Abstract

Background

Partner notification (PN) for sexually transmissible infections (STIs) is a vital STI control method. The most recent evaluation of PN practices in the United States, conducted in 1999, indicated that few STI patients were offered PN services. The objectives of this study were to obtain a preliminary understanding of the current provision of PN services in HIV/STI testing sites throughout the US and to determine the types of PN services available.

Methods

A convenience sample of 300 randomly selected testing sites was contacted to administer a phone survey about PN practices. These sites were from a large database maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sites were eligible to participate if they provided testing services for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV or syphilis and were not hospitals or Planned Parenthood locations.

Results

Of the 300 eligible sites called, 79 sites were successfully reached, of which 74 agreed to participate, yielding a response rate of 24.7% and a cooperation rate of 93.7%. Most surveyed testing sites provided some form of PN service (anonymous or non-anonymous) on site or through an affiliate for chlamydia (100%), gonorrhoea (97%), HIV (91%) and syphilis (96%) infection. Anonymous PN services were available at 67–69% of sites. Only 6–9% of sites offered Internet-based PN services.

Conclusions

Most surveyed testing sites currently offer some type of PN service for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV or syphilis infection. However, approximately one-third of surveyed sites do not offer anonymous services. Novel, Internet-based methods may be warranted to increase the availability of anonymous services.

Additional keywords: HIV/STI testing, patient-delivered partner therapy

Introduction

Partner notification (PN) is a core public health intervention for the prevention and control of sexually transmissible infections (STIs). PN consists of informing the sexual partners of recently offering them appropriate counselling, testing and treatment.1 PN services initially began as a control strategy for syphilis in the 1930s.2 Since then, PN programs have expanded to include chlamydia, gonorrhoea and HIV infection.

Traditionally, PN services have relied on either patients to contact their partners directly (patient referral) or on health providers, such as nurses or physician assistants, to do so anonymously on patients’ behalf (provider referral).3 Over the last decade, several non-traditional methods have been developed to facilitate the notification process. In patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT), chlamydia- and gonorrhoea-positive patients are provided with prescriptions or medications to give to their sexual partners directly.4 Other methods involve anonymous notification via email, text messaging or electronic postcards (e-cards).5 These electronic methods are sometimes provider-initiated and other times patient-initiated through Internet applications. Some of these methods have only recently been put into practice. The use of PDPT, for example, was legalised in several states over the past several years.6

PN services have become an essential component of STI control efforts in the United States (US). However, the most recent evaluation of PN activities in the US indicated that provider-assisted PN services were offered to only a minority of patients with chlamydia (17%), gonorrhoea (12%) and HIV (52%).7 Furthermore, STI diagnoses and subsequent PN efforts take place in a variety of clinical settings, ranging from publicly funded general care clinics to private HIV/STI specialty clinics. There are currently no national guidelines offering standardised protocols for PN service provision in these various settings.3 PN programs are thus decentralised, varied in protocol and frequency of use, and heterogeneous in terms of the level of care offered. No comprehensive assessment of current PN practices throughout the US has been conducted since 1998 or published since 2003.7 Little is known about how the scope of PN programs has changed since the implementation of non-traditional PN methods, including which of these methods are commonly offered and how they are currently put into practice.

The reliance on PN as an important STI control strategy suggests that a more detailed and recent assessment of PN practices is crucial. Our research objective was to gain a preliminary understanding of the current PN system in the US. We administered a telephone questionnaire to a small sample of HIV/STI testing sites throughout the country to identify commonly used notification methods (both anonymous and non-anonymous) for patients with chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV and syphilis infection.

Methods

The National Prevention Information Network (NPIN), part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), maintains a large database of >40 000 organisations or agencies that offer HIV/STI testing services in the US and its territories.8 We used a convenience sample of 300 randomly selected testing sites in this database to administer a phone survey about PN practices. Testing sites were eligible to complete the phone survey if they: (i) were located within the 50 states; (ii) offered testing services for at least one of the following infections: chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV or syphilis; and (iii) were not Planned Parenthood locations or hospitals. Planned Parenthood locations were ineligible due to an organisational no-survey policy. Hospitals were excluded because we wished to survey testing sites that had protocol-driven PN procedures.

