Abstract

Purpose of review

The purpose of this review is to discuss the options for, and recent developments in, the surgical treatment of corneal infections. While the mainstay of treatment of corneal infections is topical antimicrobial agents, surgical intervention may be necessary in a number of cases. These include advanced disease at presentation, resistant infections, and progressive ulceration despite appropriate treatment. Prompt and appropriate treatment can make the difference between a good outcome and loss of vision or the eye.

Recent findings

There are a number of surgical therapies available for corneal infections. Preferred therapeutic modalities differ based on the size, causation, and location of the infection but consist of either replacement of the infected tissue or structural support of the tissue to allow healing. While there are no completely novel therapies that have been developed recently, there have been incremental improvements in the existing treatment modalities making them more effective, easier, and safer.

Summary

Several options are available for surgically managing corneal infections. Ophthalmologists should select the optimal procedure based on the individual patient’s situation.

Keywords: Corneal infection, therapeutic keratoplasty, corneal gluing, amniotic membrane, conjunctival graft

Introduction

Corneal infections can be caused by a myriad of pathogens including bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses. The initial process, in most cases, is the adherence and penetration of the infectious agent through the corneal epithelium. This results in an inflammatory cascade that produces inflammatory cells and cytokines such as interleukins and matrix metalloproteinases. While these have antimicrobial functions, they also degrade the corneal structural proteins and result in ulceration of the corneal stroma.(1) Progression of this process can result in perforation of the cornea and extension of the infection into the eye with a high probability of loss of vision or the eye.(Figure 1) Therefore, infectious keratitis needs rapid and aggressive treatment to maintain the integrity of the eye.

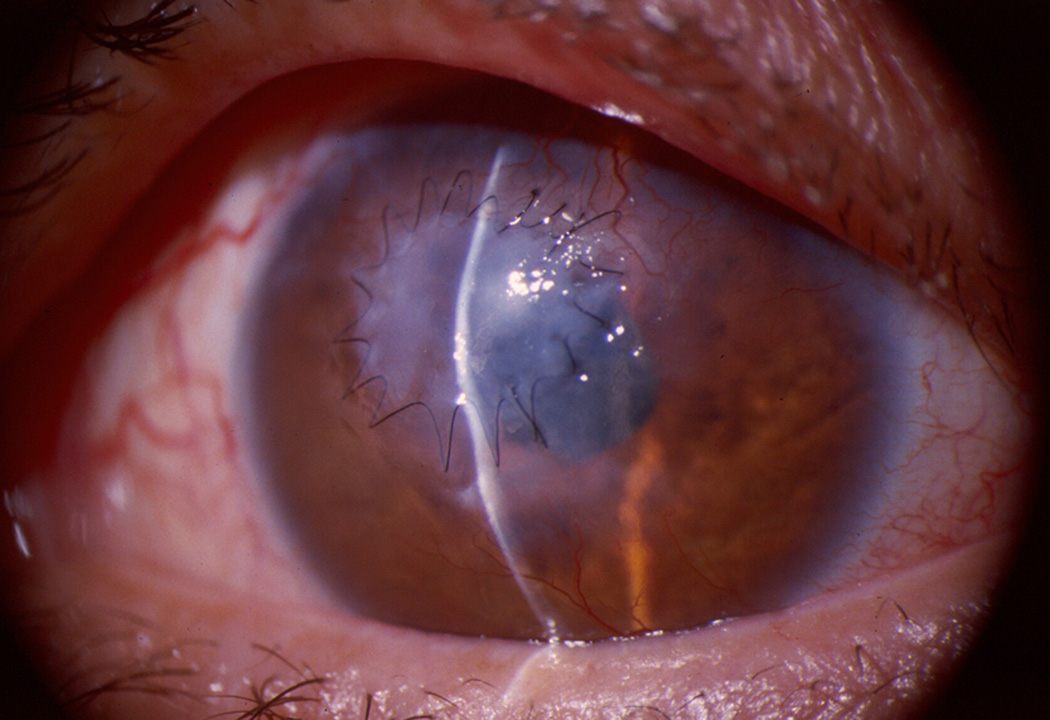

Figure 1.

Severe pseudomonas keratitis with large hypopyon that required a therapeutic penetrating corneal transplantation as it perforated despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy

The mainstay of treatment of infectious keratitis is frequent topical application of antimicrobial agents. Although usually effective in eliminating the infectious agent, the incidence of resistance of infectious agents to antibiotics and antivirals is increasing.(2, 3) In conditions such as fungal and Acanthamoeba infections, topical medications are not very effective and mixed bacterial and fungal infections probably have the worst outcomes of all.(4) Another problem is the fact that antimicrobial agents, and the preservatives in the topical medications, are toxic and can prevent corneal healing.(5) Finally, despite eliminating the infectious agent, the inflammatory cells and cytokines that have been recruited to the eye continue to cause progressive corneal damage. Thus, corneal infections may require surgical management in addition to medical management to either control a resistant infection, or to manage the complications of the infection or its treatment.

Surgical management consists of three basic modalities: (1) methods to maintain structural integrity temporarily to allow the underlying tissue to heal such as corneal gluing; (2) methods to scaffold the tissue breach with tissues that have anti-inflammatory, anti-infectious, or growth factors to enhance healing such as amniotic membrane and conjunctival flaps and; (3) replacement of infected tissue by performing penetrating or lamellar keratoplasty.

