Abstract

Oxidants or nanoparticles have recently been identified as constituents of aerosols released from various styles of electronic cigarettes (E-cigs). Cells in the lung may be directly exposed to these constituents and harbor reactive properties capable of incurring acute cell injury. Our results show mitochondria are sensitive to both E-cig aerosols and aerosol containing copper nanoparticles when exposed to human lung fibroblasts (HFL-1) using an Air-Liquid Interface culture system, evident by elevated levels of mitochondrial ROS (mtROS). Increased mtROS after aerosol exposure is associated with reduced stability of an electron transport chain (ETC) complex IV subunit and nuclear DNA fragmentation. Increased levels of IL-8 and IL-6 in HFL-1 conditioned media were also observed. These findings reveal both mitochondrial, genotoxic, and inflammatory stresses are features of direct cell exposure to E-cig aerosols which are ensued by inflammatory duress, raising a concern on deleterious effect of vaping.

Keywords: Electronic cigarettes, mitochondria, reactive oxygen species, metals, nanoparticles, inflammation

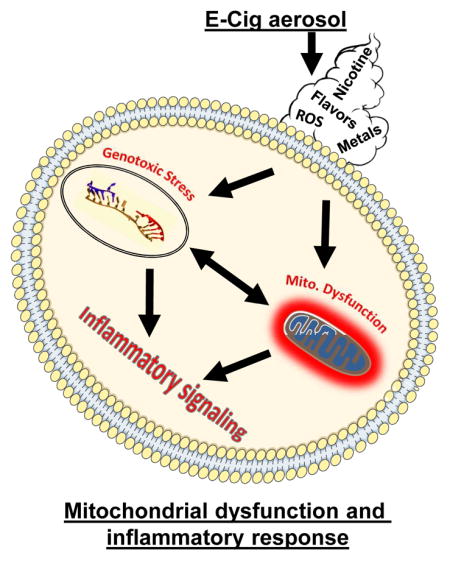

Graphical Abstract

Oxidants and possibly reactive properties of metal particles in E-Cig aerosols imparts mitochondrial oxidative stress and DNA damage. These biological effects accompany inflammatory response which may raise concern regarding long term E-Cig use. Mitochondria may be particularly sensitive to reactive properties of E-Cig aerosols in addition to the potential them to induce genotoxic stress by generating increased ROS.

1. Introduction

Though recent studies suggest that there is reduced potential for toxicity from Electronic cigarettes (E-cigs) aerosols compared to tobacco smoke (1,2), the biological effects of E-cig aerosols exposed directly to lung tissues and cells are not well understood. We and others have confirmed there are also significantly high levels of oxidant reactivity and reactive oxygen species associated with aerosols from E-cigs (3–6). To determine E-cig effects on aspects of cellular toxicity involving mitochondrial metabolism, we utilized an air-liquid interface (ALI) system to better mimic real-life exposure conditions of cells to aerosols. The ALI provides the ability to glean biological effects from the interaction of cells or tissues with the physical and chemical properties of the E-cig liquids in their aerosolized state.

We assessed biological effects of direct E-cig aerosol exposure at the ALI by measuring mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) alterations and any changes to the stability of labile electron transport chain (ETC) complex proteins. Additionally, heavy metal particles found in E-cig aerosols are also a potential mediator of cellular oxidative stress (7). Since we find relatively high levels of copper in the brand of E-cig (4), we monitored the effect E-cig aerosol on mtROS following exposure of human lung fibroblasts (HFL-1) to two forms of copper nanoparticles (oxidized and metallic). The effect of E-cig aerosols on DNA damage of HFL-1 was also assessed using the COMET method to determine the extent of DNA fragmentation relative to the time duration of the exposure sessions and if these changes correlated with an IL-6 and IL-8 cytokine response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scientific Rigor

We used a rigorous/robust and unbiased approach throughout the experimental plans and during analyzing the results so as to ensure that our data are reproducible along with by full, detailed reporting of both methods and raw/analyzed data.

2.2. Cell Culture

HFL-1 human primary lung fibroblasts (alveolar, Caucasian, 16 wk. fetal male) at PD 25 – 35 (11) were cultured at 37°C in DMEM (supplemented with 10% FBS, 1X MEM non-essential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 ug/ml streptomycin Penn/Strep). Before E-cig exposures, cells were cultured to 85–90% confluence under 3.0% O2 in 6-well transwells with 1 micron pores or in T-75 culture flasks (Comet assay only).

