and kappa light chain constant domain (CK) by using structure-guided design and phage-display library technologies. Second, to address the possibility that long polypeptide linkers might render fusion proteins more susceptible to proteolysis, we shortened the (G4S)3 linkers or replaced them with the human IgG1 hinge sequence, which is naturally designed for both flexibility and stability. Third, we introduced two amino acid mutations into the crystallizable fragment (Fc) of the scaffold previously shown to increase antibody binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) and prolong half-lives in vivo. Collectively, these approaches markedly increased the serum concentrations of 4Dm2m in mice while not affecting other properties of the fusion protein. The new 4Dm2m variants are promising candidates for clinical development to prevent or treat HIV-1 infection. To our knowledge, this is the first report on stabilized CH1-CK, which is potentially useful as a new heterodimerization scaffold for generation of bispecific and multispecific antibodies or proteins with a more favorable pharmacokinetic profile.

KEYWORDS: 4Dm2m, antibody, CH1-CK, fusion proteins, FcRn, HIV-1, heterodimerization, linker, pharmacokinetics, soluble CD4

Introduction

The discovery of highly potent broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies (bnAbs) and the recent demonstration of their therapeutic efficacy in controlling viremia in HIV-1-infected persons have renewed interest in utilizing passive immunization as an effective approach to treat or prevent HIV-1 infection.1,2 However, the virus' ability to constantly mutate enables it to generate variants capable of evading immune recognition necessitating treatment either in combination with other antibodies recognizing different epitopes or parallel treatment with antiretroviral drugs to control the infection.3 Bispecific fusion proteins of soluble forms of the HIV-1 primary receptor CD4 (sCD4) with bnAbs 4,5 or mimetics of the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR56 have emerged as novel classes of promising HIV-1 inhibitors. The two moieties bind the viral envelope glycoproteins (Env) cooperatively and with high avidity, leading to exceptionally potent and broad neutralizing activity of the fusion proteins. Linkage of these two moieties to the crystallizable fragment (Fc) of human IgG1 further endows the fusion proteins with Fc-mediated antibody effector functions that have been found to be critical for the in vivo antiviral activity of bnAbs.7,8

4Dm2m is a bispecific multivalent fusion protein composed of the engineered single-domain sCD4 mD1.22 and antibody domain m36.4 that targets the coreceptor binding site of the Env gp120.4,9,10 The epitope of m36.4 is fully formed or exposed only in the presence of CD4 and therefore, mD1.22 and m36.4 synergize with each other in binding and neutralizing HIV-1. Both binding moieties are linked to the human IgG1 constant region via the (G4S)3 linkers and use the heavy chain constant domain 1 (CH1) and kappa light chain constant domain (CK) for heterodimerization (Fig. 1A). mD1.22 was fused not only to the N terminus of CH1 but also to the C terminus of Fc, while m36.4 was fused only to the N terminus of CK. 4Dm2m neutralized all HIV-1 isolates tested in vitro with potency and breadth greater than those of representative bnAbs such as VRC01 and CD4-Ig, a clinically tested Fc-fusion protein of the two-domain sCD4 D1D2.4 However, our preliminary study in mice showed that 4Dm2m had a markedly shorter in vivo half-life than CD4-Ig. In addition to the potential difference in stability and specificity of binding moieties between 4Dm2m and CD4-Ig, we hypothesized that the use of CH1-CK heterodimerization scaffold and multiple long (G4S)3 linkers in 4Dm2m might contribute to the reduced pharmacokinetics because CH1-CK heterodimerization had previously been shown to be inefficient 11 and unstable,12,13 and the (G4S)3 linker may be sensitive to proteolysis. In this study, we demonstrated that the pharmacokinetics of 4Dm2m was improved by stabilizing CH1-CK and modifying the length and composition of the polypeptide linkers. Effects of Fc mutagenesis on neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) binding and pharmacokinetics were also explored. Our results could pave the way to advance 4Dm2m to non-human primate and human clinical testing for the prevention or treatment of HIV-1 infection.

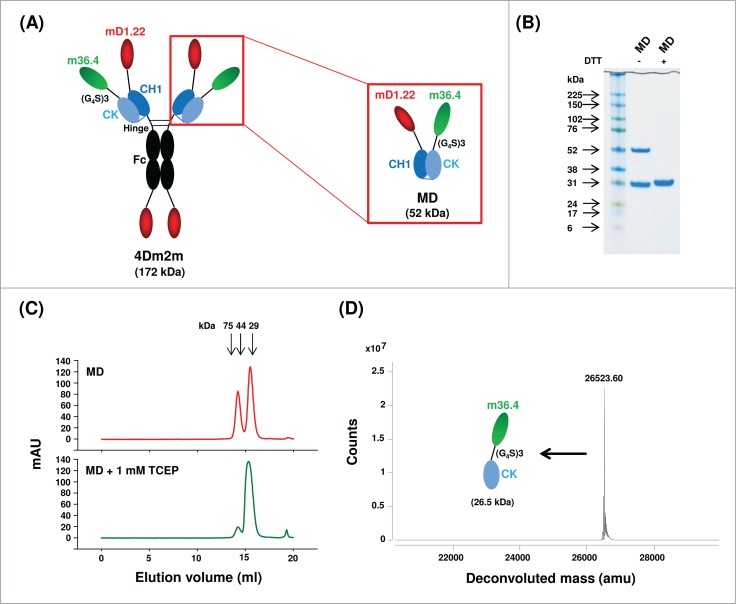

Figure 1.

Inefficient CH1-CK heterodimerization. (A) Schematic representation of 4Dm2m and MD. The short blue line connecting the C termini of CH1 and CK denotes the inter-chain disulfide bridge. Calculated molecular masses are shown in parentheses. (B) Non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE of MD. Molecular masses of standards are shown on the left. (C) Size-exclusion chromatography of MD. The arrows at the top indicate the elution volumes of the molecular mass standards in PBS (pH7.4): carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), ovalbumin (44 kDa), and conalbumin (75 kDa). (D) High-resolution mass spectrometry. Mass spectra were shown with deconvoluted mass for each peak indicated at the top.

Results

Inefficient CH1-CK heterodimerization

CH1-CK had been used as a heterodimerization scaffold to generate bispecific antibodies12 or multivalent fusion proteins.14 However, cooperation between the VH-VL and CH1-CK interface was required for mutual stabilization,15 and, in the absence of VH-VL, CH1-CK failed to yield heterodimeric products in a previous study.11 To evaluate CH1-CK heterodimerization strength in the context of 4Dm2m, we subcloned the N-terminal region of 4Dm2m, resulting in a heterodimeric construct (designated MD) composed of mD1.22-CH1 and m36.4-CK with total calculated molecular weight (cMW) of 52 kDa (Fig. 1A). MD was expressed and affinity purified from the soluble fraction of E. coli periplasm by using a CK-specific ligand. On a non-reducing SDS-PAGE, ∼60% of the purified protein migrated as dissociated mD1.22-CH1 or m36.4-CK monomer with apparent molecular weight (aMW) of 30 kDa, which is larger than their cMWs (25.2 and 26.5 kDa, respectively) (Fig. 1B). Size-exclusion chromatography revealed that, similarly, about 40% of the protein eluted at an aMW comparable to the cMW (52 kDa) of an mD1.22-CH1/m36.4-CK heterodimer, which could be further reduced by 1 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) (Fig. 1C). However, high-resolution mass spectrometry revealed that the purified protein contained m36.4-CK only, with undetectable mD1.22-CH1 (Fig. 1D). These results confirmed the previous finding that CH1-CK heterodimerization was inefficient.11

Improving CH1-CK heterodimerization through structure-guided design and phage-display library technologies

Analysis of the CH1-CK crystal structure (Protein Data Bank entry 1HZH) revealed that hydrophobic interaction at the half (hereafter designated as “upper half”) of the CH1-CK interface closer to the variable domains is weak, while the other half contains many hydrophobic residues (Fig. 2A). We therefore hypothesized that substitution of some amino acid residues at the upper half of the interface with hydrophobic residues might enhance the CH1-CK interaction, leading to more stable heterodimerization. To test this hypothesis, we identified a void structure at the CH1-CK interface that could accommodate bulky amino acid side chains without causing steric clashes. The void is lined by the S64/S66 residues of CH1 and the S69/T71 residues of CK (Fig. 2A). Accordingly, we generated a phage-display library of MD mutants by randomizing the four residues with the degenerate codon NNS, which encodes the complete set of standard amino acids. The library was first cycled through three rounds of panning against the HIV-1 Env gp140SC to enrich clones with preserved binding to the Env. To enrich clones with stable CH1-CK heterodimerization even if the inter-chain disulfide bridge does not form or is interrupted, two additional rounds of selection with a CK-specific ligand were then performed after the resulting phage library was treated with the reducing reagent TCEP (1 and 10 mM for the first and second rounds, respectively) (Fig. 2B).