Text of Review

Surgical intervention may be needed in up to 30%–40% of infectious keratitis depending on the etiology and severity of infections at presentation.(6) Studies have shown that while bacterial and Acanthamoeba infections can be frequently controlled with medical management, fungal infections may require surgical management in 25–50% of cases.(7, 8) This is becoming even more significant as the relative incidence of bacterial keratitis referred to tertiary institutions appears to be decreasing while that of fungal keratitis appears to be increasing.(9–11) The indications for surgical intervention in corneal infections include worsening or non-responding infection despite treatment with antimicrobials, progressive thinning, descemetocele, and perforation of the cornea. The goal of surgical intervention is to maintain globe integrity and infection resolution; improvement in vision is of secondary concern. The major surgical interventions include corneal gluing, amniotic membrane transplantation, conjunctival grafts, and corneal transplantation.

Corneal gluing

The concept behind glue application is to reestablish corneal and globe integrity in cases of infectious keratitis with significant ulceration resulting in perforations or descemetoceles. This may be a temporary measure to allow time for corneal transplant tissue to be procured and a therapeutic graft to be performed. However, in some cases, especially peripheral ulcers, the glue may be left in place for prolonged periods allowing corneal tissue to heal beneath the adhesive until the glue is passively extruded.(12) In addition to providing structural support, inhibition of inflammation is also achieved. The mechanism for this is believed to be due to the impediment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes thereby preventing their collagenolytic and proteolytic effects on the corneal stromal.(13)

Two primary forms of tissue adhesives have been used – the biologic derivative, fibrin glue, and the synthetic tissue adhesives that are derivatives of cyanoacrylate. Fibrin glue has more frequently been utilized during ocular surgery for wound closures and has little utility in the management of corneal ulcers other than securing amniotic membrane if that treatment modality is used.(14) The synthetic glues are primarily used in cases of severe corneal ulcerations and perforations. Chen et al demonstrated a higher bacteriostatic effect of cyanoacrylates over fibrin glue as well as superior ability to seal corneal wounds.(15) This is the main reason for their preference in using it to treat the sequelae of infectious keratitis.

It is recommended that the use of tissue glue be reserved for perforations less than 3 mm in diameter. Larger defects may be treated with glue, but an increased risk of toxicity from glue entering the anterior chamber or difficulty sealing the wound may be experienced. Different techniques have been described when utilizing cyanoacrylate glue to manage corneal ulcerations and perforations. The size of the perforation, as well as physician preference usually determines which technique is favored. Vote and Elder described the use of cyanoacrylate glue and sterile drape material to achieve good wound closure.(13) Briefly, a section of sterile drape slightly larger than the corneal defect is cut. Glue is applied to one side of the drape material, which is then pressed onto the perforation and allowed to dry.(Figure 2) This technique provides a smooth surface and may be a superior technique for larger perforations since multiple overlapping patches may be used. Alternatively, cyanoacrylate glue may be applied to the defect directly and allowed to air dry. Both techniques require 1–2 mm of epithelial debridement around the perforation. Care should be taken to dry the defect before application of glue. This sometimes requires the anterior chamber to be filled with air to prevent egress of aqueous while applying the glue. A soft bandage contact lens is then placed over the glue or patch for patient comfort and to prevent the glue from dislodging.

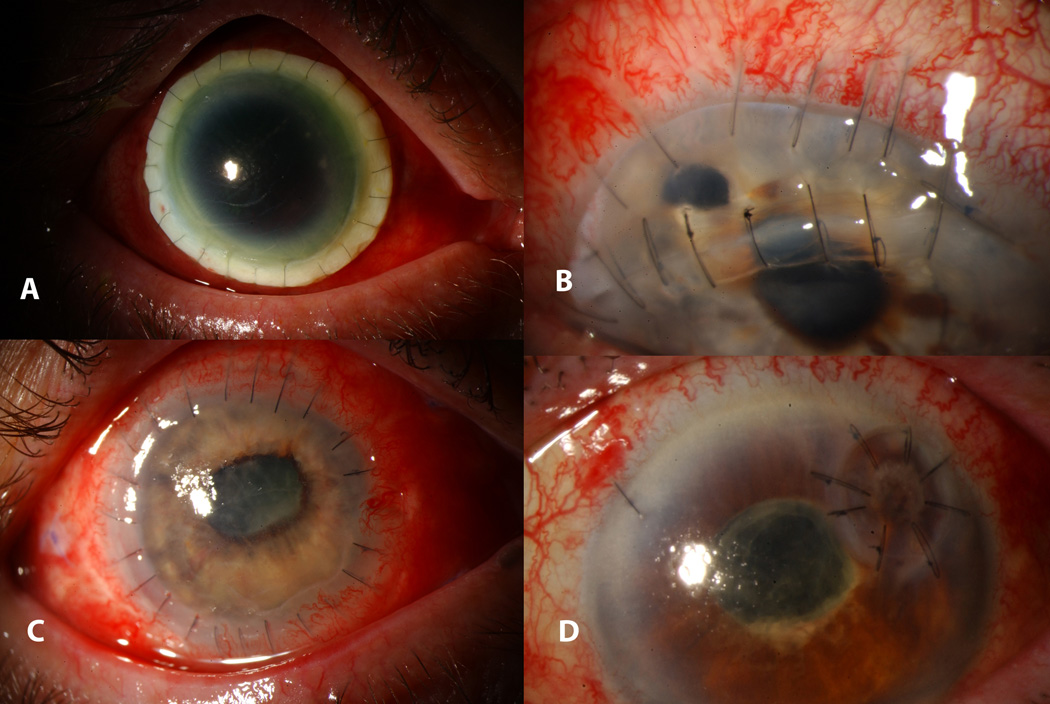

Figure 2.