2.3. Air Liquid Interface exposure

All ALI exposures carried out under an approved chemical flow hood. Ambient air temperature was maintained at 37°C in an air incubator located inside flow hood which housed ALI exposure vessels during experiments.

HFL-1 cultures for ROS measurements, immunoblotting, and conditioned media experiments were placed into the air-liquid interface (ALI) exposure chamber. All E-cig exposures were carried out with Lorillard Blu Classic Tobacco E-cig with16 mg nicotine (Greensboro, NC). E-cig puffs were regulated with 4 second puffs every 30 seconds for various sessions (5 minute, 10 minute, 15, minute, or 20 minute) using a timer system programed through BASIC that controls a peripheral power supply operating the lab pump (FMI, Syosset, NY). Lab pump was operated at 60% flow rate which is minimally sufficient to activate the E-cig and deliver aerosols through laboratory tubing into the ALI chamber.

For DNA fragmentation assay, HFL-1 cells were cultured in T-75 flasks and fitted on a modified test-tube rotator rod. Prior to each puff into the flask using lab tubing, its position was rotated 45° to 90° so the media collected to the side. Air or E-cig aerosols were puffed over the cells from the opening of the flask.

2.4. Mitochondria superoxide staining

Live HFL-1 cells were stained 45 minutes following ALI chamber exposures or 24 hour exposure to 1 mg/mL metal nanoparticles and metal oxides (TiO2, CuO, Cu40, C60) in culture dishes. Concentration of 2.5 μM Mitosox was used for mitochondrial staining according to manufacturer instructions (Life Technologies). Cells were counterstained with NucBlu (Molecular Probes) for imaging. Live cell images (20X) were captured on Nikon Eclipse Ni fluorescent microscope. HFL-1 Mitosox fluorescence was quantitated on a BD accuri Flow cytometer using FL2 laser and data analyzed on Flow Jo 10 software.

2.5. Mitochondria membrane potential staining

Live HFL-1 cells stained with TMRE 24 hours after exposure to metal nanoparticles (TiO2, CuO, Cu40, C60) at 1uM for 15 minutes according to manufactures instructions (Life Technologies). TRME fluorescence was quantitated on BD LSR II flow cytometer with blue C 585 excitation laser and data analyzed on Flow Jo 10.

2.6. Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were collected from HFL-1 exposed to Air or E-cig aerosols either from the ALI chamber or ALI carried out in T-75 flasks. For ALI chamber, HFL-1 cells were collected from transwells18 hours after exposures using 0.25% trypsin. Lysis was performed in RIPA buffer by vortex and multiple freeze thawing. Protein (20 mg) loaded onto a 10% PAGE-Gel and transferred to nitrocellulous following electrophoresis. Detection of ETC proteins carried out with 1:2000 dilution of human OxPhos antibody cocktail (Abcam, UK). Lysates prepared for OxPhos antibody detection by immunoblot were denatured and reduced using 1% SDS and 200 mM 2-mercaptoethanol respectively and never heat denatured. For HFL-1 lysates from T-75 flask, cells were collected 1 hour following ALI exposures. Proteins were immunoblotted for detection of human Nqo1 at 1:1000 dilution (Santa Cruz, CA).

2.7. DNA fragmentation assay

DNA fragmentation in HFL-1 cells exposed to E-cig aerosols were carried using ALI carried out in T-75 flasks. Following exposures, cells were collected and processed for comets according to the Kit manufacturer’s instructions (Trevigen, MD). Fluorescent comet images of cells were collected at 20X and DNA fragmentation was quantitated as Olive Tail Moment calculated by Image J comet plug in.

2.8. ELISA

Following ALI chamber exposures, transwells were placed into 6 well plates with 3 mL fresh growth media. Conditioned media was collected 18 hours later and IL-8 and IL-6 cytokine secretion determined using the dual antibody ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, MA).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical analysis of significance was calculated using 2-Tailed Student’s t-Test. P < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. E-cig aerosols elevate mitochondrial ROS in cultured lung human fibroblasts