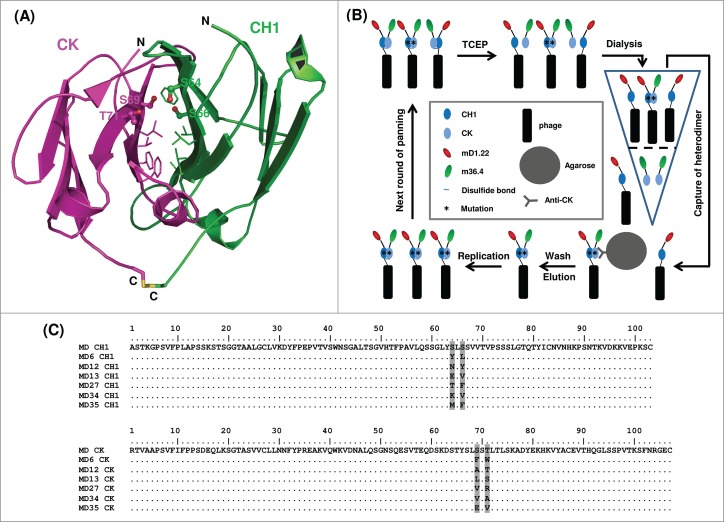

Figure 2.

Design and identification of stabilized CH1-CK. (A) Structural analysis of CH1-CK interface. The side chains of hydrophobic residues at the interface are shown in slim stick representation. The four amino acid residues lining a void structure are indicated with their side chains shown in bold ball-and-stick representation. N and C denote the N and C termini, respectively, of CH1 and CK. (B) Phage-display library panning for enrichment of stabilized CH1-CK. The triangle on the right represents a centrifugal filter with a cut-off of 100 kDa. All other figure elements are defined in the legend (centered rectangle). (C) Selection of stabilized CH1-CK. The amino acid sequences of selected CH1 and CK variants are aligned and numbered. Mutations from the wild-type sequences are highlighted with gray shading.

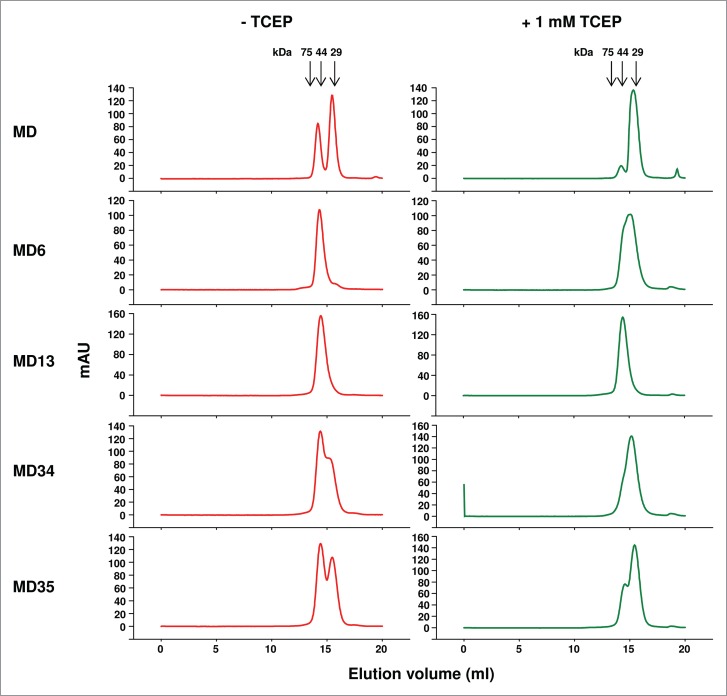

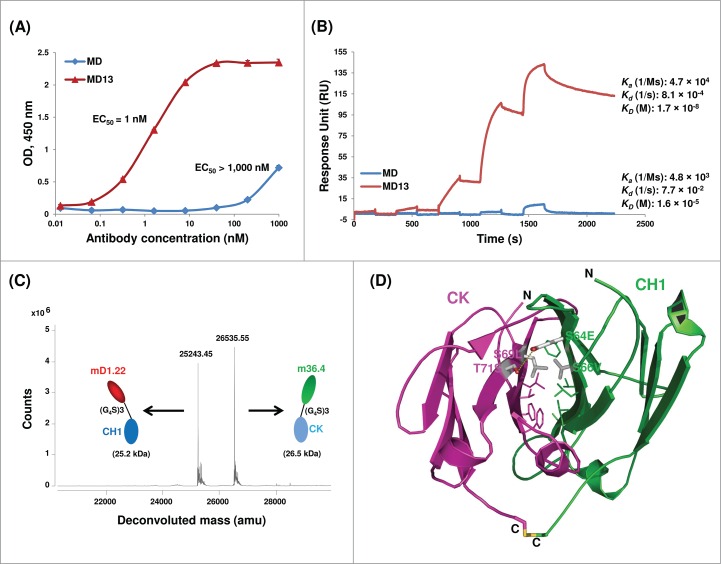

Screening the final library led to the identification of six dominant MD mutants (Fig. 2C). They all have hydrophobic residues in position 66 of CH1 and position 69 of CK (except MD35). In contrast, there is no preferential use of types of amino acid residues in the other two positions. MD12 and MD27 were poorly expressed as soluble proteins in E. coli, and therefore were not further characterized. The other four MD mutants all contained a larger portion of proteins than the wild type that eluted at an aMW comparable to the cMW (52 kDa) of an mD1.22-CH1/m36.4-CK heterodimer, as demonstrated by size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 3). However, only the two chains in MD13 were not dissociated in the presence of 1 mM TCEP. In the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Fig. 4A) and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (Fig. 4B), MD13 showed nanomolar affinities for the HIV-1 Env gp14089.6, ∼1,000-fold higher than those of MD. Other MD mutants also showed ELISA binding activity (EC50s, 1.5-2 nM) much higher than that (EC50, >1,000 nM) of MD although slightly lower than that (EC50, 1 nM) of MD13 likely due to relatively inefficient CH1-CK heterodimerization in the other MD mutants compared to MD13 (data not shown). Given that mD1.22 has nanomolar affinities for the Env, while m36.4 barely binds without sCD4, as demonstrated in our previous studies,4,10,16 the results suggest that the purified MD13 protein should contain mD1.22-CH1. As expected, mass spectrometry confirmed the presence of mD1.22-CH1 with abundance comparable to that of m36.4-CK (Fig. 4C). Structural modeling indicated that the S66V mutation of CH1 and the S69L mutation of CK in MD13 could create hydrophobic packing interactions in between or with other hydrophobic residues at the interface and a hydrogen bond could form between the other two substitutions (S64E of CH1 and T71S of CK) (Fig. 4D).

Figure 3.

Size-exclusion chromatography of MD variants. Proteins were treated with or without 1 mM TCEP before analysis. The arrows at the top indicate the elution volumes of the molecular mass standards in PBS (pH7.4): carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), ovalbumin (44 kDa), and conalbumin (75 kDa).

Figure 4.

Characterization of MD13. (A) ELISA binding to the HIV-1 Env gp14089.6. Gp14089.6 was coated on 96-well plates at a concentration of 2 µg mL−1. Bound MD and MD13 were detected by HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Fab-specific) antibody. (B) Binding kinetics of MD and MD13 with gp14089.6 as measured by SPR. SPR analysis was performed on Biacore X100 by using a single-cycle approach according to the manufacturer's instructions. Analytes were tested at 1,000, 100, 10, 1, and 0.1 nM concentrations. Kinetic constants shown on the right were calculated from the sensorgrams fitted with bivalent binding model of the BiacoreX100 evaluation software 2.0. ka, association rate constant; kd, dissociation rate constant; KD, equilibrium dissociation constant. (C) High-resolution mass spectrometry. Mass spectra were shown with deconvoluted mass for each peak indicated at the top. (D) Structural modeling of the CH1-CK interface in MD13. The side chains of hydrophobic residues at the interface are shown in slim stick representation. The four amino acid substitutions are indicated with their side chains shown in bold stick representation. The yellow dashed line indicates possible formation of a hydrogen bond between the residues. N and C denote the N and C terminus, respectively, of CH1 and CK.