A. Perforated peripheral corneal ulcer with iris prolapse and flat anterior chamber B. Ulcer status post glue application with arrow pointing to the edge of the circular drape patch and formed anterior chamber.

In addition to the treatment of bacterial ulcerations, Moorthy et al demonstrated that n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue may be a temporary method of stabilization for perforations <1.5 mm related to herpetic keratitis. A little over one third of their patients healed with glue application alone and slightly more than half went on to have a subsequent therapeutic keratoplasty.(16) Furthermore, Garg et al were able to show that cyanoacrylate can also be useful when treating fungal keratitis (17). 42 of 66 eyes treated with glue led to resolution of keratomycosis with subsequent scar formation. In several eyes (38%), multiple glue applications were required. 24% of the eyes showed progressive worsening or lack of improvement and eight required penetrating keratoplasty. Eyes with smaller fungal infiltrates showed better outcomes.

These studies confirm that the application of tissue adhesives, in particular cyanoacrylates, is a useful modality in the treatment of infectious corneal ulcerations. While not always curative, tissue adhesives may help to maintain structural integrity of the globe until a more definitive procedure can be performed.

Amniotic membrane transplantation

Human amniotic membrane is derived from fetal membranes and is composed of three layers – a single epithelial layer (which is removed during processing), a basement membrane, and a stromal layer. Transplantation of amniotic membrane in the setting of infectious corneal ulceration promotes epithelial wound healing, decreases inflammation, and promotes anti-scarring and anti-angiogenic effects on the ocular surface.(18) The mechanism by which amniotic membrane confers its clinical effects is inferred from the biological composition of the membrane as summarized by Tseng and Dua.(18, 19) Cytokines and proteins such as tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines. The stroma may also act as a sink for polymorphonuclear inflammatory cells and lymphocytes, which are then cleared by induced apoptosis. The presence of assorted growth factors in addition to structural components like collagen types IV, V and VII, laminin and fibronectin help facilitate the migration, adhesion, and differentiation of host epithelial cells. This combination of decreased inflammation and accelerated wound healing may play an important part in the decreased scarring seen with the use of AMT in infectious keratitis.

The use of human amniotic membrane to treat conjunctival defects was first proposed by de Rotth in 1940 and later by Lee and Tseng to treat corneal epithelial defects with corneal ulcers in 1997.(20, 21) Since then, ophthalmic literature has described many different techniques of applying human amniotic membranes in the treatment of corneal disease. Most of these techniques require filling the stromal defect with several layers of amniotic membrane epithelial (basement membrane) side up, taking care not to overlap the edges of the defect. This allows epithelialization of the area over the membranes. A much larger “overlay” membrane may then be secured either epithelial or stromal side up with interrupted 10-0 Nylon sutures to provide mechanical protection for the ocular surface.(Figure 3) The technique described by Berguiga involved the use of a sutured AMT first and then sliding additional membranes beneath the overlay to fill the stromal defect.(22)

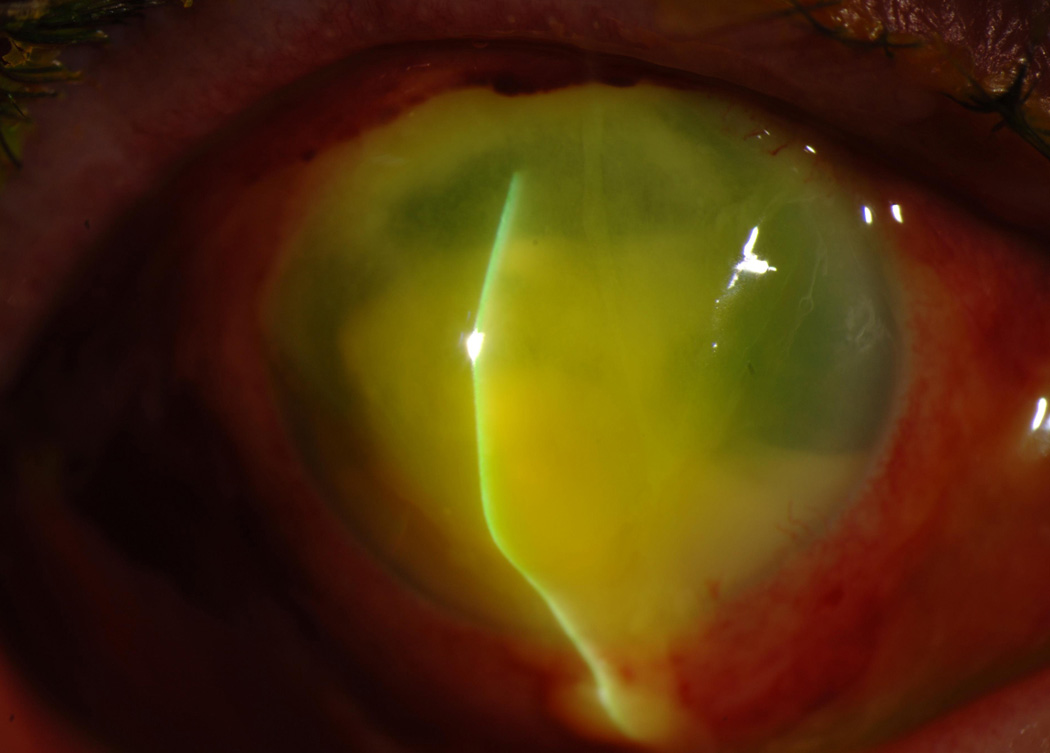

Figure 3.