Trained research staff called testing sites during the months of July and August 2012 and asked to speak to site directors, administrators or a knowledgeable appointed staff member. Each testing site was called a minimum of twice per day over 2 days. Sites were considered unresponsive when an appropriate staff member was not reached during these call attempts. Calls were appropriately distributed over weekday working hours. The survey instrument was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt from human research.

We initially tested the survey instrument on 17 randomly selected sites in the NPIN database and made subsequent edits and refinements (the data from these 17 sites were not included in the final analysis). The information collected on the survey focussed on three domains: (i) testing site demographic information, including testing services offered and staff composition; (ii) the types of PN services offered for each infection; and (iii) the availability of PN services at the testing site and/or an affiliate. Patients may be offered PN services directly on site or may be referred to an affiliate to receive PN services. In this study, affiliates were entities that provided PN services on behalf of a testing site when the testing site did not offer PN services directly on site. Affiliates included county, district, state or regional health departments that provided PN services.

To identify the types of PN services offered, we asked respondents to determine whether their site’s PN methods corresponded to any of four anonymous or any of three non-anonymous notification services. Anonymous services are those in which patient identities are not disclosed to notified partners, whereas with non-anonymous services, patient identities are discernible to their notified partners. These seven PN methods were synthesised from the responses initially gathered from the pilot testing. The anonymous services included: (i) phone calls; (ii) field visits to partners (at home, work, etc.); (iii) mailed letters; and (iv) Internet-based notification, defined as the provider-initiated use of email and/ or social media to find and contact partners anonymously. In these four PN methods, trained clinic providers, such as nurses or physician assistants, contact patients’ partners through these various venues without disclosing patient identities and offer partners information about STI testing and treatment services. Non-anonymous patient referral services included: (v) patient counselling for referral of partners; (vi) patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT); and (vii) site referral cards containing information about services, to be delivered to partners by patients. When counselling for partner referral, clinic providers encourage patients to notify their partners themselves and offer patients counselling and guidance on how to inform partners. Providers may also give patients STI medications (PDPT) and/ or referral cards to give to their partners. Although PDPT may not necessarily be equivalent to PN, survey respondents recognised that PDPT could serve as a form of PN because patients inherently notify their partners when delivering STI medications to them. We thus categorised PDPT as a form of non-anonymous PN in our analyses. Respondents were given the opportunity to describe notification methods that did not correspond to one of these seven options. Lastly, we asked participants about: (i) their awareness and use of inSPOT (www.inspot.org); and (ii) awareness and acceptability of a new Internet-based site, 'So They Can Know’ (www.sotheycanknow.org), both free-of-cost websites that patients can use to notify partners anonymously (patient-initiated, Internet-based notification).

Descriptive statistics were used to examine testing site demographics and the proportion of sites offering each type of PN service per STI. We stratified our analyses by whether PN services were provided directly on site, through a PN affiliate, or both. In these analyses, we considered the overall availability of PN services to be unknown if: (1) no services were offered on site and the services at the affiliate were unknown, or vice versa; or (2) respondents were unaware of the PN protocols used both on site and at their affiliate.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (version 11, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