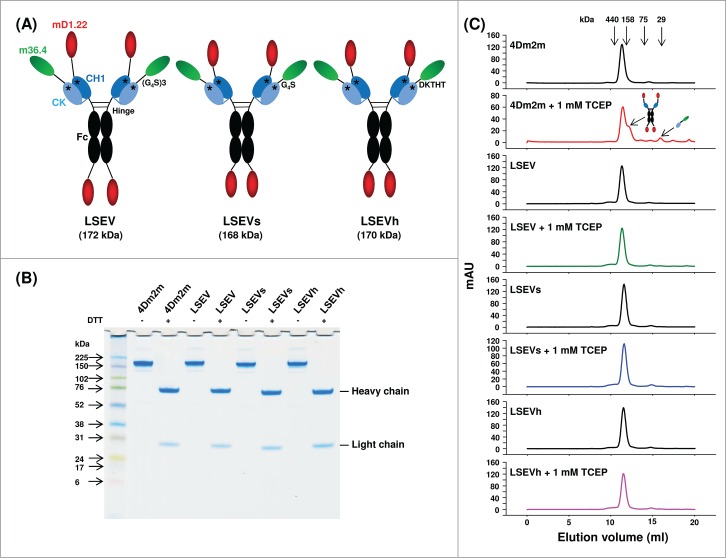

Design, generation and initial characterization of 4Dm2m variants with stabilized CH1-CK and shortened polypeptide linkers

The stabilizing mutations in the CH1-CK of MD13 were introduced into 4Dm2m, resulting in the first variant, LSEV (Fig. 5A). We further hypothesized that shortening the (G4S)3 linkers used in 4Dm2m or replacing them with human sequences naturally designed for both flexibility and stability might render the fusion protein less susceptible to proteolysis. To test this hypothesis, we generated two LSEV variants, one (LSEVs) with a single copy of the G4S motif and the other (LSEVh) with a sequence (DKTHT) derived from the human IgG1 hinge as linkers (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Design, generation and initial characterization of 4Dm2m variants. (A) Schematic representation of 4Dm2m variants. The blue line connecting the C termini of CH1 and CK denotes the inter-chain disulfide bridge. The stars represent the S64E/S66V substitutions in CH1 and S69L/T71S substitutions in CK. Calculated molecular masses are shown in parentheses. (B) Non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE of 4Dm2m variants. Molecular masses of standards are shown on the left. (C) Size-exclusion chromatography of 4Dm2m variants. The arrows at the top indicate the elution volumes of the molecular mass standards in PBS (pH7.4): carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), conalbumin (75 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and ferritin (440 kDa). The arrows in the “4Dm2m + 1 mM TCEP” panel indicate the elution of heavy and light chains of 4Dm2m devoid of each other.

The new 4Dm2m variants were well expressed in transiently transfected 293 free style (293FS) cells and secreted into the culture supernatants. Interestingly, the engineering gradually increased the expression levels of the variants with LSEVh having the highest yield (10-15 mg liter−1), which is ∼2-3-fold higher than that (5-6 mg liter−1) of 4Dm2m, and comparable to that (10–20 mg liter−1) of typical human IgG1s generated in our lab. Unlike the bacterially expressed MD protein (Fig. 1B), 4Dm2m migrated almost as a single band with aMW (∼180 kDa) comparable to its cMW (172 kDa) on an SDS-PAGE under non-reducing condition (Fig. 5B), suggesting that CH1-CK heterodimerization is much more efficient in the mammalian expression system likely due to more efficient protein folding machinery or more favorable cellular environment. As expected, incubation with 1 mM TCEP led to partial dissociation between the heavy and light chains of 4Dm2m while all the variants with stabilized CH1-CK maintained integrity, as demonstrated by size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 5C).

Preserved biological activities and drug-related properties of 4Dm2m variants

To find out whether the engineering would affect biological activities and drug-related properties, we tested the 4Dm2m variants for their ability to neutralize HIV-1 and aggregation propensities during prolonged incubation. CD4-Ig and the recently reported enhanced CD4-Ig (eCD4-Ig, the eCD4-IgQ40A,mim2 variant) 6 were included for comparison. eCD4-Ig is a sCD4-Fc fusion protein with a CCR5-mimicking sulfopeptide fused to the C terminus of Fc. Efficient tyrosine sulfation of the peptide is required for potent HIV-1 neutralization, so eCD4-Ig was produced by co-transfection of 293T cells with a plasmid encoding the human tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase 2 (TPST2) to promote addition of the sulfate moiety onto tyrosine residues.6 We produced eCD4-Ig as described6 (the modified protein designated eCD4-Ig-TPST2) and compared the 4Dm2m variants to both eCD4-Ig-TPST2 and the unmodified eCD4-Ig. eCD4-Ig had similar yield with CD4-Ig and 4Dm2m, while co-transfection of 293FS cells with CD4-Ig- and the human TPST2-encoding plasmids resulted in a drastic decrease (by up to 10-fold) of eCD4-Ig-TPST2 expression.

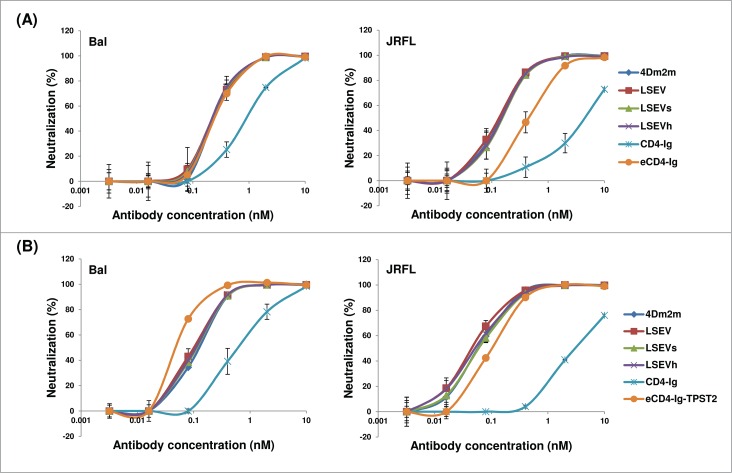

In a neutralization assay with two clade-B R5-tropic HIV-1 primary isolates (Bal and JRFL), we found that none of the engineering approaches apparently diminished the neutralizing activity of 4Dm2m (Fig. 6). While the 4Dm2m variants (IC50, 0.24–0.28 nM) and eCD4-Ig (IC50, 0.28 nM) were equally potent against the tier-1 isolate Bal, the former (IC50, 0.14 nM) neutralized the tier-2 isolate JRFL 3-fold better than the latter (IC50, 0.41 nM) (Fig. 6A). As expected, eCD4-Ig-TPST2 showed increased potency compared to eCD4-Ig and the 4Dm2m variants when Bal was tested; however, eCD4-Ig-TPST2 was still less potent than the 4Dm2m variants in neutralizing JRFL (Fig. 6B). As previously reported,4,6 4Dm2m and eCD4-Ig-TPST2 neutralized both isolates much more efficiently than CD4-Ig.

Figure 6.

HIV-1 neutralizing activity of 4Dm2m variants compared with eCD4-Ig (A) and eCD4-Ig-TPST2 (B). Bal and JRFL are two R5-tropic HIV-1 primary isolates from clade B. Viruses pseudotyped with HIV-1 Envs were produced in 293T cells and the assay was performed in duplicate with HOS-CD4-CCR5 cells as target cells.