Multilayer amniotic membrane transplant for severe corneal thinning with descemetocele. The overlay membrane was secured with a running 10-0 Nylon suture.

Kruse et al showed excellent results with multilayer AMT for deep corneal ulcers with 9 of 11 patients showed re-epithelialization with stability of stromal thickness.(23) Similarly, Berguiga et al demonstrated a long-term benefit with 10 of 11 patients treated with multilayer AMT for deep ulcers and descemetoceles as well as non-traumatic perforations showing resolution that persisted for an average of 32 months.(22) More recently, Mohan et al showed an 82.1% success rate of ulcer healing with multilayered amniotic membrane transplantation at 1 month and 75% after 6 months using an “overlay on-inlay” technique.(24) Most recently, however, a large study by Uhlig et al of 108 patients with corneal ulcers showed a much lower success rate of approximately 50% whether an overlay or multilayer approach was used.(25)

The use of a single layered AMT may be sufficient for the treatment of corneal ulcerations lacking depth and significant stromal thinning. This includes the use of sutured membrane as well as self-retaining varieties. A small case series by Sheha et al evaluated the efficacy of early self-retaining AMT using Prokera® (Biotissue, Inc., Miami, Florida) in the management of severe bacterial ulceration.(26) They observed decreased pain and inflammation in all cases in addition to healing of the epithelium and improvement in visual acuity.

Structural integration of multilayer AMT was evaluated by Nubile et al using anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) and confocal microscopy.(27) A significant post-operative increase in corneal thickness was noted on AS-OCT in 20 of 22 eyes with confocal evidence of stroma-derived cells populating the transplanted amniotic membrane inlay. Persistence of amniotic tissue was noted throughout the follow up period of 12 months. These findings are significant in that they demonstrate true assimilation of amniotic membrane tissue with healing corneal stroma.

Nearly all patients throughout each study showed some degree of improvement with decreased inflammation, pain, and improved corneal healing. Among these studies, complete healing without recurrence ranged from 48% to 91%. Long term prognosis of these eyes were highly dependent on the severity of the initial disease as well as achieving appropriate control of the underlying pathological process.

Pedicle conjunctival graft

Using conjunctival tissue to heal chronic corneal ulceration was popularized by Gundersen in 1958 but his sentinel paper references their first application by Scholer in 1877 for corneal disease.(28) He described both sliding and pedunculated grafts to treat a diverse variety of corneal pathology, including ulcers.(29) Conjunctival flaps are not commonly used currently but have significant benefits, especially in the treatment of peripheral infectious keratitis. They provide vascularized tissue to the infected area to supply humoral and cellular immunity while providing serum growth factors to enhance healing. They also act as a biological bandage reducing pain and stromal necrosis.

Either total or partial flaps may be performed depending on the extent of the corneal pathology.(30) In either case, the corneal area to be transplanted is de-epithelialized. A peritomy is performed and the conjunctiva without Tenon’s capsule is mobilized over the cornea. It is sutured into place using non-absorbable sutures, which are subsequently removed. Debulking of the necrotic and infected corneal tissue may be performed prior to suturing the graft to decrease the infectious load for faster healing. Sun et al reported 100% success in treating fungal ulcers using this technique with minimal complications.(31) Another modification of the basic technique is the creation of a superior forniceal conjunctival advancement pedicle (SFCAP). In this technique, a thicker flap is used and Tenon’s capsule and a prominent blood vessel are included in the flap. The flap is then sutured to the edges of the corneal ulcer. Unlike the thin “Gundersen” flaps that cannot be used in perforated eyes, this technique was successfully employed by Sandinha and colleagues in 20 ulcers that were either perforated or impending perforation.(32)

A large prospective randomized study by Abdulhalim and colleagues compared the outcomes of bipedicle conjunctival flaps to AMT in non-viral infectious keratitis (bacterial, fungal, and Acanthamoeba) that was resistant to medical therapy.(33) They had a success rate of 90% in each group with no significant differences between the two modalities. The two failures in each group were related to existing perforated ulcers or descemetocele at the time of surgery. Zhou and colleagues had similar results in 56 eyes with refractory corneal ulcers.(34) The major complications were flap retraction and four patients needing lamellar keratoplasty due to recurrent fungal ulcers under the flap.