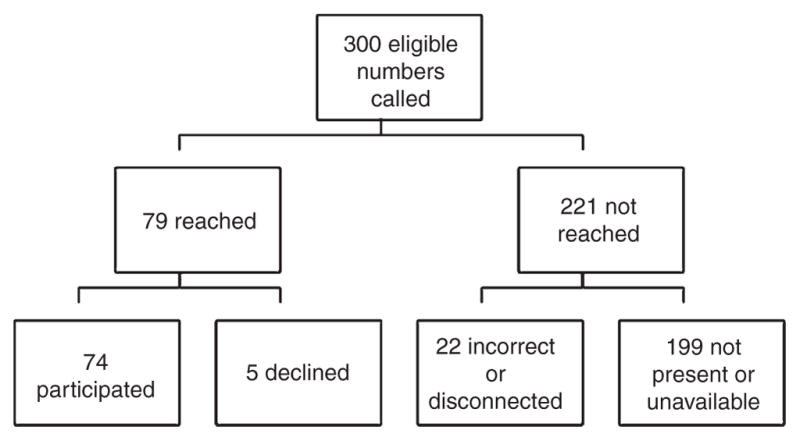

Of the 300 eligible sites called, 79 sites were successfully reached and 74 completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 24.7% (Fig. 1). The cooperation rate, defined as the proportion of sites that completed the survey out of all eligible sites that were successfully reached, was 93.7%.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of survey response rates.

Table 1 summarises the job title of survey respondents and general demographic information of participating sites. Eighty per cent of testing sites reported having an affiliate that provides some form of PN service on the sites’ behalf. One testing site relied exclusively on an affiliate for PN, whereas 78% (58 of 74) provided PN services both on site and through an affiliate. Of testing sites that reported having an affiliate, a significant proportion was unaware of the affiliate’s PN protocols used for chlamydia (36%), gonorrhoea (44%), HIV (47%) and syphilis (47%) infection. One respondent was unaware of the PN protocols used on site for HIV infection.

Table 1.

Job title of survey respondents and demographic information about participating sites STI, sexually transmissible infection; PN, partner notification

| n | No. (%) of survey respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Survey respondent job title | 69 | |

| Site Director | 19 (28) | |

| STI/HIV Program Manager | 11 (16) | |

| Communicable disease, public health or STI/HIV nurse | 15 (22) | |

| Nursing Director, Manager or Supervisor | 6 (9) | |

| Disease Intervention Specialist | 2 (3) | |

| OtherA | 16 (23) | |

| Type of testing site | 74 | |

| County or city health department clinic | 43 (58) | |

| Community, family or wellness health centre | 22 (30) | |

| Family planning, reproductive health or women’s clinic | 5 (7) | |

| STI/HIV speciality clinic | 4 (5) | |

| Geographic location | 74 | |

| Midwest | 19 (26) | |

| North-east | 11 (15) | |

| South | 29 (39) | |

| West | 15 (20) | |

| Median no. of full-time personnel involved in STI/HIV-related work (range) | 70 | 3 (1–40) |

| Median no. of full-time personnel providing PN services (range) | 63 | 3 (0–40) |

| At least one of the following full-time personnel provides PN services on siteB | 62 | |