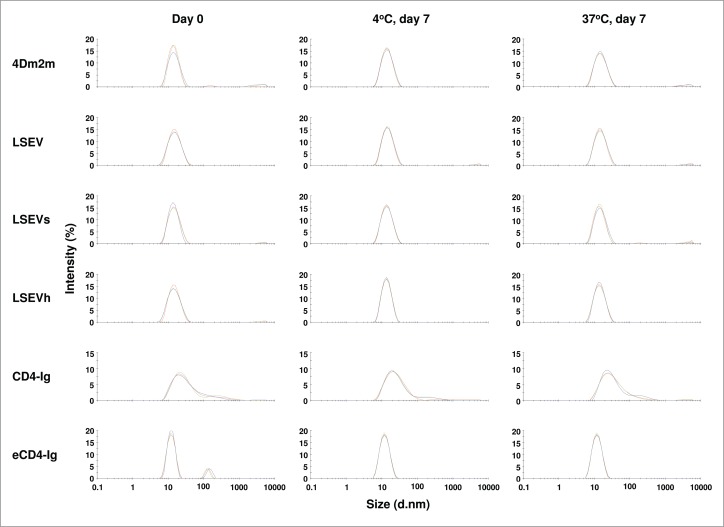

The aggregation propensities of the proteins were evaluated by dynamic light scattering (DLS). Because eCD4-Ig-TPST2 had very low yield and precipitated easily, we used eCD4-Ig in the DLS analysis and in the following animal study for pharmacokinetics. eCD4-Ig also began to precipitate when it was concentrated to 1 mg mL−1 and above. Therefore, eCD4-Ig was tested at a concentration of 1 mg mL−1 while the 4Dm2m variants were analyzed at 5 mg mL−1 in PBS (pH7.4). All proteins were stored at −80°C and slowly thawed on ice before measurement. Our results showed that after the freeze-thaw cycle, large precipitates were observed with eCD4-Ig and the supernatant recovered from high-speed centrifugation contained large particles (diameters, 100-200 nm) at about 10% of total particles (Fig. 7). In contrast, all other protein solutions remained clear and no precipitates were observed after the treatment. The particles of 4Dm2m variants were predominantly small (diameters, 13-15 nm), while a small percentage of the CD4-Ig particles were large, in agreement with our previous study.4 After incubation at 37°C for one and three days, eCD4-Ig still precipitated but large soluble particles were not observed by DLS after the precipitates were removed; the protein was not prone to aggregate at 4°C (data not shown). All other samples appeared to be stable throughout 7 days of incubation at both 4 and 37°C (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Aggregation propensities of 4Dm2m variants. Proteins at a concentration of 1 (for eCD4-Ig) or 5 mg mL−1 (for all other proteins) in PBS (pH7.4) were analyzed via DLS after incubation at either 4 or 37°C for 7 days. Only results from day 0 and 7 are shown. The three curves in each histogram that almost overlap with each other represent three individual measurements.

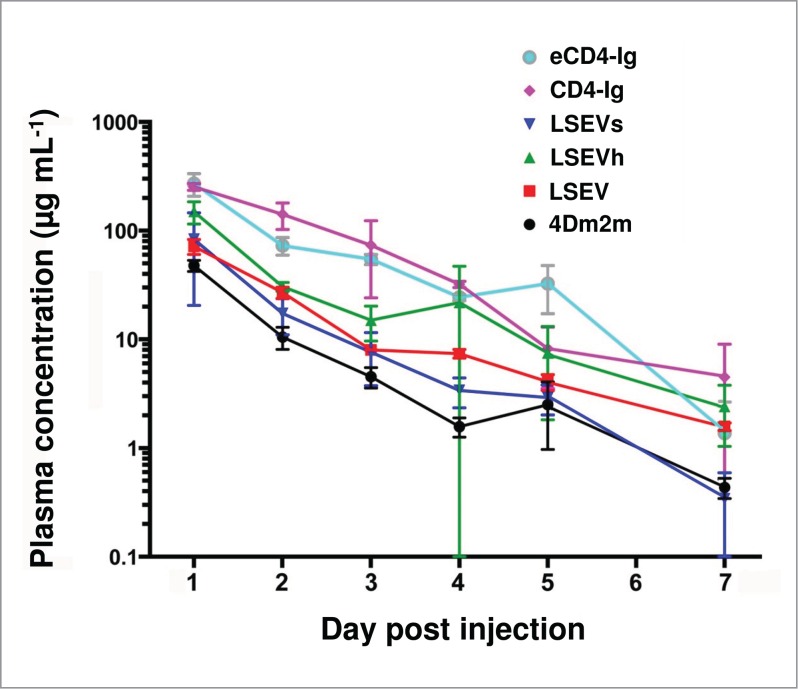

Improved pharmacokinetics of 4Dm2m variants

The pharmacokinetics of the 4Dm2m variants and the control proteins eCD4-Ig and CD4-Ig were tested in C57BL/6 mice. Each mouse was injected intravenously with either 0.1 (for eCD4-Ig) or 1 mg (for all others) proteins and blood samples were collected daily (except on day 6) for 7 days. As expected, the new 4Dm2m variants had higher serum concentrations than 4Dm2m at almost all time points with LSEVh showing the slowest clearance (Fig. 8). The level of CD4-Ig declined at a lower rate than that of LSEVh within the first three days, but CD4-Ig clearance was accelerated thereafter; in contrast, the serum concentrations of LSEVh reached a relatively steady state between day 3-5. Overall and statistically (P = 0.32, Student t test), CD4-Ig did not appear to have more favorable pharmacokinetics than LSEVh. eCD4-Ig showed a similar level of retention with CD4-Ig.

Figure 8.

Pharmacokinetics of 4Dm2m variants in C57BL/6 mice. Animals were intravenously injected with either 0.1 (for eCD4-Ig) or 1 mg (for all others) proteins on day 0. Plasma was collected by submandibular bleeding daily thereafter and serum concentrations of proteins were measured by ELISA. Each group included two animals. Plotted data are means ± standard deviations. The data for eCD4-Ig are dose-normalized.

Further improving the pharmacokinetics of LSEVh by engineering Fc to enhance FcRn binding

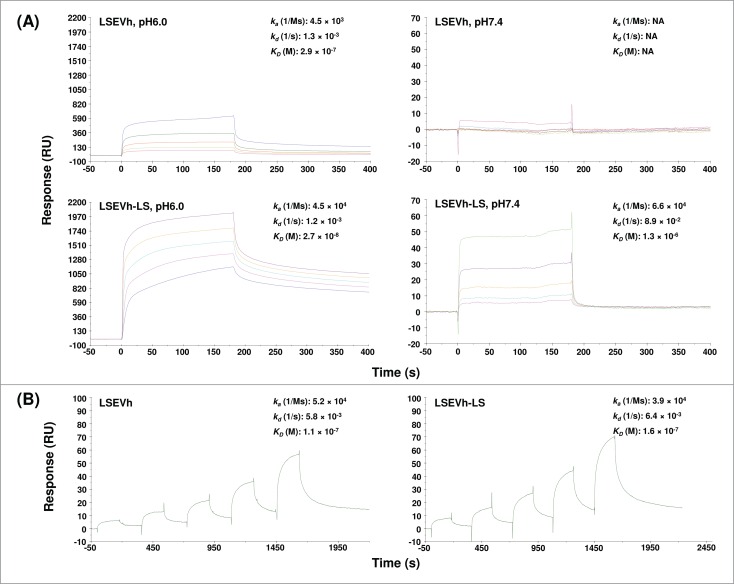

To further improve the pharmacokinetics of LSEVh, we introduced the M428L/N434S double mutations into Fc, which have been found to markedly increase antibody binding to FcRn and half-lives in vivo.17,18 SPR analysis revealed that at pH6.0, LSEVh bound to a recombinant human FcRn with an affinity of 290 nM while no binding was detected at pH7.4 (Fig. 9A). The LSEVh mutant (LSEVh-LS) with the M428L/N434S mutations also exhibited pH-dependent interaction with FcRn and showed an affinity (27 nM) about 11-fold higher than that of LSEVh at pH6.0. In agreement with a previous study,17 the mutagenesis did not affect binding to Fc gamma receptor IIIa (FcγRIIIa) (Fig. 9B), which mediates antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), and HIV-1 neutralization (data not shown).

Figure 9.

Binding kinetics of LSEVh and LSEVh-LS with human FcRn (A) and FcγRIIIa (B) as measured by SPR. SPR analysis was performed on Biacore X100 by using a multi-cycle (for FcRn) or single-cycle (for FcγRIIIa) approach according to the manufacturer's instructions. Analytes were tested at 2,400, 1,200, 600, 300, and 150 nM concentrations. Kinetic constants shown on the right were calculated from the sensorgrams fitted with bivalent (for FcRn) or monovalent (for FcγRIIIa) binding model of the BiacoreX100 evaluation software 2.0. ka, association rate constant; kd, dissociation rate constant; KD, equilibrium dissociation constant.