Corneal transplantation

A global survey of eye banking revealed that 20% of all corneal transplants done worldwide are for infectious keratitis, and that the primary indication for transplantation in 24% of countries is infectious keratitis.(35) As more potent antibacterial agents are increasingly available, the incidence of transplantation to control bacterial infections is decreasing. However, this is not true for fungal infections where a large percentage of ulcers still require surgical management.(7) Corneal transplantation works by completely removing the infected corneal tissue as in most cases of bacterial keratitis. However, in cases of fungal or Acanthamoeba infections, it may not be possible to completely eliminate the entire infected area. Transplantation in these conditions is therefore used to debulk the infection and allow the antimicrobials to eradicate the rest.(36)

Various types of corneal transplantation have been used as therapeutic modalities to control infections. Penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) is the most common procedure done for infectious keratitis.(37) The goal of the surgery is to removal all the infected corneal tissue and replace it with healthy cornea. The surgery is very successful in eradicating bacterial keratitis with cure rates of over 90% reported in the literature.(38–40) However, the success rate diminishes significantly in fungal ulcers. Xie and colleagues had excellent results in their study where they performed therapeutic PKP on 108 patients with fungal keratitis. They had a recurrence rate of 7.4% and 4 of these eyes had to be enucleated due to endophthalmitis. However, these results have not been replicated by others. A large study of 180 cases of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty in Nepal showed a recurrence rate of infection in 26% of cases of fungal keratitis while the recurrence rate was only 6% in bacterial infections.(39) An even larger study of 506 eyes from Northern India by Sharma et al found that the highest anatomic success rate was for bacterial keratitis at 94%, followed by fungal keratitis at 89% while mixed bacterial and fungal organisms had a success rate of only 71%.(40) Unfortunately, the visual acuity results were poor with only 15% of patients with vision >6/60 at the end of a year. These results were slightly better at 20% if the graft was < 9 mm and only 5% if the graft was > 11 mm. Ramamurthy and colleagues retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of repeat keratoplasty (PKP or endothelial (EK) grafts) for visual rehabilitation of failed therapeutic transplants in 112 eyes who had undergone the initial transplant for infectious keratitis.(41) They found that there were significantly more clear grafts after PKP than EK at one year as well as five years although the PKP grafts had a higher incidence of rejection. Nearly 50% of each group had vision ≥20/40 at 1 year. This confirms the fact that eradication of the infection is the goal of the initial therapeutic keratoplasty and that visual rehabilitation is possible with subsequent surgery.

While full thickness corneal transplants still remain the gold standard, anterior lamellar keratoplasty (ALK) is increasingly being used to treat infections that are relatively superficial.(42–45) Although technically more challenging, ALK theoretically decreases the risk of graft rejection and endothelial cell loss, and decreases the risk of introducing infectious material into the anterior chamber since the Descemet membrane is not breached. However, there is a risk of recurrence of the infection at the interface due to incomplete removal of the infectious organisms.(42) Gao and colleagues published their series of ALK in 23 patients with deep fungal ulcers that did not respond to medical therapy for at least two weeks.(42) They had good success rates with recurrence of fungal infection in 2 cases and graft rejection in only one case. Sarnicola et al performed ALK in 11 eyes for Acanthamoeba and had no recurrences and no rejections.(43) Innovative methods of obtaining lamellar tissue have been described including using lenticules from small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) surgery used for refractive correction.(46, 47)

Peripheral corneal ulcers offer a unique challenge, as central circular corneal transplants may not encompass the entire infectious area while removing a large amount of uninvolved central corneal tissue. In addition, grafts close to the limbus have a high risk of rejection. Therefore, numerous alternate graft shapes and sizes have been described (Figure 4) for these conditions including crescent, horseshoe, as well as small-diameter circular grafts.(37, 48, 49)

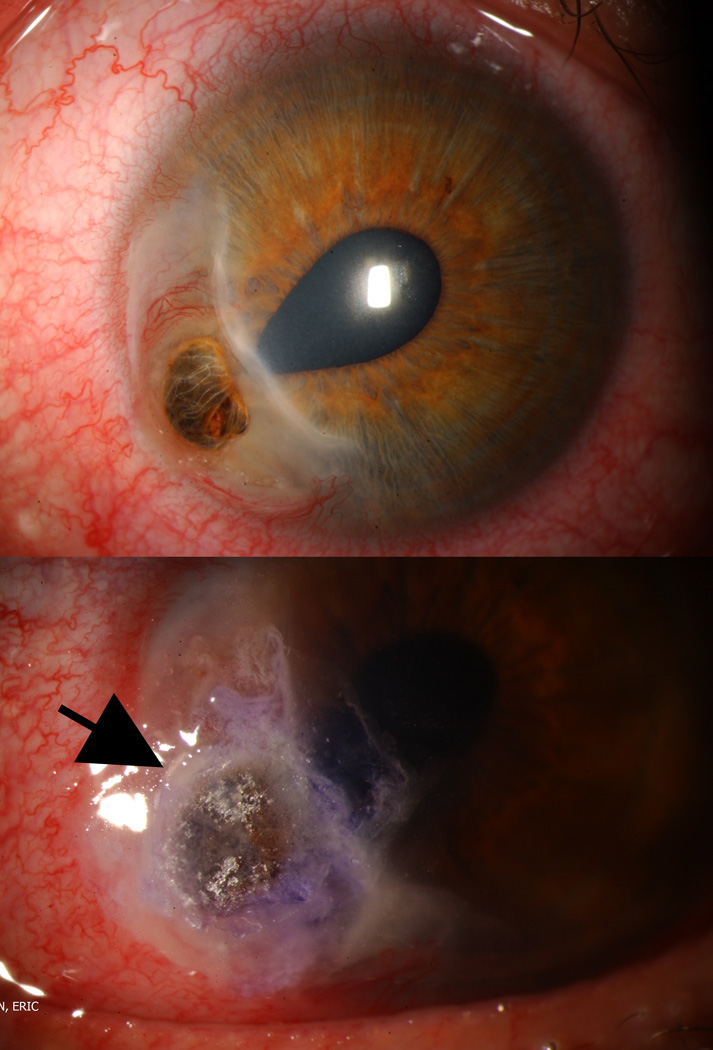

Figure 4.