| Nurses | 49 (79) | |

| Physicians | 10 (16) | |

| Disease Intervention Specialists | 3 (5) | |

| Physician’s Assistants | 18 (29) | |

| OtherC | 11 (18) | |

| PN service provider | 74 | |

| On-site personnel only | 15 (20) | |

| Affiliate personnel only | 1 (1) | |

| Both | 58 (78) | |

| Unaware of affiliate’s PN protocols for a STID | ||

| Chlamydia | 28 | 10 (36) |

| Gonorrhoea | 32 | 14 (44) |

| HIV | 53 | 25 (47) |

| Syphilis | 47 | 22 (47) |

| Average no. of patients seen for testing per year | 74 | |

| <1000 | 43 (58) | |

| 1000–1999 | 12 (16) | |

| 2000–2999 | 5 (7) | |

| ≥3000 | 7 (9) | |

| Unknown | 7 (9) | |

| Average no. of chlamydia diagnoses per year | 74 | |

| No testing services available | 4 (5) | |

| <50 | 26 (35) | |

| 50–99 | 9 (12) | |

| 100–149 | 6 (8) | |

| ≥150 | 12 (16) | |

| Unknown | 17 (23) | |

| Average no. of gonorrhoea diagnoses per year | 74 | |

| No testing services available | 2 (3) | |

| <10 | 32 (43) | |

| 10–19 | 10 (14) | |

| 20–29 | 2 (3) | |

| ≥30 | 12 (16) | |

| Unknown | 16 (22) | |

| Average no. of HIV diagnoses per year | 74 | |

| No testing services available | 4 (5) | |

| <5 | 39 (53) | |

| 5–10 | 4 (5) | |

| 10–15 | 2 (3) | |

| ≥15 | 9 (12) | |

| Unknown | 16 (22) | |

| Average no. of syphilis diagnoses per year | 74 | |

| No testing services available | 4 (5) | |

| <5 | 44 (59) | |

| 5–10 | 2 (3) | |

| 10–15 | 5 (7) | |

| ≥15 | 4 (5) | |

| Unknown | 15 (20) |

Includes one assistant director, one Chief Executive Officer, one clinical coordinator, two family planning coordinators, one HIV case manager, two PN service coordinators, one reproductive health clinic coordinator, one STI counsellor and one testing coordinator.

Percentages exceed 100 because some respondents reported having more than one type of personnel providing PN services.

Includes medical assistants, counsellors, administrative staff, social workers, health educators and interpreters.

Includes respondents: (i) that offered testing services for the sexually transmissible infection (STI) of interest; (ii) that reported having an affiliate; and (iii) whose affiliate provided PN services for the STI of interest.

Availability of services

Most surveyed testing sites provided some form of PN service (anonymous or non-anonymous) directly on site and/or through an affiliate for chlamydia (100%), gonorrhoea (97%), HIV (91%) and syphilis (96%) infection (Table 2). However, the proportion of sites specifically offering some form of anonymous PN service directly on site and/or through an affiliate was ~67%, 69%, 69% and 69% for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV and syphilis infection, respectively. Relative to anonymous PN, non-anonymous PN services were available at higher proportions for chlamydia (97%), gonorrhoea (94%), HIV (80%) and syphilis (87%) infection. Overall, anonymous PN service availability could not be assessed for 10%, 11%, 29% and 23% of sites that tested for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV and syphilis infection, respectively.

Table 2.

Number of respondentsA offering partner notification (PN) services on site and/or through an affiliate, by type of PN

| n | No. (%) of survey respondents | No. (%) of unknownB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any PN service | Non-anonymous PN | Anonymous PN | |||

| Chlamydia | 70 | 70 (100) | 68 (97) | 47 (67) | 7 (10) |

| Gonorrhoea | 72 | 70 (97) | 68 (94) | 50 (69) | 8 (11) |

| HIV | 70 | 64 (91) | 56 (80) | 48 (69) | 20 (29) |

| Syphilis | 70 | 67 (96) | 61 (87) | 48 (69) | 16 (23) |

Excludes respondents that did not provide testing services for the sexually transmissible infection (STI) of interest.

Respondents that were unaware of the availability of non-anonymous and/or anonymous PN services offered directly on site and/or at their affiliate.

Table 3 presents the availability of PN services throughout surveyed sites by the location of the provision of services. The majority of testing sites offered non-anonymous PN services directly on site (90–100%), whereas anonymous services were available on site at approximately half of testing sites (41–56%). In contrast, the availability of anonymous services among affiliates (33–49%) was considerably higher relative to non-anonymous services (4–9%), However, 24%, 30%, 50% and 45% of respondents with an affiliate could not provide information regarding the affiliate’s PN services available for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV and syphilis infection, respectively.

Table 3.