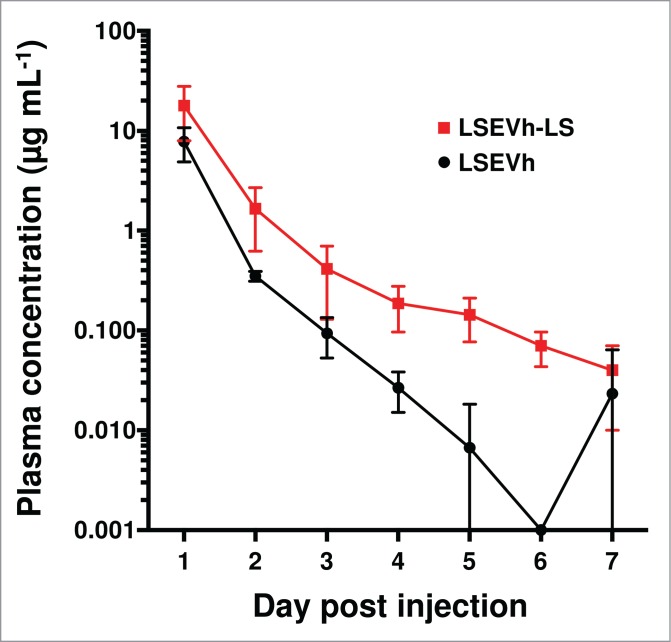

The pharmacokinetics of LSEVh-LS was evaluated in human FcRn transgenic mice as described.17 LSEVh-LS showed several-fold higher serum concentrations than LSEVh at almost all time points (Fig. 10). Interestingly, LSEVh appeared to be cleared much more rapidly in the FcRn transgenic mice than in the C57BL/6 mice (Figs. 8-10). This observation is in agreement with previous reports that mouse FcRn binds IgG from different species with high affinities, while human FcRn is more stringent in its binding specificity.19,20

Figure 10.

Pharmacokinetics of LSEVh and LSEVh-LS in human FcRn transgenic mice. Animals were intravenously injected with 1 mg proteins on day 0. Plasma was collected by submandibular bleeding daily thereafter and serum concentrations of proteins were measured by ELISA. Each group included three animals. Plotted data are means ± standard deviations.

Discussion

Antibody pharmacokinetics is partially determined by properties, which include but are not limited to molecular size, stability, specificity, susceptibility to proteolysis and FcRn binding activity.21,22 This study aimed to improve some properties of the unique fusion protein against HIV-1, 4Dm2m, and evaluate their effects on 4Dm2m pharmacokinetics in mouse models.

Our first finding is that the CH1-CK-mediated heterodimerization of mD1.22 and m36.4 can be markedly enhanced by mutagenesis of the CH1-CK interface. CH1-CK had been previously used as a heterodimerization scaffold to generate bispecific antibodies targeting cytotoxic T or natural killer cells to tumor cells.12,13 However, even after two-step affinity purification against both the CH1 and CK chains, the final products were still a mixture of heterodimers and undesired monomers composed of dissociated CH1 or CK chain. In this study, we found that the purified MD protein was composed of only m36.4-CK monomer and homodimer after single-step purification using an anti-CK ligand (Fig. 1). These results suggest that in bacteria, the CH1-CK interaction is not sufficiently strong to ensure formation of stable heterodimers. Another previous study demonstrated that the use of Fab, but not CH1-CK, as a dimerization scaffold led to efficient production of bispecific and trispecific antibodies.11 This prompted us to engineer CH1-CK to compensate for the loss of heterodimerization strength contributed by VH-VL. By combining structure-guided design and library selection technologies, we identified six CH1-CK mutants that resulted in formation of more stable heterodimers of the MD variants than the wild-type MD (Figs. 2–4). They preferentially used hydrophobic amino acid residues in position 66 of CH1 and position 69 of CK, suggesting that increased hydrophobic interactions were a mechanism for the enhanced heterodimerization. The heterodimerization in MD13 was not affected by 1 mM TCEP (Fig. 3), suggesting strong interactions between CH1 and CK in the absence of the inter-chain disulfide bridge. These stabilized CH1-CK mutants are potentially useful as new scaffolds for generation of bispecific and multispecific antibodies or proteins.

The long (G4S)3 linkers used in 4Dm2m may have rendered the fusion protein more susceptible to proteolytic degradation. A previous study demonstrated that truncation or removal of polypeptide linkers increased the stability of proteins against proteolysis and did not affect their biological activities.23 The human IgG1 hinge is naturally designed for both flexibility and stability. We therefore tested whether shortening the (G4S)3 linkers or replacing them with part of the human IgG1 hinge sequence, when combined with CH1-CK stabilization, could have an effect on the biological and biophysical properties of 4Dm2m in vitro and its pharmacokinetics in vivo. Our results showed that the new 4Dm2m variants retained not only potent HIV-1 neutralizing activity (Fig. 6), but also excellent drug-related properties (Fig. 7). Importantly, LSEV, which bears the CH1-CK stabilizing mutations only, had higher serum concentrations in the C57BL/6 mice at all time points compared to 4Dm2m (Fig. 8). Interestingly, shortening the (G4S)3 linkers to a single copy of the G4S motif in LSEVs did not have additional effects, while replacing the linkers with the IgG1 hinge sequence DKTHT resulted in a further increase of serum concentrations of LSEVh. These results provide supporting evidence for the high stability and flexibility of the human IgG1 hinge and suggest that truncation of the (G4S)3 linkers might not increase resistance to proteolysis. We did not completely remove the linkers, assuming that a certain level of flexibility could be critically important for mD1.22 and m36.4 to exert their functions in a cooperative way.

FcRn plays a critical role in recycling of antibodies by protecting them from degradation in lysosome following endocytosis.24 Engineering the antibody Fc through mutagenesis can increase its binding to FcRn and prolong antibody half-lives in vivo.18, 25-27 Among several sets of amino acid substitutions in Fc reported so far, M428L/N434S are unique in that they do not significantly reduce antibody binding to FcγRIIIa, which mediates ADCC, while increasing FcRn binding by ∼10-fold.17,18 Previous studies have demonstrated that Fc-mediated effector functions of bnAbs, particularly ADCC, contribute substantially to their ability to control HIV-1 infection in vivo.7,8 We therefore introduced the M428L/N434S mutations into LSEVh. Our results showed that LSEVh-LS had higher affinity for FcRn (Fig. 9A) and serum concentrations in human FcRn transgenic mice (Fig. 10) than LSEVh, while their binding to FcγRIIIa was comparable (Fig. 9B), in agreement with previous studies.17,18

In summary, we successfully improved the pharmacokinetics of 4Dm2m in mice by combining three different approaches. The pharmacokinetic profile still might not be ideal if the protein is to be used for prevention or sustained therapy of HIV-1 infection. However, when combined with antiretroviral therapy and reagents that activate latently infected cells toward the final goal of HIV-1 eradication, the relatively short half-life may not be of substantial concern. The engineering might lead to immunogenicity, but this possibility can only be definitely evaluated by human clinical trials.

Materials and methods

Cells, viruses, plasmids, proteins and other reagents

We purchased the 293T cells (ATCC, CRL-3216), the 293FS cells (ThermoFisher Scientific, R790-07), the plasmid encoding human TPST2 (OriGene, RC204969), recombinant human FcγRIIIa (R&D Systems, 4325-Fc-050), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Fc-specific) antibody (Sigma, A0170), HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Fab-specific) antibody (Sigma, A0293) and TCEP (Sigma, C4706). Other cell lines and plasmids used for production of pseudotyped HIV-1 and neutralization assays were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. Gp14089.6 was a gift from Barton F. Haynes (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC). Gp140SC,9 CD4-Ig,4,9 and soluble human FcRn28 were produced in our laboratory.

Computational analysis for identification of amino acid residues at the CH1-CK interface for mutagenesis

The atomic coordinates of CH1-CK were extracted from the crystal structure of the HIV-1 bnAb b12 (Protein Data Bank entry 1HZH). All hydrophobic residues at the CH1-CK interface were represented by using the PyMOL molecular graphics system (version 1.5.0.4; Schrödinger, LLC). Void structures at the CH1-CK interface were located by concomitantly visualizing the side chains of the amino acid residues at the interface. Single point mutations were modeled using the PyMOL mutagenesis wizard with an appropriate side-chain rotamer.