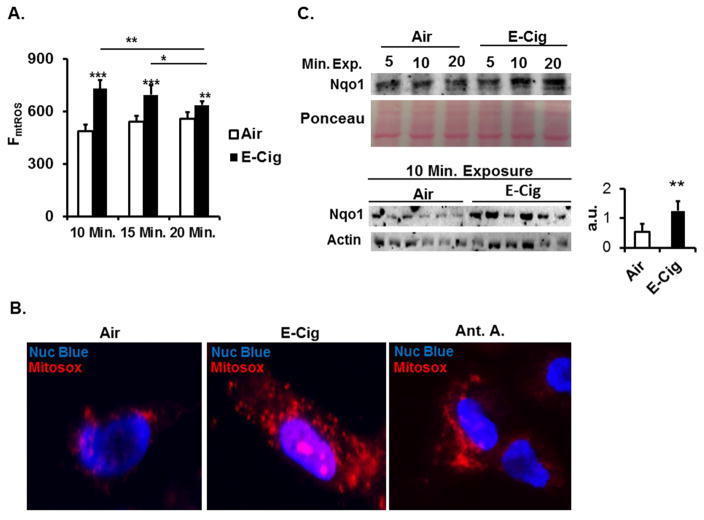

Since changes in mtROS levels can be associated with a toxic response to environmental insult (8), we sought to test the possibility that direct exposure of human lung cells to E-cig aerosols affects mitochondrial redox dynamics. HFL-1 cells exposed to E-cig aerosols at the ALI results in acute increased production of mtROS compared to steady state levels of mtROS in air exposed control cells (Fig. 1A). Increasing exposure duration did not significantly increase mtROS levels in aerosol exposed cells compared to air control groups. Rather, there is a slight yet significant reduction in the amount of mtROS present after 20 minute duration aerosol exposure compared to 10 minute or 15 minutes (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Mitochondrial ROS elevated by E-cig aerosols.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of HFL-1 cells stained with Mitosox following Air or E-cig exposure for indicated time periods in ALI chamber. Each measurement represents n = 6. Data expressed as mean ± SD (error bars). Significance comparison between Air control and E-cig denoted by asterisk. Comparison between E-cig aerosol exposure time points denoted by asterisk with crossbar. (B) Representative fluorescent microscopy live-cell images of HFL-1 cells exposed in ALI chamber to 10 minute session of ambient Air or E-cig aerosols. Regions of elevated mitochondrial ROS are viewed in red following Mitosox staining. Antimycin A treated HFL-1 cells in culture shown as Mitosox stained positive control. Nucleus counterstaining by Nuc Blue live-cell reagent. Original magnification: 20x (C) Top: Immunoblot for detection of Nqo1 activated by ARE response element. Image represents Air control versus E-Cig aerosol ALI exposure at indicated sessions. Lysates collected 15 minutes after exposures. Ponceau stain of total protein shown for even loading. Prominent ponceau band (43 kD) presumed to be Actin. Bottom: Immunoblot detecting Nqo1 following 10 minute ALI exposure. Lysates collected 18 hours after exposures. *P ≤ 0.05,** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001, significant compared to Air control group.

Live mitochondria with elevated ROS are visualized with fluorescent microscopy after Air or E-cig aerosol exposures and Mitosox staining. E-cig aerosol exposed HFL-1 cells reflected similar staining effects for presence of mtROS to HFL-1 treated with mitochondrial complex III inhibitor Antimycin A (Fig. 1B). Next, we determined if E-cig aerosols play a role in mediating activation of antioxidant response element (ARE)-inducing genes since longer exposure sessions appeared to slightly attenuate mtROS production. Either Air or E-cig aerosol exposure was carried out for 5 minute, 10 minute, or 20 minute exposure session with totally cellular proteins collected shortly after exposures. The level of ARE inducible Nqo1 expression increased for the 10 minute and 20 minute exposure sessions (Fig. 1C). Similarly, exposure of HFL-1 for a 10 minute session with E-cig aerosols resulted in increased average Nqo1 levels when cellular proteins were collected 18 hours following exposures (Fig 1C). Thus, E-cig aerosols are sufficient to elevate mtROS and trigger antioxidant response element (ARE) responsive genes.