Number of respondentsA offering partner notification (PN) services, by location and type of PN

| n | No. (%) of survey respondents | No. (%) of unknownB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any PN service | Non-anonymous PN | Anonymous PN | |||

| On-site servicesC | |||||

| Chlamydia | 70 | 70 (100) | 68 (97) | 37 (53) | 1 (1) |

| Gonorrhoea | 72 | 70 (97) | 68 (94) | 40 (56) | 0 |

| HIV | 69 | 57 (83) | 54 (78) | 28 (41) | 1 (1) |

| Syphilis | 69 | 62 (90) | 59 (86) | 31 (45) | 0 |

| Services at affiliatesD | |||||

| Chlamydia | 54 | 18 (33) | 2 (4) | 18 (33) | 13 (24) |

| Gonorrhoea | 56 | 18 (32) | 2 (4) | 18 (32) | 17 (30) |

| HIV | 56 | 28 (50) | 4 (7) | 28 (50) | 28 (50) |

| Syphilis | 56 | 26 (46) | 5 (9) | 26 (46) | 25 (45) |

| Services on site and at affiliatesE | |||||

| Chlamydia | 55 | 55 (100) | 54 (98) | 36 (65) | 7 (13) |

| Gonorrhoea | 57 | 55 (96) | 54 (95) | 38 (67) | 8 (14) |

| HIV | 56 | 51 (91) | 46 (82) | 37 (66) | 19 (34) |

| Syphilis | 56 | 53 (95) | 50 (89) | 37 (66) | 16 (29) |

Excludes respondents that did not provide testing services for the sexually transmissible infection (STI) of interest.

Respondents that were unaware of the availability of non-anonymous and/or anonymous PN services offered directly on site and/or at their affiliate.

Excludes respondents that provided PN only through an affiliate.

Excludes respondents that did not have an affiliate.

Excludes respondents that did not provide PN services both on site and through an affiliate.

Partner notification methods

Table 4 presents the proportion of respondents offering PN services by PN method. Counselling was the most common PN method available throughout testing sites and affiliates (80–97%). Phone calls were the second most common PN method (63–67%) and the most common among the four anonymous notification methods. Provider-initiated email and/ or social media-based Internet notification was available at only 9–13% of sites and affiliates.

Table 4.

Number of respondentsA offering partner notification (PN) services on site and/or through an affiliate, by method PDPT, patient-delivered partner therapy; NA, not applicable.

| n | No. (%) of survey respondents | No. (%) of unknownB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-anonymous PN | Anonymous PN | ||||||||

| Counselling | PDPT | Referral cards | Phone calls | Field visits | Mailed letters | Internet | |||

| Chlamydia | 70 | 68 (97) | 17 (24) | 14 (20) | 45 (64) | 24 (34) | 30 (43) | 6 (9) | 14 (20) |

| Gonorrhoea | 72 | 68 (94) | 15 (21) | 14 (19) | 48 (67) | 26 (36) | 31 (43) | 6 (8) | 19 (26) |

| HIV | 70 | 56 (80) | NA | 8 (11) | 44 (63) | 36 (51) | 32 (46) | 9 (13) | 30 (43) |

| Syphilis | 70 | 61 (87) | NA | 11 (16) | 46 (66) | 33 (47) | 30 (43) | 9 (13) | 26 (37) |

Excludes respondents that did not provide testing services for the sexually transmissible infection (STI) of interest.

Respondents that were unaware of the availability of at least one of the seven PN services offered directly on site and/or at their affiliate.

The most common form of non-anonymous PN service offered directly on site was counselling for patient referral (78–97%) (Table 5). This method was less frequently available among affiliates (2–9%). PDPT availability at affiliates was also low (2%), whereas 24% and 21% of testing sites offered it on site for chlamydia and gonorrhoea infection, respectively. One site offered HIV-positive patients the option of having a staff member present at the time they notified their partner(s).

Table 5.