Cloning of MD

The following primers were used: MLF, 5′-ACCGTGGCCCAGGCGGCCCAGGTGCAGCTGGTGCAG-3′ (sense);

MLR, 5′-CTAATTAATTATCTAGAATTACTCGAGTTTAGCTGCCGGTGCGGGTGTAGCTGCAGGACACTCTCCCCTGTTGAA-3′ (antisense); DHF, 5′-CAACCAGCCATGGCCAAGAAGGTGGTGTACGGC-3′ (sense);

DHR, 5′-TGGAGGCCGGCCTGGCCTTACTCGAGTTTAGCTGCCGGTGCGGGTGTAGCTGCAGGACAAGATTTGGGCTCAACTTTCTTGTCCACCTT-3′ (antisense); HeavyF, 5′-GCCTACGGCAGCCGCTGGATTGTTATTACTTGCTGCCCAACCAGCCATGGC-3′ (sense); LightR, 5′-CCAGCGGC TGCCGTAGGCAATAGGTATTTCATTTTAAATTCCTCCT AATTAATTATCTAG-3′ (antisense).

The mD1.22-CH1 and m36.4-CK gene fragments were PCR amplified with the 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid as a template and the primer pairs DHF/DHR and MLF/MLR, respectively. Extension of the gene fragments was then performed with primer pairs HeavyF/DHR and MLF/LightR, respectively, to add the pelB signal sequence. To obtain the full-length MD gene fragment, m36.4-CK was joined to mD1.22-CH1 by overlapping PCR with both templates in the same molarities for 7 cycles in the absence of primers and 15 additional cycles in the presence of primers MHF and DHR. The PCR product appended with SfiI restriction site on both sides was digested and cloned into pComb3X.

Construction, panning and screening of a phage-display library of MD mutants

The phage-display library of MD mutants was constructed by site-directed random mutagenesis. We used the following primers: Bomp, 5′-GTGTGGAATTGTGAGCGG-3′ (sense); STR, 5′-GAGGCTGTAGGTGCTGTC-3′ (antisense); STF, 5′-GACAGCACCTACAGCCTCNNSAGCNNSCTGACGCTGAGCAAAGC-3′ (sense); SSR, 5′-GTAGAGTCCTGAGGACTG-3′ (antisense); SSF, 5′-CAGTCCTCAGGACTCTACNNSCTCNNSAGCGTGGTGACCGTGCCC-3′ (sense); mDOR, 5′-TGGTGGCCGGCCTGGCCACAAGATTTGGGCTCAAC-3′ (antisense).

To randomize the S69 and T71 residues of CK, a gene fragment containing the C-terminal sequence of CK, pelB signal sequence, mD1.22 and the N-terminal sequence of CH1 was amplified by PCR with MD-encoding plasmid as a template and primers STF and SSR. To mutate the S64 and S66 residues of CH1, the C-terminal sequence of CH1 was PCR amplified with primers SSF and mDoR. The two PCR products were joined together by overlapping PCR with both templates in the same molarities for 7 cycles in the absence of primers and 15 additional cycles in the presence of primers STF and mDoR. For assembly of the full-length fragments of MD mutants, a gene fragment containing m36.4 and the N-terminal sequence of CK was PCR amplified with the primers Bomp and STR, and then linked to the fragment having all the mutations in CH1 and CK by overlapping PCR with the primers Bomp and mDoR. The final product was digested with SfiI and cloned into the phagemid pComb3X. A phage library was prepared by electroporation of E. coli strain TG1 electroporation-competent cells (Lucigen) with desalted and concentrated ligation, as described previously.29

To select MD mutants with preserved binding to HIV-1 Env and increased CH1-CK heterodimerization, we cycled the library through three rounds of panning against gp140SC followed by two additional rounds of panning against TCEP. Panning with gp140SC was performed according to the previously described protocols,30 except that in this study we used 1, 0.1 and 0.1 µg of the antigen in the first, second and third rounds of panning, respectively.

For panning with TCEP, the phage library generated from the third round of panning with gp140SC was incubated with 1 mM TCEP at room temperature for 1 h. TCEP and the m36.4-CK chain dissociated from the mD1.22-CH1 chain, which was fused to the filamentous phage coat protein III, were removed by passing the phage library through the Millipore 4-mL centrifugal filter with a cut-off of 100 kDa. The library was dialyzed against 4 mL PBS (pH7.4) three times and then passed through the GE Healthcare HiTrap KappaSelect resin. The resin was washed with 10 mL PBS (pH7.4) twice. Bound phage was eluted by 0.1 mM acetic acid buffer (pH3.0) and neutralized by 1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH9.0) at a volume 1/10 that of elution buffer. Recovered phage was used to prepare a new library for the second round of panning, which was performed in the same way except for the use of 10 mM TCEP for selection. To identify individual mutants that preserved binding to the Env and survived the incubation with TCEP, clones were randomly picked from the last round of panning, inoculated into 96-well plates, and induced for protein expression with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. After overnight incubation, the supernatants of individual clones were screened for binding to gp140SC by using soluble expression-based monoclonal ELISA (semELISA) as described previously.31

Cloning of 4Dm2m variants with stabilizing mutations in CH1 and CK, shortened linkers and enhanced binding to FcRn

The following primers were used: bnIgG20L1, 5′-GTGTAAGCTTACCATGGGTGTGCCCACTCAGGTCCTGGGGTTGCTG-3′ (sense); LSR, 5′-GAGGCTGTAGGTGCTGTC-3′ (antisense); LSF, 5′-AGCACCTACAGCCTCCTGAGCTCGCTGACGCTGAGCAAAGC-3′ (sense); CKR3, 5′-CAATGAATTCATTAACACTCTCCCCTG-3′ (antisense); SacF, 5′-GATCGAGCTCAGCTTCCACC-3′ (sense); EVR, 5′-CACGGTCACCACGCTCACGAGCTCGTAGAGTCCTGAGGACTG-3′ (antisense); EVF, 5′-AGCGTGGTGACCGTGCCC-3′ (sense); AAAR, 5′-CCCGAGGTCGACGCTCTC-3′ (antisense); G4SR1, 5′-TGACCCGCCTCCACCTGAGGAGACGGTGACCAG-3′ (antisense); G4SF2, 5′-GGTGGAGGCGGGTCACGAACTGTGGCTGCACCA-3′ (sense); bnIgG20H1, 5′-GTGTTCTAGAGCCGCCACCATGGAATGGAGCTGGGTCTTTCTCTTC-3′ (sense); mD1.22R21, 5′-GCT GAGCTCCCGCCTCCACCGCCTACCACTACCAGC TG-3′; CH3R5, 5′-TGACCCGCCTCCACCTTTACCCGGAGACAGGGA-3′ (antisense); mD1.22F16, 5′-GGTGGAGGCGGGTCAAAGAAGGTGGTGTACGGC-3′ (sense); DKR1, 5′-TGTGTGAGTTTTGTCTGAGGAGACGGTGACCAG-3′ (antisense); DKF1, 5′-GACAAAACTCACACACGAACTGTGGCTGCACCA-3′ (sense); mD1.22R22, 5′-GCTGAGCTCGTGTGAGTTTTGTCGCCTACCACTACCAGCTG-3′ (antisense); CH3R6, 5′-GGTATGCGTCTTATCTTTACCCGGAGACAGGGA-3′ (antisense); mD1.22F17, 5′-GATAAGACGCATACCAAGAAGGTGGTGTACGGC-3′ (sense); FcF6, 5′-GACAAAACTCACACATGC-3′ (sense); LSR1, 5′-CTTCTGCGTGTAGTGGCTGTGCAGAGCCTCATGCAGCACGGAGCATGAGAAG-3′ (antisense); LSF1, 5′-CTTCTCATGCTCCGTGCTGCATGAGGCTCTGCACAGCCACTACACGCAGAAG-3′ (sense); FcR8, 5′-TTTACCCGGAGACAGGGAG-3′ (antisense); CH1R4, 5′-TGTGTGAGTTTTGTCACAAGATTTGGGCTCAACTTTCT TGTCCACCTTG-3′ (antisense); DAF, 5′-CTCCCTGTCTCCGGGTAAA-3′ (sense).

For cloning of LSEV, we first introduced the S69L and T71S mutations into CK with pDR12 vector-based 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid4 as a template. A gene fragment encoding the light chain leader peptide (Lleader), m36.4 and the N-terminal sequence of CK was PCR amplified with 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid as a template and primers bnIgG20L1 and LSR. The C-terminal portion of CK was amplified with primers LSF and CKR3. The two gene fragments were fused to each other by overlapping PCR with primers bnIgG20L1 and CKR3. The product was digested with HindIII and EcoRI, and cloned into the 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid linearized by the same restriction enzymes. To introduce the S64E and S66V mutations into CH1, the N-terminal sequence of CH1 was PCR amplified with 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid as a template and primers SacF and EVR. A long fragment containing the C-terminal portion of CH1, Fc, mD1.22 and polyA signal sequence was amplified with 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid as a template and primers EVF and AAAR. The two fragments were linked to each other by overlapping PCR with primers SacF and AAAR. The product was digested with SacI and SalI, and cloned into the construct containing the S69L and T71S mutations in CK.