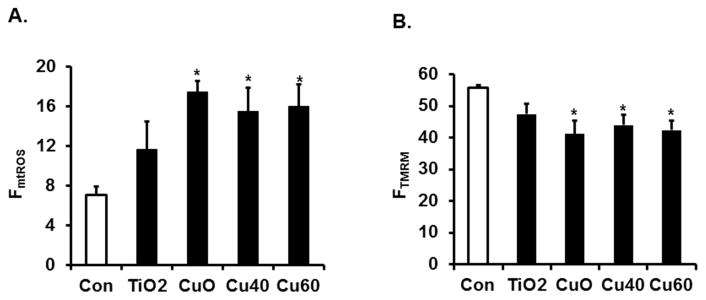

3.2. Metal particles identified in E-cig aerosol induce mtROS

We and others have previously detected copper or titanium in E-cig aerosols (4, 7). To determine if these metals alone could influence levels of mROS, HFL-1 cells in culture were treated with TiO2, CuO (30 nm), or metallic Cu nanoparticles 40, and 60 (40nm, 60nm). After 24 hours, there was a significant increase in the level of mtROS in cells treated with the copper metal nanoparticles (Fig. 2A). The increase in mtROS occurred concurrently with reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 2B). For TiO2, there was an increase average level of mtROS and decrease average level of membrane potential (Fig. 2A and 2B) though neither change was significant (p > 0.05). These data suggest a possible mediator of mtROS generation by E-cig aerosols might depend on the presence of metal particles such as copper released from the E-cig.

Fig. 2. Metal nanoparticles associated with E-cig aerosols induce mitochondrial dysfunction.

Flow cytometry analysis of Mitosox (A) or TMRE (B) stained HFL-1 cells treated prior for 24 Hrs with metals reported in E-cig aerosols: Titanium Dioxide (TiO2), copper oxide (CuO), copper oxides; (Cu40 and Cu60). Data expressed as percent positive fluorescent mean ± SD (error bars). *P ≤ 0.05,** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001, significant compared to Air control group.

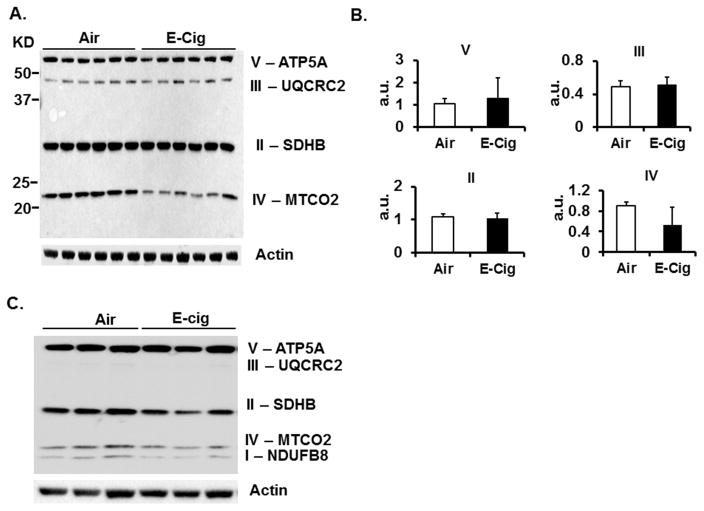

3.3. Mitochondrial complex IV stability is sensitive to E-cig aerosols

Since mtROS levels were acutely affected by exposure to the aerosols, single ETC protein subunits representing each of the IV complexes were measured for stability. Compared to ALI Air exposed HFL-1 cells, E-cig aerosol exposed cells exhibited complex IV sensitivity as observed by decreased levels of COX II (MTCO2) subunit in cell lysates collected 18 hours after aerosol exposure (Fig. 3A and 3B). A reduced level of complex I NDUFB8 subunit in addition to reduced COXII was observed in cell lysates harvested 90 minutes after exposure (Fig. 3C) Therefore, the impact of E-cig aerosol exposure on mitochondrial dynamics includes alterations to respiratory components.

Fig. 3. Sensitivity of select electron transport chain complex subunits to E-cig aerosols.

(A) Immunoblot comparing relative levels of labile ETC complex subunits in HFL-1 total cell lysates collected 18 hours after cells exposed to Air or E-Cig aerosol in a 10 minute session. Image representative of two separate experiments shown. (B) Densitometry analysis of bands in (A) for each ETC subunit resolved on blot. Relative intensity of subunit bands are expressed as mean ± SD (error bars) for each exposure group. *P ≤ 0.05, significant compared to Air control group. (C) Immunoblot of separate experiment carried out similarly as in (A) except with total cell lysates collected 90 minutes after cells exposure.