Number of respondentsA offering partner notification (PN) services on site and/or through an affiliate, by location and PN method NA, not applicable

| n | No. (%) of survey respondents | No. (%) of UnknownB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-anonymous PN | Anonymous PN | ||||||||

| Counselling | PDPT | Referral cards | Phone calls | Field visits | Mailed letters | Internet | |||

| On-site servicesC | |||||||||

| Chlamydia | 70 | 68 (97) | 17 (24) | 14 (20) | 35 (50) | 14 (20) | 21 (30)F | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Gonorrhoea | 72 | 68 (94) | 15 (21) | 14 (19) | 38 (53) | 16 (23) | 22 (31) | 2 (3) | 0 |

| HIV | 69 | 54 (78) | NA | 8 (12) | 26 (38) | 16 (23)G | 18 (26) | 4 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Syphilis | 69 | 59 (86) | NA | 10 (14) | 29 (42) | 15 (22) | 18 (26) | 3 (4) | 0 |

| Services at affiliatesD | |||||||||

| Chlamydia | 54 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 17 (31) | 15 (28) | 14 (26) | 5 (9) | 13 (24) |

| Gonorrhoea | 56 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 17 (30) | 15 (27) | 14 (25) | 5 (9)H | 17 (31)H |

| HIV | 56 | 4 (7) | NA | 0 | 25 (45) | 26 (46) | 20 (36) | 7 (13) | 28 (50) |

| Syphilis | 56 | 5 (9) | NA | 1 (2) | 24 (43) | 23 (41) | 18 (32) | 8 (14) | 25 (45) |

| Services on site and at affiliatesE | |||||||||

| Chlamydia | 55 | 54 (98) | 13 (24) | 12 (22) | 35 (64) | 21 (38) | 24 (44) | 5 (9) | 14 (25) |

| Gonorrhoea | 57 | 54 (95) | 11 (19) | 12 (21) | 37 (65) | 22 (39) | 25 (44) | 5 (9) | 19 (33) |

| HIV | 56 | 46 (82) | NA | 6 (11) | 34 (61) | 30 (54) | 27 (48) | 7 (13) | 29 (52) |

| Syphilis | 56 | 50 (89) | NA | 9 (16) | 36 (64) | 28 (50) | 25 (45) | 8 (14) | 26 (46) |

Excludes respondents that did not provide testing services for the sexually transmissible infection (STI) of interest.

Respondents that were unaware of the availability of at least one of the seven PN services offered directly on site and/or at their affiliate.

Excludes respondents that provided PN only through an affiliate.

Excludes respondents that did not have an affiliate.

Excludes respondents that did not provide PN services both on site and through an affiliate.

n = 69.

n = 71.

n = 55.

Phone calls were the most frequently reported anonymous PN method available on site (38–53%), followed by mailed letters (26–31%) and field visits (20–23%). The availability of phone call services was also similar among affiliates (30–45%), as was the availability of field visits (27–46%) and mailed letters (25–36%). In contrast, Internet notification was the least offered anonymous notification strategy available on site (3–6%) and at affiliates (9–14%).

Patient-initiated Internet-based PN

Eighteen per cent (13 of 72) of surveyed sites had ever heard of inSPOT. Thirty-one per cent (4 of 13) of such sites regularly referred their patients to inSPOT for patient-initiated Interent-based PN. Awareness of ‘So They Can Know’ was at 3% (2 of 72) of surveyed sites. Ninety per cent (65 of 72) of sites either planned or expressed willingness to refer patients to ‘So They Can Know’ following its release in September 2012 (this survey was administered before the website officially launched).

Discussion

We found that most surveyed testing sites currently offered PN services to patients diagnosed with chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV or syphilis. Although not comprising a representative sample, our findings are comparable to those of a 1995 survey of local health departments, which found that the proportion of health departments offering provider referral to chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis patients was 53%, 67%, and 92%, respectively.9 Golden et al. demonstrated that the proportion of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV and syphilis cases receiving PN services was 25%, 35%, 93%, and 95%, respectively, at health department STI clinics in high prevalence areas in 1998.7