To clone LSEVs, we first generated a 4Dm2m variant (designated 4Dm2ms) containing only the G4S linker as an intermediate construct. To shorten the linker between m36.4 and CK in the light chain, the Lleader-m36.4 and CK gene fragments were PCR amplified with 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid as a template and primer pairs bnIgG20L1/G4SR1 and G4SF2/CKR3, respectively. They were linked together by overlapping PCR with primers bnIgG20L1 and CKR3. The product was digested with HindIII and EcoRI, and cloned into the 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid linearized by the same restriction enzymes. To shorten the linker between mD1.22 and CH1 in the heavy chain, a gene fragment containing the heavy chain leader peptide (Hleader) and mD1.22 was PCR amplified with 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid as a template and primers bnIgG20H1 and mD1.22R21. The product was digested with XbaI and SacI, and cloned into the construct with shortened G4S linker in the light chain. To shorten the linker between Fc and mD1.22 at its C terminus, the two gene fragments encoding the heavy chain constant region and mD1.22-polyA signal sequence were amplified with 4Dm2m-encoding plasmid as a template and primer pairs SacF/CH3R5 and mD1.22F16/AAAR, respectively. They were fused to each other by overlapping PCR with primers SacF and AAAR. The product was digested with SacI and SalI, and cloned into the previous construct containing shortened G4S linkers in the light chain and between mD1.22 and CH1 in the heavy chain. The 4Dm2ms-encoding plasmid was then used as a template to generate LSEVs by using the same protocols for cloning LSEV.

LSEVh was constructed in the same way as LSEVs was generated. The primer pairs bnIgG20L1/DKR1 and DKF1/CKR3 were used to PCR amplify the Lleader-m36.4 and CK gene fragments, respectively, to replace the (G4S)3 linker between m36.4 and CK with DKTHT. The primers bnIgG20H1 and mD1.22R22 were used to amplify the Hleader-mD1.22 gene fragment to replace the (G4S)3 linker between mD1.22 and CH1 with DKTHT. The primer pairs SacF/CH3R6 and mD1.22F17/AAAR were used to amplify the gene fragments encoding the heavy chain constant region and mD1.22-polyA signal, respectively, to replace the (G4S)3 linker between Fc and mD1.22 at its C terminus with DKTHT.

To generate LSEVh-LS, the N- and C-terminal sequences of Fc were PCR amplified with an Fc-encoding plasmid as a template and primer pairs FcF6/LSR1 and LSF1/FcR8, respectively. Full-length Fc gene fragment bearing the two mutations was obtained by overlapping PCR with primers FcF6 and FcR8. The CH1 and mD1.22-polyA signal sequences were PCR amplified with primer pairs SacF/CH1R4 and DAF/AAAR, respectively, and fused to the N and C terminus, respectively, of Fc by overlapping PCR with primers SacF and AAAR. The product was digested with SacI and SalI, and cloned into the LSEVh-encoding plasmid linearized by the same restriction enzymes.

Cloning of eCD4-Ig

The following primers were used: D1D2F1, 5′-ACGCGGCCCAGCCGGCCAAGAAGGTGGTGCTGGGC-3′ (sense); D1D2R1, 5′-GGTCAGGAAGCTGCCCGCGTTGCCCAGGATCTTG-3′ (antisense); D1D2F2, 5′-GGCAGCTTCCTGACCAAG-3′ (sense); D1D2R2, 5′-TGTGTGAGTTTTGT CACAAGATTTGGGCTCCGGGTCTGCCGCGGCCAGCACCACGATGTC-3′ (antisense); FcF5, 5′-GACAAAACTCACACATGC-3′ (sense); Min2R, 5′-GCGGGTTTAAACTCAATCCATATCGTAGTAGTAGCCC CCATCGTAGTCGTAGTAGTCTCCACCGCCTCCACCTTTACCCGGAGACAGGGAGAG-3′ (antisense).

eCD4-Ig was cloned according to the sequence reported previously.6 To introduce the Q40A mutation into the human CD4 D1D2 domains, the gene fragments encoding the N- and C-terminal sequence of D1D2 were PCR amplified with D1D2-encoding plasmid as a template and primer pairs D1D2F1/D1D2R1 and D1D2F2/D1D2R2, respectively. They were linked to each other by overlapping PCR with primers D1D2F1 and D1D2R2. The gene fragment containing the human IgG1 Fc and the CCR5 mimetic mim2 at its C terminus was PCR amplified with Fc-encoding plasmid as a template and primers FcF5 and Min2R, and then fused to the D1D2 gene fragment by overlapping PCR with primers D1D2F1 and Min2R. The final product was digested with SfiI and PmeI, and cloned into pSecTagB.

Protein expression and purification

MD variants were expressed in E. coli HB2151 cells and all 4Dm2m variants were expressed in 293FS cells as described previously.16 To boost tyrosine sulfation, 293FS cells were cotransfected with antibody-encoding and TPST2-encoding plasmids at a 1:1 ratio. MD variants were purified from the soluble fraction of E. coli periplasm by using the GE Healthcare HiTrap KappaSelect resin according to the manufacturer's instructions. 4Dm2m variants were purified from the 293FS cell culture supernatants by Protein A Sepharose 4 Fast Flow column chromatography (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Size-exclusion chromatography

A Superdex200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) was calibrated with protein molecular mass standards of carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), ovalbumin (44 kDa), conalbumin (75 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa) and ferritin (440 kDa). Purified proteins at a concentration of 1 mg mL−1 in PBS (pH7.4) were loaded onto the pre-equilibrated column and eluted with PBS (pH7.4) at 0.5 mL/min.

High-resolution mass spectrometry

High-resolution mass spectrometry was performed according to the previously described protocol.32

ELISA

ELISA was performed as described previously.16 Briefly, antigens were coated on 96-well plates at a concentration of 2 µg mL−1. Bound MD variants were detected by HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Fab-specific) antibody. Bound 4Dm2m variants were detected by HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Fc-specific) antibody. Half-maximal binding (EC50) was calculated by fitting data to the Langmuir adsorption isotherm.

SPR

Binding kinetics of MD variants with gp14089.6 were assessed by SPR on Biacore X100 (GE Healthcare) using a single-cycle approach as described previously.9 Analytes were tested at 1,000, 100, 10, 1, and 0.1 nM concentrations. Binding kinetics of 4Dm2m variants with FcRn and FcγRIIIa were assessed by using a multi-cycle and single-cycle approach, respectively, according to the previously described protocols.9,28 Analytes were tested at 2,400, 1,200, 600, 300, and 150 nM concentrations. Kinetic constants were calculated from the sensorgrams fitted with bivalent (for gp14089.6 and FcRn) or monovalent (for FcγRIIIa) binding model of the BiacoreX100 evaluation software 2.0.

Pseudovirus neutralization assay

HIV-1 pseudoviruses were generated and neutralization assays were performed as described previously.16

DLS

Proteins concentrated to 1 mg mL−1 (for eCD4-Ig) or 5 mg mL−1 (for all other samples) were stored at −80°C and slowly thawed on ice before measurement. Samples were then incubated at 4°C or 37°C. On day 0, 1, 3, and 7, samples were collected and centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min to remove precipitates. The supernatants were diluted to 0.5 mg mL−1 and used for DLS measurement (Zetasizer Nano ZS 3600, Malvern Instruments Limited, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Pharmacokinetic measurement in mice

C57BL/6 mice were bred and maintained at the BSL2 animal facility at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Human FcRn transgenic mice mFcRn−/−hFcRn(267)Tg/Tg (stock number 004919) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Animals were intravenously injected with either 0.1 (for eCD4-Ig) or 1 mg (for all others) proteins on day 0. Plasma samples were collected by submandibular bleeding daily for 7 days after injection. Plasma concentrations of proteins were determined by ELISA with standard curves generated using the original protein stocks and the HIV-1 Env gp14089.6.

Study approval

All the studies were performed under protocols approved by the Institute for Animal Studies at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in compliance with the animal experimentation guidelines of the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barton F. Haynes for providing reagents. This project was supported by the Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program (IATAP) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute (NCI), Center for Cancer Research, the US-China Program for Biomedical Research Cooperation, US-China Program for Research Toward a Cure for HIV/AIDS from NIH and National Nature Science Foundation of China (#81361120378 and #81561128006), and the NIH/NIDA grants DA033788 and DA036171.