Various keratoplasty techniques used in the management of severe corneal ulceration and perforation. (A) Keratolimbal graft due for a "wall to wall" fungal ulcer. (B) Crescent shaped graft for peripheral melt. (C) Oversized penetrating keratoplasty for large corneal ulcer. (D) Circular patch graft for fungal ulcer in clear corneal cataract incision.

Conclusion

Infectious keratitis is a challenging condition requiring ophthalmologists to use an armamentarium of therapies to successfully manage the infectious process and maintain structural integrity of the eye. In a number of cases, surgical intervention is needed to control the infection or its sequelae. While bacterial keratitis typically has good outcomes with surgery, fungal infections have a much more guarded prognosis and polymicrobial infections have an exceptionally poor prognosis. The treatment of choice would depend on the size, location, and etiology of the infection.

In small, peripheral ulcers, gluing can be a definitive therapy. Healing of the cornea occurs as fibrovascular tissue grows under the glue and dislodges the glue. Larger ulcers may require a plastic drape patch glued to the edges of the ulcerated area to maintain globe integrity. In central corneal ulcers, glue can be used as a temporizing measure until a more definitive therapy can be performed. Similar to glue, AMT can provide structural support in areas of corneal ulceration; it differs from tissue adhesives in that it becomes incorporated in the corneal stroma. Additionally, AMT provides anti-inflammatory and healing factors that may hasten epithelialization and reduce scarring. Another option for peripheral ulcers is a conjunctival pedicle or sliding graft. This allows the body’s immune system to clear the infectious process while the serum growth factors help the cornea heal. Finally, larger, peripheral ulcers may require a corneal patch graft. Numerous types of grafts can be performed including crescent and horseshoe shapes but these are technically more challenging.

Central and larger corneal infections require either central penetrating or lamellar transplants. Penetrating keratoplasty has higher success rates in terms of infection control and clarity of vision. However, lamellar grafts have lower intra-operative and post-operative complications. Eliminating the entire infected area theoretically results in a higher success rate.

In summary, infectious keratitis often needs surgical intervention to control the infection and maintain structural integrity. The type of surgical intervention performed depends on the location, size and etiology of the infection and must be adapted to the individual patient’s needs. While no novel techniques have been developed recently, incremental improvements in the existing surgical modalities have made surgical intervention of infectious keratitis safer and more effective.

Key Points.

Success rates of surgical therapies are best for bacterial corneal infections and worst for fungal infections

Unresponsive corneal infections, impending perforations, and perforations are the usual indications for surgical intervention

Definitive therapy of peripheral corneal ulcers may include corneal gluing, multilayer amniotic membranes, conjunctival flaps and corneal transplants

Central corneal ulcers usually require corneal transplantation for definitive therapy although any of the other modalities may be used as a temporizing measure

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported in part by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Neither speaker has any conflicts of interest

Reference Section

- 1.Lim M, Goldstein MH, Tuli S, Schultz GS. Growth factor, cytokine and protease interactions during corneal wound healing. OculSurf. 2003;1(2):53–65. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez-Camarena JC, Graue-Hernandez EO, Ortiz-Casas M, Ramirez-Miranda A, Navas A, Pedro-Aguilar L, et al. Trends in Microbiological and Antibiotic Sensitivity Patterns in Infectious Keratitis: 10-Year Experience in Mexico City. Cornea. 2015;34(7):778–785. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duan R, de Vries RD, Osterhaus AD, Remeijer L, Verjans GM. Acyclovir-resistant corneal HSV-1 isolates from patients with herpetic keratitis. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(5):659–663. doi: 10.1086/590668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fernandes M, Vira D, Dey M, Tanzin T, Kumar N, Sharma S. Comparison Between Polymicrobial and Fungal Keratitis: Clinical Features, Risk Factors, and Outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(5):873–881. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.07.028. This article demonstrated that polymicrobial keratitis was not only more common but more challenging to treat and frequently required early penetrating keratoplasty. This is important to remind treating ophthalmologist to consider a co-infection with bacteria and fungus in patients who are responding poorly to medical management alone.

- 5. Pinheiro R, Panfil C, Schrage N, Dutescu RM. The Impact of Glaucoma Medications on Corneal Wound Healing. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(1):122–127. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000279. This article showed that Xalatan and BAC had deleterious effects on the corneal surface while Monoprost delayed corneal healing

- 6. Bhadange Y, Das S, Kasav MK, Sahu SK, Sharma S. Comparison of culture-negative and culture-positive microbial keratitis: cause of culture negativity, clinical features and final outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(11):1498–1502. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306414. This study indicates that fewer major surgical procedures are needed for culutre negative keratitis, but both culture negative and culture positive keratitis had similar outcomes after treatment.