Although most surveyed sites offered PN services, our results indicated that the availability of PN varied by PN method and location of the provision of services. Non-anonymous PN services were available on site throughout most surveyed sites, with patient counselling being the most common method. The low-cost nature of non-anonymous notification may explain its widespread availability. Provider-based anonymous PN, in contrast, reduces commonly reported barriers to non-anonymous PN, such as fear, guilt or discomfort.10–12 It has also been shown to result in higher proportions of notified/treated partners when compared with non-anonymous PN.13 We found that affiliates offered mostly anonymous PN services. However, anonymous PN was offered directly on site at approximately half of surveyed sites, suggesting a reliance on health departments for the provision of anonymous PN services. Anonymous PN is substantially more time- and resource-intensive than non-anonymous PN,13,14 which may account for the more limited availability of this service throughout testing sites.

The low availability of anonymous PN relative to non-anonymous PN throughout surveyed sites highlights the need for methods that provide an appropriate balance between offering the option to notify partners anonymously and maintaining low costs and ease of use. Increasing access to and use of electronic notification methods, the least available method according to our findings, may provide this balance. In patient-initiated Internet-based PN, patients use websites that generate and send anonymous emails, e-cards and text messages to partners at no cost. Several studies have shown this method was acceptable to patients in terms of performing notification, as well as receiving it.15–18 Most sites surveyed in this study expressed willingness to refer their patients to one such website as part of their notification services. Given its acceptability among both patients and providers, patient-initiated Internet-based PN may serve as a potential alternative to provider-based anonymous PN to increase the overall availability of anonymous PN options for patients. Further evaluation research, however, is necessary to assess the effectiveness of this method.

We also found that most surveyed testing sites reported having an affiliate for PN, yet a considerable number were unaware of the specific PN services offered at their affiliate. All survey respondents were knowledgeable testing site staff who were involved in either the management or provision of HIV/STI services, including PN. Increased staff awareness about PN services available at affiliates may be necessary to ensure all STI patients receive needed PN services.

Our study has several strengths. Surveyed sites came from various HIV/STI testing settings, such as family planning clinics, community health centres and health departments. Some studies suggest that most HIV/STI diagnoses can occur in outpatient settings, such as the ones represented in our sample.19 We also included sites in geographically varied locations with low STI incidence rates. One study found that less than two-fifths of diagnoses occur in areas with high HIV/ STI incidence rates.3 The diversity of HIV/STI testing settings, geographical areas and local STI incidence rates represented in our sample broadens the generalisability of our findings. We also collected data from individual sites, allowing for clearer depictions of PN practices at local levels.

The following study limitations should be considered. First, despite a high cooperation rate, the sample size and overall response rate were low. Our sampling list may have had out-of-date testing site contact information, possibly resulting in the high rates of failed call attempts. Thus, our findings may have been subject to a sample bias. Second, respondents were asked which PN services were available either on site or at an affiliate, rather than the number of patients that ultimately receive PN services at these locations. Finally, a significant proportion of respondents with an affiliate could not provide information regarding the specific PN services available at their affiliate. This may have resulted in underestimates of overall PN service availability throughout surveyed testing sites.