References

- 1.Caskey M, Klein F, Lorenzi JC, Seaman MS, West AP Jr, Buckley N, Kremer G, Nogueira L, Braunschweig M, Scheid JF, et al.. Viraemia suppressed in HIV-1-infected humans by broadly neutralizing antibody 3BNC117. Nature 2015; 522:487-91; PMID:25855300; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Ying T, Dimitrov DS. Antibody-based candidate therapeutics against HIV-1: implications for virus eradication and vaccine design. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2013; 13:657-71; PMID:23293858; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1517/14712598.2013.761969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein F, Halper-Stromberg A, Horwitz JA, Gruell H, Scheid JF, Bournazos S, Mouquet H, Spatz LA, Diskin R, Abadir A, et al.. HIV therapy by a combination of broadly neutralizing antibodies in humanized mice. Nature 2012; 492:118-22; PMID:23103874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen W, Feng Y, Prabakaran P, Ying T, Wang Y, Sun J, Macedo CD, Zhu Z, He Y, Polonis VR, et al.. Exceptionally potent and broadly cross-reactive, bispecific multivalent HIV-1 inhibitors based on single human CD4 and antibody domains. J Virol 2014; 88:1125-39; PMID:24198429; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.02566-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagenaur LA, Villarroel VA, Bundoc V, Dey B, Berger EA. sCD4-17b bifunctional protein: extremely broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 Env pseudotyped viruses from genetically diverse primary isolates. Retrovirology 2010; 7:11; PMID:20158904; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1742-4690-7-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner MR, Kattenhorn LM, Kondur HR, von Schaewen M, Dorfman T, Chiang JJ, Haworth KG, Decker JM, Alpert MD, Bailey CC, et al.. AAV-expressed eCD4-Ig provides durable protection from multiple SHIV challenges. Nature 2015; 519:87-91; PMID:25707797; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis GK. Role of Fc-mediated antibody function in protective immunity against HIV-1. Immunology 2014; 142:46-57; PMID:24843871; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/imm.12232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bournazos S, Klein F, Pietzsch J, Seaman MS, Nussenzweig MC, Ravetch JV. Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies require Fc effector functions for in vivo activity. Cell 2014; 158:1243-53; PMID:25215485; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, Feng Y, Gong R, Zhu Z, Wang Y, Zhao Q, Dimitrov DS. Engineered single human CD4 domains as potent HIV-1 inhibitors and components of vaccine immunogens. J Virol 2011; 85:9395-405; PMID:21715496; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.05119-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W, Xiao X, Wang Y, Zhu Z, Dimitrov DS. Bifunctional fusion proteins of the human engineered antibody domain m36 with human soluble CD4 are potent inhibitors of diverse HIV-1 isolates. Antiviral Res 2010; 88:107-15; PMID:20709110; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoonjans R, Willems A, Schoonooghe S, Fiers W, Grooten J, Mertens N. Fab chains as an efficient heterodimerization scaffold for the production of recombinant bispecific and trispecific antibody derivatives. J Immunol 2000; 165:7050-7; PMID:11120833; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller KM, Arndt KM, Strittmatter W, Pluckthun A. The first constant domain (C(H)1 and C(L)) of an antibody used as heterodimerization domain for bispecific miniantibodies. FEBS Lett 1998; 422:259-64; PMID:9490020; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00021-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rozan C, Cornillon A, Petiard C, Chartier M, Behar G, Boix C, Kerfelec B, Robert B, Pelegrin A, Chames P, et al.. Single-domain antibody-based and linker-free bispecific antibodies targeting FcgammaRIII induce potent antitumor activity without recruiting regulatory T cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2013; 12:1481-91; PMID:23757164; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allaway GP, Davis-Bruno KL, Beaudry GA, Garcia EB, Wong EL, Ryder AM, Hasel KW, Gauduin MC, Koup RA, McDougal JS, et al.. Expression and characterization of CD4-IgG2, a novel heterotetramer that neutralizes primary HIV type 1 isolates. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1995; 11:533-9; PMID:7576908; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/aid.1995.11.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothlisberger D, Honegger A, Pluckthun A. Domain interactions in the Fab fragment: a comparative evaluation of the single-chain Fv and Fab format engineered with variable domains of different stability. J Mol Biol 2005; 347:773-89; PMID:15769469; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen W, Zhu Z, Feng Y, Dimitrov DS. Human domain antibodies to conserved sterically restricted regions on gp120 as exceptionally potent cross-reactive HIV-1 neutralizers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:17121-6; PMID:18957538; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0805297105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ko SY, Pegu A, Rudicell RS, Yang ZY, Joyce MG, Chen X, Wang K, Bao S, Kraemer TD, Rath T, et al.. Enhanced neonatal Fc receptor function improves protection against primate SHIV infection. Nature 2014; 514:642-5; PMID:25119033; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zalevsky J, Chamberlain AK, Horton HM, Karki S, Leung IW, Sproule TJ, Lazar GA, Roopenian DC, Desjarlais JR. Enhanced antibody half-life improves in vivo activity. Nat Biotechnol 2010; 28:157-9; PMID:20081867; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt.1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ober RJ, Radu CG, Ghetie V, Ward ES. Differences in promiscuity for antibody-FcRn interactions across species: implications for therapeutic antibodies. Int Immunol 2001; 13:1551-9; PMID:11717196; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/intimm/13.12.1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proetzel G, Roopenian DC. Humanized FcRn mouse models for evaluating pharmacokinetics of human IgG antibodies. Methods 2014; 65:148-53; PMID:23867339; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W, Wang EQ, Balthasar JP. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008; 84:548-58; PMID:18784655; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/clpt.2008.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keizer RJ, Huitema AD, Schellens JH, Beijnen JH. Clinical pharmacokinetics of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Clin Pharmacokinet 2010; 49:493-507; PMID:20608753; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2165/11531280-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishi N, Itoh A, Fujiyama A, Yoshida N, Araya S, Hirashima M, Shoji H, Nakamura T. Development of highly stable galectins: truncation of the linker peptide confers protease-resistance on tandem-repeat type galectins. FEBS Lett 2005; 579:2058-64; PMID:15811318; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol 2007; 7:715-25; PMID:17703228; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri2155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dall'Acqua WF, Kiener PA, Wu H. Properties of human IgG1s engineered for enhanced binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). J Biol Chem 2006; 281:23514-24; PMID:16793771; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M604292200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinton PR, Xiong JM, Johlfs MG, Tang MT, Keller S, Tsurushita N. An engineered human IgG1 antibody with longer serum half-life. J Immunol 2006; 176:346-56; PMID:16365427; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petkova SB, Akilesh S, Sproule TJ, Christianson GJ, Al Khabbaz H, Brown AC, Presta LG, Meng YG, Roopenian DC. Enhanced half-life of genetically engineered human IgG1 antibodies in a humanized FcRn mouse model: potential application in humorally mediated autoimmune disease. Int Immunol 2006; 18:1759-69; PMID:17077181; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/intimm/dxl110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng Y, Gong R, Dimitrov DS. Design, expression and characterization of a soluble single-chain functional human neonatal Fc receptor. Protein Expr Purif 2011; 79:66-71; PMID:21453773; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pep.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen W, Zhu Z, Feng Y, Xiao X, Dimitrov DS. Construction of a large phage-displayed human antibody domain library with a scaffold based on a newly identified highly soluble, stable heavy chain variable domain. J Mol Biol 2008; 382:779-89; PMID:18687338; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu Z, Dimitrov AS, Bossart KN, Crameri G, Bishop KA, Choudhry V, Mungall BA, Feng YR, Choudhary A, Zhang MY, et al.. Potent neutralization of Hendra and Nipah viruses by human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 2006; 80:891-9; PMID:16378991; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.80.2.891-899.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen W, Zhu Z, Feng Y, Dimitrov DS. A large human domain antibody library combining heavy and light chain CDR3 diversity. Mol Immunol 2010; 47:912-21; PMID:19883941; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.09.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu Z, Ramakrishnan B, Li J, Wang Y, Feng Y, Prabakaran P, Colantonio S, Dyba MA, Qasba PK, Dimitrov DS. Site-specific antibody-drug conjugation through an engineered glycotransferase and a chemically reactive sugar. MAbs 2014; 6:1190-200; PMID:25517304; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/mabs.29889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]