- 7. Lin TY, Yeh LK, Ma DH, Chen PY, Lin HC, Sun CC, et al. Risk Factors and Microbiological Features of Patients Hospitalized for Microbial Keratitis: A 10-Year Study in a Referral Center in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(43):e1905. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001905. This study concluded that hospitalized patients who developed microbial keratitis were most likely due to contact lens wear, followed by ocular and systemic disease, and trauma. Pseudomonas was the most commonly isolated organism.

- 8.Keay LJ, Gower EW, Iovieno A, Oechsler RA, Alfonso EC, Matoba A, et al. Clinical and Microbiological Characteristics of Fungal Keratitis in the United States, 2001–2007: A Multicenter Study. Ophthalmology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lalitha P, Prajna NV, Manoharan G, Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Das M, et al. Trends in bacterial and fungal keratitis in South India, 2002–2012. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(2):192–194. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305000. Large study of over 8000 positive corneal smears showed that the incidence of bacterial keratitis was decreasing while that of fungal keratitis was increasing in South India.

- 10.Gower EW, Keay LJ, Oechsler RA, Iovieno A, Alfonso EC, Jones DB, et al. Trends in fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001 to 2007. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(12):2263–2267. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuli SS, Iyer SA, Driebe WT., Jr Fungal keratitis and contact lenses: an old enemy unrecognized or a new nemesis on the block? Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33(6 Pt 2):415–417. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e318157e999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan J, Wechsler AW, Watson S. Long-term adhesion of cyanoacrylate on human cornea. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2014;42(8):791–793. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vote BJ, Elder MJ. Cyanoacrylate glue for corneal perforations: a description of a surgical technique and a review of the literature. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2000;28(6):437–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2000.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kara S, Arikan S, Ersan I, Taskiran Comez A. Simplified technique for sealing corneal perforations using a fibrin glue-assisted amniotic membrane transplant-plug. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2014;2014:351534. doi: 10.1155/2014/351534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen WL, Lin CT, Hsieh CY, Tu IH, Chen WY, Hu FR. Comparison of the bacteriostatic effects, corneal cytotoxicity, and the ability to seal corneal incisions among three different tissue adhesives. Cornea. 2007;26(10):1228–1234. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181506129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moorthy S, Jhanji V, Constantinou M, Beltz J, Graue-Hernandez EO, Vajpayee RB. Clinical experience with N-butyl cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in corneal perforations secondary to herpetic keratitis. Cornea. 2010;29(9):971–975. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181cbfa13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg P, Gopinathan U, Nutheti R, Rao GN. Clinical experience with N-butyl cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in fungal keratitis. Cornea. 2003;22(5):405–408. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tseng SC, Espana EM, Kawakita T, Di Pascuale MA, Li W, He H, et al. How does amniotic membrane work? OculSurf. 2004;2(3):177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dua HS, Gomes JA, King AJ, Maharajan VS. The amniotic membrane in ophthalmology. SurvOphthalmol. 2004;49(1):51–77. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de RÖ TA. PLastic repair of conjunctival defects with fetal membranes. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1940;23(3):522–525. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SH, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation for persistent epithelial defects with ulceration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123(3):303–312. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berguiga M, Mameletzi E, Nicolas M, Rivier D, Majo F. Long-term follow-up of multilayer amniotic membrane transplantation (MLAMT) for non-traumatic corneal perforations or deep ulcers with descemetocele. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2013;230(4):413–418. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1328394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kruse FE, Rohrschneider K, Volcker HE. Multilayer amniotic membrane transplantation for reconstruction of deep corneal ulcers. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(8):1504–1510. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90444-X. discussion 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohan S, Budhiraja I, Saxena A, Khan P, Sachan SK. Role of multilayered amniotic membrane transplantation for the treatment of resistant corneal ulcers in North India. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34(3):485–491. doi: 10.1007/s10792-013-9834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uhlig CE, Frings C, Rohloff N, Harmsen-Aasman C, Schmitz R, Kiesel L, et al. Long-term efficacy of glycerine-processed amniotic membrane transplantation in patients with corneal ulcer. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(6):e481–e487. doi: 10.1111/aos.12671. This large study showed a higher rate of recurrence and less improvement in visual acuity in patients treated with amniotic membrane for corneal ulcers than was previously reported in the literature.

- 26.Sheha H, Liang L, Li J, Tseng SC. Sutureless amniotic membrane transplantation for severe bacterial keratitis. Cornea. 2009;28(10):1118–1123. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181a2abad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nubile M, Dua HS, Lanzini M, Ciancaglini M, Calienno R, Said DG, et al. In vivo analysis of stromal integration of multilayer amniotic membrane transplantation in corneal ulcers. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(5):809–822. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gundersen T. Conjunctival flaps in the treatment of corneal disease with reference to a new technique of application. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1958;60(5):880–888. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940080900008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor JW. Treatment of Perforating Wounds of Eyeball with Report of Cases. The Journal of the Florida Medical Association. 1921;VII(9):134–137. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alino AM, Perry HD, Kanellopoulos AJ, Donnenfeld ED, Rahn EK. Conjunctival flaps. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(6):1120–1123. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)96017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun GH, Li SX, Gao H, Zhang WB, Zhang MA, Shi WY. Clinical observation of removal of the necrotic corneal tissue combined with conjunctival flap covering surgery under the guidance of the AS-OCT in treatment of fungal keratitis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2012;5(1):88–91. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2012.01.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandinha T, Zaher SS, Roberts F, Devlin HC, Dhillon B, Ramaesh K. Superior forniceal conjunctival advancement pedicles (SFCAP) in the management of acute and impending corneal perforations. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(1):84–89. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Abdulhalim BE, Wagih MM, Gad AA, Boghdadi G, Nagy RR. Amniotic membrane graft to conjunctival flap in treatment of non-viral resistant infectious keratitis: a randomised clinical study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(1):59–63. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305224. This study compared the use of a conjunctival flap and amniotic membrane graft in the treatment of infectious keratitis. This study showed equivocal results between the two groups with good healing except for cases with larger perforations which were more likely to require penetrating keratoplasty.