Despite these limitations, this study provides a preliminary understanding of current PN practices in the US. Most surveyed sites provide some form of PN service to patients with chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV or syphilis infection, either directly on site, through an affiliate or both. However, a considerable proportion of the surveyed sites do not offer anonymous services on site, which, given their potential to reduce barriers to successful PN, may represent a better option for some patients. Future research should be directed towards assessing the current proportion of patients that are offered and ultimately receive various types of PN services at testing sites throughout the US. A rigorous assessment of novel, particularly low-cost anonymous methods may also be warranted to increase the availability of anonymous services for patients across all testing venues while minimising resource use by service providers.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHSOM) Dean’s Fund for Summer Research, the JHSOM Excellence in Medical Student Research Award, award number U54EB007958 from the HIV Prevention Trials Network, and award number U01–068613 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Kissinger PJ, Niccolai LM, Magnus M, Farley TA, Maher JE, Richardson-Alston G, Dorst D, Myers L, Peterman TA. Partner notification for HIV and syphilis: effects on sexual behaviors and relationship stability. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:75–82. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parran T. Shadow on the land: syphilis. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock; 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathews C, Coetzee N, Zwarenstein M, Lombard C, Guttmacher S, Oxman A, Schmid G. A systematic review of strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:285–300. doi: 10.1258/0956462021925081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schillinger JA, Kissinger P, Calvet H, Whittington WL, Ransom RL, Sternberg MR, Berman SM, Kent CK, Martin DH, Oh MK, Handsfield HH, Bolan G, Markowitz LE, Fortenberry JD. Patient-delivered partner treatment with azithromycin to prevent repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women: a randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:49–56. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerani RP, Fleming M, Golden MR. Acceptability and intention to seek medical care after hypothetical receipt of patient-delivered partner therapy or electronic partner notification postcards among men who have sex with men: the partner’s perspective. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:179–85. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31827adc06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legal status of Expedited Partner Therapy (EPT) Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/default.htm [verified 1 April 2014]

- 7.Golden MR, Hogben M, Handsfield HH, St Lawrence JS, Potterat JJ, Holmes KK. Partner notification for HIV and STD in the United States: low coverage for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, and HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:490–6. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Prevention Information Network. [Accessed April 1, 2014];Databases. Available at: http://www.cdcnpin.org/scripts/about/database.asp.

- 9.Landry DJ, Forrest JD. Public health departments providing sexually transmitted disease services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28:261–6. doi: 10.2307/2136055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chacko MR, Smith PB, Kozinetz CA. Understanding partner notification (Patient self-referral method) by young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2000;13:27–32. doi: 10.1016/S1083-3188(00)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal SL, Baker JG, Biro FM, Stanberry LR. Secondary prevention of STD transmission during adolescence: partner notification. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1995;8:183–7. doi: 10.1016/S0932-8610(19)80140-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorbach PM, Aral SO, Celum C, Stoner BP, Whittington WL, Galea J, Coronado N, Connor S, Holmes KK. To notify or not to notify: STD patients’ perspectives of partner notification in Seattle. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:193–200. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200004000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh MK, Boker JR, Genuardi FJ, Cloud GA, Reynolds J, Hodgens JB. Sexual contact tracing outcome in adolescent chlamydial and gonococcal cervicitis cases. J Adolesc Health. 1996;18:4–9. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortenberry JD, Brizendine EJ, Katz BP, Orr DP. The role of self-efficacy and relationship quality in partner notification by adolescents with sexually transmitted infections. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1133–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.11.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mimiaga MJ, Fair AD, Tetu AM, Novak DS, VanDerwarker R, Bertrand T, Adelson S, Mayer KH. Acceptability of an internet-based partner notification system for sexually transmitted infection exposure among men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1009–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilardi JE, Fairley CK, Hopkins CA, Hocking JS, Temple-Smith MJ, Bowden FJ, Russell DB, Pitts M, Tomnay JE, Parker RM, Pavlin NL, Chen MY. Experiences and outcomes of partner notification among men and women recently diagnosed with chlamydia and their views on innovative resources aimed at improving notification rates. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:253–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d012e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladd J, Gaydos A. Acceptability of innovative methods of anonymous STI partner notification among American adolescents. Analysis presented at the 2012 National STD Prevention Conference; March 2012; Minneapolis, MN: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mimiaga MJ, Tetu AM, Gortmaker S, Koenen KC, Fair AD, Novak DS, Vanderwarker R, Bertrand T, Adelson S, Mayer KH. HIV and STD status among MSM and attitudes about Internet partner notification for STD exposure. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:111–6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181573d84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorell CG, Sutton MY, Oster AM, Hardnett F, Thomoas PE, Gaul ZJ, Mena LA, Heffelfinger JD. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in health care settings among young African American men who have sex with men: implications for the HIV epidemic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:657–64. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]