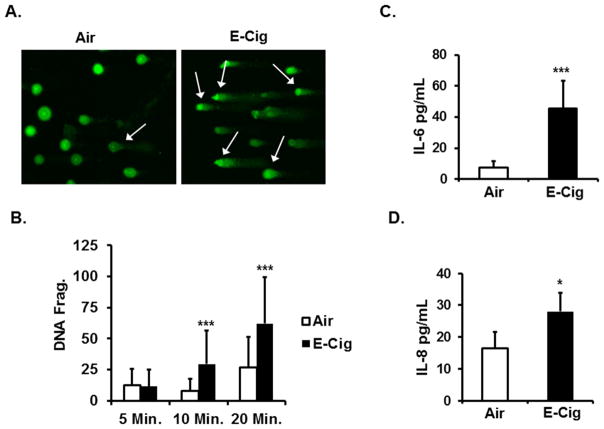

3.4. E-cig aerosols promote whole cell DNA fragmentation

We measured the extent of DNA fragmentation in HFL-1 cells exposed to E-cig aerosols. The alkaline comet assay allowed visualization and later quantification of the extent of DNA fragmentation after ALI exposures (Fig. 4A). Although a 5 minute aerosol exposure did not produce any difference in DNA fragmentation, longer exposure sessions (10 minute and 15 minute) resulted in significant increases in DNA fragmentation compared to Air control groups (Fig. 3B). However, as the exposure duration increased, the likelihood for DNA damage increased in the Air control group as well. The percent increase in DNA fragmentation in E-cig aerosol to Air exposed control group for the 10 minute session is higher (74% increase) compared to the 15 minute session (57% increase) suggesting longer aerosol exposure did not further enhance DNA fragmentation even though increased DNA fragmentation is an outcome of E-cig aerosol exposure.

Fig. 4. Lung cell susceptibility to DNA damage by exposure to E-cig aerosols and release of pro-inflammatory chemotactic cytokines.

(A) Representative fluorescent microscopy images of Air control or E-Cig aerosol exposed HFL-1 cells analyzed for DNA fragmentation by Comet. (Cells exhibiting DNA fragmentation indicated by arrows), Original magnification: 20x. (B) Air or E-Cig aerosol exposed cells quantitated for DNA fragmentation by Comet at indicated exposure sessions times. Level of DNA fragmentation calculated as Olive Tail Moment and data expressed as mean ± SD (error bars).*** P ≤ 0.001, significant compared to Air control group. (C) Amount of IL-6 detected conditioned media from HFL-1 cells exposed to Air or E-Cig aerosols in ALI chamber for a 10 minute session. (D) Amount of IL-8 in conditioned media after same exposure conditions as described in (A). Cytokine levels for both (C) and (D) measured by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (error bars), (n=3 per measurement). * P ≤ 0.05, *** P ≤ 0.001, significant compared to Air control group.

3.5. E-cig aerosol induced secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 from HFL-1

We followed up on our DNA fragmentation and altered mtROS results by quantitating post E-cig aerosol ALI exposure levels of HFL-1 pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 in conditioned media. A 10 minute aerosol exposure session resulted in increased IL-6 secretion (45.70 pg/mL) after 18 hours post E-cig exposure compared to IL-6 levels (7.34 pg/mL) from Air control group (Fig. 4C). IL-8 levels (28.02 pg/mL) compared to Air group (16.42 pg/mL) was also increased (Fig. 4D). From this data, we conclude ALI E-cig aerosol exposure elicits inflammatory signaling which reflects an inflammatory distress response and indicates E-cig aerosols are capable of mediating biological effects associated with increased mtROS and genotoxic stress.

4. Discussion

We used HFL-1 to test the hypothesis as these cells have been shown to undergo cellular senescence via mitochondrial dysfunction by cigarette smoke extract (9). Following HFL-1 aerosol exposure using the ALI, we observed an increase in mtROS. The HFL-1 cells appear to have the ability to limit further mtROS production from longer exposures. The 20 minute exposure session resulted in significant increase in mtROS compared to Air control, however, levels were somewhat reduced compared to a 10 minute ALI aerosol exposure. This suggests that it is possible equilibrium between mtROS production and antioxidant activity is achieved. This would be consistent with our results showing time dependent induction of NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (Nqo1) in cells harvested both shortly after E-cig aerosol exposures and additionally following 18 hour post exposure incubation. The elevated level of mtROS we observe may thus, reflect a signaling response that could mediate antioxidant regulation. E-cig aerosol upregulation of the antioxidant response element (ARE) protein Nqo1, suggests activation of the Nrf2 pathway. E-cigs are capable of producing carbonyls to various amounts (some considered very high) which is partly due to voltage, but may be due to nicotine solvent, flavors, or device design (10,11). The device we used for our ALI exposures functions at 3.7 V which is sufficient to produce carbonyl compounds (12). Increased Nqo1 levels indicate electrophilic reactivity may also be present in E-cig aerosols as Nqo1 regulation by Nrf2 is highly sensitive to electrophiles. This finding is not completely unexpected considering aldehyde compounds can harbor electrophilic activity and have been detected in E-cig aerosols (13,14). However, it is unknown whether E-cig aldehyde reactivity in aerosols is contributing to enhanced Nqo1 levels we observe using a device with disposable cartomizer.