- 34.Zhou Q, Long X, Zhu X. Improved conjunctival transplantation for corneal ulcer. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2010;35(8):814–818. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, Aldossary M, Acquart S, Cognasse F, et al. Global Survey of Corneal Transplantation and Eye Banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4776. This study identified the number of corneal transplants and corneal procurements per capita in each country. A global shortage of tissue was noted with only 1 cornea available for 70 needed and demonstrates the importance of efforts to find solutions to this shortage.

- 36.Sharma N, Sachdev R, Jhanji V, Titiyal JS, Vajpayee RB. Therapeutic keratoplasty for microbial keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21(4):293–300. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833a8e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokogawa H, Kobayashi A, Yamazaki N, Masaki T, Sugiyama K. Surgical therapies for corneal perforations: 10 years of cases in a tertiary referral hospital. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:2165–2170. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S71102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yalniz-Akkaya Z, Burcu A, Dogan E, Onat M, Ornek F. Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty for infectious and non-infectious corneal ulcers. Int Ophthalmol. 2015;35(2):193–200. doi: 10.1007/s10792-014-9931-y. This study demonstrates the effective role of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty as a method to treat serious corneal ulcerations.

- 39. Bajracharya L, Gurung R. Outcome of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty in a tertiary eye care center in Nepal. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:2299–2304. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S92176. This study showed the importance as well as the complications associated with the use of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty in the treatment of severe infectious keratitis.

- 40.Sharma N, Jain M, Sehra SV, Maharana P, Agarwal T, Satpathy G, et al. Outcomes of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty from a tertiary eye care centre in northern India. Cornea. 2014;33(2):114–118. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ramamurthy S, Reddy JC, Vaddavalli PK, Ali MH, Garg P. Outcomes of Repeat Keratoplasty for Failed Therapeutic Keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;162:83–88. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.11.004. This study showed that repeat penetrating keratoplasty can be beneficial to visual rehabilitation after a failed therapeutic keratoplasty.

- 42.Gao H, Song P, Echegaray JJ, Jia Y, Li S, Du M, et al. Big bubble deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty for management of deep fungal keratitis. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014:209759. doi: 10.1155/2014/209759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sarnicola E, Sarnicola C, Sabatino F, Tosi GM, Perri P, Sarnicola V. Early Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty (DALK) for Acanthamoeba Keratitis Poorly Responsive to Medical Treatment. Cornea. 2016;35(1):1–5. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000681. This case series showed that therapeutic DALK may be successful for early cases of acanthamoeba. Recurrence of infection was not noted even if deep margins were positive for infection.

- 44.Anshu A, Parthasarathy A, Mehta JS, Htoon HM, Tan DT. Outcomes of therapeutic deep lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty for advanced infectious keratitis: a comparative study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(4):615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park JC, Habib NE. Tectonic lamellar keratoplasty: simplified management of corneal perforations with an automated microkeratome. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015;50(1):80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.09.011. This case series demonstrated a new technique to simplify the preparation of host and donor corneas during tectonic lamellar keratoplasties.

- 46. Wu F, Jin X, Xu Y, Yang Y. Treatment of corneal perforation with lenticules from small incision lenticule extraction surgery: a preliminary study of 6 patients. Cornea. 2015;34(6):658–663. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000397. This study demonstrated that lenticules from extracted small incision lenticule extraction may be a good source to treat corneal perforations which could lessen the burden on eye banks providing tissues for therapeutic keratoplasties.

- 47. Bhandari V, Ganesh S, Brar S, Pandey R. Application of the SMILE-Derived Glued Lenticule Patch Graft in Microperforations and Partial-Thickness Corneal Defects. Cornea. 2016 doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000741. This case series demonstrated that lenticules from small incision lenticule extraction were safe and inexpensive sources of tissues for patching small perforations and corneal defects.

- 48. Samarawickrama C, Goh R, Vajpayee RB. "Copy and Fix": A New Technique of Harvesting Freehand and Horseshoe Tectonic Grafts. Cornea. 2015;34(11):1519–1522. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000599. This case series describes a novel technique to prepare donor corneal tissue in cases that require irregular shaped grafts such as crescent and horseshoe configurations.

- 49. Fernandes M, Vira D. Patch Graft for Corneal Perforation Following Trivial Trauma in Bilateral Terrien's Marginal Degeneration. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22(2):255–257. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.151873. This case report describes the successful use of a patch graft in a young female patient with Terrien’s marginal degeneration.