Our results show that mitochondria respond acutely to direct E-cig aerosol exposure by increasing mtROS to higher relative levels compared to air exposed cells. Complexes I and III are known to be the major source of superoxide (O2−) mtROS. Acutely inhibiting bc1 complex III subunit with antimycin A will block electron transport to cytochrome c leading to enhanced O2− generation which is the presumed target of the Mitosox indicator dye. Though we did not assay for changes in ETC complex activity, we find significant reduction in the stability of complex IV cytochrome C oxidase subunit II (mtCOII). It is proposed this may result in inefficient transfer of electrons and promote “electron leak” leading to formation of mtROS rather than efficient reduction of O2 to water.

Mitosox detection of increased mtROS levels occurred approximately 1 hour after E-cig aerosol exposure. However, the loss of stability in mtCOII subunit was apparent 18 hours after E-cig aerosol exposure when lysates were collected. This could indicate the toxicity of the E-cig persisted in stressing the cell short of one day after exposure. Though, it is unclear if disruption in mtCOII stability occurred relatively early following aerosol exposure since one hour following exposure, cells were either mounted for Mitosox fluorescent microscopy or collected for FACS analysis.

Both DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction are involved in mediating inflammation signaling. The elevated levels of IL-6 and IL-8 are observed from conditioned media 18 hours after E-cig aerosol exposure which correlates with the increased DNA fragmentation and altered mitochondrial dynamics observed. The increased duration of exposure to E-cig aerosol between 10 minute and 20 minute durations did not further increase DNA fragmentation relative to Air group. We conclude higher overall levels of DNA fragmentation at longer exposure duration for both Air and E-cig aerosols likely reflects, mechanical stressors, Air flow, and media flow over cells.

Copper nanoparticles have the capacity to mediate oxidative stress and genotoxicity. The relatively high levels of copper we detect in the aerosols of the particular E-cig device we tested (4) is one of a number of metals identified in the aerosols of a similar style of E-cig compared to levels of metal particles in tobacco smoke (7). In comparison to other airborne pollutants, copper oxide which we tested, is capable of generating high levels of oxidative stress in lung cells. It cannot be concluded from this study that the mtROS produced by E-cig aerosols, contributes to the DNA fragmentation we observe, or if the copper released from this particular device is also involved in mediating cell stress. HFL-1 cells treated separately with a variety of copper nanoparticles exhibited significant increases in mtROS while concurrently cause a reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential which is consistent with reported effect of copper toxicity in cultured astrocytes and neurons (15). We also treated HFL-1 with Titanium dioxide (TiO2) particles which have been shown to induce cellular cytotoxicity and induce DNA damage in lung cells, but did not elicit significant increases in mtROS or reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential. We do not know if our particular device releases titanium or not. Elevated mitochondrial ROS may not be overwhelmingly stressful except when formed in the presence of transition metals such as copper which promote formation of reactive nitrogen species in various cell types (15). We further found that E-cig derived copper particles disrupted mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial mass, ATP levels, and mtROS in primary human airway epithelial cells implicating mitochondrial dysfunction by E-cig aerosol (data not shown). Oxidants and possibly reactive properties of metal particles in E-cig aerosols impart mitochondrial oxidative stress and DNA damage. These biological effects accompany inflammatory response which may raise concern regarding long term E-cig use. Mitochondria may be particularly sensitive to reactive properties of E-cig aerosols in addition to the potential them to induce genotoxic stress by generating increased ROS. The reactive properties of E-cig aerosols on cells or tissue however, require further examination to gather better conception of E-cig usage versus risk.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Mitochondria are sensitive to both E-cig aerosols and metal nanoparticles.

Increased mtROS by E-cig aerosol is associated with disrupted mitochondrial energy

E-cig causes nuclear DNA fragmentation.

E-Cig aerosols induce pro-inflammatory response in human fibroblasts.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the NIH 2R01HL085613 (to I.R.), 3R01HL085613-07S2, and pulmonary training grant T32 HL066988, and NIEHS Environmental Health Science Center grant P30-ES01247.

Footnotes

Author contributions:

CAL and IR: Conceived and designed the experiments; CAL, PG, IKS: Performed the experiments and analyzed the data; CAL and IR: wrote the manuscript.

Conflicting interests: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, Allifranchini E, Ripamonti E, Bocchietto E, Todeschi S, Tsiapras D, Kyrzopoulos S, Voudris V. Comparison of the cytotoxic potential of cigarette smoke and electronic cigarette vapour extract on cultured myocardial cells. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2013;10:5146–5162. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10105146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romagna G, Allifranchini E, Bocchietto E, Todeschi S, Esposito M, Farsalinos KE. Cytotoxicity evaluation of electronic cigarette vapor extract on cultured mammalian fibroblasts (ClearStream-LIFE): comparison with tobacco cigarette smoke extract. Inhalation toxicology. 2013;25:354–361. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2013.793439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goel R, Durand E, Trushin N, Prokopczyk B, Foulds J, Elias RJ, Richie JP., Jr Highly reactive free radicals in electronic cigarette aerosols. Chemical research in toxicology. 2015;28:1675–1677. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerner CA, Sundar IK, Watson RM, Elder A, Jones R, Done D, Kurtzman R, Ossip DJ, Robinson R, McIntosh S, Rahman I. Environmental health hazards of e-cigarettes and their components: Oxidants and copper in e-cigarette aerosols. Environmental pollution. 2015;198:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerner CA, Sundar IK, Yao H, Gerloff J, Ossip DJ, McIntosh S, Robinson R, Rahman I. Vapors produced by electronic cigarettes and e-juices with flavorings induce toxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response in lung epithelial cells and in mouse lung. PloS one. 2015;10:e0116732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sussan TE, Gajghate S, Thimmulappa RK, Ma J, Kim JH, Sudini K, Consolini N, Cormier SA, Lomnicki S, Hasan F, Pekosz A, Biswal S. Exposure to electronic cigarettes impairs pulmonary anti-bacterial and anti-viral defenses in a mouse model. PloS one. 2015;10:e0116861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams M, Villarreal A, Bozhilov K, Lin S, Talbot P. Metal and silicate particles including nanoparticles are present in electronic cigarette cartomizer fluid and aerosol. PloS one. 2013;8:e57987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer JN, Leung MC, Rooney JP, Sendoel A, Hengartner MO, Kisby GE, Bess AS. Mitochondria as a target of environmental toxicants. Toxicological sciences. 2013;134:1–17. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad T, Sundar IK, Lerner CA, Gerloff J, Tormos AM, Yao H, Rahman I. Impaired mitophagy leads to cigarette smoke stress-induced cellular senescence: implications for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. FASEB J. 2015;29:2912–29. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-268276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Fik M, Knysak J, Zaciera M, Kurek J, Goniewicz ML. Carbonyl compounds in electronic cigarette vapors: effects of nicotine solvent and battery output voltage. Nicotine & tobacco research. 2015;16:1319–1326. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Prokopowicz A, Kurek J, Zaciera M, Knysak J, Smith D, Goniewicz ML. Cherry-flavoured electronic cigarettes expose users to the inhalation irritant, benzaldehyde. Thorax. 2016;71:376–377. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchiyama S, Ohta K, Inaba Y, Kunugita N. Determination of carbonyl compounds generated from the E-cigarette using coupled silica cartridges impregnated with hydroquinone and 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, followed by high-performance liquid chromatography. Analytical sciences. 2013;29:1219–1222. doi: 10.2116/analsci.29.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekki K, Uchiyama S, Ohta K, Inaba Y, Nakagome H, Kunugita N. Carbonyl compounds generated from electronic cigarettes. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2014;11:11192–11200. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111111192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng T. Chemical evaluation of electronic cigarettes. Tob Control. 2014;23(Suppl 2):ii11–17. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy PV, Rao KV, Norenberg MD. The mitochondrial permeability transition, and oxidative and nitrosative stress in the mechanism of copper toxicity in cultured neurons and astrocytes. Laboratory investigation. 2008;88:816–830. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.